Abstract

In 2011 a working group of the European Society for the Study of Tourette syndrome (ESSTS) developed the first European Guidelines for Tourette syndrome (TS) published in the ECAP journal. After a decade ESSTS now presents updated guidelines, divided into four sections: Part I: assessment, Part II: psychological interventions, Part III: pharmacological treatment and Part IV: deep brain stimulation (DBS). In this paper, we summarise new developments described in the guidelines with respect to assessment and treatment of tics. Further, summary findings from a recent survey conducted amongst TS experts on these same topics are presented, as well as the first European patient representative statement on research. Finally, an updated decision tree is introduced providing a practical algorithm for the treatment of patients with TS. Interestingly, in the last decade there has been a significant shift in assessment and treatment of tics, with more emphasis on non-pharmacological treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Tourette syndrome (TS)Footnote 1 is a neurodevelopmental disorder at the crossroads between neurology, neuropaediatrics, and psychiatry. This is reflected for instance in the notion that tics, the hallmark of TS, are the result of involuntary motor disinhibition on the one hand, but are on the other hand, at least in part, under volitional control and can be voluntarily suppressed.

In 2011 ESSTS working groups have published the first “European Clinical Guidelines for Tourette syndrome and Other Tic Disorders” in the ECAP journal. Structured in four parts, these guidelines summarised the best available evidence combined with best practice expert consensus on the assessment and treatment of TS and related conditions: Part I: assessment [3], Part II: psychological interventions [17], Part III: pharmacological treatment [14], and Part IV: deep brain stimulation (DBS) [9]. The ESSTS guidelines have since then been used throughout Europe and have been cited over 500 times.

In the current special section of ECAP, we present an update of the four parts of the ESSTS guidelines published in 2011, supplemented with a decision tree providing a practical algorithm for the treatment of patients with TS (see Fig. 1) and a patient representative statement on research priorities. All parts together provide a comprehensive guideline that covers assessment and all forms of treatments. Since both empirical research findings and clinical knowledge are important elements of clinical guidelines, these guidelines therefore entail not only a thorough review of the evidence-based literature, but also the results of a survey conducted among ESSTS experts on the assessment and treatment of TS, which are incorporated in each part of the current guidelines.

Algorithm for the treatment of patients with TS based on shared clinician patient decision making (adapted with permission from [14], Springer). TS Tourette syndrome, PT pharmacotherapy, BT behaviour therapy, CBM cannabis-based medicine

Recently the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) has published a systematic review [12] as well as practice guideline recommendations [13]—in which several ESSTS experts participated—on the effectiveness and safety of treatments for tics. Nonetheless, in our opinion, the present updated European clinical guidelines have a raison d'être. Through surveying ESSTS experts on assessment and treatment in both clinical practice and research, we were able to specifically incorporate knowledge and expertise from a large number of European experts into the guidelines. Further, despite overlap between Europe and the US/Canada, there are notable differences with respect to assessment and interventions in clinical practice. This is reflected by differences in health care use and organisation, in patient preferences and in first choice of pharmacological agents, availability and application of behavioural treatments, costs of treatment, and approval status. In the following paragraphs we summarise the most important conclusions formulated in each part of the guidelines.

In Part I: assessment, we have incorporated the newly implemented DSM-5 and ICD-11 criteria. We summarise available literature that includes newly developed tic rating scales and give concrete recommendations for assessments of tics and psychiatric comorbidities in the context of both routine practice and research. In addition, we advice how to differentiate tics and functional “tic-like” movements and “Tourette-like” behaviours [11]. In the DSM-5, the position of tic disorders has remained largely the same as in DSM-IV-TR, classifying TS as a “neurodevelopmental disorder”, alongside attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), intellectual disabilities and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In the ICD-11, in contrast, tic disorders have been removed out of the ICD-10 category “Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence” and reassigned to the movement disorders section. In our opinion, this disregards the growing body of both genetic and clinical evidence that tic disorders are related to developmental and psychiatric disorders rather than to neurological disorders [2, 4]. Furthermore, in our opinion, there is no scientific evidence to support introduction of a subcategory “Infectious or post-infectious tics” (8A05.10) in the category “8A05.1 Secondary tics” [8]. Therefore, we do not recommend assessment of children for Paediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infections (PANDAS)-related TS. Moreover, introduction in ICD-11 of the secondary tics subcategory named “Tics associated with developmental disorders” (8A05.1.1) leaves room for confusion; when a person meets criteria for both tics and ASD or ADHD, he/she can be classified as suffering from either “Tics associated with developmental disorders” (8A05.11), or from TS in combination with ASD. In our opinion, current evidence indicates that tic disorders are by definition neurodevelopmental disorders.

