Abstract

Psychosocial care systems have been designed so that specific problems are treated by specific care types. There is insufficient evidence as to which problem types are actually presented to the various care types. This study assessed types and severity of problems among children and adolescents upon enrolment in psychosocial care, compared to children not enrolled; also outcomes after 3 and 12 months, overall and per care type. We obtained data on a cohort of 1382 Dutch children aged 4–18 years (response rate 56.6%), included upon enrolment in psychosocial care, and on 443 not-enrolled children (response rate 70.3%), all from one region. Results showed that enrolled children had more problems than children not enrolled in care. In child and adolescent mental healthcare (CAMH), relatively many children had internalizing problems, and in child and adolescent social care (CASC) relatively many children had externalizing, parenting, family and multiple problems. Regardless of the type of problem, care duration in preventive child healthcare (PCH) was relatively short; and in CASC and CAMH longer. After 3 and 12 months, rates of problem solution were highest in PCH. These rates were also substantial among children not in care. To conclude, our findings show that the system of psychosocial care functions as intended regarding the distribution of problems across care types. Extended demarcation of clients by problem type and severity towards type and contents of care may further improve the system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children and their families enrol in psychosocial care because of various child and family problems [1, 2]. However, evidence is lacking as to which types of problems are presented to which types of psychosocial care, even though the idea behind the system of psychosocial care would seem self-evident [3]. Evidence is also lacking as to whether care outcomes vary depending on the alignment of type of problems with type of psychosocial care. Such knowledge is needed to optimize the access of children and adolescents to psychosocial care, to deliver care that is need-oriented, and to improve care outcomes [4,5,6,7].

Systems for psychosocial care have been designed so that specific care types focus on specific child and family problems, depending on levels of problem severity and co-occurrence of problems in the social and/or economic context of the child [8,9,10]. For example, in The Netherlands, preventive child healthcare (PCH) focuses on mild child and family problems, referring children and families with more severe problems. Specialized child and adolescent mental healthcare (CAMH) provides care for children with more severe psychosocial problems and psychiatric disorders. Child and adolescent social care (CASC), in addition to dealing with children’s psychosocial problems, focuses on problems in the social and economic context that could impede or threaten the child’s development, problems such as poor parenting and unhealthy family functioning [3, 8].

Types of psychosocial care have thus been delineated by design, but there is insufficient evidence as to whether this delineation is realized in practice. The few available studies suggest at least some overlap in the types of problems addressed by the various care types. However, these previous studies have addressed only the child’s problems, without considering problems in their social and economic context [3, 11,12,13,14]. Moreover, there is little evidence on the effectiveness of the design itself: which problems could best be referred to which types of psychosocial care.

The aim of our study was thus to assess the types and severity of problems upon enrolment in psychosocial care, i.e. child, parenting and family problems, and compare these to problems of children and adolescents not enrolled in psychosocial care. Next, we assessed outcomes, i.e. care duration and problem solution, after 3 and 12 months.

Methods

Study design

We used one-year follow-up data from TakeCare, a large prospective cohort study of children aged 4–18 in the northeast of The Netherlands [8]. TakeCare has been designed to investigate the trajectories and outcomes of children receiving psychosocial care and consists of a care cohort of children enrolling in psychosocial care, and a reference cohort of children not in care. Between April 2011 and April 2013, parents/caregivers of children aged 4–18 years, along with children aged 12 years and over, were invited to participate in TakeCare. The Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen evaluated the design of the study, and approved it without requiring full assessment. Informed consent was obtained from all participating respondents [8].

Sample and procedure

For the care cohort, 2664 children and their parents/caregivers were recruited via PCH, CASC and CAMH, the main providers of psychosocial care for children and adolescents in The Netherlands. At the time of our study, children entered psychosocial care via either their general practitioner, the youth care office, or PCH [15]. General practitioners and doctors and nurses in PCH provide light psychosocial support to children and their families. In case of more severe problems they refer children to specialized care, either to CASC, primarily staffed by child (social) workers, or to CAMH, primarily staffed by child psychologists and psychiatrists [3]. See Table 1 for a detailed description of the care types.

