Abstract

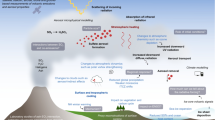

Volcanic eruptions are an important influence on decadal to centennial climate variability. Large eruptions lead to the formation of a stratospheric sulphate aerosol layer which can cause short-term global cooling. This response is modulated by feedback processes in the earth system, but the influence from future warming has not been assessed before. Using earth system model simulations we find that the eruption-induced cooling is significantly weaker in the future state. This is predominantly due to an increase in planetary albedo caused by increased tropospheric aerosol loading with a contribution from associated changes in cloud properties. The increased albedo of the troposphere reduces the effective volcanic aerosol radiative forcing. Reduced sea-ice coverage and hence feedbacks also contribute over high-latitudes, and an enhanced winter warming signal emerges in the future eruption ensemble. These findings show that the eruption response is a complex function of the environmental conditions, which has implications for the role of eruptions in climate variability in the future and potentially in the past.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Volcanic eruptions are a major driver of climate variability on a variety of timescales. Large tropical eruptions are capable of injecting sulphur dioxide into the stratosphere where it forms sulphate aerosol that may persist with an e-folding time of around 1 year, spreading globally with a resultant negative radiative forcing (Rampino and Self 1982; Robock 2000). After the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991, an estimated 20 Mt of SO\(_2\) was introduced into the stratosphere (Robock 2000) leading to a global cooling of around 0.3 °C (Lehner et al. 2016) and a reduction in global precipitation (Trenberth and Dai 2007). Repeated eruptions have shaped climate evolution, likely causing periods of cooling, such as during the 15–19th Centuries (Briffa et al. 1998; Schurer et al. 2014; Miller et al. 2012; Stoffel et al. 2015). More recently, a series of smaller eruptions may have offset a small portion of anthropogenic warming (Solomon et al. 2011; Vernier et al. 2011; Santer et al. 2014). Understanding the influence of volcanic eruptions therefore contributes to understanding climate variability (Timmreck 2012; Zanchettin 2017).

The climatic response to volcanic aerosols is complex. The negative radiative forcing induces several responses in the Earth system (Timmreck 2012; Zanchettin 2017), including expansion of sea-ice (Miller et al. 2012), changes in atmospheric (Robock and Mao, 1992) and ocean circulation (Ding et al. 2014), and perturbations to modes of variability (Lehner et al. 2016; Maher et al. 2015). These responses are partly dependent on the climate state prior to an eruption, as well as the location of the volcano and the season of eruption (Stevenson et al. 2017). While much attention has focused on short-term variability, less is known about the influence of longer-term changes in the background climate (Zanchettin et al. 2013). The future response to an eruption may be different because of changes in the climate system caused by anthropogenic warming. Aubry et al. (2016) have recently shown that warming-induced changes in the vertical structure of atmosphere (particularly changes in the tropopause height) would impact on the rise of volcanic plumes, but the impact of future changes on the radiative forcing and response to a volcanic eruption has not been quantified.

Here we analyse an ensemble of comprehensive Earth System model simulations of a large volcanic eruption to evaluate the climate system response to a large volcanic eruption in a future climate state. We performed an ensemble of simulations with the HadGEM2-ES Earth System model (HadGEM2 Development Team 2011; Collins et al. 2011) of a Tambora 1815 -like eruption in pre-industrial (Kandlbauer et al. 2013) and Representative Concentration Pathway 6.0 (RCP 6.0) conditions for the years AD1860 and AD2045, respectively. Tambora was chosen because it provides a very strong forcing which can be more easily separated from simulated internal variability.

2 Methods

To simulate the climatic impact of a volcanic eruption we use the UK Met Office Hadley Centre Global Environment Model 2 (HadGEM2-ES). This a coupled atmosphere-ocean general circulation model (GCM), which includes terrestrial and ocean carbon cycle components, interactive tropospheric aerosols and an interactive tropospheric chemistry scheme (HadGEM2 Development Team 2011; Collins et al. 2011). The atmospheric resolution of the model is 1.875 × 1.25° (longitude-latitude), with 38 vertical levels reaching to just over 39 km, with 11 levels above 15 km and resolving the lower stratosphere. The ocean resolution is 1° horizontally, but this increases in the latitudinal direction to 1/3° in the tropics, and has 40 unequally spaced vertical levels.

HadGEM2-ES includes an interactive sulphur cycle as well as representations of biomass burning, sea-salt, mineral dust and fossil fuel black and organic carbon aerosols (Bellouin et al. 2011). Biogenic aerosols do not vary and are prescribed as a fixed monthly climatology. Mineral dust and sea-salt are determined by interactively predicted emission rates. Sulphate precursor emissions are partly prescribed (anthropogenic, land dimethyl sulphide and volcanic degassing) and partly interactive (ocean dimethyl sulphide). Sulphate oxidation rates are calculated with the coupled tropospheric chemistry scheme (O’Connor et al. 2014). All other aerosols rely on prescribed monthly emissions. All aerosols interact with radiation, and all but mineral dust and black carbon influence cloud properties via the first and second indirect effects (Haywood and Boucher 2000). Stratospheric aerosols do not directly interact with clouds in the model and their implementation is described below. Land use is prescribed using a disturbed area fraction in each gridcell, which evolves through time. Vegetation coverage is parameterised using 5 plant functional types, and evolves interactively in the undisturbed fraction of each model gridcell.

HadGEM2-ES has been used extensively in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 5 (CMIP5) (Jones et al. 2011), for understanding past changes in climate (Hopcroft and Valdes 2015b), aerosols (Booth et al. 2012; Hopcroft et al. 2015) and atmospheric CH\(_4\) (Hopcroft et al. 2017), and for long-term future projections (Caesar et al. 2013). A high-top version of HadGEM2-ES (extending much further into the stratosphere) was not used as it shows little difference in the volcanic eruption response (Marshall et al. 2009), and is significantly more computationally expensive.