With respect to behavioural interventions, in part II: psychological interventions, we outline substantial progress that has been made since 2011. Most importantly, since then several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been published on habit reversal treatment in both children and adults. As a result, behavioural treatment is currently regarded as the treatment of choice in reducing tics. Accordingly, with this up-date guidelines we changed the order of part II and part III. Further, internet-based modules of established behavioural treatments have been developed to render behaviour therapy more accessible. In addition, adaptations have been made to broaden the focus of behavioural treatment from reducing tic severity only to improving the individual’s overall quality of life.

With respect to pharmacological treatment (part III), most importantly, the antipsychotic agent aripiprazole has been proven effective in the treatment of tics in large-scale RCT [15, 19] and is currently the most frequently prescribed drug in Europe according to the ESSTS survey. During the last decade, three important trends can be noted. First, in contrast to the situation pre-2011, almost all RCTs have been sponsored by pharmaceutical companies which clearly increased the database but also bears the risk of bias [6]. Second, according to the AAN guidelines the traditional Chinese medicine products 5-ling granule and Ningdong granule have now made it to the list of compounds showing moderate confidence in evidence of treatment effects. However, we are not in accordance with this confidence for the following reasons: (i) Investigational Medicinal Product Dossier (IMPD) information that includes safety information of these agents is extremely limited; and (ii) agents contain products such as dried human placenta and therefore are not allowed on the European market. During recent years, several large scale RCTs have been conducted in China [14]. Although they may contain potentially important information, they have been almost exclusively published in Chinese [18]. Therefore, it is impossible to judge upon the quality of these trials for readers not mastering Chinese.

Although some new pharmacological compounds are currently under investigation to treat tics, first results were disappointing: both the vesicular monoamine transport (VMAT) inhibitor deutetrabenazine [16] as well as the inhibitor of the monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) and selective modulator of the endocannabinoid system Lu AG06466 (former ABX-1431) [10] did not meet the primary endpoint of tic reduction in phase 2/3 studies. Therefore, results from RCTs investigating efficacy and safety of ecopipam, a selective antagonist of dopamine D1-type receptors (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01244633), but also nabiximols, a cannabis extract containing tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) at a 1:1 ratio (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03087201), are highly anticipated.

With respect to deep brain stimulation (DBS), in part IV, we present increasing knowledge about efficacy in TS, although numbers and sample sizes of RCTs are still very limited. Reported effects are modest and partly even contradictory with effect sizes of tic improvement between 0.36 and 1.56. European contributions to a meta-analysis [1] and data of the International Tourette syndrome DBS Public Database and Registry [7] have contributed significantly to interpret the heterogeneous results [1, 7].

In order to incorporate clinical knowledge that reflects actual clinical practice in Europe into our revised and updated ESSTS guidelines, between October and November 2019 we conducted an online survey among ESSTS members. This was a follow-up to a prior survey carried out in the context of the 2011 guidelines, which allowed to capture the changes in assessment and treatment practices over the last decade [14]. We received responses from 59 experts from 17 different European countries predominantly from specialised outpatient clinics seeing on average 72 (range 0–600) children, 64 (range 0–666) adolescents, and 40 (range 0–300) adults with tics per year. Of note, experts encompassed child and adolescent psychiatrists (n = 20, 34%), psychologists (n = 11, 19%), adult neurologists (n = 13, 22%), and adult psychiatrists (n = 11, 19%) (several answers missing). Remarkably, 53% (n = 31) of experts conduct both clinical and research work, while 34% (n = 20) work only clinically and 10% (n = 6) are exclusively dedicated to research (several answers missing).

