Abstract

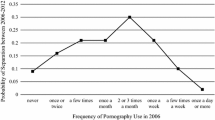

Numerous studies have examined the connection between pornography viewing and marital quality, with findings most often revealing a negative association. Data limitations, however, have precluded establishing directionality with a representative sample. This study is the first to draw on nationally representative, longitudinal data (2006–2012 Portraits of American Life Study) to test whether more frequent pornography use influences marital quality later on and whether this effect is moderated by gender. In general, married persons who more frequently viewed pornography in 2006 reported significantly lower levels of marital quality in 2012, net of controls for earlier marital quality and relevant correlates. Pornography’s effect was not simply a proxy for dissatisfaction with sex life or marital decision-making in 2006. In terms of substantive influence, frequency of pornography use in 2006 was the second strongest predictor of marital quality in 2012. Interaction effects revealed, however, that the negative effect of porn use on marital quality applied to husbands, but not wives. In fact, post-estimation predicted values indicated that wives who viewed pornography more frequently reported higher marital quality than those who viewed it less frequently or not at all. The implications and limitations of this study are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The term “pornography” is both difficult to define and freighted with moral baggage (Lindgren, 1993; Manning, 2006; Short, Black, Smith, Wetterneck, & Wells, 2012). Researchers occasionally elect to use more neutral and descriptive terms like “sexually explicit media or materials,” “erotica,” or “online sexual activity” (Carroll et al., 2008). Yet many studies and national surveys (e.g., General Social Surveys, Portraits of American Life Study, National Study of Youth and Religion, and Baylor Religion Surveys) ask questions about “pornography” attitudes and consumption, and thus I use the term pornography or porn here. For this purposes of this study, pornography will be understood as visual material (magazines, movies, and internet images) intended to sexually arouse the viewer.

Data from the 2014 General Social Survey, for example, suggest that over a third of American men and over 15 percent of women reported viewing an “X-rated movie” in the previous year. Other surveys like the 2006 Portraits of American Life Study indicate that over half of men and over a fifth of women report viewing “pornographic material” in the previous twelve months. Using methods that actually monitored internet users’ online behavior, Edelman (2009) indicates that somewhere over 35 percent of internet users visit an “adult” website at least once a month, and those who visit adult websites once a month average nearly 8 visits per month.

See the limitations acknowledged in Doran and Price (2014, p. 496), Doring (2009, p. 1093), Lambert et al. (2012, p. 419), Maddox et al. (2011, p. 447), Perry (2015, 2016a), Poulsen et al. (2013, p. 81), Stack et al. (2004, p. 86), Stewart and Szymanksi (2012, p. 267), Yucel and Gassanov (2010, p. 731, 736), and Willoughby et al. (2016, p. 157).

Stack et al. (2004), for example, found that a leading predictor of internet porn consumption is an unhappy marriage. Paul (2005) recounted how men who frequently viewed pornography often attributed their use of it to their own sexual frustrations or other relationship problems (see also Olmstead et al., 2013). And Willoughby et al. (2016) recently found significant bi-directional effects between porn use and relationship quality.

Outside of attrition, missing values were either minimal or non-existent for most variables, with the majority of missing values coming from the Wave 2 marital outcome variables (between 11 and 12 % missing values). The independent variables, by comparison, were missing between 0 and 4 %. Because imputing on the dependent variable can risk bias (Allison, 2009), imputation was only done for independent variables with missing information. The MI procedure generated 10 imputation models and then combined them into a single estimation model. The results from all regression models used the MI data. In the end, the results from the MI model estimates were nearly identical to those from regression models I initially ran using listwise deletion.

I also estimated models with these two measures separate and the results were virtually identical in both substantive and statistical significance (results are available upon request).

While I am unable to discern whether pornography use remained stable in participants’ lives between Wave 1 and Wave 2, any observed effect of earlier porn use on later marital quality net of relevant controls would suggest either that porn use at that specific time had a lasting effect on participants’ marital quality or that the trend observed at Wave 1 was indicative of a consistent pattern of porn use in participants’ lives.

Diagnostics for collinearity issues indicated that variance inflation factors (VIFs) and tolerance levels were all well within acceptable ranges. VIFs were all below 1.84 and tolerance levels were all above .55.

