Abstract

Severe loss of body height is often a consequence of osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Osteoprotegerin (OPG) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB ligand (RANKL) are cytokines essential for the regulation of bone resorption. The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between the OPG/RANKL system and height loss. A total of 4,435 inhabitants from the municipality of Tromsø, Norway (2,169 men and 2,266 women) were followed for 6 years. Baseline measurements included height, weight, bone mineral density, OPG, RANKL, serum parathyroid hormone and information about lifestyle, prevalent diseases and use of medication. Height was measured again at follow-up, and the loss of height was categorized into 4 groups: ≤1, 1.1–2, 2.1–3, >3 cm. We found increasing height loss with increasing baseline OPG levels in both men and women (P trend = 0.02 and 0.001, respectively), after adjustments for age and other confounders. However, when the women were stratified according to menopausal status and use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT), a significant relationship was present only among postmenopausal women not using HRT (P trend = 0.02). No relations between OPG and height loss were found in post-menopausal HRT-users and premenopausal women (P trend ≥0.39). We conclude that height loss is positively associated with OPG in men and in postmenopausal women not using HRT. No relationship was found between RANKL and height loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Height loss increases with age and is related to aging chances in joints, muscles and bone. While a minor degree of height loss is common and probably not associated with any health problems, severe height loss (at least 2 cm over 3–7 years) is often a consequence of osteoporotic vertebral fractures [1–7].

Osteoprotegerin (OPG) and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB ligand (RANKL) are cytokines essential for the regulation of bone resorption [8, 9]. Osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption is induced when RANKL binds to its receptor RANK on osteoclast precursors promoting osteoclast maturation and activation. This binding may, however, be prevented by OPG, which competitively binds RANKL, whereby osteoclast differentiation, activation and survival are inhibited [10]. The OPG/RANKL system is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, but also an important link between a number of cytokines and hormones including sex steroids, the immune system (TNF-alpha, interleukins, glucocorticoids), parathyroid hormone and bone turnover [11].

Previous studies have shown that women tend to loose more height than men after the age of 50 [12, 13], that height loss is positively related to bone loss of the forearm and lumbar spine in women [14, 15] and that bone loss increases with increasing OPG levels in postmenopausal women not using HRT [16]. Only few studies have examined the effect of OPG or RANKL on fracture risk in humans. The cross-sectional studies have found either decreased [17] or increased [18] OPG levels in postmenopausal women with prevalent fractures. In studies of persons followed longitudinally, one study found no association between OPG and all types of self-reported fractures in postmenopausal women [19], another study found that low RANKL levels were associated with an increased risk of non-traumatic fracture in both men and women [20]. No longitudinal studies have been performed with regard to vertebral fractures specifically.

Because severe height loss may serve as a proxy for vertebral fractures, we assessed the relationship between the OPG/RANKL system and the loss of height in participants of a large population-based prospective study.

Materials and methods

Study population

The Tromsø Study is a population-based, longitudinal study with repeated health surveys of inhabitants in the municipality of Tromsø, Norway. It focuses on chronic and lifestyle related conditions such as atherosclerosis and osteoporosis. The regional ethical committee approved the survey, and the participants gave written informed consent.

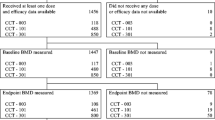

The subjects included in our analyses constitute a group of men and women who were subject to ultrasonography of the carotid artery twice, in the 4th and 5th surveys of Tromsø Study in 1994 and 2001, respectively. At the fourth survey in 1994–1995, all inhabitants aged 55–74 years, and 5–10% random samples of the other 5-year birth cohorts older than 24 years of age were invited to participate in a two-part survey. The first part included standardized measurements of height, body weight, blood pressure and non-fasting serum lipids; the second part (4–12 weeks later) included measurements of bone mineral density and carotid ultrasonography. A total of 6,727 subjects (74% of the eligible population) completed the examination.

