Abstract

In a new prescribing qualification course for specialist oncology nurses, we thought that it is important to emphasize pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reaction (ADR) reporting. We aimed to develop and evaluate an ADR reporting assignment for specialist oncology nurses. The quality of report documentation was assessed with the “Clinical Documentation tool to assess Individual Case Safety Reports” (ClinDoc). The relevance of the reports was evaluated in terms of ADR seriousness, the listing for additional monitoring of the drug by European Medicines Agency (EMA), and lack of labelling information about the ADR. Nurses’ opinions of the assignment were evaluated using an E-survey. Thirty-three ADRs were reported, 32 (97%) of which were well documented according to ClinDoc. Thirteen ADRs (39%) were “serious” according to CIOMS criteria. In five cases (15%), the suspect drugs were listed for additional monitoring by EMA and in seven cases (21%), the ADR was not mentioned in the Summary of Product Characteristics. Twenty-five (78.1%) of the 32 enrolled nurses completed the E-survey. Most were > 45 years of age (68%), female (92%) and had extensive clinical experience (6–33 years). All agreed or completely agreed that the reporting assignment was useful, that it fitted in daily practice and that it increased their attention for medication/patient safety. A large majority (84.0%) agreed the assignment changed how they dealt with ADRs. Specialist oncology nurses are capable of reporting ADRs, and they considered the assignment useful. The assignment yielded valuable, relevant, and well-documented ADR reports for pharmacovigilance practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) by health professionals is a widely used method for ADR detection (Miguel et al. 2013). This is vital for identifying unknown, uncommon and serious ADRs, with a view to improving medication safety and understanding the risks of drugs (Molokhia et al. 2009; Sultana et al. 2013). However, this spontaneous reporting system is dependent on the responsiveness of health professionals and on the quality and quantity of their ADR reports. Reporting ADRs is typically the responsibility of physicians and is mandatory in some countries such as the Netherlands (Hazell and Shakir 2006; Lopez-Gonzalez et al. 2009; Molokhia et al. 2009). Nevertheless, underreporting remains a barrier to optimal ADR monitoring (Hazell and Shakir 2006; Lopez-Gonzalez et al. 2009; Molokhia et al. 2009). To stimulate ADR reporting, pharmacists, medical/pharmacy students, patients, and nurses are now authorized to report ADRs, which has the added advantage of obtaining information from other, non-physician sources (van Grootheest et al. 2003; Steurbaut and Hanssens 2014; van Eekeren et al. 2014; Harmark et al. 2015).

Nurses are a potentially valuable source of ADR reports, because they administer most drugs in hospitals and are often present when an ADR occurs (Hall et al. 1995). Furthermore, nurses report different types of suspected ADRs from those reported by physicians; for instance, they report more side effects after parenteral administration (Hall et al. 1995; Sacilotto et al. 1995; Ranganathan et al. 2003; Bigi and Bocci 2017). Although nurse reporting seems promising, it has been queried whether nurses are adequately prepared for this role. Previous studies have shown that they have little knowledge and poor practice regarding pharmacovigilance and the spontaneous reporting system (Hanafi et al. 2012; Hanrath 2016; Salk and Ehrenpreis 2016). Moreover, a recent literature review emphasized the need for pharmacovigilance training in (postgraduate) nurse education (Bigi and Bocci 2017).

When we developed a new prescribing qualification course for specialist oncology nurses, we wanted to focus attention on their role in drug safety. Although this prescribing qualification allows nurses to prescribe a limited set of drugs, their role in pharmacovigilance would cover the entire field of oncology, with its multiple drugs, many of which give rise to serious ADRs. It is unclear how to best prepare (specialist) nurses for this task. Some interventions have been shown to be effective for qualified physicians, but few studies have investigated other health professionals receiving further training (Pagotto et al. 2013). While passive educational methods (e.g. lectures) are typically used during training (Rosebraugh et al. 2003; Durrieu et al. 2007), those being taught prefer active learning forms (Elkalmi et al. 2011; Gavaza and Bui 2012; Schutte et al. 2017c). Such active learning approaches are preferential for adult learners (Yardley et al. 2012). By combining the preference for an active learning approach and our experience with a student ADR-reporting assignment (van Eekeren et al. 2014; van Eekeren and Schutte 2015), we hypothesized that an ADR reporting assignment would be a suitable approach for training the pharmacovigilance skills of specialist oncology nurses.

Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to establish the value of an ADR reporting assignment to pharmacovigilance centres and specialist nurses following a prescribing training course. A secondary objective was to evaluate the preparedness of these specialist nurses for their role in pharmacovigilance, their intention/attitudes and skills/ towards pharmacovigilance and ADR reporting.

Methods

Setting

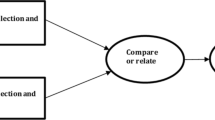

The Amstel Academy (VU University Medical Center) offers registered specialist oncology nurses a course on prescribing to enable them to qualify to prescribe a limited set of frequently prescribed drugs (anti-diarrhoea drugs, anti-emetics, analgesics (non-opioids) and benzodiazepines). Nurses follow the course in addition to their work in different (most non-academic) hospitals in the Netherlands. The course consists of 4 days (6 h/day) spread over half a year, completed by a prescribing assessment. The module overview is displayed in Fig. 1. It covers pharmacovigilance by means of a lecture on pharmacovigilance and a practical ADR reporting assignment. The reporting assignment was introduced during a pharmacovigilance lecture, in which the nurses were instructed to report an ADR that was either unknown, exceptional or unexpected to them. The assignment was followed by a group discussion of the ADRs reported, led by a pharmacotherapy teacher (T.S.) and assessor from the Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb (R.vE.).

Overview of the first course on prescribing at the Amstel Academy (VU University Medical Center) for specialist oncology nurses between November 2015 and May 2016. The nurses follow the course in addition to their work in different (most non-academic) hospitals in the Netherlands which is depicted in the white boxes. The course consists of 4 days (6 h/day) equally spread over half a year, which is depicted as black boxes. Within these boxes, the discussed themes are noted. The nurses were instructed regarding the reporting assignment during a lecture in day 2 (January). This lecture included a general lecture on pharmacovigilance in the Netherlands. The ADRs had to be reported before the group discussion (day 4, in March). Following the last day of the module, the evaluation survey was distributed

Population

Thirty-two specialist oncology nurses enrolled for this course in November 2015 in two separate groups. All were invited to voluntarily participate in this study and complete an anonymous E-questionnaire after the course. Based on previous E-questionnaire studies, we expected a response rate of 25–50%.

Instruments

Two aspects of the course were evaluated. First, the quality of documentation and relevance of the ADRs reported and second, the nurses’ perspective of the reporting assignment together with their current attitudes and skills regarding pharmacovigilance and ADR reporting.

The quality of documentation of the reported ADRs was measured by an assessor from the Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb, using the novel “Clinical Documentation tool to assess Individual Case Safety Reports” (ClinDoc). The ClinDoc tool was previously described by Rolfes and provides a completeness score (0–100%) (Rolfes et al. 2016a; Oosterhuis et al. 2016; Rolfes et al. 2016b; Rolfes et al. 2017). It assesses the relevance of the information provided in an ADR report (e.g. information on the ADR, time relationship, drug, and patient characteristics). The ClinDoc is displayed in Table 1.

The relevance of the reported ADR was assessed with respect to label information for the suspect drug (in Summary of Product Characteristics), seriousness of the ADR (According to CIOMS criteria 1999), additional monitoring of the drug, off-label use of the drug and severity of the ADR as a reason to stop necessary treatment. The nurses were not informed that their reports would be assessed for completeness.

The nurses’ perspective was evaluated with an E-questionnaire covering three themes (intention/attitudes, knowledge/skills and evaluation of pharmacovigilance teaching) in 13 questions. Participants were sent an information letter and returned an informed consent statement before they completed the questionnaire. They also provided information about baseline characteristics, including their earlier ADR reporting experience and whether ADR reporting was covered in their initial training as nurse. In the E-questionnaire, once a question was answered, it was not possible for respondents to return to earlier answers (since some questions consisted of the answers to earlier questions). There was no time limit for E-questionnaire completion, but on the basis of a pilot study, we estimated that it would take 8–10 min to complete. The first two themes intention/attitudes and knowledge/skills regarding pharmacovigilance and ADR reporting were investigated using a set of open-ended question and dichotomous questions that were used in earlier studies (Schutte et al. 2017c; Schutte et al. 2017d). The third theme was an evaluation of the ADR-reporting assignment and (previous) pharmacovigilance teaching. This theme consisted of the open question “what have you learned?” and 18 statements that covered participants’ opinions of the ADR-reporting assignment, discussion of the ADR-reporting assignment, their current and past education in pharmacovigilance and whether they considered this education sufficient and appropriate for future clinical practice. Answers were scored on a Likert scale (5- or 7-point). The complete questionnaire is displayed in Appendix 1.

