Abstract

This paper explores the history of ELIZA, a computer programme approximating a Rogerian therapist, developed by Jospeh Weizenbaum at MIT in the 1970s, as an early AI experiment. ELIZA’s reception provoked Weizenbaum to re-appraise the relationship between ‘computer power and human reason’ and to attack the ‘powerful delusional thinking’ about computers and their intelligence that he understood to be widespread in the general public and also amongst experts. The root issue for Weizenbaum was whether human thought could be ‘entirely computable’ (reducible to logical formalism). This also provoked him to re-consider the nature of machine intelligence and to question the instantiation of its logics in the social world, which would come to operate, he said, as a ‘slow acting poison’. Exploring Weizenbaum’s 20th Century apostasy, in the light of ELIZA, illustrates ways in which contemporary anxieties and debates over machine smartness connect to earlier formations. In particular, this article argues that it is in its designation as a computational therapist that ELIZA is most significant today. ELIZA points towards a form of human–machine relationship now pervasive, a precursor of the ‘machinic therapeutic’ condition we find ourselves in, and thus speaks very directly to questions concerning modulation, autonomy, and the new behaviorism that are currently arising.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This joining of an illicit metaphor to an ill-thought out idea then breeds, and is perceived to legitimate, such perverse propositions as that, for example, a computer can be programmed to become an effective psychotherapist’ (Weizenbaum, 1976: 206).

As artificial and human intelligences become more tightly enmeshed, long-standing questions around the application of machine logics to human affairs arise with new urgency. Recently, an accelerating trend towards the modulation of human behavior through computational techniques has gained attention. Explicitly behaviorist nudge-based (Sunstein and Thaler, 2008) social (media) programmes launched by governments ‘for our own good’—and by corporations for theirs—instantiate a therapeutic relationship between computer and human, designed to change human behavior rather than assist in informing autonomous human decision-making or reasoning (Danaher 2017; Yeung 2012; Freedman 2012). Computational modulation, moreover, is also an element in a broader cultural formation; one in which the therapeutic injunction—to change the self—increasingly operates as a pervasive logic. Deploying the computational within various techniques to ‘address’ human issues is part of how we live now; assisted by machines.

The therapeutic also has purchase as a way of conceptualizing evolving human–computer relationships, particularly those concerned with intelligence and its allocation; it constitutes the interface layer in a new intelligence economy. Today developments in AI, bringing new intelligences to contribute to this economy, produce unease in many quarters. Anxieties coalesce around the over-taking of human intelligence by machines, on the one hand (see e.g. Bill Gates, Bill Joy, and Stephen Hawking’s widely publicized pronouncements), and the use of such machines to cement existing forms of human domination and increase un-freedom for dominated groups on the other (see e.g. Dean, 2005). That the prospects for this ‘anxious relationship’ (Bassett 2017) may be configured in therapeutic terms is already established. Howells and Moore rightly identify the therapeutic as a key node of the philosopher Bernard Stiegler’s pharmacological inquiry into technics and the human (Stiegler 2013; Howells and Moore 2013). Stiegler, exploring pharmacology and technology, particularly in What Makes Life Worth Living (2013), argues that computational technology is toxic, but may also be curative (we might say both iatrogenic and potentially remedial), within the cultures it co-constitutes, and co-evolves. Drawing on Winnicott’s object-relations psychoanalysis, Stiegler views computational technology as a transitional object, something simultaneously ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’, through which a mode of engagement with the world may be negotiated.

Others before Stiegler, notably those developing anthropologically informed studies of technology and everyday life in the late 1990s, also drew inspiration from Winnicott, designating various ‘old’ media technologies ‘transitional objects’ (see e.g. Silverstone’s 1993 work on televisionFootnote 1). However it is a tale involving the therapeutic and the specifically computational that is of interest here, and that is brought to bear on current developments.

There are two protagonists in this tale, which begins in the mid 1960s. The first is ELIZA, a ‘chatterbot approximating a Rogerian therapist’ (Wardrip-Fruin 2009). Part of a machine-learning and natural language processing experiment, ELIZA was designed to carry out conversations in English with human users, and was, it was avowed, only a created as a therapist for reasons of research ‘convenience’. Once described as ‘the most widely quoted computer program in history’ (Turkle 1984: 39), ELIZA was a ‘phenomenon’Footnote 2 from the start, gaining something approaching celebrity status in various interested circles. The second protagonist is Joseph Weizenbaum, an MIT computer scientist who came to disavow his artificial progeny. Weizenbaum believed that the reception awarded to ELIZA was unwarranted and misplaced. Notably, the proposition that ‘a computer can be programmed to become an effective psychotherapist’ was ‘perverse’ (Weizenbaum, 1976: 206). The ELIZA events, for him, provided evidence that a mode of ‘powerful delusional thinking’ about computers and their intelligence was circulating in the general public and in the relevant expert communities of computer science/AI and psychology.