Seven years later, in 2001, all of these 6,727 subjects who were still living in the municipality (had not died or moved out of Tromsø) were invited to a repeated examination. This was conducted in 4,858 subjects (82% of the eligible and 72% of the original baseline cohort). However, information about OPG, RANKL, bone mineral density or height (in 1994 or 2001) was missing in 372 subjects. The available information concerning menstruation [16] was missing or inconsistent in 51 women, and these women were excluded. Thus, 2,169 men and 2,266 women were included in the present analyses. The persons with follow-up measurements were younger than those we did not follow. Moreover, the prevalence of smoking in the former group was lower, fewer were teetotallers, and they were more physically active and had a lower prevalence of cardiovascular diseases.

Among the 2,266 women included in the study, 248 were classified as premenopausal and 2,018 were classified as postmenopausal. In the latter group, 422 used HRT and 1,596 did not.

Measurements

In 1994–1995, information about smoking and alcohol habits, physical activity, prevalent cardiovascular diseases and (for women) use of HRT and menopausal status was collected from self-administered questionnaires [21]. Height was measured to the nearest centimeter with a wall-mounted ruler, a method that is as precise as a stadiometer [22], and weight was measured to the nearest half-kilogram. For both measurements the subjects were wearing light clothing and no shoes. Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). Anthropometric measurements were performed in the same way in the fifth survey in 2001–2002.

The concentrations of total OPG and RANKL were analyzed in frozen serum aliquots stored at −70°C. OPG was analyzed by an ELISA assay (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) with mouse anti-human OPG as capture antibody. Biotinylated goat anti-human OPG and streptavidin horseradish peroxydase were used for detection. The OPG assay was performed according to the instructions by the manufacturer. The detection limit was 62.5 pg/ml. The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation in our laboratory were 3.2 and 6.8%, respectively. Between-assay variation in OPG was adjusted for by use of an internal standard.

The concentration of RANKL was measured by a new, highly sensitive ELISA assay for free (soluble) RANKL with a detection limit of 0.02 pmol/l (ampli sRANKL human, Biomedica, Vienna, Austria). The analysis was performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation for the RANKL assay were 9.3 and 15.0%, respectively.

Intact serum parathyroid hormone was analysed by sandwich test principle with monoclonal antibodies reactive to epitopes in the amino acids regions 26–32 and 37–42 (reagents from Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), in a Modular E Autoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics). The analytical coefficient of variation was <3%.

All analyses were performed on coded samples without knowledge of status regarding changes in body height by the person performing the assays. All samples were analyzed in duplicate and the mean value is used in this report.

BMD of the distal and ultradistal forearm was assessed as previously described with single X-ray absorptiometry (DTX-100, Osteometer MediTech, Inc., Hawthorne, CA, USA), and all scans were reviewed in order to detect and correct possible artifacts before analysis [23]. A total of 111 subjects had repeated measurements. The median coefficients of variations for two scans performed 1 week apart by two different operators were 0.79 and 0.98% at the distal and ultradistal sites, respectively [24]. BMD was measured in a similar way at follow up in 2001–2002 in 4,116 of the persons who were included at baseline.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the study population are presented as means (SD) for continuous variables or percentages for dichotomous variables. RANKL levels below 0.02 pmol/l (the limit of detection) were set to 0.01 pmol/l, and because the RANKL levels were not normally distributed they are presented as median as well.

The baseline characteristics of the participants (men, and women stratified with respect to postmenopausal status and HRT-use) were compared by use of ANCOVA with adjustments for age.

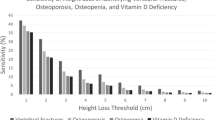

The participants were divided into 4 groups with respect to loss of body height during follow-up: ≤1, 1.1–2, 2.1–3, >3 cm, and baseline OPG levels for these different groups were assessed by use of ANCOVA with adjustments for potential confounders. Trends over the groups were tested using multiple regression analyses.

Multiple regression analyses were also used when height loss as a continuous variable was used rather than height loss groups. Possible differences in the associations between OPG and height loss in the different groups of women were tested by including interaction terms in the model.

Similar analyses were performed for RANKL. The RANKL values were also compared after they had been logarithmically transformed.

A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The data were analyzed using the Windows 15.0 version of SPSS.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the study groups are presented in Table 1.

Age-adjusted comparisons between the groups showed that they differed significantly with respect to all variables presented in the table, except for serum parathyroid hormone levels and RANKL (log transformed). Moreover, the age at menopause did not differ between the postmenopausal women who were users and non-users of HRT.

