Abstract

Double emulsions attract considerable interest for their utility in applications as diverse as drug delivery, contrast agents, and compartmentalizing analytes for fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Microfluidic platforms offer a particularly elegant approach to generating these structures, but the construction of devices to provide reproducible and stable production of double emulsions remains challenging. PDMS-based systems require specialized surface treatments that are difficult to implement and lack long-term stability, and current glass microcapillary systems, while offering some advantages, lack flexible and reproducible methods for capillary alignment. This article describes a microcapillary-based approach that addresses these key challenges. Our approach utilizes translational stage elements and alignment end caps that are fixed in place once configured, rather than tightly fitting capillaries. This new approach enables alignment to within ±10 µm and allows greater flexibility in choosing the dimensions of the capillary, which contributes to the size and stability of formation of the double emulsion. Importantly, it also allows the user to compensate for the deviations from ideal shape that occur in pulled glass capillaries, which has been a source of failure with previous methods. A detailed description of the critical design and operational parameters that affect double emulsion generation in these capillary microfluidic devices is provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The last two decades have seen great progress in the use of microfluidic technologies to miniaturize biological, chemical, and medical processes. Droplet microfluidics in particular has enabled new modes for cell sorting and analysis (Eun et al. 2011; Mazutis et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013), single molecule immunoassays (Shim et al. 2013), directing biomolecule evolution (Agresti et al. 2010; Kintses et al. 2012), and the synthesis of crystals (Lignos et al. 2014; Phillips et al. 2014; Yashina et al. 2012), contrast agents (Abbaspourrad et al. 2013), and drug delivery particles (Leon et al. 2014; Xu et al. 2009)—among other advances (Casadevall i Solvas and deMello 2011; Guo et al. 2012; Song et al. 2006; Teh et al. 2008; Theberge et al. 2010). However, in spite of the great potential of microfluidics (Whitesides 2006), these devices are still not routinely used by non-specialists, due in part to the demands of device fabrication and the almost inevitable need to trouble-shoot (Whitesides 2013; Yetisen et al. 2013). Highlighted in a recent push to extend the viability of microfluidic devices for commercial and industrial products (Whitesides 2014), many groups have sought to provide engineering solutions to the existing technical obstacles. Some of the challenges that have been addressed include the removal and prevention of unwanted air bubbles (Nakayama et al. 2006; Zheng et al. 2010), improving world-to-chip connection (Fredrickson and Fan 2004; Liu et al. 2003; Yang et al. 2008), eliminating the need for large external syringe pumps (Tang et al. 2014), reducing cross contamination (Yang et al. 2008), elevating the importance of sample collection and preparation (Labuz and Takayama 2014), and overcoming solvent volatility (Gunawan et al. 2014).

In an effort to improve the robustness and functionality of droplet microfluidic platforms, some devices have been constructed from nested glass microcapillaries as an alternative to more conventional materials such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (Chu et al. 2007; Kim et al. 2007, 2013; Shah et al. 2008; Utada et al. 2005). These microcapillary devices rely on coaxial alignment of the nested capillaries and can be used to generate both single and multiple emulsion droplets depending on the number and configuration of the fluid flows (Shah et al. 2008). Double emulsion generation has been achieved by inserting a pulled capillary and an outlet capillary into opposite ends of a larger capillary of square cross section, where selecting inner capillaries of an outer diameter equal to the inner side length of the square capillary provides coaxial alignment (Utada et al. 2005). As is also true of PDMS-based devices, no standardized fluidic connections exist and syringe needles are often used as improvised inlets and outlets (Kim et al. 2013). These factors, together with problems with reproducibility, may have contributed to the limited use of such capillary devices in recent years.

These challenges have led us, and others (Benson et al. 2013; Chang et al. 2009), to pursue new routes for reproducible device construction. For instance, deMello and co-workers designed an elegant 3D-printed screw and nut assembly which could be used to align glass capillaries for the controlled generation of oil-in-water-in-oil (O/W/O) and water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W) double emulsions (Martino et al. 2014). In their device, screws that hold the capillaries for both inner fluid introduction and droplet collection are inserted into nuts fixed to opposite sides of a larger outer capillary of either square or circular cross section. This configuration allows the distance between inner capillaries to be controlled by simply turning the screws. However, while this design offers greater standardization and versatility, devices often fail to generate double emulsions due to the inability to control the alignment of inner capillaries, and thus allow for variations in their shapes.

