Abstract

The global warming potential (GWP) is widely used in policy analysis, national greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting, and technology life cycle assessment (LCA) to compare the impact of non-CO2 GHG emissions to the impact of CO2 emissions. While the GWP is simple and versatile, different views about the appropriate choice of time horizon—and the factors that affect that choice—can impede decision-making. If the GWP is viewed as an approximation to a climate metric that more directly measures economic impact—the global damage potential (GDP)—then the time horizon may be viewed as a proxy for the discount rate. However, the validity of this equivalence rests on the theoretical basis used to equate the two metrics. In this paper, we develop a new theoretical basis for relating the GWP time horizon and the economic discount rate that avoids the most restrictive assumptions of prior studies, such as an assumed linear relationship between economic damages and temperature. We validate this approach with an extensive set of numerical experiments using an up-to-date climate emulator that represents state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks. The numerical results largely confirm the theoretical finding that, under certain reasonable assumptions, time horizons in the GWP of 100 years and 20 years are most consistent with discount rates of approximately 3% and 7% (or greater), respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Climate metrics are widely used in policy analysis, national greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting, and technology life cycle assessment (LCA) to convert emissions of non-CO2 GHGs into CO2-equivalent units. In general, a climate metric quantifies the climate impacts of a unit emission of a GHG relative to the impacts of a unit emission of CO2 (Myhre et al. 2013a). There is considerable debate in the literature about the preferred climate metric, as evident from the large number of alternative climate metrics proposed over the last three decades (Lashof and Ahuja 1990; Fankhauser 1994; Kandlikar 1995; Hammitt et al. 1996; Fuglestvedt et al. 2003; Shine et al. 2005, 2007; Gillett and Matthews 2010; Peters et al. 2011; Boucher 2012; Azar and Johansson 2012; Tol et al. 2012; Tanaka et al. 2013; Edwards and Trancik 2014; Levasseur et al. 2016). Some examples of metrics widely used in decision-making include the global warming potential (GWP) (Lashof and Ahuja 1990), global temperature change potential (GTP) (Shine et al. 2005), and global damage potential (GDP) (Fankhauser 1994; Kandlikar 1995; Hammitt et al. 1996).

Climate metrics differ in multiple respects, such as (1) whether the metric measures physical impacts such as radiative forcing, temperature change, sea level rise, or economic impacts; (2) whether it measures cumulative or end point impacts; and (3) whether it considers a fixed time horizon or fixed end year (Mallapragada and Mignone 2017). Despite the large number of proposed metrics, the GWP remains the climate metric most widely used in policy analysis, national GHG accounting, and LCA. However, it is well-known that the choice of time horizon in the GWP can affect results considerably. For example, in the case of methane, the GWP-100 (corresponding to a time horizon of 100 years) is approximately 30, whereas the GWP-20 (corresponding to a time horizon of 20 years) is approximately 85 (Myhre et al. 2013a). This sensitivity of results to the choice of time horizon has led to calls to perform more robust sensitivity analysis whenever the GWP is used (Cherubini et al. 2016; Levasseur et al. 2016; Cherubini and Tanaka 2016; Ocko et al. 2017).

While sensitivity analysis can be informative, such an approach does not directly address the issue of whether some choices for the time horizon may be more consistent with other analytical choices, such as those used in economic cost-benefit analysis. To address the issue of consistency more directly, one may treat the GWP as an approximation to the GDP, which measures impact further along the casual chain and uses discounting, rather than truncation, to make the relevant integral converge.Footnote 1 As noted by Kandlikar (Kandlikar 1995), “when the problem is cast into an economic framework the choice of time horizon is converted into a choice of an appropriate discount rate, which is a well-defined problem area in economic literature.” Importantly, if the GWP and GDP effectively measure the same thing (with one an approximation of the other), then it should be possible to find a time horizon in the GWP and a discount rate in the GDP such that the two metrics are equal. Converting the choice of time horizon into a choice about the discount rate in this way does not eliminate subjectivity from the problem, but it does at least make clear what the choice is actually about, namely economic time preference.

Several studies have since performed the numerical experiments implied by the insight above. For example, Fuglestvedt et al. (Fuglestvedt et al. 2003) estimated that, depending on whether economic damages vary quadratically or cubically with temperature, a discount rate of 1.75% or 2.9%, respectively, would be consistent with the GWP-100. Similarly, Boucher (Boucher 2012) estimated that a discount rate of 2% approximates the GWP-100. More recently, Sarofim and Giordano (Sarofim and Giordano 2018) performed a similar analysis relating the GWP time horizon to the GDP discount rate over a larger set of parameter values, effectively tracing out a continuous relationship between the two parameters. They conclude that a discount rate of approximately 3% most closely approximates the GWP-100.

Although these studies suggest an approach for relating the choice of time horizon in the GWP to the choice of discount rate in the GDP, several challenges remain. First, prior studies offering a theoretical basis for the approximate equivalence between the GWP and GDP (upon which the numerical studies conceptually rely) make several strong assumptions. For example, both Tol et al. (Tol et al. 2012) and Marten and Newbold (Marten and Newbold 2012) show that the GWP approximates the GDP if the discount rate is assumed to be zero, the time horizon of the GDP is set equal to that of the GWP, and damages are assumed to vary linearly with temperature. This set of assumptions is quite restrictive. Marten and Newbold (Marten and Newbold 2012) acknowledge that “the above set of simplifying assumptions is not necessary for the social cost of gas X to be equal to its GWP multiplied by the social cost of carbon dioxide; it is simply the most straightforward set of sufficient conditions.”

