Abstract

Child welfare work is inherently difficult, and child welfare agencies are known to experience high rates of turnover. We sought to expand the existing literature on intention to leave one’s child welfare agency and commitment to child welfare work through examining the coping mechanisms of frontline workers. Having and utilizing healthy coping mechanisms has proved beneficial to child welfare workers in previous research. In this paper, we examine specific coping mechanisms identified in the Comprehensive Organizational Health Assessment and how they were associated with child welfare workers’ intent to leave their agency and their commitment to remain in the field of child welfare during the SARS CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. We surveyed over 250 child welfare caseworkers using the COHA instrument. Using both bivariate analysis and linear regression, we identify specific coping mechanisms, such as staying present with friends and family, as highly influential and discuss ways to strengthen these areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

For decades, high turnover has remained a significant challenge in the child welfare field (Madden et al., 2014). Turnover rates in the United States over the last two decades have ranged between 20% and 40% each year (Rittschof & Fortunato, 2015; Westbrook et al., 2006) with some studies reporting even higher rates (Drake & Yadama, 1996; Salloum et al., 2015). Rapid turnover can have deleterious impacts on caseworkers, the child welfare agencies where they work, and the children and families they serve. When caseworkers leave their positions, agencies must not only recruit and retrain new workers but also address the change in morale and productivity among remaining workers that can result (Gomez et al., 2010). Transitions between caseworkers may also cause disruptions or delays in services that can negatively impact children and families involved in the system (Fulcher & Smith, 2010). More specifically, research shows that children who experience multiple reassignments experience extended time to permanency and reduced likelihood of reunification (Flower et al., 2005; Strolin-Goltzman et al., 2010). Given these far-reaching impacts, understanding turnover—and the factors that both contribute to and protect against it—is important in creating more stability in the field and better outcomes for children and families.

The work of child welfare caseworkers is, in many ways, uniquely stressful and challenging (Genç & Buz, 2020). Front-line workers are often exposed to trauma and stress in their day-to-day work and, as a result, may experience emotional exhaustion and burnout (Leake et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2017; Stalker et al., 2007; Travis et al., 2016). Despite this, some child welfare workers are able to manage and sustain this challenging work over time. In a study of child welfare employees across the United States, Westbrook et al. (2006) found that a combination of individual and organizational factors contributes to turnover and retention. In the study, child welfare workers identified organizational factors such as the ability to take time off, consistent supervision and managerial support, adequate preparation and training for the job, as key to “survival” in the field (Westbrook et al., 2006). At the individual level, personal characteristics, such as strong time management skills, confidence in one’s abilities, and a sense of personal commitment, were seen as supporting retention (Westbrook et al., 2006).

Coping Among Child Welfare Workers

Coping is an important individual-level factor that may contribute to workers’ intent or willingness to remain in their roles and at their agencies (Acker, 2010; Lee et al., 2011). Coping strategies can be understood as the different processes by which individuals respond to and manage stressors (Rienks, 2020). Although there are several ways to define and categorize coping strategies, there are a few dichotomous classifications that are commonly used (Lee et al., 2011). One such classification is approach (active or engaged) versus avoidant (disengaged) coping (Anderson, 2020; Lee et al., 2011; Rienks, 2020). Approach coping strategies address the stressor while avoidant coping strategies avoid or distract from the stressor (Anderson, 2000; Koeske et al., 1993). A second common classification is emotion-focused versus problem-focused coping. Emotion-focused strategies target the emotions associated with or produced by the problem or stressor, and problem-focused strategies address the problem itself (Genç & Buz, 2020). Finally, some studies classify strategies as either negative or positive depending on their effectiveness (Lamothe et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2017).

A growing body of literature explores how child welfare workers cope with the demands of their jobs. More specifically, this research considers which types of coping strategies are most effective in reducing factors that have been linked to turnover, such as emotional exhaustion, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout (Anderson, 2000; Rienks, 2020; Salloum et al., 2015; Stalker et al., 2007). A number of studies have indicated that active coping strategies are particularly effective in buffering against stress, burnout, and turnover intentions (Koeske et al., 1993; Lee et al., 2011). Anderson (2000) examined child protective service workers’ use of both engaged coping strategies (similar to active coping strategies) and disengaged coping strategies (similar to avoidant strategies). Engaged coping strategies included behaviors such as problem-solving and emotional expression, while disengaged coping strategies included problem-avoidance and social withdrawal. In this study, engaged coping strategies were associated with an increased sense of personal accomplishment and decreased feelings of personalization. By contrast, disengaged coping strategies were associated with reduced sense of personal accomplishment and increased depersonalization. Of note, neither engaged nor disengaged coping strategies led to a decrease in emotional exhaustion (Anderson, 2000).