ELIZA provoked Weizenbaum to re-assess Artificial Intelligence and its potential impacts. Remaining an advocate of computer science, and of computer autonomy in specific spheres, he became a lifelong critic of untrammeled computational expansion.Footnote 3 In ‘Computer Power and Human Reason’ (1976), the work for which he became best known, he called for limits on the expansion of computational logics and systems into human affairs. In particular, he argued that the desires of the AI community to create intelligent artificial life, and to establish a more fully cybernetic society, were impossible to fully realize, and undesirable in any case. Coming from a scholarFootnote 4 inside one of computer science’s most eminent ‘temples of learning’ this was apostasy. It made for an attack that was distinctively different from the works of critical theorists of technology (Arendt, Ellul, or Mumford for instance), as its author noted; Weizenbaum does not build an abstract critique of technocratic rationality, but works through, and deals with, ramifications for the social world of developments and debates in computer science, centrally those around simulation and intelligence.

In this article, I explore ELIZA, the ELIZA events, and Weizenbaum’s response to them in broadly media archaeological terms. The intention is to let the earlier moment act differently, and thus to re-frame current debates around therapeutic modulation, thereby re-contextualizing the therapeutic in new economies of engagement between various human and non-human controlling ‘intelligences’. What is offered here is thus a history of the present.

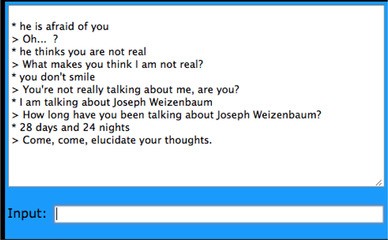

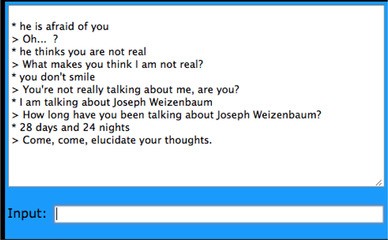

Sources include Weizenbaum’s own writings (CPHR, ACM papers), and the documentary Plug and Pray, in which Weizenbaum’s contemplation on his own mortality is set against the simulated, and possibly immortal, forms of ‘life’ arising in the Bits and Atoms lab at MIT.Footnote 5 Also relevant are later assessments—notably Sherry Turkle’s discussion of ELIZA and its users in the Second Self, which was published in the context of the early Web boom (Turkle, 2005). Alongside these textual resources, there is what may be gleaned through a medium analytic route. This demands attention to be paid to the program, and to ELIZA’s original instantiation on a distributed mainframe system in which exchanges between computer and human user were printed and delivered with what Weizenbaum defined as an ‘acceptable latency’ (Weizenbaum, 1966). The components of ELIZA, and the conditions of its early instantiation, are documented and inform this account. The program may also be explored by re-running it on new platforms, and though emulation has clear limits (‘acceptable latency' changes with time for instance), it has enabled direct interrogation of ELIZA. This is sometimes an oddly compelling enterprise: ‘Come, come’ I am admonished, as I write this article, ‘elucidate your thoughts’…Footnote 6

Two kinds of source material, elements broadly textual and discursive on the one hand, and material on the other, thus inform this article, and also reproduce a tension that was always there; Weizenbaum’s sense was that a false ELIZA narrative had been built up which was at odds with the reality of ELIZA—understood to inhere solely in the function of/functioning of the program. Taking seriously the proposition that ELIZA was more than that, would, he said, be ‘monstrous’ or even ‘monstrously wrong’.

Producing detailed accounts of ELIZA’s workings, he sought to exchange narrative glamour for programming grammar and thus to realign expectations with reality, arguing that:

‘…once a particular program is unmasked, once its inner workings are explained in language sufficiently plain to induce understanding, its magic crumbles away; it stands revealed as a mere collection of procedures, each quite comprehensible.’ (Weizenbaum, ACM).

ELIZA was not magic, could not administer therapy, and it could certainly only simulate a therapeutic relationship. What looked like magic—or ‘life’, or ‘intelligent conversation’—was only a collection of procedures, and this was how its significance should be understood. (Weizenbaum 1966). So Weizenbaum argued. Contra Weizenbaum (although this is in many ways also a sympathetic reading of his position), in this article it is argued that the ascription ‘therapist’, and the discourse it produced, proximately (in operation), and in public (the circulation of ELIZA stories), mattered, and indeed both were an intrinsic part of ELIZA’s constitution.

Moreover, I argue that it is as a computational therapist that ELIZA is significant today. Contemporary anxieties about machine smartness and new forms of artificial intelligence revive the salience of earlier forms of computational anxiety. ELIZA is an early iteration of a form of human–machine relationship now pervasive, a precursor of what I term the ‘machinic therapeutic’ condition we find ourselves in, and thus speaks very directly to questions concerning modulation, autonomy, and the new behaviorism that are currently arising.

Exploring this, in what follows ELIZA and Weizenbaum’s response to ELIZA are first set in the context of then current debates within psychology which set advocates of ‘self-actualization’ against behaviorism with its stress on making the human ‘an object to himself’ (Skinner/Rogers: Dialogue, 1976). I then return to the present to argue that it is relation to the therapeutic, and in relation to the question of the form of the ‘cure’ that we desire, that the ELIZA events revive in salience for us today. Developments in artificial intelligence which enable the further ‘automation of expertise’ (Bassett et al. 2013; Bassett 2013), and the expansion of the ‘droning’ of experience’ (Andrejevic, 2015), are, after all, both forms of the ‘making object’ of human subjects. The rise of computationally driven behaviorist politics, and marketing designed to directly modulate human activities, are only the most obvious manifestations of this more fundamental, if still putative, re-formation.

