Abstract

RNAi interference (RNAi) for insect pest control is often used to silence genes controlling vital functions, thus generating lethal phenotypes. Here, we propose a novel approach, based on the knockout of an immune gene by dsRNA-expressing bacteria as a strategy to enhance the impact of spray applications of the entomopathogen Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt). The target gene, Sl 102, controls the encapsulation and nodulation responses in the noctuid moth Spodoptera littoralis (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). To deliver Sl 102 dsRNA, we have developed a bacterial expression system, using HT115 Escherichia coli. This allows a much cheaper production of dsRNA and its protection against degradation. Transformed bacteria (dsRNA-Bac) administered through artificial diet proved to be more effective than dsRNA synthesized in vitro, both in terms of gene silencing and immunosuppression. This is a likely consequence of reduced dsRNA environmental degradation and of its protected release in the harsh conditions of the gut. The combined oral administration with artificial diet of dsRNA-Bac and of a Bt-based biopesticide (Xentari™) resulted in a remarkable enhancement of Bt killing activity, both on 4th and 5th instar larvae of S. littoralis, either when the two components were simultaneously administered or when gene silencing was obtained before Bt exposure. These results pave the way toward the development of novel Bt spray formulations containing killed dsRNA-Bac, which synergize Bt toxins by suppressing the insect immune response. This strategy will preserve the long-term efficacy of Bt-based products and can, in principle, enhance the ecological services provided by insect natural antagonists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key message

-

RNAi for insect control requires the development of effective delivery strategies of dsRNA.

-

Bacteria expressing a dsRNA targeting an immune gene induce its silencing when ingested by larvae of the noctuid moth Spodoptera littoralis.

-

The resulting immunosuppression enhances the killing activity of a Bt-based biopesticide.

-

These immune suppressive bacteria can be used as synergistic factors to develop more effective Bt sprays, and to preserve Bt efficacy.

Introduction

RNAi interference (RNAi), the sequence specific gene silencing mediated by short non-coding dsRNA, that promotes mRNA cleavage or repression of mRNA translation was first discovered by Fire et al. (1998) in their pioneering study on the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Since then, RNAi has been reported in almost all eukaryotes as a fine-tuned mechanism of gene regulation (Carthew and Sontheimer 2009; Gebert and MacRae 2019) and as an important component of antiviral defense barriers (Ding 2010; Bronkhorst and van Rij 2014; Ding et al. 2018). More recent studies have revealed an unexpected and intense movement of regulative dsRNAs even between organisms (Knip et al. 2014). This fascinating phenomenon, called “cross-kingdom RNAi,” in some cases contributes to the communication between plant or animal hosts and associated pathogens, parasites or symbiotic microorganisms (Knip et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2015, 2017; Weiberg et al. 2015).

The RNAi pathway has been largely exploited as a potent loss-of-function tool to unravel gene functions in animals (Housden et al. 2017), including insects (Di Lelio et al. 2014; Sugahara et al. 2015; Li et al. 2017, 2018; Jia et al. 2018; Pan et al. 2018). Interestingly, in insects the oral ingestion of dsRNA can trigger a silencing response in most body tissues (i.e., systemic RNAi), which can be profitably exploited for the development of RNAi-based control strategies against agricultural pests and pathogen vectors, by selectively targeting genes controlling physiological and developmental pathways of vital importance (Joga et al. 2016; Cooper et al. 2019). RNAi-plants to control coleopteran pests have recently reached the market (Zotti et al. 2018) and, along with other RNAi-based biopesticides, are expected to become an effective alternative to chemical products.

Systemic RNAi is robust in Coleoptera, absent in Diptera and unevenly present in other insect orders (Joga et al. 2016; Cooper et al. 2019), such as in Lepidoptera, where occurs in several noctuid species (e.g., Helicoverpa and Spodoptera spp.) (Tian et al. 2009; Di Lelio et al. 2014; Lim et al. 2016; Cooper et al. 2019). This paves the way toward the development of RNAi-based pest control strategies, which, however, can be profitably pursued if effective oral delivery methods, to overcome environmental and insect gut degradation of dsRNA molecules, are developed (Yu et al. 2013; Joga et al. 2016; Cooper et al. 2019). Polymers currently being used as carriers for oral delivery of dsRNA molecules in Lepidoptera (He et al. 2013; Christiaens et al. 2018) are comparatively less effective than plants and bacteria (Zhang et al. 2017; Zotti et al. 2018). The idea of using bacteria as delivery vectors of dsRNA molecules was first proposed in the pioneering studies on RNAi in the bacteriophagous nematode C. elegans (Timmons and Fire 1998; Timmons et al. 2001). This proof of concept prompted studies on the exploitation of the bacterial delivery strategy for pest control purposes, in order to overcome the technical and economic problems associated with the use of dsRNA synthesized in vitro. Tian et al. (2009) first reported the efficacy of bacterially expressed dsRNA in the induction of systemic RNAi in insects, in particular in the lepidopteran pest Spodoptera exigua. Several other studies have clearly shown that bacterial delivery (1) is cost-effective, (2) protects dsRNA molecules against degradation and (3) allows the development of new plant protection products/tools (Kim et al. 2015; Lim et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2016; Ganbaatar et al. 2017; Israni and Rajam 2017; Vatanparast and Kim 2017; Wang et al. 2018).

We have recently shown that RNAi-mediated silencing of an immune gene in S. littoralis larvae, obtained by oral microinjection of dsRNA synthesized in vitro, results in a significant enhancement of insect mortality triggered by Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) (Caccia et al. 2016; Di Lelio et al. 2019). This evidence sheds light on Bt killing mechanism (Caccia et al. 2016; Di Lelio et al. 2019) and paves the way toward the development of novel pest control strategies based on immunosuppression as a tool to enhance the impact of entomopathogens. Here, we contribute to this goal by exploring the use of bacteria as delivery vectors of dsRNAs targeting the immune system, in order to enhance the insecticidal activity of commercially available Bt-based biopesticides.