Data analysis

All data were imported in SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM Corp.; Armonk, New York). Descriptive statistics were used to report frequencies and means/standard deviations (SD) of survey results. Open questions were analysed using content/thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006). The mean composite knowledge score was calculated as the sum of the correct answers divided by the number of questions answered (uncorrected for guessing). Skills were analysed as two separate outcomes (i.e. knowing where to report and knowing what to report). A significance level with an alpha of 5% was considered statistically significant (p < 0.05) in all analyses.

Results

All 32 oncology nurses enrolled in the prescribing qualification course were invited to participate in this study by e-mail; 25 completed the questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 78.1%. Of the responders, 23 were female (92%), 22 (68%) were 45 years or older and their clinical experience as nurse ranged between 6 and 33 years. While 19 nurses (76%) reported that their initial training curriculum covered ADRs, only 2 nurses (8%) indicated that the curricula covered the reporting of ADRs. Before they enrolled, 7 nurses (28%) had reported one or more ADRs to the Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb.

Quality and relevance of reports

A total of 33 Individual Case Safety Reports (ICSRs) were reported during the assignment, accounting for 41 ADRs. In 23 (70%) of the ICSRs, the suspect drug was a cytostatic agent, used in the treatment of malignant diseases. Gastrointestinal disorders and skin reactions were the most frequently reported ADRs. Overall, 32 (97%) of the reports were well documented. Most ICSRs were considered relevant, in terms of seriousness (according to CIOMS) of the ADR (n = 13, 39%), lack of label information about the reported ADR (n = 7, 21%), additional monitoring of the suspect drug by EMA (European Medicine Agency; n = 4, 12%), the ADR being the cause of withdrawal of a cytostatic drug (n = 4, 12%) and off-label use of the suspect drug (n = 2, 6%). Eleven (33%) reports used hospitalization as criterion of ADR seriousness, one used a life-threatening situation and one used death. Further details regarding ICSRs, ClinDoc score and relevance are displayed in Table 2 and Appendix 1.

The ADR-reporting assignment and pharmacovigilance teaching

The 25 participants agreed that the reporting assignment was useful, that it was consistent with their daily work and duties and that it made them more aware of medication and patient safety. Only nine participants (36.0%) thought that the reporting assignment cost a lot of time. Twenty-one participants (84.0%) agreed that the reporting assignment changed how they dealt with ADRs. The results of the participant evaluation are displayed in Fig. 2.

Intention/attitudes

After participation, all the nurses reported they intended to report serious and unknown ADRs, because reporting them “contributed to medication safety” and “improved patient safety”. They also considered that it was “personally beneficial” and “educated others about drug risks”. The nurses did not consider that reporting ADRs would “break trust with patients” or that it would “increase the risk of malpractice”. The nurses’ attitudes towards ADR reporting in different situations are displayed in Table 3.

Knowledge and skills

After the reporting assignment, all 25 nurses who returned the questionnaire said they knew where to report ADRs, and all but one (96%) knew what information was needed to fill in an ADR report. The mean score for the 12 knowledge questions was 75% (SD 13). The results for the individual questions are displayed in Table 4. Analysis of the open-ended questions showed that nurses considered that they had learned why it is important to be aware of ADRs and how to recognize them, that they had experienced and learned how and what to report and that they had learned more about the Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb and its role in assessing ADRs, in providing feedback, and as knowledge centre for drug safety (Table 4).

Discussion

Specialist oncology nurses are capable of reporting ADRs, as evidenced by their good clinical documentation of the ICSRs and by the relevance of their reports. The reporting assignment yielded valuable, relevant and well-documented ADR reports for pharmacovigilance. The nurses were ready for their role in pharmacovigilance practice, had positive attitudes/intentions and had adequate skills/knowledge about pharmacovigilance and ADR reporting after they had completed the prescribing qualification course.

