Abstract

This paper compares the waves of globalization before the outbreak of the Great Recession in 2007 with its alleged historical antecedent before the outbreak of World War One. We describe trends in trade and openness, investigate the proximate causes of changes in openness and estimate the gains from trade from the early nineteenth century onwards. Our results suggest that the conventional wisdom has to be revised. The first wave of globalization started around 1820 and culminated around 1870. In the next century, trade continued to grow, with the exception of the Great Depression, but openness and gains fluctuated widely. They resumed a clear upward trend from the early 1970s. By 2007, the world was more open than a century earlier and its inhabitants gained from trade substantially more than their ancestors did.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction: why revisit globalization?

In 2007, world trade was about two times greater than in 1997, six times greater than in 1972 and 32 times greater than in 1950. This was one of the most evident features of the current wave of globalization, which is widely credited to have fostered economic growth. But, as many scholars have pointed out, the world had experienced a similar process, promptly christened the first globalization, in the decades before World War One (Rodrik 1998; O’Rourke and Williamson 1999; Bordo et al. 2003; Collier and Dollar 2002; Findlay and O’Rourke 2007). In those years, trade rose fast, core countries experienced modern economic growth for the first time in history and growth gradually spread to the periphery via trade. The Great Trade Collapse (Baldwin 2009) and the subsequent stagnation, has suggested less uplifting historical comparisons. The first globalization was arrested by the outbreak of World War One, and, after a modest recovery in the 1920s, was definitively killed by the protectionist reactions to the Great Depression (Eichengreen 2015).

These historical comparisons are part and parcel of the scholarly discourse on the current globalization. They implicitly focus on openness as the mean measure of globalization, as it captures the additional increase of trade beyond the effect of economic growth, and they explain its movements with changes in international trade costs relative to domestic ones (Sect. 2). This literature is arguably flawed (Sect. 3). First, it uses an imprecise measure of openness and does not exploit the recent advances in trade theory. Second, with the notable exception of Hugot (2014), authors ignore the period before 1870, which featured massive convergence of prices within Europe (Jacks 2005; Federico 2011) and worldwide (Sharp and Weisdorf 2013; Chilosi and Federico 2015), as well as an extensive liberalization of trade (Federico 2012; Tena-Junguito et al. 2012). Third, the conventional wisdom relies on very fragile quantitative evidence. Most estimates of openness refer to a few advanced countries in Europe and the Western offshoots. The available series of world trade, dating back to the 1960s and 1970s, neglect all estimates of trade by country published since then and cover peripheral countries very crudely, if at all. The recent wave in gravity models (Anderson and van Wincoop 2004; Head and Mayer 2014; Meissner 2014) suffers from the same advanced country bias and, on top of this, relies on data on bilateral flows, which are notoriously the least reliable information in historical trade statistics (Federico and Tena-Junguito 1991).

This paper aims at putting these historical comparisons on a solid quantitative ground. To this aim, we have estimated yearly series of trade for all polities since 1850, at the latest, to 1938 (Federico and Tena-Junguito 2016a) and we have collected all the available data on historical national accounts for the same period (Appendix C of Electronic Supplementary Material). Extending these series to present with the data from the United Nations, in this paper we make four contributions:

-

i.

We sketch out the growth of world trade since 1800, focusing on the comparison between the two globalizations (Sect. 4).

-

ii.

We describe trends in openness, defined as the ratio of exports to GDP at current prices, from 1830 onwards (Sect. 5).

-

iii.

We analyze the proximate causes of movements in world openness, distinguishing changes in the distribution of world GDP, changes in the composition of GDP by sector and a residual, which captures changes in trade costs (Sect. 6).

-

iv.

We compute the gains from trade using both the statistics by Arkolakis et al. (2012) and the extended version by Felbermayr et al. (2015), and we discuss their possible biases (Sect. 7).

Section 8 tests the robustness of our results to different sets of GDP data, different measures of openness and alternative weighting systems of country series, and Sect. 9 concludes.

2 Openness in historical perspective: a survey

The literature on trade in the last two centuries is huge (Findlay and O’Rourke 2007), but there are comparatively few estimates of openness in the long-run. Feenstra (1998) and Baldwin and Martin (1999) report ratios of total merchandise trade (imports plus exports) to GDP for selected countries at benchmark years, while Maddison has published two overlapping estimates for the “world” export/GDP ratio at constant prices. The ratio soared from 1% in 1820 to 5% in 1870 (Maddison 1995, p. 38), continued to rise, although more slowly, to 7.9% in 1913 and to 9% in 1929 (Maddison 2001, Table F5). The twin shock of the Great Depression and World War One reduced the ratio to 5.5% in 1950, but the 1998 ratio (17.2%) was more than double its 1913 level. In a recent paper, Klasing and Millionis (2014) have published series of openness for a large number of countries (up to 62 in some years) from 1870 to 1949, which they obtain by dividing total trade from Barbieri et al. (2009), Barbieri and Keshk (2012) by their own ‘synthetic’ series of GDP at current prices (See Appendix C of Electronic Supplementary Material). They sum up these country series to get a series of world openness, which they extend to 2005 with data from the Penn Tables. It increases by a third until World War One, from less than 20–30% and then, after the collapse of the 1930s, to about 40% in the late 1990s and 50% in 2005. Thus, they conclude that the world was more open in the late 1990s than in 1913, but their estimate of the gap is substantially smaller than Maddison’s.

As an alternative to direct measuring, one can infer the potential for globalization from a measure of trade costs. First, one can compare the (time-invariant) coefficients of distance in gravity equations for different periods of time—interpreting lower coefficients as evidence of lower transaction costs. Second, one can estimate bilateral trade costs as

where ε is the elasticity of trade to trade costs, X are trade flows, and subscripts refer to international (Xij and Xji) or domestic (Xii and Xjj) trade flows (Head and Ries 2001; Jacks et al. 2006). The resulting series can be weighted with country shares on GDP or on trade to get indexes of world (or regional) trade costs.

Neither method confirms the conventional wisdom regarding the second globalization. The careful survey by Disdier and Head (2008) shows that the coefficients of gravity equations are not lower in the 1990s and early 2000s than in the 1950s–1960s, and scholars have put forward several hypotheses to explain this outcome (Carrere and Schiff 2005/2006; Hummels 2007; Berthelon and Freund 2008). The results of estimates of trade costs since 1870 by Jacks et al. (2011) and since 1830 by Hugot (2014) with Eq. 1) are quite sensitive to the country coverage, methods of computing domestic trade flows and of aggregating across countries. For instance, Hugot (2014) finds a sharp decline in costs after 1950 for his full sample, which almost disappears for time-invariant samples (compare his Figs. 5 and 6). Costs in 2007 are much lower than 1913 for peripheral European countries and the rest of the world, but similar for the USA and France and much greater for the United Kingdom (Fig. 7). These estimates proxy domestic flows with the difference between GDP and exports, but both Jacks et al. (2011, Fig. A4.b) and Hugot (2014, Fig. 31) find a sizeable decline in costs after 1970 if domestic flows are computed as the difference between gross output of tradables (agriculture and manufacturing) and exports. In a more general vein, as Hillberry and Hummels (2014, point out, Eq. 1) assumes that the allocation of trade between domestic and foreign flows, and thus ultimately the allocation of consumption of tradables between domestic and foreign producers, depends entirely on trade costs. This rules out any effect of technological or demand-side shocks.