Children with insufficient understanding of Dutch, living outside the northern region, or following special education because of intellectual disability, were excluded (N = 223). Of the eligible (either child and/or parent) 2441 respondents, 1382 participated (response 56.6%). Differences between respondents and non-respondents were small regarding characteristics known to influence enrolment and outcomes and available for non-respondents: age, gender, degree of urbanization (i.e. rural versus urban based on density of living addresses per zip code), and psychosocial problems. For these Cohen’s effect sizes ranging from 0.01 (age) to 0.12 (degree of urbanization) [8, 17, 18].

For the reference cohort a stratified random sample of 1025 school children and their parents was approached. The sample was obtained via five primary schools, two secondary schools, and one school for intermediate vocational education. Thereby the distribution of children across the study region according to age, gender, socioeconomic position, and degree of urbanization was taken into account. Of these children, 77 were excluded using the same exclusion criteria as with the care cohort. Of the eligible 948 respondents, 666 participated (70.3%). Differences between respondents and non-respondents were small regarding age, gender, degree of urbanization, and psychosocial problems, with effect sizes ranging from 0.02 (psychosocial problems) to 0.08 (degree of urbanization) [8]. Children who had had contact with psychosocial care in the past 6 months were excluded. This resulted in a reference cohort of 443 participants.

Data were obtained from parents/caregivers and adolescents via web-based or paper questionnaires at three moments. If required, we provided assistance in filling out the questionnaire. The baseline measurement (T1) followed directly after entry into the study, which was, for the care cohort, at the moment of the child’s enrolment. The second (T2) and third (T3) questionnaires were sent 3 and 12 months after the first questionnaire, respectively. The loss to follow-up at T2 and T3 was 6.9 and 8.8% for the care cohort and 2.0 and 2.2% for the reference cohort, respectively [8].

Measures

Types of problems concerned child, parenting and family problems upon entry into the study (T1), after three months (T2) and after one year (T3). Child problems concerned internalizing and externalizing problems measured using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [19,20,21]. The SDQ consists of 25 items describing positive and negative attributes of children with regard to emotional problems, behavioral problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial behavior. We measured internalizing problems as the sum of ten items related to emotional and peer problems [Cronbach’s α parents = 0.78 (T1, T2, T3), adolescents = 0.75 (T1), 0.76 (T2), 0.73 (T3)], and externalizing problems as the sum of ten items related to behavioral problems and hyperactivity [Cronbach’s α parents = 0.83 (T1, T2, T3), adolescents = 0.74 (T1), 0.76 (T2), 0.73 (T3)] [22]. Scores were (a) dichotomized as ‘problems’ if either the parent score or the adolescent score was increased, versus ‘no problems’, and (b) counted as change in mean severity (ranges 0–20).

Parenting problems were measured using total parent scores on the nine-item version of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ) [23]. The APQ includes a five-point Likert scale on the domains poor supervision, inconsistent disciplining and positive parenting (maximum of three missing items, Cronbach’s α = 0.66 (T1, T2), 0.69 (T3)). The total APQ scale was dichotomized into ‘problems’ (score 2.25–5), based on the 20% highest scores in the total reference cohort on T1 and otherwise into ‘no problems’, i.e. reflecting the SDQ cut-off points. Scores were also summed per measurement, leading to changes in severity between measurements (range 1–5).

Family problems were measured using the General Functioning Scale (GF) of the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD) [24, 25]. Using 12 items, the scale included the dimensions problem solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness and involvement, and behavioural control. Parents rated their agreement on a four-point scale from ‘totally disagree’ to ‘totally agree’ (maximum of two missing items, Cronbach’s α = 0.87 (T1, T2), 0.83 (T3)). The GF was (a) dichotomized into ‘problems’, i.e. unhealthy family functioning, or ‘no problems’, i.e. healthy family functioning, and (b) counted as change in mean severity (range 1–4) [26].

Number of problems was measured by combining the dichotomized scores on internalizing, externalizing, parenting and family problems, resulting in five categories ranging from problems in no domain to problems in four domains. For example, a child with both internalizing and externalizing problems, and a child with both internalizing problems and parents who had parenting problems fell in the second category.

Types of psychosocial care referred to the psychosocial care service by which children entered this study, categorized as ‘PCH’, ‘CASC’ or ‘CAMH’. Children in the reference cohort were categorized as ‘Not in care’.

