Abstract

Background

Bariatric surgery is regarded as the most effective treatment of morbid obesity in adults. Referral patterns for bariatric surgery in adults differ among general practitioners (GPs), partially due to restricted knowledge of the available treatment options. Reluctance in referral might be present even stronger in the treatment of morbidly obese children.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the current practice of GPs regarding treatment of paediatric morbid obesity and their attitudes towards the emergent phenomenon of paediatric weight loss surgery.

Methods

All GPs enlisted in the local registries of two medical centres were invited for a 15-question anonymous online survey.

Results

Among 534 invited GPs, 184 (34.5%) completed the survey. Only 102 (55.4%) reported providing or referring morbidly obese children for combined lifestyle interventions. A majority (n = 175, 95.1%) estimated that conservative treatment is effective in a maximum of 50% of children. Although 123 (66.8%) expect that bariatric surgery may be effective in therapy-resistant morbid obesity, only 76 (41.3%) would consider referral for surgery. Important reasons for reluctance were uncertainty about long-term efficacy and safety. The opinion that surgery is only treatment of symptoms and therefore not appropriate was significantly more prevalent amongst GPs who would not refer (58.3% vs. 27.6%, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

There is a potential for undertreatment of morbidly obese adolescents, due to suboptimal knowledge regarding guidelines and bariatric surgery, as well as negative attitudes towards surgery. This should be addressed by improving communication between surgeons and GPs and providing educational resources on bariatric surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of morbid obesity in both adults and children has risen drastically worldwide over the past few decades, causing significant morbidity, mortality and financial costs for society [1,2,3,4,5]. In 2009, 2% and 0.5% of the children in the Netherlands were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) or morbidly obese (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2), respectively [5].

Combined lifestyle interventions (CLI) were developed as treatment for children and adolescents with (morbid) obesity. CLI should include at least dietary counselling, physical therapy and behavioural therapy, all provided by a specialized and dedicated multidisciplinary paediatric team [6, 7]. Although significant decrease of body mass index (BMI) has been reported in the short term, long-term benefits of CLI programs remain small [8, 9].

Consequently, several guidelines and position statements have been formulated to guide clinical decision-making which provide comparable indications, contra-indications and prerequisites for bariatric surgery in paediatric populations [10,11,12,13,14,15].

The Dutch Obesity Healthcare Standard (DOHS) advises paediatric bariatric surgery only in adolescents (i.e., age 16–17 years) who conform to a number of criteria, shown in Table 1 [14, 15]. In the Netherlands, paediatric bariatric surgery is exclusively performed in a clinical research setting.

Unfortunately, although bariatric surgery has been established as a highly effective treatment modality for a selected population of morbidly obese adults, a discrepancy has been noted between the number of patients eligible for bariatric surgery and the number of performed procedures [16,17,18,19,20,21]. This discrepancy has been attributed to several factors, such as knowledge of guidelines, knowledge of bariatric surgery and its outcomes, and referrer demographics [16,17,18,19,20,21]. The scarce literature available concerning referral patterns for children points towards an exceedingly conservative attitude, with a significant number of healthcare providers considering bariatric surgery in adolescents to be unacceptable and significant variations in opinions regarding prerequisites for surgery [22, 23].

To optimize paediatric obesity treatment, a potential discrepancy such as the aforementioned must be recognized and a possible educational gap filled. For this purpose, the practice, knowledge, and attitude of clinicians must be examined. In this light, GPs form an important group, as they are usually the first to encounter morbidly obese children and decide when to refer to a paediatrician. In addition, GPs play a crucial role in the follow-up of morbidly obese children, e.g., after (non-successful) combined lifestyle intervention (CLI) [14]. The aim of this study was to investigate the current practice, knowledge, and attitude of Dutch GPs regarding conservative and surgical treatment of morbidly obese children.

Methods

Questionnaire

An anonymous questionnaire was designed in an online platform for questionnaires and surveys (Survey Monkey Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA) (“Appendix”). The questionnaire consisted of 15 questions covering demographics, current practice and attitudes towards bariatric surgery in children and adolescents (defined as youngsters aged 12–17 years). Conditional branching was used to create a respondent specific custom path based on the respondent’s answers. Using this branching technique, the total amount of questions answered by a single respondent varied between 10 and 14 questions.