2.1 Volcanic forcing

Stratospheric aerosol formation and growth processes [e.g. Timmreck et al. (2010)] are not explicitly modelled, and so volcanic forcing is implemented in HadGEM2-ES by prescribing a stratospheric aerosol optical depth (AOD). The AOD values for the Tambora 1815 eruption used here (Crowley andUnterman 2013) are derived by correlation between ice core sulphate and electrical conductivity records and satellite observed stratospheric AODs (Sato et al. 1993). The stratospheric AOD is imposed on the climate model as a monthly time-series over four equal-area latitude bands (90–30°S, 30–0°S, 0–30°N, and 30–90°N) (Stott et al. 2006; Jones et al. 2011).

In HadGEM2-ES the stratospheric aerosol mass mixing ratio (mmr) is calculated to equal 1.917 × \(10^{12}\) kg m\(^{-2}\) per AOD. The aerosol mass is distributed over the stratospheric model levels which are defined at each timestep from the diagnosed position of the tropopause in each gridcell. The mass mixing ratio is defined based on the depth of the stratosphere and the input AOD. The prescribed mass of aerosol is therefore only dependent on the input AOD, but the thickness of the stratospheric aerosol layer and hence the mmr responds dynamically to temperature changes in the atmospheric column (Stott et al. 2006), with higher mmr values resulting from a higher tropopause for example. The height of the tropopause should not by itself have any influence on the resultant volcanic radiative forcing.

From the surface to 3 model levels above the dynamically diagnosed tropopause, ozone is simulated dynamically with a tropospheric chemistry scheme (O’Connor et al. 2014). Stratospheric halogen chemistry is not included, and so from the 4th level above the tropopause, stratospheric ozone is prescribed from an observationally-based zonally averaged climatology. Volcanically-induced changes in the stratospheric ozone (Solomon et al. 1998) are therefore not modelled.

2.2 Pre-industrial simulations

The Tambora eruption was first implemented in a pre-industrial simulation with HadGEM2-ES, with model boundary conditions relevant to the year AD 1860. These volcanic eruption simulations are described in detail by Kandlbauer et al. (2013). Briefly, this equilibrium pre-industrial simulation has prescribed greenhouse gas levels, CMIP5 recommended aerosol and other atmospheric chemistry emissions and reconstructed time-invariant land use. The CO\(_2\) concentration is 286 ppmv, and other details are given by Jones et al. (2011). We chose 5 random starting years from an initial 30-year control run to initiate 5 simulations with the Tambora eruption forcing. This “past” eruption ensemble shows a maximum global temperature decline of 1.0 ± 0.1 °C, consistent with other models (Raible et al. 2016), whilst the coupled terrestrial and oceanic carbon cycle components simulate an implied atmospheric CO\(_2\) perturbation of − 6 \(\pm\;2\)ppmv (Kandlbauer et al. 2013).

2.3 Future simulations

We placed a hypothetical future Tambora eruption in the year 2045 by performing new transient RCP 6 simulations with HadGEM2-ES. RCP 6 was chosen because it is less extreme than RCP8.5, but still includes significant future changes in the greenhouse gas forcing and aerosol loading. The RCP6 scenario leads to a global mean top of the atmosphere anthropogenic radiative forcing at 6 W m\(^{-2}\) by the year 2100, and is intermediate in terms of greenhouse gas forcing between the more extreme RCP8.5 and the RCP2.6 mitigation scenarios. The RCP6 scenario specifies increasing levels of greenhouse gases and changes in land-use and a delayed reduction in anthropogenic aerosol emissions. By 2045, at the onset of the hypothetical eruption, the CO\(_2\) concentration in RCP6 is 463 ppmv and is increasing at a rate of approximately 25 ppmv per decade.

The future simulations are initialised from the year 2040 of one of the CMIP5 RCP6 HadGEM2-ES simulations (Jones et al. 2011; Caesar et al. 2013). This give a relatively near-term future scenario. Since the climate is transient, one 20-year control run was performed, and four additional transient 8–10 year control (no-eruption) simulations around the time of the eruption were performed in order to allow a robust analysis of the volcanically-induced signal in this transient scenario. These control simulations include a constant background volcanic forcing which is equal to the background stratospheric aerosol AOD prescribed in the pre-industrial simulation (Jones et al. 2011), but all other forcings are transient. Five further transient simulations were performed but this time with the Tambora AOD forcing timeseries as used in the 'past' eruptions, and using variable initial conditions derived from the RCP6 control run, by initializing from different years within 5 years of the chosen starting point. All future simulations are segments of a longer term transient warming evolution, and as such are not expected to be in an equilibrium state.

3 Results

3.1 Radiation balance

The time series of net top of the atmosphere SW radiation shows a 15 Wm\(^{-2}\) reduction at the top of the atmosphere, and a smaller reduction in the future eruption response (Fig. 1). The downward surface SW radiation shows that the total surface SW at the surface is less in the future by around 3 Wm\(^{-2}\), a point we return to below. The overall response has a very similar structure in both time periods.

3.2 Surface temperature response

The annual mean near surface air temperature anomalies averaged over the 5 years after each eruption are shown in Fig. 2, where anomalies are masked if they are not significant at the 95% level according to a two-sided Student’s t-test. Here the variances are combined across ensemble members to give total variances using standard formulae (Section 2.3 of Upton and Cook (1996)). The 5 year-mean cooling is shown because a significant global temperature anomaly persists for nearly 10 years in response to the Tambora AOD perturbation (Kandlbauer et al. 2013) and, using more years for the climate anomaly means that the influence of interannual variability is less.

The 5 year mean cooling in the past eruption is −0.8 ± 0.1° C and this reduced by 14% to −0.7 ± 0.1 °C after the future eruption. In the future eruption there is a large region of no significant change over Europe, and the cooling in the north Atlantic and especially the Arctic is substantially less than found in the past eruption. In the Northern Hemisphere extra-tropics (> 45°N) the annual mean cooling reduces by 40% from − 1.2 ± 0.2 °C to − 0.7 ± 0.3 °C, and the winter (DJF) mean cooling reduces by 38% from −1.5 ± 0.4 °C to −0.9 ± 0.4 °C. Over both the tropics and Southern Hemisphere extra-tropics the cooling is 8% smaller in the future eruption.