2 What ELIZA did

ELIZA consisted of a language analyzer and a script or set of rules ‘… like those that might be given to an actor… to improvise around a certain theme’. The resulting bot was designed to undertake real interactions with human interlocutors based on ‘simulation’ or ‘impersonation’ (Weizenbaum 1976: 3). The ELIZA that became synonymous with the name was, strictly speaking, ELIZA running DOCTOR(4), a script setting rules for organizing interactions between a Rogerian analyst and an analysand. Rogerian therapy was thought apt because it draws on extensive forms of mirroring of the patient by the therapist, producing an unusually constrained form of dialogue which is open at one end but closed at the other (Weizenbaum, 1972). This is suitable for natural language-processing experiments because it produces a clear context and demands a limited repertoire of responses which may be ordered in reasonably flexible strings or lists (Turkle, 1984, Weizenbaum, 1976, 1972). In this scenario, if the machine must do the work of simulation, the patient does most of the cognitive work of interpretation. The hope was that ELIZA’s responses, often tendentious or eccentric, might nonetheless seem appropriate in this rather forgiving context.

The NLP ambitions for ELIZA were avowedly modest, but even assessed within these parameters the program had many limitations. It was (and is) easy to ‘trick’, it can be made to loop recursively, and is quickly ‘persuaded’ to come out with nonsensical answers. Claims that ELIZA demonstrated a ‘general solution to the problem of computer understanding of natural language’ (Schank, cited in Weizenbaum 1976: 202), and that it ushered in radically new kinds of smartness in machines, were justifiably claimed by its creator to be egregious. Weizenbaum commented that ELIZA had been ‘shockingly misunderstood’ as a technical advance, and was subject to ‘enormously exaggerated attributions’ (1976: 7). It was not only part of, but also contributed to, a worldview in which the power of artificial intelligences was habitually amplified and the dominance of machine logics lauded. Later, he defined three areas of particular concern.

First, the public ‘success’ of ELIZA contributed to expansion of the influence of the ‘artificial intelligentsia’ with its ‘bombastically exhibited’ hubris (1976: 221). At the core of this ‘hubris’—and at the heart of the AI project—was the goal of the full simulation of human intelligence or equivalent machine intelligence. Weizenbaum thought that taking this as a realistic goal was a fantasy, but a dangerous fantasy. He was concerned about the ascension of the worldview it promoted—one in which man is ‘to come to yield his autonomy to a world viewed as machine’.

That this worldview was established well beyond the artificial intelligence community was also troubling—and he felt it was demonstrated by the enthusiastic response of some professional therapists to ELIZA. Reporting that some psychiatrists believed the DOCTOR computer program could grow into a ‘nearly completely automatic form of psychotherapy’, Weizenbaum lamented that specialists in human to human interaction could ‘…view the simplest mechanical parody of a single interviewing technique as having captured anything of the essence of a human encounter’ (1976: 3). He concluded moreover, that such a response was only possible because the therapists concerned already had a view of the world as machine, and already thought of themselves as ‘information processor(s)’; the outlines of his engagement with behaviorism here begin to appear.

Weizenbaum was also concerned with the inverse of the egregious presumption of high machine intelligence in ELIZA; the imputation of (human-like) life into a machine. Many users related to the program in anthropomorphic ways (1976: 6) he reported, relating to ELIZA as a personality—and a personality, that was, if not precisely a therapist, then at least a helpful interlocutor. Famously, Weizenbaum’s secretary told him to leave the room while she finished her consultation. Sherry Turkle noted that even the ‘sophisticated users’ she talked with, who knew they were interacting with a dumb program, related to ELIZA ‘as though it did understand, as though it were a person’ (1984: 40, 39). Moreover, she suggested that it was precisely ELIZA’s machinic personality that was the allure for her socially averse informants; young computer scientists who did not necessarily want to talk to other human ‘persons’ (Turkle, 2005).

3 Rationality/logicality

Computer Power and Human Reason, combining philosophical inquiry, pedagogical disquisition, and critique, responded directly to these concerns. At its core is a consideration of human versus computer autonomy turning on a rejection of the ‘rationality–logicality equation’ (1976: 365), or the making equivalent of human and machine forms of thinking. The demand is for the maintenance of the recognition of an essential difference between human and machine ‘intelligence’, a refusal of the equating of (human) ‘rational thought’ with (the computer’s) ‘logical operations’ tout court. This produces an attack on the presumption that, because (human) rationality can be understood in terms of (machine) logicality and machine procedures, then the former can be fully operationalized—and reproduced—by the latter. The desire to ‘build a machine on the model of a man… which can ultimately ….contemplate the whole domain of human thought’ (1976: 204), which would operationalize this desire, is characterized as ‘the deepest ‘the deepest and most grandiose fantasy that motivates work on artificial intelligence’ (1976: 203).