Supplementary analyses were run to test for whether the men at more extreme levels of porn use were to blame for the statistically significant effect of porn use on marital quality for men. Results (available upon request) indicated the greatest difference was between those who did not view pornography at all and those who did, rather than between those who viewed pornography at moderate levels and those at more extreme levels.

References

Achen, C. (2000). Why lagged dependent variables can suppress the explanatory power of other independent variables. Paper presented at the meeting of the Political Methodological Section of the American Political Science Association, Los Angeles, CA.

Allison, P. D. (2009). Missing data. In R. E. Millsap & A. Maydeu-Olivares (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of quantitative methods in psychology (pp. 72–89). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Amato, P. R., Johnson, D. R., Booth, A., & Rogers, S. J. (2003). Continuity and change in marital quality between 1980 and 2000. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 1–22.

Attwood, F. (2011). The paradigm shift: Pornography research, sexualization and extreme images. Sociology Compass, 5, 13–22.

Bergner, R. M., & Bridges, A. J. (2002). The significance of heavy pornography involvement for romantic partners: Research and clinical implications. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 28, 193–206.

Bridges, A. J., Bergner, R. M., & Hesson-McInnis, M. (2003). Romantic partner’s use of pornography: Its significance for women. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 29, 1–14.

Bridges, A. J., & Morokoff, P. J. (2011). Sexual media use and relational satisfaction in heterosexual couples. Personal Relationships, 18, 562–585.

Carroll, J. S., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Nelson, L. J., Olson, C. D., McNamara Barry, C., & Madsen, S. D. (2008). Generation XXX: Pornography acceptance and use among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23, 6–30.

Daneback, K., Traeen, B., & Mansson, S. (2009). Use of pornography in a random sample of Norwegian heterosexual couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 746–753.

Doran, K., & Price, J. (2014). Pornography and marriage. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35, 489–498.

Doring, N. M. (2009). The internet’s impact on sexuality: A critical review of 15 years of research. Computers in Human Behavior, 25, 1089–1101.

Edelman, B. (2009). Red light states: Who buys on-line adult entertainment? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23, 209–220.

Ellison, C. G., Henderson, A. K., Glenn, N. D., & Harkrider, K. E. (2011). Sanctification, stress, and marital quality. Family Relations, 60, 404–420.

Emerson, M. O., & Sikkink, D. (2006–2012). Portraits of American Life Study, 2006–2012.

Emerson, M. O., Sikkink, D., & James, A. (2010). The panel study on American religion and ethnicity: Background, methods, and selected results. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 49, 162–171.

Grov, C., Gillespie, B., Royce, T., & Lever, J. (2011). Perceived consequences of casual online sexual activities on heterosexual relationships: A U.S. online survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 429–439.

Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Hook, J. N., & Carlisle, R. D. (2015). Transgression as addiction: Religiosity and moral disapproval as predictors of perceived addiction to pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 125–136.

Johnson, D. (2005). Two-wave panel analysis: Comparing statistical methods for studying the effects of transitions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1061–1075.

Keele, L., & Kelly, N. J. (2006). Dynamic models for dynamic theories: The ins and outs of lagged dependent variables. Political Analysis, 2, 186–205.

Lambert, N. M., Negash, S., Stillman, T. F., Olmstead, S. P., & Fincham, F. D. (2012). A love that doesn’t last: Pornography consumption and weakened commitment to one’s romantic partner. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 31, 410–438.

Lindgren, J. (1993). Defining pornography. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 141, 1153–1275.

Lofgren-Martenson, L., & Mansson, S. (2010). Lust, love, and life: A qualitative study of Swedish adolescents’ perceptions and experiences with pornography. Journal of Sex Research, 47, 568–579.

Maddox, A. M., Rhoades, G. K., & Markman, H. J. (2011). Viewing sexually-explicit materials alone or together: Associations with relationship quality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 441–448.

Mahoney, A. (2010). Religion in families, 1999–2009: A relational spirituality framework. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 805–827.

Manning, J. C. (2006). The impact of internet pornography on marriage and the family: A review of the research. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 13, 131–165.