In this article, we describe a highly controllable approach to capillary microfluidic device construction, which utilizes specially designed poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) end caps to achieve capillary alignment and to present precisely defined inlet ports for all source flows. The end caps and the capillaries they contain are assembled using an alignment rig that allows us to define capillary position to within ±10 µm. This enables adjustment of both the perpendicular spacing between internal capillaries and their lateral alignment with each other, which becomes a significant factor in light of the inevitable asymmetries present in pulled glass capillaries. Additionally, this assembly process increases the reproducibility within and between batches of devices, and the usage of cylindrical outer capillaries rather than tightly fitting square capillaries enables the flexibility to employ a range of capillary sizes and inner/outer capillary diameter ratios. We envision the introduced end caps as an initial step toward the construction of robust glass microfluidic devices of increasing complexity that could support further adoption of microfluidic double emulsion production for commercial applications.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Device fabrication

A new assembly method and device for microfluidic double emulsion generation that could readily compensate for the asymmetries that occur in pulled glass capillaries were developed. Each microcapillary device consists of three primary components: an outer thick-walled capillary, an inlet pulled capillary, and a collection capillary, the dimensions of which are listed in Table 1S in the Electronic Supplementary Material. Pulled inlet capillaries were purchased from World Precision Instruments (WPI, Sarasota, FL) and FIVEphoton (FP, San Diego, CA), and the thick-walled outer capillaries were cut into shorter lengths with a hand-held glass cutter. Collection capillaries were modified through axial heating at the tip by exposing them to a direct flame (a hand-held lighter) for a few seconds as described by Utada et al. (2005). This creates a nozzle-like structure (Fig. 1c) that contracts and then expands the fluid flow to encourage droplet breakup and emulsification. This heating procedure was found to be a controllable and inexpensive process where several capillaries of similar nozzle size and shape can be produced in 5 min. After heating, the capillaries were optically inspected to ensure that they had melted symmetrically. Other methods used to create such nozzles require the deformation of tapered glass capillaries using microforges (Martino et al. 2014), which are expensive and uncommon in most laboratories, or by hand using mechanical scoring (see Sect. 3.1).

To ensure proper surface wetting for generation of either O/W/O or W/O/W emulsions, the glass surfaces were chemically modified with a silane before assembly. For O/W/O production, pulled capillaries were made hydrophilic and the collection and outer capillaries were made hydrophobic; the treatments were reversed for W/O/W production. Treatments were performed by placing the capillaries in a vacuum desiccator for 1 h with either 100 µL of trichloro(1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl)silane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for a hydrophobic surface or 2-[methoxy(polyethyleneoxy)propyl]trimethoxysilane (Gelest, Morrisville, PA) for a hydrophilic surface. The liquid silanes evaporate in vacuo, and the vapor coats the surface of the glass. The pre-treatment cleaning procedure for all glassware is included in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

PMMA end caps that hold the pulled and collection capillaries in place were used to aid device assembly and provide final device structure (Fig. 1). A CNC (computer numerical control) sliding head lathe (Cincom L12, Citizen Machinery, Bushey, UK) was used to quickly and accurately produce batches of end caps, each of which contains a large recess into which the outer capillary fits. The end cap is also manufactured to comprise a smaller recess containing a hole through its center through which the pulled or the collection capillary is inserted (Fig. 1a, left or right internal capillary, respectively). These holes are made larger than the diameter of the capillaries, so that the capillaries may be externally manipulated for alignment (as will be described shortly). Radial holes are drilled into the small recess for the insertion of the tubing that supplies either the middle or outer fluid. A final radial hole is made as a conduit for the epoxy which is used to seal off the entrance for the capillaries once the device has been aligned (Fig. 1a). The cylindrical shape of the end caps allows the device to be easily rotated during operation to view the flow from different directions.

The capillary devices were designed to enable the placement and alignment of each individual pulled glass capillary. This was achieved with a precision of ±10 µm (limited by visualization software) using an alignment rig designed in-house with commercial optomechanical components (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ). The rig consists of three main parts: a stationary central V-block which is used to hold the large outer capillary and two V-blocks attached to translational stage elements which are used to hold the pulled capillary and the collection capillary. During construction of the alignment rig, the three V-blocks are pre-aligned in the Z-direction (Fig. 2, out of plane). The V-block holding the collection capillary can be manipulated in the Y-direction, while the V-block holding the pulled capillary can be manipulated in the X- and Y-directions using the micrometers that position the stages. The maximum possible misalignment that can be corrected without material deformation is limited by the difference in the outer diameter of the pulled capillary and the inner diameter of the outer capillary (i.e., the pulled capillary cannot be manipulated beyond where it will meet the inner wall of the outer capillary). With the capillary dimensions used in this study, the greatest misalignment that can be corrected is 250 µm (pulled capillary OD: 1.0 mm; outer capillary ID: 1.5 mm). The two inner capillaries can be carefully manipulated, with the aid of a digital microscope (Dino-Lite, Hsinchu, Taiwan) attached to the rig. These capillaries are centrally aligned (d 1 in Fig. 2b) and positioned at specific distances from one another (d 2 in Fig. 2b, further illustrated in Figs. 1S and 2S). This greatly improves reproducibility as devices with identical capillary spacings can be manufactured. Each device can be assembled in approximately 45 min (excluding epoxy hardening time). A full description of the assembly procedure can be found in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

a Photograph showing the alignment rig for capillary device assembly; the Z-direction is out of the page. b View from the camera which aids the alignment of the pulled and collection capillaries. Both capillaries can be adjusted in the Y-direction to position the tip in the center of the nozzle (d 1), and the pulled capillary (on the left manipulator) can be adjusted in the X-direction to control spacing between the tip and collection nozzle (d 2)