Second, perhaps because of the limitations of the existing theory, no study to date has explicitly derived an expression for the relationship between the discount rate and the time horizon against which numerical estimates could be compared. Without such a theoretical basis, it is challenging to develop intuition for why these parameters vary with one another in the way that is observed (in numerical experiments) and to evaluate the conditions under which the theory is valid. Finally, studies to date that have evaluated the GWP and GDP numerically do not incorporate state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks (Millar et al. 2017). These feedbacks are particularly relevant to the GDP, which unlike the GWP, does not assume a constant climate background state. Including such feedbacks alters the agreement between theory and numerical results, as well as the sensitivity of the numerical results to several of the input assumptions, such as the baseline emissions scenario, economic growth trajectory, and damage function exponent.

In this paper, we address the above-mentioned shortcomings in the literature comparing the GDP and GWP in order to inform the choice of time horizon used in the GWP. First, we develop a theoretical framework relating the GWP and GDP that requires fewer restrictive assumptions than prior studies. Specifically, we assume neither that the discount rate is zero nor that economic damages vary linearly with temperature. Second, we use this new formulation to develop a simple theoretical relationship between the choice of time horizon in the GWP and the choice of economic discount rate. Finally, we utilize a climate emulator capable of capturing climate-carbon cycle feedbacks (Millar et al. 2017; The National Academies 2017; Smith et al. 2018) to numerically validate the theory across a wide range of climate and economic assumptions, including baseline emissions scenario, representation of climate-carbon cycle feedbacks, methane lifetime, equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS), damage function exponent, and the economic growth trajectory.

2 Theoretical framework

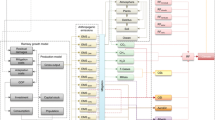

The global damage potential (GDP) is expressed as the ratio of the social cost of a given greenhouse gas (GHG) to the social cost of CO2 (SCC), where the social cost of a GHG measures the (discounted) cumulative economic damage of that GHG. The global warming potential (GWP) is expressed as the ratio of the absolute global warming potential (AGWP) of a given GHG to the AGWP of CO2, where the AGWP of a GHG measures the cumulative radiative forcing of that GHG. While the GDP and GWP both measure the climate impact of a given GHG relative to CO2—and while both are cumulative measures of impact—they estimate impact at different points along the causal chain. Specifically, the social cost calculation underlying the GDP requires four steps to translate emissions into climate damages: (1) translation from emissions to atmospheric concentration, (2) translation from atmospheric concentration to radiative forcing, (3) translation from radiative forcing to temperature change, and (4) translation from temperature change to economic damages. On the other hand, the AGWP calculation underlying the GWP only requires the first two steps. Thus, the GDP measures impacts further along the causal chain, which is arguably closer to the metric that matters to society, but at the same time, is characterized by greater uncertainty associated with the final two steps in the chain (Tanaka et al. 2010).

In this section, we first evaluate the conditions under which the GWP approximates the GDP, specifically focusing on parameter choices for each metric that would render the two metrics mathematically equivalent (Sect. 2.1). Given the approximations required to make this exercise analytically tractable, we then consider the sensitivity of the theoretical result to particular assumptions and the extent to which the theoretical formulation is generalizable (Sect. 2.2).

2.1 Equivalence of the GDP and GWP

To evaluate the conditions under which the GWP approximates the GDP, we begin with the mathematical definition of the social cost of a GHG, make several simplifying assumptions to develop a reduced form expression, and then use this to define a reduced form expression for the GDP. We perform a similar set of steps to arrive at a reduced form expression for the GWP. From these relationships, it is straightforward to solve for parameter choices that would equate the reduced-form version of the GDP with the reduced-form version of the GWP. The validity of the simplifying assumptions can be tested by numerically evaluating the GDP and GWP without the simplifying assumptions and comparing results. This numerical validation is discussed in the following section.

The current value for the social cost of a greenhouse gas (X) is defined as the change in total present value of climate damages (Z) per unit increase in emissions of X in the present year (E0). To specify the social cost of X (SCX), it is necessary to first define the present value of total damages (Z):

In this expression, G(t) is the total economic output (in dollars), D(t) is the economic damage per unit output, and r is the discount rate.Footnote 2 The definition of SCX is thus:

The final expression on the right-hand side assumes that the economic growth path, G(t), is not affected by climate damages (i.e., that it is not a function of E0). The relationship between damages per unit output (D(t)) and changes in current year emissions (E0) is mediated by several climate system responses. Specifically, damages per unit output (D(t)) are a function of temperature (T(t)), temperature is a function of radiative forcing (F(t)), forcing is a function of the concentration of X (C(t)), and the concentration of X is a function of emissions of X. In this case, we are interested in the response to an initial pulse emission (E0) of X, above some background emissions.

CO2 forcing is typically assumed to vary logarithmically with concentration, whereas forcing from methane and N2O is often assumed to vary with the square root of concentration (Myhre et al. 1998; Etminan et al. 2016). On the other hand, damages are often assumed to vary quadratically with temperature (Nordhaus 2017). Following Kopp and Mignone (Kopp and Mignone 2013), we may assume that the convexity of the damage function (related to the first term on the right-hand side) is approximately offset by the concavity of the forcing-concentration relationship (related to the third term on the right-hand side) such that the product of the first three terms on the right-hand side is approximately constant.

The validity of Eq. 4 and the constant of proportionality will depend on the GHG, since the instantaneous radiative efficiency (the third term on the left-hand side of Eq. 4) varies by GHG. The first and third terms of the left-hand side of Eq. 4 are shown for all four Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs), developed for use by the IPCC (International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis 2009; Meinshausen et al. 2011), in Fig. S 2. Note that this approximation could worsen if the exponent of the damage function changes (which will be explored in numerical calculations). The dependence of the concentration on the initial emission pulse is described by an atmospheric decay function, which also depends on the GHG being considered.

The assumption of a single, state-independent atmospheric decay time constant (dX) is generally not sufficient for CO2 (and will be relaxed in numerical calculations), but it is useful for developing a reduced-form solution. In this case, the last term on the right-hand side of Eq. 3 becomes

If economic output is assumed to be growing at a constant rate, then

Substituting Eqs. 4, 6, and 7 into Eq. 2 yields

The expression in Eq. 8 can be used to approximate the social cost of any GHG. The GDP for any GHG (X) can thus be found by taking the ratio of SCX to the social cost of CO2 (SCC).