3 Measuring openness and gains from trade

The openness of the ith country (Grassman 1980) is usually computed as the ratio of merchandise (M) exports and imports to GDP

This definition is not suitable for measuring world openness because, by convention, trade statistics include transportation and related costs in imports. Therefore, world openness would appear to decrease (increase) if these costs decrease (increase) even without any change in actual trade flows. Thus, following Maddison (1995), we prefer to define world openness as the ratio of exports to GDP

which is roughly a half the standard measure for a country.Footnote 1 We also compute the ratio of exports to production of tradables only (or ‘openness tradables’) as

The ratio aims to capture the impact of globalization on sectors that actually competed on the world market (Feenstra 1998).

As discussed in more detail in Appendix A of Electronic Supplementary Material, both measures of openness are biased. The numerator underestimates trade because it omits services, and the numerator and denominator are inconsistent because the former includes and the latter excludes intermediate products. Other, more accurate, measures of openness can be computed with the available data only after 1970 (Sect. 8) and even them, although closer to, fall short of the ‘ideal’ index.

We decompose changes in world openness (OW) as

where αi is the share of the ith country in world GDP, βij is the share of the jth sector in the GDP of the ith country, and ωij is the ratio of exports to the VA of the jth sector in the ith country. The first term of Eq. 5) measures the effects of changes in the country distribution of world GDP (henceforth location effect), the second the effects of changes in the composition of the GDP by polity (or structural change), while the third (or residual) the changes in the export/GDP ratio by sector/country. If the data by sector were detailed enough, the residual would capture the effect of changes in trade costs on openness. Unfortunately, the historical data on the composition of GDP are not very detailed for most countries, and thus we have been forced to distinguish between tradable and non-tradables, as proxied by services (Appendix C.4 of Electronic Supplementary Material). Thus, the residual includes the effects of changes in the composition of tradables, which would reinforce (offset) the pure effect of trade costs if the growing sectors are more (less) open than the rest of tradables.

In their seminal article, Arkolakis et al. (2012) define the (static) gains from trade as the increase in income that would compensate the representative consumer from a move to autarky. They show that gains for the ith country can be measured as

where λii is the share of domestic expenditures and ε is the (absolute value of the) elasticity of trade to trade costs. Then country gains can be aggregated in a world-wide index by weighting with shares on GDP (βi)

or on population (χi)

This estimate henceforth ‘baseline’) assumes a simple Armington framework, with one good in multiple varieties (a domestic one plus as many imported ones as trading partners), and thus one single trade elasticity ε, no trade in intermediate goods, balanced trade and iceberg trade costs. These assumptions have been relaxed in subsequent work. Costinot and Rodriguez-Clare (2014) put forward more complex (and thus realistic) models, featuring (different combinations of) multiple sectors, with or without free entry, trade in intermediate goods, multiple factors of production and monopolistic competition without firm heterogeneity (à la Krugman) or with firm heterogeneity (à la Melitz). All these models imply that the baseline Arkolakis et al. (2012) statistics underestimate gains from trade. Costinot and Rodriguez-Clare (2014) estimate that gains for a sample of 40 countries in 2008 were three times higher than the baseline for models with multiple sectors and up to nine times higher for models with multiple sectors and trade in intermediated goods.Footnote 2 Ossa (2015) shows that using sector-specific trade-elasticities rather than a single economy-wide parameter increases gains in a multiple-sector model from 16.9 to 55.6% (for all countries in 2007). Simonovska and Waugh (2014b) explore the same issue from a different perspective. They estimate, with a price-based method devised by Eaton and Kortum (2002), the elasticity ε which would yield the observed pattern of trade in 2004 with a baseline Armington model (comparable to the Arkolakis et al. statistics) and with four alternative, more complex, models. All these latter imply that the true trade elasticity were lower than the baseline one, and gains correspondingly higher, up to 40%.Footnote 3

On a different line, Felbermayr et al. (2015) argue that tariffs must be treated differently from other trade costs, as revenues is redistributed back rather than disappear. They suggest adjusting the baseline formula to

where μ, or the tariff multiplier, is defined as μ = 1/(1 − T/E), T is the tariff revenue and E the domestic expenditure, net of tariffs, while δ and η measure respectively the degree of oligopoly in the product market and firm heterogeneity à la Melitz. By construction, gains are bound to be higher than in the baseline and, ceteris paribus, the difference is proportional to tariffs.Footnote 4

4 The growth of world trade

Our trade database is organized by polity (independent country, colony or pre-colonial corresponding native territory): for each polity, we estimate series of imports and exports, at current and constant (1913) prices and at current and constant (1913) borders.Footnote 5 The data-base includes 11 polities from 1800, accounting for 55% of world exports in 1850, 62 from 1823 (80% of world exports in 1850) and 89 from 1830 (95%). After 1850, we have estimated trade for around 130 polities—i.e. all existing ones, with very few and quantitatively negligible exceptions.

We obtain our series of world trade from 1850 to 1938 by summing up exports at current prices, and we extend it to 1800 adjusting for changes in coverage the sample before 1850 (Federico and Tena-Junguito 2016a) and to 2007 by linking it to the current United Nations series (UN Statistical yearbook) in 1938. The resulting series (Fig. 1) grew at an impressive annual rate of 4.22% (significant at 1%), corresponding to a cumulated increase by 6437 times.Footnote 6

Sources: 1830–1938: Federico and Tena-Junguito (2016a) and 1950–2010 Appendix D (online)

World Export at constant prices, (1913$) Log scale 1800–2010.

The two World Wars and the outbreak of the Great Depression were clearly major structural breaks, while Bai and Perron (2003) tests single out suggest additional structural breaks in 1817 and 1865 in the period 1800–1913 and, less clearly, in 1970 or 1980 for 1950–2007. Table 1 reports the rates of change for the resulting eight periods, as well as for three longer ones.

World exports started to grow fast after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The early rise reflects also the return to normal trading conditions after the shock of the Wars, but this effect accounted for less than 7% of the increase of trade until 1865 and for less than 2% of overall growth before World War One.Footnote 7 Contrary to conventional wisdom, trade grew faster in 1817–1866 than in 1867–1913 and the difference is significant at 1%. If trade had continued to grow as fast as before 1867, in 1913 it would have been 55% higher. The outbreak of World War One caused world exports to fall by about a quarter, as much as estimated by Glick and Taylor (2010) with a different method. World trade returned to its pre-war level in 1924 and continued to grow until 1929. The Great Depression caused trade to collapse: in 1913 it was below its pre-war level and the following recovery was only partial. In contrast, world trade recovered quite quickly after World War Two. By 1950 it was already 10% higher than in 1929 and grew at breakneck speed during the golden age, returning close to its pre-1913 growth path (Fig. 1). Growth in trade slowed markedly in the 1970s but accelerated again from 1980 onwards. From 1995 to 2007, the level of trade exceeded the pre-war growth path, but it converged back to it during the Great Recession.