Duration of care as a process-outcome was included and defined as (0) ‘0–3 months’, (1) ‘> 3 months-1 year’, and (2) ‘> year’, based on information from adolescents, and from the parents if no child information was available.

Outcomes after three and twelve months referred to problem solution with resolved problems and change in severity per type of problem (internalizing, externalizing, parenting and family problems). Resolved problems referred to a change from a ‘problem’ score at T1 to a ‘no problems’ score at T2 and T3, respectively. Change in problem severity referred to a change between T1, T2 and T3, respectively.

Background characteristics included age, gender, ethnicity, psychosocial care use in the past six months, parental educational level, and family composition (T1). Age was categorized as 4–11, and 12–19, as in the Dutch educational system the primary school age includes ages 4–11; and secondary school age is from 12 years onwards; the child psychosocial care system is focused on children up to 18 years old. Ethnicity was defined as either Dutch or non-Dutch (the child and/or one of the parents was foreign-born). Psychosocial care use in the past six months was measured with the Questionnaire Intensive Care for Youth (QUINCY) [27,28,29,30]. Parents and adolescents reported whether they had used care because of the child’s psychosocial problems, and if so, which type(s) and by which professional. Past use of care was defined as the use of professional care for psychosocial problems of the child during the past 6 months.

Parental educational level was based on the highest educational level achieved by either one of the parents/caregivers [31]. Family composition was assessed by asking the parent and the adolescent with whom the child lived. This was categorized into ‘biological two-parent family’ and ‘other’ (e.g., living with one parent, a foster family or living in a residential care facility).

Analyses

First, we described the characteristics of the cohorts. Second, we assessed the types of problems of children being enrolled, as compared to children not enrolled, in psychosocial care, per type of care enrolled in. Third, we assessed the duration of care and problem solution (removal and reduction of severity of problems) between the types of care, per type of problem. We performed the analyses on the reduction of severity of problems using Generalized Linear Mixed Modelling in SAS (http://www.sas.com), taking into account the hierarchical nature of the pre-post data. We repeated all analyses after the exclusion of those receiving psychosocial care before T2 or T3 from the group of children and adolescents not enrolled in care.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

The majority of the enrolled children were 4–11 years old; a slight majority were male and living in other than a biological two-parent family. Among children aged 12–19 years, parents reported psychosocial problems more frequently than did children. Of the children not enrolled in care, the majority were also 4–11 years of age; a large majority were female and lived with their biological parents. Contrary to the enrolled group, children aged 12–19 years in the non-enrolled group reported problems more frequently than did parents (Table 2). For children aged 4–11 years, no child report was available due to their young age.

The distribution of age and gender over the three care types showed that children enrolled in PCH were mainly 4–11 years old with an even distribution for gender. In CASC more children were 12–19 years old and female, and in CAMH more were 4–11 years old and male (Table 3).

Types of problems upon enrolment

Children enrolled in psychosocial care most often had internalizing problems, followed by externalizing problems, family problems and parents with parenting problems (Table 3). They usually had one or two problems. Children not enrolled in psychosocial care usually had no child, parenting or family problems. If they had a problem, it was most frequently only one problem, and involved internalizing problems or parenting problems. One problem mostly concerned internalizing problems (not in care: 38.0%; enrolled in care: 58.3%). Two problems mainly concerned internalizing and externalizing problems (not in care: 28.6%; enrolled in care: 58.0%). Three problems mainly concerned internalizing and externalizing with parenting problems (not in care: 66.7%) or with family problems (enrolled in care: 25.5%) (data not shown).

Regarding the link between type of problems and type of care enrolled in, internalizing problems occurred relatively most frequently in CAMH. Externalizing problems, parenting problems and family problems occurred relatively most frequently in CASC. Regarding the number of problems, three or four problems occurred relatively most frequently in CASC and two problems most frequently in CAMH. Finally, no problems or only one problem occurred most frequently in PCH.

Outcomes

Results on outcomes showed that for children and adolescents with any problem upon enrolment, care duration was short in PCH and longer in CASC and CAMH (Table 4). Regarding the other outcomes, children not in care as well as children in PCH showed the highest frequency of resolved problems, i.e. no longer having any problem, both after three and twelve months.