The fifteen items consisted of five dichotomous questions, one open question, five questions offered multiple choice with only one answer allowed, and four questions offered multiple choice allowing more than one answer. Of the latter, one question consisted of seven sub items, all to be scored on a Likert scale (range 1–5; never, seldom, sometimes, often, always). Some closed questions allowed textual remarks.

Participants

A sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula for categorical data, using an alpha level of 0.05, a margin of error of 0.05 and an estimate of variance of 0.25 [24]. For a representative sample of all the Dutch practice-based GPs (n = 9418; 7158 full-time equivalents), a minimum returned sample size of n = 364 was calculated. Consequently, a minimal sample size of n = 521 needs to be drawn from the population, assuming a response rate of 70%.

Selected for the online survey were all active GPs enlisted in the local registries of medical center A (n = 244) and medical center B (n = 290). Center A is a secondary and tertiary care hospital that holds the official Dutch training and education for GPs, and its local registry used for this survey consisted of only GPs affiliated to this official training. Center B is a secondary care hospital with bariatric surgery in adults as one of their main focuses; its local registry used for this survey consisted of all the GPs enlisted in their catchment area.

The GPs were invited for the online survey between July and September 2016. A single reminder was sent two to three weeks after the initial invitation.

Analysis

All completed surveys were used for analysis. Continuous data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical data are presented as number (percentage).

Categorical responses were compared using univariate analysis, χ2 or Fischer’s exact test where this was appropriate. Numerical responses were compared using independent samples t test. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used. The analyses were performed using IBM SPSS for Statistics (version 24.0.0.0).

Results

Of the 534 invited GPs, 184 respondents completed the online survey (34.5%). All respondents were licensed and practicing GPs. The majority of respondents had less than 5 children on treatment for morbid obesity at the time of filling out the questionnaire (Table 2).

Lifestyle and dietary advices were reported to be provided often or always by at least 90% of the respondents in the case of childhood morbid obesity (Fig. 1). Referral to sports or exercise programs was stated to be offered at least often by 70% of the respondents. The least frequent treatment modalities reported to be provided were cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and family treatment. When adequate GP treatment is defined as either referral to a paediatrician/specialized CLI team or self-provided high-intensity CLI including CBT and family treatment [6], only 55.4% (n = 102) of the respondents in this survey provides this adequate treatment.

Different norms of treatment success were observed among respondents. Thirty-eight respondents (20.6%) considered weight stabilization after 6–12 months as treatment success. The majority reported that weight loss is necessary after 12 months of treatment to consider the treatment a success, varying from 5% weight loss or more (n = 34, 18.5%) to at least 10% (n = 60, 32.6%), being the DHS definition for treatment success. Seventeen respondents (9.2%) noted to consider improvement of comorbidity as the parameter for treatment success. Thirty-five GPs (19.0%) stated they apply other (less objective) definitions, such as improvement of lifestyle or diet.

The vast majority (n = 175, 95.1%) estimated that the conservative treatment modalities offered are only effective in a maximum of 50% of the children. In general, 123 respondents (66.8%) answered they expect that bariatric surgery may be effective in children with therapy-resistant morbid obesity. Nevertheless, only 76 (41.3%) would consider referral for bariatric surgery in this population.

Different subgroups were analysed regarding both the expectation of effectiveness of bariatric surgery and the consideration for referral for surgery. Regarding the expectation of effectiveness, no differences were found in the following subgroups: different hospital regions (center A vs. center B, p = 0.707), years of working experience (<20 years vs. ≥20 years, p = 0.157), number of morbidly obese paediatric patients under treatment in practice (<5 vs. ≥5, p = 0.983). Willingness to refer for bariatric surgery did also not differ among the same subgroups: different hospital regions (p = 0.186), years of working experience (p = 0.291), number of morbidly obese paediatric patients under treatment in practice (p = 0.949).

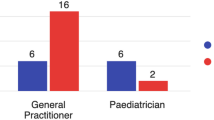

The 76 respondents who would consider referral for bariatric surgery were asked additional questions regarding their attitudes towards specific aspects of bariatric surgery in children. Fifty-one GPs (67.1%) stated a lower threshold for age than 16 years old, proposing a mean minimum age of 14.1 years (range 10–16 years) [14]. The majority of the respondents (n = 42, 55.3%) would consider referral in case of a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 (sex and age adjusted), while 20 respondents (26.3%) would already refer in case of a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2. Five respondents (6.6%) suggested a minimum BMI of 50 kg/m2, nine (11.8%) could not suggest a specific BMI threshold.