2.2 Double emulsion generation

In this study, devices were operated using neMESYS computer-controlled syringe pumps (Cetoni, Korbußen, Germany). Observations were made with a SteREO Discovery V8 microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and recorded using a Genie HC640 Gigabit Ethernet camera with a CMOS sensor (Teledyne DALSA, Ontario, CA). Video images were recorded between 100 and 150 frames per second (fps). O/W/O experiments were performed with an inner fluid of silicone oil with a kinematic viscosity of 5 cSt, a middle fluid of 10 vol% glycerol solution with added dye, and an outer fluid of silicone oil with a kinematic viscosity of 10 cSt. W/O/W testing was conducted with an inner fluid of deionized water with dye, a middle fluid of mineral oil with 20 mg/mL Span 80, and an outer fluid of 20 vol% glycerol. Interfacial tensions utilized ranged from 3.1 to 35.9 mN m−1, where the change in surface tension due to the presence of dissolved glycerol in the water phase was less than 1 mN m−1 (Baldelli et al. 1997). Rheological measurements were performed to confirm Newtonian behavior of all fluids; a table of fluid properties is given in the Electronic Supplementary Material (Table 2S) (Peters and Arabali 2013; Zhou et al. 2013).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Pulled capillary analysis

We observed that devices in which the body (not the tip) of the pulled inlet capillary and the collection capillary were positioned with perfect coaxial alignment (Fig. 3b) frequently failed to generate double emulsions. This can be attributed to the asymmetry present in the majority of pulled glass capillaries, where the tip orifice is typically offset with respect to the capillary axis. It is probable that these defects are caused by non-uniform heating during tip pulling procedures (e.g., greater heating from one side). Originally developed for use in electrophysiology (Brown and Flaming 1977), tapered micropipettes or capillaries are formed by heating a glass capillary between two heated metal filaments. These filaments are then cooled by a single or multiple air jets, while at the same time the capillary is mechanically pulled apart until breaking into two tapered pipettes (Brown et al. 2008; Oesterle 2011). Any variation in the filament distance or air jet properties may cause unpredictable taper alterations. By varying heating and pulling parameters, different length tapers and tip diameters can be achieved. However, to make capillaries with tip diameters >1 µm common for capillary-based microfluidics, Sutter Instruments (Novato, CA) recommends some form of mechanical scoring and deformation to break the glass to the desired tip size (Oesterle 2011). This introduces even more variability into the tip fabrication process.

a Optical micrograph of a pulled capillary with a misalignment distance, d mis, of ~100 µm; b Schematic diagram of pulled (bottom) and collection (top) capillaries illustrating that even when capillaries are axially aligned, there is misalignment due to d mis; c Box plots showing the distribution of misalignment distances as a percentage of the radius, 0.5 mm, of pulled capillaries. WPI and FP stand for World Precision Instruments and FIVEphoton, respectively. 10 and 30 denote tip diameter in micrometers. Upper and lower whiskers indicate the maximum and minimum values calculated, respectively

The extent of these defects, which was recorded as the misalignment distance or d mis (Fig. 3a), was assessed for a total of 19 pre-pulled borosilicate tips of 10 and 30 µm diameter, obtained from World Precision Instruments and FIVEphoton. Capillary tips were placed under a stereo microscope and manually rotated until the plane of greatest misalignment was observed. Captured images were processed in ImageJ, and the perpendicular deviation from the center axis was recorded and converted to a percentage of the capillary radius of 0.5 mm (Fig. 3c). The average d mis of all measured tips was 64 µm with a standard deviation of 36 µm. This represents a significant deviation when compared with a collection capillary nozzle of 200–300 µm diameter, and its effect will be further compounded by any imprecision in the assembly process itself. As previous device designs have been unable to compensate for the asymmetry of the pulled glass capillaries, they have therefore struggled to reproducibly generate double emulsions (Fig. 3S in the Electronic Supplementary Material).

3.2 Droplet production

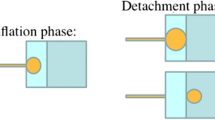

End cap-aligned capillary devices enable the controllable generation of both O/W/O and W/O/W emulsions at comparable flow rates. In common with previous capillary systems (Chu et al. 2007; Utada et al. 2005), our device allows droplet formation to be tuned by varying relative fluid flow rates, where this provides control over the rate of droplet generation, the distances between droplets, outer droplet size, and the number of inner droplets per single emulsion (Fig. 4). For instance, by increasing the inner flow rate and leaving the flow rates of the middle and outer constant, the number of internal droplets can be doubled (e.g., from two inner droplets in Fig. 4b to four inner droplets in Fig. 4c). Droplet production in each of the cases shown in Fig. 4 occurred in the dripping regime. As established in the literature (Utada et al. 2007a) and reaffirmed in tests with end cap devices, the most consistent and reproducible droplet generation occurs under these conditions. Double emulsion generation within end cap devices is stable with time, where devices have produced double emulsions consistently for an hour, with production ceasing only when the flows are stopped. The frame-by-frame production of a double emulsion with one internal droplet can be seen in Fig. 5.