While detailed results of the survey have been added to the four different parts of the updated guidelines, here we briefly highlight the most relevant findings: (i) there is large agreement amongst European TS experts that in clinical practice tic severity assessment is based on clinical judgement complemented with observational and interview data including the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) [5], the latter being the most widely used rating scale for tic assessment both in clinical practice and research; (ii) for the majority of ESSTS experts shared decision-making is common practice in the treatment of patients with TS, aiming to help patients to reach evidence-informed and value-congruent medical decisions; (iii) behavioural therapy was reported to be the first line treatment in both children and adults with tics, but was available in only 57% of centres. In contrast, 65% of experts consider pharmacotherapy when requested; (iv) all over Europe, there is still a substantial lack of trained psychotherapists so that only about half of the patients recommended for behavioural therapy can receive it; (v) as a consequence, internet (known as telemedicine or telehealth) as well as group-based treatment strategies are being introduced in clinical routine practice. Fortunately, different RCTs are currently ongoing investigating the efficacy of different kinds of internet-delivered behavioural therapy; (vi) the majority of experts recommends pharmacotherapy when behavioural therapy has been unsuccessful (72%) or in combination with behavioural therapy for severely affected patients (89%); (vii) compared to 2011, ESSTS experts have shifted from risperidone to mostly using aripiprazole as a first-line therapy followed by risperidone, clonidine, guanfacine (children) and topiramate (adults), respectively; (viii) remarkably, haloperidol, although being the only officially licenced drug for tic treatment in most European countries, is no longer used as a preferred drug by European experts (used by 6 (10%) experts in children/adolescents and 7 (12%) in adults, respectively); (ix) ESSTS experts consider DBS only in carefully selected and otherwise treatment-refractory patients corresponding to fewer than 3% of all patients. Although introduced already in 1999, DBS is still offered in only about 25% of highly specialised TS clinics.

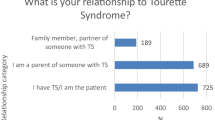

Finally and uniquely, a paper by patients representatives in Europe who conducted a world-wide survey among patient advocacy groups, describes the patient perspective on different research topics. Unsurprisingly, three quarters of the 2000 respondents indicated that they would prefer research into the topic “how to treat TS and/or decrease symptoms”.

In conclusion, our revised ESSTS guidelines contain updated information on recent developments on assessment and treatment of TS, combined with a patient representative statement, which expresses the close and fruitful collaboration between advocacy groups and experts in the ESSTS community.

Notes

We use the term TS in these guidelines, wherever information also applies to other forms of tic disorders. Only if there are substantial, well-known differences between TS and other forms of tic disorders, we use TS or other terms, e.g. transient or chronic motor tic disorder.

References

Baldermann JC, Schüller T, Huys D, Becker I, Timmermann L, Jessen F, Visser-Vandewalle V, Kuhn J (2016) Deep brain stimulation for Tourette-Syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Stimul 9:296–304

Brainstorm C, Anttila V, Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Walters RK, Bras J, Duncan L, Escott-Price V, Falcone GJ, Gormley P, Malik R, Patsopoulos NA, Ripke S, Wei Z, Yu D, Lee PH, Turley P, Grenier-Boley B, Chouraki V, Kamatani Y, Berr C, Letenneur L, Hannequin D, Amouyel P, Boland A, Deleuze JF, Duron E, Vardarajan BN, Reitz C, Goate AM, Huentelman MJ, Kamboh MI, Larson EB, Rogaeva E, St George-Hyslop P, Hakonarson H, Kukull WA, Farrer LA, Barnes LL, Beach TG, Demirci FY, Head E, Hulette CM, Jicha GA, Kauwe JSK, Kaye JA, Leverenz JB, Levey AI, Lieberman AP, Pankratz VS, Poon WW, Quinn JF, Saykin AJ, Schneider LS, Smith AG, Sonnen JA, Stern RA, Van Deerlin VM, Van Eldik LJ, Harold D, Russo G, Rubinsztein DC, Bayer A, Tsolaki M, Proitsi P, Fox NC, Hampel H, Owen MJ, Mead S, Passmore P, Morgan K, Nothen MM, Rossor M, Lupton MK, Hoffmann P, Kornhuber J, Lawlor B, McQuillin A, Al-Chalabi A, Bis JC, Ruiz A, Boada M, Seshadri S, Beiser A, Rice K, van der Lee SJ, De Jager PL, Geschwind DH, Riemenschneider M, Riedel-Heller S, Rotter JI, Ransmayr G, Hyman BT, Cruchaga C, Alegret M, Winsvold B, Palta P, Farh KH, Cuenca-Leon E, Furlotte N et al (2018) Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap8757