While the constants KX and KC in Eq. 8 reflect a combination of economic and climate system parameters (the first three terms on the right-hand side of Eq. 4), the most significant difference between CO2 and another GHG (among these parameters) is the difference in initial radiative efficiencies (RC and RX), so K has been replaced by R in Eq. 9, where \( {R}_{\mathrm{X}}\equiv \frac{\partial F\left(t=0\right)}{\partial C} \).

To compare the GDP to the GWP, it is necessary to approximate the GWP in a similar fashion, starting with the definition of the AGWP for a greenhouse gas (X). The AGWP for X is defined as

In this expression, TH is the time horizon over which the radiative forcing impact is aggregated. For eventual comparison with the GDP, it is useful to make the following approximation:

Using this approximation, Eq. 10 becomes

The expression in Eq. 12 can be used to approximate the AGWP for any GHG and for any TH. The GWP for any GHG (X) can thus be found by taking the ratio of AGWPX to the AGWP for CO2.

Equations 9 and 13 are identical if and only if

This expression provides a way to translate between the time horizon used in the GWP calculation and the discount rate used in the GDP calculation. For example, if the long-run real economic growth rate is assumed to be 2% per year and the discount rate is assumed to be 3%, then the corresponding value of the time horizon (TH) would be 100 years. Alternatively, if the discount rate is instead assumed to be 7%, then the corresponding value of the time horizon would be 20 years.

Equation 14 can also be expressed in terms of other fundamental economic parameters using the well-known Ramsey formula (Ramsey 1928). The Ramsey formula relates the discount rate (r) to the pure rate of time preference (ρ), the coefficient of relative risk aversion (η), and the economic growth rate (g): r = ρ + η·g. Using this relationship, Eq. 14 becomes:

The interpretation of this alternative formulation will be discussed further in Sect. 4.

2.2 Generalizability of the theoretical framework

Before evaluating the theory using numerical experiments in the next section, it is worth considering several aspects of the theoretical approach in more detail: (1) the representation of climate-carbon cycle feedbacks, (2) the sensitivity of results to alternative forcing-concentration relationships, and (3) the generalizability of this approach to other GHGs and climate forcing agents.

Regarding the first aspect, the derivations of the reduced-form relationships for both the GDP and the GWP above do not consider climate-carbon cycle feedbacks. In contrast, when reporting values for the GWP, the IPCC provides values for methane and other forcing agents with and without climate-carbon cycle feedbacks, and such feedbacks are always included for CO2 (Myhre et al. 2013a). Although both feedbacks could be included—by introducing multiple decay time constants for CO2 (Joos et al. 2013) or by adding an additional term to the AGWP for other forcing agents (Collins et al. 2013; Gasser et al. 2017)—doing so introduces complexity without enhancing the key insights of the simple framework. Moreover, these extensions would not alter the expression in Eq. 14 if applied identically to the GWP and GDP. However, these extensions do not fully capture the state-dependence of climate-carbon cycle feedbacks (Millar et al. 2017), which are relevant to the calculation of the GDP, which unlike the GWP, does not assume a fixed climate background state. The numerical model in the following section is better suited to exploring the role of state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks.

Regarding the second aspect, the sensitivity of results to alternative forcing-concentration relationships is relevant in light of recent studies suggesting greater radiative forcing due to methane (Etminan et al. 2016) relative to prior IPCC estimates (Myhre et al. 2013a). In evaluating this sensitivity, it is worth noting that the theoretical derivation above does not assume any particular values for the initial radiative efficiency (RE) of CO2 or other forcing agents (RC and RX, respectively), since the values of these parameters do not affect the equivalence of Eqs. 9 and 13 that yields Eq. 14. The functional form of the forcing-concentration relationship affects the GDP, but not the GWP, since the latter assumes a fixed climate background state, i.e., constant REs. The dependence of the GDP on the functional form of the forcing-concentration relationship enters through Eq. 4, which assumes that the concavity of the forcing function approximately offsets the convexity of the damage function. Since recently proposed revisions to the radiative forcing relationships do not significantly alter their functional forms, the theoretical results are not likely to be sensitive to such changes.

Finally, our conclusions regarding the third aspect—the generalizability of the theoretical approach to other GHGs and climate forcing agents—directly follow from the radiative forcing discussion. The theoretical approach is generalizable to the extent that other GHGs or climate forcing agents exhibit a concave forcing-concentration relationship, which is assumed in Eq. 4. This assumption is well justified for methane and N2O—two of the most widely considered GHGs in climate policy analysis—but may not be well justified for other GHGs or aerosols, for which forcing is linear in concentration. That said, under more restrictive conditions, for example, if damages were assumed to be linear in temperature, then Eq. 4 could still hold when forcing is linear in concentration. Thus, the theoretical approach could be extended to a wider set of climate forcing agents under more restrictive conditions than those assumed for methane and N2O.

Although the theoretical framework could be validated for N2O or other climate forcing agents under other conditions, we focus on results for methane in the next section. Prior studies have considered the numerical equivalence between the GWP and GDP for other GHGs (Sarofim and Giordano 2018). Given the focus of this study on evaluating and clarifying the theoretical framework, we believe that a more extensive numerical exploration of a single example such as methane is more informative than a more limited numerical exploration of multiple examples.

3 Numerical results

To evaluate the theoretical result discussed above, we implemented a version of a simple climate emulator—the FAIR model (Millar et al. 2017)—to calculate GDP and GWP across a range of key parameter values and other underlying assumptions. The FAIR model is similar to the box model used to calculate climate metrics in the IPCC AR5 (Myhre et al. 2013a), with an enhancement to represent the effect of state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks on the residence time of CO2 in the atmosphere. The FAIR model was recommended for use in calculating climate metrics by a recent study of the National Academy of Sciences on the social cost of carbon (The National Academies 2017). Although the theoretical formulation is reasonably general, for reasons discussed above, we focus in this section on testing the theory for methane.