Materials and methods

Insect rearing

Spodoptera littoralis larvae were reared on artificial diet (41.4 g/l wheat germ, 59.2 g/l brewer’s yeast, 165 g/l corn meal, 5.9 g/l ascorbic acid, 1.53 g/l benzoic acid, 1.8 g/l methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate and 29.6 g/l agar), at 25 ± 1 °C and 70 ± 5% RH, with 16:8 h light–dark period.

In vitro synthesis of Sl 102 dsRNA

Total RNA was extracted from haemocytes of S. littoralis 6th instar larvae, retro-transcribed with the Ambion® RETROscript® Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and a 580 bp long Sl 102 cDNA fragment was obtained by PCR (Sl 102 F primer: TACATCCAAGTAAATTTGCAAGGC; Sl 102 R primer: GGCCCAGAACATTCTCACCTC). This cDNA fragment was used as template for a nested PCR reaction, performed with primers containing at their 5′ ends the T7 polymerase promoter sequence (T7-Sl 102 F: TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAACCTCCTGAGCGTGCCTGA; T7-Sl 102 R: TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGGAGTGCTGCTTCAGAATCAT). The resulting PCR product served as template to synthesize a dsRNA (469 bp long), using the Ambion® MEGAscript® RNAi Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Synthesized dsRNA was quantified by measuring its absorbance at 260 nm with a Varioskan Flash Multimode Reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and purity was evaluated by assessing 260/280 nm absorbance ratios. dsRNA was run on 1% agarose gels to check its integrity.

A GFP dsRNA, used in control experiments, was similarly produced starting from the cloning vector pcDNA® 3.1/CT-GFP TOPO® (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which was used as template for a PCR reaction, performed with primers containing at their 5′ ends the T7 polymerase promoter sequence (T7-GFP F: TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGTGGAGAGGGTGAAGGTG; T7-GFP R: TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGGGCAGATTGTGTCGACAG). The resulting PCR product served as template to synthesize a dsRNA (531 bp long), as described above.

Production of transformed HT115 Escherichia coli expressing Sl 102 dsRNA

A L4440 recombinant vector, encoding Sl 102 or GFP (negative control) dsRNA molecules, was produced with the Gateway® cloning technology and used to transform HT115 E. coli cells.

Cloning of Sl 102 and transformation of bacteria for Sl 102 dsRNA production

Total RNA extracted from S. littoralis haemocytes was subjected to retro-transcription (Ambion® RETROscript® Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and, then, used for PCR amplification of Sl 102, with specific primers (Sl 102 F: CACCAACCTCCTGAGCGTGCCT; Sl 102 R: CGGAGTGCTGCTTCAGAATC). A GFP fragment, used in control experiments, was amplified from the cloning vector pcDNA® 3.1/CT-GFP TOPO® (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which served as template for a PCR reaction, using specific primers (GFP F: CACCAGTGGAGAGGGTGAAGGTG; GFP R: GGGCAGATTGTGTCGACAG).

PCR products were ligated into the pENTR/D®-TOPO® vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific), compatible with the Gateway® technology, and the vector was introduced into chemically competent One Shot® TOP10 E. coli cells that were plated on LB agar. Plasmids from colonies grown overnight were extracted (Charge-Switch-Pro plasmid miniprep kit, Thermo Fisher) and sequenced. Sl 102 and GFP fragments were cloned into a Gateway®-compatible L4440 vector, constructed by using the Gateway® vector conversion system, ligating a blunt-ended cassette containing attR sites flanking the ccdB gene and the chloramphenicol resistance gene. Cloning was performed using a transposition reaction catalyzed by the LR clonase® enzyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

The resulting recombinant plasmids were introduced into competent E. coli HT115 cells that lack RNase III and can be induced to express T7 polymerase in the presence of isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Newmark et al. 2003; Timmons et al. 2001; Timmons and Fire 1998).

To produce dsRNA, the transformed bacteria were grown in the liquid broth Luria–Bertani (LB), containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 12.5 μg/ml tetracycline, at 37 °C for 16 h, under continuous shaking (250 rpm). Then, 5 ml of cultured broth was added to 500 ml of fresh LB medium and allowed to grow until OD600 = 0.6–0.7. Expression of T7 RNA polymerase gene, for dsRNA overexpression, was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG to transformed bacteria, which were incubated overnight at 37 °C, under continuous shaking. Bacteria producing dsRNA targeting Sl 102 gene or producing GFP dsRNA are hereafter denoted as Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac and GFP dsRNA-Bac, respectively.

Bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation at 12,000×g for 1 min at 4 °C and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 1.4 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4). To kill the bacteria to be used in all feeding bioassays and to facilitate the release of dsRNA, a sonication protocol was developed. Bacterial suspensions were subjected to an increasing number of sonication cycles on ice with an ultrasound homogeniser (Sonoplus, Bandelin), adopting decreasing time intervals between cycles. The bacteria viability after the treatments was evaluated by plating the resulting sonicated suspension on Petri dishes containing LB agar (supplied with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 12.5 μg/ml tetracycline). Complete mortality was obtained with ten cycles of sonication (59 s on/2 s off, 95% amplitude).

qRT-PCR absolute quantification of Sl 102 dsRNA produced by bacteria

dsRNA produced by E. coli was extracted from cell pellets, using the protocol by Timmons et al. (2001). The quantification was performed by quantitative real-time PCR using Applied Biosystems™ SYBR™ Green master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The quantity of dsRNA was determined by relating its threshold value (CT) values to an established standard curve, according to the absolute quantification method (Rutledge and Côté 2003).The standard curve for Sl 102 dsRNA was established by plotting the logarithm of 6 10-fold dilutions of a starting solution containing 300 ng/µl of L4440 Gateway® vector with insert, against the corresponding CT value. The PCR efficiency (E = 98.274%) was calculated on the base of the slope and the coefficient of correlation (R2) of the standard curve (slope = − 3.365, y intercept = 13.540, R2 = 0.997), according to the following formula: E = 10(−1/slope) − 1. The standard curve for GFP dsRNA was similarly established, by plotting the logarithm of 6 10-fold dilutions of a starting solution containing 200 ng/µl of L4440 Gateway® vector with insert, against the corresponding CT. The PCR efficiency (E = 104.0477%) was calculated on the base of the slope and the correlation coefficient (R2) of the standard curve (slope = − 3.229, y intercept = 17.650, R2 = 0.984), according to the following formula: E = 10(−1/slope) − 1.