Results per type of problems upon enrolment showed that for internalizing problems, care duration was also short in PCH and longer in CASC and CAMH. Internalizing problems were most frequently resolved among children not in care and in PCH, both after three and twelve months. Decrease in severity of internalizing problems was highest in PCH. Regarding externalizing problems upon enrolment, no significant differences occurred between the care types or between those enrolled or not enrolled in care.

For parenting problems, care duration was also shortest in PCH and longer in CASC and CAMH. No significant differences emerged between the four groups in the frequency of parenting problems resolved. Decrease of severity of parenting problems was highest in PCH, both after three and twelve months. Finally, regarding family problems, no significant differences emerged between groups.

Exclusion of children and adolescents receiving psychosocial care before T2 or T3 from the group not enrolled in care (n = 130) yielded somewhat greater differences between the children enrolled in care and the group not enrolled in care, but without affecting the general pattern (not shown).

Discussion

In general our findings confirm the principles behind the system of psychosocial care for children and adolescents. Children enrolled in PCH had mild problems compared to children in CASC and CAMH. In CAMH, relatively many children had internalizing problems, and in CASC relatively many children had externalizing, parenting, family and multiple problems (child problems and problems related to the child’s context, respectively). Further, care duration was relatively short in PCH and longer in CASC and CAMH. Finally, problems were resolved most often in PCH and among children not in care.

These findings confirming the principles of the system are in line with the limited previous findings. First, PCH treats mild problems, and CASC and CAMH more severe problems. This may explain the short care duration and greater problem solution in PCH compared to CASC and CAMH [32, 33]. More severe problems—most likely also more complex, more persistent and combined with other problems—can be expected to be more difficult to treat and, therefore, to require longer treatment [32, 33]. Second, our study shows that, compared to CAMH, CASC focuses more on the social and/or economic context of the child, as well as on the child’s problems. This confirms, for example, the available evidence that parental divorce has a stronger association with the use of CASC than with the use of CAMH [3]. The system thus seems to perform as intended regarding the distribution of problems across care types. Third, children in PCH are much younger than in the other types of care, due to the focus of PCH on primary schools. This younger age may contribute to differences in outcomes.

Our study showed that some children enrolled in care did not seem to have problems—13%, and that some children not enrolled in care did seem to have problems—35%; this confirms previous findings [2, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. The first observation—children enrolled ‘without problems’—might imply that other reasons for enrolment occurred, in particular the existence of a threat of developing problems or other care needs, as in cases of parental divorce with strong conflicts or previous hospitalization [5, 32, 36]. It is also possible that problems which existed initially were resolved rather quickly, before the SDQ was scored [39]. Finally, the observation might also simply indicate overtreatment [2, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. In any case, the first explanation holds. The second observation—children with problems not enrolled in care—may imply undertreatment caused by barriers to access to care, barriers involving problem recognition, help seeking or referral [30, 41,42,43,44,45]. It might be that some of these barriers are resolved later on. This is supported by our finding that 29% of the children not enrolled initially contacted a professional, usually the general practitioner, for light psychosocial support after 3 or after 12 months. An explanation may be that problems are not recognized by the parents. The finding that adolescents in the non-enrolled group reported higher problem levels than their parents, and that the contrary holds for enrolled adolescents, somewhat supports this explanation. It may also be that children with problems not enrolled in care consider themselves able to cope with their problems, or do not really consider them problematic [35, 36, 46, 47]. Further research is needed to disentangle these explanations.

Regarding outcomes, we found that the decrease in problem severity was relatively strong for clients enrolled with internalizing or parenting problems in PCH compared to those enrolled in CASC and CAMH. An explanation for this may be that problems in PCH less often have other concomitant psychosocial problems, compared to CASC and CAMH. Especially in CASC, problems are often multiple, i.e. almost 40% of the children enrolled in CASC had three or four problems. Singular problems are more likely to be easily changed than are multiple problems. Resolving problems may, therefore, take more time in CASC and CAMH. These findings on outcomes also confirm that the system works as intended: light and short care for mild and singular problems that are easily resolved, and specialized and longer care for severe and concomitant problems that are more persistent [48, 49].