Emotion-focused coping strategies may also be particularly effective in reducing stress and tension among child welfare workers (Anderson, 2000; Genç & Buz, 2020). Workers in Anderson’s (2000) previously referenced study used social support, an emotion-focused coping strategy, to a lesser extent than other active coping strategies; however, research indicates that interpersonal support could be particularly effective in buffering against emotional exhaustion and burnout (Anderson, 2000; Newell & MacNeil, 2010). In a study of child welfare workers in Turkey, Genç and Buz (2020) found that, while workers used both emotion- and problem-focused coping methods, emotion-focused coping strategies were more effective in enhancing workers’ resilience. Humor is another coping strategy that can be conceptualized as an emotion-focused coping strategy, especially when it is used to lessen negative emotions or tension (Abel, 2002). In focus group interviews, Westbrook et al. (2006) found that public child welfare workers cited humor as helping to reduce stress and feelings of anxiety, fear, and anger. What’s more, humor was viewed as “an expression of camaraderie” (Westbrook et al., 2006, p. 51) among colleagues.

Coping and Trauma

The potential impact of trauma on child welfare workers is a critical consideration when exploring turnover intentions. In a study examining how caseworkers’ coping strategies impacted their levels of secondary traumatic stress (STS), Rienks (2020) found that those workers who were more likely to use coping strategies experienced lower levels of STS, both at the time of the study and three years later, than their counterparts who used fewer. In addition, the workers with developed self-care plans that utilized active coping strategies reported lower levels of STS than those without such plans (Rienks, 2020). Other research in this area suggests that particularly effective self-care plans address both the physical and emotional well-being of the individual through strategies such as exercise, good nutrition, art making, and leaning on one’s social network for support (Hesse, 2002; Newell & MacNeil, 2010). Salloum et al. (2015) found that the use of trauma-informed self-care strategies, which consider and address the impact of trauma on workers and clients alike, were linked to reduced burnout and increased compassion satisfaction (though not associated with changes in secondary trauma).

As Westbrook et al. (2006) highlight, organizational factors and personal factors together contribute to workers’ experiences and, ultimately, their turnover intentions (Stalker et al., 2007; Westbrook, 2006). In this vein, Lee et al. (2011) argue that the culture of an organization can be conceptualized as a coping resource, in that organizational factors such as supervision and support can enable workers’ to use coping strategies that ultimately enhance their experience and improve retention. In other words, while workers’ coping strategies, such as control coping, can be effective in reducing turnover intentions, it is critical that the organization environments in which they operate support and even facilitate their use (Lee et al., 2011).

Emerging research indicates that the SARS CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic has had an impact on the child welfare workforce (Miller et al., 2020). In one study, child welfare workers were found to be above the normal level of distress in relation to COVID-19 (Miller et al., 2020). In another study, the impact of having to move training for child welfare workers on-line was examined (Schwab-Reese et al., 2020) and found that training was still effective. COVID-19 had a strong impact on the delivery of child welfare services and likely had a direct impact on the coping strategies and turnover of the child welfare workforce. In many cases, quarantines and lockdowns exacerbated youth risk for parental maltreatment (Wong et al., 2020) while also exacerbating personal stress and hardship in the lives of those delivering frontline child welfare services (Williams, 2021). Some of the coping mechanisms historically used by those child welfare service providers to combat stress and trauma may have been unavailable at that time (especially those including in-person interaction with social relations, such as attending religious services in a church or attending a workout class at a gym). Female-identified frontline workers of color may have been particularly burdened as they navigated long-standing systematic inequities in the domains of healthcare, housing, employment, and childcare (Adams et al., 2021).

In this study, we first examine the coping mechanisms used amongst a group of child welfare workers using the comprehensive behavioral health assessment (COHA) in late 2020. We then look at the association between those coping mechanisms and intent to leave one’s child welfare agency and commitment to the field of child welfare. Our purpose was to examine the relationship between specific coping mechanisms and caseworkers’ commitment to child welfare and at their intent to leave their current agency.