We force the model with background emissions for CO2 and CH4, and radiative forcing for all other species, for the historical period through 2500 using the RCPs developed for use by the IPCC (International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis 2009; Meinshausen et al. 2011). We also consider an alternative climate background state by fixing concentrations of CO2 and CH4 as well as radiative forcing from other non-CO2 species. Temperature outcomes are translated to economic damages using the damage function of Nordhaus (Nordhaus 2017), assuming either a constant or time-varying economic growth rate. For the latter, we make the growth rate through 2100 consistent with the central Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP), namely SSP2 (International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis 2016; Fricko et al. 2017). To calculate the current value of GDP and GWP, we perturb emissions by a small amount in the year 2017. Future projected differences in the relevant outcome variables (radiative forcing in the case of GWP or climate-related damages in the case of GDP) are then aggregated according to the metric definition. Further details on the methodology are provided in the supporting information (SI).

We first compare the numerical results to theory using the simplest version of the numerical model, that is, the version whose assumptions most closely adhere to the assumptions in Sect. 2 (see Table 1). These assumptions include (1) constant and variable RE for GWP and GDP, respectively, (2) no state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks, (3) a quadratic damage function, and (4) a constant economic growth rate. In each of the following subsections, we relax key simplifying assumptions to increase realism and evaluate the sensitivity of the agreement between the numerical model and theory to such changes. Specifically, in Sect. 3.1, we examine results for the simplest version of the numerical model and consider alternative assumptions for the time-dependence of RE, including constant REs for both GWP and GDP as well as varying REs for both GWP and GDP. In Sect. 3.2, we consider the sensitivity to the RCP and the role of state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks under such different climate background states. Finally, in Sect. 3.3, we consider the sensitivity to the damage function exponent and to the representation of economic growth. Other sensitivities are examined in the SI, and the full list of sensitivity cases is shown in Table 1.

3.1 Evaluation of the theory with the simplest versions of the numerical model

The assumptions that define the simplest numerical model are described in Table 1 (see column labeled “Simplest numerical model version”). Two alternative specifications of the climate background state may be considered “simplest.” The first assumes constant REs for the GWP and GDP, whereas the second assumes constant REs for the GWP but varying REs for the GDP, which the theory allows. When REs are assumed to be constant, which is implemented by fixing concentrations of CO2 and CH4, Eq. 4 holds by assumption, because none of the component terms are varying.Footnote 3 When REs are allowed to vary, based on concentrations achieved under RCP 4.5, Eq. 4 holds more approximately, with the size of the error dependent on how the concavity and convexity of the component terms offset one another. Comparing these two versions of the model therefore quantifies the size of the potential error introduced by the approximation in Eq. 4. For completeness, we also consider a version that assumes varying REs for both the GDP and GWP as an additional sensitivity case.

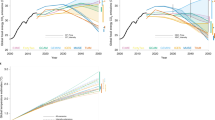

Figure 1 compares the results of these three cases to the theoretical result using two approaches. In the first approach shown in Fig. 1a, we numerically evaluated GDP for a range of discount rates (between 2.4 and 7%). We then estimated GWP using a TH consistent with the specified discount rate according to the theoretical relationship in Eq. 14 assuming an economic growth rate consistent with the numerical model (2.2% per year). The extent of agreement between the calculated GDP and GWP indicates how well the theory performs. In a second approach (Fig. 1b), for each GDP estimated at a given discount rate, we solved for the value of TH such that the GWP equaled the GDP. Plotting the numerically estimated values of TH versus the discount rate and comparing to the theoretical relationship in Eq. 14 provides a direct measure of how well the theory performs.

Comparison between theoretical and numerical approaches for estimating the relationship between the global damage potential (GDP) and the global warming potential (GWP) and associated parameters. Results highlighted for the two simplest versions of the numerical model: Version 1—shown as “GWP RE constant and GDP RE constant” and indicated by red markers—assumes constant background concentrations for CH4 and CO2 resulting in a constant radiative efficiency (RE) ratio for both metrics. Version 2—shown as “GWP RE constant and GDP RE varying” and indicated by green markers—assumes varying REs for the GDP based on concentrations achieved under RCP4.5 but constant REs for the GWP following the definition in Section of 8.SM.11 of IPCC AR5 (Myhre et al. 2013b). For completeness, a third case—shown as “GWP varying and GDP varying” and indicated by blue markers—assumes varying REs for both the GDP and GWP based on concentrations achieved under RCP4.5. Other assumptions in the numerical model (held fixed across these three cases) are described in Table 1. a) Numerically estimated GWP versus GDP, where the GWP time horizon (TH) is consistent with the corresponding GDP parameters. Consistency is determined from Eq. 14, assuming an average economic growth rate of 2.2% per year. Each solid circle represents a different choice of discount rate used in the numerical GDP calculation. The solid gray (y = x) line represents the theoretical relationship between the GDP and GWP when consistent parameters are used, while the shaded area indicates 10% deviation from the theoretical relationship. b) TH that equates the GWP and GDP for a variety of discount rates used to numerically evaluate the GDP (solid circles). The solid gray curve is the theoretical relationship in Eq. 14, assuming an average economic growth rate of 2.2% per year

The simplest versions of the numerical model agree well with theory across a range of discount rates (or TH), as reflected by the proximity of the green and red circles to the y = x parity line in Fig. 1a (up to ± 10% deviation highlighted in gray). Figure 1b shows similar agreement between theory and the simplest versions of the numerical model across a range of discount rates, which can be seen by the proximity of the green and red circles to the gray curve. The numerical results deviate the most from theory at low discount rates (Fig. 1b). This effect is partly due to approximating the infinite integral in the cumulative damages expression (Eq. 2) using a finite integral in the numerical model. Shorter integration time periods in the GDP calculation result in higher GDP values, which in turn yield lower equivalent TH compared to the theoretical relationship (Fig. 1b).