All primer pairs were designed using Primer Express 3.0 software (Life Technologies), following the standard procedure. Negative controls (water) were included in each run of the qRT-PCR.

Oral administration of dsRNA to Spodoptera littoralis larvae

To assess the efficiency of dsRNA delivery through the use of sonicated bacteria, S. littoralis larvae were orally treated with Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac, using two different protocols. In a first set of experiments, dsRNA-Bac was delivered by gavage with a microsyringe, as previously described (Di Lelio et al. 2014; Caccia et al. 2016). Briefly, newly molted S. littoralis 4th instar larvae were anaesthetized on ice and 1 µl of Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac (GFP dsRNA-Bac in controls) solution (corresponding to 45 ng of dsRNA) was poured into the lumen of the foregut by means of a Hamilton Microliter syringe (1701RNR 10 µl, gauge 26 s, length 55 mm, needle 3). This treatment was repeated three times, at 24 h intervals. A group of larvae that received 1 µl of a solution of Sl 102 dsRNA (45 ng/µl) synthesized in vitro (or GFP dsRNA in controls) acted as positive control, since this dose proved to be effective in the induction of gene silencing (Di Lelio et al. 2014).

The second protocol was developed for feeding bioassays on artificial diet. Newly molted 4th instar larvae were isolated in multi-well plastic trays (Bio-Rt-32, Frontier Agricultural Sciences), containing artificial diet, covered with perforated plastic lids (Bio-Cv-4, Frontier Agricultural Sciences), and maintained under the rearing conditions reported above. The experimental larvae, for 3 consecutive days, at 24 h intervals, were offered a small piece of diet with the upper surface (0.25 cm2) uniformly overlaid with 1 μl of a solution of Sl 102 dsRNA synthesized in vitro (45 ng/µl) or a Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac suspension containing 45, 100 and 200 ng of dsRNA. Controls received GFP dsRNA synthesized in vitro or GFP dsRNA-Bac. Experimental larvae were maintained on artificial diet before and after the 3 administrations of dsRNA synthesized in vitro or of dsRNA-Bac suspension, which were overlaid on a small amount of the same diet, which was completely consumed in about 1 h.

Silencing efficiency was evaluated by qRT-PCR, as described below, 24 h after the last dsRNA administration, and the impact on immune competence was assessed by measuring the encapsulation index of injected chromatography beads, as previously described (Di Lelio et al. 2014).

qRT-PCR relative quantification of Sl 102 transcription

Total RNA was extracted from haemocytes of S. littoralis larvae, using TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Gene transcription level was assessed by qRT-PCR, which was carried out by using Sl 102 gene-specific primers (Sl 102 RT F: GGCGGTGTCGTCGTCGATTATG; Sl 102 RT R: GAGCGAGGAAATGTTCAAT), designed to detect a segment of the Sl 102 mRNA external to the segment targeted by the dsRNA. S. littoralisβ-actin gene (Accession Number Z46873) was used as endogenous control for RNA loading (β-actin RT F: CGTCTTCCCATCCATCGT; β-actin RT R: CCTTCTGACCCATACCAACCA). All primers were designed using Primer Express, version 1.0 software (Applied Biosystems). The level of mRNA was measured by one-step qRT-PCR using the Applied Biosystems™ SYBR™ Green master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The amount of the target transcript relative to the endogenous control was determined using the 2-ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001; Pfaffl 2001; Pfaffl et al. 2002). For validation of the ΔΔCT method, the difference between the CT value of Sl 102 and the CT value of β-Actin transcripts [ΔCT = CT (Sl 102) − CT (β-actin)] was plotted versus the log of 10-fold serial dilutions (5000, 500, 50, 5 and 0.5 ng) of the purified RNA samples. The plot of log total RNA input versus ΔCT displayed a slope less than 0.1 (slope = 0.0154, R2 = 0.0776), indicating that the efficiencies of the 2 amplicons were approximately equal.

Bioassays with Xentari™

Three different feeding bioassays on S. littoralis larvae were carried out, in order to evaluate the impact of Sl 102 gene silencing on the killing activity of the entomopathogen Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt). Preliminary trials were performed in order to identify sublethal Bt doses (i.e., with no or very low effect on mortality and only moderately affecting the speed of larval development), which were 9 μg/cm2 and 12 μg/cm2 for 4th and 5th instar larvae, respectively. The use of this Bt dose allowed the assessment of any increase in the mortality rate caused by the RNAi-induced immunosuppression.

In the first type of bioassay (sequential treatment), 4th instar larvae were fed for 3 days with artificial diet overlaid with Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac (or GFP dsRNA-Bac) (corresponding to 200 ng of dsRNA), as described above. Four hours after the administration of the last dsRNA dose, the experimental larvae, which in the meantime attained the 5th instar, were fed with artificial diet overlaid with a dose of 12 μg/cm2 of Xentari™ (Valent BioSciences), a bioinsecticide based on Bt subsp. aizawaii, containing several Cry toxins (Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, Cry1Ca, Cry1 Da and Cry2Ab). This treatment with Xentari™ was repeated 3 times, at 24 h interval, and, since Xentari™ was suspended in water, control diet was overlaid with water.

