Abstract

Carbonatites host some of the largest and highest grade rare earth element (REE) deposits but the composition and source of their REE-mineralising fluids remains enigmatic. Using C, O and 87Sr/86Sr isotope data together with major and trace element compositions for the REE-rich Kangankunde carbonatite (Malawi), we show that the commonly observed, dark brown, Fe-rich carbonatite that hosts REE minerals in many carbonatites is decoupled from the REE mineral assemblage. REE-rich ferroan dolomite carbonatites, containing 8–15 wt% REE2O3, comprise assemblages of monazite-(Ce), strontianite and baryte forming hexagonal pseudomorphs after probable burbankite. The 87Sr/86Sr values (0.70302–0.70307) affirm a carbonatitic origin for these pseudomorph-forming fluids. Carbon and oxygen isotope ratios of strontianite, representing the REE mineral assemblage, indicate equilibrium between these assemblages and a carbonatite-derived, deuteric fluid between 250 and 400 °C (δ18O + 3 to + 5‰VSMOW and δ13C − 3.5 to − 3.2‰VPDB). In contrast, dolomite in the same samples has similar δ13C values but much higher δ18O, corresponding to increasing degrees of exchange with low-temperature fluids (< 125 °C), causing exsolution of Fe oxides resulting in the dark colour of these rocks. REE-rich quartz rocks, which occur outside of the intrusion, have similar δ18O and 87Sr/86Sr to those of the main complex, indicating both are carbonatite-derived and, locally, REE mineralisation can extend up to 1.5 km away from the intrusion. Early, REE-poor apatite-bearing dolomite carbonatite (beforsite: δ18O + 7.7 to + 10.3‰ and δ13C −5.2 to −6.0‰; 87Sr/86Sr 0.70296–0.70298) is not directly linked with the REE mineralisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbonatites are characteristically enriched in the rare earth elements (REE) and are host to many of the largest REE deposits (Wall 2014; Verplanck et al. 2016). The processes behind the formation of these deposits are increasingly of interest due to the recognition of the REE as a ‘critical metal’ in terms of its supply security (e.g., Chakhmouradian and Wall 2012; European Commission 2014; Chakhmouradian et al. 2015). Only certain carbonatites, however, are REE-rich [e.g., Mountain Pass and Bear Lodge, USA (Castor 2008; Moore et al. 2015; Verplanck et al. 2016); Kangankunde, Tundulu and Songwe, Malawi (Ngwenya 1994; Wall and Mariano 1996; Broom-Fendley et al. 2016a, 2017a, b); Wigu Hill, Tanzania (Mariano 1989); Khibiny, Russia (Zaitsev et al. 1998, 2002, 2015); Barra do Itapirapuã, Brazil (Andrade et al. 1999; Ruberti et al. 2008); and the Mianning-Dechang and Qinling belts in China (Kynicky et al. 2012)]. It is almost always during the last stages of carbonatite emplacement that REE concentrations become high enough to form significant, sometimes rock-forming, quantities of rare earth minerals (e.g., Wall and Zaitsev 2004; Chakhmouradian and Zaitsev 2012). Initial REE mineralisation takes place near the magmatic–hydrothermal interface. Subsequent redistribution and re-working can be associated with silicification, fluorite crystallisation, vug-infilling and other late-stage processes (Wall and Mariano 1996; Doroshkevich et al. 2009).

The earliest REE mineral thought to crystallise in most REE-rich carbonatites is the Na–Ca–REE–Ba–Sr carbonate, burbankite (Wall and Zaitsev 2004). This mineral forms characteristic hexagonal crystals, either co-genetic with calcite in calcite carbonatites (e.g., Bear Lodge and Shaxiongdong; Xu et al. 2008; Moore et al. 2015) or in later REE-rich pegmatites (e.g., Khibiny; Zaitsev et al. 1998). The primary nature of burbankite is supported by its stable (O and C) isotope composition, which is within the range of values for primary magmatic carbonatites (Zaitsev et al. 2002). However, burbankite is not commonly preserved and, in REE-rich carbonatites, the REE are typically hosted in REE–(fluor)carbonates or monazite, commonly in an assemblage with strontianite and baryte. Partial replacement of burbankite by this mineral assemblage has been recognised at a number of localities where the hexagonal pseudo-structure of burbankite is retained (Zaitsev et al. 1998; Moore et al. 2015). REE-bearing hexagonal pseudomorphs at other REE-rich carbonatites are thus thought to have formed through the same process of burbankite replacement (e.g. Kangankunde, Malawi; Wigu Hill, Tanzania; Gem Park, Colorado; Adiounedj, Mali; Wall and Mariano 1996). Subsequent REE mineralisation is likely to be the result of hydrothermal fluids transporting and redistributing the REE. A significant content of carbonate in these fluids is inferred and they are therefore termed (carbo)-hydrothermal (following Zaitsev et al. 1998). Mineralisation in these examples commonly forms in vugs and/or along veins (e.g., Doroshkevich et al. 2009).

Despite the importance of the transition from burbankite to other REE minerals, little is known about the temperature of this mineral replacement, the source of the fluid or how it evolves during REE redistribution. Stable isotopes (C and O) provide a useful tool to assess the above questions. Many of the effects of the principal petrological processes in carbonatites are reasonably well understood (e.g., Deines 1989; Demény et al. 2004). Based on a stable (C and O) isotope study of burbankite replacement at Khibiny (syn. Khibina) and Vuoriyarvi, Zaitsev et al. (2002) suggested burbankite replacement occurred through open-system, post-magmatic isotopic exchange with a low-temperature, water-rich, fluid. REE redistribution occurs in rocks where associated carbonates exhibit a trend toward 18O- and 13C-enrichment (e.g., Andrade et al. 1999; Downes et al. 2014; Trofanenko et al. 2016). In a single bastnäsite-(Ce) analysis from Belaya Zima, this enrichment has also been shown in REE mineralisation (Doroshkevich et al. 2016). Depending on the degree of enrichment of 18O and 13C, this increase has been attributed to Rayleigh fractionation [where δ18O and δ13C have a correlation coefficient of approximately 0.4 (Deines 1970, 1989; Ray and Ramesh 2000)] or through alteration from successive generations of hydrothermal fluid (Santos and Clayton 1995; Ray and Ramesh 1999). In some carbonatites, more abnormal trends have been noted: for example, at the Songwe Hill, Arshan, Fen and Igaliko carbonatites, decreasing δ18O values have been ascribed to either mixing with hot meteoric water, rapid CO2 degassing or crystallisation from a low-δ18O magma (Andersen 1984; Pearce and Leng 1996; Pearce et al. 1997; Doroshkevich et al. 2008; Broom-Fendley et al. 2016b; Doroshkevich et al. 2016).

In this contribution, we present major and trace element data and the results of a multi-isotope study (C, O, 87Sr/86Sr) on the REE-rich Kangankunde carbonatite, Malawi. We aim to understand the relationship between the host carbonatite and the REE mineralisation with respect to the role of deuteric (magma-derived) and meteoric water as well as country rock components. For this, we have analysed strontianite, which occurs as part of the REE pseudomorph assemblage, as a proxy for the process of REE mineralisation as well as more conventional analyses of dolomite and calcite. O isotopes are also presented from quartz mineralisation to elucidate the importance of this late phase of more enigmatic REE mineralisation.