a–d W/O/W droplet generation with a collection nozzle of ~300 µm diameter and 90 µm distance from the tip. Flow rates of fluids are given in µL/min in the form of Q IF/Q MF/Q OF. a Single internal droplet: 1/25/30; b two internal droplets: 3/30/45; c four internal droplets: 5/35/45; d small droplet array: 5/30/45; (e–h) O/W/O droplet generation with collection nozzle of ~250 µm diameter and 75 µm distance from tip; e single internal droplet: 10/50/50; f single internal droplet at 2.5× the generation frequency of e: 20/100/100; g smaller outer droplets with two internal droplets: 10/50/100; h four internal droplets: 25/50/100. Scale bars are 0.5 mm

In most experiments with the O/W/O and W/O/W systems, the Weber numbers \((We = \rho dv^{2} \gamma^{ - 1} )\) and capillary numbers \((Ca = \mu v\gamma^{ - 1} )\) were less than unity, meaning that interfacial forces dominated over both inertial and viscous forces at these operating conditions of the end cap devices (Nie et al. 2008; Utada et al. 2007b). In these equations ρ, v and γ are the density (kg m−3), velocity (m s−1), and interfacial tension (N m−1) of a particular fluid phase, respectively, and d is the hydraulic diameter (m) of the flow channel. However, inertial and viscous forces still play a role in determining the flow characteristics. Utada et al. (2007b) reported that the dripping-to-jetting transition of a co-flowing capillary geometry for single emulsion generation (diphasic flow) occurs when the sum of the Weber number of the dispersed phase and capillary number of the continuous phase is approximately equal to unity (i.e., jetting occurs at sums approaching or greater than unity). We applied a similar analysis, including the Weber number of both dispersed phases, to the triphasic flow within end cap devices and found the transition to be consistent with their result.

In order to further characterize flow within end cap devices, we assessed four conditions where jetting was observed (Fig. 6). These conditions were chosen to emphasize the contribution of different forces to middle phase jetting. In Fig. 6a, when the capillary number of the outer phase (Ca out) and Weber number of the middle phase (We mid) were both <0.1, jetting occurred and was primarily due to the forward momentum of the innermost phase (We in ≈ 0.5). Here, the sum of the capillary number of the outermost phase and the Weber number of both dispersed phases was equal to ~0.6 (i.e., Ca out + We mid + We in ≈ 0.6). In Fig. 6b, Ca out and We mid were comparable to the experiments shown in Fig. 6a, yet We in was increased by an order of magnitude (We in ≈ 5.0). In this instance, the jet extended out of the view of the microscope to an estimated length of 1 cm. From these results, it is clear that the inertial force of the innermost phase can cause jetting of the middle phase. In Fig. 6c, jetting is attributed to a combination of outer phase shearing and middle phase inertia, as low We in indicates the inertial force of the inner phase was negligible. When the inner phase momentum was increased in Fig. 6d, some stabilization of the jet was seen, but the distance to pinch off remained relatively unchanged. Jetting was not observed for the O/W/O system under any conditions, due to the high interfacial tension of the water-silicone oil interface without surfactant. Table 3S in the Electronic Supplementary Material contains the relevant dimensionless parameters for each flow scenario presented in Figs. 4 and 6.

Jetting observed for the W/O/W system in end cap devices. Flow rates of fluids are given in µL/min in the form of Q IF/Q MF/Q OF. a Jetting due to We in: 10/40/75; b long jet due to We in: 30/50/90; c jetting due to Ca out and We mid: 2/100/175; d jetting due to Ca out, We mid, and We in: 10/100/175. Scale bar is 0.5 mm

3.3 Design and operational observations

In addition to fabricating a device which could reproducibly generate double emulsions, we also sought to identify problems with earlier designs and the effects that critical device parameters have on device operation and flow. We encountered two main problems in the operation of devices like those of Utada et al. (2005), where middle and outer flows are introduced between gaps in tightly fitting inner and outer capillaries. This tight fit restricts the flow of the middle and outer phases to the four inner edges of the square capillary, effectively dividing each fluid into four separate streams. We found that when viscous fluids with high interfacial tension were subjected to this flow pattern they resisted coalescence, creating chaotic fluid interactions at the capillary junction that prevented the streams from merging and impeding emulsification. Utilizing a cylindrical outer capillary solved this flow problem and provided uniform flow around internal capillaries. Additionally, since the configuration offered by end cap alignment in our device does not require the outer and inner capillaries to fit tightly together, capillaries with a range of sizes can be used. The second problem encountered was in the axial misalignment of the pulled capillary orifice with the axial center of the outlet capillary (d mis) (Fig. 3b). It is clearly extremely difficult to achieve controllable emulsion production in devices with large misalignment distances. In addition to causing non-uniform shear to droplets forming on the tip, severe misalignments can completely hinder inner droplet production. In one such case, which is illustrated in Fig. 3S in the Electronic Supplementary Material, the misalignment results in the tip being exposed to the continuous phase where the inner and outer fluids mix.