Between clients of the three care types and those not enrolled in care with externalizing or family problems, our study showed a substantial overlap in outcomes. In addition, for clients with internalizing or parenting problems, outcomes were rather similar in CASC and in CAMH. This implies that the system as designed and realized does not highly affect problem solution; e.g. child context problems are not resolved more often in CASC than in CAMH. As far as we know this is the first study to compare several outcomes between various care types with the problem type upon enrolment. Further research is needed, for example, on the types of interventions offered within each care type, to determine which type of care best applies to which type of problem [9, 10].

Regarding problem solution, we found substantial but by far not complete reductions in problem rates, i.e. 35–62% after 12 months, confirming previous research [1, 5, 50, 51]. An explanation might be that treatment is not always aimed at problem solution, but sometimes just at making problems more manageable, as not all disorders can be cured [52]. We also found substantial problem reduction among children not in care—e.g. 43% for any problem after 12 months. This again confirms earlier findings [53, 54], but with more robust data. Our finding suggests that problems among children and adolescents not enrolled in care resolve spontaneously more easily because they are less severe and usually not accompanied by other psychosocial problems. In addition, our study showed that children not enrolled in care live in a more favourable context, such as with their two biological parents, with parents with relatively higher educational levels, and more often off Dutch origin (for comparable findings, see [41, 55, 56]). These findings on outcomes might also be seen to suggest that treatment is, on average, only to some extent effective, with some children and/or parents reaping more benefit than others [1, 50]. Insight into the impact of care on other outcomes, such as coping with problems, could lead to a better understanding of this issue.

Strengths and limitations

This study has considerable strengths. First, we were able to make longitudinal comparisons between children and adolescents enrolled in care and those not enrolled, with high retention and in a large sample. Second, we were able to include all children and adolescents in a well-defined catchment area, providing an inclusive overview of all types of psychosocial care.

Our study also had some limitations. First, we had a considerable non-response upon entry. However, differences between respondents and non-respondents were small, decreasing the likelihood of selection bias [8]. Second, the observational nature of this study limits its potential causal inferences on outcomes of care. Third, although we included both parents and adolescents reported data, we did not have adolescents’ reports for some problem domains, such as for parenting and family problems.

Implications

Our study provides a first sketch of the association between problems upon enrolment, care types, and outcomes. Essentially, we found that the system of psychosocial care seems to perform as intended regarding the distribution of problems across care types. Our findings also suggest several starting points for the improvement of the system, e.g. regarding (1) children enrolled in care without problems and children not enrolled in care with problems, (2) overlap in outcomes between care types, and (3) only partial solution of problems.

The first issue has to do with improving the process of enrolment in care. We particularly need to disentangle the reasons why some children without problems enrol in care, and others with problems do not, to show whether or not this is a desired situation. A related issue is to further disentangle why adolescents in the non-enrolled group scored higher on psychosocial problems compared to their parents, and why this was the opposite in the enrolled group, and whether this difference is related to the process of enrolment in care.

The second issue, overlap in outcomes, calls for further research on the specific interventions offered in each type of care to assess whether or not the type of care makes any difference. For example, internalizing problems caused by trauma probably require other interventions than those caused by phobia [57]. Such research may also indicate to what extent care types are (dis)similar and whether the intentions of the system should become more specific and demarcated (i.e., CAMH specializes in the child’s problems; and CASC specializes in the child’s context). In addition, further research should explain to what extent the solution of one problem type, affects the solution of another problem type.

The third issue shows a need for further research into the impact of psychosocial care on other outcomes, such as coping strategies, or impairments in societal participation of children and their caretakers [57]. This could also include an assessment of underlying characteristics affecting prognosis, in multivariate analyses. Such research could further improve our understanding of the role and importance of psychosocial care for children and their families.

Finally, our findings need confirmation by and comparison with other systems of psychosocial care for children. Apparently such systems vary, though comparative research throughout the European Union shows a rather striking resemblance across countries [58]. This suggests a major global change in improving care for children and adolescents [2].