Geological background

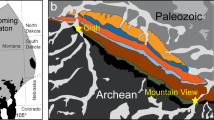

The Kangankunde carbonatite is one of the largest in the Chilwa Alkaline Province (CAP) of Southern Malawi: a 200–300 km area comprising Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous alkaline rocks and carbonatites (Garson 1965; Woolley 1991, 2001). The carbonatite forms a low hill, some 200 m above the surrounding plain, with lower slopes composed of fenitised and, locally, brecciated rocks while the upper slopes are predominantly carbonatite. The earliest intrusion stage at Kangankunde is a small body of apatite–dolomite carbonatite, termed beforsite by Garson and Campbell Smith (1965). This terminology is retained in this manuscript in order to clearly differentiate beforsite from the majority the intrusion, which is formed of arcuate lobes of late-stage, REE-rich, ferroan-dolomite carbonatites, some of which are also Mn-rich (Garson and Campbell Smith 1965; Fig. 1). Clear evidence for the order of intrusion is indicated by local metasomatism of beforsite by REE-bearing fluids and the formation of incipient REE mineralisation in these samples. This consists of increased REE contents in later zones in apatite, and the formation of monazite at corroded apatite crystal margins (Wall and Mariano 1996). The last stage to occur is composed of quartz-rich rocks which predominantly, although not exclusively, occur within the fenite aureole outside of the main intrusion (Fig. 1). This aureole extends up to approximately 2 km from the intrusion and is formed of proximal potassic and distal sodic fenitized Precambrian gneiss (Woolley 1969).

Geological map of Kangankunde showing the approximate sample locations. Samples 1–32 prefixed with BM1993 (P4); 33–133 prefixed with BM1962 (73); 134–306 with SoS-; and 307 with BM1968 (P37). The term ‘agglomerate’ is location-specific and denotes a breccia comprising fragments of country rock and carbonatite in a matrix of carbonatite (see Garson and Campbell Smith 1958). Inset map indicates the position of Kangankunde in southern Malawi.

Much of the carbonatite at Kangankunde contains 5–10 wt% REE, which has stimulated historic mineral exploration (e.g. Holt 1965; Dallas et al. 1987) and the usage of Kangankunde samples for a REE remote-sensing feasibility study (Neave et al. 2016). The most abundant REE mineral is distinctive sector-zoned green monazite-(Ce), which has been well studied with respect to its crystal structure and REE uptake (e.g. Ni et al. 1995; Cressey et al. 1999). Bastnäsite-(Ce) and goyazite–florencite-(Ce) are also important REE minerals at Kangankunde (Wall and Mariano 1996). Rare earth minerals invariably occur in an assemblage with baryte, strontianite and, locally, ferroan dolomite and quartz. These minerals occur as spectacular hexagonal pseudomorphs (Fig. 2), but also in veinlets and drusy cavities (Wall and Mariano 1996).

Radiating monazite–baryte–strontianite pseudomorphs in dolomite carbonatite. a Sample BM 1962, 73 (107), after Wall and Mariano (1996). b Cold-cathodoluminescence image of sample: BM, 1962, 73 (100), courtesy of Tony Mariano

A range of rare earth minerals also occur within the late-stage quartz-rich rocks, including florencite–goyazite and apatite. The latter mineral displays evidence for multiple stages of dissolution–reprecipitation related to late alteration (Wall and Mariano 1996; Broom-Fendley et al. 2016a). The most common REE mineral, however, is monazite occurring in a similar assemblage to that found in the main carbonatite, but without associated strontianite. Wall and Mariano (1996) associate the REE mineralisation in the quartz rocks with the mineralisation in the main carbonatite on the basis of their identical major element composition and REE distribution.

Few isotopic analyses have been carried out on Kangankunde material. 87Sr/86Sr ratios in strontianite and monazite were measured by Hamilton and Deans (1963) and whole-rock 87Sr/86Sr and 144Nd/143Nd ratios were determined in one specimen by Nelson et al. (1988) and Verplanck et al. (2016), and in three specimens by Ziegler (1992). Snelling (1965) dated the intrusion as 123 ± 6 Ma using K–Ar in phlogopite. Wall et al. (1994) calculated a whole-rock Sm–Nd isochron age of 136 ± 11 Ma, and provided an early synopsis of the C and O isotope data presented herein.

Approach and analytical procedures

The specimens used in this study are those of Garson and Campbell Smith (1965) from the collection hosted at the Natural History Museum, London [BM,1962.73 (50–133)], supplemented by samples collected by the authors [BM,1993.P4 (1–32); SoS168–170] and Alan Woolley [BM,1968.P37 (307)]. Descriptions of the samples are outlined in the supplementary information, summarised in Table 1, and their locations are plotted on Fig. 1. Many of the specimens have been previously described by Garson and Campbell Smith (1965), Woolley (1969) and Wall and Mariano (1996). These samples were re-investigated for this study in order to locate fluid inclusions for microthermometry. Unfortunately, inclusions which are clearly petrographically linked to REE mineralisation do not occur at Kangankunde. Some brief notes on the nature of the inclusions are presented in the supplementary information. Rocks are considered REE-rich when REE2O3 concentrations are above 2% and REE-poor when below this value (similar to Jones et al. 2013). Samples were selected to represent the range of different varieties of REE-rich carbonatites and contrasting barren rocks at Kangankunde. They are divided into:

-

1.

Beforsites (apatite–dolomite carbonatites) which are characteristic of early carbonatites and contain lozenge-shaped apatite, phlogopite, REE-bearing perovskite, baddeleyite and olivine

-

2.

REE-poor carbonatites, which comprise:

-

(a)

Light-coloured ankerite/ferroan dolomite carbonatite with little REE mineralisation

-

(b)

Late, Mn-rich, REE-poor carbonatite

-

(c)

Late calcite veins

-

(a)

-

3.

REE-rich carbonatites, including dark Fe- and Mn-rich carbonatite with monazite–strontianite–baryte pseudomorphs (e.g. Figure 2)

-

4.

Monazite-rich quartz rocks from within the main intrusion

-

5.

Quartz rocks from outside of the main intrusion

-

6.

Fenites and country rock gneiss.

Major and trace elements

The samples chosen for whole-rock analysis include apatite-bearing dolomite carbonatite; REE-poor dolomite carbonatites; REE-rich specimens; and coupled REE veins with their host carbonatites. The scarcity of material available precluded analysing some specimens, such as the REE-rich quartz rocks.

Samples were split from the main specimen, keeping the sample size as large as possible, crushed in a jaw crusher and ground using a TEMA mill to < 180 µm. Major and trace elements were determined by ICP-OES (ARL 3410), pyrohydrolysis and CHN analysis at the Natural History Museum, London. For major element determinations, 100 mg samples were fused with 500 mg LiBO2 in Pt–Au crucibles and the resulting glass beads dissolved in dilute HNO3. Some dark residues were dissolved by the addition of 5 ml HCl, before making to 250 ml with water. For the trace elements, including the REE, 1 g samples were treated with 10 ml 50% nitric acid and evaporated to dryness followed by digestion with 30 ml HF plus 5 ml HClO4 until fuming, and then re-dissolved in 25 ml 20% HNO3. A few drops of conc. H2O2 were added to dissolve manganese oxides before diluting to 250 ml with water. During dissolution, a precipitate formed in some samples, identified as barium sulphate by XRD. This would cause underestimation of Ba concentration, but because Sr and REE are minor components in barium sulphate, these are unlikely to be affected. No relation between total concentration and BaO content is present, but high SrO samples correspond to lower totals. This is likely due to the Sr value being in excess of the Sr standard defining the calibration range. Sulphur was determined, along with fluorine, by pyrohydrolysis-ion chromatography. Carbon dioxide and water were determined by combustion analysis using a CHN analyser.

Carbon and oxygen isotopes

Carbon and oxygen isotope ratios were determined in a variety of mineral separates and concentrates. Concentrates were used when insoluble contaminant phases, such as monazite, baryte and quartz, were abundant. In addition, a bulk powder was prepared from three beforsite samples (SoS 168–170) using a handheld drill.