Olmstead, S. B., Negash, S., Pasley, K., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). Emerging adults expectations for pornogrpahy use in the context of future committed romantic relationships: A qualitative study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 625–635.

Patterson, R., & Price, J. (2012). Pornography, religion, and the happiness gap: Does pornography impact the actively religious differently? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51, 79–89.

Paul, P. (2005). Pornified: How pornography is transforming our lives, relationships, and our families. New York: Times Books.

Perry, S. L. (2015). Pornography consumption as a threat to religious socialization. Sociology of Religion, 76, 436–458.

Perry, S. L. (2016a). From bad to worse? Pornography consumption, spousal religiosity, gender, and marital quality. Sociological Forum, 31, 441–464. doi:10.1111/socf.12252.

Perry, S. L. (2016b). Does viewing pornography diminish religiosity over time? Evidence from two-wave panel data. Journal of Sex Research. doi:10.1080/00224499.2016.1146203.

Perry, S. L. (in press). Spousal religiosity, religious bonding, and pornography consumption. Archives of Sexual Behavior.

Poulsen, F. O., Busby, D. M., & Galovan, A. M. (2013). Pornography use: Who uses it and how it is associated with couple outcomes. Journal of Sex Research, 50, 72–83.

Schneider, J. P. (2000). Effects of cybersex addiction on the family: Results of a survey. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 7, 31–58.

Short, M. B., Black, L., Smith, A. H., Wetterneck, C. T., & Wells, D. E. (2012). A review of internet pornography use research: Methodology and content from the past 10 years. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15, 13–23.

Short, M. B., Kasper, T. E., & Wetterneck, C. T. (2015). The relationship between religiosity and internet pornography use. Journal of Religion and Health, 54, 571–583.

Stack, S., Wasserman, I., & Kern, R. (2004). Adult social bonds and use of internet pornography. Social Science Quarterly, 85, 75–88.

Steensland, B., Park, J. Z., Regnerus, M. D., Robinson, L., Wilcox, W. B., & Woodberry, R. (2000). The measure of American religion: Toward improving the state of the art. Social Forces, 79, 291–318.

Stewart, D. N., & Szymanski, D. M. (2012). Young adult women’s reports of their male romantic partner’s pornography use as a correlate of their self-esteem, relationship quality, and sexual satisfaction. Sex Roles, 67, 257–271.

Traeen, B., Nilsen, T. S., & Stigum, H. (2006). Use of pornography in traditional media and on the Internet in Norway. Journal of Sex Research, 43, 245–254.

Weinberg, M. S., Williams, C. J., Kleiner, S., & Irizarry, Y. (2010). Pornography, normalization, and empowerment. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 1389–1401.

Wilkins, A. S. (2014). To lag or not to lag? Re-evaluation of the use of lagged dependent variables in regression analyses. Unpublished manuscript. http://web.stanford.edu/~arjunw/LaggedDVs.pdf accessed on September 10, 2015.

Willoughby, B. J., Carroll, J. S., Busby, D. M., & Brown, C. C. (2016). Differences in pornography use among couples: Associations with satisfaction, stability, and relationship processes. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 145–158.

Wright, P. J. (2013). U.S. males and pornography, 1973-2010: Consumption, predictors, and correlates. Journal of Sex Research, 50, 60–71.

Wright, P. J., Bae, S., & Funk, M. (2013). United States women and pornography through four decades: Exposure, attitudes, behaviors, and individual differences. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 1131–1144.

Yucel, D., & Gassanov, M. A. (2010). Exploring actor and partner correlates of sexual satisfaction among married couples. Social Science Research, 39, 725–738.

Zillmann, D., & Bryant, J. (1988). Pornography’s impact on sexual satisfaction. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 18, 438–453.

Zitzman, S. T., & Butler, M. H. (2009). Wives’ experience of husbands’ pornography use and concomitant deception as an attachment threat in the adult pair-bond relationship. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 16, 210–240.

Funding

This study did not receive any direct funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants by the author. Secondary data were used.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perry, S.L. Does Viewing Pornography Reduce Marital Quality Over Time? Evidence from Longitudinal Data. Arch Sex Behav 46, 549–559 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0770-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0770-y