A second bioassay was designed to evaluate the effect of the simultaneous administration of dsRNA and Xentari™, to better simulate field spraying with a product containing both components. Newly molted 4th instar larvae were fed with artificial diet overlaid with Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac (or GFP dsRNA-Bac) (corresponding to 200 ng of dsRNA), as previously described, and, after 4 h, Xentari™ was administered at a dose of 9 μg/cm2. This was done for 3 days. Controls were treated with water. The same experiment was performed with newly molted 5th instar larvae, using a dose of Xentari™ of 12 μg/cm2. Mortality was daily recorded for 8 days, when the experimental larvae were weighed.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism, version 6.0b. Encapsulation assay and Sl 102 gene expression in gavage experiments were analyzed using the unpaired Student’s t test, and larval weight was analyzed using One-Way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple-comparison post hoc test. When ANOVA assumptions were not fulfilled, nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons post hoc test was used. Sl 102 gene expression in feeding experiments was analyzed using Three-Way ANOVA to assess the effect of dsRNA treatment, production protocol and concentration. Levene’s test was used to test the homogeneity of variance. When necessary, transformation of data was carried out to meet the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity. When significant effects were observed (P < 0.05), the Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used to compare mean values. Survival curves of S. littoralis larvae were compared using Kaplan–Meier and log-rank analyses. Normality of data was checked with Shapiro–Wilk test and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, while homoscedasticity was tested with Levene’s test and Bartlett’s test.

Results

Production of bacteria expressing Sl 102 dsRNA

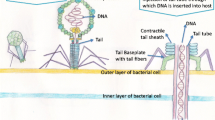

To produce bacteria expressing dsRNA, a partial sequence of Sl 102 gene (or GFP in controls) was inserted into L4440 vector, using the rapid and highly efficient Gateway® recombinational cloning system (Landy 1989). Briefly, the PCR product of the fragment of interest (Sl 102 or GFP as control) was inserted in a donor vector to create the attL-containing entry clone. This latter has been used in a second recombination reaction with an attR-destination vector (L4440 vector properly converted into a Gateway® destination vector), to create an attB-containing expression clone used to transform HT115 E. coli cells (see Fig. 1a). Production of dsRNA occurs thanks to attB site-specific attachment sites on E. coli chromosome, and dsRNA overexpression, under the T7 promoters, is induced by IPTG addition. The amount of the dsRNA produced by bacteria (Fig. 1b) has been quantified by absolute qRT-PCR (Fig. 1c).

Production of HT115 Escherichia coli cells expressing dsRNA. a Cloning and transformation protocol. b Expression of dsRNA by transformed HT115 E. coli; total RNA samples were subjected to RT-PCR, and amplicons were resolved on 1% agarose gel. Primers specific for Sl 102 or GFP genes produced amplicons of the expected size in HT115 E. coli expressing Sl 102 dsRNA or GFP dsRNA, respectively (lanes 1 and 2), whereas the same primers did not generate any amplicon when total RNA from non transformed bacteria was used (wt HT115) (lanes 3 and 4). c Calibration curves used for qRT-PCR absolute quantification of Sl 102 and GFP dsRNA present in E. coli suspensions used in the bioassays

Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac produced were sonicated in order to disrupt the cell wall and to facilitate the release of dsRNA in the insect gut. Moreover, the use of killed bacteria is an essential requirement for their safe release in the environment.

Silencing efficiency and immune suppressive effects of Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac

We first assessed RNAi efficiency and associated immunosuppression of Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac by comparing their silencing effect with that induced by Sl 102 dsRNA synthesized in vitro, adopting a protocol previously described (Di Lelio et al. 2014). Thus, Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac and Sl 102 dsRNA produced in vitro (hereafter denoted as Sl 102 dsRNA-synt) (GFP dsRNA-Bac and GFP dsRNA-synt were used as controls, respectively) were orally administered, for 3 days to 4th instar S. littoralis larvae, by gavage with a microsyringe. Since 45 ng/µl is the lowest dose of Sl 102 dsRNA-synt inducing maximal down-regulation of Sl 102 gene (Di Lelio et al. 2014), an equal amount of dsRNA, measured by absolute qRT-PCR quantification (Fig. 1c), was administered as Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac.

This experiment demonstrated that both dsRNA-synt and Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac are associated with a significant level of silencing of the target gene compared to controls (Student’s t test: for dsRNA-synt t = 18.282, df = 28, P < 0.0001, for dsRNA-Bac t = 16.621, df = 28, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2), even though dsRNA-synt was by far more active than dsRNA-Bac. Since Sl 102 gene is involved both in the nodulation of microorganisms and in the encapsulation of large parasites (e.g., parasitoid eggs, nematodes) (Falabella et al. 2012; Di Lelio et al. 2014; Caccia et al. 2016), which are immune reactions sharing functional similarities (Lavine and Strand 2002), we used the encapsulation response against chromatography beads as a measure of immune suppression induced by Sl 102 silencing. Indeed, gene knockout was associated with a significant impairment of encapsulation response by haemocytes of silenced larvae, for both types of dsRNAs (Student’s t test: for dsRNA-synt t = 118.64, df = 28, P < 0.0001, for dsRNA-Bac t = 63.508, df = 28, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3).