The presence of obesity-related comorbidity would influence the minimum BMI threshold for 66 respondents (86.8%). Type II diabetes mellitus was answered most often as comorbidity of influence (n = 62, 93.9%), followed by obstructive sleep apnea (n = 49, 74.2%) and hypertension (n = 45, 68.2%). Dyslipidemia and non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis were relevant for 36 (54.5%) and 25 (37.9%) respondents, respectively. Presence of a depressive disorder was mentioned as relevant by 30 respondents (45.5%), arthropathies were mentioned by 23 (34.8%).

The 108 respondents who answered not to consider referral for bariatric surgery were asked if certain circumstances would alter their opinion. Twenty-two respondents (20.4%) reported to consider referral after all in case of severe and/or therapy-resistant comorbidity.

All 184 respondents were asked about possible reasons for reluctance towards bariatric surgery in children and adolescents with morbid obesity. Uncertainty regarding complications in the long term was mentioned most (n = 132, 71.7%), followed by uncertainty regarding long-term efficacy (n = 119, 64.7%) and the notion that bariatric surgery only treats symptoms (n = 84, 45.6%) (Fig. 2).

There were no differences regarding uncertainty about complications or efficacy among the respondents who would refer for surgery compared to those who would not. However, the opinion that bariatric surgery is merely a treatment of symptoms as reason for reluctance was mentioned significantly more frequent by respondents who would not refer (n = 63, 58.3%) compared to the group that would refer (n = 21, 27.6%), p < 0.001. There were no differences in reasons for reluctance among the two hospital regions. Thirty-three respondents (17.9%) added other reasons to the list, varying from ‘the expectancy that near future will bring other solutions to the problem’ to ‘supply creates demand’.

Discussion

Main findings

The present study aimed to investigate the practice and attitudes of GPs regarding paediatric morbid obesity using a digital survey. In current treatment, lifestyle advices, dietary advices and sports or exercise programs (all provided by experts) are offered most often by the responding GPs. However, there is a significant discrepancy between the DHS and reported GP practice, implicating a relevant knowledge gap (Table 3).

Ninety-five percent of GPs estimated that their treatment is only sufficient in <50% of the patients. Although the majority of respondents think that bariatric surgery may be an effective last-resort treatment option, only 41.3% of the respondents would consider referral for surgery in this childhood population. This discrepancy may be related to non-efficacy-related factors, such as matters of principle. For example, one GP noted that ‘supply creates demand’, another GP noted that ‘the future will bring other solutions to the problem’, and many GPs (45.6%), especially those who would not refer, stated the notion that surgery only treats symptoms as reasons for reluctance.

Remarkably, the average minimum age threshold of 14.1 years proposed by GPs that would consider referral was significantly lower than was found in a 2010 survey conducted amongst GPs and paediatricians in the United States, where physicians who would refer for bariatric surgery believed a minimum age of 16.9 years was necessary [23]. This might indicate that the GPs open to referral for bariatric surgery are becoming more progressive in their attitudes, while the majority of GPs remain reluctant to refer morbidly obese children or adolescents for bariatric surgery.

Reasons for reluctance

Frequently mentioned reasons for reluctance were uncertainty regarding complications in the long term and uncertainty regarding long-term efficacy (71.7 and 64.7%, respectively). Although bariatric surgery is effective and safe both in the short and long term in an adult population [25,26,27,28,29], there indeed is a scarcity of long-term data in the paediatric population, which must be accommodated by future research [30]. On the other hand, a significant proportion of GPs reported reluctance due to the aforementioned personal notions, which should be addressed through educational means, to assure proper and uniform care for therapy-resistant morbid obese adolescents.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this study is that the population used for this survey is representative for the different Dutch GP practices, combining GPs affiliated with both secondary and tertiary medical centers. Since there are no Dutch tertiary centers practicing bariatric surgery on a regular base, the subgroup GPs affiliated to the tertiary center in the present study is assumed to be less experienced in bariatric care (but may be more updated on innovative treatments since they hold the GP training). Due to the design of this study, GPs affiliated to a secondary center without bariatic surgery have not been included, which may lead to a certain amount of bias. However, in a small country such as the Netherlands, most GPs are in close proximity to a bariatric center in daily practice.

Another strength of this survey is that reasons for reluctance were reported by all respondents, offering more insight in reasons why GPs would not refer.