This ‘fantasy’, moreover, exposes the reality that formally equating these two forms of intelligence—the human and the artificial—does not produce a working equality between them in practice (even in speculative practice). On the contrary, the result of equating human and macine intelligence is the prioritization of logical operations over human rationality and—therefore—the prioritization of machinic over human values. Challenging this prioritization does not have to entail discarding the logical wholesale: Weizenbaum understood the power of ‘logical operations’ and recognized that these operations would become increasingly autonomous. Moreover, he recognized that their terrain would expand as computers became able to internalize ‘ever more complex and more faithful models of ever larger slices of reality’ (Weizenbaum, 1972: 175). Machine ‘autonomy’ (1976: 610) should be valued, he argued, but its nature should also be more closely addressed.

4 The critique of AI science

Weizenbaum approached the question of the nature of thought through a consideration of the human—naturally enough, given his argument that the most important effect the computer would have on society would be to produce radical changes in ‘man’s image of himself’ (1972, 610), although this was also a somewhat heretical route, given the priorities of his own community at the time. For Weizenbaum ‘whether or not human thought is entirely computable’—that is to say reducible to logical formalism—was a matter of ontology, in marked contrast to then dominant AI approaches based on simulation as a method and a benchmark. Simulation criterion work on the assumption that ‘what looks intuitive can be formalized, and that if you discover the right formalization you can get a machine to do it.’ (Turkle, 2005: 246); there is nothing in the simulation criterion that says a program has to attain human forms of rationality or ‘thought’ to model human behavior or to successfully perform it.Footnote 7 Disputing the existence of transferable—because formalizable—modes of intelligence, and focussing on human ontology, Weizenbaum thus put himself in conflict with the ‘primacy of the program’ or the claim that, as a system, AI could become; ‘as psychoanalysis and Marxism had been…a new way of understanding almost everything’ (Turkle, 2005: 246)Footnote 8; social systems as well as human minds, notably.

For Weizenbaum, the key is not transferability but specificity. He makes an ontological distinction between human intelligence and computer logic, and sees a sharp and unbridgeable division between computer operations (which may exhibit forms of internal autonomy) and human becoming. Human intelligence, not viewed in narrowly mentalist terms, comes to concern embodiment, emotion, recognition and reciprocation. Human ‘smartness’ is unique because entangled with forms of bodily being. This also means that distinctions between human and computer intelligence cannot rely on divisions between emotion and intellect. Both are entailed in what constitutes a specifically human intelligence. Weizenbaum thus also broke with an ‘enduring discourse’ around the divided self (Turkle 1976: 312); human ratiocination is not to fall on the side of ‘that which can be simulated’ while human emotions stand for everything that cannot. Computer logics, autonomous or not, dealing with human emotions or other forms of human cognition or not, are always alienated from human intelligence. Indeed, they are ‘alien’:

‘What could be more obvious…than that the intelligence a computer ‘can muster’, ‘however acquired’ must always and necessarily be…alien to any and all authentic human concerns’? (Weizenbaum, 1976:226).

Weizenbaum’s attack on the rationality–logicality equation is thus conducted through an intervention into thinking around cybernetics (programmable humans and formalizable system logics), a critique of the adequacy of simulation as a measure of AI success, and through the assertion of the ontological distinctiveness of the embodied human and their intelligence. Applying these arguments to ELIZA may be viewed as breaking a butterfly upon a wheel—and in a sense the real targets were elsewhere.

5 Alien logics as discursively prior

Weizenbaum feared that the rationality/logicality equation, not feasible as a route to achieving AI’s goals (as the relative failure of ELIZA underscored), was already operating as a powerful explanatory discourse, impacting on human understandings of their own intelligence and being. As a consequence, the urgent questions arising around computational intelligence, and its diffusion into human streams of consciousness and human societies, were ethical rather than ‘mathematical or technological’ (1976: 661). If they were not addressed, he argued, it was because humans had already ‘made the world too much into a computer’ (1976: ix), and in doing so had ‘abdicated to technology the very duty to formulate questions’. His concern was that the de-prioritization of human values in favour of ‘scientific world-views’ (or the certainty of the program and its solutions) had already become a ‘common sense dogma [that had] virtually delegitimized all other ways of understanding’ (1976: 611).

Weizenbaum thus feared a switch in explanatory mechanisms; the application of ‘alien’ logics to organize properly human affairs and human conflicts. If the presumption is that there are no purely human forms of intelligence, and therefore no ‘human values’ that are incommensurate with machines, then, (notes Weizenbaum), what is really being suggested is that, in an increasingly computational world, ‘the existence of human values themselves’ is not to be allowed (1976: 14). We might say that such values become illegible within the terms of the operational, or dominant, discourse and its language. This might be how ‘equality’ has, in operation, reversed an earlier ‘priority’: Human over machine/machine over human.

The consequences of the switch to machine values are felt at multiple scales and registers. If rational argumentation is really only ‘logicality’, which follows if (human) rationality itself, has been ‘tragically twisted so as to equate it with logicality’ (1976: 13), then human conflicts and disagreements are reduced to ‘failures of communication’ which may best be sorted by ‘information handling techniques’ (1976: 14), and in this way real contradictions are rendered into ‘merely apparent contradiction(s)’ to be ‘untangled by judicious application of cold logic derived from some higher standpoint’ (1976: 13).