3.3 Radiation budget

To understand the causes for the different response we first analysed the simulated radiation budgets using an offline decomposition of the contributions to the short-wave (SW) radiation balance (Taylor et al. 2007), termed the Approximate Partial Radiative Perturbation method (APRP). In APRP a simplified representation of the atmospheric column is used in each model gridbox to derive atmospheric scattering and absorption parameters that reproduce the monthly gridcell SW fluxes in each model simulation. The sensitivity of the fluxes to cloud and non-cloud constituents of the atmosphere can then be derived. APRP compares very well with the original Partial Radiative Perturbation method computed using high temporal frequency outputs from a GCM simulations of CO\(_2\)-induced warming (Taylor et al. 2007). As a result of its accuracy, APRP has been widely used to understand radiative feedbacks in models [e.g. Zelinka et al. (2014); Hopcroft and Valdes (2015a)].

We performed the APRP analysis using the monthly ensemble 5-year mean all-sky and clear-sky SW fluxes and cloud cover. The APRP was performed four times: for pre-industrial and future, with and without a simulated eruption. The differences between the two eruption and no-eruption results give the eruption influence on the SW radiation budget. The distributions for the surface, clear-sky atmospheric constituents and clouds are shown in Fig. 3. There is a globally averaged 8% reduction in the top of the atmosphere clear-sky SW radiation perturbation in the aftermath of the future eruption compared to the pre-industrial eruption. The zonally-average peak difference of 1 W m\(^{-2}\) is located over the tropics, with the largest differences emerging in the Atlantic and Indian ocean sectors (Fig. 3f). The change in the clear-sky SW response is largest over the ocean, where the albedo of the underlying surface is much lower than over the land.

Ensemble mean annual mean surface air temperature anomalies (°C) averaged over 5 years in the pre-industrial (left) and future RCP6 (right). Anomalies show eruption minus equivalent no-eruption simulations. The fields have been masked (grey shading) where they are not significant at the 95% level according to a 2-sided Student’s t-test. For the transient RCP6 simulations, the same years (i.e. with the same greenhouse gas concentrations) are compared

There are also significant changes in the SW cloud response over the same ocean basins (Fig. 3i). Comparing the no-eruption pre-industrial and RCP6 simulations, the cloud coverage is generally reduced by around 2–3%. The removal of high albedo cloud reveals darker underlying surface and hence would increase the effective volcanic forcing, because it makes the troposphere darker and so more prone to the influence from increases in stratospheric aerosols. This is the opposite of the modelled response over the Atlantic and Indian Ocean basins. These regions correspond with the areas of largest relative increase in sulphate aerosol loading and biomass burning aerosol, as indicated by increased aerosol optical depth shown in Fig. 4. Since both sulphate and biomass burning aerosols can influence the cloud properties via parameterised indirect aerosol effects in HadGEM2-ES, the simulated changes in cloud properties between the pre-industrial and RCP6 are consistent with the large increase in aerosol loading over these regions. Therefore, changes in cloud top effective particle radius and liquid water content can in regions, reduce the effective volcanic forcing by increasing the cloud top albedo.

Idealised offline calculations were performed using the SOCRATES [Suite Of Community RAdiative Transfer codes based on Edwards and Slingo: Manners et al. (2015)] to evaluate the reasons for the reduced clearsky and cloud SW terms shown in Fig. 3. SOCRATES is an updated version of the radiation code used in the Unified Model, including in HadGEM2-ES (Edwards and Slingo 1996). As the largest change in the SW flux is over the Indian and Atlantic oceans, we configured a single column profile with appropriate conditions. We prescribed a uniform cloud layer from 400–150 mbar, with optical properties derived from HadGEM2-ES effective cloud top radius and liquid water content. A single uniform layer of tropospheric sulphate [partitioned into aitken and accumulation modes with a ratio of 3:2, as in Fig. 5 of Bellouin et al. (2007)] is distributed from the surface to 500 mbar. The solar zenith angle is set to 55\(^\circ\), corresponding to the insolation weighted-mean (Cronin 2014). Paired simulations are performed with the second including a single volcanic stratospheric aerosol layer with a mixing ratio chosen to represent the volcanic aerosol layer of approximately the density of Tambora eruption as simulated with HadGEM2-ES. In the future RCP6 eruption the following changes are considered relative to the pre-industrial base case:

-

1.

Concentrations of CO\(_2\) and CH\(_4\) are increased from pre-industrial to RCP6 AD 2045 levels.

-

2.

Tropospheric sulphate loading increases by a factor of 1.5–4 over much of the northern hemisphere, with larger 5–15 fold increases in the vicinity of Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and China. We imposed a factor of 4 increase from a tropical mean in the pre-industrial control of 1.9 \(\times 10^{-6}\) kg m\(^{-2}\).

-

3.

Cloud fraction over the tropical ocean decreases from 65 to 64%.

-

4.

Cloud particle effective radii decrease by as much as 4.0 \(\upmu\)m over parts of the tropics. We imposed a change of − 2.5 \(\upmu\)m.

-

5.

Cloud liquid water content increase up to 1.0–3.0 \(\times\;10^{-6}\) kg kg\(^{-1}\). We imposed a change of 2.0 \(\times\;10^{-6}\) kg kg\(^{-1}\).

Top of the atmosphere annual mean downwards short-wave radiative responses for the pre-industrial and RCP6 (future) simulations. Averages are for 5 years and across ensemble members. a, d, g Show the eruption response (abbreviated as \(\Delta\)) for pre-industrial conditions, and b, e, h show the equivalent maps for the RCP6 eruption response. c, f, i Show the difference in the eruption response between the RCP6 and pre-industrial configurations

HadGEM2-ES pre-industrial and RCP6.0 outputs of aerosol loading, cloud top effective particle radius and cloud liquid water were calculated from CMIP5 archive, as they were not saved in our HadGEM2-ES simulations. Together the changes listed above reduce the net downwards SW flux anomaly in response to the volcanic eruption by 21% at the top of the atmosphere, as shown in Fig. 5. The principal causes of the difference between the two time periods are the direct aerosol effect from increase tropospheric sulphate, and the decreased effective particle radius. Isolating the direct sulphate effect leads to an 11% reduction in effective volcanic forcing and the effective particle radius decrease is responsible for the majority of the extra 10% reduction to 21%.