References

Garland AF, Accurso EC, Haine-Schlagel R, Brookman-Frazee L, Roesch S, Zhang JJ (2014) Searching for elements of evidence-based practices in children’s usual care and examining their impact. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 43:201–215. doi:10.1080/15374416.2013.869750

Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P (2007) Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet 369:1302–1313. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7

Reijneveld SA, Wiegersma PA, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Vollebergh WA, Jansen DE (2014) Adolescents’ use of care for behavioral and emotional problems: types, trends, and determinants. PLoS One 9:1–11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093526

Axford N, Little M, Morpeth L, Weyts A (2005) Evaluating children’s services: recent conceptual and methodological developments. Brit J Soc Work 35:73–88. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bch163

Fernandez E (2007) Supporting children and responding to their families: capturing the evidence on family support. Child Youth Serv Rev 29:1368–1394. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.05.012

Vanhaecht K, Panella M, Van Zelm R, Sermeus W (2010) An overview on the history and concept of care pathways as complex interventions. Int J Care Pathw 14:117–123. doi:10.1258/jicp.2010.010019

Metselaar J, Van Yperen TA, Van den Bergh PM, Knorth EJ (2015) Needs-led child and youth care: main characteristics and evidence on outcomes. Child Youth Serv Rev 58:60–70. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.09.005

Verhage V, Noordik E, Knorth EJ, Reijneveld SA (2014) Cohort profile: tracing achievements, key processes and efforts in professional care for Children and Adolescents research; TAKECARE. Int J Epidemiol. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu237 (published online ahead of print)

Evenboer K, Huyghen A, Tuinstra J, Reijneveld S, Knorth E (2014) Opening the black box toward classifying care and treatment for children and adolescents with behavioral and emotional problems within and across care organizations. Res Soc Work Pract. doi:10.1177/1049731514552049 (published online ahead of print)

Evenboer K, Huyghen A, Tuinstra J, Knorth E, Reijneveld S (2016) What’s the difference? Using descriptors to classify the care provided to children and adolescents with behavioral and emotional problems. Child Youth Serv Rev 61:353–358. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.01.010

Chavira DA, Garland A, Yeh M, McCabe K, Hough RL (2009) Child anxiety disorders in public systems of care: comorbidity and service utilization. J Behav Health Serv Res 36:492–504. doi:10.1007/s11414-008-9139-x

Cuffe SP, Moore CG, McKeown R (2009) ADHD and health services utilization in the national health interview survey. J Atten Disord 12:330–340. doi:10.1177/1087054708323248

Wu P, Katic BJ, Liu X, Fan B, Fuller CJ (2010) Mental health service use among suicidal adolescents: findings from a US national community survey. Psychiatr Serv 61:17–24. doi:10.1176/ps.2010.61.1.17

Villabø MA, Cummings CM, Gere MK, Torgersen S, Kendall PC (2013) Anxious youth in research and service clinics. J Anxiety Disord 27:16–24. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.09.003

Harder AT, Zeller M, López M, Köngeter S, Knorth EJ (2013) Different sizes, similar challenges: out of home care for youth in Germany and The Netherlands. Psychosoc Interv 22:203–213. doi:10.5093/in2013a24

Evenboer KE (2015) A taxonomy of care for children and adolescents with behavioural and emotional problems: development and application. Dissertation, University of Groningen: http://www.rug.nl/research/portal/publications/pub(33de07b6-de7b-4c81-a958-5945b220576b).html. Accessed 13 Oct 2017

Den Dulk CJ, Van de Stadt H, Vliegen JM (1992) Een nieuwe maatstaf voor stedelijkheid: De omgevingsadressendichtheid [A new measure for degree of urbanisation: the address density of the surrounding area]. Maandstatistiek Bevolking (CBS). 40:14–27

Reijneveld SA, Veenstra R, de Winter AF, Verhulst FC, Ormel J, de Meer G (2010) Area deprivation affects behavioural problems of young adolescents in mixed urban and rural areas: the TRAILS study. J Adolesc Health 46:189–196

Crone MR, Vogels AG, Hoekstra F, Treffers PD, Reijneveld SA (2008) A comparison of four scoring methods based on the parent-rated strengths and difficulties questionnaire as used in the Dutch preventive child health care system. BMC Public Health 8:106–114. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-106

Muris P, Meesters C, van den Berg F (2003) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 12:1–8. doi:10.1007/s00787-003-0298-2

Van Widenfelt BM, Goedhart AW, Treffers PD, Goodman R (2003) Dutch version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ). Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 12:281–289. doi:10.1007/s00787-003-0341-3

