Abstract

This paper aims to study the effects of a possible Russia-European Union (EU) free-trade agreement (FTA), in Russia itself and in the other Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries. The paper also presents estimations of the effects of external shocks on the CIS country that has closest trade relations with Russia, the Republic of Belarus. The paper is organized as follows. Section 1 starts with a brief description of the computable general equilibrium (CGE) model used herein. The current status of trade flows between the EU, Russia, and the CIS are presented in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3, the effects of a EU-Russia FTA are simulated on a benchmark of an enlarged EU and a Russia that is a World Trade Organization (WTO) member. Section 4 describes the trade relations between Russia and Belarus and the effects of a gas price shock. The work concludes that a FTA with the EU would yield positive results for Russia and Belarus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

CIS stands for the Commonwealth of Independent States, the loose organization that includes most of the countries form the former Soviet Union, bar the Baltic States that became members of the EU in 2004. Its members are Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. One must note that Turkmenistan discontinued its permanent membership of the CIS as of 26 August 2005, and is now an associate member, that Ukraine never actually ratified the CIS Treaty, and that on 12 August 2008 the Georgian Government announced it would leave the CIS, a decision later approved by the Georgian Parliament. In this paper, the acronym Former Soviet Union (FSU) will be used interchangeably with CIS.

Russia and Belarus have formed a FTA between the two countries. There is a—still incomplete—customs union between the two countries, as part of a process to eventually constitute a State Union of the two countries, which would include, among other features, a common currency. This union and the steps towards it (notably, the common currency) have been repeatedly delayed.

As of 1 May 2004, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia (the so-called New Member States, or NMS) became fully fledged members of European Union, while Bulgaria and Romania entered the EU in 2007. Nevertheless, this paper only looks at the EU-25 (i.e., up to the 2004 enlargement).

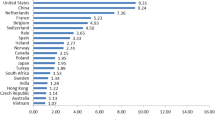

Bar Belgium and Luxembourg, and Cyprus and Malta, which are presented as aggregates.

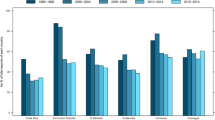

The figures present trade flows as if the EU 25 already existed since the early 1990s.

The CIS have relatively less liberalized trade relations with the EU when compared with other neighboring regions, namely the Mediterranean (MEDA) countries part of the so-called Barcelona Process, which have FTAs with the EU. Dodini and Vinhas de Souza (2006) show that these FTAs with the EU are much more effective in increasing openness (measured by imports plus exports as share of GDP) and in reducing tariffs in the MEDA partner countries than multilateral liberalization (proxied by WTO membership).

All the simulations in this section were done with the GEMPACK and RunGTAP softwares (Pearson and Horridge 2005).

The Russian Federation applied for membership in the WTO in 1993, around 15 years ago. Negotiations on the terms of accession are still ongoing. We estimate the effects of Russian WTO entry using the Russian-agreed WTO tariff bindings, taken from the official Russian WTO accession website (http://www.wto.ru: those tariffs are shown in the Appendix). There are very limited sector reductions foreseen in those proposed bindings, and the final proposed average bind tariff is 12.8%, which is +17.4% above the current level.

The aggregation of the whole of the agriculture and husbandry subsectors in a single sector in our simulation runs prevents an analysis of the performance of the individual subsectors.

Their model is what Schiff and Winters (2003) would classify as a hybrid second/third generation CGE model, as it uses increasing returns to scale, imperfect competition, and long-run dynamics. Still today, most of the CGE models used are what one could call first-generation CGE models (perfect competition with heterogeneous goods). First-generation CGEs (including the GTAP) typically find gains from regional trade integration to be around 1% of GDP, whereas second-generation models find values of 2–3% of GDP, and third-generation models around 5% of GDP. Nevertheless, this is not always the case: GTAP-based estimations of the gains from EU accession for the new EU member states are of the order of 6% of GDP for the smaller NMS (Vinhas de Souza 2004), and the positive effects of unilateral trade liberalization by Belarus, using a small CGE (Vinhas de Souza and Bakanova 2002) are estimated to be close to 6% of GDP.

Although the investment rate in Russia used to be well below the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average of around 22%, it reached 25% in 2007, as fixed investment growth since 2000 has actually been substantially above the GDP growth rate in each year except for 2002 (with a 10.5% average growth rate during 2000–2005).

Gas export volumes to the EU increased over the period (albeit falling in 2005), but total gas export volumes, including to CIS countries, fell substantially. As gas prices for sales to non-CIS countries are usually significantly higher than for CIS countries, this implied increasing export revenues for Russia, in spite of falling export volumes.

Preliminary CGE estimations by the authors (not shown here) show that an export demand shock of −20% could have a −49% welfare equivalent effect for Belarus.

The average price of Urals for Belarus in 2005 was USD 29.1 per barrel, which is well below the average world price of around USD 50.4 per barrel. In December 2006, this offshore tax avoidance scheme with oil duties was ended by Russia, and gas prices also significantly increased.

For details see Gatovsky and Kashinskaya (2006).

In 2004–2006 the natural gas price on the border for Belarus was USD 46.68 per 1,000 cubic meters; by the second quarter of 2008, it had reached USD 128

A CGE or a structural model are the adequate modeling instruments to evaluate a complex shock such as the relative price change of a basic energy commodity: partial or single-equation estimations can, in the best of cases, provide only a very limited, short-run picture. The model used here was developed for assessment of the economic effects of Belarus’s accession to the WTO; the model is programmed in General Algebraic Modeling System/Mathematical Programming System for General Equilibrium analysis (GAMS/MPSGE). For details see Pavel and Tochitskaya (2005).