As has been described previously (Kim et al. 2013), the surface properties of the capillary walls are critical for achieving double emulsion generation. As observed for the O/W/O system, without modification of the collection capillary, the aqueous (middle) phase wets the internal wall of the collection capillary, preventing continuous flow of the outer oil phase into the collection nozzle. In this case, the oil phase is sheared by the aqueous phase, leading to segmented flow comprising alternating oil and water segments. Similar observations of alternating flow patterns have been made by Dreyfus et al. (2003) (isolated structure pattern) and Cubaud and Mason (2008) (viscous displacement loop). In contrast, when the collection capillary is made hydrophobic via surface treatment, it is preferentially wetted by the outer oil flow. This focuses the water flow to the middle of the collection nozzle and permits continuous flow of the outer oil phase. The order of fluid introduction into the device also plays a part in this, where introducing the outer fluid first further ensures it preferentially wets the collection nozzle over the middle fluid. Although this effect is more pronounced in the O/W/O system, since untreated glass allows for partial water wetting, surface treatment of the collection capillary also increases the stability of droplet production in W/O/W systems.

The surface modification of the pulled capillary is also important for controllable droplet production. The external surface of the pulled capillary must be functionalized if it is to be preferentially wetted by the middle phase. This modification helps to prevent two scenarios: (1) non-uniform flow of the middle phase around the pulled capillary, and thus uneven shearing of the inner phase and (2) the wetting of the outer surface of the tip by the innermost phase. In the second scenario, as a droplet forms on the tip, surface forces will pull it up along the taper in opposition to the flow rather than enabling it to detach and enter the collection capillary. At low Ca numbers, where interfacial forces dominate over viscous forces, this parasitic flow pattern can be seen if the inner phase’s affinity for the pulled capillary surface is too high. Figure 4S in the Electronic Supplementary Material illustrates the optimum surface chemistries for each system.

While less important than the functionalization of the internal capillaries, the surface properties of the outer capillaries can also be tailored to improve the flow. The outer capillaries were treated in the same way as the collection capillaries to enable continuous phase wetting. This ensures that the three-phase contact line (where the middle and outer phases meet the surface of the outer capillary) is positioned to allow for the creation of a conical middle phase flow profile, analogous to the Taylor cone observed in electro-hydrodynamic flow focusing (Loscertales et al. 2002). The formation of this cone is affected by both the position of the contact line and also the velocity of the middle phase at the collection nozzle.

As stated earlier, wetting of the collection nozzle by the middle phase results in the formation of alternating segments of oil and water, where each phase excludes the other until pressure build up in the blocked phase causes a flow reversal. When the outer phase excludes the middle phase, it causes the middle phase to retract upstream from the nozzle and form a flat interface with the outer phase perpendicular to the direction of flow. Dependent on the spacing between the tip of the pulled capillary and the collection nozzle (d 2, Fig. 2b), this retraction could expose the tip to the outer flow and therefore inhibit inner droplet formation. Nie et al. (2008) described two modes (R1 and R2) of droplet breakup characterized by this retraction in a flow focusing geometry. In mode R1, the discontinuous phase makes a large retraction from the focusing nozzle back to its inlet after droplet pinch off. Conversely, at higher flow rates, mode R2 droplet generation was observed where the discontinuous phase only slightly retracts and remains at the nozzle. For most spacing distances (d 2), mode R2 droplet generation of the middle phase is required to ensure that the tip is not exposed to the outer phase after droplet breakup. However, misalignment of the tip exacerbates the effects of both mode R1 and R2 retractions as well as those caused by breakdown of the Taylor cone. This makes the junction more sensitive to these perturbations. Figure 5S in the Electronic Supplementary Material illustrates a flow in which unstable droplet generation occurs in the absence of a Taylor cone.

One of the most critical elements in the production of double emulsions is the shearing of the droplets that form on the tip of the pulled capillary. When these droplets are insufficiently sheared, they remain attached and continue to grow until there is sufficient drag force to overcome the surface tension pinning them to the tip (Umbanhowar et al. 2000). If the shear force is sufficiently low, no amount of drag can overcome surface tension, and a droplet will grow until it blocks the entire width of the channel. In this case, pressure build up in the middle phase eventually leads to breakup in the same way as in T-junctions in low Ca regimes (Garstecki et al. 2006). Sufficient shear of the innermost fluid can be obtained in a variety of ways. The shear force on a droplet is proportional to both the viscosity and velocity of the middle fluid, where this is seen in the equation for drag force (F D ) on a forming droplet:

