Abstract

Despite anecdotal evidence that recessions affect marriage and divorce rates, researchers do not agree about the direction and magnitude of the relationship. This paper reexamines the effect of business cycles on flows into and out of marriage, finding that increased unemployment rates are associated with reductions in both outcomes. The results are robust to the use of alternative measures of economic conditions, hold for both blacks and whites, and are concentrated among working-age individuals. Lag specifications and impulse response functions suggest that the effect of an unemployment shock on marriage is permanent, while the effect on divorce is temporary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“In U.S., Proportion Married at Lowest Recorded Levels.” Population Reference Bureau. September 2010. Data are from the U.S. Census Bureau, 2000 Census and American Community Survey.

National Vital Statistics Reports from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Bureau of Labor Statistics

See, for example, “Saying No to ‘I Do’ With the Economy in Mind,” in The New York Times (September 28, 2010) and “Can the Recession Save Marriage?” in The Wall Street Journal (December 11, 2009).

See, e.g., Roberts (2009)

I use an unbalanced panel, dropping state-years in which the relevant dependent variable is missing. Marriage data are missing for Louisiana in 2006 and Oklahoma in 2001–2003. Divorce data are missing for the following state-years: California: 1991–2009, Colorado: 1995–2000, Georgia: 2004–2009, Hawaii: 2003–2009, Indiana: 1991–2009, Louisiana: 1991–2001 and 2004–2009, Minnesota: 2005-2009, and Oklahoma: 2001–2003.

This tabulation is from the vital statistics micro-data, for the period 1978–1995.

The fact that my results are robust to the inclusion of controls for state-level demographic composition and remain largely unchanged when the regressions are run without weights is reassuring. I also obtain similar estimates when I run the main regression specification using marriage and divorce rates constructed using state total population estimates from the NCHS Cancer-SEER, which are adjusted population predictions based on the decennial census.

As this may give disproportionate weight to large states, I also run regressions unweighted, which allows each state an equal weight. Unweighted regressions produce results that are very similar in magnitude and significance to the weighted results.

Author’s calculation. Marriage (divorce) calculation based on approximate US single (married) female population in 2007.

Approximately 1.5 to 2.5 % for marriages, 0.8 to 1.3 % for divorces.

Note also that if reverse correlation were a significant source of bias, I would expect it to yield a negative correlation between marriage rates and employment to population ratios. However, as shown in Table 3, replacing unemployment rates with employment to population ratios yields positive coefficients in both marriage and divorce regressions.

Micro-level data on marriages is available for 46 states. Micro-level data on divorces is available for 32 states.

Because the denominators of marriage and divorce rates are defined using the number of females in each group, I use age and race of the female listed in each vital statistics entry to create these groups-specific counts of events.

Because the sample sizes in the CPS are relatively small, these group-specific unemployment rates are likely to be measured with a larger degree of error than general unemployment rates. To account for this, I weight these estimates by group-specific population. However, differential measurement error in group-specific unemployment rates is a potential source of bias, so these results should be interpreted with caution.

In 2009, according to totaldivorce.com, nine U.S. states had divorce waiting periods at least 12 months in length: Arkansas, Connecticut, Maryland, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, South Carolina, and West Virginia.

For a more thorough explanation of the local projection technique and evidence demonstrating both the consistency and the efficiency of local projections, see (Jordà (2005).

To allow for comparisons between the lag specification results and the impulse response function results, I run the lag specification using the 1978–1991 sample. The results are very similar to those shown in Fig. 3.

References

Amato P, Beattie B (2011) Does the unemployment rate affect the divorce rate: an analysis of state data 1960–2005. Soc Sci Res 40(3):704–715

Becker GS (1973) A theory of marriage: part I. J Polit Econ 81(4):813–846

Becker GS, Landes EM, Michael RT (1977) An economic analysis of marital instability. J Polit Econ 85(6):1141–1187

Bitler MP, Gelbach JB, Hoynes HW, Zavodny M (2004) The impact of welfare reform on marriage and divorce. Demography 41(2):213–236

Blau FD, Kahn LM, Waldfogel J (2000) Understanding young women’s marriage decisions: the role of labor and marriage market conditions. Ind Labor Relat Rev 53(4):624–647

Bougheas S, Georgellis Y (1999) The effect of divorce costs on marriage formation and dissolution. J Popul Econ 12(3):489–498

Brien MJ (1997) Racial differences in marriage and the role of marriage markets. J Hum Resour 32(4):741–778

Charles KK, Stephens M Jr (2004) Job displacement, disability, and divorce. J Labor Econ 22(2):489–522

Chiappori PA, Weiss Y (2001) Marriage contracts and divorce: an equilibrium analysis. Working Paper

Clark KB, Summers LH (1981) Demographic differences in cyclical employment variation. J Hum Resour 16(1):61–79

Dehejia R, Lleras-Muney A (2004) Booms, busts, and babies’ health. Q J Econ 119(3):1091–1130