The theoretical relationship between TH and discount rate is derived without making explicit assumptions about the background emissions trajectory but by assuming that the approximation in Eq. 4 holds for both CO2 and CH4. That is, the theory assumes that, in the expression for GDP, the ratio of KX to KC can be approximated as the ratio of the initial instantaneous radiative efficiencies, RX to RC. The approximation in Eq. 4 is reasonable for CO2, because the convexity of the damage function counteracts the concavity of the forcing function (Kopp and Mignone 2013) (compare also panels a and d in Fig. S 2). The approximation in Eq. 4 is less appropriate for CH4, because the forcing function for CH4 is less concave than for CO2 (compare panels b and a in Fig. S 2). However, because the CH4 lifetime is so comparatively short, the approximation is valid over the timescales that matter most, that is, over the period when perturbations in the CH4 concentration are significantly different from zero.

When the error from varying REs is removed by assuming constant concentrations (and therefore constant REs) for both CO2 and CH4, the agreement between the theory and numerical results improves, but only slightly, because the agreement is already quite good in the version that allows varying REs for the GDP (compare red to green circles in Fig. 1). This implies that the error introduced by Eq. 4 is relatively small. On the other hand, when varying REs are applied to both the GDP and GWP calculations, the agreement between theory and numerical results worsens at most discount rates (see blue circles in Fig. 1). Because the concavity of the forcing-concentration relationship is stronger for CO2 than for CH4 when concentrations are increasing (as they are in early periods for most RCPs), the RE of CO2 weakens more rapidly than the RE of CH4, pushing the ratio of the two (CH4 to CO2) above the initial ratio (panel c in Fig. S 2). A larger TH is thus necessary to offset the otherwise greater warming potential of CH4 (i.e., numerator of the GWP) that would follow from a higher RE ratio (blue circles tend to fall above the others in Fig. 1b). It is important to note that, although the GDP calculation allows time-varying REs, this variation is offset by other terms in Eq. 4 for CO2, and it occurs over a period much greater than the perturbation lifetime for CH4, as discussed above. This explains why the case with varying GDP REs matches theory more closely when GWP REs are fixed (green circles) rather than when they are varying (blue circles).

3.2 State-dependence of the relationship between TH and discount rate

This section explores the sensitivity of numerical results and their agreement with theory to the climate background state (RCP) in conjunction with the inclusion or exclusion of state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks. Figure 2 suggests that the relationship between TH and the discount rate is dependent on the climate background state (i.e., RCP) and that this dependence is greater when state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks are turned on (Fig. 2b) than when they are turned off (Fig. 2a). For a given discount rate and RCP, including state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks results in higher estimated values of TH (values in Fig. 2b are higher than those in Fig. 2a). The representation of state-dependent feedbacks in the FAIR model (Millar et al. 2017) affects the numerator (CH4) and denominator (CO2) of the GDP asymmetrically. While CO2 and CH4 emissions both affect CO2 uptake via increasing temperature, CO2 emissions also affect CO2 uptake due to the additional dependency of CO2 uptake on cumulative CO2 emissions. Consequently, with state-dependent feedbacks turned on, the social cost of CO2 increases more than the social cost of CH4, causing the GDP to decline and equivalent TH to increase.

Impact of RCP and state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks on the numerical relationship between the time horizon (TH) in the global warming potential (GWP) and the discount rate in the global damage potential (GDP). The circles show the TH that equates the GWP and GDP for a variety of discount rates used to numerically evaluate the GDP (solid circles). With the exception of background emissions (RCP) and state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks, all other assumptions in the numerical model are consistent with those for the simplest version of the numerical model in Table 1 that assumes constant RE for GWP and varying RE for GDP based on RCP4.5. Green circles in panel a) are identical to those in Fig. 1. The solid gray curve is the theoretical relationship in Eq. 14, assuming an average economic growth rate of 2.2% per year. a) State-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks turned off in the numerical model. b) State-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks turned on in the numerical model

Since the theoretical framework does not account for state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks, the numerically estimated relationships with state-dependent feedbacks turned off more closely adhere to the theoretical relationship at most discount rates. However, Fig. 2a suggests that the numerical relationship between TH and the discount rate is still dependent on the climate background state (i.e., RCP) to some extent. The remaining dependence on RCP follows from the imperfect approximation in Eq. 4. Figure 2a thus indicates the strength of the remaining state-dependence that is not explicitly due to climate-carbon cycle feedbacks.

3.3 Sensitivity to economic growth and damage representation

Figure 3a examines the sensitivity of results to the damage function exponent in conjunction with the inclusion or exclusion of state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks under RCP 4.5. The range of exponents considered here (1.5 to 3) is consistent with other studies focused on climate metrics (e.g., Sarofim and Giordano 2018). When the exponent is increased to 3, the alignment between the numerically estimated values and theory worsens. This is not surprising, since higher damage function exponents erode the approximation in Eq. 4 in which the convexity of the damage function is assumed to approximately offset the concavity of the relationship between radiative forcing and concentration. Changing the damage function exponent to 1.5 is less impactful, in part because the change from 2 to 1.5 is smaller than the change from 2 to 3. In addition, when state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks are included, a smaller damage function exponent preserves the validity of the approximation in Eq. 4, because climate-carbon cycle feedbacks introduce additional convexity (Kopp and Mignone 2013). For example, in Fig. 3a, the numerical results using an exponent of 1.5 with feedbacks turned on (top of the red shaded area) are similar to the results using an exponent of 2 with feedbacks turned off (green circles) over a range of discount rates.