Part of the long-run increase in trade reflects the growing political fragmentation. We estimate that, without the creation of new states after World War One in Europe and the Middle East, in 1924 world exports would have been 2.9% lower (and European exports 6.3% lower).Footnote 8 The gap has been shrinking during the interwar years—so that the series at current borders underestimated the growth of trade relative to the estimate at constant 1913 borders.Footnote 9 Lavallée and Vicard (2013, Table 4) estimate that further border changes (the partition of British India in 1946 and of British and French African colonies in the 1950s and 1960s and the fragmentation of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia in the 1990s) accounted for 6.6% of the growth of trade during the Golden Age and for about a sixth of the overall rise from 1950 to 2007. This is equivalent to a third of a percentage point of the growth rate—i.e. to about a fifth of the difference between the two globalizations.

In the long run, exports of all polities increased, but not to the same extent. For instance, the United Kingdom was by far the largest exporter in 1850 (19% of total at current prices) and still in 1913 (13.7 vs. 12.9% for Germany and 12.8% for the United States), but only the 10th largest in 2007 (3.2%). China was the 11th largest in 1850 (2.3% of world exports), slid to 17th place in 1913 (1.6%), and rose to second place in 2007 (8.9%, behind Germany with 9.6%). Most of these changes took place during the second globalization: the simple coefficient of correlation between shares by polity are higher between 1850 and 1913 and between 1913 and 1972 (0.91 and 0.87) than between 1972 and 2007 (0.84). A simple division of countries by continent and by level of development highlights the main patterns (Fig. 2).Footnote 10

Sources: 1830–1938: Federico and Tena-Junguito (2016a) and 1950–2010 Apendix D (online)

Distribution of world exports at current prices 1830–2010. a Shares by continent (%). b Shares by level of development (%).

In the early 1830s, Europe accounted for 62% of world exports and the advanced countries for about a half. This latter share increased by ten points in the 1850s and then remained around 60% until 1913, while the share of Europe drifted slightly downwards to 56%. The two World Wars and the Great Depression caused substantial changes in shares, which were however largely reversed during the Golden Age. In 1972 Europe still accounted for 52% of world exports and the ‘old rich’ for 57%. In contrast, the changes after 1972 have been large and (so far) permanent. The share of Asia rose from about a sixth to a third, at the expense of all other continents. Europe’s share slid from over a half to about 45%, and thus it fared better than the Americas (a fall from a quarter to slightly above one-sixth), Africa and Oceania. Until the early 1990, the fall in the share of ‘advanced countries’, from 56% to about 40% of world exports, was compensated by the relative increase of exports from the ‘other OECD’ countries—most notably Japan. In the last fifteen years, exports from the ‘advanced countries’ decreased further to slightly over a third, the ‘other OECD’ countries returned to a sixth, their level of the 1970s, and the ‘rest of Asia’—i.e. mostly China- jumped to a quarter of the world market.

5 Globalizations and openness in the long run

We have collected historical series of GDP at current prices for 38 polities, starting as early as 1800 for the United States and Sweden (cf. Statistical Appendix Table S.1 for the list and Appendix C of Electronic Supplementary Material for the sources), and we have been able to extract GDP data from UN sources, with some adjustments, for all but one (Austria-Hungary) in 2007. There is no doubt that by then these 37 polities were more open than in 1913, both as an aggregate (their export/GDP ratio being 22.5 vs. 12.5%) and individually (there were only nine exceptions, the most notable ones being India and the United Kingdom). They accounted for 90.4% of world trade in 1913 and for 81.3% in 2007, but the world would have been more open in 2007 than in 1913 even if the remaining polities had exported nothing. This hypothesis is clearly absurd: in reality, in 2007 the export/GDP ratio for the rest of the world was 30.9%.

We prefer not to compute aggregate export/GDP ratio with all available polity series, as changes in coverage could introduce spurious movements in the resulting series. Instead, we have selected two different time-invariant samples, featuring 18 polities from 1830 (‘1830 sample’) and 29 from 1870 (‘1870 sample’). In spite of the small number of polities, these samples are quite representative: the ‘1830 sample’ accounted for 58.3% of world trade in 1850 and the ‘1870 sample’ for 79.6% in 1913, for 73.5% in 1973 and for 53.8% in 2007. Furthermore, it can be shown that the ‘1870 sample’ captures quite well the world-wide trends after 1973: the coefficient of correlation with the export/GDP ratio for all countries in 1973–2007 is 0.982 and the rates of change are almost identical (Statistical Appendix S.2 of Electronic Supplementary Material).

A visual inspection of the series (Fig. 3), supported by a statistical analysis of rates of change (see Statistical Appendix S2 of Electronic Supplementary Material), highlight two major waves of globalization separated by a century of fluctuations.Footnote 11

Sources: Exports of goods: Federico and Tena-Junguito (2016a) and Appendix D (online); GDP: Appendix C (online)

World openness at current prices, 1830–2007.

-

i.

From 1830 to 1870 the export/GDP ratio for the ‘1830 sample’ doubled, from 6 to 12%—i.e. it grew significantly faster than openness for the same countries during the second globalization and as fast as openness for all countries. If anything, the results underestimate the growth in openness. In fact, the trade per capita of the omitted polities tripled from 1830 to 1870 but very few among them experienced significant growth in GDP per capita.Footnote 12 The same reasoning implies that openness had been growing before 1830. This hypothesis is confirmed by the few series available, with the conspicuous exception of the United States.Footnote 13

-

ii.

The export/GDP ratio for the ‘1870 sample’ fluctuated with no trend for most of the period from 1870 to World War One, rose in the early 1910s to a peak of almost 14%, fell during the war, remained low in the 1920s, collapsed to a minimum of 6.7% in 1936 and recovered only partially during the Golden Age. Openness in the early 1970s was similar to the level of the late 1920s and about two points lower than a century before. It is possible that the ratio in the rest of the world was marginally higher in 1973 than in 1870, as before 1913 their exports increased a little more and GDP grew much less than those of the 29 countries. Thus, for instance, the export/GDP ratio for China soared from less than 0.5% in the 1830s to around 1.2% in the early 1870s and doubled again on the eve of World War One. However, this would not change the main conclusion. The fast rise of trade before World War One matched or barely exceeded the growth of GDP, and its post-1950 boom healed the wounds of the Great Depression and of the two World Wars.

-

iii.

Openness rose very fast from the early 1970s to 2007, doubling (from 9.9 to 19.2%) for the ‘1870 sample’ and increasing by 2.5 times (from 9.6 to 23.7%) for all countries. As discussed in more detail in Sect. 8, the ratios soared during the oil crises, up to 17% in 1980, stagnated for about fifteen years and resumed their growth after 1995.