Ankerite/ferroan dolomite was concentrated by magnetic separation. Most of the carbonatites contained ankerite/ferroan dolomite of two or three different magnetic susceptibilities reflecting different Fe contents. The colour of the concentrates was noted during preparation. Strontianite and calcite were concentrated in the non-magnetic residue and separated using methyl iodide (3.31 g cm−3). Quartz separates were made by a combination of magnetic separation and acid dissolution. Baryte and quartz were separated by heavy liquid (bromoform, 2.82 g cm−3). Composite grains and goyazite–florencite contamination was removed by hand-picking, and each sample was checked using SEM–EDS to assess purity.

Most C and O data were acquired at the NERC Isotope Geosciences Laboratory (NIGL). CO2 was extracted offline in vacuo from approximately 10 mg of carbonate by reaction with phosphoric acid at 25.2 °C, essentially following the method of McCrea (1950). The liberated CO2 was cryogenically purified and collected for analysis on a 90 cm sector, triple collector, dual-inlet, mass spectrometer. The data were corrected for instrumental and isobaric effects using the methods of Craig (1957) and the results expressed as δ13C and δ18O‰ relative to VPDB and VSMOW, respectively. Overall analytical reproducibility for δ18O and δ13C was ± 0.1‰ (1σ). In addition, three samples (SoS 168–170) were analysed at the Environment and Sustainability Institute, University of Exeter, using a Sercon 20-22 gas-source mass spectrometer in multiflow configuration. Samples (~ 0.5 mg) were reacted with approximately 100 µl of anhydrous phosphoric acid at 70 °C. Analysis followed routines described by Spötl and Vennemann (2003). Overall analytical reproducibility for δ18O and δ13C was ± 0.03 and 0.19‰ (1σ), respectively.

Quartz samples were analysed at NIGL employing the oxygen liberation technique of Clayton and Mayeda (1963), but utilising ClF3 as a reagent instead of BrF5 (Borthwick and Harmon 1982). Extractions were performed at 526 ± 5 °C. The oxygen yields were converted into CO2 by reaction with a platinised graphite rod heated to 675 °C by an induction furnace. CO2 yields were measured on a capacitance manometer and CO2 isotopic ratios were measured on a CJS Sciences Ltd. Phoenix 390 mass spectrometer (re-built VG 903 automated triple collector machine). The δ18OSMOW results were normalised through the NIGL laboratory quartz standard (LQS: Lochaline Glass Sand) and quoted relative to the international standard quartz NBS 28 (African Glass Sand). Determinations of the LQS standard gave a 1σ reproducibility of 0.16‰, ten replicate analyses of a range of control samples exhibited an average difference of 0.13‰.

87Sr/86Sr isotopes

Strontium isotope analyses were performed at NIGL. Mineral separates, of approximately 150–400 mg, were used for most samples. Whole-rock samples and mineral concentrates were used for samples outside of the main intrusion because these specimens only contain one significant Sr mineral which dominates the isotopic signature. Dissolution techniques varied according to the sample material, H2SO4 was used to dissolve monazite, HCl for apatite and florencite, HF for the fenites and HF followed by HNO3 for quartz–fluorite rocks. After dissolution, the samples were evaporated and converted into chloride by the addition of HCl. Rb and Sr were separated using conventional ion-exchange columns and ratios were determined using TIMS. The 86Sr/88Sr normalisation factor used for Sr was 0.1194 (Nier 1938; Steiger and Jäger 1977). Over the period of data acquisition, 89 analyses of NIST SRM 987 gave an average value of 0.710194, with 2 standard errors of the mean of 0.000004 and 2 standard deviations of 0.000037. Owing to low Rb concentrations, relative to Sr, in the carbonatites, radiogenic ingrowth is negligible and, thus, 87Sr/86Sr is representative of initial values. Only samples from fenite contain sufficient Rb such that the 87Sr/86Sr needs to be corrected.

Results

Major and trace elements

Major and trace element data are presented in Supplementary Table 2 which includes a single analysis from Verplanck et al. (2016). Using the revised carbonatite classification diagram of Gittins and Harmer (1997), most samples plot in the magnesiocarbonatite field, close to the line defining the trend from dolomite to ankerite (Fig. 3). Some samples are more magnesium rich, due to higher modal abundances of phlogopite, while slightly Ca-rich samples have higher apatite concentrations. Two samples plot in the calciocarbonatite field but these are dolomite carbonatites which contain secondary calcite. There is no apparent relationship between the degree of Fe enrichment and the REE2O3 content. The highest ratios of Fe + Mn to Mn + Ca occur in the beforsites and REE-poor rocks (Fig. 4a).

The REE contents of the carbonatites range from 0.25 wt% REE2O3 in beforsite up to 8–15 wt% in the REE-rich carbonatites. There is a clear division between the REE-rich samples and the other rocks, including rocks very closely related to REE-rich carbonatites [e.g. BM 1993, P4 (5)]. This is especially illustrated by the difference between the REE contents of the mineralised veins and the less-mineralised host carbonatites. Two of the beforsites [BM 1962, 72 (50) and (58)] have the lowest REE concentration but a third [BM 1962, 72 (59)] is slightly more REE-enriched owing to incipient REE mineralisation (Wall and Mariano 1996). Higher REE2O3 contents correspond to elevated Sr and Ba concentrations (Fig. 4b, c). This reflects the association between monazite, strontianite and baryte in the REE mineral assemblage. Niobium also is associated with increasing REE contents and, in the REE-rich rocks, Nb is hosted in accessory amounts of Sr-bearing pyrochlore (Fig. 4d). This is somewhat unusual because pyrochlore, the principal host for Nb in carbonatites, generally occurs in calcite carbonatites (Chakhmouradian 2006). There is little relationship between the REE and F at Kangankunde (Fig. 4e). This reflects the low abundance of REE–fluorcarbonates relative to monazite-(Ce). Higher F contents occur in the phlogopite- and apatite-rich beforsite samples.

All of the Kangankunde rocks are highly enriched in the light (L)REE (Fig. 5). Beforsite samples have the flattest REE patterns, except for the sample with incipient REE mineralisation which has slightly elevated LREE contents [BM 1962, 72 (59); Wall and Mariano (1996)]. REE-rich samples have the steepest REE distributions, except where the host carbonate has been separated from REE veins. These plot in a similar range to the REE-poor carbonatites. All of the analysed samples display a prominent negative Y anomaly, which is most pronounced in the more LREE-rich samples.

Carbon and oxygen in carbonates

C and O isotope data from carbonates are considered relative to the Primary Igneous Carbonatite (PIC) box. This box represents the compositional range of globally distributed carbonatites, unaffected by surficial processes, and is considered representative of the mantle source composition (Taylor et al. 1967; Deines 1989; Keller and Hoefs 1995; Demény et al. 2004; Jones et al. 2013). In this contribution we use the PIC field of Demény et al. (2004). Overall, there is a wide range of δ13C and δ18O values in the carbonate minerals at Kangankunde (Table 1). However, the different carbonate minerals plot into distinct groups, summarised in the following four paragraphs.

Only analyses of ferroan dolomite from the beforsite (apatite–dolomite carbonatite) plot in the PIC box (Fig. 6a). A beforsite containing incipient REE mineralisation (BM 1962, 73 (59) [Wall and Mariano, 1996]) has higher δ13C values, similar in composition to light-coloured carbonates from the mineralised samples, and plots outside of the PIC box.