where µ mid is the dynamic viscosity of the middle phase, (d drop − d tip) is the diameter of the forming droplet minus the outer diameter of the tip, and (v mid − v drop) is the relative velocity between the middle phase and the droplet (Umbanhowar et al. 2000). The viscosity of the middle phase has a direct effect on the amount of shear force that it applies to forming inner droplets. If the viscosity ratio between the fluids (µ in/µ mid) is greater than unity—which is common in O/W/O droplet production—a higher middle phase velocity will be required to generate the necessary shear force. The relative velocity between phases can be controlled by adjusting the ratio of inner and middle flow rates or by modifying the distance between the tip of the pulled capillary and the collection nozzle (d 2). Upstream of the nozzle, the flow of the middle phase fills the entire area between the pulled capillary and the outer capillary. However, as the flow approaches the nozzle it is hydrodynamically focused by the outer fluid, resulting in a smaller flow area and higher velocity. Therefore, the closer the pulled capillary is positioned with respect to the nozzle (small d 2), the greater the middle phase velocity, and therefore the shear force, will be at the tip. The maximum velocity achieved is also dependent on the diameter of the nozzle. In order to attain the correct shear force for steady droplet production, the viscosity and velocity ratio, the tip-nozzle spacing, and nozzle size must be properly balanced. For our experimental conditions with nozzle sizes on the order of ~250 µm, we found a tip-nozzle spacing of 50–100 µm to be optimal.

The importance of utilizing surfactants to lower the interfacial tension was also examined. Figure 6S in the Electronic Supplementary Material illustrates a W/O/W flow condition where 5 cSt silicone oil without surfactant was employed as the middle phase. Here, the high interfacial tension between the inner and middle phases impeded flow out of the pulled tip in spite of proper surface wetting, shear force, and Taylor cone creation. This induced a pressure build up in the inner fluid which produced a strong jet that merged with the continuous phase after outer droplet pinch off.

4 Conclusions

Glass microcapillaries offer many advantages for droplet production over PDMS or other microfabricated channels, but suffer problems with reliable droplet generation and incorporation into complex microfluidic systems. This article describes a new method, based on alignment end caps and translational stage elements, which allows the easy assembly of capillary-based microfluidic devices for a range of applications. Importantly, our approach enables the accurate positioning of both the perpendicular distance between internal capillaries and the lateral alignment of the pulled capillary with respect to the collection nozzle, which allows the user to readily compensate for the asymmetry that occurs in the majority of pulled glass capillaries. It also facilitates the use of cylindrical capillaries, which provide more uniform flow and dimensional selectivity than can be achieved using the rectangular capillaries employed in previous systems. Systematic study of the operation of our device identified several technical considerations that must be made in device design, assembly, and operation. It is our expectation that identification of the key parameters leading to stable emulsion production will enable researchers outside the core microfluidics community to adopt and benefit from such double emulsion-generating capillary devices.

Our device design could also be extended through the inclusion of joints, valves, and connectors to generate complex, and potentially multi-dimensional capillary microfluidic devices similar to the 3D-printed polymer assemblies of Bhargava et al. (2014). Such a connector set would help advance the utility of microfluidic systems for the processing and screening of chemical reactions and biological processes, while the robust nature of a glass-based system makes it well suited to many industrial and commercial applications. To make such a commercial system viable, each junction would require a flow stability and robustness not often found in devices used in academic environments. Start-up and operation would also have to be possible based on observations made using the naked eye. Our device goes some way toward addressing these requirements, where the large channel size and flow stability enable its operation without a microscope. Notably, the end cap tools employed in this work were made without the use of a clean room and could be employed in any laboratory equipped with a syringe pump. Future work with this microfluidic construction approach will explore the integration of additional downstream processing and analysis components within a single microcapillary device. The stability and efficiency of inner droplet encapsulation over long production cycles (>1 h) could also be studied and optimized for industrial usage.

References

Abbaspourrad A, Duncanson WJ, Lebedeva N, Kim SH, Zhushma AP, Datta SS, Dayton PA, Sheiko SS, Rubinstein M, Weitz DA (2013) Microfluidic fabrication of stable gas-filled microcapsules for acoustic contrast enhancement. Langmuir 29:12352–12357

Agresti JJ, Antipov E, Abate AR, Ahn K, Rowat AC, Baret JC, Marquez M, Klibanov AM, Griffiths AD, Weitz DA (2010) Ultrahigh-throughput screening in drop-based microfluidics for directed evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:4004–4009

Baldelli S, Schnitzer C, Shultz MJ, Campbell DJ (1997) Sum frequency generation investigation of glycerol/water surfaces. J Phys Chem B 101:4607–4612

Benson BR, Stone HA, Prud’homme RK (2013) An “off-the-shelf” capillary microfluidic device that enables tuning of the droplet breakup regime at constant flow rates. Lab Chip 13:4507–4511

Bhargava KC, Thompson B, Malmstadt N (2014) Discrete elements for 3d microfluidics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:15013–15018