The worldwide aggregates conceal wide differences among polities. As expected, the level of openness is negatively related to the size of the country. A simple log–log regression of export/GDP ratio with population yields coefficients of −0.16 in 1913 and −0.21 in 2007, both significant at 5%. Interestingly, dummies for continents and landlocked countries are not significant. However, the dispersion of country ratios did not change in the long run and most polities shared the worldwide growth in openness during the two waves of globalization. In 1830–1870, the export/GDP ratio increased in 15 polities out of 18 of the 1830 sample, stagnated in the United States and declined only in two tropical exporters, Brazil and Jamaica. Since 1972, openness has grown in 90 countries out of 124, with a median increase of one half. Openness has decreased only in very small countries (the biggest being Cuba) and this decline has been more than compensated by the leap forward of the former Soviet Union (from 3 to 30%) and of China (from 2.5 to 35%). In contrast, from 1870 to 1970, polity specific movements diverged from aggregate trends in more than a third of cases. Somewhat surprisingly, ten polities, including Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom were more open in 1950 than in 1913.

The impact of the second globalization is even more evident if we focus on the openness tradables (Fig. 4). We can compute this measure for eight countries, six Europeans, including Great Britain and France, plus Australia and Peru, from 1830 (‘1830 tradable sample’) and for sixteen, including all the advanced countries, Japan and India, after 1870 (‘1870 tradable sample’).

Sources: Export goods: Federico and Tena-Junguito (2016a) and Appendix D (online); GDP tradables: Appendix C (online)

World Openness tradables at current prices 1830–2007.

By construction, openness tradables must be higher than openness, but the striking fact is the widening of the gap during the second globalization. In the nineteenth century, the ratio was slightly above 1.5 for both the ‘1830 tradable sample’, and the ‘1870 tradable sample’. It rose to 1.90 in 1913, continued to climb to 2.40, declined somewhat during the Great Depression, recovered up to 2.5 in the early 1970s and jumped to 3.5 times in 2007. The ratio between the two measures for all countries increased even faster, from 1.5 in 1970 to 2.6 in 2007. Thus, arguably, the growth in the aggregate export/GDP ratio since 1973, however impressive, undervalues the differences between the two globalizations.

6 The proximate causes of changes in openness

The decomposition of the increase in openness from 1830 to 1870 according to Eq. 5) shows zero location effect and a modest negative impact of changes in location, which reduced openness by 0.3 points. Thus, the first globalization is explained exclusively by the residual—i.e. by the fall in trade costs. This conclusion is plausible, but unfortunately, the ‘1830 tradable sample’ is hardly representative. It accounted for only 40% of world exports in 1850 and, above all it does not include the United States, which in those years jumped from a sixth to a third of the GDP of the ‘1830 sample’. We explore the effect of this massive change in location of GDP by decomposing the growth in openness for the ‘1830 sample’ into the location effect and the residual. As expected, the relative rise of the United States reduced openness by 0.4 points but it was compensated by other changes in the distribution of GDP. Thus, the total location effect was positive, accounting for about a tenth of the total rise in openness for the ‘1830 sample’. All the rest is explained by the residual, which includes the structural change—in all likelihood quite modest.

Representativeness is much less an issue for the ‘1870 tradables sample’, as its sixteen countries accounted for 67.6% of world exports in 1913 and for 47.2% in 2007. We report the result of the decomposition in Table 2, adjusting the signs of percentage changes so that a positive (negative) sign corresponds to an increase (decrease) in openness.

In the whole period, changes in the distribution by country (location effect) and in the composition of GDP (structural change) reduced potential growth by 1.3 and 5.3 points, respectively. Structural change reduced openness in all periods but 1932–1950 but the effect is especially large from 1973 onwards, when tradables decreased from 40 to 27% of the total GDP of these sixteen polities. In contrast, most of the negative location effect is found before 1950. The column ‘location USA’ shows that it is mostly accounted for by the rise of the United States from 28% of the GDP of the sample in 1870 to 39% in 1913 and then to 65% after the war Since 1950, the share of the United States has been declining, and the location effect has turned positive.

In spite of the negative contributions from structural change and location, the export/GDP ratios increased by about seven points thanks to the residual. In theory, this latter might reflect the positive effect on trade of the convergence in income levels among polities of the sample, but this does not seem the case.Footnote 14 In contrast changes in the residual tally well with the evidence on movements in trade costs. The fast increase in openness in 1830–1870 and 1972–2007 coincides with a period of intensive trade liberalization, and its collapse in 1929–1932 with the protectionist backlash during the Great Depression. The modest rise in 1950–1972 could be explained by the first stage of the post-war liberalization, while the increase 1870–1913 is likely to reflect a decline in transportation costs, as barriers to trade did not differ much between those years.Footnote 15

7 Gains from trade

The key parameter for the estimate of gains by Arkolakis et al. (2012) is the trade elasticity ε. Head and Mayer (2014, Table 5) survey 32 econometric estimates, which yield an average of 5.13 and a median of 3.78. A range around 4 is confirmed by the recent estimates, with different methods, by Simonovska and Waugh (2014a), Ossa (2015) and Caliendo and Parro (2015). We thus assume ε = 3.78 and, following the standard practice, we proxy λ (the share of expenditure in domestic goods) with the difference between GDP and imports at current prices.

Consistently with the levels of openness, gains (Table 3) were greater in 2007 than in 1913 both on average and for most polities.

The difference is huge for China or Russia, which opened world trade during the second globalization. In contrast, gains were lower in 2007 than in 1913 in exporters of primary products turned inwards, such as Argentina, Brazil and Cuba in Latin America and some Western offshoots.

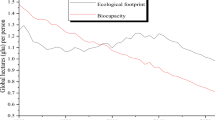

We obtain a yearly series of world gains for the ‘1830 sample’ and the ‘1870 sample’ by weighting the polity series with their shares on total GDP at current prices (Fig. 5). The coefficients of correlation between the three series are very high—0.979 between the ‘1830’ and ‘1870 sample’, and 0.935 and 0.982 respectively with the ‘all country’ series gains, available from 1972. Not surprisingly given the formulas, gains and openness are strictly correlated—a coefficient of 0.91 for the 1870 sample.Footnote 16 It would thus be redundant to describe in any detail the trends. We will just add that a back-of-the-envelope estimate for all countries suggests a five-point increase in gains, from 2.8% in 1972 to 7.8% in 2007, slightly higher than the comparable estimate for the ‘1870 sample’.Footnote 17

Sources: See text Sect. 3

Gains from trade 1830–2007 as percentage of GDP.