Impact of damage function representation and economic growth on the numerical relationship between the time horizon (TH) in the global warming potential (GWP) and the discount rate in the global damage potential (GDP). The circles show the TH that equates the GWP and GDP for a variety of discount rates used to numerically evaluate the GDP. Shaded areas represent variation in numerical model outputs due to inclusion and exclusion of state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks, with the top of the shaded areas representing values with such feedbacks turned on, and the bottom of the shaded areas (also shown by solid circles) representing values with such feedbacks turned off. With the exception of damage exponents (a), the economic growth rate (b), and state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks, all other assumptions in the numerical model are consistent with those for the simplest version of the numerical model in Table 1 that assumes constant RE for GWP and varying RE for GDP based on RCP4.5. Green circles in both panels are identical to those in Fig. 1. The solid gray curve is the theoretical relationship in Eq. 14, assuming an average economic growth rate of 2.2% per year. a) Effect of varying damage function exponent (1.5, 2, 3). b) Effect of varying economic growth assumptions (constant or variable)

Figure 3b shows the sensitivity of results to the economic growth trajectory, assuming either a constant or variable growth rate, under RCP 4.5. The constant economic growth rate assumption—the assumption in the simplest versions of the numerical model—is based on the average growth rate for the first 100 years of SSP2, which is approximately 2.2% per year. As a potentially more realistic alternative, we assume that the economic growth trajectory follows the central Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP), namely SSP2 (International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis 2016; Fricko et al. 2017) through 2100. We extrapolate economic growth beyond 2100 by assuming that the economic growth rate approaches a constant value of 1% in the long run (see Fig. S 4). The constant economic growth rate assumption yields a better match between numerical results and theory (green circles in Fig. 3b), which is not surprising since the theory also assumes a constant growth rate. At low discount rates, the GDP calculation captures economic growth beyond the first 100 years, leading to an average growth rate that is lower than 2.2% per year. This lower long-run growth rate affects the social cost of CO2 more than methane, increasing the GDP and decreasing the equivalent TH (blue circles in Fig. 3b).

Two additional sensitivities are considered in the Supporting Information. Figure S 5 considers the effect of changing the ECS. The choice of ECS has little effect on the relationship between TH and discount rate because the temperature response affects the values of the social costs of both CO2 and CH4, leaving the GDP (the ratio of the social costs) largely unchanged. Figure S 6 considers the effect of changing the perturbation lifetime of methane. Decreasing this time constant to align projected methane values with observed concentrations over the historical period generally has a small effect on results, as shown in Fig. S 6, because the methane lifetime affects both the GWP and GDP. The largest effect of changing the methane lifetime, most visible at low discount rates, follows from the state-dependence in Eq. 4. Changing the methane lifetime changes the way that the component terms in Eq. 4 offset one another. This effect largely disappears if the GWP and GDP are calculated with fixed REs (approximately constant climate background state), as shown in Fig. S 7.

4 Discussion and conclusions

This study makes three important contributions to the literature on climate metrics. First, it provides a theoretical basis relating the GWP and GDP that is less restrictive than prior theoretical formulations. Specifically, this approach does not require one to assume that the discount rate is zero, nor does it require economic damages to scale linearly with temperature. Second, using the newly developed theoretical basis, this study shows that the choice of time horizon in the GWP can be directly related to the choice of discount rate or other fundamental economic parameters. Finally, using a numerical formulation that includes an up-to-date representation of state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks, this study shows that there is generally strong agreement between the theoretical and numerical approaches across a reasonable range of assumptions for both economic and climate system parameters.

The theoretical treatment developed here can be used to develop a simple “heuristic” to relate the GWP time horizon to the discount rate. Using Eq. 14, if the economic growth rate were ~ 2% per year, a TH of 100 years would be consistent with a 3% discount rate, whereas a TH of 20 years would be consistent with a 7% discount rate. Alternatively, using Eq. 15, the TH in the GWP can be related to the pure rate of time preference (ρ) and coefficient of relative risk aversion (η). Assuming an economic growth rate of ~ 2% per year, a time horizon of 100 years would be consistent with a pure rate of time preference of 1% and a coefficient of relative risk aversion equal to 1. On the other hand, a time horizon of 20 years would be consistent with a pure rate of time preference of 1% only if the coefficient of relative risk aversion was near 3, and a coefficient less than 2 would be consistent only if the pure rate of time preference was above 3%. Figure S 8 shows contours of constant TH for different choices of ρ and η. Generally, these results suggest that lower values for both the pure rate of time preference and the coefficient of relative risk aversion lead to lower values for the resulting discount rate and therefore higher values for TH. However, it should be noted that these results do not consider the effects of uncertainty, which can lead to a more complex dependence on η (Anthoff et al. 2009).

Although this study provides a basis for relating choices made about the GWP to choices about parameters commonly used in economic analysis, it does not provide guidance about the choice of discount rate itself. However, this choice is a well-studied problem in economics, and it remains an area of active inquiry (The National Academies 2017). Several different approaches have suggested that values for the discount rate close to the consumption rate of interest are appropriate for valuation of long-term climate change impacts. For example, it has been shown that uncertainty about discount rates in the far future leads to lower certainty-equivalent rates (Newell and Pizer 2003; Arrow et al. 2014). More recently, it has been shown that uncertainty about whether impacts in the far future affect capital investment or household consumption leads to rates that converge toward the consumption rate (Li and Pizer 2018). It should be noted that even if the consumption rate of interest is deemed to be the appropriate rate, the actual value for that rate remains inherently uncertain (Drupp et al. 2018). Nonetheless, given these considerations, it is not surprising that in the context of the GWP, others have noted that “…the 100-year timescale is consistent with discount rates that are commonly used for climate change analysis” (Sarofim and Giordano 2018).

Beyond the insights provided by the new theoretical framework, the numerical results lead to several additional conclusions. First, the cases examined in Sect. 3 suggest that the theoretical result can be replicated under the simplest set of assumptions. Second, the theory correctly anticipates the insensitivity of results to certain choices, such as equilibrium climate sensitivity and methane lifetime. Third, the numerical results help to quantify and explain the state-dependence of the relationship, which cannot be examined easily using the theoretical formulation alone. The most important form of state-dependence is the dependence on climate background state (i.e., RCP) when climate-carbon cycle feedbacks are turned on. Fourth, the numerical results help to quantify the sensitivity of the fit to alternative economic growth and damage function assumptions.

