Abstract

Background

The effect of coaching on surgical quality and understanding in simulated training remains unknown. The aim of this study was compare the effects of structured coaching and autodidactic training in simulated laparoscopic surgery.

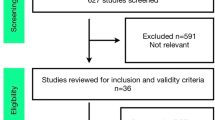

Methods

Seventeen surgically naive medical students were randomized into two groups: eight were placed into an intervention group and received structured coaching, and nine were placed into a control group and received no training. They each performed 10 laparoscopic cholecystectomies on a virtual reality simulator. The surgical quality of the first, fifth, and 10th operations was evaluated by 2 independent blinded assessors using the Competency Assessment Tool (CAT) for cholecystectomy. Understanding of operative strategy was tested before the first, fifth, and 10th operation. Performance metrics, path length, total number of movements, operating time, and error frequency were evaluated. The groups were compared by the Mann–Whitney U test. Proficiency gain curves were plotted using curve fit and CUSUM models; change point analysis was performed by multiple Wilcoxon signed rank analyses.

Results

The intervention group scored significantly higher on the CAT assessment of procedures 1, 5, and 10, with increasing disparity. They also performed better in the knowledge test at procedures 5 and 10, again with an increasing difference. The learning curve for error frequency of the intervention group reached competency after operation 7, whereas the control group did not plateau by procedure 10. The learning curves of both groups for path length and number movements were almost identical; the mean operation time was shorter for the control group.

Conclusions

Clinically relevant markers of proficiency including error reduction, understanding of surgical strategy, and surgical quality are significantly improved with structured coaching. Path length and number of movements representing merely manual skills are developed with task repetition rather than influenced by coaching. Structured coaching may represent a key component in the acquisition of procedural skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Seymour NE, Gallagher AG, Roman SA, O’Brien MK, Bansal VK, Andersen DK, Satava RM (2002) Virtual reality training improves operating room performance: results of a randomized, double-blinded study. Ann Surg 236:458–463

Schijven MP, Jakimowicz JJ, Broeders IA, Tseng LN (2005) The Eindhoven laparoscopic cholecystectomy training course—improving operating room performance using virtual reality training: results from the first EAES accredited virtual reality trainings curriculum. Surg Endosc 19:1220–1226

Palter VN, Orzech N, Reznick RK, Grantcharov TP (2013) Validation of a structured training and assessment curriculum for technical skill acquisition in minimally invasive surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 257:224–230

Grantcharov TP, Kristiansen VB, Bendix J, Bardram L, Rosenberg J, Funch-Jensen P (2004) Randomized clinical trial of virtual reality simulation for laparoscopic skills training. Br J Surg 91:146–150

Dale E (1946) Audiovisual methods in teaching. Dryden Press, New York

Rombeau J, Goldberg A, Lovelend-Jones C (2010) Surgical mentoring: building tomorrow’s leaders. Springer, Verlag

Parsloe E (1999) The manager as coach and mentor. Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, London

Miskovic D, Wyles SM, Ni M, Darzi AW, Hanna GB (2010) Systematic review on mentoring and simulation in laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 252:943–951

Snyder CW, Vandromme MJ, Tyra SL, Hawn MT (2009) Proficiency-based laparoscopic and endoscopic training with virtual reality simulators: a comparison of proctored and independent approaches. J Surg Ed 66:201–207

Pellen M, Horgan L, Roger Barton J, Attwood S (2009) Laparoscopic surgical skills assessment: can simulators replace experts? World J Surg 33:440–447

Vygotsky L (1978) Mind in society: development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Miskovic D, Ni M, Wyles SM, Kennedy RH, Francis NK, Parvaiz A, Cunningham C, Rockall TA, Gudgeon AM, Coleman MG, Hanna GB (2013) Is competency assessment at the specialist level achievable? A study for the national training programme in laparoscopic colorectal surgery in England. Ann Surg 257:476–482

Oldfield RC (1971) The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9:97–113

Brown DC, Miskovic D, Tang B, Hanna GB (2010) Impact of established skills in open surgery on the proficiency gain process for laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc 24:1420–1426

Aggarwal R, Crochet P, Dias A, Misra A, Ziprin P, Darzi A (2009) Development of a virtual reality training curriculum for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 96:1086–1093

Zhang A, Hünerbein M, Dai Y, Schlag PM, Beller S (2008) Construct validity testing of a laparoscopic surgery simulator (Lap Mentor): evaluation of surgical skill with a virtual laparoscopic training simulator. Surg Endosc 22:1440–1444

Miskovic D, Ni M, Wyles SM, Tekkis P, Hanna GB (2012) Learning curve and case selection in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: systematic review and international multicenter analysis of 4852 cases. Dis Colon Rectum 55:1300–1310

Gallagher AG, Ritter EM, Champion H, Higgins G, Fried MP, Moses G, Smith CD, Satava RM (2005) Virtual reality simulation for the operating room: proficiency-based training as a paradigm shift in surgical skills training. Ann Surg 241:364–372

Loukas C, Nikiteas N, Kanakis M, Georgiou E (2011) The contribution of simulation training in enhancing key components of laparoscopic competence. Am Surg 77:708–715

Aggarwal R, Moorthy K, Darzi A (2004) Laparoscopic skills training and assessment. Br J Surg 91:1549–1558

Sturm LP, Windsor JA, Cosman PH, Cregan P, Hewett PJ, Maddern GJ (2008) A systematic review of skills transfer after surgical simulation training. Ann Surg 248:166–179

Disclosures

S. Cole, H. Mackenzie, J. Ha, G. Hanna, and D. Miskovic have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cole, S.J., Mackenzie, H., Ha, J. et al. Randomized controlled trial on the effect of coaching in simulated laparoscopic training. Surg Endosc 28, 979–986 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-3265-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-3265-0