Transcript levels of Sl 102 gene in S. littoralis 4th instar larvae orally treated for 3 days with dsRNA. The Sl 102 gene was down-regulated upon ingestion of Sl 102 dsRNA administered by oral gavage, both in the case of dsRNA synthesized in vitro (Sl 102 dsRNA-synt) and suspensions of sonicated bacteria expressing Sl 102 dsRNA (Sl 102 dsRNA-bac). Delivery with artificial diet showed a silencing response that was dose-dependent and more pronounced when bacteria were used as delivery vectors. GFP dsRNA synthesized in vitro and bacteria expressing GFP dsRNA were used in control experiments. The values reported are the mean ± standard errors (*P < 0.0001, Student’s t test)

Encapsulation assay in S. littoralis 4th larvae treated for 3 days with Sl 102 dsRNA synthesized in vitro (Sl 102 dsRNA-synt) or transformed HT115 E. coli expressing Sl 102 dsRNA (Sl 102 dsRNA-bac). Chromatography beads injected into the body cavity of control larvae were encapsulated and melanized (a). On the contrary, the efficiency of encapsulation was lower in silenced larvae, independently from the dsRNA administration method (gavage or with artificial diet) (b). The encapsulation index was affected by oral delivery method and, in the case of oral administration on artificial diet, by dsRNA quantity. GFP dsRNA synthesized in vitro and bacteria expressing GFP dsRNA were used in control experiments. The values reported are the mean ± standard errors (*P < 0.0001, Student’s t test)

To explore whether the bacterial delivery of dsRNA confers protection against degradation, Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac and Sl 102 dsRNA-synt were overlaid on artificial diet and separately offered to S. littoralis larvae, in order to compare their silencing efficiency and immune suppressive activity, at different experimental doses. The transcription level of the target gene was significantly affected by the dsRNA treatment (Three-Way ANOVA: F1,140 = 567.493; P < 0.0001), exhibited a more pronounced down-regulation when dsRNA-Bac was used (Three-Way ANOVA: F1,140 = 152.170; P < 0.0001) and was positively correlated with the experimental dose used (Three-Way ANOVA: F2,140 = 49,155; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). The encapsulation reaction showed a similar pattern of variation (Three-Way ANOVA: dsRNA treatment F1,124 = 1350,724, P < 0.0001; dsRNA production F1,124 = 27.604, P < 0.0001; dsRNA dose F2,124 = 26.472, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3).

Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac enhance the killing activity of Bacillus thuringiensis

The induction of effective immune suppressive RNAi by Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac prompted us to assess their potential in enhancing the efficacy of a Bt-based biopesticide (Xentari™).

In a first set of experiments (sequential treatments), 4th instar S. littoralis larvae were fed with artificial diet overlaid with Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac for 3 days, as described above for gavage experiments. Four hours after the last dsRNA treatment, Xentari™ was administered to larvae with the artificial diet for 3 subsequent days. Xentari™ induced a significantly higher mortality only in larvae fed with Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac (log-rank test: Chi-square = 172.3, df = 3, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4a) and determined a significant weight reduction in the surviving larvae (Kruskal–Wallis: KW = 95.08; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4b), which completely failed to pupate.

Bioassay with S. littoralis 4th instar larvae exposed to dsRNA before Bt treatment. Newly molted larvae were treated for 3 days with artificial diet layered with transformed HT115 E. coli expressing Sl 102 dsRNA (Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac, corresponding to 200 ng of dsRNA) and then with 12 µg/cm2 of Xentari™ for 3 more days (see “Materials and methods” section for experimental details). Survival was monitored until day 8 (a), when the weight was assessed on the surviving experimental larvae (b). Bacteria expressing GFP dsRNA were used in control experiments. The timing of the treatments is indicated with arrows. The values reported are the mean ± standard errors (in a *P < 0.0001 based on log-rank test; in b different letters denote statistical difference based on Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparison post hoc test)

A second set of experiments was performed to test the efficacy of the simultaneous administration of Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac and Xentari™. This experiment was designed to reproduce more closely the possible effects of a field application of both active ingredients (dsRNA and Bt). The results obtained, both with 4th and 5th instar larvae, clearly showed that simultaneous administration of Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac and Xentari™ caused a significantly higher mortality in Sl 102-silenced larvae compared to controls (Figs. 5a, 6a) (log-rank test 4th instar larvae: Chi-square = 49.02; df = 3; P < 0.0001; log-rank test 5th instar larvae: Chi-square = 156.6; df = 3; P < 0.0001) and had a significant impact on body weight both of 4th instar (Kruskal–Wallis: KW = 65.96; P < 0.0001) and 5th instar larvae (Kruskal–Wallis: KW = 135.1; P < 0.0001) (Figs. 5b, 6b), which completely failed to pupate.

Bioassay with S. littoralis 4th instar larvae simultaneously exposed to dsRNA and Bt. Newly molted larvae were treated for 3 days with artificial diet layered with transformed HT115 E. coli expressing Sl 102 dsRNA (Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac, corresponding to 200 ng of dsRNA) and with 9 µg/cm2 of Xentari (see “Materials and methods” section for experimental details). Survival was monitored until day 8 (a) when the weight was assessed on the surviving experimental larvae (b). Bacteria expressing GFP dsRNA were used in control experiments. The timing of the treatments is indicated by arrows The values reported are the mean ± standard errors (in a **P < 0.0001 and *P < 0.0046 based on log-rank test; in b different letters denote statistical difference based on Kruskal–Wallis, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons post hoc test)

Bioassays with S. littoralis 5th instar larvae simultaneously exposed to dsRNA and Bt. Newly molted larvae were treated for 3 days with artificial diet layered with transformed HT115 E. coli expressing Sl 102 dsRNA (Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac, corresponding to 200 ng of dsRNA) and with 12 µg/cm2 of Xentari (see “Materials and methods” section for experimental details). Survival was monitored until day 8 (a), when the weight was assessed on the surviving experimental larvae (b). Bacteria expressing GFP dsRNA were used in control experiments. The timing of the treatments is indicated by arrows. The values reported are the mean ± standard errors (in a *P < 0.0001 based on log-rank test; in b different letters denote statistical difference based on Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparison post hoc test)

Discussion

RNAi-based control strategies of insect pests offer new opportunities for the development of sustainable Integrated Pest Management plans, due to their specificity and reduced or null effect on nontarget species. This potential has been already unlocked by the recent introduction on the market in North America of genetically manipulated maize plants, which express dsRNA targeting the coleopteran species Diabrotica virgifera (Zotti et al. 2018). The development of this novel plant protection tool has been undoubtedly favoured by the high RNAi efficiency in Coleoptera. It would be desirable to further expand the reach of this insect control strategy by hitting pest species in other insect orders of remarkable economic importance, such as Lepidoptera. Although efficiency of RNAi response in Lepidoptera varies among species and depends on the efficiency of the delivery method, Helicoverpa and Spodoptera spp. have proved to be quite susceptible to orally administered dsRNA, which may trigger a systemic RNAi response (Tian et al. 2009; Di Lelio et al. 2014; Lim et al. 2016; Cooper et al. 2019).