Method

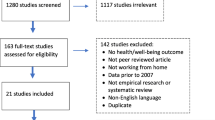

Data Collection and Sample

The survey was sent to 394 frontline child welfare staff members employed by a child welfare agency located in a large Northeastern city in the United States. Two hundred and fifty-eight participants responded to at least part of the survey, representing about a 65% response rate. Participants were employed by this agency between October and November of 2020 when the study took place. The private agency where these participants were employed is one of the largest providers of foster care and child welfare preventive services in the city.

A small team of high-level administrative representatives at this agency identified job titles and roles that they wished to include in this study, limiting these roles to employees providing direct services to child welfare involved children and families (most commonly child welfare case workers and child welfare supervisors; see below findings). Employees with these titles received an email with a link to a Qualtrics survey in October 2020 and were given four weeks to complete the survey. This email and subsequent reminder emails were sent by an agency representative in an effort to further protect the confidentiality of potential participants. The members of the research team did not have access to these email addresses unless they were provided by participants for compensation purposes at the end of the survey. The administrative representatives were not part of the formal research team; they had no access to the Qualtrics survey data and were not able to determine which employees took the survey and which did not. Potential participants were told on multiple occasions that their participation was entirely voluntary and that the study was being completed by an external, university-based research team. It was clearly conveyed that this meant that those working at their agency would not know whether they took the survey, and that their participation in the study had no bearing on their employment status.

Upon completing the survey, each participant was eligible for a $20 gift card to Amazon (sent to the email address that they chose to provide at the end of the survey). The survey was not linked with the gift card interface, so there was no way for the research team to link survey answers with specific email addresses. The survey took, on average, approximately 20 min to complete. Before this study took place, similar studies using the same protocol were completed at three other private child welfare agencies in the same large Northeastern city between September 2018 and January 2019.

For the purposes of this study, we only use data from the fourth child welfare agency included in this study, as this survey was the only one completed by employees during the COVID-19 pandemic. We believe the experience of navigating child welfare work responsibilities in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic would uniquely influence participant views on (a) coping and (b) intent to leave their jobs, their places of employment and the field of child welfare in general so we sought to explore these relationships in the fourth data set only. Further details on a study including the first three child welfare agencies can be found in a paper recently published by the research team (Katz et al., 2021).

Compliance with Ethical Standards. The study protocol for use of the survey at each agency was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB), for human subjects research, of the primary investigator’s university. There were no conflicts of interest. Informed consent was achieved through a consent form at the beginning of each survey, participants had to agree to participate in the survey prior to selecting the link to open the full survey.

Comprehensive Organizational Health Assessment (COHA)

The COHA was created through a grant-funded project using an iterative process, testing the measure at different stages, to develop a measurement that examined organizational health specifically within child welfare agencies (Potter et al., 2015). The survey was created by the above-mentioned research team (Potter and colleagues) and is available for non-proprietary use by child welfare workforce researchers through developing an agreement with the original research team. The COHA has been tested and found to be reliable (Rienks, 2020).

For this study, an abbreviated version of the COHA was co-created by the research team and administrative agency representatives from each of the four participating agencies. Although the original version of the COHA includes 20 subscales, this abbreviated version includes only 10 in an effort to minimize the burden placed on potential participants at each partnering agency. The included subscales were intent to leave, coping strategies, job satisfaction, leadership, peer support, secondary traumatic stress, burnout, supervision quality and frequency, supervision for frontline staff, supervision for supervisors, and one general open-ended question. These subscales were chosen because they felt most important and relevant to agency administrators.

Coping Strategies

The original COHA assesses 15 types of coping mechanisms, and participants can include a qualitative response when asked if they have others not mentioned. At the request of the agencies, we also included a 16th mechanism: alcohol use. Participants were asked to respond to how often they use each particular coping mechanism, from items such as practicing physical self-care to debriefing with colleagues; 1 indicated almost never, and 5 indicated almost always. All mechanisms are listed below (see Table 1).

Intent to Leave

The COHA includes six questions that ask about intent to leave the child welfare agency and seven questions that ask about intent to remain working within the field of child welfare. Participants are able to rank the primary reasons they choose to stay in their jobs. Participants are also asked questions about how many more years they expect to work at their agency, how many jobs they have applied for, and how often they conduct job searches. We chose to use the specific questions, as described below, of intent to leave the agency and commitment to the field of child welfare in our analyses.