Table 2 shows that the age adjusted OPG levels increased with increasing height loss in both women and men (P trend ≤0.001 and 0.007, respectively). The relationships were very similar after adjustments for body mass index, smoking habits, physical inactivity, prevalent cardiovascular disease, serum parathyroid hormone and BMD of the distal forearm (Table 2). In the subgroup of 4,116 persons (2,124 women and 1,992 men) with measurements of BMD at follow-up, the results were almost the same after adjustments for change in BMD instead of BMD baseline measurements (results not shown).

When the women were stratified according to menopausal status and use of HRT, a significant relationship was present only among postmenopausal women not using HRT (P trend = 0.02, after multiple adjustments). No relations between OPG and height loss were found in post-menopausal HRT-users or in premenopausal women (P trend ≥0.39). The adjusted association between OPG level and height loss in postmenopausal women not using HRT was statistically significantly different from that in premenopausal women (P = 0.001), but not statistically significantly different from that in postmenopausal women using HRT (P = 0.7).

With height loss as a continuous variable (instead of height loss groups) OPG increased by 0.05 ng (P = 0.002) and 0.02 ng (P = 0.6) per cm height loss in postmenopausal women not using and using HRT, respectively, and decreased by 0.05 ng per cm height loss (P = 0.6) in premenopausal women.

RANKL levels were not related to height loss in men or in any of the groups of women (P trend ≥0.24) (Table 2).

The OPG/RANKL ratio was also not significantly related to height loss (P trend ≥0.24), (results not shown in the table).

BMD of the distal and ultradistal forearm correlated significantly with each other (r = 0.9, P < 0.001) and adjustments for BMD of the ultradistal site gave similar results as those reported for the distal forearm (results not shown).

Discussion

In this population-based study, increasing serum OPG levels were associated with height loss in men and in postmenopausal women not using HRT, whereas no relationship was found in premenopausal women or postmenopausal women taking HRT. RANKL was not related to height loss in any of the groups.

Height loss is associated with age related changes of the posture, decreasing height of the intervertebral discs and lower muscle strength. However, height loss is also strongly related to the development of osteoporosis, and in longitudinal studies of elderly women with repeated measurements of height, a loss of ≥2 centimetres during 3–7 years indicate vertebral fracture [4, 7]. In older women, height loss is also associated with excess BMD decline and an increased risk of all fracture types [25].

The present study is the first to examine the relationship between the OPG/RANKL system and height loss. No longitudinal studies have been performed with regard to vertebral fractures specifically, but in a prospective study of 490 postmenopausal women, no association was found between OPG and all types of self reported fractures [19]. However, in a post-hoc analysis, the women who sustained a hip fracture had higher OPG levels. In another study Schett et al. [20] found that low RANKL levels were associated with an increased risk of non-traumatic fracture in both men and women.

Several cross-sectional studies have examined the relationship between BMD and OPG, finding no association [19, 26–36], a positive [37] and an inverse relationship between the two [18, 38–40]. Only few longitudinal studies are available, and whereas we found that high OPG levels were associated with bone loss in postmenopausal women not using HRT [16], two other (but much smaller) studies found no relationship [34, 41]. RANKL was not related to bone loss in any of these studies.

In the present study we show that the relationship between height loss and OPG was not explained by BMD. One may speculate that although OPG seems to be a marker of BMD loss, it may also be a marker of other structural changes of the vertebrae, such as changes in the micro-architecture of the bone, which we did not measure. Although we cannot exclude that OPG is related to other factors that influences changes in posture (e.g., muscle strength and intervertebral disc height), we believe that this is unlikely.

Experimental data from animals have shown that the deletion of the OPG gene promoted severe osteoporosis in mice, and that in transgenic mice overexpression of OPG from midgestation completely prevented the lesions [42]. Moreover, mice with targeted deletion of the RANKL gene developed osteopetrosis [43] whereas parenteral administration of RANKL led to massive osteoporosis [44]. Modulation of the OPG-RANKL system has a significant impact on BMD and fracture risk also in humans. Denosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANKL that blocks its binding to RANK, and it was recently shown that treatment with Denosumab reduced bone resorption and increased BMD, but most importantly reduced the risk of vertebral, non-vertebral, and hip fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporoses [45]. It has therefore been speculated that the high OPG levels found in some studies of humans with low bone mass may reflect an attempt to counter balance the development of osteoporosis.