In a previous study, we have shown that immune impairment of S. littoralis larvae, induced by oral administration of dsRNA molecules, causes an increase of susceptibility to the entomopathogen B. thuringiensis and accounts for the key importance of septicaemia in the killing activity of this biocontrol agent (Caccia et al. 2016). This proof of concept allows the development of novel pest control strategies aiming to enhance the impact of entomopathogens by RNAi-mediated silencing of immune genes. However, to pursue this goal, it is essential to develop RNAi delivery strategies for field applications, which are efficient, safe and economically sustainable. In the present study, we have explored the use of bacteria as potential delivery vectors of dsRNA targeting insect immune genes and evaluated their impact on the efficacy of a Bt-based commercial product (Xentari™) used for Spodoptera spp. control.

We produced dsRNA-expressing E. coli bacteria, taking advantage of the Gateway® recombinational cloning system (Hartley et al. 2000; Walhout et al. 2000; Reboul et al. 2001).

The Gateway® technology allowed us the transformation of E. coli cells by a simple two-step method that exploits specific vectors and recombination enzymes. This standardized and high-fidelity method proved to be time-saving and convenient for our purposes and may represent the approach of choice for the production of large amounts of dsRNA and large-scale screenings of RNAi targets.

Bacteria expressing Sl 102 dsRNA were effective in silencing the target gene, even though to a reduced extent compared to dsRNA-synt, and in the induction of immunosuppression when injected directly into the oral cavity of S. littoralis larvae (gavage); in contrast, it is of interest to note that Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac showed a higher efficacy, compared to Sl 102 dsRNA-synt, when orally administered with artificial diet (Figs. 2, 3). The level of RNAi-induced gene silencing by Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac, along with the alteration of the encapsulation response by haemocytes, showed a clear dose-dependent response. Comparatively, naked dsRNA synthesized in vitro was less effective when administered with the feeding substrate. Indeed, at all experimental doses considered, the decrease of the transcript level and the encapsulation index induced by dsRNA-synt were always less evident than those observed upon ingestion of Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac. This evidence further corroborates previous reports indicating that the bacterial envelope protects dsRNA molecules against degradation (both environmental and inside the insect gut) and likely allows a more prolonged presence/release of dsRNA (Yang and Han 2014; Kim et al. 2015; Lim et al. 2016; Vatanparast and Kim 2017).

The oral efficiency of bacterial-delivered dsRNA targeting Sl 102 gene prompted us to assess their use for enhancing the virulence of entomopathogens. Our results clearly demonstrate that the immunosuppression induced by Sl 102 dsRNA-Bac strongly synergizes Bt-based bioinsecticides. Indeed, these bacterial cells administered with the feeding substrate to S. littoralis larvae were able to enhance the mortality induced by Bt, regardless of previous or simultaneous administration of dsRNA and of the experimental larval stage treated. However, Bt exposure of larvae already showing gene silencing seems to have an impact on mortality slightly higher than that observed in response to concurrent administration of dsRNA and Bt, whichever is the instar treated. Indeed, the already-established immunosuppression likely favors a more rapid spread of bacterial septicaemia.

Bt sprays used to control lepidopteran larvae contain mixtures of Cry1A and Cry2A toxins, since they are based on spores and crystals produced by the kurstaki and aizawaii strains (Lacey et al. 2015). The toxin miscellaneous in these formulations retards but cannot avoid the development of resistance under strong selective pressure in the field (Lacey et al. 2015; Peralta and Palma 2017). Moreover, a major concern threatening their use is generated by the decrease in the efficacy of Bt sprays on mature larvae and as a consequence of reiterated exposure to Bt toxins of species with multiple generations across the growing season (Navon 2000; Janmaat and Myers 2003; Cory 2017). To alleviate these problems, several molecules able to improve Bt efficacy have been found (e.g., proteins that improve toxin production by the bacteria and agents that enhance permeability of the peritrophic matrix and facilitate toxin accumulation near the binding sites) (Xu et al. 2001; Mohan et al. 2008; Fang et al. 2009) and included in Bt formulations to enhance their efficacy. Our results further contribute to the goal of enhancing the impact and the long-term efficacy of Bt spray formulations, by impairing the immune response of the insect, which is essential in counteracting the septicaemia induced by Bt toxins.

Here, we demonstrate that the insecticide activity of B. thuringiensis, one of the most widely used biopesticides, can be enhanced modulating the immune competence of the target pest. From a theoretical point of view, the induction of a reduced immune competence in the target pest appears to be ecologically more sustainable as it can enhance the ecological services provided by natural antagonists. Indeed, such an approach will promote the establishment and proliferation of biological control agents, rather than favoring their dispersal as a consequence of a treatment directly killing the target pest and reducing its density.

In conclusion, the oral delivery of Sl 102 dsRNA-bac to S. littoralis larvae along with the food triggers a systemic RNAi response and a consistent immune suppression. Thus, immune suppressive dsRNAs vectored by bacteria may be exploited as synergistic factors in novel Bt sprays and to preserve the insecticidal activity of B. thuringiensis.