Goodman A, Lamping DL, Ploubidis GB (2010) When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ): data from British parents, teachers and children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 38:1179–1191. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x

Elgar FJ, Waschbusch DA, Dadds MR, Sigvaldason N (2007) Development and validation of a short form of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. J Child Fam Stud 16:243–259. doi:10.1007/s10826-006-9082-5

Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS (1983) The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J Marital Fam Ther 9:171–180. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1983.tb01497.x

Wenniger WF, Hageman WJ, Arrindell WA (1993) Cross-national validity of dimensions of family functioning: first experiences with the Dutch version of the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD). Personal Individ Differ 14:769–781. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(93)90090-P

Miller IW, Epstein NB, Bishop DS, Keitner GI (1985) The McMaster family assessment device: reliability and validity. J Marital Fam Ther 11:345–356. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.1985.tb00028.x

Bouwmans C, Schawo S, Jansen D, Vermeulen K, Reijneveld S, Hakkaart-van Roijen L (2012) Handleiding vragenlijst intensieve jeugdzorg: zorggebruik en productieverlies. [Manual questionnaire intensive care for youth: health care utilization and productivity loss]. Erasmus MC, pp 1–36

Hakkaart-Van Roijen L (2007) Handleiding TiC-P (Vragenlijst voor zorggebruik en productieverliezen bij psychische aandoeningen). [Manual TiC-P (Questionnaire for health care utilization and production loss with psychiatric illness)]. pp 1–46

Jansen DE, Vermeulen KM, Schuurman-Luinge AH, Knorth EJ, Buskens E, Reijneveld SA (2013) Cost-effectiveness of multisystemic therapy for adolescents with antisocial behaviour: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 13:369. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-369

Nanninga M, Reijneveld SA, Knorth EJ, Jansen DEMC (2016) Expectations of barriers to psychosocial care: views of parents and adolescents in the community. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 25:107–117. doi:10.1007/s00787-015-0717-1

Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS) (2006) Standard Onderwijsindeling 2006 [Standard Education Classification 2006]. http://www.cbs.nl/nl-NL/menu/methoden/classificaties/overzicht/soi/2006/default.htm. Accessed September 27 2013

Anderson JE, Lowen CA (2010) Connecting youth with health services. Can Fam Physician 56:778–784

Knorth EJ, Knot-Dickscheit J, Strijker J (2009) Intervention und Prävention. In: Andresen S (ed) Handwörterbuch Erziehungswissenschaft. Beltz Verlag, Weinheim/Basel, pp 438–451

Briggs-Gowan MJ, Horwitz SM, Schwab-Stone M, Leventhal JM, Leaf PJ (2000) Mental health in pediatric settings: distribution of disorders and factors related to service use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39:841–849. doi:10.1097/00004583-200007000-00012

Jansen DEMC, Wiegersma P, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, Vollebergh WA, Reijneveld SA (2013) Need for mental health care in adolescents and its determinants: the TRAILS Study. Eur J Public Health 23:236–241. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cks087

Jörg F, Visser E, Ormel J, Reijneveld SA, Hartman CA, Oldehinkel AJ (2016) Mental health care use in adolescents with and without mental disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 25:501–508. doi:10.1007/s00787-015-0754-9

Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J (2010) Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49:980–989. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017

Tick NT, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC (2007) Twenty-year trends in emotional and behavioral problems in Dutch children in a changing society. Acta Psychiatr Scand 116:473–482. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01068.x

Pedrini L, Sisti D, Tiberti A, Preti A, Fabiani M, Ferraresi L, Palazzi S, Parisi R, Ricciutello C, Rocchi MB (2015) Reasons and pathways of first-time consultations at child and adolescent mental health services in Italy: an observational study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Mental Health 9:29. doi:10.1186/s13034-015-0060-9

Metselaar J (2011) Needs-led and family-centred child care and treatment: processes and outcomes. Evaluation of the programme ‘Family Central’. (in Dutch). Dissertation, University of Groningen

Brugman E, Reijneveld SA, Verhulst FC, Verloove-Vanhorick SP (2001) Identification and management of psychosocial problems by preventive child health care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 155:462–469. doi:10.1001/archpedi.155.4.462