Results

Demographics

Most participants indicated that they were “case planners” (n = 70; 27.2%), while the second highest number of participants indicated they were “supervisors” (n = 56; 21.8%). About 55% of participants had been in their position for one year or less than one year (n = 140; 54.7%). Participants reported a longer period of time working in child welfare, with the mode being 3 years (see Table 2). Almost all participants (n = 230, 89.5%) indicated that they worked directly with children and families. Participants reported that, on average, they worked with about 9 families (M = 9.53[9.16]) and about 11 children (M = 11.19[10.90]).

Almost 70% of participants indicated that child welfare was not their first choice when they began planning their career (n = 162, 69.5%). For 65.7% of participants, their current position was their first full-time job in child welfare (n = 153). When asked if participants could turn back the clock and revisit their decision to take their current position, most indicated they would make the same decision (n = 171; 74%).

The vast majority of participants reported that they identified as female (n = 211; 90.9%). The age range was 21 years to 66 years and older, with the mode being 27 and 28 years and the median age being 40 years old. Table 3 depicts the race/ethnicity of the sample. Participants were able to write in a response if the categories did not match their race/ethnicity; these are shown in the notes below Table 3. Most participants reported that they did not have children (n = 156; 67%) or elder care responsibility (n = 157; 67.4%) at the time of the survey. Twenty-six percent indicated that they were married (n = 60), while most reported that they had never married (n = 149; 64.5%).

When asked if they held a social work degree, 101 participants indicated that they did (43.3%) while 132 indicated they did not (56.7%). Of those that held a Social Work degree, 88 participants stated they had a Master of Social Work, and 14 had a Bachelor of Social Work. Almost 10% of participants stated they were working on their Master of Social Work (n = 22; 9.6%). When examining annual salary, the highest percentage of participants stated that they made between $55,001 and $60,000 annually (n = 70; 30.2%). Most participants reported an annual income between $40,001 and $60,000.

Descriptive Statistics

Coping

We found that those coping skills used most often were: relying on a diverse network outside of work for social support (M = 3.56); feeling supported by a supervisor in the participant’s self-care plan (M = 3.54); using humor as a coping tool (M = 3.68); staying present with friends or family (M = 3.73); practicing physical self-care (M = 3.53); and being mindful of vicarious trauma (M = 3.54). We found that working to stay present with friends and family had the highest mean score, demonstrating that participants indicated that they used this coping skill to cope about half of the time to usually.

Participants were able to write in an “other” coping mechanism. We received 152 open-ended responses. Some examples of these statements were: “Baking/Cooking; Spending time with loved ones; Listening to uplifting music; Traveling and camping; Reading a book; Arts/crafts; Exercise/going to the gym/running/cardio; Watching TV; and Mindfulness.”

Intent to Leave

As mentioned in the Method section, participants were asked to rate their plan to leave the agency as soon as possible from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree (i.e., a lower mean score indicates a higher intention to stay). Overall, the participants reported a mean score of 2.40(0.95). Table 4 shows the breakdown of responses, with disagree being the most common response (n = 98; 43.4%).

Looking at commitment to working in child welfare, participants were asked, on the same scale, how much they agreed or disagreed with the statement “I am committed to work in child welfare.” On average, participants reported a mean score of 3.24(1.03). Table 5 displays the breakdown of the scores. For this item, we see that highest percentage of participants were neutral, neither agreeing nor disagreeing (n = 89; 39.2%), with 30.4% agreeing that they are committed to working in child welfare (n = 69).

Bivariate Analysis

We wanted to examine the relationships between coping mechanisms and intent to leave the agency and commitment to stay in the field of child welfare to identify those significant relationships. First, looking at intent to leave the agency, we found weak yet significant relationships with the coping skills listed in Table 6. The following coping mechanisms indicated the strongest relationships: support available through the child welfare agency (r = −0.24; p ≤ 0.01); discussing the self-care with a supervisor (r = −0.24; p ≤ 0.01); feeling supported by a supervisor in the self-care plan (r = −0.26; p ≤ 0.01); staying present with friends or family (r = −0.23; p ≤ 0.01); and practicing religious or spiritual renewal (r = −0.26; p ≤ 0.01).