Self-selection bias is one of the limitations of this study, accompanied by the fact that potential differences between responders and non-responders could not be assessed. Another important limitation to this survey is that the self-reported answers regarding current practice might not reflect the actual practice. This survey is based on estimations of GPs themselves and no verification of data has been carried out. In addition, the prevalence of childhood morbid obesity seems to be relatively low in most practices (85.3% treats less than 5 patients), which might hamper statements regarding current practice and could cause recall bias. Furthermore, the sample size of 184 respondents did not meet the desired minimum of the sample size calculation due to a lower than anticipated response rate. Although this must be kept in mind when interpreting the results, the current sample is the largest to date investigating this topic.

Interpretation of results in relation to existing literature

The reported absence of CLI treatment in many cases and poor compliance to the national guidelines when defining treatment success implies that there is a relevant knowledge gap that may lead to inadequate treatment of paediatric morbid obesity in primary care. This implication is further supported by several comparable studies in adults, where a majority of GPs reported feeling unconfident, insufficiently competent, and disempowered regarding treatment of obese patients [17, 19,20,21]. One study surveying knowledge on procedural aspects, efficacy, and safety of adult bariatric surgical procedures in primary care practitioners found that non-referrers had significantly less knowledge compared to those who do refer [16]. Additionally, in a recent study 92.5% of family physicians reported that they would like to receive more education about bariatric surgery [21]. Educational resources on the topic of bariatric surgery must be provided to GPs, to improve care for morbidly obese adolescents.

Only few surveys that have investigated attitudes of GPs towards bariatric surgery in youngsters have been published. Claridge et al. performed a qualitative study among 12 GPs [20], while Penna et al. surveyed a variety of health care professionals (of which only 30 were GPs) [22]. Woolford et al. performed a survey comparable to the current design; however, their survey has been conducted in 2007 while this relatively new field of treatment options is evolving rapidly [23].

Interestingly, the study of Penna et al. revealed that GPs prompted a higher minimum age for bariatric surgery than surgeons. By contrast, GPs were less likely to prerequire parental counselling and parental involvement in the child’s weight management than surgeons. This discrepancy further supports the notion that education of GPs and communication between surgeons and GPs is necessary to offer a uniformly optimal quality of care for obese adolescents.

Conclusion

There may be a group of morbidly obese adolescents who would benefit from referral to bariatric surgery, but are instead treated sub-optimally. This could be the result of insufficient knowledge of clinical practice guidelines and bariatric surgery in general. Moreover, the fact that only half of the GPs would consider referral of selected adolescents, even though the majority considers bariatric surgery as an effective last-resort treatment option, may in part be based on opinions and matters of principle. These issues should be addressed by ameliorating communication and cooperation between surgeons and GPs as well as providing GPs with educational resources on bariatric surgery in adolescents and in general.

References

Visscher TL, Seidell JC (2001) The public health impact of obesity. Annu Rev Public Health 22:355–375

Llewellyn A, Simmonds M, Owen CG et al (2016) Childhood obesity as a predictor of morbidity in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 17(1):56–67

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD et al (2012) A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (London, England) 380(9859):2224–2260

Ahrens W, Pigeot I, Pohlabeln H et al (2014) Prevalence of overweight and obesity in European children below the age of 10. Int J Obes 38(Suppl 2):S99–S107

Schonbeck Y, Talma H, van Dommelen P et al (2011) Increase in prevalence of overweight in Dutch children and adolescents: a comparison of nationwide growth studies in 1980, 1997 and 2009. PLoS ONE 6(11):e27608

DCO (2010) Healthcare standard for obesity. Dutch Consortium of Obesity, Amsterdam

Barlow SE (2007) Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics 120(Suppl 4):S164–S192

Oude Luttikhuis H, Baur L, Jansen H et al (2009) Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):Cd001872

Peirson L, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Morrison K et al (2015) Treatment of overweight and obesity in children and youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ Open 3(1):E35–E46

Styne DM, Arslanian SA, Connor EL et al (2017) Pediatric obesity-assessment, treatment, and prevention: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102(3):709–757

Nobili V, Vajro P, Dezsofi A et al (2015) Indications and limitations of bariatric intervention in severely obese children and adolescents with and without nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: ESPGHAN hepatology committee position statement. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 60(4):550–561