A similar experiment with unchanging tropospheric sulphate, but a 4-fold increase in biomass burning aerosol, representative of the increase in this aerosol over the tropical Atlantic (shown in Fig. 4), leads to a 14% reduction in the effective volcanic radiative forcing in the RCP6 simulation relative to the pre-industrial eruption response. This weaker response is consistent with the smaller difference between the eruption response in the RCP6 and pre-industrial eruption shown in Fig. 3f for the tropical Atlantic where the most significant difference in terms of tropospheric aerosols, is due to biomass burning rather than sulphate.

The impacts from reduced cloud coverage and changes in land albedo were tested and have a very minor impact on the effective SW volcanic forcing. Overall the reduced effective volcanic forcing is consistent, with the global 8% reduction in HadGEM2-ES, and strongly suggests that the future changes in the short-wave radiation budget reduce the volcanic response of the climate system in an anthropogenically perturbed atmosphere in comparison with a pre-industrial state.

3.4 Sea-ice

Post-eruption sea-ice expansion (shown in Fig. 6) also has a major effect on the surface temperature response through the albedo and water vapour effects (Budyko 1969; Sellers 1969). In the future simulation, there is substantially less sea-ice before the eruption because the climate is up to 10°C warmer in the Arctic. This means that the positive feedback in response to sea-ice expansion after an eruption is smaller in both hemispheres, consistent with past work on sea-ice. The future eruption surface albedo impact on SW radiation averaged north of 45°N is less than half that in the past eruption at − 0.34 W m\(^{-2}\) versus − 0.71 W m\(^{-2}\), with a similar reduction from − 0.12 to − 0.08 W m\(^{-2}\) in the southern extra-tropics.

Annual mean vertical profile of net downward short-wave radiation in response to stratospheric aerosols calculated using a single-column offline radiative transfer model (Edwards and Slingo 1996). The differences between the pre-industrial and RCP6 are mostly attributed to increased tropospheric aerosol loading (i.e. below 500 mbar), as described in detail in Sect. 3.3

Changes in sea-ice can also impact the long-wave (LW) radiation budget. The outgoing LW radiation at the tropopause minus the surface north of 45\(^\circ\)N is correlated with the spatial pattern of sea-ice change (Fig. 6), and shows a reduction by − 3.6 W m\(^{-2}\) in response to the past eruption, but by only − 2.7 W m\(^{-2}\) in the future eruption. There is a similar pattern for southern extra-tropics (− 1.6 W m\(^{-2}\) in the past eruption and − 1.2 W m\(^{-2}\) in the future).

3.5 Dynamical response

The eruption forcing also induces a dynamical response in the atmosphere as indicated by the different spatial pattern of cooling in Fig. 2. The stratospheric zonal wind in the Northern Hemisphere strengthens substantially in the early winter (November to December) in the future eruption, prior to substantial winter warming which occurs in the first post-eruption winter (Fig. 6). This response in the two time periods is compared in a Hovmöller plot (Fig. 7) of the zonal wind eruption minus no-eruption anomaly averaged from 40–70\(^\circ\)N and 60\(^\circ\)W–40\(^\circ\)E. The future eruption ensemble shows a stronger zonal wind response, which also propagates further into the troposphere.

Ensemble mean anomalies of the first post-eruption early winter (November-December mean) sea-ice albedo (%) and zonal wind at 20 hPa (m s\(^{-1})\) and whole winter (December-January-February mean) sea-level pressure (hPa) and surface (1.5 m) air temperature (K) response. The left column shows the pre-industrial eruption response (Kandlbauer et al. 2013), and the right column shows the future RCP6 eruption response

In response to the future eruption, the warming in Northern Europe is greater than 3 \(^\circ\)C. This warming effect is much less evident in the past eruption. The early-winter sea-ice gain in the future eruption is the main difference between the past and future eruption simulations, with expansion throughout the year confined to the margins of sea-ice in the past eruption. In the future simulations, the eruption-induced cooling causes an expansion in sea-ice much further north (Fig. 6).

Ensemble mean Hovmöller diagrams of the zonal wind anomaly in m s\(^{-1}\) (eruption minus no-eruption simulations). The zonal wind is averaged from 40–70\(^\circ\)N and 60\(^\circ\)W–40\(^\circ\)E. Anomalies are masked grey where they are not significant at the 95% level according to a two-sided Student’s t-test

Sea-ice changes are thought to have an influence on mid-latitude climate by modifying upward wave propagation (Kim et al. 2014). Years with low sea-ice have enhanced wave-propagation into the stratosphere, a weaker polar vortex, a negative shift in the Arctic-Oscillation and mid-latitude winter cooling (Kim et al. 2014). The eruption-induced sea-ice gain resembles the reverse of this process, with sea-ice expansion causing mid-latitude winter warming, but only in the future eruption.

As for Fig. 6, but showing the response in atmosphere-only simulations in which only sea-ice is perturbed, so that both direct stratospheric aerosol effects and sea-surface temperature changes are not included

To quantify the relative influence of surface conditions versus changes in the radiative forcing in the upper atmosphere on the winter warming, we performed further simulations with the atmospheric component of HadGEM2-ES. To simplify the analysis, both the dynamic vegetation and tropospheric chemistry schemes were also deactivated. These simulations are 30 years long and use prescribed monthly sea-surface temperature (SST) and sea-ice fields calculated from the respective ensemble means. Here we only modify the sea-ice for the eruption simulation, isolating its impact on the surface temperature response. These simulations employed constant pre-industrial boundary conditions otherwise, except in the future simulations, for which we increased atmospheric CO\(_2\) to the value of 463ppmv (close to the CO\(_2\) concentration in year 2045 under RCP6 scenario).