Author contributions

SC and FP conceived and designed research. FA, EB, SC, IDL and PV performed experiments. EB, IDL and SC analyzed data. SC and FP wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

References

Bronkhorst AW, van Rij RP (2014) The long and short of antiviral defense: small RNA-based immunity in insects. Curr Opin Virol 7:19–28

Caccia S, Di Lelio I, La Storia A, Marinelli A, Varricchio P, Franzetti E, Banyuls N, Tettamanti G, Casartelli M, Giordana B, Ferré J, Gigliotti S, Ercolini D, Pennacchio F (2016) Midgut microbiota and host immunocompetence underlie Bacillus thuringiensis killing mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:9486–9491

Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ (2009) Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 136:642–655

Christiaens O, Tardajos MG, Martinez Reyna ZL, Dash M, Dubruel P, Smagghe G (2018) Increased RNAi efficacy in Spodoptera exigua via the formulation of dsRNA with guanylated polymers. Front Physiol 9:316. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00316

Cooper AMW, Silver K, Zhang J, Parka Y, Zhu KY (2019) Molecular mechanisms influencing efficiency of RNA interference in insects. Pest Manag Sci 75:18–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.5126

Cory (2017) Evolution of host resistance to insect pathogens. Curr Opin Insect Sci 21:54–59

Di Lelio I, Varricchio P, Di Prisco G, Marinelli A, Lasco V, Caccia S, Casartelli M, Giordana B, Rao R, Gigliotti S, Pennacchio F (2014) Functional analysis of an immune gene of Spodoptera littoralis by RNAi. J Insect Physiol 64:90–97

Di Lelio I, Illiano A, Astarita F, Gianfranceschi L, Horner D, Varricchio P, Amoresano A, Pucci P, Pennacchio F, Caccia S (2019) Evolution of an insect immune barrier through horizontal gene transfer mediated by a parasitic wasp. PLoS Genet 15(3):e1007998. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1007998

Ding SW (2010) RNA-based antiviral immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 10:632–644

Ding SW, Han Q, Wang J, Li WX (2018) Antiviral RNA interference in mammals. Curr Opin Immunol 54:109–114

Falabella P, Riviello L, Pascale M, Di Lelio I, Tettamanti G, Grimaldi A, Iannone C, Monti M, Pucci P, Tamburro AM, Deeguileor M, Gigliotti S, Pennacchio F (2012) Functional amyloids in insect immune response. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 42:203–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.11.011

Fang S, Wang L, Guo W, Zhang X, Peng D, Luo C, Yu Z, Sun M (2009) Bacillus thuringiensis Bel protein enhances the toxicity of Cry1Ac protein to Helicoverpa armigera larvae by degrading insect intestinal mucin. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:5237–5243. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00532-09

Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC (1998) Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391:806–811

Ganbaatar O, Cao B, Zhang Y, Bao D, Bao W, Wuriyanghan H (2017) Knockdown of Mythimna separata chitinase genes via bacterial expression and oral delivery of RNAi effectors. BMC Biotechnol 17:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12896-017-0328-7

Gebert LFR, MacRae IJ (2019) Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell 20:21–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-018-0045-7

Hartley JL, Temple GF, Brasch MA (2000) DNA cloning using in vitro site specific recombination. Genome Res 10:1788–1795

He B, Chu Y, Yin M, Müllen K, An C, Shen J (2013) Fluorescent nanoparticle delivered dsRNA toward genetic control of insect pests. Adv Mater 25:4580–4584

Housden BE, Muhar M, Gemberling M, Gersbach CA, Stainier DY, Seydoux G, Mohr SE, Zuber J, Perrimon N (2017) Loss-of-function genetic tools for animal models: cross-species and cross-platform differences. Nat Rev Genet 18:24–40

Israni B, Rajam MV (2017) Silencing of ecdysone receptor, insect intestinal mucin and sericotropin genes by bacterially produced double stranded RNA affects larval growth and development in Plutella xylostella and Helicoverpa armigera. Insect Mol Biol 26:164–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/imb.12277

Janmaat AF, Myers J (2003) Rapid evolution and the cost of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis in greenhouse populations of cabbage loopers, Trichoplusia ni. Proc R Soc Lond B 270:2263–2270

Jia Q, Chen X, Wu L, Ruan Z, Li K, Li S (2018) Matrix metalloproteinases promote fat body cell dissociation and ovary development in Bombyx mori. J Insect Physiol 111:8–15

Joga MR, Zotti MJ, Smagghe G, November Christiaens O (2016) RNAi efficiency, systemic properties, and novel delivery methods for pest insect control: what we know so far. Front Physiol 7:553. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2016.00553

Kim E, Park Y, Kim Y (2015) A transformed bacterium expressing double-stranded RNA specific to integrin β1 enhances Bt toxin efficacy against a polyphagous insect pest, Spodoptera exigua. PLoS ONE 10(7):e0132631. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132631

Knip M, Constantin ME, Thordal-Christensen H (2014) Trans-kingdom cross-talk: small RNAs on the move. PLoS Genet 10:e1004602

Lacey LA, Grzywacz D, Shapiro-Ilan DI, Frutos R, Brownbridge M, Goettel MS (2015) Insect pathogens as biological control agents: back to the future. J Invertebr Pathol 132:1–41

Landy A (1989) Dynamic, structural, and regulatory aspects of lambda site-specific recombination. Ann Rev Biochem 58:913–949

Lavine MD, Strand MR (2002) Insect hemocytes and their role in immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 32:1295–1309

Li YL, Hou MZ, Shen GM, Lu XP, Wang Z, Jia FX, Wang JJ, Dou W (2017) Functional analysis of five trypsin-like protease genes in the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae). Pest Biochem Physiol 136:52–57

Li KL, Yuan SY, Nanda S, Wang WX, Lai FX, Fu Q, Wan PJ (2018) The roles of E93 and Kr-h1 in metamorphosis of Nilaparvata lugens. Front Physiol 9:1677. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01677