Before 1870, globalization benefitted mostly the rich countries (as defined in Sect. 4). In 1830, the GDP-weighted gains were around 2.3 points for both rich and poor countries, but by 1870 gains had risen to about 4.5% of GDP for the former and to about 3% for the latter. From 1870 to 1913, the gains for the rich countries fluctuated around 4.5–5%, while those of the rest of the world, inclusive of India and Japan, almost doubled. Yet, in 1913 the GDP-weighted average was still a point higher for the rich countries than for the rest of the world (5.2 vs. 4.3%). The Great Depression hit both groups badly, reducing the gains to the level of the 1830s. Trends diverged somewhat afterwards. The gains for the advanced countries remained rather low in the 1950s and increased very slowly during the Golden Age, so that by 1973 they were still lower than in 1913 by a third. In contrast, gains for the rest of the world recovered in the late 1930s and during the war, but declined in the 1950s and 1960s. While the second globalization benefitted both groups, the rich were marginally better off. Their gains increased by 2.5 times, to 8.1% of GDP, while those of the rest of the world only doubled, to 6.2%.

Our estimates might seem low relative to the hype surrounding globalization. To what extent can the treatment of tariffs as ‘normal’ trade costs, the assumption of constant trade elasticity and the use of the simplest model explain them?

-

i.

Estimates with the Felbermayr et al. (2015) formula (Table 3, columns ‘Felbermayr baseline’) always exceed the baseline gains, but the gap is substantially larger in 1913 (about two-thirds) than in 2007 (about a seventh).Footnote 18 The decline is confirmed by the yearly series of tariff-adjusted gains which can be estimated for a small number of advanced countries: the ratio to the baseline estimate remains around 1.30–1.40 for most of the period, with a spike over 1.70 in the 1930s, but it declines from the 1970s to about 1.10. This trend reflects the liberalization of trade and possibly the increasing use of quantitative restrictions rather than duties as a tool for protection.

-

ii.

Our estimate would bias gains upwards (downwards) if the true elasticity were higher (lower) than 3.78. For instance, with ε = 5, as assumed by Constinot and Rodriguez-Clare (2014) and Felbermayr et al. (2015), or ε = 8, as hypothesized by Jacks et al. (2011) in their baseline estimation, average gains over the whole period 1870–2007 for the ‘1870 sample’ would be reduced from 4.11 to 3.08 and 1.91%, respectively. For instance, had it increased linearly from 3.78 in 1870 to 7 in 2007, gains would have remained stable around 3.5% of GDP (but only 1.6% in the 1930s). Such a massive change in trade elasticity is implausible. Indeed Hugot (2014) estimates, with two different versions of a gravity model, that the elasticity of French trade from 1829 to 1913 fluctuated in the short run without any clear trend. Furthermore, his median estimates (4.84 and 4.93) are not statistically different from 3.78. Waiting for further actual work, one might start by discussing the origin of possible changes. Even assuming no change in product specific trade elasticities, the aggregate ε would have changed if elasticities differed by product, given the well-known changes in the composition of world trade. Caliendo and Parro (2015) estimate that in 1993 elasticities were higher for agricultural goods (8.11) and mineral products (15.7) than for manufactures. In this case, the growth of intra-industry trade in manufactures after World War Two would have decreased elasticity and thus, ceteris paribus, increased gains from trade. In contrast, Ossa (2015) finds no systematic differences in elasticities for primary products and manufactures in 2007 (the unweighted averages being 3.54 and 3.62).

-

iii.

The shortage of data make it very difficult to estimate any of the models put forward by Costinot and Rodrigues-Clare (2014). We can only replicate the adjustment for monopolistic competition by Felbermayr et al. (2015). The gains (Table 3, column ‘Felbermayr extended’) are a bit larger than the baseline but the difference is modest. However, this by no means implies that the difference would be modest if it were possible to estimate a model with multiple sectors and monopolistic competition and possibly sector-specific elasticities. It is likely that the gap was larger in 2007 than in 1913, as monopolistic competition and trade in intermediate products are much more relevant now than on the eve of World War One.

8 Robustness checks

In this section, we deal with the robustness of results to alternative GDP data, country weighting schemes and formulas for openness

We compute two alternative series of openness to check the robustness of our baseline estimates. First, we get a series at constant prices by converting our export series in 1990 PPP dollars and dividing the result by total GDP.Footnote 19 The full samples includes up to 51 polities, but we prefer to focus on the polities of the ‘1830’ and ‘1870 samples’ for a direct comparison with trends at current prices (Fig. 6)

Sources: Exports of goods: Federico and Tena-Junguito (2016a) and Appendix D (online); GDP: Appendix C (online)

World openness 1830–2007, Current and constant prices. a 1830 sample (18 polities). b 1870 sample (29 polities).

As a rule, openness grew systematically more, and declined less in the interwar years, at constant prices than at current prices (Appendix Table S.2 of Electronic Supplementary Material). The difference is statistically significant before 1870, in the interwar years and after 1973. This implies that the prices of exports declined relative to the prices of imports and/or prices of tradable goods. Relative prices of imports might increase because of protection, while prices of non tradable would rise if productivity grew less (the Baumol effect, more likely in advanced countries) and/or domestic prices in less developed countries converged towards ‘world’ (i.e. American) levels (see Appendix B of Electronic Supplementary Material). There is a considerable exception to this rule. From 1972 to 1980, openness for the ‘1870 sample’ soared from 10 to 15.2% if measured at current prices, and grew only from 9.6 to 11% if measured at constant prices. The ratio between the two measures of openness increased from 1.05 to 1.38, to return to 1.04 in 1986. This movement is surely related to the twin oil shock, but it is not exclusively determined by prices of oil. In fact, the ‘1870 sample’ only features one oil exporting country, Venezuela, which experienced a 6.5 increase in the ratio of openness at current to constant prices. Yet the increase was even larger in Turkey (by 7.6 times) while it was zero or negligible in Austria, Switzerland and India. As a first approximation, the size of the shock and its duration seem inversely related to GDP per capita—i.e. the advanced countries with diversified exports had smaller and shorter cycles than exporters of primary producers.

Second, we compute export/GDP ratios at current prices using as the denominator the synthetic estimates by Klasing and Millionis (2014). We have computed 45 of these ‘hybrid’ openness series, but as before we prefer to limit the comparison to 27 of them, all the polities of the ‘1870 sample’, but Cuba and Peru (Fig. 7).

These ‘Klasing and Millionis’ series grows faster than our baseline series before 1913, and decline less in interwar years, although only the former difference is statistically significant.Footnote 20 Thus, the Klasing and Millionis (2014) method systematically underestimates the growth in GDP relative to the national accounts, in all likelihood because the method assumes no convergence of prices towards the ‘world’ level (cf. Appendix B of Electronic Supplementary Material).

It can be argued that weighting polities with their total GDP is unfair because it values more the welfare of individuals from wealthy countries. Indeed, re-weighting openness and gains of trade with population (from Federico and Tena-Junguito 2016b and United Nations 2011) highlights some sizeable differences before 1913 and during the Golden Age (Fig. 8).

Sources: a see sources Fig. 6b; population from Federico and Tena-Junguito (2016b) and United Nations (2011). b See sources Fig. 5; population from Federico and Tena-Junguito (2016b) and United Nations (2011)

Alternative estimates, World Openness 1870 sample: population weighting. a Trade openness. b Gains from trade.