National Clinical Guideline C. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance (2014) Obesity: identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in children, young people and adults: partial update of CG43. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK), London

Mathus-Vliegen L, Toouli J, Fried M et al (2012) World gastroenterology organisation global guidelines on obesity. J Clin Gastroenterol 46(7):555–561

Seídell JC, Beer AJ, Kuijpers T (2008) Richtlijn ‘diagnostiek en behandeling van obesitas bij volwassenen en kinderen’. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 152(38):2071–2076

Nederland PO (2010) Zorgstandaard Obesitas. November 2010 edn. Amsterdam 2010 Sep 20

Al-Namash H, Al-Najjar A, Kandary WA et al (2011) Factors affecting the referral of primary health care doctors toward bariatric surgery in morbid obesity. Alexandria J Med 47(1):73–78

Balduf LM, Farrell TM (2008) Attitudes, beliefs, and referral patterns of PCPs to bariatric surgeons. J Surg Res 144(1):49–58

Kim KK, Yeong LL, Caterson ID et al (2015) Analysis of factors influencing general practitioners’ decision to refer obese patients in Australia: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 16:45

Salinas GD, Glauser TA, Williamson JC et al (2011) Primary care physician attitudes and practice patterns in the management of obese adults: results from a national survey. Postgrad Med 123(5):214–219

Claridge R, Gray L, Stubbe M et al (2014) General practitioner opinion of weight management interventions in New Zealand. J Prim Health Care 6(3):212–220

Auspitz M, Cleghorn MC, Azin A et al (2016) Knowledge and perception of bariatric surgery among primary care physicians: a survey of family doctors in Ontario. Obes Surg 26(9):2022–2028

Penna M, Markar S, Hewes J et al (2014) Adolescent bariatric surgery—thoughts and perspectives from the UK. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11(1):573

Woolford SJ, Clark SJ, Gebremariam A et al (2010) To cut or not to cut: physicians’ perspectives on referring adolescents for bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 20(7):937–942

Bartlett JE, Kotrlik JW, Higgins CC (2001) Organizational research: determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Inf Technol Learn Perform J 19(1):43–50

Alvarenga ES, Lo Menzo E, Szomstein S et al (2016) Safety and efficacy of 1020 consecutive laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies performed as a primary treatment modality for morbid obesity. A single-center experience from the metabolic and bariatric surgical accreditation quality and improvement program. Surg Endosc 30(7):2673–2678

Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E et al (2014) Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (8):CD003641

Shoar S, Saber AA (2017) Long-term and midterm outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Surg Obes Relat Dis 13(2):170–180

Mehaffey JH, LaPar DJ, Clement KC et al (2016) 10-Year outcomes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann Surg 264(1):121–126

Obeid NR, Malick W, Concors SJ et al (2016) Long-term outcomes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10- to 13-year data. Surg Obes Relat Dis 12(1):11–20

Shoar S, Mahmoudzadeh H, Naderan M et al (2017) Long-term outcome of bariatric surgery in morbidly obese adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 950 patients with a minimum of 3 years follow-up. Obes Surg 27(12):3110–3117

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Appendix

Appendix

Survey: attitudes towards bariatric surgery in children and adolescents

-

1.

What is your current position?

-

a.

Registered General Practitioner (GP)

-

b.

General Practitioner in training (GPit)

-

a.

-

2.

How many years of experience do you have (including training)?

The next questions are asked to give us information about your experience and current practice regarding morbidly obese children (defined as BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 with obesity-associated comorbidity; sex and age adjusted). Below you can find the Dutch sex and age adjusted thresholds for morbid obesity.

Age | Boys | Girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

BMI 35 | BMI 40 | BMI 35 | BMI 40 | |

12 | 30.2 | 34.8 | 31.2 | 38.0 |

13 | 31.8 | 36.9 | 32.6 | 38.9 |

14 | 32.9 | 38.4 | 33.3 | 39.4 |

15 | 33.7 | 39.1 | 33.9 | 39.7 |

16 | 34.2 | 39.5 | 34.3 | 39.9 |

17 | 34.6 | 39.8 | 34.7 | 39.9 |

-

3.

How many morbidly obese children do you treat currently?

-

a.

<5

-

b.

5–15

-

c.

15–30

-

d.

>30

-

a.

-

4.

Which of the following treatment modalities or referrals do you offer to children with morbid obesity (never, seldom, sometimes, often, always)?

-

a.