The value of ADR reports made by health professionals receiving further training has not been studied earlier with a validated instrument. An earlier study of nurses reported that only 48% (95% CI 42.4–53.7) of ADR forms were complete in all relevant aspects (Ranganathan et al. 2003). Furthermore, healthcare professionals scored a mean of 78% on the ClinDoc instruments’ pilot study (Rolfes et al. 2016b). The levels of completeness of both referenced studies are considerably lower compared to the mean 89% ClinDoc score in the present study. The high scores for clinical documentation of the ICSRs in the present study show that specialist oncology nurses are highly capable of providing relevant and appropriate information in their ADR reports, even in a training situation.

Most of the reported ADRs were very relevant for pharmacovigilance, most frequently because the ADR was serious or the suspect drug was listed by EMA for additional monitoring. In 39% of the ICSRs, the ADR was serious according to CIOMS criteria, a significantly higher percentage than reported in three earlier studies of ADR reporting by nurses. In a study by Ranganatan, nurses reported a higher proportion of serious suspected ADRs than general practitioners and hospital physicians (13.5 versus 12.9 and 9.1%, respectively) (Ranganathan et al. 2003). The opposite was found in a French study in 1995, which found that doctors reported more (suspected) serious ADRs than nurses (19 versus 10%, respectively) (Sacilotto et al. 1995). In a previous study in the Netherlands, 25% of ADRs reported by health professional were considered serious (Rolfes et al. 2015). The higher number of serious ADRs in our present study is probably due to the high frequency of severe and serious ADRs to the cytostatic agents used in oncology. Although specialist oncology nurses are only permitted to prescribe a small set of supportive drugs, they apparently felt responsible for reporting ADRs to the cytostatic agents themselves.

The specialist oncology nurses had positive attitudes/intentions and adequate skills/knowledge about pharmacovigilance and ADR reporting. Almost all nurses intended to report serious ADRs in the future (mean 6.6 SD 0.6). The specialist oncology nurses had higher scores in this respect than medical students (mean 6.2; SD 1.0) (Schutte et al. 2017c), pharmacists (mean 5.2; SD 1.5) (Gavaza et al. 2011) and pharmacy students (mean 5.9; SD 1.5) (Gavaza and Bui 2012), who were all assessed with the same questionnaire. These results are possibly related to the nurses’ expectations regarding the relevance, benefits and costs of reporting. Although the nurses expected reporting to be somewhat time consuming (mean 4.5 SD 1.6 on 7-point Likert scale), pharmacists thought that it would be more time consuming (mean 5.1 SD 1.6) (Gavaza et al. 2011). More nurses than pharmacists considered that reporting is “personally beneficial” (mean 6.2 SD 0.6 versus mean 5.0 SD 1.6, respectively) (Gavaza et al. 2011). Furthermore, their skills and knowledge in pharmacovigilance were considerably better than those of final-year medical students in the Netherlands (scores of 75 versus 68% for basic pharmacovigilance knowledge, respectively) (Schutte et al. 2017c). All but one of the nurses knew where and what was necessary to report for a good ADR report. This was far better than final-year medical students, of whom 78% knew where they should report an ADR and 33% knew what was necessary for a good ADR report. The ADR-reporting assignment and plenary discussion were considered useful by the nurses, and they commented that it changed how they dealt with ADRs. All these findings are important as they potentially influence the willingness and likelihood of these nurses reporting serious ADRs in the future.

The main limitation of this study is its relative small sample size and design—there was no pre-participation measurement or control group. Moreover, the population mainly consisted of experienced female nurses. Furthermore, the educational setting might have biased results, since the nurses may have put more effort into the assignment than they would do in their usual workplace settings. Taken these limitations into account, this study showed the value of an ADR reporting assignment, as it offered oncology nurses valuable experience and training while providing valuable and relevant ADR reports for pharmacovigilance. Earlier studies have demonstrated comparable positive outcomes of giving learners legitimate roles in real (pharmacotherapy) problems of real patients (Dekker et al. 2015; Schutte et al. 2017a; Schutte et al. 2017b).