The population-weighted series of gains from trade increased before 1913 and declined during the Golden Age, instead of remaining roughly constant in both periods. In spite of the growth after 1973, by 2007 it was still 4.2 points below the GDP weighted series and only 1.5 above its level in 1913. The difference between the two series depends on India, which accounted for about half of the population of the 1870 sample but for less than 5% of its total GDP.

Last but not least, one could rise some more fundamental objections to our measures of openness. One could find the argument for the use of exports than total trade in the numerator, although correct at a worldwide level, not appropriate for small samples. Furthermore, the export/GDP ratio may differ from ‘true’ openness, as discussed in Sect. 3 and Appendix A of Electronic Supplementary Material. We tackle the first objection by re-computing openness according to the standard definition, for the ‘1870 sample’ (Statistical Appendix Table S.2 of Electronic Supplementary Material). The differences are negligible for the worldwide series (the coefficient of correlation of 0.996) but also very small for individual polities (the average coefficient of correlation is 0.939 with a minimum of 0.83 for India).

We can explore the potential biases in the export/GDP ratio after 1973, thanks to data on trade in services for all countries from the United Nations and on gross output of agriculture and manufacturing for 15 OECD countries (see Appendix C of Electronic Supplementary Material). Adding trade in services to the numerator (Eq. A.8 c) increases the rate of growth in openness for all countries by half a point, from 1.49 to 1.90%, while also adding gross output in the denominator (Eq. A8.f) raises the rate of growth in openness for the 15 countries from 1.19 to 1.79%. Both differences are significant—i.e. our baseline definition of openness (Eq. 4) undervalues its growth during the second globalization. The bias also affects the estimates of gains. Computing domestic flows λii as the difference between GDP and imports of goods and services (rather than goods only) for all countries increases gains by 0.3 points of GDP in 1980 and by 1.8 in 2007. Computing these flows as the difference between gross output and total imports (including services) raises the gains from trade for 15 advanced countries by 0.5 points (i.e. by a sixth) in the early 1970s and by 6.3 (i.e. by over two-thirds) at the end of the period.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to replicate these computations for the first globalization. The quantitative evidence on gross output/VA ratios is limited to agriculture (Federico 2004) and to the energy intensity of GDP (Kander et al. 2013). There is abundant anecdotal evidence on the international trade in services before 1913 and it is safe to assume that was much less developed than nowadays. It was limited to banking and shipping services, and the United Kingdom was the main world supplier of both. On average the United Kingdom’s exports of services accounted for a quarter of her merchandise exports in 1870–1913 (Mitchell 1988, p. 871), equaling 3.9% of world trade. In contrast, export of services were equivalent to almost a fifth of trade in goods in 2004–2007. Thus, in all likelihood, our comparison based on trade in goods only underestimates the difference between the two globalizations.

9 Conclusions

We can sum up our results in a single sentence: the conventional periodization of the two waves of globalization has to be revised and the differences between them were substantial. The first globalization pre-dated 1870, while the period 1870–1913 can be more accurately described, at least for the major countries, as the first stage of a century long era of fluctuations in the degree of globalization. Both openness and gains from trade remained broadly constant until World War One, fell dramatically during the Great Depression and recovered in the 1950s and 1960s. At the time of the first oil crisis, the world was not significantly more open than a century before and the overall gains from trade were significantly lower.

The following thirty years featured a massive transformation, which differed from the first globalization in four ways:

-

i.

the distribution of world trade by country changed more and faster than in any other comparable period, thanks to the rise of China and other Asian countries;

-

ii.

in spite of a substantial number of exceptions at a country level, world openness was substantially higher in 2007 than in 1913, and the measured gap is likely to underestimate the true one due to the omission of trade in services;

-

iii.

gains from trade in 2007 were larger than in 1913 by about two-thirds, according to the baseline Arkolakis et al. (2012) statistics or by about a sixth with the adjustment for returned tariff revenue (Felbermayr et al. 2015). Both measures clearly underestimate the gains and, on balance, it seems more likely that the gap with the ‘true’ (and unmeasurable) gains was larger in 2007 than in 1913;

-

iv.

the second globalization benefitted slightly more the advanced countries, while before 1913 gains had been substantially larger for the poor countries

Our analysis of the proximate causes of changes in openness points to a major role of the residual, and thus in all likelihood to movements in trade costs. They accounted for all the growth in openness in 1870–1913 and 1973–2007 and, possibly also in 1830–1870, and for the collapse of the interwar years. There are, however, differences in the impact of changes in composition and world distribution of GDP. The rise of the United States dragged down the growth of openness before 1950, while the growth of services reduced it in the second globalization.

The last point relates to the current debate on the future of world trade. The growth in openness for tradables since 1970 is too fast to be explained only by the fall in transportation costs and/or fall in barriers to trade for an invariant bundle of consumption goods. It must reflect also the growing exchange of varieties of the same consumer goods and, above all, the development of international supply chains (Baldwin and Lopez-Gonzales 2013). It is still debated whether these processes have peaked or not (Boz et al. 2015; Constantinescu et al. 2015; Hoeckman 2015; Timmer et al. 2016), and consequently whether the level of openness of the late 2000s will prove to be a historical peak as was the 1913 one, as suggested by the Economist already two years ago (A troubling trajectory Dec 13th 2014). We will not speculate further on this. Suffice to say that, in spite of the likely similarities in its causes, so far the second globalization has been deeper and farther reaching than the first.

Notes

It would be exactly a half if trade is balanced, lower (higher) if the country ran a deficit (surplus) in its trade balance. The bias from surpluses and deficits would disappear at world level, as they cancel each other out.

The baseline formula and the equivalent model with one sector producing several varieties of the same good yield an average of 4.4% of GDP. Gains are 15.3% of GDP for a model with multiple sectors, no trade in intermediate goods and no free entry, 14% for a model with multiple sectors, no trade in intermediate goods and free entry, 15% for a model with multiple sectors, no trade in intermediate goods and two factors of production, perfectly mobile across sectors, 27% for a model with multiple sectors and trade in intermediate goods, under perfect competition, 32% for the same model with monopolistic competition without firm heterogeneity (à la Krugman) and 40% for the same model with firm heterogeneity (à la Melitz).

They obtain ε = 5.24 for the baseline Armington (and the monopolistic competition à la Krugman), 4.17 for the extended baseline, 2.74 for the extended baseline with mark-up and 3.7 for monopolistic competition à la Melitz (Table 7). The corresponding gains in 2007 for our sample of 37 countries (see Sect. 6 for details) are 4.0, 5.1, 7.9 and 5.8%.

They estimate that gains for 11 countries in 2008 were about a quarter higher than with the Arkolakis et al. (2012) statistics.

Whenever available, we use modern estimates of trade or national accounts. Otherwise, we collect data on imports and exports at current prices from original sources, filling the gaps with interpolations or extrapolations based on trends in nearby polities or those with similar factor endowments. We then deflate these series with country-specific price indexes, mostly based on London prices, adjusted for freights. Finally, we convert all data to current or 1913 dollars (for details see Federico and Tena-Junguito 2016a).