Oxygen and carbon isotope ratios from Kangankunde carbonates. PIC = primary igneous carbonatite box from Demény et al. (2004). All data-points represent REE-rich carbonatites with the exception of dashed circles (beforsite) and dotted data-points (REE-poor carbonatites). a Strontianite (diamonds) plots in a distinctive group and the equivalent dolomite compositions for a range of temperatures are indicated for comparison. Ferroan dolomite (circles) span a range of δ18O values, corresponding to the darkness of the mineral grain analysed, as represented by the infill colour. No colour data are available for dolomite represented by dashed circles (beforsite). Calcite (squares) broadly follows the dolomite trend, but distinctly late supergene calcite is progressively 13C-depleted. b The same data compared with model carbonate compositions forming from a CO2-rich fluid, representative of a degassing PIC source at a range of temperatures. c Same as b, but with modelled carbonate compositions from a H2O rich fluid, at different degrees of alteration and temperature. Path (1) represents complete replacement at 100 °C, while (2) and (3) represent 50 and 10% replacement at 100 °C, respectively

Ferroan dolomite/ankerite from the REE-rich carbonatites spans a wide range of δ18O values, extending from approximately + 6 to + 24‰. The corresponding δ13C ranges, however, are more restricted, ranging from − 5 to − 1‰, outside of the PIC box (Fig. 6a). Oxygen and, to a lesser extent, carbon isotope ratios in the ferroan dolomite/ankerite vary in relation to the ‘darkness’ of the carbonate analysed. While this observation is qualitative, it appears that the darker the carbonate, the more positive the δ18O value (Fig. 6).

In contrast to the ferroan dolomite, strontianite from all rocks plots in a tight cluster of + 3 to + 5‰ δ18O and − 3.5 to − 3.2‰ δ13C. While relatively close to the values for the light-coloured ferroan dolomite samples (0.6–2.8‰ lower in δ18O), these two phases are unlikely to have crystallised in equilibrium: this is supported by the pseudomorph textures, which indicate later crystallisation of strontianite through replacement of a hexagonal phase (e.g. Fig. 2), and through comparison with C and O fractionation factors between dolomite and strontianite at different temperatures. For example, using the O-isotope fractionation factors of Horita (2014) (80–350 °C) and Chacko and Deines (2008) (350–500 + °C), these two minerals should be in equilibrium between approximately 250 and 400 °C. However, using the C-isotope fractionation factors of Deines (2004), these two phases cannot be in equilibrium as fractionation between dolomite and strontianite should result in strontianite having more positive δ13C values. Nevertheless, it is possible that, across the suggested temperature range, the strontianite is in equilibrium with carbonate of a composition equivalent to the top left corner of the PIC box (Fig. 6a).

Data from calcite broadly follow the same trend as the dolomite, but a calcite vein from a joint plane [BM, 1993, P4 (18)], has high δ18O and relatively low δ13C values, suggesting a low temperature of formation and the incorporation of some organic-derived C. This calcite is, therefore, thought to be deposited from surface-derived waters, probably significantly later than the other carbonates at Kangankunde. Calcite separated from within one rock [BM, 1993, P4 (9)] plots in the same field and is thought to be of the same origin. There is no evidence for primary calcite at Kangankunde.

Oxygen in quartz

Oxygen isotope values in quartz range from + 8.3 to + 17.7‰ (δ18O vs SMOW; Table 1). However, the lowest values are restricted to low-grade fenite samples, and most mineralised specimens plot between + 12.5 and + 17.7‰. In sample BM, 1962, 73 (100), where data are available for quartz (+ 13.2‰ δ18O) and carbonates (+ 6.7 to + 9.3‰ δ18O), these minerals are unlikely to be in equilibrium. Comparison between dolomite–H2O (Horita 2014) and quartz–H2O (Matsuhisa et al. 1979; Zhang et al. 1989) fractionation factors, at temperatures of 250–400 °C, indicates that Δ18ODol-Qrtz should not exceed 1.1‰: far lower than the observed difference.

87Sr/86Sr isotopes

87Sr/86Sr isotope ratios for almost all samples in this study lay in a narrow band between 0.70302 and 0.70307 (n = 20), similar to the range of results of Ziegler (1992), affirming a common carbonatite-derived origin for all samples (Table 1; Fig. 7). The beforsite samples all have slightly lower ratios, falling within a narrow envelope of 0.70296–0.70298 (n = 4). Other exceptions include fenite samples and the quartz–fluorite and quartz–florencite rocks. Low-grade quartz fenite has an initial ratio (see Table 1 for Rb concentrations and corrections) of 0.70464, while a fenite vein within the same rock has a ratio of 0.70328. The quartz–fluorite and quartz–florencite rocks are the furthest two samples outside of the main carbonatite. These specimens have elevated 87Sr/86Sr ratios, suggesting some isotopic mixing with a country rock source. Excluding two data-points from calcite, there is a correlation between δ13C and 87Sr/86Sr (R 2 = 0.5794). However, this correlation is predominantly controlled by low 87Sr/86Sr ratio of two beforsite data-points and, therefore, is probably not significant. There appears to be little relation between 87Sr/86Sr and δ18O values.

87Sr/86Sr ratios of minerals from different rock types at Kangankunde. Note the similar beforsite values, which are markedly lower than the other carbonatite analyses at Kangankunde. Many quartz rocks have the same 87Sr/86Sr ratios as carbonatites, with the exception of whole-rock samples and fluorite concentrate, which occur outside of the main intrusion and are likely contaminated with fenite/country rock. Ap apatite, f fluorite

Discussion

Relationship between beforsite and the mineralised carbonatites

The earliest carbonatite at Kangankunde is beforsite (apatite–dolomite carbonatite), which forms a small central plug (Fig. 1). Based on the abundance of phlogopite in this rock, Garson and Campbell Smith (1965) suggested that it is a ‘carbonatised nephelinite’ where the carbonate is an alteration product related to later REE-bearing carbonatites. However, the new C and O isotope data plot within the PIC field and indicate that this rock type is a primary magmatic carbonatite. This interpretation is supported by the presence of ovoid apatite grains, which are commonly an early liquidus phase in carbonatites (Le Bas 1989), as well as evidence of REE-rich fluids reacting with apatite and forming incipient REE mineralisation (Wall and Mariano 1996).

Beforsite is unlikely to have any parental relationship to the REE-mineralised carbonatites at Kangankunde. It is mineralogically distinct, with much ovoid apatite, altered olivine and accessory baddeleyite and perovskite (Garson and Campbell Smith 1965; Wall and Mariano 1996). Its 87Sr/86Sr ratios also form a separate population (Fig. 7). There is no clear compositional relationship between beforsite and REE-rich carbonatite, and beforsite has distinctly lower C isotope ratios while retaining similar O isotope values. It is, therefore, difficult to envisage any fractionation or hydrothermal process which relates these rock types as both would increase the O and C isotope ratios (e.g. Deines 1970, 1989; Santos and Clayton 1995; Ray and Ramesh 1999, 2000; Trofanenko et al. 2016). This interpretation is supported by the size of the two carbonatite bodies exposed; the earlier apatite-bearing dolomite carbonatite being much smaller than the later REE-rich carbonatites (Fig. 1).

Order of events and number of fluid generations

The exact number of generations of fluid involved in the mineralising process at Kangankunde, is somewhat equivocal. This is a common problem in REE-mineralised carbonatites, as they are highly susceptible to auto-metasomatism, dissolution, and alteration by groundwater. However, combining the field and mineralogical evidence outlined in previous contributions (e.g. Garson and Campbell Smith 1965; Wall and Mariano 1996; Duraswami and Shaikh 2014; Broom-Fendley et al. 2016a) with the new isotope data presented herein, it is possible to outline the order of events and postulate two major fluid generations. These different fluid generations are divided into (1) mineralising fluids, responsible for altering burbankite to the strontianite–baryte–monazite mineral assemblage; and (2) subsequent altering fluids, which modify the isotopic composition of the host carbonates and can erroneously be associated with the mineralising event. These are discussed in the following sub-sections. This separation of fluids is arbitrary and is intended to represent processes at different stages of the evolution of the deposit, rather than separate fluids from different sources.