Given the positive results of the ADR reporting assignment in this population, future research should focus on optimization of pharmacovigilance education for health professionals, especially assignments that are grounded in real practice. Such research should study the long-term effects of educational interventions and whether less experienced health professionals are also capable of contributing to pharmacovigilance while performing practical assignments in real practice, as we demonstrated in this study. To conclude, the adverse drug reaction reporting assignment yielded valuable, relevant and well-documented ADR reports for pharmacovigilance. In addition, this assignment was considered educational by the specialist oncology nurses. The participating nurses had positive attitudes/intentions and had adequate skills/knowledge about pharmacovigilance and ADR reporting after they had completed the prescribing qualification course.

References

Bigi C, Bocci G (2017) The key role of clinical and community health nurses in pharmacovigilance. Eur J Clin Pharmacol

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101

Counsel for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) (1999) Reporting adverse drug reactions; definitions of terms and criteria for their use. http://www.cioms.ch/publications/reporting_adverse_drug.pdf

Dekker RS, Schutte T, Tichelaar J, Thijs A, van Agtmael MA, de Vries TP, Richir MC (2015) A novel approach to teaching pharmacotherapeutics—feasibility of the learner-centered student-run clinic. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 71:1381–1387

Durrieu G, Hurault C, Bongard V, Damase-Michel C, Montastruc JL (2007) Perception of risk of adverse drug reactions by medical students: influence of a 1 year pharmacological course. Br J Clin Pharmacol 64:233–236

Elkalmi RM, Hassali MA, Ibrahim MI, Widodo RT, Efan QM, Hadi MA (2011) Pharmacy students’ knowledge and perceptions about pharmacovigilance in Malaysian public universities. Am J Pharm Educ 75:96

Gavaza P, Brown CM, Lawson KA, Rascati KL, Wilson JP, Steinhardt M (2011) Influence of attitudes on pharmacists’ intention to report serious adverse drug events to the Food and Drug Administration. Br J Clin Pharmacol 72:143–152

Gavaza P, Bui B (2012) Pharmacy students’ attitudes toward reporting serious adverse drug events. Am J Pharm Educ 76:194

Hall M, McCormack P, Arthurs N, Feely J (1995) The spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions by nurses. Br J Clin Pharmacol 40:173–175

Hanafi S, Torkamandi H, Hayatshahi A, Gholami K, Javadi M (2012) Knowledge, attitudes and practice of nurse regarding adverse drug reaction reporting. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 17:21–25

Hanrath C (2016) Bijwerkingen melden—daar wordt iedereen beter van. Nursing: 3

Harmark L, van HF, Grundmark B (2015) ADR reporting by the general public: lessons learnt from the Dutch and Swedish systems. Drug Saf 38:337–347

Hazell L, Shakir SA (2006) Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. Drug Saf 29:385–396

Lopez-Gonzalez E, Herdeiro MT, Figueiras A (2009) Determinants of under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. Drug Saf 32:19–31

Miguel A, Azevedo LF, Lopes F, Freitas A, Pereira AC (2013) Methodologies for the detection of adverse drug reactions: comparison of hospital databases, chart review and spontaneous reporting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 22:98–102

Molokhia M, Tanna S, Bell D (2009) Improving reporting of adverse drug reactions: systematic review. Clin Epidemiol 1:75–92

Oosterhuis I, Rolfes L, Ekhart C, Muller-Hansma A, Härmark L (2016) Development and validity testing of a clinical documentation-tool to assess individual case safety reports in an international setting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 25:417

Pagotto C, Varallo F, Mastroianni P (2013) Impact of educational interventions on adverse drug events reporting. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 29:410–417

Ranganathan SS, Houghton JE, Davies DP, Routledge PA (2003) The involvement of nurses in reporting suspected adverse drug reactions: experience with the meningococcal vaccination scheme. Br J Clin Pharmacol 56:658–663

Rolfes L, Oosterhuis I, Ekhart C, Muller-Hansma A, Härmark L (2016a) Development and validity testing of a clinical documentation-tool to assess individual case safety reports in an international setting. International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management, The Convention Centre Dublin, Dublin, Ireland. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 25(Supp S3):417

Rolfes L, van der Linden L, van Hunsel F, Taxis K, van Puijenbroek EP (2016b) The documentation of clinical information of adverse drug reaction reports: a paired comparison of ‘duplicate’ reports of patients and healthcare professionals. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 25:418–419