Brown KT, Flaming DG (1977) New micro-electrode techniques for intracellular work in small cells. Neuroscience 2:813–827

Brown AL, Johnson BE, Goodman MB (2008) Making patch-pipettes and sharp electrodes with a programmable puller. J Vis Exp. doi:10.3791/939

Casadevall i Solvas X, deMello A (2011) Droplet microfluidics: recent developments and future applications. Chem Commun 47:1936–1942

Chang ZQ, Serra CA, Bouquey M, Prat L, Hadziioannou G (2009) Co-axial capillaries microfluidic device for synthesizing size- and morphology-controlled polymer core-polymer shell particles. Lab Chip 9:3007–3011

Chu L-Y, Utada AS, Shah RK, Kim J-W, Weitz DA (2007) Controllable monodisperse multiple emulsions. Angew Chem Int Ed 46:8970–8974

Cubaud T, Mason TG (2008) Capillary threads and viscous droplets in square microchannels. Phys Fluids 20:11

Dreyfus R, Tabeling P, Willaime H (2003) Ordered and disordered patterns in two-phase flows in microchannels. Phys Rev Lett 90:144505

Eun Y-J, Utada AS, Copeland MF, Takeuchi S, Weibel DB (2011) Encapsulating bacteria in agarose microparticles using microfluidics for high-throughput cell analysis and isolation. ACS Chem Biol 6:260–266

Fredrickson CK, Fan ZH (2004) Macro-to-micro interfaces for microfluidic devices. Lab Chip 4:526–533

Garstecki P, Fuerstman MJ, Stone HA, Whitesides GM (2006) Formation of droplets and bubbles in a microfluidic t-junction—scaling and mechanism of break-up. Lab Chip 6:437–446

Gunawan CA, Ge MC, Zhao C (2014) Robust and versatile ionic liquid microarrays achieved by microcontact printing. Nat Commun 5:3744

Guo MT, Rotem A, Heyman JA, Weitz DA (2012) Droplet microfluidics for high-throughput biological assays. Lab Chip 12:2146–2155

Kim J-W, Utada AS, Fernandez-Nieves A, Hu Z, Weitz DA (2007) Fabrication of monodisperse gel shells and functional microgels in microfluidic devices. Angew Chem Int Ed 46:1819–1822

Kim S-H, Nam J, Kim JW, Kim D-H, Han S-H, Weitz DA (2013) Formation of polymersomes with double bilayers templated by quadruple emulsions. Lab Chip 13:1351–1356

Kintses B, Hein C, Mohamed MF, Fischlechner M, Courtois F, Leine C, Hollfelder F (2012) Picoliter cell lysate assays in microfluidic droplet compartments for directed enzyme evolution. Chem Biol 19:1001–1009

Labuz JM, Takayama S (2014) Elevating sampling. Lab Chip 14:3165–3171

Leon RAL, Wan WY, Badruddoza AM, Hatton TA, Khan SA (2014) Simultaneous spherical crystallization and co-formulation of drug(s) and excipient from microfluidic double emulsions. Cryst Growth Des 14:140–146

Lignos I, Protesescu L, Stavrakis S, Piveteau L, Speirs MJ, Loi MA, Kovalenko MV, deMello AJ (2014) Facile droplet-based microfluidic synthesis of monodisperse iv-vi semiconductor nanocrystals with coupled in-line nir fluorescence detection. Chem Mater 26:2975–2982

Liu J, Hansen C, Quake SR (2003) Solving the “world-to-chip” interface problem with a microfluidic matrix. Anal Chem 75:4718–4723

Loscertales IG, Barrero A, Guerrero I, Cortijo R, Marquez M, Ganan-Calvo AM (2002) Micro/nano encapsulation via electrified coaxial liquid jets. Science 295:1695–1698

Martino C, Berger S, Wootton RCR, deMello AJ (2014) A 3d-printed microcapillary assembly for facile double emulsion generation. Lab Chip 14:4178–4182

Mazutis L, Gilbert J, Ung WL, Weitz DA, Griffiths AD, Heyman JA (2013) Single-cell analysis and sorting using droplet-based microfluidics. Nat Protoc 8:870–891

Nakayama T, Kurosawa Y, Furui S, Kerman K, Kobayashi M, Rao SR, Yonezawa Y, Nakano K, Hino A, Yamamura S, Takamura Y, Tamiya E (2006) Circumventing air bubbles in microfluidic systems and quantitative continuous-flow pcr applications. Anal Bioanal Chem 386:1327–1333

Nie ZH, Seo MS, Xu SQ, Lewis PC, Mok M, Kumacheva E, Whitesides GM, Garstecki P, Stone HA (2008) Emulsification in a microfluidic flow-focusing device: effect of the viscosities of the liquids. Microfluid Nanofluid 5:585–594

Oesterle A (2011) The pipette cookbook. Sutter Instrument Company. http://www.sutter.com/PDFs/pipette_cookbook.pdf. Accessed 9 Oct 2014