Whenever possible (i.e. if the number of the observations exceeds 25–30), we compute the rate of change of the ith series as w = −β/ψ, where β and ψ are coefficients from a regression (Razzaque et al. 2007) Δ Ln Wt = α + β TIME + ψ lnWt−1 + φ ln Δ Ln Wt−1 + u. Otherwise we use a log-linear specification. In both cases, we test null hypotheses about rates (equal to zero or equal to rates in other periods) with a standard Wald restriction. We compute the cumulated change as Total = [exp(w)*n] − 1.

O’Rourke (2006) reckons that in 1815 exports were equal to the pre-war level in Sweden, one third lower in the United Kingdom and in the United States and half in France. If exports of all other polities declined as much as the French ones, world trade would have been 40% lower than in 1792.

The changes in boundaries before 1913 reduced trade, but the effect was minimal—at most 0.57% in 1860, on the eve of Italian unification. We treat the German Zollverein before 1870 as a single polity.

From 1924 to 1938 trade at constant prices increased by 9.7% if measured at current borders but by 11.1% if estimated at 1913 borders. European exports would have been 2.9% lower than actual ones without boundary changes.

The group of ‘rich’ (or ‘advanced’) countries includes all countries whose GDP per capita exceeded half the British one in 1870—i.e. Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Netherlands, New Zealand, Switzerland, United Kingdom and the United States. The ‘other OECD’ countries are Austria, Greece, Finland, Ireland, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Norway, Portugal, Spain and Sweden. Some Asian and African polities are missing before 1850, and thus the shares of these two continents (and of poor countries) are correspondingly undervalued. However, the bias is very small (the coefficient of correlation between polity shares for the 1830 and the full sample in 1850 is 0.96) and it is a price worth paying to be able to extend the series back to 1830.

Data for 1939–1950 are not available and we prefer to omit from Fig. 3 the war years 1914–1920 because some GDP series at current prices are missing and the figures for belligerent countries are inflated by the inclusion of war-related expenditures.

The increase in export/GDP of the remaining polities would have matched the rise in openness of the sample if their rate of growth of GDP per capita had exceeded 0.9% yearly. This condition was met only by a quarter of the omitted polities from the Maddison (2010) database, and all of them except Germany were very small.

Openness can be computed from 1820 to 1830 for ten polities—the United States, five Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Cuba) and four European ones (France, Denmark, Netherlands and Sweden). The aggregate ratio remained constant around 6%, dragged down by the decline in the American ratio from 7% in 1818 to 5.3% in 1830, but the unweighted average increased from 9.4 to 12.7% and the median from 6.8 to 7.8%.

The long-run σ-convergence among the 29 polities of the sample appears modest (the coefficient of variation declining from over 0.50 in the 1890s to about 0.35–0.4) and it concentrates in the Golden Age when openness was not growing much.

The two series would diverge only if GDP-M and X/GDP have different trends, and this is possible only in the exceptional cases of very open countries with highly unbalanced trade.

We obtain these figures by aggregating all countries in one single ‘world’ rather than weighting country-specific estimates according to their GDP. The comparable estimates for the ‘1870 sample’ are 2.9 and 6.5%.

We use the data on tariff revenue in 1913 from the data-base underlying Federico and Vasta (2015), while for the 2000s we get data from Kee et al. (2009), referring to 2002 (figures in italic) and from the WDI (http://data.worldbank.org accessed Nov 2015), referring to 2007. We compute yearly series of nominal protection for 14 countries in 1870–1974, 11 in 1975–1987 and 8 in 1988–1993 with data on custom revenues from Mitchell (2010, Table G.6).

We compute exports at time t for the ith polity as \( {\text{X}}^{\text{GK}} {\text{t}} = {\text{X}}_{1990}^{\$ } *\left( {{\text{GDP}}_{1990}^{\text{GK}} /{\text{GDP}}_{1990}^{\$ } } \right)*\left( {{\text{X}}^{\text{R}} {\text{t}}/{\text{X}}_{1990}^{\text{R}} } \right) \), where the superscript R refers to local currency at constant prices, GK to Geary-Khamis dollars and $ to dollars at market exchange-rate. Cf. Appendix C for sources of GDP data.

Cf. Statistical Appendix Table S.2. Between 1870–1872 and 1911–1913, the Klasing and Millionis (2014) GDP series increase less than the polity-specific ones in 22 countries out of 25. The three exceptions are Argentina, Belgium, where the difference is minimal, and the Ottoman Empire, which during the period lost all of its Balkan provinces.

References

Anderson, J., & van Wincoop, E. (2004). Trade costs. Journal of Economic Literature, 42, 691–751.

Arkolakis, C., Costinot, A., & Rodriguez-Clare, A. (2012). New trade models, same old gains? American Economic Review, 102, 94–130x.

Bai, J., & Perron, P. (2003). Computation and analysis of multiple structural change models. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 18, 1–22.

Baldwin, R. (2009). The great trade collapse: Causes, consequences and prospects. A VoxEU.org Publication. Geneve and London Graduate Institute and CEPR.

Baldwin, R., & Lopez-Gonzales, J. (2013). Supply-chain trade: A portrait of global patterns and several testable hypotheses. (NBER WP 18957).

Baldwin, R., & Martin, P. (1999). Two waves of globalization: Superficial similarities, fundamental differences. (NBER WP 6904).

Barbieri, K., & Keshk, O. (2012). Correlates of war project trade data set codebook, Version 3.0. Online: http://correlatesofwar.org. Accessed April 2012.

Barbieri, K., Keshk, O. M. G., & Pollins, B. (2009). TRADING DATA: Evaluating our assumptions and coding rules. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 26, 471–491.

Berthelon, M., & Freund, C. (2008). On the conservation of distance in international trade. Journal of International Economics, 75, 310–320.

Bordo, M., Taylor, A. M., & Williamson, J. G. (2003). Globalization in historical perspective. London: University of Chicago Press.

Boz, E., Bussière, M., & Marsilli, C. (2015). Recent slowdown in global trade: Cyclical or structural. In: Hoekman A VoxEU.org eBook, pp. 33–55.

Caliendo, L., & Parro, F. (2015). Estimates of the trade and welfare effects of the NAFTA. Review of Economic Studies, 82, 1–44.

Carrère, C., & Schiff, M. (2005/2006). On the geography of trade. Distance is alive and well. Revue Économique 56, 1249–1274.

Chilosi, D., & Federico, G. (2015). Asian globalisations: Market Integration, trade and economic growth, 1800–1938. Explorations in Economic History, 57, 1–18.

Collier, P., & Dollar, D. (2002). Globalization, growth and poverty. Washington: World Bank.

Constantinescu, C., Mattoo, A., & Ruta, M. (2015). The global trade slowdown cyclical or structural? (World Policy Research Working Paper 7158). World Bank.