Lim ZX, Robinson KE, Jain RG, Chandra GS, Asokan R, Asgari S, Mitter N (2016) Diet-delivered RNAi in Helicoverpa armigera—progresses and challenges. J Insect Physiol 85:86–93

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408

Mohan S, Ma PWK, Williams WP, Luthe DS (2008) A naturally occurring plant cysteine protease possesses remarkable toxicity against insect pests and synergizes Bacillus thuringiensis toxin. PLoS ONE 3(3):e1786. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001786

Navon (2000) Bacillus thuringiensis insecticides in crop protection—reality and prospects. Crop Prot 19:669–676

Newmark PA, Reddien PW, Cebrià F, Sánchez Alvarado A (2003) Ingestion of bacterially expressed double-stranded RNA inhibits gene expression in planarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100(suppl.1):11861–11865

Pan PL, Ye YX, Lou YH, Lu JB, Cheng C, Shen Y, Moussian B, Zhang CX (2018) A comprehensive omics analysis and functional survey of cuticular proteins in the brown planthopper. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:5175–5180

Peralta C, Palma L (2017) Is the insect world overcoming the efficacy of Bacillus thuringiensis? Toxins 9:39. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins9010039

Pfaffl MW (2001) A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29:2002–2007

Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L (2002) Relative expression software tool (REST(C)) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 30:e36

Reboul J, Vaglio P, Tzellas N, Thierry-Mieg N, Moore T, Jackson C, Shin-i T, Kohara Y, Thierry-Mieg D, Thierry-Mieg J, Lee H, Hitti J, Doucette-Stamm L, Hartley JL, Temple GF, Brasch MA, Vandenhaute J, Lamesch PE, Hill DE, Vidal M (2001) Open-reading frame sequence tags (OSTs) support the existence of at least 17,300 genes in C. elegans. Nat Genet 27:1–5

Rutledge RG, Côté C (2003) Mathematics of quantitative kinetic PCR and the application of standard curves. Nucleic Acids Res 31(16):e93. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gng093

Sugahara R, Saeki S, Jouraku A, Shiotsuki T, Tanaka S (2015) Knockdown of the corazonin gene reveals its critical role in the control of gregarious characteristics in the desert locust. J Insect Physiol 79:80–87

Tian H, Peng H, Yao Q, Chen H, Xie Q et al (2009) Developmental control of a lepidopteran pest Spodoptera exigua by ingestion of bacteria expressing dsRNA of a non-midgut gene. PLoS ONE 4(7):e6225. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0006225

Timmons L, Fire A (1998) Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature 395:854

Timmons L, Court DL, Fire A (2001) Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene 263:103–112

Vatanparast M, Kim Y (2017) Optimization of recombinant bacteria expressing dsRNA to enhance insecticidal activity against a lepidopteran insect, Spodoptera exigua. PLoS ONE 12(8):e0183054. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183054

Walhout AJM, Temple GF, Brasch MA, Hartley JL, Lorson MA, van den Heuvel S, Vidal M (2000) GATEWAY recombinational cloning: application to the cloning of large numbers of open reading frames or ORFeomes. Methods Enzymol 328:575–592

Wang M, Weiberg A, Jin H (2015) Pathogen small RNAs: a new class of effectors for pathogen attacks. Mol Plant Pathol 16:219–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/mpp.12233

Wang M, Thomas N, Jin H (2017) Cross-kingdom RNA trafficking and environmental RNAi for powerful innovative pre- and post-harvest plant protection. Curr Opin Plant Biol 38:133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2017.05.003

Wang JD, Wang YR, Wang YZ, Wang WZ, Wang R, Gao SJ (2018) RNA interference of tubulin genes has lethal effects in Mythimna separate. Gene 670:1–6

Weiberg A, Bellinger M, Jin H (2015) Conversations between kingdoms: small RNAs. Curr Opin Biotechnol 32:207–215

Xu Y, Nagai M, Bagdasarian M, Smith TW, Walker ED (2001) Expression of the p20 gene from Bacillus thuringiensis H-14 increases Cry11A toxin production and enhances mosquito-larvicidal activity in recombinant gram-negative bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:3010–3015

Yang J, Han ZJ (2014) Efficiency of different methods for dsRNA delivery in cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera). J Integr Agric 13:115–123

Yu N, Christiaens O, Liu J, Niu J, Cappelle K, Caccia S, Huvenne H, Smagghe G (2013) Delivery of dsRNA for RNAi in insects: an overview and future directions. Insect Sci 20:4–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01534

Zhang J, Khan SA, Heckel DG, Bock R (2017) Next-generation insect-resistant plants: RNAi-mediated crop protection. Trends Biotechnol 35:871–882

Zhu J, Dong YC, Li P, Niu CY (2016) The effect of silencing 20E biosynthesis relative genes by feeding bacterially expressed dsRNA on the larval development of Chilo suppressalis. Sci Rep 6:28697. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep28697

Zotti M, dos Santos EA, Cagliari D, Christiaens O, Taning CNT, Smagghe G (2018) RNA interference technology in crop protection against arthropod pests, pathogens and nematodes. Pest Manag Sci 74:1239–1250

Acknowledgements

L4440 HT115 E. coli were kindly donated by Elia Di Schiavi (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Naples, Italy). This work was supported by the Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca, Futuro in Ricerca 2013 (RBFR13PMT1) (to SC) and by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, under Grant Agreement No. 773554 (EcoStack) (to FP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Communicated by E. Roditakis.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Caccia, S., Astarita, F., Barra, E. et al. Enhancement of Bacillus thuringiensis toxicity by feeding Spodoptera littoralis larvae with bacteria expressing immune suppressive dsRNA. J Pest Sci 93, 303–314 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-019-01140-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-019-01140-6