Boreal summer (JJA) precipitation anomalies (mm day\(^{-1}\)) for the past (left) and future (right), calculated using the ensemble-mean eruption minus no-eruption response using the 2 summers following the eruption. Values are masked where they are not significant at the 95% level according to the 2-sided Student’s t-test

The resultant changes in the northern hemisphere winter circulation and surface air temperatures are shown in Fig. 8. The emergence of mid-latitude warming in the second half of winter only in response to the future eruption is replicated here as in the fully coupled simulations. We therefore conclude that changes in surface conditions, most likely the relatively extreme high-latitude sea-ice expansion in the early winter in the future eruption may be responsible for this behaviour in the model. However, more model ensemble members are required to comprehensively evaluate the robustness of the results in the coupled model, and to clarify the mechanisms underlying this aspect of the model’s response (Pausata et al. 2016; Bittner et al. 2016) (Table 1).

These simulations show that the different spatial patterns of sea-ice expansion may be able to explain the post-eruption winter warming response simulated in response to the future eruption. Since the winter-warming persists for at least 5 years after the future eruption, it suggests that the mechanism involved is distinct [e.g. Zanchettin et al. (2012, 2013)] from that which causes the 1-year post-eruption winter-warming observed during the past century (Robock and Mao 1992; Zambri and Robock 2016). This mechanism requires further evaluation with a larger ensemble of eruption simulations.

3.6 Other earth system impacts

Although cooling is reduced for a future volcanic eruption, much of any societally-relevant climatic impact stems from changes to the hydrological cycle. Thermodynamic arguments would predict a reduced hydrological response in the future eruption because of the more limited cooling, but the precipitation change is more complex, reflecting the role of dynamical changes. In central Europe the pre-industrial eruption simulation shows increased summer cloudiness and precipitation in agreement with observations from 1816 (Auchmann et al. 2012) and mechanistic arguments (Wegmann et al. 2014). The future simulation shows a similar though less widespread response (Fig. 9). In contrast, a significant precipitation reduction over tropical South America after the pre-industrial eruption is not simulated in the future eruption response, because of a more muted sea-surface temperature response in the tropical Atlantic (Fig. 10). This is caused by the reduced effective volcanic forcing in this region discussed in Sect. 3.3.

The natural carbon cycle is also sensitive to volcanic eruptions [e.g. Keeling et al. (1995); Jones and Cox (2001)]. The model shows terrestrial net primary productivity (NPP) anomalies in the future eruption that are 2.6 times larger than for the pre-industrial eruption (Fig. 11 and Table 2). The pre-industrial simulation shows a net draw-down of carbon dioxide (CO\(_2\)) of 6.4 ppmv (Kandlbauer et al. 2013), whilst the ensemble mean value for the future eruption is nearly 50% larger at 9.4 ppmv. This is mostly driven by an increase in terrestrial net primary productivity (NPP) in the future simulations, which is 2.6 times larger than the perturbation following the pre-industrial eruption. This is caused by an opposite sign in the change of global gross primary productivity (GPP) i.e. photosynthesis increases on a global average after the future eruption as detailed in Table 2. Given the warmer climate state, a cooling in the tropics helps to increase productivity as it reduces the land area exposed to greater than optimal temperatures for photosynthesis. Further, in the higher CO\(_2\) atmosphere, the productivity is elevated by the CO\(_2\) fertilisation effect, which means that similar relative anomalies lead to larger absolute changes in carbon fluxes. The regional sensitivity of the carbon cycle is also altered.

4 Discussion

Tropospheric aerosol precursor emissions rose over the historical period, but are projected to decline in the coming century (Moss et al. 2010), see e.g. http://tntcat.iiasa.ac.at/RcpDb for comparisons. The RCP6 scenario is an intermediate in terms of the anthropogenic radiative forcing by AD 2100, but has the slowest decrease in sulphate emissions and an increase in biomass burning that distinguishes it from the more fossil fuel intensive RCP8.5 scenario. Thus the absolute course of tropospheric aerosols is subject to much uncertainty. The nature of the aerosol-cloud interaction strength is also highly uncertain (Carslaw et al. 2013). Although, HadGEM2-ES is one of the best models in CMIP5 [see Fig. 9.7 by Flato et al. (2013)], and is close to the mean response (in terms of aerosol effects) when compared with 8 other models used in CMIP5 (Zelinka et al. 2014), the strength of the aerosol-cloud interactions in the model are controversial (Booth et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2012). A newer version of the Met Office Unified model which predicts particle size distributions, shows weaker indirect effects (aerosol-cloud interactions) over the oceans and stronger effects over land (Bellouin et al. 2013). This change in the spatial pattern of the indirect effects would have an influence on the efficacy of the volcanic radiative forcing in a future, aerosol-laden atmosphere, in comparison with a cleaner, pre-industrial atmosphere.

Although Aubry et al. (2016) show that the amount of volcanic sulphur dioxide reaching the stratosphere is sensitive to climatic warming, they showed that this is effect is weakest for the largest eruptions. Therefore, it seems that for an eruption of the magnitude of Tambora, this is probably less important. Related to this, the stratospheric AOD reconstruction that we use is relatively crude, as it is configured with just 4 latitude bands and no vertical variation. The precise representation of the structure of the stratospheric aerosol appears to be important (Toohey et al. 2014), so it would be worth examining the implications for the climatic response, from uncertainty in the knowledge of the structure of the aerosol layer. What may be more crucial though, is the altered rates of chemical conversion of aerosol precursors to sulphate aerosols in a warmer climate (with potential cooling in the stratosphere). This is beyond the scope of the present study, and could be the subject of further research with a more sophisticated scheme.

Changes in tropospheric aerosols may also be important in past time periods. For example, during the last glacial maximum (LGM, 21,000 years BP) there was a global 2–4-fold increase in the dust cycle intensity (Lambert et al. 2015), which would have increased the albedo of the troposphere in a similar manner as for the future increase in man-made aerosols. Conversely, the global cooling of 3–5 \(^\circ\)C relative to the pre-industrial during the LGM (Shakun et al. 2012) would have lowered the tropopause by up to 1.5 km, so that smaller more frequent eruptions would more easily penetrate the stratosphere, following the mechanism outlined by Aubry et al. (2016).