Source of REE mineralising fluid(s) and nature of the mineralisation

The negative Y anomaly in all of the REE-rich samples is compelling evidence for interaction between the REE and a hydrothermal fluid (c.f. Bau 1996). The nature of the ligands involved in this fluid, however, is less clear and there is little direct evidence to help with this. In fluids capable of transporting the REE, fluoride complexation has been shown to preferentially transport Y over the HREE (Bau and Dulski 1995; Loges et al. 2013), and Bühn (2008) suggested that the negative Y anomaly in carbonatites was evidence for fluid transport of Y and the HREE away from carbonatites. However, the F-poor nature of most of the samples at Kangankunde suggests a diminished role for REE–fluoride complexes. Furthermore, carbonate complexes are unlikely because they would cause Y to behave more like the LREE and thus should create a positive Y anomaly (Bau and Dulski 1995). Chloride is currently commonly favoured as the most important ligand for transporting the REE (e.g. Williams-Jones et al. 2012; Downes et al. 2014; Trofanenko et al. 2016; Broom-Fendley et al. 2016a, 2017a) but there is not yet any fluid inclusion evidence at Kangankunde to support this. Given the circumstantial nature of the evidence for different fluid compositions, it is difficult to conclude how the REE are transported at Kangankunde. However, the low F contents from the whole-rock data, in combination with the results of recent experimental work, summarised above, strongly suggest that F has a diminished role for REE complexation and deposition.

There is little evidence for any contribution from external fluids for the REE mineralisation process. 87Sr/86Sr values are consistent in the REE-rich carbonatites (Fig. 7), although this is, in part, an effect of their very high Sr contents making 87Sr/86Sr an insensitive parameter. The tight clustering of strontianite δ18O and δ13C values, representing the REE mineral assemblage, can be achieved through two mechanisms: (1) equilibrium fractionation between strontianite and dolomite in a carbonatite-derived fluid/melt or (2) equilibrium degassing from a PIC source. Equilibrium fractionation, at a range of temperatures, between strontianite and a PIC fluid is outlined in Fig. 6a. This demonstrates that strontianite is in equilibrium with primary igneous carbonatite at a temperature range of approximately 350 °C or less (Fig. 6a; Chacko and Deines 2008; Horita 2014). The role of degassing can be evaluated using a model whereby changes in C and O isotope ratios between carbonate (taking calcite as a proxy for dolomite), H2O, and CO2 are defined as a function of two mass-balance equations (Santos and Clayton 1995; Ray and Ramesh 1999):

and

where F C = moles of carbon in the fluid, R C = moles of carbon in the rock, ∆ Crock–fluid = difference in carbon isotopes between the rock and the fluid, r = molar ratio of CO2 to H2O in the fluid (here considered as 1000, to reflect a CO2-rich fluid), and:

where \(\upalpha^{18} {\text{O}}_{{{\text{cc}}{-}{\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) and \(\upalpha^{18} {\text{O}}_{{{\text{H}}_{2} {\text{O}} - {\text{CO}}_{2} }}\) are fractionation factors between calcite–CO2 and H2O–CO2, at a given temperature. Calcite is assumed to represent carbonatite and fractionation factors for calcite–CO2 are taken from Chacko et al. (1991), while H2O–CO2 is taken from Richet et al. (1977). Initial δ18O and δ13C values used are + 4.5‰ and − 3.5‰, similar to those of strontianite. Model calculations are included in the supplementary material.

The modelled effects of different degrees of degassing are presented in Fig. 6b. In these models, the degree of exchange between the CO2-rich fluid and the rock (F C/R C) is related to temperature: as temperature decreases the degree of exchange increases. The modelled temperature range is between 350 and 100 °C, and the corresponding F C/R C ranges are from (1) 0–1, representing complete exchange, (2) 0–0.5, and (3) 0–0.1, representing partial exchange between the fluid and the crystallising carbonate (Fig. 6b).

As can be seen in Fig. 6b, degassing represents an equally viable mechanism (to fractionation) for obtaining the elevated strontianite δ13C and decreased δ18O ratios relative to a hypothetical PIC source. This similarity is because, in terms of their effect on the carbonate stable isotope composition, both mechanisms are variations on carbonate–CO2 fractionation. The process of degassing, however, typically results in brecciation of the host rock. While breccia pipes and degassing structures are apparent in many carbonatites (e.g. Songwe Hill and Chilwa Island, Malawi; Broom-Fendley et al. 2017b, Garson and Campbell Smith 1958), they are not widespread at Kangankunde. Thus, fractionation between strontianite and a PIC fluid (Fig. 6a) is favoured over degassing as the isotopic source of the REE mineralising fluids.

Unfortunately, there is no burbankite at Kangankunde with which to compare the strontianite values, so it is difficult to infer compositional changes during pseudomorph formation. Strontianite C and O isotope compositions are lower than those from burbankite at other localities (e.g. δ18O, + 7.3 to + 7.6‰, Khibiny; + 8.1‰, Vuoriyarvi; + 9.7‰, Bear Lodge; Zaitsev et al. 2002; Moore et al. 2015), but these are all close to, or within, the PIC box.

The similar composition of strontianite to primary magmatic carbonatites indicates that alteration and breakdown of burbankite to the monazite-bearing pseudomorph assemblage is likely to have occurred soon after its formation. It is, therefore, suggested that burbankite crystallisation and breakdown occurs over a narrow temperature window. Interaction with a cooling deuteric fluid is the most likely cause of this breakdown, imparting a negative Y anomaly. However, the REE would rapidly reprecipitate owing to the low solubility of monazite-(Ce) (Poitrasson et al. 2004; Cetiner et al. 2005; Louvel et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2016). The C and O data for strontianite, in equilibrium with the monazite-(Ce), indicate that no meteoric water input is required for this process.

The formation of burbankite probably occurred in a transition environment, from magmatic to (carbo)-hydrothermal fluids, as indicated by the pegmatitic nature of the pseudomorphs (Wall 2000; Wall et al. 2001) and unlikely to be related to late-stage hydrothermal fluid activity as proposed at other complexes by Zaitsev et al. (2002). The strontianite stable isotope data presented here contrast with analyses of the pseudomorph assemblage from Khibiny and Vuoriyarvi which have much more 18O-enriched compositions, up to 18‰ (Zaitsev et al. 2002). A possible reason for this is discussed below.

Alteration after the formation of the main mineral assemblage

The dominant trend in the C and O data, towards higher δ18O values (Fig. 6a), is probably the result of increasing degrees of exchange between dolomite and later, cooling, deuteric fluid(s) (e.g. Demény et al. 2004). The role of this alteration can be evaluated using the models outlined in Eqs. 1–3, changing r to 0.001 to reflect a low CO2 fluid (see supplementary information and Fig. 6c). In these models, the effect of differing degrees of exchange (equivalent to degree of alteration) is also related to temperature: as temperature decreases the degree of alteration increases. Increasing the degree of exhange while lowering fluid temperature is justified as carbonate solubility increases as temperature decreases (Dolejš and Manning 2010). Support is also lent through the increasing ‘darkness’ of the dolomite samples as δ18O increases. This colour change is likely to be due to the breakdown of ferroan dolomite, which is less stable than its magnesian counterpart (Chai and Navrotsky 1996), into iron oxides and dolomite or, occasionally, calcite. Isotopic exchange with water causes in-situ alteration of the ferroan dolomite resulting in Fe-oxide exsolution and thus a darker mineral grain. Textural evidence at Kangankunde, such as etching along cleavage and spongey, pitted surfaces on the dolomite, supports this interpretation (Duraswami and Shaikh 2014). The dolomite data broadly match the trend of the models, with the darkest samples generally having higher δ18O values (Fig. 6c). Combined, the models and data indicate that carbonate dissolution and isotopic exchange, as temperature decreases, are likely to be the main controls on the dolomite composition. Calcite compositions, with the exception of those from supergene veins, broadly follow the main dolomite trend, indicating that it is affected by a similar process. Strontianite does not appear to be affected by late re-equilibration, suggesting that it is less susceptible to isotopic exchange than dolomite or calcite. The reason for this is unknown, and beyond the scope of this manuscript.