Second, we examined the bivariate relationship between commitment to child welfare and coping mechanisms. Again, we found weak yet significant relationships with specific coping skills. These coping skills were: being mindful of exposure to vicarious trauma (r = 0.23; p ≤ 0.01); having a work-to-home transition plan (r = 0.13; p ≤ 0.05); staying present with friends or family (r = 0.13; p ≤ 0.05); paying attention to physical responses when exposed to trauma situations (r = 0.13; p ≤ 0.05); and practicing religious or spiritual renewal (r = 0.17; p ≤ 0.01).

We found four coping skills that had a relationship with both intent to leave the agency and commitment to the field of child welfare: (1) practicing physical self-care; (2) having a work-to-home transition plan; (3) staying present with friends or family; and (4) practicing religious or spiritual renewal.

Linear Regression

In an effort to further understand the relationship between coping mechanisms and both one’s intent to leave the agency and their commitment to the agency, we conducted two separate linear regressions, due to the continuous nature of the variables, using the coping mechanisms that were found to have significant bivariate relationships with both dependent variables. Because of the high number of variables in the coping scale, and a concern for power with the sample size, we limited the number of variables we included, choosing only those with significant bivariate relationships. We did not include demographic variables such as years in the agency as the data was skewed. With intent to leave the agency, we found that the model was significant, F(4, 213) = 5.92; p ≤ 0.01, and explained 10% of the variance (R2 = 0.10). The linear regression showed a significant, negative relationship between the two predictor variables, indicating that as participants scores on the coping skills increased, their plans to leave the agency decreased (signifying a higher likelihood of staying). These two significant relationships were: staying present with friends and family (β = −0.18; p ≤ 0.05); and practicing religious or spiritual renewal (β = −0.17; p ≤ 0.02). Table 7 displays the regression findings for this model. In conducting the second regression analysis, we found no significant associations between commitment to the field of child welfare and the identified 4 coping mechanisms. Although the model was significant (F(4, 214) = 2.56; p ≤ 0.05), it only explained about 5% of the variance (R2 = 0.05).

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, we want to highlight that this survey was conducted during the time of COVID-19. This might have impacted participants’ responses relating to coping and intent to leave. For example, accessing physical self-care such as going to the gym may have been more difficult during this time. There is also the potential that this time exacerbated stress for participants, thus impacting their ability to cope and/or use the identified coping mechanisms. We did see in the open-ended responses that COVID-19 was a factor in several responses. For example, one participant wrote “Due to COVID-19, life has altered for everyone in so many ways,” and another stated “case planners did not agree to put their lives on the front line of COVID when they agreed to be case planners.”

The study also is limited in its generalizability as it was conducted in one child welfare agency in one state. Due to the use of a cross-sectional approach, we cannot determine causality from this study. There are also limitations regarding selection bias as it could be that only a specific selection of staff participated in the study. Lastly, in order to prioritize the anonymity of study participants, we used a survey link that was not connected to participants’ IP addresses. This meant that it was possible for those who received the survey to take it more than once. While this occurrence was exceedingly rare, we know that a small number of participants (<6) took the survey twice when they weren’t sure if their first responses were logged. We evaluated each survey entry in an effort to delete duplicate entries. Despite these limitations, we believe the study has meaningful and important findings.

Discussion

Child welfare work is characteristically difficult, and child welfare agencies experience high rates of turnover (Westbrook et al., 2006). These agencies, as well as child welfare researchers, consistently look to find ways to retain child welfare staff. In a previous article (Katz et al., 2021), we found a relationship between agency leadership and intent to leave in three child welfare agencies in a large Northeastern city. Other research has examined factors related to retention and burnout such as organizational and personal factors (Westbrook et al., 2006), job satisfaction (Stalker et al., 2007), and professional organizational culture and coping strategies (Lee et al., 2011). Previous research has explored the coping mechanisms of child welfare staff, and the use of effective coping mechanisms has been identified as valuable in child welfare work (Anderson, 2000; Lee et al., 2011; Rienks, 2020).