The development of osteoporosis is clearly related to estrogen deficit in women, but recent studies have shown that estradiol also seems to play an important role regarding the risk of vertebral and non-vertebral fracture in elderly men [46–48]. In the present study high OPG levels were related to severe height loss in men as well as in postmenopausal women not using HRT.

The present study has some limitations. We suspect that vertebral fractures were common in the groups with the highest height loss, as previous studies have found that a height loss of ≥2 cm, calculated from actual measurements, indicate fracture [4, 7]. However, the study would clearly have been strengthened if we had been able to assess the incidence of vertebral fractures during follow-up and assess whether these fractures were due to osteoporosis [49].

Another limitation is related to the fact that serum concentrations of OPG and RANKL are produced by many tissues and do not fully reflect the local milieu within the bone microenvironment. In addition, most RANKL is cell-bound and not detected in the circulation. Furthermore, 37% of our population has serum RANKL levels below the limit of detection. This percentage is lower than in most previous studies, but the interpretation of the relationship between height loss and RANKL (as well as the OPG/RANKL ratio) is limited due to the relatively high percentage of participants with undetectable RANKL.

There were 248 premenopausal women and 422 postmenopausal women who used HRT included in the analyses, and these low numbers may imply power limitations. For the premenopausal women there was an inverse relationship (decreasing OPG levels with increasing height loss) contrary to what we found for postmenopausal women who did not use HRT, and the association in the two groups of women was statistically significantly different. This significant interaction seems to support the hypothesis that the relationship is influenced by estrogen levels. The relationship in the postmenopausal women who did or did not use HRT was not significantly different, however, and we can not exclude that if the number of postmenopausal women using HRT had been higher, a positive relationship between height loss and OPG would have been found also in this group of women.

A concern is also related to the possibility of bias. Although our study group was large and had a high attendance rate, severely ill or disabled individuals were underrepresented. Moreover, the persons with follow-up measurements were younger and healthier than those we did not follow. However, if such bias should contribute to the findings of a relationship between OPG and height loss in men and postmenopausal women not using HRT, the loss of height would have to be very strongly associated with lower OPG levels among the non-participants in these groups. We believe that this is unlikely and that it is more plausible that non-participation may have weakened the actual relationship.

We conclude that height loss is positively associated with OPG in men and in postmenopausal women not using HRT. No relationship is found in premenopausal women or postmenopausal women taking HRT. We call for longitudinal studies on the relationship between the OPG/RANKL system and incident vertebral fracture.

References

Gunnes M, Lehmann EH, Mellstrøm D, Johnell O. The relationship between anthropometric measurements and fractures in women. Bone. 1996;19(4):407–13.

Tobias JH, Hutchinson AP, Hunt LP, McCloskey EV, Stone MD, Martin JC, et al. Use of clinical risk factors to identify postmenopausal women with vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(1):35–43.

Krege JH, Siminoski K, Adachi JD, Misurski DA, Chen P. A simple method for determining the probability a new vertebral fracture is present in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(3):379–86.

Siminoski K, Jiang G, Adachi JD, Hanley DA, Cline G, Ioannidis G, et al. Accuracy of height loss during prospective monitoring for detection of incident vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(4):403–10.

Siminoski K, Warshawski RS, Jen H, Lee K. The accuracy of historical height loss for the detection of vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(2):290–6.

Ismail AA, Cooper C, Felsenberg D, Varlow J, Kanis JA, Silman AJ, et al. Number and type of vertebral deformities: epidemiological characteristics and relation to back pain and height loss. European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9(3):206–13.

Huang C, Ross PD, Lydick E, Davis JW, Wasnich RD. Contributions of vertebral fractures to stature loss among elderly Japanese-American women in Hawaii. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11(3):408–11.

Khosla S. Minireview: the OPG/RANKL/RANK system. Endocrinology. 2001;142(12):5050–5.

Teitelbaum SL. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science. 2000;289(5484):1504–8.

Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, Yamaguchi K, Kinosaki M, Mochizuki S, et al. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95(7):3597–602.