What is envisaged is a system where human-held principles or beliefs (for instance in justice, equality, or individual freedom) are increasingly regarded as irrelevant to the administration and/or governance of the society, or of the self. Governance is instead to be accomplished through the embedding of new mechanisms of cybernetic control that may produce resolution, and perhaps what might be termed ‘good order’, without recourse to human judgment. An over-reliance on computational logics could, in short, produce the kind of society in which failing to understand ‘what is distinctive about a human judge, or psychiatrist, what distinguishes them from a machine’ is not recognized as an obvious ‘obscenity’ (1976: 226).

6 The ‘obvious obscenity’: behaviorism and/as control

Computer Power and Human Reason is—explicitly and implicitly—an engagement with behaviorism—notably the behaviorism of B.F. Skinner. This mechanical model of human psychology, influential at the time, was ready ‘to hand’ for AI researchers (1976, 1972) and meshed with their tendency to reverse the human out of the machine. As Weizenbaum noted, over at MIT AI pioneer Marvin Minksy had defined the human as a ‘meat machine’ (see Weizenbaum 1972: 160).

Central to Skinnerian behaviourism is its rejection of an inner self as motivating human actions, and an exclusive focus on genetic endowment and environment. The key to psychological change is conditioning via environmental modification, with the aim being the production of positive feedback loops that generate new forms of good behavior (Skinner 1971). In Skinner’s lab conditioning was undertaken in ‘Skinner boxes’, fully enclosed environments in which pigeon subjects bound into cybernetic circuits of positive behavioral reinforcement learnt to peck for rewardsFootnote 9 (see Bowker 2016; Freedman 2012). However, Skinner argued for societal-wide applications of his work. Behaviorist principles, he argued, should be implemented through the introduction of widespread conditioning mechanisms able to govern societies safely. Social conditioning loops could direct human behaviors towards the ‘right’ ends thereby producing ‘automatic goodness’, this last not a matter of the simulation of (good) intentions, but of engendering concrete actions undertaken by the appropriately conditioned human objects. An extreme expression of this perspective is found in Skinner’s Beyond Freedom and Dignity (Skinner: 1971), published within 3 or 4 years of Human Reason. Reviewing it, under the headline ‘B.F. Skinner says we can’t afford freedom’, Time magazine summed up its message as:

‘…familiar to followers of Skinner, but startling to the uninitiated: we can no longer afford freedom, and so it must be replaced with control over man, his conduct, and his culture’. (Time, 1971).

Behaviorism was in conflict with other therapeutic approaches then current, notably those that sought to work with subjects to raise their capacity for self-knowledge and autonomous action. In particular, person-centred Rogerian therapy, developed by Carl Rogers in the 1940s and 1950s, was hostile to behaviorism and its desire to automate human behavior. Rogerian therapy, inimical to systems-level thinking in general (and, therefore, also at odds with Lacanian-inflected cybernetics), exchanged behavior modification programmes designed to change actions in the external world, for projects of work on the self, to be undertaken by the subject, with the goal of self actualization (2004). The latter being defined as:

‘….the curative force in psychotherapy... man’s tendency to actualize himself, to become his potentialities... to express and activate all the capacities of the organism’ (Rogers 2004).

The differences between these Schools, arising around effectiveness (the discourse of ‘what works’and its justifications) produced fierce disputes over the ethics and morals of therapeutic modulation. Carl Rogers was deeply troubled by the Skinnerian offer of ‘automatic goodness’ (Rogers 1971) as a social ‘cure’ for anything—and concerned by the failure of the Skinner model to engage with questions of commitment. Is the behavior of the ‘freedom rider’ heading down to the US South in civil rights battles attributable only to stimuli and conditioning, he asked?

These issues were argued out between Skinner and Rogers themselves in public debates (see e.g. A Dialogue on Education and Control, 1976). Noam Chomsky also weighed in with ‘The Case Against B.F. Skinner’, a review of Beyond Freedom and Dignity that amounted to a coruscating attack on the social programme of Skinnerism, and which set out to demolish its scientific rigor and denounce the morality of conditioning as a mode of social control (Chomsky 1971).

Skinnerism broke the human down. All there is, said Skinner, is a genetic endowment and an environment, and the latter may be manipulated through environmental programmes, effectively cybernetic loops, designed to produce the desired adaptions in behavior without reference to conscious human decision-making. By contrast Roger’s person-centred therapy engaged with the human and sought to develop their autonomy. The schism between these positions is revived today in relation to debates around emerging forms of behavioral modulation—particularly when it is computer-assisted; a move described by some as a shift from ‘nudge’ to ‘hyper-nudge’ (see Yeung 2012); these debates are the subject of the final sections of the article. But raising the old conflicts also produces a further question about ELIZA;—not whether ELIZA was a therapist at all, but what kind, of therapy could - ELIZA deliver?

7 ELIZA the Rogerian machine?

Two possibilities present themselves. There is ELIZA the automatic therapist, the machine arbiter of human affairs. This is the ELIZA whose (albeit very unformed and/or fictional) existence is said to provide evidence that the behaviorist model of psychology, based on modulation, might, in the future, be operationalized in new ways through computational automation, and that this turn of events might be welcomed by a mis-informed public.