In this study, we wanted to identify which coping skills might have a relationship with a child welfare worker having decreased intention to leave their agency and an increased commitment to child welfare during the COVID 19 pandemic. In our descriptive analyses, we found that a variety of coping mechanisms are used by child welfare staff—16 specific mechanisms and a lengthy list of “other” skills. Of these mechanisms, we found that staying present with friends or family was the most commonly used coping skill. We also found staying present with friends and family to have a significant bivariate relationship with both of our dependent variables, intent to leave the agency, and commitment to the field of child welfare. In addition to staying present with friends and family, practicing physical self-care, having a work-to-home transition plan, and practicing religious or spiritual renewal were also coping mechanisms that were significantly associated with the dependent variables.

When examining intent to leave, child welfare agencies may want to help their workers assess the extent to which they are engaging in these (and other) active coping strategies, and potentially provide opportunities for these and other meaningful strategies to be further developed or cultivated during work hours. This can occur in in-person or online individual and group supervision as well as modeling and training. Child welfare agencies can create time and space for staff to practice physical self-care, to have a concrete work-to-home transition plan, to stay present with friends or family, and to practice religious or spiritual renewal (however that might look for them). Self-care for child welfare workers has been explored in the literature, examining such concepts as physical activity and outlining the importance of agency and professional support for caseworkers to be able to access self-care mechanisms (Miller et al., 2018). Additionally, Salloum et al. (2019) found that stress-management and having a work-life balance plan mediated the relationship between burnout, secondary trauma and the level of mental health functioning. Given the traumatic stress that has been placed on many frontline caseworkers as they navigate COVID-19, these coping mechanisms may be more important now than they have been in the past.

Next, we found that participants who reported higher scores on staying present with family and friends had lower scores on intent to leave the agency (p ≤ 0.05). The same was found for practicing religious or spiritual renewal (p ≤ 0.02). Although we don’t know the specifics of either of these acts (e.g., how participants interpreted “staying present” or “spiritual renewal,” for example), these findings carry important messages for those looking to effectively support frontline workers. Endorsement of the first coping mechanism, staying present with friends and family, may be an especially potent protective factor because it is undergirded by the basic assumption that the participant has the ability to access a network of friends and family members. The importance of social support as a buffering factor for secondary traumatic stress, psychiatric illness, and trauma has been well documented in the literature (Galek et al., 2011; MacRitchie & Leibowitz, 2010; Rzeszutek et al., 2015). Beyond the presence of these connections, the wording of this item conveys that the participant and their sources of social support (friends and family) are engaging in substantive exchanges in which all parties “stay present.” This “staying present” may imply that the participant is focused on the social conversations at hand as opposed to being focused on child welfare-specific content, like they might be in supervision at work. The ability to temporarily suspend thinking about work may play an important role in their ability to stay at their jobs in that workers who “stayed present” in social interactions may have the ability to compartmentalize work and personal content. The ability to engage with social connections, and to compartmentalize work content, may be particularly protective in the era of COVID-19, when child welfare staff members may be more isolated from extensive social networks.

Although there is literature on the relationship between social support and turnover in child welfare (Nissly et al., 2005), we did not find literature specific to this concept of staying present and child welfare work. We did find some literature regarding staying present related to mindfulness in relation to affect, indicating that increased mindfulness may lead to decreased negative affect, though not in relation to child welfare work (Polk et al., 2020). This is an area that could potentially benefit from future research.

Endorsement of the second coping mechanism, practicing religious or spiritual renewal, may also speak to the importance of social networks and support, as religious communities have been known to be highly protective in this respect (Assari, 2013; Levin & Chatters, 1998; Merino, 2014). Participants may have benefitted from social gatherings (either in person or virtually) during which they connected with those with whom they shared a world view. Further, a number of studies have shown that religious involvement may be particularly protective for African American women (Harvey et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2016). The importance of this finding in our study may be linked with the fact that African American was the most common race indicated in this study, with 36% of participants identifying as such.

Beyond this, there may be something specifically protective about having a religious or spiritual ideology to call upon when circumstances are particularly stressful. Such ideologies may provide some participants with a compelling reason to do challenging work, and to stick with it when it becomes particularly burdensome. One participant highlighted this in an open-ended response stating, “Our agency encourages self-care and flexibility with schedule, if by chance working overtime or needed. Some of the offices have meditation rooms to encourage workers for breaks or time to pray or meditate.”