Cath DC, Hedderly T, Ludolph AG, Stern JS, Murphy T, HartmannCzernecki AV, Robertson MM, Martino D, Munchau A, Rizzo R, Group EG (2011) European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part I: assessment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 20:155–171

Hirschtritt ME, Lee PC, Pauls DL, Dion Y, Grados MA, Illmann C, King RA, Sandor P, McMahon WM, Lyon GJ, Cath DC, Kurlan R, Robertson MM, Osiecki L, Scharf JM, Mathews CA (2015) Lifetime prevalence, age of risk, and genetic relationships of comorbid psychiatric disorders in Tourette syndrome. JAMA Psychiat 72:325–333

Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, Ort SI, Swartz KL, Stevenson J, Cohen DJ (1989) The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 28:566–573

Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, Schroll JB, Bero L (2018) Industry sponsorship and research outcome: systematic review with meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 44:1603–1612

Martinez-Ramirez D, Jimenez-Shahed J, Leckman JF, Porta M, Servello D, Meng FG, Kuhn J, Huys D, Baldermann JC, Foltynie T, Hariz MI, Joyce EM, Zrinzo L, Kefalopoulou Z, Silburn P, Coyne T, Mogilner AY, Pourfar MH, Khandhar SM, Auyeung M, Ostrem JL, Visser-Vandewalle V, Welter ML, Mallet L, Karachi C, Houeto JL, Klassen BT, Ackermans L, Kaido T, Temel Y, Gross RE, Walker HC, Lozano AM, Walter BL, Mari Z, Anderson WS, Changizi BK, Moro E, Zauber SE, Schrock LE, Zhang JG, Hu W, Rizer K, Monari EH, Foote KD, Malaty IA, Deeb W, Gunduz A, Okun MS (2018) Efficacy and safety of deep brain stimulation in Tourette syndrome: the international Tourette syndrome deep brain stimulation public database and registry. JAMA Neurol 75:353–359

Martino D, Schrag A, Anastasiou Z, Apter A, Benaroya-Milstein N, Buttiglione M, Cardona F, Creti R, Efstratiou A, Hedderly T, Heyman I, Huyser C, Madruga M, Mir P, Morer A, Mol Debes N, Moll N, Müller N, Müller-Vahl K, Munchau A, Nagy P, Plessen KJ, Porcelli C, Rizzo R, Roessner V, Schnell J, Schwarz M, Skov L, Steinberg T, Tarnok Z, Walitza S, Dietrich A, Hoekstra PJ (2021) Association of Group A streptococcus exposure and exacerbations of chronic tic disorders: a multinational prospective cohort study. Neurology 96:e1680–e1693

Muller-Vahl KR, Cath DC, Cavanna AE, Dehning S, Porta M, Robertson MM, Visser-Vandewalle V, Group EG (2011) European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part IV: deep brain stimulation. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 20:209–217

Müller-Vahl KR, Fremer C, Beals C, Ivkovic J, Loft H, Schindler C (2021) Monoacylglycerol Lipase Inhibition in Tourette Syndrome: A 12-Week, Randomized, Controlled Study. Mov Disord. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.28681

Müller-Vahl KRR, Veit; Münchau, Alexander (2020) Tourette-Syndrom: Häufig eine Fehldiagnose. Deutsche Aerzteblatt 117

Pringsheim T, Holler-Managan Y, Okun MS, Jankovic J, Piacentini J, Cavanna AE, Martino D, Muller-Vahl K, Woods DW, Robinson M, Jarvie E, Roessner V, Oskoui M (2019) Comprehensive systematic review summary: treatment of tics in people with Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders. Neurology 92:907–915

Pringsheim T, Okun MS, Müller-Vahl K, Martino D, Jankovic J, Cavanna AE, Woods DW, Robinson M, Jarvie E, Roessner V, Oskoui M, Holler-Managan Y, Piacentini J (2019) Practice guideline recommendations summary: treatment of tics in people with Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders. Neurology 92:896–906

Roessner V, Plessen KJ, Rothenberger A, Ludolph AG, Rizzo R, Skov L, Strand G, Stern JS, Termine C, Hoekstra PJ, Group EG (2011) European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part II: pharmacological treatment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 20:173–196