Doiron D, Mendolia S (2012) The impact of job loss on family dissolution. J Popul Econ 25(1):367–398

Eliason M (2011) Lost jobs, broken marriages. J Popul Econ. doi:10.1007/s00148-011-0394-4

Elsby M, Hzobijn B, Sahin A (2008) Unemployment dynamics in the OECD. NBER Working Paper No. 14617

Elsby M, Hobijn B, Sahin A (2010) The labor market in the great recession. NBER Working Paper No. 15979

Ermisch JF, Francesconi M (2001) Family structure and children’s achievements. J Popul Econ 14(2):249–270

Fischer T, Liefbroer AC (2006) For richer, for poorer: the impact of macroeconomic conditions on union dissolution rates in the Netherlands 1972–1996. Eur Sociol Rev 22(5):519–532

Friedberg L (1998) Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? Evidence from panel data. Am Econ Rev 88(3):608–627

Gallo WT, Bradley EH, Siegel M, Kasl SV (2000) Health effects of involuntary job loss among older workers. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 55(3):S131–S140

Gutiérrez-Domènech M (2008) The impact of the labour market on the timing of marriage and births in Spain. J Popul Econ 21(1):83–110

Hellerstein JK, Morrill MS (2011) Booms, busts, and divorce. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, Vol. 11: Iss. 1 (Contributions), Article 54

Hess GD (2004) Marriage and consumption insurance: what’s love got to do with it? J Polit Econ 112(2):290–318

Hoynes HW (2000) The employment, earnings, and encome of less skilled workers over the business cycle. In: Card DE, Blank RM (eds) Finding jobs: work and welfare reform. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp 23–71

Hoynes HW, Miller DL, Schaller J (2012) Who suffers in recessions and jobless recoveries? Working Paper

Jensen P, Smith N (1990) Unemployment and marital dissolution. J Popul Econ 3(3):215–229

Jordà O (2005) Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections. Am Econ Rev 95(1):161–182

Kirk D, Thomas DS (1960) The influence of business cycles on marriage and birth rates. In: Roberts GB (ed) Universities-National Bureau Committee for Economic Research Demographic and economic change in developed countries. NBER Books 257–276

Klerman KA, Haider SJ (2004) A stock-flow analysis of the welfare caseload. J Hum Resour 29(4):865–886

Kondo A (2012) Gender-specific labor market conditions and family formation. J Popul Econ 25(1):151–174

Lichter DT, McLaughlin DK, Ribar DC (2002) Economic restructuring and the retreat from marriage. Soc Sci Res 31(2):230–256

Lindo, J (2011) Parental job loss and infant health. J Health Econ 30(5):869–879

Ogburn WF, Thomas DS (1922) The influence of the business cycle on certain social conditions. J Am Stat Assoc 18:324–340

Page ME, Stevens AH (2004) The economic consequence of absent parents. J Hum Resour 39(1):80–107

Rasul I (2006) Marriage markets and divorce laws. J Law Econ Organ 22(1):30–69

Roberts A (2009) Marriage and the great recession. In: Wilcox WB (ed) The state of our unions: the national marriage project

Ruhm CJ (2000) Are recessions good for your health? Q J Econ 115(2):617–650

Shore SH (2009) For better, for worse: intra-household risk-sharing over the business cycle. Rev Econ Stat 92(3):536–548

South SJ (1985) Economic conditions and the divorce rate: a time-series analysis of the post-war United States. J Marriage Fam 47(1):31–41

Stevens AH, Miller DL, Page M, Filipski M (2009) Why are recessions good for your health? Am Econ Rev 99(3):122–127

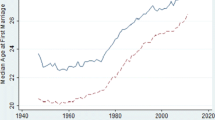

Stevenson B, Wolfers J (2007) Marriage and divorce: changes and their driving forces. J Econ Perspect 21(2):27–52

Stouffer SA, Spencer LM (1936) Marriage and divorce in recent years. The Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 56–69

Weiss Y (1997) The formation and dissolution of families: why marry? Who marries whom? And what happens upon divorce. In: Rosenzweig MR, Stark O (eds) Handbook of population and family economics. Elsevier Science B.V. 81–123

Weiss Y, Willis RJ (1997) Match quality, new information, and marital dissolution. J Labor Econ 15(1):S293–S329

Wolfers J (2006) Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. Am Econ Rev 96(5):1802–1820

Wood RG (1995) Marriage rates and marriageable men: a test of the Wilson hypothesis. J Hum Resour 30(1):163–193

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editor, Erdal Tekin, two anonymous referees, Ann Huff Stevens, Hilary Hoynes, Douglas L. Miller, and seminar participants at the University of California, Davis for their helpful comments and suggestions. I acknowledge financial support from the American Association of University Women American Dissertation Improvement Fellowship and the George and Dorothy Zolk Fellowship in Economics at the University of California, Davis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Erdal Tekin

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schaller, J. For richer, if not for poorer? Marriage and divorce over the business cycle. J Popul Econ 26, 1007–1033 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0413-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0413-0