Vinhas de Souza (2006), using a small structural model, finds a comparable short-run GDP loss of 2.2% for Ukraine from a gas price increase to USD 230.

Once again, this is only the effect of the gas price shock: a combined gas and oil price shock could conceivably have even larger short-run effects.

Real GDP effects have been much smaller than those, since the oil and gas prices increases of late 2006. Lysenko and Vinhas de Souza (2007) estimate that these predicted negative growth effects have so far not materialized, largely owing to the accumulation of private and quasiprivate external debt, which have cushioned the shock in Belarus.

The same proviso applies as previously concerning the nondynamic nature of the CGE model in this section (as for the GTAP in the previous one). A true dynamic model, on one hand, could estimate even larger losses, but, on the other hand, would also estimate the welfare-enhancing switch away to sectors that have real comparative advantages, caused by the relative price change. The final long-run result would likely be a net welfare increase, especially in a scenario of comprehensive external liberalization and reform, as the economy would move to its long-run international comparative advantage position.

References

Alekseev A, Sokolov D, Tourdyeva N, Yudaeva K (2004) Estimating the effects of EU enlargement, WTO accession and the formation of FTA with EU or CIS on the Russian economy. Mimeo, NES-CEFIR

Dodini M, Vinhas de Souza L (2006) Arab countries’ participation in the multilateral trade system at the critical juncture of the Doha development agenda. Mimeo, European Commission, Brussels

Gatovsky A, Kashinskaya I (2006) Belarusian trade in energy goods. Mimeo

Hertel T, Tsigas M (1997) Structure of the GTAP model, chap 2. In: Hertel T (ed) Global trade analysis: modeling and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

IMF (2005) Republic of Belarus: selected issues, country report no. 05/217. Washington, DC

Jesper J, Rutherford T, Tarr D (2002) Economy-wide effects of Russia’s accession to the WTO. In: SIDA-CEFIR conference, June 24–25

Lysenko T, Vinhas de Souza L (2007) The effects of energy price shocks on growth and macroeconomic stability in selected energy-importing CIS countries, occasional paper no. 30. European Commission, Brussels, pp 3–23

Pavel F, Tochitskaya I (2005) The economic impact of Belarus accession to the WTO: a quantitative assessment. In: International conference proceedings “Belarus WTO accession: problems and perspectives”, Minsk. www.research.by

Pearson K, Horridge M (2005) Hands-on computing with RunGTAP and WinGEM to introduce GTAP and GEMPACK. Mimeo

Schiff M, Winters L (2003) Regional integration and development. World Bank and Oxford University Press

Sulamaa P, Widgren M (2002) EU enlargement and the opening of Russia: lessons from the GTAP reference model. The research institute of the Finnish Economy, no. 11

Tochitskaya I (2003) Regional economic integration and technology diffusion: the case of Belarus. ECOWEST

Vinhas de Souza L (2004) A wider Europe: trade relations between an enlarged EU and the Russian federation, working papers series, no. 249. CASE, Poland

Vinhas de Souza L (2006) Effects of gas price increases in CIS countries: the case of Ukraine. Research note. European commission, Brussels

Vinhas de Souza L (2008) Russia: a different country. CEPS paperback books series. CEPS, Brussels, Belgium. http://shop.ceps.eu/BookDetail.php?item_id=1652

Vinhas de Souza L, Bakanova M (2002) Trade and growth under limited liberalization: the case of Belarus, Tinbergen institute discussion paper no. TI 2002-053/2. The Netherlands

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The views expressed here are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent those of organizations to which the authors are or were linked to. All usual disclaimers apply.

Appendix

Appendix

Overall Russian weighted averages of the effective, initial, and final bound rates of import tariffs (using the 2000 imports statistics)

Effective tariff rate (January 2001, %) | Initial bound rate of the import tariff (%) | Final bound rate of the import tariff, %, and % change on current tariff | |

|---|---|---|---|

Weighted averages | |||

Agricultural goods | 14.70 | 34.71 | 25.11 (+70.8%) |

Industrial goods | 9.73 | 14.32 | 9.84 (+1.13) |

All the trade nomenclature engaged in the foreign economic activity | 10.92 | 19.18 | 12.82 (+17.4%) |

Weighted averages on the large groups of goods | |||

Alimentary goods and agricultural raw materials (with the exception of textiles) | 14.77 | 34.86 | 25.16 (+70.4) |

Mineral production, including fuels and energy sources | 5.43 | 11.06 | 5.43 (+0%) |

Chemical industry production, rubber | 8.48 | 10.22 | 6.09 (−28.2%) |

Wood, and cellulose and paper goods | 8.73 | 14.62 | 7.85 (−10.1%) |

Textiles, apparel, and shoes | 11.69 | 18.31 | 12.37 (+5.8%) |

Precious stones, and precious metals and goods made out of them | 20.00 | 25.00 | 20.00 (0%) |

Metals and metal goods | 11.35 | 19.29 | 11.70 (+3.1%) |

Machinery, equipment, and means of transportation | 9.48 | 14.83 | 8.75 (−7.7%) |

Gypsum, glass, and ceramics | 15.51 | 20.18 | 14.39 (−7.22%) |

Raw materials for tanning industry, and furs and goods made out of them | 14.94 | 21.13 | 13.25 (−11.3%) |

Other (clocks, musical instruments, other items) | 18.04 | 20.20 | 16.43 (−8.9%) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tochitskaya, I., Vinhas de Souza, L. Trade relations between an enlarged EU and the Russian Federation, and its effects in Belarus. Econ Change Restruct 42, 1–24 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-008-9064-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-008-9064-2