Summers are nearly ice-free under RCP6 in 2050 in these simulations. Further into the future, the sea-ice response to an eruption will be larger given projected further reductions in annual sea-ice extent (Stroeve et al. 2012). In a sufficiently warm future state with no sea-ice year-round, an eruption might not cause any significant sea-ice formation. In this case, other cloud-related climate feedbacks may instead be more important (Abbot and Tziperman 2008).

Our conclusions regarding the dynamical post-eruption response are supported by separate atmosphere-only simulations. Despite this, the small ensemble size of our study, hinders comprehensive conclusions regarding the dynamical responses in the northern hemisphere extra-tropics. Whilst the differences in temperature anomalies between the pre-industrial and future (as shown in Fig. 2) strongly suggest dynamical differences between the two time periods, the limited size of our ensemble does not allow us to unequivocally rule out internal model variability. Therefore, a more thorough analysis of this aspect of the modelled response would require further simulations to produce a larger ensemble size (Pausata et al. 2015; Bittner et al. 2016).

There are a limited number of observed large eruptions, as well as difficulties in separating El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) related climate effects from volcanic eruptions. Further, general circulation models (including HadGEM2-ES) had been thought to under-estimate the observed post-eruption northern hemisphere winter dynamical response (Driscoll et al. 2012; Charlton-Perez et al. 2013; Bittner et al. 2016), but restricting the analysis to the first post-eruption winter and only the strongest volcanic eruptions alters this (Bittner et al. 2016; Zambri and Robock 2016). Nevertheless, an improved understanding of the dynamical response to volcanic eruptions is required to clarify the possibility of enhanced winter warming in response to future eruptions. Idealised eruption simulations with a larger range of models (Zanchettin et al. 2016) will contribute to this issue.

5 Conclusions

Independent of several uncertainties associated with the winter warming response or the exact timing of future warming and sea-ice decline, our results show for the first time that a future large eruption will have a smaller cooling signal than would be expected in a pre-industrial state. The dominant contributing factors to the reduced cooling (increased tropospheric planetary albedo and sea-ice reduction) are both robust features of climate model projections across a range of different coupled models (Stroeve et al. 2012). However, they have not been evaluated in the context of future climate response. The lack of previous climate model-based analysis is partly because future climate change scenarios do not include volcanic eruptions despite there being about a 30% probability of a Tambora-scale eruption by 2100 (Deligne et al. 2010). The interaction between tropospheric planetary albedo and the magnitude of the direct volcanic aerosol radiative forcing has not been reported previously to our knowledge. This diminished volcanic response may, depending on the eruption magnitude, be further enhanced by the proposed effect of the tropopause height on the penetration of smaller eruption plumes (Aubry et al. 2016).

Even given a reduced cooling signal, the impacts on society and ecosystems from a large eruption are in places likely to be stronger in the future because of the intensified hydrological response. More detailed assessments of the likely climate-induced impacts are required to translate the identified mechanisms into appropriate adaptation strategies.

References

Abbot D, Tziperman E (2008) Sea ice, high-latitude convection, and equable climates. Geophys Res Lett 35(L03702)

Aubry T, Jellinek A, Degruyter W, Bonadonna C, Radic V, Clyne M, Quainoo A (2016) Impact of global warming on the rise of volcanic plumes and implications for future volcanic aerosol forcing. J Geophys Res 121

Auchmann R, Brönnimann S, Breda L, Bühler M, Spadin R, Stickler A (2012) Extreme climate, not extreme weather: the summer of 1816 in Geneva, Switzerland. Clim Past 8:325–335

Bellouin N et al (2013) Impact of the modal aerosol scheme GLOMAP-mode on aerosol forcing in the Hadley Centre Global Environmental Model. Atmos Chem Phys 13:3027–3044

Bellouin N, Boucher O, Haywood J, Johnson C, Jones A, Rae J, Woodward S (2007) Improved representation of aerosols for HadGEM2. Hadley Centre Technical Note 73

Bellouin N, Rae J, Jones A, Johnson C, Haywood J, Boucher O (2011) Aerosol forcing in the CMIP5 simulations by HadGEM2-ES and the role of ammonium nitrate. J Geophys Res 116(D20206)

Bittner M, Timmreck C, Schmidt H, Toohey M, Kruger K (2016) The impact of wave-mean flow interaction on the Northern Hemisphere polar vortex after tropical volcanic eruptions. J Geophys Res 121

Booth B, Dunstone N, Halloran P, Andrews T, Bellouin N (2012) Aerosols implicated as a prime driver of twentieth-century North Atlantic climate variability. Nature 484(7393):228–232

Briffa K, Jones P, Schweingruber F, Osborn T (1998) Influence of volcanic eruptions on Northern Hemisphere summer temperature over the past 600 years. Nature 393:450–455

Budyko M (1969) The effect of solar radiation variations on the climate of the earth. Tellus 21:611–619

Caesar J, Palin E, Liddicoat S et al (2013) Response of the HadGEM2 earth system model to future greenhouse gas emissions pathways to the year 2300. J Clim 26:3275–3284

Carslaw K, Lee L, Reddington C, Pringle K, Rap A, Forster P, Mann G, Spracklen D, Woodhouse M, Regayre L, Pierce J (2013) Large contribution of natural aerosols to uncertainty in indirect forcing. Nature 503:67–71

Charlton-Perez A, Baldwin M, Birner T, Black R, Butler A et al (2013) On the lack of stratospheric dynamical variability in low-top versions of the CMIP5 models. J Geophys Res 118:1–12

Collins W, Bellouin N, Doutriaux-Boucher M, Gedney N, Halloran P, Hinton T, Hughes J, Jones C, Joshi M, Liddicoat S, Martin G et al (2011) Development and evaluation of an Earth-system model-HadGEM2. Geosci Model Dev 4:1051–1075