The above processes illustrate the cooling of a single fluid but this does not preclude the possibility that multiple phases of re-circulating fluid are present at Kangankunde. Multiple fluid generations, if they are of the same composition, would likely have the same effect on the dolomite C and O isotope values as a single cooling fluid. The modelled processes could explain the difference between the stable isotope composition of the pseudomorph assemblage at Khibiny and Vuoriyarvi and the strontianite at Kangankunde. The analyses of this assemblage at Khibiny and Vuoriyarvi included calcite, which may have been susceptible to subsequent isotopic exchange. Furthermore, the above process does not eliminate the possibility that the REE were re-distributed by these cooling, altering fluids. Such a process is indeed likely at many carbonatites and is supported by the presence of REE minerals in veins and vugs (e.g. Doroshkevich et al. 2009; Downes et al. 2014; Broom-Fendley et al. 2016b). However, the model results and dolomite data illustrate the difficulty in unequivocally tying carbonate isotopic compositions with REE mineralisation. To obtain representative stable isotope data linked to the mineralisation process, it may be better to analyse the REE-bearing mineral (e.g. Broom-Fendley et al. 2016b).

Interaction between the carbonatite and surrounding country rock

Both within and around Kangankunde, unusually quartz-rich rocks occur which are commonly REE-mineralised (Garson and Campbell Smith 1965; Wall 2000; Broom-Fendley et al. 2016a). These are found up to 1.6 km away from the main intrusion (Fig. 1). The consistent 87Sr/86Sr ratios (within uncertainty) indicate that, with the exception of the quartz–fluorite and quartz–florencite rocks [BM 1962, 73 (128) and (133)], the quartz rocks are likely to be derived from the carbonatite (Fig. 8). The two excluded samples, with higher 87Sr/86Sr ratios, are likely to be contaminated with a small amount of country rock. The sample scarcity of the quartz rocks means no whole-rock data are available to model mixing between the carbonatite and country rock end-members. However, fenite samples are broadly representative of the country rock and these have a significantly more radiogenic 87Sr/86Sr ratio than the carbonatite (Table 1).

Quartz oxygen isotope values (triangles) and 87Sr/86Sr ratios (circles) in quartz rocks from within and outside of the main intrusion. Oxygen isotope values increase with greater distance from the main intrusion, excluding rocks which have incorporated a country rock component based on elevated 87Sr (greyed out: 128, 133). Three-digit labels reflect BM sample numbers. Distances are approximate. Analytical uncertainty is included next to the axes

Rare earth mineralisation in the quartz-rich rocks suggests carbonatite-derived fluids have the capability to transport the REE well outside of the main intrusion and into the fenite aureole. A comparison of the distance of these rocks from the main carbonatite centre (taken as the middle of the REE-rich carbonatite) with their quartz O isotope composition illustrates that more distal samples have higher δ18O values than their closer counterparts (Fig. 8). Deines (1970) noted a similar trend in non-REE-mineralised calcite in ijolite at the Oka complex, Canada, where the 18O content increased away from the carbonatite contact. The simplest interpretation of these examples is that they are caused by quartz (or calcite) crystallising at lower temperatures away from the main carbonatite intrusion. However, petrographic studies of the Kangankunde rocks indicate that quartz formed after the REE mineralisation (Wall and Mariano 1996; Broom-Fendley et al. 2016a), and so its composition does not provide information about the conditions of REE transportation. A role of meteoric water in these more distal samples cannot, therefore, be excluded.

Conclusions

The main conclusions from this work are as follows:

-

1.

Strontianite is in isotopic equilibrium (δ18O and δ13C) with a hypothetical PIC-derived fluid, suggesting that the monazite-(Ce), strontianite, baryte pseudomorph assemblage formed soon after the probable original burbankite crystals. Given the similar ranges of δ18O and δ13C values with PIC, and consistent 87Sr/86Sr values for all the REE-rich carbonatites, no significant input of meteoric water was required for this process, which is the result of deuteric (carbo)-hydrothermal fluid.

-

2.

Dolomite and calcite, in the REE-rich samples, have high δ18O values relative to strontianite and the PIC field. Modelled fluid compositions suggest these values are caused by increasing degrees of alteration by low-temperature fluids. Such models are corroborated by the increasing ‘darkness’ of dolomite caused by Fe exsolution at lower temperatures. This process for formation of dark ‘oxidised’ carbonates is separate from the REE mineralisation. Use of δ18O and δ13C isotopes of calcite and dolomite in REE-rich rocks to infer fluid sources and temperatures may yield misleading results.

-

3.

REE mineralisation in quartz rocks occurs up to 1.5 km outside of the main carbonatite and has similar δ18O and 87Sr/86Sr values to the REE-rich carbonatites. This similarity suggests carbonatite-derived fluids have the capability to transport the REE well outside of the main intrusion and into the fenite aureole.

-

4.

There are two main varieties of carbonatite present at Kangankunde: small intrusions of earlier apatite-bearing dolomite carbonatite (beforsite) and later REE-rich ferroan dolomite carbonatites. These have different 87Sr/86Sr and C isotope ratios and cannot readily be linked by a common genetic process. The earlier dolomite plots into the PIC field, and is not a product of alteration of a silicate intrusion as previously proposed.

With these conclusions, we are able to deduce that the source for REE-bearing fluids is predominantly carbonatite-derived and that the majority of mineralisation occurs over a narrow temperature window. This is likely to be between 250 and 400 °C, based on equilibrium fractionation between strontianite and a hypothetical magmatic carbonatite. The fluid composition, in terms of what is complexing and transporting the REE, remains enigmatic, but we infer a weak role for fluorine.

References

Andersen T (1984) Secondary processes in carbonatites: petrology of ‘Rødberg’ (hematite-calcite-dolomite carbonatite) in the Fen central complex, Telemark (South Norway). Lithos 17:227–245

Andrade F, Möller P, Lüders V, Dulski P, Gilg H (1999) Hydrothermal rare earth elements mineralization in the Barra do Itapirapuã carbonatite, southern Brazil: behaviour of selected trace elements and stable isotopes (C, O). Chem Geol 155:91–113

Bau M (1996) Controls on the fractionation of isovalent trace elements in magmatic and aqueous systems: evidence from Y/Ho, Zr/Hf, and lanthanide tetrad effect. Contrib Mineral Petrol 123:323–333

Bau M, Dulski P (1995) Comparative study of yttrium and rare-earth element behaviours in fluorine-rich hydrothermal fluids. Contrib Mineral Petrol 119:213–223

Borthwick J, Harmon RS (1982) A note regarding ClF3 as an alternative to Br F3 for oxygen isotope analysis. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 46:1665–1668

Broom-Fendley S, Styles MT, Appleton JD, Gunn G, Wall F (2016a) Evidence for dissolution-reprecipitation of apatite and preferential LREE mobility in carbonatite-derived late-stage hydrothermal processes. Am Mineral 101:596–611

Broom-Fendley S, Heaton T, Wall F, Gunn G (2016b) Tracing the fluid source of heavy REE mineralisation in carbonatites using a novel method of oxygen-isotope analysis in apatite: the example of Songwe Hill, Malawi. Chem Geol 440:275–287

Broom-Fendley S, Brady AE, Wall F, Gunn G, Dawes W (2017a) REE minerals at the Songwe Hill carbonatite, Malawi: HREE-enrichment in late-stage apatite. Ore Geol Rev 81:23–41

Broom-Fendley S, Brady AE, Horstwood MSA, Woolley AR, Mtega J, Wall F, Dawes W, Gunn G (2017b) Geology, geochemistry and geochronology of the Songwe Hill carbonatite, Malawi. J Afr Earth Sci 134:10–23