Vega D, Maalouf NM, Sakhaee K. CLINICAL review #: the role of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB (RANK)/RANK ligand/osteoprotegerin: clinical implications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(12):4514–21.

Sorkin JD, Muller DC, Andres R. Longitudinal change in the heights of men and women: consequential effects on body mass index. Epidemiol Rev. 1999;21(2):247–60.

Drøyvold WB, Nilsen TI, Krûger O, Holmen TL, Krokstad S, Midthjell K, et al. Change in height, weight and body mass index: longitudinal data from the HUNT study in Norway. Int J Obes. 2006;30(6):935–9.

Forsmo S, Hvam HM, Rea ML, Lilleeng SE, Schei B, Langhammer A. Height loss, forearm bone density and bone loss in menopausal women: a 15-year prospective study. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study, Norway. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(9):1261–9.

Yoshimura N, Kinoshita H, Takijiri T, Oka H, Muraki S, Mabuchi A, et al. Association between height loss and bone loss, cumulative incidence of vertebral fractures and future quality of life: the Miyama study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(1):21–8.

Jørgensen L, Vik A, Emaus N, Brox J, Hansen JB, Mathiesen E, et al. Bone loss in relation to serum levels of osteoprotegerin and nuclear factor-kappaB ligand: the Tromsø Study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;21(6):931–8.

Mezquita-Raya P, de la Higuera M, Garcia DF, Alonso G, Ruiz-Requena ME, de Dios LJ, et al. The contribution of serum osteoprotegerin to bone mass and vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(11):1368–74.

Jørgensen HL, Kusk P, Madsen B, Fenger M, Lauritzen JB. Serum osteoprotegerin (OPG) and the A163G polymorphism in the OPG promoter region are related to peripheral measures of bone mass and fracture odds ratios. J Bone Miner Metab. 2004;22(2):132–8.

Browner WS, Lui LY, Cummings SR. Associations of serum osteoprotegerin levels with diabetes, stroke, bone density, fractures, and mortality in elderly women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(2):631–7.

Schett G, Kiechl S, Redlich K, Oberhollenzer F, Weger S, Egger G, et al. Soluble RANKL and risk of nontraumatic fracture. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1108–13.

Jørgensen L, Joakimsen O, Mathiesen EB, Ahmed L, Berntsen GK, Fønnebø V, et al. Carotid plaque echogenicity and risk of nonvertebral fractures in women: a longitudinal population-based study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;79(4):207–13.

McClung B, Parkins N, McClung MR. Comparison of height measurements made with Harpenden stadiometer and a wall-mounted ruler on patients with vertebral compressiom fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12(Suppl 1):S268.

Berntsen GK, Tollan A, Magnus JH, Søgaard AJ, Ringberg T, Fønnebø V. The Tromsø Study: artifacts in forearm bone densitometry-prevalence and effect. Osteoporos Int. 1999;10(5):425–32.

Berntsen GK, Fønnebø V, Tollan A, Søgaard AJ, Joakimsen RM, Magnus JH. The Tromsø study: determinants of precision in bone densitometry. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(11):1104–12.

Auyeung TW, Lee JS, Leung J, Kwok T, Leung PC, Woo J. Effects of height loss on morbidity and mortality in 3145 community-dwelling Chinese older women and men: a 5-year prospective study. Age Ageing. 2010;39(6):699–704.

Abrahamsen B, Hjelmborg JV, Kostenuik P, Stilgren LS, Kyvik K, Adamu S, et al. Circulating amounts of osteoprotegerin and RANK ligand: genetic influence and relationship with BMD assessed in female twins. Bone. 2005;36(4):727–35.

Han KO, Choi JT, Choi HA, Moon IG, Yim CH, Park WK, et al. The changes in circulating osteoprotegerin after hormone therapy in postmenopausal women and their relationship with oestrogen responsiveness on bone. Clin Endocrinol. 2005;62(3):349–53.

Indridason OS, Franzson L, Sigurdsson G. Serum osteoprotegerin and its relationship with bone mineral density and markers of bone turnover. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(4):417–23.

Khosla S, Arrighi HM, Melton LJ III, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, Dunstan C, et al. Correlates of osteoprotegerin levels in women and men. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13(5):394–9.