Cronin T (2014) On the choice of average solar zenith angle. J Atmos Sci 71:2994–3003

Crowley T, Unterman M (2013) Technical details concerning development of a 1200 yr proxy index for global volcanism. Earth Syst Sci Data 5:187–197

Deligne N, Coles S, Sparks R (2010) Recurrence rates of large explosive volcanic eruptions. J Geophys Res 114:B06203

Ding Y, Carton J, Chepurin G, Stenchikov G, Robock A, Sentman L, Krasting J (2014) Ocean response to volcanic eruptions in Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 5 simulations. J Geophys Res Oceans 119:5622–5637

Driscoll S, Bozzo A, Gray L, Robock A, Stenchikov G (2012) Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 5 (CMIP5) simulations of climate following volcanic eruptions. J Geophys Res 117:D17105

Edwards J, Slingo A (1996) Studies with a flexible new radiation code. I: choosing a configuration for a large-scale model. Q J R Met Soc 122:689–719

Flato G, Marotzke J, Abiodun B, Braconnot P, Chou S, Collins W, Cox P, Driouech F, Emori S, Eyring V, Forest C, Gleckler P, Guilyardi E et al (2013) Evaluation of climate models. In: Stocker T, Qin D, Plattner G-K, Tignor M, Allen S, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley P (eds) Climate Change 2013: the physical science basis: contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: CUP

HadGEM2 Development Team (2011) The HadGEM2 family of Met Office Unified Model climate configurations. Geosci Model Dev. 4:7233–757

Haywood J, Boucher O (2000) Estimates of the direct and indirect radiative forcing due to tropospheric aerosols: a review. Rev Geophys 38(4):513–543

Hopcroft P, Valdes P (2015a) How well do simulated last glacial maximum tropical temperatures constrain equilibrium climate sensitivity? Geophys Res Lett 42(13):5533–5539

Hopcroft P, Valdes P (2015b) Last glacial maximum constraints on the earth system model HadGEM2-ES. Clim Dyn 45(5):1657–1672

Hopcroft P, Valdes P, O’Connor F, Kaplan J, Beerling D (2017) Understanding the glacial methane cycle. Nat Commun 8(14383)

Hopcroft P, Valdes P, Woodward S, Joshi M (2015) Last glacial maximum radiative forcing from mineral dust aerosols in an Earth System model. J Geophys Res 120(16):8186–8205

Jones C, Cox P (2001) Modeling the volcanic signal in the atmospheric CO\(_2\) record. Global Biogeochem Cycles 15(2):453–465

Jones C, Hughes J, Bellouin N, Hardiman S, Jones G, Knight J, Liddicoat S, O’Connor F, Andres R, Bel C, Boo K-O, Bozzo A, Butchart N, Cadule P, Corbin K, Doutriaux-Boucher M, Friedlingstein P, Gornall J, Gray L, Halloran P, Hurtt G, Ingram W, Lamarque J-F et al (2011) The HadGEM2-ES implementation of CMIP5 centennial simulations. Geosci Model Dev 4:543–570

Kandlbauer J, Hopcroft P, Valdes P, Sparks R (2013) Climate and carbon cycle response to the 1815 Tambora volcanic eruption. J Geophys Res 118:12497–12507

Keeling C, Whorf T, Wahlen M, van der Plicht J (1995) Interannual extremes in the rate of rise of atmosphere carbon dioxide since 1980. Nature 375:666–670

Kim B-M et al (2014) Weakening of the stratospheric polar vortex by Arctic sea-ice loss. Nat Commun 5:4646

Lambert F et al (2015) Dust fluxes and iron fertilization in Holocene and last glacial maximum climates. Geophys Res Lett 42:6014–6023

Lehner F, Schurer A, Hegerl G, Deser C, Frolicher T (2016) The importance of ENSO phase during volcanic eruptions for detection and attribution. Geophys Res Lett 43

Maher N, McGregor S, England M, Sen Gupta A (2015) Effects of volcanism on tropical variability. Geophys Res Lett 42:6024–6033

Manners J, Edwards J, Hill P, Thelen J-C (2015) SOCRATES Technical Guide Suite Of Community RAdiative Transfer codes based on Edwards and Slingo. Technical report, Met Office

Marshall A, Scaife A, Ineson S (2009) Enhanced seasonal prediction of european winter warming following volcanic eruptions. J Clim 22:6168–6180

Miller G, Geirsdottir A, Zhong Y, Larsen D, Otto-Bleisner B, Holland M, Bailey D et al (2012) Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks. Geophys Res Lett 39:L02708

Moss R et al (2010) The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 463:747–756

O’Connor F, Johnson C, Morgenstern O, Abraham N, Braesicke P, Dalvi M, Folberth G, Sanderson M, Telford P, Voulgarakis A, Young P, Zeng G, Collins W, Pyle J (2014) Evaluation of the new UKCA climate-composition model—part 2: the troposphere. Geosci Model Dev 7:41–91

Pausata F, Messori G, Zhang Q (2016) Impacts of dust reduction on the northward expansion of the African monsoon during the Green Sahara period. Earth Planet Sci Lett 434:298–307

Pausata FSR, Grini A, Caballero R, Hannah A, Seland O (2015) High-latitude volcanic eruptions in the norwegian earth system model: the effect of different initial conditions and of the ensemble size. Tellus B 67(1):26728

Raible C, Bronnimann S, Auchmann R, Broahan P et al (2016) Tambora 1815 as a test case for high impact volcanic eruptions: earth system effects. WIREs Clim Change 7:569–589

Rampino M, Self S (1982) Historic Eruptions of Tambora (1815), Krakatau (1883), and Agung (1963), Their Stratospheric Aerosols, and Climatic Impact. Quat Res 18:127–143

Robock A (2000) Volcanic eruptions and climate. Rev Geophys 38:191–219

Robock A, Mao J (1992) Winter warming from large volcanic eruptions. Geophys Res Lett 19:2405–2408