Ultimately, child welfare administrators might consider formally allotting some time during weekly supervision (online or in person) to ask their frontline staff members about their chosen coping strategies. Particularly, in the time of COVID-19 it may be even more important for supervisors to help workers find coping strategies that fit their needs and are doable. Supervisors could ask if these staff members have friends and family that they connect with regularly, and if these relationships provide opportunities for non-work-related discussions. If it feels appropriate to do so, they might also inquire about the presence of a faith community, and the protective role this faith (community, ideology) may play in their lives. Asking about these things may be especially important when frontline workers may not be able to physically access their social support networks due to restrictions in place to prevent the spread of COVID- 19. Future research could more closely examine how social support and spirituality impact turnover in the child welfare workforce, leading to a deeper understanding of the mechanisms at work and more specific practice implications.

References

Abel, M. H. (2002). Humor, stress, and coping strategies. Humor, 15(4), 365–381.

Acker, G. M. (2010). How social workers cope with managed care. Administration in Social Work, 34(5), 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/03643107.2010.518125

Adams, G., Ewen, D., & Luetmer, G. (2021). Supporting the child care and early education workforce: A menu of policy options for the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery. Research report. Urban Institute.

Anderson, D. G. (2000). Coping strategies and burnout among veteran child protection workers. Child Abuse and Neglect, 24(6), 839–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00143-5

Assari, S. (2013). Race and ethnicity, religion involvement, church-based social support and subjective health in United States: A case of moderated mediation. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 4(2), 208–217.

Drake, B., & Yadama, G. N. (1996). A structural equation model of burnout and job exit among child protective services workers. Social Work Research, 20(3), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/20.3.179

Flower, C., McDonald, J., & Sumski, M. (2005). Review of turnover in Milwaukee county private agency child welfare ongoing case management staff. Bureau of Milwaukee Child Welfare.

Fulcher, G. M., & Smith, R. J. (2010). Environmental correlates of public child welfare worker turnover. Administration in Social Work, 34(5), 442–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/03643107.2010.518530

Galek, K., Flannelly, K. J., Greene, P. B., & Kudler, T. (2011). Burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and social support. Pastoral Psychology, 60(5), 633–649.

Genç, B., & Buz, S. (2020). Child welfare workers’ resilience and coping styles in Ankara Turkey. International Social Work, 63(5), 597–611.

Gomez, R. J., Travis, D. J., Ayers-Lopez, S., & Schwab, A. J. (2010). In search of innovation: A national qualitative analysis of child welfare recruitment and retention efforts. Children and Youth Services Review, 32, 664–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.01.001

Harvey, I. S., Story, C. R., Knutson, D., & Whitt-Glover, M. C. (2016). Exploring the relationship of religiosity, religious support, and social support among African American women in a physical activity intervention program. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(2), 495–509.

Hesse, A. (2002). Secondary trauma: How working with trauma survivors affects therapists. Clinical Social Work Journal, 30(3), 293–311.

Johnson, S. D., Williams, S. L. L., & Pickard, J. G. (2016). Trauma, religion, and social support among African American women. Social Work and Christianity, 43(1), 60–73.

Katz, C. C., Julien-Chinn, F. J., & Wall, E. (2021). Perceptions of agency leadership and intent to stay: An examination of turnover in the child welfare workforce. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2021.1876808.

Koeske, G. F., Kirk, S. A., & Koeske, R. D. (1993). Coping with job stress: Which strategies work best? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 66, 319–335.

Lamothe, J., Couvrette, A., Lebrun, G., Yale-Soulière, G., Roy, C., Guay, S., & Geoffrion, S. (2018). Violence against child protection workers: A study of workers’ experiences, attributions, and coping strategies. Child Abuse and Neglect, 81, 308–321.

Leake, R., Rienks, S., & Obermann, A. (2017). A deeper look at burnout in the child welfare workforce. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 41(5), 492–502.

Lee, J., Forster, M., & Rehner, T. (2011). The retention of public child welfare workers: The roles of professional organizational culture and coping strategies. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.08.019

Lee, K., Pang, Y. C., Lee, J. A. L., & Melby, J. N. (2017). A study of adverse childhood experiences, coping strategies, work stress, and self-care in the child welfare profession. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 41(4), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2017.1302898

Levin, J. S., & Chatters, L. M. (1998). Religion, health, and psychological well-being in older adults: Findings from three national surveys. Journal of Aging and Health, 10(4), 504–531.