Costinot, A., & Rodriguez-Clare, A. (2014). Trade theory with numbers: Quantifying the consequences of globalization. In G. Gopinath, E. Helpman, K. Rogoff (Eds.), Handbook of international economics, Vol. 4. (NBER WP 18896). Amsterdam: Elsevier-North Holland.

Disdier, A.-C., & Head, K. (2008). The puzzling persistence of the distance effect on bilateral trade. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90, 37–48.

Eaton, J., & Kortum, S. (2002). Technology, geography, and trade. Econometrica, 70, 1741–1780.

Eichengreen, B. (2015). Hall of mirrors. The Great Depression, the Great Recession and the uses—and misuses of history. New York: Oxford University Press.

Federico, G. (2004). The growth of world agricultural production, 1800–1938. Research in economic history, 22, 125–181.

Federico, G. (2011). When did the European market integrate? European Review of Economic History, 15, 93–126.

Federico, G. (2012). The Corn Laws in continental perspective. European Review of Economic History, 16, 166–187.

Federico, G., & Tena-Junguito, A. (1991). On the accuracy of foreign trade statistics (1909–35): Morgestern revised. Explorations in Economic History, 28, 259–273.

Federico, G., & Tena-Junguito, A. (2016a). World trade, 1800–1938: A new data-set (EHES Working paper n. 93). http://www.ehes.org/EHES_93.pdf.

Federico, G., & Tena-Junguito, A. (2016b). Population by country 1800–1938. Mimeo.

Federico, G., & Vasta, M. (2015). What do we really know about protection before the Great Depression: Evidence from Italy. Journal of Economic History, 75, 993–1029.

Feenstra, R. (1998). Integration of trade and disintegration of production in the global economy. Journal of economic perspectives, 12, 31–50.

Felbermayr, G., Jung, B., & Larch, M. (2015). The welfare consequences of import tariffs: A quantitative perspective. Journal International economics, 97(2), 295–309.

Findlay, Ronald, & O’Rourke, Kevin H. (2007). Power and plenty: Trade, war, and the world economy in the second millennium. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Glick, R., & Taylor, A. M. (2010). Collateral damage: Trade disruption and the economic impact of war. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92, 102–127.

Grassman, S. (1980). Long term trends in openness of national economies. Oxford Economic Papers, 32, 123–130.

Head, K., & Mayer, T. (2014). Gravity equations: workhorse, toolkit and cookbook. In G. Gopinath, E. Helpman, & K. Rogoff (Eds.), Handbook of international economics (Vol. 4). Amsterdam: Elsevier-North Holland.

Head, K., & Ries, J. (2001). Increasing returns versus national product differentiation as an explanation for the pattern of U.S.-Canada Trade. American Economic Review, 91, 858–876.

Hilberry, R., & Hummels, D. (2014). Trade elasticity parameters for a computable general equilibrium model. In P. B. Dixon & D. W. Jorgenson (Eds.), Handbook of computable general equilibrium modelling (pp. 1213–1269). Amsterdam: Elsevier-North Holland.

Hoeckman, B. (2015). The great trade slowdown: A new normal? CEPR on-line book.

Hugot, J. (2014). Trade costs and the two globalizations: 1827–2012. Mimeo.

Hummels, D. (2007). Transportation costs and international trade in the second era of globalization. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21, 131–154.

Jacks, D. (2005). Intra- and international commodity market integration in the Atlantic economy. Explorations in Economic History, 42, 381–413.

Jacks, D., Meissner, C., & Novy, D. (2006). Trade costs in the first wave of globalization. (NBER WP 12602).

Jacks, D., Meissner, C., & Novy, D. (2011). Trade booms, trade busts and trade costs. Journal of International Economics, 83, 185–201.

Kander, A., Malanima, P., & Warde, P. (2013). Power to the people Energy in Europe over the last five centuries. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kee, H. L., Nicita, A., & Olarreaga, M. (2009). Estimate trade restrictiveness indices. Economic Journal, 119, 172–199.

Klasing, M., & Millionis, P. (2014). Quantifying the evolution of world trade, 1870–1949. Journal of International Economics, 92, 185–197.

Lavallée, E., & Vicard, V. (2013). National borders matter…where one draws the lines too. Canadian Journal of Economics, 46, 135–163.

Maddison, A. (1995). Monitoring the world economy 1820–1992. Paris: OECD Paris.

Maddison, A. (2001). The world economy. A millennial perspective. Paris: OECD Paris.

Maddison Project Data Base (2010). The Maddison-Project, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm, 2013 version. http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/data.htm. Accessed November 2014.

Meissner, C. (2014). Growth from globalization? A view from the very long run. In P. Aghion & S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth (Vol. 2B, pp. 1033–1069). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Mitchell, B. R. (1988). British historical statistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mitchell, B. R. (2010). International Historical Statistics 1750 to 2010. The online database. http://www.palgraveconnect.com/pc/archives/ihs.html. Accessed September 2013.

O’Rourke, K. (2006). The worldwide economic impact of the French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, 1792–1815. Journal of Global History, 1, 123–149.

O’Rourke, K., & Williamson, J. G. (1999). Globalization and history. The evolution of the nineteenth Atlantic economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ossa, R. (2015). Why trade matters. Journal of International Economics, 97(2), 266–277.

Razzaque, M., Osafa-Kwaako, P., & Grynberg, R. (2007). Long-run trend in the relative price: empirical estimation for individual commodities. In R. Grynberg & S. Newton (Eds.), Commodity prices and development (pp. 35–67). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rodrik, D. (1998). Symposium on globalization in perspective: An introduction. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(4), 3–8.

Sharp, P., & Weisdorf, J. (2013). Globalization revisited: Market integration and the wheat trade between North America and Britain from the eighteenth century. Explorations in Economic History, 50, 88–98.

Simonovska, I., & Waugh, M. (2014a). The elasticity of trade: Estimates and evidence. Journal of International Economics, 92, 34–50.

Simonovska, I., & Waugh, M. (2014b). Trade model, trade elasticities and gains from trade. (NBER WP 20495).

Tena-Junguito, A., Lampe, M., & Tamega-Fernandes, F. (2012). How much trade liberalization was there in the world before and after Cobden-Chevalier? Journal of Economic History, 72, 708–740.

Timmer, M. P., Los, B., Stehrer, R., & de Vries, G. J. (2016). An anatomy of the global trade slowdown based on the WIOD 2016 Release. GGDC RESEARCH MEMORANDUM 162. Groningen Growth and Development Centre.

UN Yearbook (ad annum) Yearbook of international trade statistics. New York: United Nations.

World Bank. World development indicators. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators. Accessed February 2014.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by European Research Council Advanced Research Grant (Grant No. 230484) and Spanish Minister of Science and Innovation (Grant Nos. ECO2011-25713, ECO2015/00209/001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Federico, G., Tena-Junguito, A. A tale of two globalizations: gains from trade and openness 1800–2010. Rev World Econ 153, 601–626 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-017-0279-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-017-0279-z