Peters F, Arabali D (2013) Interfacial tension between oil and water measured with a modified contour method. Colloids Surf A 426:1–5

Phillips TW, Lignos IG, Maceiczyk RM, deMello AJ, deMello JC (2014) Nanocrystal synthesis in microfluidic reactors: where next? Lab Chip 14:3172–3180

Shah RK, Shum HC, Rowat AC, Lee D, Agresti JJ, Utada AS, Chu L-Y, Kim J-W, Fernandez-Nieves A, Martinez CJ, Weitz DA (2008) Designer emulsions using microfluidics. Mater Today 11:18–27

Shim J-U, Ranasinghe RT, Smith CA, Ibrahim SM, Hollfelder F, Huck WTS, Klenerman D, Abell C (2013) Ultrarapid generation of femtoliter microfluidic droplets for single-molecule-counting immunoassays. ACS Nano 7:5955–5964

Song H, Chen DL, Ismagilov RF (2006) Reactions in droplets in microflulidic channels. Angew Chem Int Ed 45:7336–7356

Tang SY, Khoshmanesh K, Sivan V, Petersen P, O’Mullane AP, Abbott D, Mitchell A, Kalantar-zadeh K (2014) Liquid metal enabled pump. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:3304–3309

Teh SY, Lin R, Hung LH, Lee AP (2008) Droplet microfluidics. Lab Chip 8:198–220

Theberge AB, Courtois F, Schaerli Y, Fischlechner M, Abell C, Hollfelder F, Huck WTS (2010) Microdroplets in microfluidics: an evolving platform for discoveries in chemistry and biology. Angew Chem Int Ed 49:5846–5868

Umbanhowar PB, Prasad V, Weitz DA (2000) Monodisperse emulsion generation via drop break off in a coflowing stream. Langmuir 16:347–351

Utada AS, Lorenceau E, Link DR, Kaplan PD, Stone HA, Weitz DA (2005) Monodisperse double emulsions generated from a microcapillary device. Science 308:537–541

Utada AS, Chu LY, Fernandez-Nieves A, Link DR, Holtze C, Weitz DA (2007a) Dripping, jetting, drops, and wetting: the magic of microfluidics. MRS Bull 32:702–708

Utada AS, Fernandez-Nieves A, Stone HA, Weitz DA (2007b) Dripping to jetting transitions in coflowing liquid streams. Phys Rev Lett 99:094502

Whitesides GM (2006) The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature 442:368–373

Whitesides GM (2013) Cool, or simple and cheap? Why not both? Lab Chip 13:11–13

Whitesides G (2014) The lab finally comes to the chip! Lab Chip 14:3125–3126

Xu QB, Hashimoto M, Dang TT, Hoare T, Kohane DS, Whitesides GM, Langer R, Anderson DG (2009) Preparation of monodisperse biodegradable polymer microparticles using a microfluidic flow-focusing device for controlled drug delivery. Small 5:1575–1581

Yang H, Luk VN, Abelgawad M, Barbulovic-Nad I, Wheeler AR (2008) A world-to-chip interface for digital microfluidics. Anal Chem 81:1061–1067

Yashina A, Meldrum F, deMello A (2012) Calcium carbonate polymorph control using droplet-based microfluidics. Biomicrofluidics 6:22001–2200110

Yetisen AK, Akram MS, Lowe CR (2013) Paper-based microfluidic point-of-care diagnostic devices. Lab Chip 13:2210–2251

Zhang Y, Ho Y-P, Chiu Y-L, Chan HF, Chlebina B, Schuhmann T, You L, Leong KW (2013) A programmable microenvironment for cellular studies via microfluidics-generated double emulsions. Biomaterials 34:4564–4572

Zheng WF, Wang Z, Zhang W, Jiang XY (2010) A simple pdms-based microfluidic channel design that removes bubbles for long-term on-chip culture of mammalian cells. Lab Chip 10:2906–2910

Zhou H, Yao Y, Chen Q, Li G, Yao S (2013) A facile microfluidic strategy for measuring interfacial tension. Appl Phys Lett 103:234102

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Leadership Fellowship (FCM, LAB, CSM and XG, EP/H005374/1) and EPSRC Grant Number EP/I001514/1, where this program Grant funds the Materials in Biology (MIB) consortium (FCM and WJM). The authors thank Matthew Broadbent and Graham Brown for machining the end caps. MAL would like to thank the Whitaker International Program of the Institute of International Education and the US–UK Fulbright Commission for personal financial support during this research period.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Data availability: The data associated with this paper are openly available from the University of Leeds data repository. http://doi.org/10.5518/71.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 4 (WMV 806 kb)

Supplementary material 5 (WMV 1056 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Levenstein, M.A., Bawazer, L.A., Mc Nally, C.S. et al. A reproducible approach to the assembly of microcapillaries for double emulsion production. Microfluid Nanofluid 20, 143 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10404-016-1806-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10404-016-1806-2