But there is also the ELIZA not only designated—but designed—as a Rogerian rather than a Skinnerian therapist. It was, after all, a Rogerian script that organized the interactions and intersections between human and machine ELIZA organized. And if humans found ELIZA useful perhaps it was as a mirror, a listening surface which enabled forms of self-examination, self expression, or self re-narrativization. If users found something revealing in their interactions with ELIZA then that something was their own: ELIZA never did, and does not now, deliver injunctions, suggestions—or nudges; and has no program to promulgate. Elucidate was all that was said to me.

Admittedly a central tenet of Rogerian therapy is that a relationship of human empathy be generated between analyst and analysand, so ELIZA and ‘her’ computational progeny might always be disqualified from the role of Rogerian analyst by virtue of their alien souls. But there is, nonetheless, something suggestively dissonant in the proposition that the first computational therapist was not programmed to deliver the conditioning proposed by Skinner, and feared by Weizenbaum, but on the contrary offered a rudimentary talking cure. If the ‘intention’Footnote 10 of this computer-delivered ‘artificial’ therapy was not the modulation of a behavior, did it, on the contrary, deal in self-actualization—something like an increase in self? If so, then even if Weizenbaum thought ELIZA was a ‘monster’ she was a monster that was in many ways on his side; perhaps a hopeful monster, in Haraway’s terms (Haraway 1992).

This slide into zoomorphism/anthropomorphism (and gendered ascription) is intended. It gestures towards the importance of registering how ELIZA was experienced by its/her users—and relevant here is both users’ sense of the value of an exchange undertaken between human and machine, and what they were willing to ‘read in’ to the exchanges—the willing presumption by the human speaker that there is a real listener is striking in many transcripts of exchanges. In the place of an ontological schism between machine logicality and human rationality perhaps what arises here, as part of an experience involving code and narration, is a form of ‘x-morphism’ (Laurier and Philo 1999).

ELIZA the Rogerian machine; that impossible thing.

This certainly complicates Weizenbaum’s sense that a misplaced equation (logicality/rationality) will automatically lead to the priority of machine (logicality) over human (rationality). ELIZA indeed, might be said to demonstrate different ways in which the division underpinning that equation fails to hold. In this way what is also signaled is the possibility that a socio-technic relation, that may be termed therapeutic, that does not cleave to either the modulation model nor attach itself to a desire for a purely human form of self-realized autonomy might be generated, might emerge, or might be—cautiously—invoked.

8 Self-actualization versus dronic de-actualization: The renewed salience of therapy wars

ELIZA's visiblity has varied over the past decades.Footnote 11 Today the ELIZA story speaks very directly to how work on the self, modification of the self, adjustment of the self, is undertaken in computational capitalism and to how this work is transforming as accelerating cycles of cognitive automation produce new and increasingly impure (augmented, automated, assembled, x-morphed) streams of consciousness and being; and in doing so raise new questions about control, agency and freedom.

Some of these developments are relatively recent. Calls for responsibilization and a work on the self as a labour of the self—self therapy, self-improvement, and self-direction - were seen as likely to be augmented by the possibilities of computation and its increased efficiencies in the early net era (see Giddens 1991; Miller 2008; Bassett 2009; Mowlabocus 2016). But this injunction has changed. Forms of work on the self that focus on self-labour as a desirable priority are being replaced by explorations of the potentials of direct modulation of the self by a third party—increasingly via computational processes that require neither ‘work’ nor ‘expertise’ on the part of the human (Ruckenstein 2017; Schull 2016), but demand only the submission, of the human, to the process.

This is the context in which a revisionist form of behaviorism may re-emerge and make claims for legitimacy. Nudge is one, now familiar, form in which it is being operationalized. Essentially nudge joins psychology to behavioral economics to produce new tools for governance and markets that very often take software. Moreover, if the therapeutic nudge is emerging as a likely key mechanism to control or modulate data subjects, the new behaviorists, at least those in the mainstream, tend to be more deft than Skinner was, and do not repeat his strident exhortations to society to exchange freedom for control. They stress instead forms of libertarian paternalism orchestrated through ‘choice architectures’ that leave the user ‘free’ to decide not to join the programme, but encouraged to do so (Sunstein and Thaler 2008). The latter have argued fiercely that the nudge is consensual, and it turns out that we often do want to be nudged. As popular and critical commentators have pointed out (see e.g. Freedman in the Atlantic, 2012, Newsweek, 2008) the default option, operating when ‘the chooser chooses not to make a choice’ is powerful precisely because it is much used (Will 2008). However, obvious anxieties arise (and are acknowledged as issues) around the transition from the (consensual) nudge to (involuntarily administered) modificatory push (Sunstein and Thaler 2008).

9 The droning of experience?

Therapy demands work on the self, traditionally work undertaken by the self, with the expert help of another. Behavioral therapy takes the consciously acting self out of that equation so that (for the human at least) the work of change is automated. The human simply experiences an environment and responds to what it introduces. The right response produces a reward. In the case of AI programmes designed to deliver behavioral shifts (computationally delivered nudge programmes for instance), what is evidenced is a re-doubled extension of automation; the taking over by intelligent agents of previously human work, and the replacement of conscious human insight with computational expertise.