Bühn B (2008) The role of the volatile phase for REE and Y fractionation in low-silica carbonate magmas: implications from natural carbonatites, Namibia. Mineral Petrol 92:453–470

Castor S (2008) The Mountain Pass rare-earth carbonatite and associated ultrapotassic rocks, California. Can Mineral 46:779–806

Cetiner ZS, Wood SA, Gammons CH (2005) The aqueous geochemistry of the rare earth elements. Part XIV. The solubility of rare earth element phosphates from 23 to 150 °C. Chem Geol 217:147–169

Chacko T, Deines P (2008) Theoretical calculation of oxygen isotope fractionation factors in carbonate systems. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 72:3642–3660

Chacko T, Mayeda TK, Clayton RN, Goldsmith JR (1991) Oxygen and carbon isotope fractionations between CO2 and calcite. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 55:2867–2882

Chai L, Navrotsky A (1996) Synthesis, characterization, and energetics of solid solution along the dolomite-ankerite join, and implications for the stability of ordered CaFe(CO3)2. Am Mineral 81:1141–1147

Chakhmouradian AR (2006) High-field-strength elements in carbonatitic rocks: geochemistry, crystal chemistry and significance for constraining the sources of carbonatites. Chem Geol 235:138–160

Chakhmouradian AR, Wall F (2012) Rare earth elements: minerals, mines, magnets (and more). Elements 8:333–340

Chakhmouradian AR, Zaitsev AN (2012) Rare earth mineralization in igneous rocks: sources and processes. Elements 8:347–353

Chakhmouradian AR, Smith MP, Kynicky J (2015) From “strategic” tungsten to “green” neodymium: a century of critical metals at a glance. Ore Geol Rev 64:455–458

Clayton RN, Mayeda TK (1963) The use of bromine pentafluoride in the extraction of oxygen from oxides and silicates for isotopic analysis. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 27:43–52

Craig H (1957) Isotopic standards for carbon and oxygen and correction factors for mass-spectrometric analysis of carbon dioxide. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 12:133–149

Cressey G, Wall F, Cressey BA (1999) Differential REE uptake by sector growth of monazite. Mineral Mag 63:813–828

Dallas S, Laval M, Malunga GWP (1987) Evaluation of known mineral deposits. Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières, Orleans (unpublished)

Deines P (1970) The carbon and oxygen isotopic composition of carbonates from the Oka carbonatite complex, Quebec, Canada. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 34:1199–1225

Deines P (1989) Stable isotope variations in carbonatite. In: Bell K (ed) Carbonatites: genesis and evolution. Unwin Hyman, London, pp 301–359

Deines P (2004) Carbon isotope effects in carbonate systems. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 68:2659–2679

Demény A, Sitnikova M, Karchevsky P (2004) Stable C and O isotope compositions of carbonatite complexes of the Kola Alkaline Province: phoscorite–carbonatite relationships and source compositions. In: Wall F, Zaitsev AN (eds) Phoscorites and carbonatites from mantle to mine: the key example of the Kola Alkaline Province. The Mineralogical Society, London, pp 407–431

Dolejš D, Manning CE (2010) Thermodynamic model for mineral solubility in aqueous fluids: theory, calibration and application to model fluid-flow systems. Geofluids 10:20–40

Doroshkevich AG, Ripp GS, Viladkar SG, Vladykin NV (2008) The Arshan REE carbonatites, southwestern Transbaikalia, Russia: mineralogy, paragenesis and evolution. Can Mineral 46:807–823

Doroshkevich AG, Viladkar SG, Ripp GS, Burtseva MV (2009) Hydrothermal REE mineralization in the Amba Dongar carbonatite complex, Gujarat, India. Can Mineral 47:1105–1116

Doroshkevich AG, Veksler IV, Izbrodin IA, Ripp GS, Khromova EA, Posokhov AV, Travin AV, Vladykin NV (2016) Stable isotope composition of minerals in the Belaya Zima plutonic complex, Russia: implications for the sources of the parental magma and metasomatizing fluids. J Asian Earth Sci 116:81–96

Downes PJ, Demény A, Czuppon G, Lynton Jaques A, Verrall M, Sweetapple M, Adams D, McNaughton NJ, Gwalani LG, Griffin BJ (2014) Stable H–C–O isotope and trace element geochemistry of the Cummins Range Carbonatite Complex, Kimberley region, Western Australia: implications for hydrothermal REE mineralization, carbonatite evolution and mantle source regions. Miner Deposita 49:905–932

Duraswami RA, Shaikh TN (2014) Fluid-rock interaction in the Kangankunde Carbonatite Complex, Malawi: SEM based evidence for late stage pervasive hydrothermal mineralisation. Cent Eur J Geosci 6:476–491

European Commission (2014) Report on critical raw materials for the EU, report of the ad hoc working group on defining critical raw materials. http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/10010/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6cJu6Nnpj)

Garson MS (1965) Carbonatites in southern Malawi. Blletin, Geological Survey, Malawi, no 15

Garson MS, Campbell Smith W (1958) Chilwa Island. Memoir. Geological Survey, Malawi 1

Garson MS, Campbell Smith W (1965) Carbonatite and agglomeratic vents in the western Shire Valley. Memoir. Geological Survey, Malawi 3

Gittins J, Harmer R (1997) What is ferrocarbonatite? A revised classification. J Afr Earth Sci 25:159–168

Hamilton EI, Deans T (1963) Isotopic composition of strontium in some African carbonatites and limestones and in strontium minerals. Nature 198:776–777

Holt DN (1965) The Kangankunde Hill rare earth prospect. Bulletin, Geological Survey, Malawi, no 20

Horita J (2014) Oxygen and carbon isotope fractionation in the system dolomite–water–CO2 to elevated temperatures. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 129:111–124

Jones AP, Genge M, Carmody L (2013) Carbonate melts and carbonatites. Rev Mineral Geochem 75:289–322

Keller J, Hoefs J (1995) Stable isotope characteristics of recent natrocarbonatites from Oldoinyo Lengai. In: Bell K, Keller J (eds) Carbonatite volcanism. Springer, London, pp 113–123

Kynicky J, Smith MP, Xu C (2012) Diversity of rare earth deposits: the key example of China. Elements 8:361–367

Le Bas M (1989) Diversification of carbonatite. In: Bell K (ed) Carbonatites: genesis and evolution. Unwin Hyman, London, pp 428–447

Loges A, Migdisov AA, Wagner T, Williams-Jones AE, Markl G (2013) An experimental study of the aqueous solubility and speciation of Y (III) fluoride at temperatures up to 250 °C. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 123:403–415

Louvel M, Bordage A, Testemale D, Zhou L, Mavrogenes J (2015) Hydrothermal controls on the genesis of REE deposits: insights from an in situ XAS study of Yb solubility and speciation in high temperature fluids (T < 400 °C). Chem Geol 417:228–237

Mariano AN (1989) Economic geology of rare earth minerals. Rev Mineral 21:309–334

Matsuhisa Y, Goldsmith JR, Clayton RN (1979) Oxygen isotopic fractionation in the system quartz–albite–anorthite–water. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 43:1131–1140

McCrea JM (1950) On the isotopic chemistry of carbonates and a paleotemperature scale. J Chem Phys 18:849–857

McDonough W, Sun S (1995) The composition of the Earth. Chem Geol 120:223–253

Moore M, Chakhmouradian AR, Mariano AN, Sidhu R (2015) Evolution of rare-earth mineralization in the Bear Lodge carbonatite, Wyoming: mineralogical and isotopic evidence. Ore Geol Rev 64:499–521

Neave DA, Black M, Riley TR, Gibson SA, Ferrier G, Wall F, Broom-Fendley S (2016) On the feasibility of imaging carbonatite-hosted rare earth element (REE) deposits using remote sensing. Econ Geol 111:641–665