MacRitchie, V., & Leibowitz, S. (2010). Secondary traumatic stress, level of exposure, empathy and social support in trauma workers. South African Journal of Psychology, 40(2), 149–158.

Madden, E. M., Scannapieco, M., & Painter, K. (2014). An examination of retention and length of employment among public child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 41, 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.02.015

Merino, S. M. (2014). Social support and the religious dimensions of close ties. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 53(3), 595–612.

Miller, J. J., Donohue-Dioh, J., Niu, C., & Shalash, N. (2018). Exploring the self-care practices of child welfare workers: A research brief. Children and Youth Services Review, 84, 137–142.

Miller, J. J., Niu, C., & Moody, S. (2020). Child welfare workers and peritraumatic distress: The impact of COVID-19. Children and Youth Services Review, 119, 105508.

Newell, J. M., & MacNeil, G. A. (2010). Professional burnout, vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue: A review of theoretical terms, risk factors, and preventive methods for clinicians and researchers. Best Practices in Mental Health, 6(2), 57–68.

Nissly, J. A., Barak, M. E. M., & Levin, A. (2005). Stress, social support, and workers’ intentions to leave their jobs in public child welfare. Administration in Social Work, 29(1), 79–100.

Polk, M. G., Smith, E. L., Zhang, L. R., & Neupert, S. D. (2020). Thinking ahead and staying in the present: Implications for reactivity to daily stressors. Personality and Individual Differences, 161, 109971.

Rienks, S. L. (2020). An exploration of child welfare caseworkers’ experience of secondary trauma and strategies for coping. Child Abuse and Neglect, 110, 104355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104355

Rittschof, K. R., & Fortunato, V. J. (2015). The influence of transformational leadership and job burnout on child protective services case managers’ commitment and intent to quit. Journal of Social Service Research, 42(3), 372–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2015.1101047

Rzeszutek, M., Partyka, M., & Gołąb, A. (2015). Temperament traits, social support, and secondary traumatic stress disorder symptoms in a sample of trauma therapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 46(4), 213–220.

Salloum, A., Choi, M. J., & Stover, C. S. (2019). Exploratory study on the role of trauma-informed self-care on child welfare workers’ mental health. Children and Youth Services Review, 101, 299–306.

Salloum, A., Kondrat, D. C., Johnco, C., & Olson, K. R. (2015). The role of self-care on compassion satisfaction, burnout and secondary trauma among child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 49, 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.12.023

Schwab-Reese, L. M., Drury, I., Allan, H., & Matz, K. (2020). “Oh, this is actually okay”: Understanding how one state child welfare training system adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110, 104697.

Stalker, C. A., Mandell, D., French, K. M., Harvey, C., & Wright, M. (2007). Child welfare workers who are exhausted yet satisfied with their jobs: How do they do it? Child and Family Social Work, 12, 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00472.x

Strolin-Goltzman, J., Kollar, S., & Trinkle, J. (2010). Listening to the voices of children in foster care: Youths speak out about child welfare workforce turnover and selection. Social Work, 55(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/55.1.47

Travis, D. J., Lizano, E. L., & Mor Barak, M. E. (2016). “I’m so stressed!”: A longitudinal model of stress, burnout and engagement among social workers in child welfare settings. British Journal of Social Work, 46(4), 1076–1095. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct205

Westbrook, T. M., Ellis, J., & Ellett, A. J. (2006). Improving retention among public child welfare workers. Administration in Social Work, 30(4), 37–62. https://doi.org/10.1300/J147v30n04_04

Williams, D. S. (2021). Shared Traumatic Stress and the Impact of COVID-19 on Public Child Welfare Workers. In Shared Trauma, Shared Resilience During a Pandemic (pp. 249–257). Springer, Cham.

Wong, C. A., Ming, D., Maslow, G., & Gifford, E. J. (2020). Mitigating the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic response on at-risk children. Pediatrics, 146(1).

Funding

This study was funded by the agency, to protect confidentiality of the participants we are asking not to name the agency in the funding statement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Informed Consent

This study was approved by Hunter College IRB, and was deferred to Hunter College by University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Julien-Chinn, F.J., Katz, C.C. & Wall, E. An Examination of Coping Strategies and Intent to Leave Child Welfare During the COVID 19 Pandemic. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 40, 587–596 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00800-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00800-w