In tune with this is Mark Andrejevic’s ‘post-psychoanalytic’ vision of emerging forms of life, in a sensor society, explored through a consideration of the ‘droning of experience’. This can be understood as anticipatory and diagnostic, but also as a commentary on emerging events; the drone, after all, is an excellent figure to get at ‘the people we will become’ inside a new—shinier, bigger, tighter—Skinnerian box (Bowker, 2016). Andrejevic stresses not only the excision of human intellection in new social circuits but the compensatory attention paid to the modulation of human affect—and the forms of being available to the subjects-turned-objects of these circuits.

The discussion takes as a figure lethal automated weapons systems (LAWs), drone systems which work with pre-codified priorities but go ‘raw’ in operation, when they work through an appeal to affective bodily signals rather than tapping the conscious perceptions of human personnel. In the field ‘top down’ human cognitive inputs are thus cut out so that although the human is still in the circuit the controller function has been taken by AI intelligences. This materialization of (human) desires is peculiar;—the weapons give us what ‘we’ ordered, but the desiring human does not speak or cogitate, and the non-desiring machine does not listen. What is put into language, or what emerges into language from the unconscious mind, or inner self, as human ratiocination is irrelevant. Indeed, there is no time afforded for listening to human cogitation; the intention is that identification, analysis, and action are instantaneous in the drone attack. This accelerated temporality is partly why it is designated as an example of the coming into operation of what Andrejevic labels, following Bogost—but here there are sudden echoes of Weizenbaum—a new form of ‘alien thinking’ (Andrejevic, 2015, Bogost, 2012).

The step from LAWs to principles organizing operations across social networks is not difficult to make. Here the direct modulation of the self is undertaken through sentiment and mood analysis—which once again short-circuits conscious intentions or stated desires. The claim is that increasingly these developments, alongside others including neuro-marketing, can turn us into our ‘own intelligent agents’, a process that paradoxically entails giving up conscious agency. The point, as with LAWs, is to ‘…by pass… the forms of conscious reaction and deliberation that threaten to introduce ‘friction’ into the system’ (Andrejevic, 2015: 204).

This, then, is the ‘droning of experience’, and it is intrinsic to the rise of forms of ‘control via the modulation of affect’ that are taken to be an emerging mode of social organization (Andrejevic, 2015). ‘To drone’ is to render human experience into what Andrejevic calls ‘object experience’ through the application of the computational—and, of course, he is not the only one to identify this as a pervasive trajectory currently (see e.g. Kant 2015). What is striking about this account however is that droning is considered, by Andrejevic, as a successor form of therapeutic action—or as ‘post-psychoanalytic’. As I read this, in this vision of a coming world, the self is not helped to actualize (perhaps through computational augmentation) but is rather deleted. The human, now an object in the network, is analysed for the signals it provides, not listened to for what it says, and its trails and traces—its exhausts—are now dealt with rather than being ‘recognized’ or ‘brought to [the human’s] …attention’.

In so far as such forms of operation, such behaviorism, become central to the mediatized organization of experience, then it is justified to claim that while one mode of the therapeutic (that focusing on an inner self) expires, a new mode of therapy, which is based on the prioritizing of one controlling intelligence, and the routing around of another, becomes key to new modes of life. Here is the new centrality of a revived behavioral therapeutic—not a sideshow in discussion of what changed forms or streams of intelligence could, or could not, do, but a central principle through which control is administered today.

10 Remaining non-inhuman beings?

The Skinnerian goal of ‘automatic good’ is thus again taken up, and taken seriously—and once again an indifference to the questions ‘whose good, good for whom, good in what or whose sense?’ becomes (dangerously) acceptable in popular discourse—and a conscious revisionism emerges. This latter re-defines the goals of Skinnerism and re-thinks the morality and ethics of the possible application of behaviorist principles to the wider social world (see e.g. Freedman in the Atlantic). This explicit revisionism is implicit in much of the discussion of the acceptability of Nudge and evident also in debates around neuro-ethics (see e.g. Yeung, 2012).

New ways of automating the modulating of human behavior return to sharp salience the older debates about behaviorism and the mechanical conception of ‘man’ as apt for adjustment—which turn into polemics around existential freedom versus security. Some forms of anti-computing (Bassett 2017), emerging as a response to the computer assisted rise of new forms of behaviorism, reject any role for the computer in the exercise of the therapeutic; in the healing and the changing the self (and this, of course, was Weizenbaum’s position in his time).

A different response, and the one pursued here, responds to the rise of computationally driven behaviorism, taken as an increasingly dominant mode of social therapy, with a question. It seems important to me to ask what other forms of therapeutic engagement, between human and intelligent machine, might there be? And how might such engagements assist in generating new forms of life in a world of hybrid and impure streams of consciousness?