Nelson DR, Chivas AR, Chappell BW, McCulloch MT (1988) Geochemical and isotopic systematics in carbonatites and implications for the evolution of ocean-island sources. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 52:1–17

Ngwenya B (1994) Hydrothermal rare earth mineralisation in carbonatites of the Tundulu complex, Malawi: processes at the fluid/rock interface. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 58:2061–2072

Ni Y, Hughes JM, Mariano AN (1995) Crystal chemistry of the monazite and xenotime structures. Am Mineral 80:21–26

Nier AO (1938) The isotopic constitution of strontium, barium, bismuth, thallium and mercury. Phys Rev 54:275–278

Pearce N, Leng M (1996) The origin of carbonatites and related rocks from the Igaliko Dyke Swarm, Gardar Province, South Greenland: field, geochemical and CO–Sr–Nd isotope evidence. Lithos 39:21–40

Pearce N, Leng M, Emeleus C, Bedford C (1997) The origins of carbonatites and related rocks from the Gronnedal-Ika nepheline syenite complex, South Greenland; CO–Sr isotope evidence. Mineral Mag 61:515–529

Poitrasson F, Oelkers E, Schott J, Montel J-M (2004) Experimental determination of synthetic NdPO4 monazite end-member solubility in water from 21 °C to 300 °C: implications for rare earth element mobility in crustal fluids. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 68:2207–2221

Ray JS, Ramesh R (1999) A fluid-rock interaction model for carbon and oxygen isotope variations in altered carbonatites. J Geol Soc India 64:299–306

Ray JS, Ramesh R (2000) Rayleigh fractionation of stable isotopes from a multicomponent source. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 64:299–306

Richet P, Bottinga Y, Janoy M (1977) A review of hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulphur, and chlorine stable isotope enrichment among gaseous molecules. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 5:65–110

Ruberti E, Enrich GE, Gomes CB, Comin-Chiaramonti P (2008) Hydrothermal REE fluorocarbonate mineralization at Barra do Itapirapua, a multiple stockwork carbonatite, Southern Brazil. Can Mineral 46:901–914

Santos RV, Clayton RN (1995) Variations of oxygen and carbon isotopes in carbonatites: a study of Brazilian alkaline complexes. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 59:1339–1352

Snelling NJ (1965) Age determinations on three African carbonatites. Nature 205:491

Spötl S, Vennemann TW (2003) Continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometric analysis of carbonate minerals. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 17:1004–1006

Steiger RH, Jäger E (1977) Subcommission on geochronology: convention on the use of decay constants in geo- and cosmochronology. Earth Planet Sci Lett 36:359–362

Taylor HP, Frechen J, Degens ET (1967) Oxygen and carbon isotope studies of carbonatites from the Laacher See district, West Germany and the Alnö district, Sweden. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 31:407–430

Trofanenko J, Williams-Jones AE, Simandl GJ, Migdisov AA (2016) The nature and origin of the REE mineralization in the Wicheeda Carbonatite, British Columbia, Canada. Econ Geol 111:199–223

Verplanck PL, Mariano AN, Mariano A (2016) Rare earth element ore geology of carbonatites. Rev Econ Geol 18:5–32

Wall F (2000) Mineral chemistry and petrogenesis of rare earth-rich carbonatites with particular reference to the Kangankunde carbonatite, Malawi. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of London

Wall F (2014) Rare earth elements. In: Gunn A (ed) Critical metals handbook. Wiley, New York, pp 312–339

Wall F, Mariano A (1996) Rare earth minerals in carbonatites: a discussion centred on the Kangankunde Carbonatite, Malawi. In: Jones AP, Wall F, Williams CT (eds) Rare earth minerals: chemistry origin and ore deposits. Chapman and Hall, London, pp 193–226

Wall F, Zaitsev A (2004) Rare earth minerals in Kola carbonatites. In: Wall F, Zaitsev AN (eds) Phoscorites and carbonatites from mantle to mine: the key example of the Kola alkaline province. The Mineralogical Society, London, pp 341–373

Wall F, Barreiro BA, Spiro B (1994) Isotopic evidence for late-stage processes in carbonatites: rare earth mineralization in carbonatites and quartz rocks at Kangankunde, Malawi. Mineral Mag 58A:951–952

Wall F, Zaitsev AN, Mariano AN (2001) Rare earth pegmatites in carbonatites. J Afr Earth Sci 32:A35–A36

Williams-Jones A, Migdisov A, Samson I (2012) Hydrothermal mobilisation of the rare earth elements: a tale of “Ceria” and “Yttria”. Elements 8:355–360

Woolley AR (1969) Some aspects of fenitisation with particular reference to Chilwa Island and Kangankunde, Malawi. Bull Br Mus (Nat Hist) Mineral 2:189–219

Woolley AR (1991) The Chilwa alkaline igneous province of Malawi: a review. In: Kampunzu AB, Lubala RT (eds) Magmatism in extensional structural settings: the Phanerozoic African Plate. Springer, Berlin, pp 377–409

Woolley AR (2001) Alkaline rocks and carbonatites of the World. Part 3: Africa. The Geological Society, London

Xu C, Campbell IH, Allen CM, Chen Y, Huang Z, Qi L, Zhang G, Yan Z (2008) U–Pb zircon age, geochemical and isotopic characteristics of carbonatite and syenite complexes from the Shaxiongdong, China. Lithos 105:118–128

Zaitsev AN, Wall F, Le Bas MJ (1998) REE–Sr–Ba minerals from the Khibina carbonatites, Kola Peninsula, Russia: their mineralogy, paragenesis and evolution. Mineral Mag 62:225–250

Zaitsev AN, Demény A, Sindern S, Wall F (2002) Burbankite group minerals and their alteration in rare earth carbonatites: source of elements and fluids (evidence from C–O and Sr–Nd isotopic data). Lithos 62:15–33

Zaitsev AN, Terry Williams C, Jeffries TE, Strekopytov S, Moutte J, Ivashchenkova OV, Spratt J, Petrov SV, Wall F, Seltmann R, Borozdin AP (2015) Rare earth elements in phoscorites and carbonatites of the Devonian Kola Alkaline Province, Russia: examples from Kovdor, Khibina, Vuoriyarvi and Turiy Mys complexes. Ore Geol Rev 64:477–498

Zhang L, Liu J, Zhou H, Chen Z (1989) Oxygen isotope fractionation in the quartz-water-salt system. Econ Geol 84:1643–1650

Zhou L, Mavrogenes J, Spandler C, Li H (2016) A synthetic fluid inclusion study of the solubility of monazite-(La) and xenotime-(Y) in H2O–Na–K–Cl–F–CO2 fluids at 800 °C and 0.5 GPa. Chem Geol 442:121–129

Ziegler URF (1992) Preliminary results of geochemistry, Sm–Nd and Rb–Sr studies of post-Karoo carbonatite complexes in Southern Africa. Schweiz Mineral Petrogr Mitt 72:135–142

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) SoS RARE project (NE/M011429/1) and by NIGL (NERC Isotope Geoscience Laboratory) Project number 20135. Thanks are due to Hilary Sloane and Melanie Leng (NIGL) for C and O isotope data, Peter Greenwood (NIGL) for O isotope data in quartz, Barbara Barreiro (NIGL) for 87Sr/86Sr isotope data, Gary Jones and Vic Din (Natural History Museum, London) for major and trace element data, and Martin Smith (University of Brighton) for fluid inclusion images and discussion. Tony Mariano is thanked for contributing to Fig. 2. Two anonymous reviewers are thanked for contributing additional ideas to the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by Jochen Hoefs.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Broom-Fendley, S., Wall, F., Spiro, B. et al. Deducing the source and composition of rare earth mineralising fluids in carbonatites: insights from isotopic (C, O, 87Sr/86Sr) data from Kangankunde, Malawi. Contrib Mineral Petrol 172, 96 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-017-1412-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-017-1412-7