The agreement between theory and numerical results is most sensitive to these latter two assumptions, namely the representation of economic growth and climate damages. Generally, the fit worsens if the economic growth rate is itself time-dependent, or if the damage function changes from a moderately convex (quadratic) shape toward one that is either more strongly convex or more nearly linear. However, neither of these assumptions is well constrained. Future economic growth is quite uncertain, so it is challenging to determine which assumptions about the economic growth rate are most plausible (Dellink et al. 2017). Similarly, the damage representation is a major uncertainty in climate change economics (The National Academies 2017).

In summary, the theoretical framework described here has been extensively evaluated using numerical experiments. Taken together, the theoretical and numerical results further clarify that the choice of time horizon in the GWP is fundamentally a choice about how to aggregate impacts that occur over time. That is, it is a choice about economic time preference that is tantamount to the choice of discount rate. While the choice of discount rate is inherently subjective, it is a well-studied problem in economics, and as such, can be informed by various strands of normative and empirical analysis, knowledge of the application, and consistency with other practices (The National Academies 2017).

These considerations do not conflict with recommendations to perform sensitivity analysis using different climate metrics in the context of technology assessment and climate policy analysis, but they do suggest that certain variants of some metrics may be more or less appropriate to consider in such analysis. The GWP is most consistent with a cost-benefit framework than with a cost-effectiveness framework (Tol et al. 2012; Mallapragada and Mignone 2017). Nonetheless, many analyses of climate mitigation policies, including those aimed at climate stabilization, rely on the GWP to apply carbon prices to other GHGs (Smith et al. 2013; Tanaka and O’Neill 2018), and the findings of this study can inform that translation. Given the importance of climate metrics to policy analysis (Smith et al. 2013; Tanaka and O’Neill 2018; Allen et al. 2018) and technology assessment (Edwards and Trancik 2014; Levasseur et al. 2016; Mallapragada and Mignone 2017), practitioners using climate metrics such as the GWP may wish to consider how choices about TH align with choices about discount rates used in the valuation of long-term climate change impacts.

Change history

09 December 2019

The original article has been corrected. The figures in this article were updated.

Notes

Both the GWP and GDP will be defined mathematically in the next section.

We assume an infinite upper bound in the theoretical expression for the social cost for mathematical simplicity. In practice, the upper bound is usually truncated several hundred years into the future (e.g., the DICE model uses a 500-year integration horizon (Nordhaus 2017)). Assuming that the integral converges, the approximation introduced here is unlikely to introduce large error for most parameter choices.

Temperatures vary over time when concentrations are fixed until the system reaches a new equilibrium. However, this exception introduces only minor error into the approximation.

References

Allen MR, Shine KP, Fuglestvedt JS et al (2018) A solution to the misrepresentations of CO2-equivalent emissions of short-lived climate pollutants under ambitious mitigation. NPJ Clim Atmos Sci 1:16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-018-0026-8

Anthoff D, Tol RSJ, Yohe GW (2009) Risk aversion, time preference, and the social cost of carbon. Environ Res Lett 4:024002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/4/2/024002

Arrow KJ, Cropper ML, Gollier C et al (2014) Should governments use a declining discount rate in project analysis? Rev Environ Econ Policy 8:145–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/reu008

Azar C, Johansson DJA (2012) On the relationship between metrics to compare greenhouse gases – the case of IGTP, GWP and SGTP. Earth Syst Dyn 3:139–147. https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-3-139-2012

Boucher O (2012) Comparison of physically- and economically-based CO2-equivalences for methane. Earth Syst Dyn 3:49–61. https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-3-49-2012

Cherubini F, Tanaka K (2016) Amending the inadequacy of a single indicator for climate impact analyses. Environ Sci Technol 50:12530–12531. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b05343

Cherubini F, Fuglestvedt J, Gasser T et al (2016) Bridging the gap between impact assessment methods and climate science. Environ Sci Pol 64:129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVSCI.2016.06.019

Collins WJ, Fry MM, Yu H et al (2013) Global and regional temperature-change potentials for near-term climate forcers. Atmos Chem Phys 13:2471–2485. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-2471-2013

Dellink R, Chateau J, Lanzi E, Magné B (2017) Long-term economic growth projections in the shared socioeconomic pathways. Glob Environ Chang 42:200–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2015.06.004

Drupp MA, Freeman MC, Groom B, Nesje F (2018) Discounting disentangled. Am Econ J Econ Policy 10:109–134. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20160240

Edwards MR, Trancik JE (2014) Climate impacts of energy technologies depend on emissions timing. Nat Clim Chang 4:347–352. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2204

Etminan M, Myhre G, Highwood EJ, Shine KP (2016) Radiative forcing of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide: a significant revision of the methane radiative forcing. Geophys Res Lett 43:12,614–12,623. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL071930

Fankhauser S (1994) The social costs of greenhouse gas emissions: an expected value approach. Energy J 15:157–184

Fricko O, Havlik P, Rogelj J et al (2017) The marker quantification of the shared socioeconomic pathway 2: a middle-of-the-road scenario for the 21st century. Glob Environ Chang 42:251–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2016.06.004

Fuglestvedt JS, Berntsen TK, Godal O et al (2003) Metrics of climate change: assessing radiative forcing and emission indices. Clim Chang 58:267–331. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023905326842

Gasser T, Peters GP, Fuglestvedt JS et al (2017) Accounting for the climate–carbon feedback in emission metrics. Earth Syst Dyn 8:235–253. https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-8-235-2017

Gillett NP, Matthews HD (2010) Accounting for carbon cycle feedbacks in a comparison of the global warming effects of greenhouse gases. Environ Res Lett 5:034011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/5/3/034011