Kim JG, Kim JH, Lee DO, Kim H, Kim JY, Suh CS, et al. Changes in the serum levels of osteoprotegerin and soluble receptor activator for nuclear factor kappaB ligand after estrogen-progestogen therapy and their relationships with changes in bone mass in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2008;15(2):357–62.

Kudlacek S, Schneider B, Woloszczuk W, Pietschmann P, Willvonseder R. Serum levels of osteoprotegerin increase with age in a healthy adult population. Bone. 2003;32(6):681–6.

Liu JM, Zhao HY, Ning G, Zhao YJ, Chen Y, Zhang Z, et al. Relationships between the changes of serum levels of OPG and RANKL with age, menopause, bone biochemical markers and bone mineral density in Chinese women aged 20–75. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;76(1):1–6.

Oh KW, Rhee EJ, Lee WY, Kim SW, Oh ES, Baek KH, et al. The relationship between circulating osteoprotegerin levels and bone mineral metabolism in healthy women. Clin Endocrinol. 2004;61(2):244–9.

Rogers A, Saleh G, Hannon RA, Greenfield D, Eastell R. Circulating estradiol and osteoprotegerin as determinants of bone turnover and bone density in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(10):4470–5.

Szulc P, Hofbauer LC, Heufelder AE, Roth S, Delmas PD. Osteoprotegerin serum levels in men: correlation with age, estrogen, and testosterone status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(7):3162–5.

Uemura H, Yasui T, Miyatani Y, Yamada M, Hiyoshi M, Arisawa K, et al. Circulating profiles of osteoprotegerin and soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand in post-menopausal women. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008;31(2):163–8.

Samelson EJ, Broe KE, Demissie S, Beck TJ, Karasik D, Kathiresan S, et al. Increased plasma osteoprotegerin concentrations are associated with indices of bone strength of the hip. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1789–95.

Ueland T, Yndestad A, Oie E, Florholmen G, Halvorsen B, Froland SS, et al. Dysregulated osteoprotegerin/RANK ligand/RANK axis in clinical and experimental heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111(19):2461–8.

Yano K, Tsuda E, Washida N, Kobayashi F, Goto M, Harada A, et al. Immunological characterization of circulating osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor: increased serum concentrations in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(4):518–27.

Oh KW, Rhee EJ, Lee WY, Kim SW, Baek KH, Kang MI, et al. Circulating osteoprotegerin and receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand system are associated with bone metabolism in middle-aged males. Clin Endocrinol. 2005;62(1):92–8.

Stern A, Laughlin GA, Bergstrøm J, Barrett-Connor E. The sex-specific association of serum osteoprotegerin and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB legend with bone mineral density in older adults: the Rancho Bernardo study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156(5):555–62.

Min H, Morony S, Sarosi I, Dunstan CR, Capparelli C, Scully S, et al. Osteoprotegerin reverses osteoporosis by inhibiting endosteal osteoclasts and prevents vascular calcification by blocking a process resembling osteoclastogenesis. J Exp Med. 2000;192(4):463–74.

Kong YY, Yoshida H, Sarosi I, Tan HL, Timms E, Capparelli C, et al. OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature. 1999;397(6717):315–23.

Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T, et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93(2):165–76.

Cummings SR, San MJ, McClung MR, Siris ES, Eastell R, Reid IR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(8):756–65.

Khosla S. Update in male osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(1):3–10.

Mellström D, Vandenput L, Mallmin H, Holmberg AH, Lorentzon M, Oden A, et al. Older men with low serum estradiol and high serum SHBG have an increased risk of fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(10):1552–60.

LeBlanc ES, Nielson CM, Marshall LM, Lapidus JA, Barrett-Connor E, Ensrud KE, et al. The effects of serum testosterone, estradiol, and sex hormone binding globulin levels on fracture risk in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(9):3337–46.

Jiang G, Luo J, Pollintine P, Dolan P, Adams MA, Eastell R. Vertebral fractures in the elderly may not always be “osteoporotic”. Bone. 2010;47(1):111–6.

Acknowledgments

The study was financed through the Northern Norway Regional Health Authority.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jørgensen, L., Hansen, JB., Brox, J. et al. Serum osteoprotegerin levels are related to height loss: The Tromsø Study. Eur J Epidemiol 26, 305–312 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-011-9555-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-011-9555-8