Rolfes L, van Hunsel F, van der Linden L, Taxis K, van Puijenbroek E (2017) The quality of clinical information in adverse drug reaction reports by patients and healthcare professionals: a retrospective comparative analysis. Drug Saf 40:607–614

Rolfes L, van Hunsel F, Wilkes S, van Grootheest K, van Puijenbroek E (2015) Adverse drug reaction reports of patients and healthcare professionals-differences in reported information. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 24:152–158

Rosebraugh CJ, Tsong Y, Zhou F, Chen M, Mackey AC, Flowers C, Toyer D, Flockhart DA, Honig PK (2003) Improving the quality of adverse drug reaction reporting by 4th-year medical students. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 12:97–101

Sacilotto K, Bagheri H, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc JL, Montastruc P (1995) Adverse drug effect notifications by nurses and comparison with cases reported by physicians. Therapie 50:455–458

Salk A, Ehrenpreis ED (2016) Attitudes and usage of the Food and Drug Administration adverse event reporting system among gastroenterology nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Gastroenterol Nurs 39:25–31

Schutte T, Prince K, Richir M, Donker E, van Gastel L, Bastiaans F, de Vries H, Tichelaar J, van Agtmael M (2017a) Opportunities for students to prescribe: an evaluation of 185 consultations in the student-run cardiovascular risk management Programme. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.12904

Schutte T, Tichelaar J, Dekker RS, Thijs A, de Vries TP, Kusurkar RA, Richir MC, van Agtmael MA (2017b) Motivation and competence of participants in a learner-centered student-run clinic: an exploratory pilot study. BMC Med Educ 17:23

Schutte T, Tichelaar J, Reumerman MO, van Eekeren R, Rissmann R, Kramers C, Richir MC, van Puijenbroek EP, van Agtmael MA, Education Committee/Working Group Research in Education of the Dutch Society of Clinical P, Biopharmacy UTN (2017c) Pharmacovigilance skills, knowledge and attitudes in our future doctors—a nationwide study in the Netherlands. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 120:475–481

Schutte T, Tichelaar J, Reumerman MO, van Eekeren R, Rolfes L, van Puijenbroek EP, Richir MC, van Agtmael MA (2017d) Feasibility and educational value of a student-run pharmacovigilance programme: a prospective cohort study. Drug Saf 40:409–418

Steurbaut S, Hanssens Y (2014) Pharmacovigilance: empowering healthcare professionals and patients. Int J Clin Pharm 36:859–862

Sultana J, Cutroneo P, Trifiro G (2013) Clinical and economic burden of adverse drug reactions. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 4:S73–S77

van Eekeren R, Schutte T (2015) Netherlands national education programme. Uppsala reports 70:18–18

van Eekeren R, van der Horst P, Hut F, van Grootheest K (2014) Leer studenten bijwerkingen herkennen. Medisch Contact:150–154

van Grootheest K, de Graaf L, de Jong-van den Berg L (2003) Consumer adverse drug reaction reporting: a new step in pharmacovigilance? Drug Saf 26:211–217

WEB-RADR (2017) WEB-RADR: Recognising Adverse Drug Reactions, Work package 4; https://web-radr.eu/

Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T (2012) Experiential learning: AMEE guide no. 63. Med Teach 34:e102–e115

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participating oncology nurses for their enthusiasm and willingness to evaluate the reporting assignment, Michael Reumerman (VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam) for his earlier contributions to the used questionnaires, Leàn Rolfes (Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb, Den Bosch) for sharing and allowing us to use the ClinDoc tool and Tim Smeets (Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, now Erasmus MC, Rotterdam), who assessed reported ADRs.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the work, drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors provided final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study did not fall under the scope of the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act. Participation was voluntary, anonymous and based on informed consent. Participants did not receive credit or other incentives to participate. The ethics review board of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO) approved this research (ID: 692).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 57 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Schutte, T., van Eekeren, R., Richir, M. et al. The adverse drug reaction reporting assignment for specialist oncology nurses: a preliminary evaluation of quality, relevance and educational value in a prospective cohort study. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol 391, 17–26 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-017-1430-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-017-1430-z