Sallee F, Kohegyi E, Zhao J, McQuade R, Cox K, Sanchez R, van Beek A, Nyilas M, Carson W, Kurlan R (2017) Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial demonstrates the efficacy and safety of oral aripiprazole for the treatment of Tourette’s disorder in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 27:771–781

TEVA (2020) Teva announces registration trials of deutetrabenazine in pediatric patients with Tourette syndrome did not meet the primary endpoint

Verdellen C, van de Griendt J, Hartmann A, Murphy T, Group EG (2011) European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part III: behavioural and psychosocial interventions. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 20:197–207

Yang C, Hao Z, Zhang LL, Zhu CR, Zhu P, Guo Q (2019) Comparative efficacy and safety of antipsychotic drugs for tic disorders: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Pharmacopsychiatry 52:7–15

Yoo HK, Joung YS, Lee JS, Song DH, Lee YS, Kim JW, Kim BN, Cho SC (2013) A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with Tourette’s disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 74:e772-780

Acknowledgements

We thank all TS patients and TS Advocacy Groups for their contribution in the functioning of ESSTS, participation in research as well as having supported these guidelines with a patient representative statement.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception: KRMV, DCC; literature search: KRMV, DCC, NS; writing of the first draft: KRMV, DCC, NS; revision: KRMV, DCC, NS, AH, PJH, CV, VR.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

KMV has received financial or material research support from EU (FP7-HEALTH-2011 No. 278367, FP7-PEOPLE-2012-ITN No. 316978) DFG: GZ MU 1527/3-1 and GZ MU 1527/3-2, BMBF: 01KG1421, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Tourette Gesellschaft Deutschland e.V. Else-Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung, GW pharmaceuticals, Almirall Hermal GmbH, Abide Therapeutics, and Therapix Biosiences. She has received consultant's honoraria from Abide Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Bionorica Ethics GmbH, CannaMedical Pharma GmbH, Canopy Grouth, Columbia Care, CTC Communications Corp., Demecan, Eurox Deutschland GmbH, Global Praxis Group Limited, IMC Germany, Lundbeck, Sanity Group, Stadapharm GmbH, Synendos Therapeutics AG, and Tilray. She is an advisory/scientific board member for CannaMedical Pharma GmbH, Bionorica Ethics GmbH, CannaXan GmbH, Canopy Growth, Columbia Care, IMC Germany, Leafly Deutschland GmbH, Sanity Group, Syqe Medical Ltd., Therapix Biosciences Ltd., and Wayland Group. She has received speaker’s fees from Aphria Deutschland GmbH, Almirall, Cogitando GmbH, Emalex, Eurox Deutschland GmbH, Ever pharma GmbH, Meinhardt Congress GmbH, PR Berater, Spectrum Therapeutics GmbH, Takeda GmbH, Tilray, Wayland Group. She has received royalties fromDeutsches Ärzteblatt, Der Neurologie und Psychiater, Elsevier, Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft Berlin, and Kohlhammer. She served as a guest editor for Frontiers in Neurology on the research topic “The neurobiology and genetics of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: new avenues through large-scale collaborative projects”, is an associate editor for “Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research” and an Editorial Board Member of “Medical Cannabis and Cannabinoids” und “MDPI-Reports” and a Scientific board member for “Zeitschrift für Allgemeinmedizin”. NSZ has no conflicts to declare. DC has received financial support from EU (FP7-HEALTH-2011 No. 278367; FP7-PEOPLE-2012-ITN No. 316978), from VCVGz, and from Tourette Association of America. AH has received financial or material research support from the Association Française pour le syndrome de Gilles de la Tourette (AFSGT). He has received consultant's honoraria from Lundbeck and Noema Pharma. VR has received payment for consulting and writing activities from Lilly, Novartis, and Shire Pharmaceuticals, lecture honoraria from Lilly, Novartis, Shire Pharmaceuticals, and Medice Pharma, and support for research from Shire Pharmaceuticals and Novartis. He has carried out clinical trials in cooperation with the Novartis, Shire, Servier and Otsuka companies. PJH has received a honorarium for an advisory board meeting of Shire. NSZ and CV have no conflicts to declare.

Additional information

This article is part of the focused issue “Update of the European clinical guidelines for Tourette Syndrome and other tic disorders”.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Müller-Vahl, K.R., Szejko, N., Verdellen, C. et al. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders: summary statement. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31, 377–382 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01832-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01832-4