Abstract

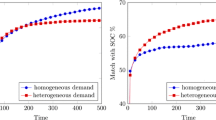

Positional behaviour is arguably a source of social externalities. Remedies for this market failure are defended by some authors and rejected by others. One of the issues discussed is the role that the competition for positional goods may have in generating technological innovation. This article aims to contribute to the understanding of the dynamics of this process through the use of an agent-based model. Simulations show a plausible dynamics of the process of technological innovation as generated by consumption of positional nature. An interpretation of the results in the scope of the policy discussion in question is provided. The influence of key factors such as income inequality, the materialization of the Hirsch conjecture, and characteristics of the network of relative preferences, is analised. We also frame the potential interest of positional consumption and this model in particular in the context of the ongoing discussion among evolutionary economists on the behaviour of demand.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Literature on positional consumption commonly uses the term to refer simply to consumption where satisfaction is defined by social scarcity. Our work also adopts the nomenclature in this stricter sense.

Authors like Layard (1980), Ng (1987) and others suggested income taxation to bring the balance of private and public expenditure to a level consistent with welfare objectives. Before Hirsch, Duesenberry (1949, pp 92–104) suggested the need for intervention in an economic system with interdependent consumer preferences, particularly through progressive income taxation.

In fact, this type of non-linearity was possibly responsible for the neglect of economics research on the theory of consumer relative preferences. 1949) proposed a credited theory of consumer behaviour which took into account relative preferences. However, it soon became marginalized from mainstream analyses. Possibly, the mathematization of the economics discipline at the time rendered the consideration of relative preferences as undesirable from the point of view of the tractability of problems (Mason 2000).

Versions of the good under study are further simply designated as goods.

k p = 20 in all simulations below.

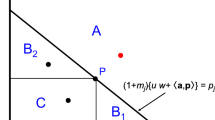

For the purposes of this work, a ranking characterizes the hierarchical order of subjects before a given attribute. The ranking is a sequence of integers between one (1) and the number of subjects characterized by the ranking (C). Rankings are attributed by decreasing order of the attribute values of subjects. In this case, the subjects are the consumers and the attribute is their income.

A k of 2 is equivalent to a Gini index of 0.251 or a Hoover index of 0.219.

In terms of formal model implementation, this was done simply by doubling the number of iterations and reducing to half the average income \(\overline {W}\) in each period.

References

Aversi R, Dosi G, Fagiolo G, Meacci M, Olivetti C (1999) Demand dynamics with socially evolving preferences. Ind Corp Chang 8(2):353–408

Axelrod R, Tesfatsion L (2006) A guide for newcomers to agent-based modeling in the social sciences. In: Tesfatsion L, Judd KL (eds) Handbook of computational economics, vol 2, Appendix, 1st edn. Elsevier, North-Holland, pp 1647–1659

Dawid H (2006) Agent-based models of innovation and technological change. Handb Comput Econ 2:1235–1272

Dosi G (1988) Sources, procedures, and microeconomic effects of innovation. J Econ Lit 26(3):1120–1171

Dusenberry JS (1949) Income, saving, and the theory of consumer behavior. Oxford University Press, New York (1967)

Easterlin RA (1974) Does economic growth improve the human lot? In: David PA, Reder MW (eds) Nations and households in economic growth: essays in honour of Moses Abramovitz. Academic Press, Inc, New York

Frank RH (1999) Luxury fever. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Frank RH (2003) Are positional externalities different from other externalities? Draft for presentation at The Brookings Institution

Frank RH (2005) Positional externalities cause large and preventable welfare losses. Am Econ Rev Am Econ Assoc 95(2):137–141

Frank RH (2006) Taking libertarian concerns seriously: reply to Kashdan and Klein. Econ J Watch 3(3):435–451

Freeman C (1998) The economics of technical change. Trade, Growth and Technical Change, Cambridge, pp 16–54

Galbraith JK (1958) The Affluent Society, 40th Anniversary edn. Mariner Books, New York

Gershuny J (1983) Technical change and ‘social limits’. In: Ellis A, Kumar K (eds) Dilemmas of liberal democracies: studies in Fred Hirsch’s social limits to growth. Tavistock Publications, New York, pp 23–44

Hayek FA (1960) The constitution of liberty. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Hirsch F (1976) Social limits to growth. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Kashdan A, Klein DB (2006) Assume the positional: comment on Robert Frank. Econ J Watch 3(3):412–434

Layard R (1980) Human satisfactions and public policy. The Econ J 90(363):737–750

Levine AS, Frank RH, Dijk O (2010) Expenditure cascades. SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1690612. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1690612. Accessed 16 Feb 2013

Mason R (2000) The social significance of consumption: James Duesenberry’s contribution to consumer theory. J Econ Issues XXXIV(3):553–572

Metcalfe JS (2001) Consumption, preferences, and the evolutionary agenda. J Evol Econ 11(1):37–58

Nelson JI (2007) The sociology of consumer behavior. In: Bryant CD, Peck DL (eds) 21st century sociology. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks

Nelson RR, Consoli D (2010) An evolutionary theory of household consumption behavior. J Evol Econ 20(5):665–687

Nelson RR, Winter SG (1982) An evolutionary theory of economic change. Belknap Press, Cambridge

Ng YK (1987) Relative-income effects and the appropriate level of public expenditure. Oxf Econ Pap 39(2):293–300

Reinstaller A, Sanditov B (2005) Social structure and consumption: on the diffusion of consumer good innovation. J Evol Econ 15(5):505–531

Shermer M (2008) The mind of the market: compassionate apes, competitive humans and other tales from evolutionary economics. Times Books, New York

Swann P (2002) There’s more to economics of consumption than (almost) unconstrained utility maximization. In: McMeekin A (ed) Innovation by the demand. Manchester University Press, Manchester, pp 23–41

Valente M (2012) Evolutionary demand: a model for boundedly rational consumers. J Evol Econ 22(5):1029–1080

Veblen T (1899) The theory of the leisure class. Penguin Books (Ed. 1994), New York

Wilhite A (2006) Economic activity on fixed networks. Handb Comput Econ 2:1013–1045

Witt U (2001) Learning to consume—a theory of wants and the growth of demand. J Evol Econ 11(1):23–36

Witt U (2010) Symbolic consumption and the social construction of product characteristics. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 21(1):17–25

Zweimüller J (2000) Schumpeterian entrepreneurs meet Engel’s Law: the impact of inequality on innovation-driven growth. J Econ Growth 5(2):185–206

Acknowledgments

This work has benefited from partial financial support from the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia-FCT, under the 13 Multi-annual Funding Project of UECE, ISEG, Technical University of Lisbon.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bernardino, J.P.R., Araújo, T. On positional consumption and technological innovation: an agent-based model. J Evol Econ 23, 1047–1071 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-013-0317-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-013-0317-5

Keywords

- Positional consumption

- Relative preferences

- Innovation

- Agent-based modelling

- Demand behaviour

- Evolutionary economics

- Economic inequality

- Hirsch conjecture

- Social network effects