Hiebert-Murphy D, Trute B, Wright A (2008) Patterns of entry to community-based services for families with children with developmental disabilities: implications for social work practice. Child Fam Soc Work 13:423–432. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00572.x

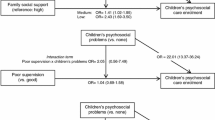

Nanninga M, Jansen DEMC, Knorth EJ, Reijneveld SA (2014) Enrolment of children and adolescents in psychosocial care: more likely in low family social support and poor parenting skills. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24:407–416. doi:10.1007/s00787-014-0590-3

Reijneveld SA, Brugman E, Verhulst FC, Verloove-Vanhorick SP (2004) Identification and management of psychosocial problems among toddlers in Dutch preventive child health care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 158:811–817. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.8.811

Zwaanswijk M, Verhaak PF, Bensing JM, Van der Ende J, Verhulst FC (2003) Help seeking for emotional and behavioural problems in children and adolescents: a review of recent literature. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 12:153–161. doi:10.1007/s00787-003-0322-6

Kleefman M, Reijneveld SA, Jansen DE (2015) Prevalence and determinants of need for formal parenting support among parents raising a child with a borderline to mild intellectual disability. J Intellect Dev Disabil 40:49–56. doi:10.3109/13668250.2014.956659

Shanley DC, Reid GJ, Evans B (2008) How parents seek help for children with mental health problems. Adm Policy Ment Health 35:135–146. doi:10.1007/s10488-006-0107-6

MacGuire J (1999) What works: reducing reoffending. Guideline from research and practice, Chicester

Harder AT, Knorth EJ (2014) Delinquente jeugdigen. [Delinquent juveniles]. In: Grietens H, Vanderfaeillie J, Maes B (eds) Handboek jeugdhulpverlening: een orthopedagogisch perspectief op kinderen en jongeren met problemen [Handbook psychosocial care: an orthopedic perspective on children and adolescents with problems]. Acco, Leuven, pp 299–329

Jörg F, Ormel J, Reijneveld SA, Jansen DE, Verhulst FC, Oldehinkel AJ (2012) Puzzling findings in studying the outcome of “real world” adolescent mental health services: the TRAILS study. PLoS One 7:e44704. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044704

Veerman JW, Ten Brink LT (2001) Antisocial behavior of juveniles: determinants and interventions. In: Van Leeuwen H, Slot W, Uijterwijk M (eds) Lessons learned from follow-up studies (in Dutch). Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers, Lisse, pp 207–224

Knorth EJ, Knot-Dickscheit J, Thoburn J (2015) Supporting children when providing services to families experiencing multiple problems: perspectives and evidence on programmes. Int J Child Fam Welfare 16:2–10

Zwaanswijk M, Verhaak PF, Van der Ende J, Bensing JM, Verhulst FC (2006) Change in children’s emotional and behavioural problems over a 1-year period: associations with parental problem recognition and service use. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 15:127–131. doi:10.1007/s00787-005-0513-4

Bevaart F (2013) Ethnic differences in pathways in care for young children with problem behaviour: road work in progress. Dissertation, Erasmus MC, University Medical Centre Rotterdam

De Wolff MS, Vogels AG, Reijneveld SA (2014) The empirical versus DSM-oriented approach of the Child Behavior Checklist: similarities and dissimilarities. Eur J Psychol Assess 30:22–30

Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS (2007) The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav 31(Supplement 1):S19–S26

Ollendick TH, March JS (2003) Phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: a clinicians guide to effective psychosocial and pharmacological interventions. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Braddick F, Carral V, Jenkins R, Jané-Llopis E (2009) Child and adolescent mental health in Europe: infrastructures, policy and programmes. European Communities, Luxembourg

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by grants from The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw; Grant numbers 15900.0001 and 17372.0001), the Province of Groningen, the University Medical Center Groningen, the University of Groningen, Menzis health insurance company, and the child and adolescent care providers Elker and Accare. The authors wish to thank Roy E. Stewart, PhD, for his assistance in performing the Generalized Linear Mixed Modelling.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nanninga, M., Jansen, D.E.M.C., Knorth, E.J. et al. Enrolment of children in psychosocial care: problems upon entry, care received, and outcomes achieved. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27, 625–635 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1048-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1048-1