Santer B, Bonfils C, Painter J, Zelinka M, Mears C, Solomon S, Schmidt G, Fyfe J, Cole J, Nazarene L, Taylor K, Wentz F (2014) Volcanic contribution to decadal changes in tropospheric temperature. Nat Geosci 7(3):185–189

Sato M, Hansen J, McCormick M, Pollack J (1993) Stratospheric aerosol optical depths, 1850–1990. J Geophys Res 98(D12):22987–22994

Schurer A, Tett S, Hegerl G (2014) Small influence of solar variability on climate over the past millennium. Nat Geosci 7:104–108

Sellers W (1969) A global climatic model based on the energy balance of the earth-atmosphere system. J Appl Met 8:392–400

Shakun J et al (2012) Global warming preceded by increasing carbon dioxide concentrations during the last deglaciation. Nature 484:49–54

Solomon S, Daniel J, Neely R III, Vermier J-P, Duton E, Whomason L (2011) The persistently variable “background” stratospheric aerosol layer and global climate change. Science 333:866–869

Solomon S, Portmann R, Garcia R, Randel W, Wu F, Nagatani R, Gleason J, Thomason L, Poole L, McCormick M (1998) Ozone depletion at mid-latitudes: coupling of volcanic aerosols and temperature variability to anthropogenic chlorine. Geophys Res Lett 25:1871–1874

Stevenson S, Fasullo J, Otto-Bliesner B et al (2017) Role of eruption season in reconciling model and proxy responses to tropical volcanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci. Early edition

Stoffel M, Khodri M, Corona C, Guillet S, Poulain V, Bekki S, Guiot J et al (2015) Estimates of volcanic-induced cooling in the Northern Hemisphere over the past 1,500 years. Nat Geosci 8:784–790

Stott P, Jones G, Lowe J, Thorne P et al (2006) Transient climate simulations with the HadGEM1 climate model: causes of past warming and future climate change. J Clim 19:2763–2782

Stroeve J, Kattsov V, Barrett A et al (2012) Trends in Arctic sea ice extent from CMIP5, CMIP3 and observations. Geophys Res Lett 39:L16502

Taylor K, Crucifix M, Braconnot P, Hewitt C, Doutriaux C, Broccoli A, Mitchell J, Webb M (2007) Estimating shortwave radiative forcing and response in climate models. J Clim 20:2530–2543

Timmreck C (2012) Modeling the climatic effects of large volcanic eruptions. WIREs Clim Change 3:545–564

Timmreck C, Graf H, Lorenz S, Niemeier U et al (2010) Aerosol size confines climate response to volcanic super-eruptions. Geophys Res Lett 37:L24705

Toohey M, Krüger M, Bittner C Timmreck, Schmidt H (2014) The impact of volcanic aerosol on the Northern Hemisphere stratospheric polar vortex: mechanisms and sensitivity to forcing structure. Atmos Chem Phys 14:13063–13079

Trenberth K, Dai A (2007) Effects of mount pinatubo volcanic eruption on the hydrological cycle as an analog of geoengineering. Geophys Res Lett 34:L15702

Upton G, Cook I (1996) Understanding statistics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Vernier J-P, Thomason L et al (2011) Major influence of tropical volcanic eruptions on the stratospheric aerosol layer during the last decade. Geophys Res Lett 38:L12807

Wegmann M, Bronnimann S, Bhend J, Franke J et al (2014) Volcanic influence on European summer precipitation through monsoons: possible cause for years without summer. J Clim 27:3683–3691

Zambri B, Robock A (2016) Winter warming and summer monsoon reduction after volcanic eruptions in Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 5 (CMIP5) simulations. Geophys Res Lett 43

Zanchettin D (2017) Aerosol and solar irradiance effects on decadal climate variability and predictability. Curr Clim Change Rep 3:150

Zanchettin D, Khodri M, Timmreck C, Toohey M, Schmidt A et al (2016) The model intercomparison project on the climatic response to volcanic forcing (VolMIP): experimental design and forcing input data for CMIP6. Geosci Model Dev 9:2701–2719

Zanchettin D, Timmreck C, Bothe OO (2013) Delayed winter warming: a robust decadal response to strong tropical volcanic eruptions? Geophys Res Lett 39(1–2):419–444

Zanchettin D, Timmreck C, Graf HFO (2012) Bi-decadal variability excited in the coupled ocean-atmosphere system by strong tropical volcanic eruptions. Clim Dyn 39(1–2):419–444

Zelinka M, Andrews T, Forster P, Taylor K (2014) Quantifying components of aerosol-cloud-radiation interactions in climate models. J Geophys Res 119:7599–7615

Zhang R, Delworth T, Sutton R et al (2012) Have aerosols caused the observed atlantic multidecadal variability? J Atmos Sci 70:1135–1144

Acknowledgements

We thank Jim Haywood and Andy Jones (Hadley Centre, Met Office) for discussion of the role of tropospheric planetary albedo. We acknowledge James Manners (Met Office) for providing SOCRATES. HadGEM2-ES simulations were performed using HECTOR and ARCHER, the UK national facility for high performance computing http://www.archer.ac.uk. We thank the Met Office Hadley Centre for sharing model setup for RCP6 simulations and NCAS for configuring HadGEM2-ES on ARCHER. We acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme’s Working Group on Coupled Modelling, which is responsible for CMIP, and we thank the Hadley Centre for producing and making available their model output. For CMIP the U.S. Department of Energy’s Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison provides coordinating support and led development of software infrastructure in partnership with the Global Organization for Earth System Science Portals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

POH was funded by a UK NERC projects NE/I010912/1 and NE/P002536/1, and by a Past Earth Network Feasibility Study. JK was supported by an AXA Research Fund PhD studentship. The model output analysed in this study are available from www.bridge.bris.ac.uk/resources/simulations. The source code for HadGEM2-ES is part of the UK Met Office Unified Model and is subject to Crown Copyright. The Met Office Unified Model is available for use under licence. For more information see http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/collaboration.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hopcroft, P.O., Kandlbauer, J., Valdes, P.J. et al. Reduced cooling following future volcanic eruptions. Clim Dyn 51, 1449–1463 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3964-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3964-7