Hammitt JK, Jain AK, Adams JL, Wuebbles DJ (1996) A welfare-based index for assessing environmental effects of greenhouse-gas emissions. Nature 381:301–303. https://doi.org/10.1038/381301a0

International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis (2009) RCP Database (version 2.0.5). In: IIASA. http://www.iiasa.ac.at/web-apps/tnt/RcpDb. Accessed 13 May 2018

International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis (2016) SSP Scenario Database. https://secure.iiasa.ac.at/web-apps/ene/SspDb/dsd?Action=htmlpage&page=about. Accessed 7 Jun 2018

Joos F, Roth R, Fuglestvedt JS et al (2013) Carbon dioxide and climate impulse response functions for the computation of greenhouse gas metrics: a multi-model analysis. Atmos Chem Phys 13:2793–2825. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-2793-2013

Kandlikar M (1995) The relative role of trace gas emissions in greenhouse abatement policies. Energy Policy 23:879–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-4215(95)00108-U

Kopp RE, Mignone BK (2013) Circumspection, reciprocity, and optimal carbon prices. Clim Chang 120:831–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0858-5

Lashof DA, Ahuja DR (1990) Relative contributions of greenhouse gas emissions to global warming. Nature 344:529–531. https://doi.org/10.1038/344529a0

Levasseur A, Cavalett O, Fuglestvedt JS et al (2016) Enhancing life cycle impact assessment from climate science: review of recent findings and recommendations for application to LCA. Ecol Indic 71:163–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOLIND.2016.06.049

Li Q, Pizer WA (2018) Discounting for public cost-benefit analysis. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, Vol. No. 25413. http://www.nber.org/papers/w25413.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2019

Mallapragada D, Mignone BK (2017) A consistent conceptual framework for applying climate metrics in technology life cycle assessment. Environ Res Lett 12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7397

Marten AL, Newbold SC (2012) Estimating the social cost of non-CO2 GHG emissions: methane and nitrous oxide. Energy Policy 51:957–972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.09.073

Meinshausen M, Smith SJ, Calvin K et al (2011) The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions from 1765 to 2300. Clim Chang 109:213–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0156-z

Millar JR, Nicholls ZR, Friedlingstein P, Allen MR (2017) A modified impulse-response representation of the global near-surface air temperature and atmospheric concentration response to carbon dioxide emissions. Atmos Chem Phys 17:7213–7228. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-7213-2017

Myhre G, Highwood EJ, Shine KP, Stordal F (1998) New estimates of radiative forcing due to well mixed greenhouse gases. Geophys Res Lett 25:2715–2718. https://doi.org/10.1029/98GL01908

Myhre G, Shindell D, Bréon F-M et al (2013a) Anthropogenic and natural radiative forcing. In: Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner G-K et al (eds) Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Myhre G, Shindell D, Bréon F-MF-M, et al. (2013b) Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing Supplementary Material. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)].

Newell RG, Pizer WA (2003) Discounting the distant future: how much do uncertain rates increase valuations? J Environ Econ Manage 46:52–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0095-0696(02)00031-1

Nordhaus WD (2017) Revisiting the social cost of carbon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:1518–1523. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1609244114

Ocko IB, Hamburg SP, Jacob DJ et al (2017) Unmask temporal trade-offs in climate policy debates. Science (80- ) 356:492 LP–492493

Peters GP, Aamaas B, Berntsen T, Fuglestvedt JS (2011) The integrated global temperature change potential (iGTP) and relationships between emission metrics. Environ Res Lett 6:044021. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/6/4/044021

Ramsey FP (1928) A mathematical theory of saving. Econ J 38:543. https://doi.org/10.2307/2224098

Sarofim MC, Giordano MR (2018) A quantitative approach to evaluating the GWP timescale through implicit discount rates. Earth Syst Dyn Discuss 9:1013–1024

Shine KP, Fuglestvedt JS, Hailemariam K, Stuber N (2005) Alternatives to the global warming potential for comparing climate impacts of emissions of greenhouse gases. Clim Chang 68:281–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-005-1146-9

Shine KP, Berntsen TK, Fuglestvedt JS, ComShine KP, Berntsen TK, Fuglestvedt JS, Skeie RB, Stuber N (2007) Comparing the climate effect of emissions of short- and long-lived climate agents. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engin. Philos Trans R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci 365:1903–1914. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2007.2050

Smith SJ, Karas J, Edmonds J et al (2013) Sensitivity of multi-gas climate policy to emission metrics. Clim Chang 117:663–675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-012-0565-7

Smith CJ, Forster PM, Allen M et al (2018) FAIR v1.3: a simple emissions-based impulse response and carbon cycle model. Geosci Model Dev 11:2273–2297. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-2273-2018

Tanaka K, O’Neill BC (2018) The Paris agreement zero-emissions goal is not always consistent with the 1.5 °C and 2 °C temperature targets. Nat Clim Chang 8:319–324. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0097-x

Tanaka K, Peters GP, Fuglestvedt JS (2010) Policy update: multicomponent climate policy: why do emission metrics matter? Carbon Manag 1:191–197. https://doi.org/10.4155/cmt.10.28

Tanaka K, Johansson DJA, O’Neill BC, Fuglestvedt JS (2013) Emission metrics under the 2 °C climate stabilization target. Clim Chang 117:933–941. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0693-8

The National Academies (2017) Valuing climate damages: updating estimation of the social cost of carbon dioxide. Washington, DC

Tol RSJ, Berntsen TK, O’Neill BC et al (2012) A unifying framework for metrics for aggregating the climate effect of different emissions. Environ Res Lett 7:044006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/7/4/044006

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 1098 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mallapragada, D.S., Mignone, B.K. A theoretical basis for the equivalence between physical and economic climate metrics and implications for the choice of Global Warming Potential time horizon. Climatic Change 158, 107–124 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02486-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02486-7