Lifestyle advices

-

b.

Dietary advices (provided by dietician)

-

c.

Sports or exercise programs (provided by expert)

-

d.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (provided by behavioural therapist)

-

e.

Family treatment (provided by behavioural therapist)

-

f.

Multidisciplinary treatment programs

-

g.

Referral to pediatrician

-

h.

Other (please describe)

-

a.

-

5.

When do you consider the provided treatment as successful in full-grown morbidly obese children?

-

a.

Stabilization of weight after 6 months treatment

-

b.

Stabilization of weight after 12 months treatment

-

c.

Weight loss ≥5% after 12 months treatment

-

d.

Weight loss ≥10% after 12 months treatment

-

e.

Improvement of comorbidity, irrespective of weight changes

-

f.

Other (please describe)

-

a.

-

6.

In how many children with morbid obesity do you estimate that the provided therapy is effective?

-

a.

0–25%

-

b.

25–50%

-

c.

50–75%

-

d.

75–100%

-

a.

-

7.

Do you think that bariatric surgery can be an effective treatment modality in morbidly obese children who do not respond sufficiently to conservative treatment?

-

a.

Yes

-

b.

No

-

a.

-

8.

Would you consider referral of a child for bariatric surgery in case conservative treatment does not lead to sufficient improvement?

-

a.

Yes

-

b.

No (branching logic: respondent proceeds to question 14)

-

a.

The following questions will be about your attitude towards bariatric surgery in morbidly obese children. For all questions, a stable and supportive home situation can be assumed. In addition, it can be assumed that combined lifestyle interventions have been provided for at least 1 year without success.

-

9.

Should there be a minimum age threshold for childhood bariatric surgery?

-

a.

No, not necessary

-

b.

Yes, namely … (number in years)

-

a.

-

10.

In the case of no comorbidity, which BMI would you apply as a lower threshold when considering referral of a morbidly obese child for bariatric surgery?

-

a.

30 kg/m2

-

b.

35 kg/m2

-

c.

40 kg/m2

-

d.

50 kg/m2

-

e.

60 kg/m2

-

f.

Other (please describe)

-

a.

-

11.

Would the presence of comorbidity influence the answer given at question 10?

-

a.

Yes

-

b.

No (branching logic: respondent proceeds to question 13)

-

a.

-

12.

Presence of which of the following comorbidities would influence your attitude towards referral of morbidly obese children for bariatric surgery (as answered in question 10)?

-

a.

Type II diabetes mellitus

-

b.

Dyslipidemia

-

c.

Hypertension

-

d.

Obstructive sleep apnea

-

e.

Arthropathies

-

f.

Non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis

-

g.

Depressive disorder

-

h.

Other (please describe)

-

a.

-

13.

In your opinion, which of the following are reasons for reluctance in referring children for bariatric surgery?

-

a.

Uncertainty towards short-term complications

-

b.

Uncertainty towards long-term complications

-

c.

Uncertainty towards short-term efficacy

-

d.

Uncertainty towards long-term efficacy

-

e.

Weight loss programs are nearly always sufficient in case of a motivated patient

-

f.

Bariatric surgery is only treatment of symptoms, it does not address the cause of the disease

-

g.

None of the above

-

h.

Other (please describe)

-

a.

Survey completed for all respondents who answered ‘Yes’ at question 8.

-

14.

In your opinion, which of the following are reasons for reluctance/not referring children for bariatric surgery?

-

a.

Uncertainty towards short-term complications

-

b.

Uncertainty towards long-term complications

-

c.

Uncertainty towards short-term efficacy

-

d.

Uncertainty towards long-term efficacy

-

e.

Weight loss programs are nearly always sufficient in case of a motivated patient

-

f.

Bariatric surgery is only treatment of symptoms, it does not address the cause of the disease

-

g.

Other (please describe)

-

a.

-

15.

Are there specific situations in which you would consider childhood bariatric surgery after all?

-

a.

No

-

b.

Yes (please describe)

-

a.

Survey completed for all respondents who answered ‘No’ at question 8.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Roebroek, Y.G.M., Talib, A., Muris, J.W.M. et al. Hurdles to Take for Adequate Treatment of Morbidly Obese Children and Adolescents: Attitudes of General Practitioners Towards Conservative and Surgical Treatment of Paediatric Morbid Obesity. World J Surg 43, 1173–1181 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4874-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4874-5