This returns me to ELIZA, by design not a Skinnerian machine remember, but also, as a machine, unable to fully deliver that form of human empathy a Rogerian therapist might; and indeed ELIZA in the end would be quite incapable of generating the forms of fully human authenticity that Roger’s atomistic concentration on a prior inner self-demanded (see Geller 1982). So, a transitional machine perhaps. Earlier I said ELIZA might be a hopeful monster precisely because, as a Rogerian Machine, she appeared impossible, but worked. In that role we might say ‘she’ succeeded (in the past), and succeeds again now, in provoking a re-think of polemical positions around the computational therapeutic.

Thinking about ELIZA as transitional object points to ways to re-think the engagement between therapy and technology. It suggests that a ‘cure’ for the position we find ourselves in, in relation to this world, which is itself poisoned by technocratic rationality, might be found in part through the technological as also curative. The point would be the generation of a mode of therapy which does not cleave entirely either to the narrative (cure) and the human rationale, nor to the logical operations laid down in code that would automate expertise and experience so that we are only ever moved by technology, rather than improving—or finding—or augmenting ourselves through it.

On the other hand, this object-designation (‘transitional object’) downplays ELIZA’s own agency, limited as it was—and perhaps therefore, the specificity of this media technology—which is after all its artificial intelligence. So I would prefer to continue to understand ELIZA as a therapist. In this form, ELIZA does offer a commentary—and one different from Weizenbaum’s own—on contemporary developments.

To the extent that they appear to resonate with real trends, Weizenbaum’s fears that the reading of logical operations and human intelligence as equivalent would increasingly produce a prioritization of the alien intelligence of the computer, so that what began as equality would become domination, appear to be justified. On the other hand, as we have argued, his demand to cut ELIZA down to size by insisting on an exclusive focus on procedures ignored what else was going on. There was the code. But there was also the story. Perhaps we might say that, if ‘ELIZA’ was code, then ‘Eliza’ was the comfort found in the machine, by humans, who built a different kind of relationship with ‘her’ that exceeded what the procedures of code offered, precisely because code came into contact with human thought. ‘Eliza’ against ELIZA then; conflicted from the start. No wonder she was such a mess. But this conflict may be read in positive terms. You might say that ELIZA, in-human as ‘she’ is, contributes to the efforts of those ‘trying to remain non-inhuman beings’ (Stiegler 2013: 4) in a computational world.

Notes

Lines of inquiry in new media studies continue to develop (see e.g. Mowlabocus, 2016).

ELIZA took its name from the heroine of Shaw’s Pygmalion—the intention being that it might learn from its interactions (Weizenbaum, January, 1966). The ‘phenomenon’ was a character, in Dickin’s Nicolas Nickelby, notable for her much-lauded and recorded infant achievements.

Weizenbaum parallels his own career history with that of Polyani. The latter was a chemist whose engagement with discussions about the mechanical conception of man began as a single intervention—an argument with Bukharin—but became a lifelong concern (Weizenbaum, 1976).

SLIP (Symmetric LIst Processor) is a list-processing computer programming language developed by Weizenbaum in the 1960s. It was first implemented as an extension to the Fortran programming language, and later embedded into MAD and ALGOL. ELIZA was written in SLIP (Weizenbaum, 1966).

This documentary on Weizenbaum brings into relation contemporary developments in AI and robotics and Weizenbaum’s own cogitations on Eliza and AI in general. It is wound around two trajectories; the robotic doppelganger of the scientist Ishiguro at the Bits and Atoms lab of MIT, who is slowly coming to a form of life, and the death—the human end—of Weizenbaum himself. Issues thus arise about how much liveliness there might be to go around.

The intersection between theories of the performative production of human selves and questions of agency intersect here in interesting ways; one of the early critiques of Butler’s initial conceptions of performativity as subjectivity was that it left no space for agency within the constraints of a discourse that produces the subject it names. (see Butler’s Gender Trouble, 1993).

Turkle notes she uses this term to refer to ‘ a wide range of computational processes, in no way limited to serial programs written in standard programming languages.’ (Turkle, 2007: 246).

There is no assertion here that ELIZA the therapist had intentionality, but in so far as the program set out to effectively undertake an interaction within the Rogerian register intention was involved.

Today renewed interest in ELIZA, and in Weizenbaum’s own story, is a symptom of ‘automation anxiety’ (Bassett, Roberts, Pay, 2017) currently in evidence, triggered by developments in AI and new waves of cybernation.

References

Adams C, Thompson TL (2016) Researching a Posthuman world: interviews with digital objects. Palgrave, London

Anderson C (2008) The end of theory: the data Deluge Makes the scientific method obsolete. Wired Magazine, June 23. http://www.wired.com/science/discoveries/magazine/16-07/pb_theory. Accessed 30 Aug 2008

Andrejevic M (2015) The droning of experience. Fibercult J 25:FCJ-187

Bassett C, Fotopoulous A, Howland K (2013) Expertise, a scoping study. Working Papers of the Communities and Culture Network+. http://www.communitiesandculture.org

Bassett C (2013) ‘Feminism, expertise and the computational turn’. In: Thornham H, Weissmann E (eds) Renewing feminism: narratives, fantasies and futures. IB Tauris, London, pp 199–214

Bassett C (2009) Up the garden path, or how to get smart in public. Second Nature 2

Bassett C (2017) The first time as argument: automation fever in the 1960s'. Paper to Human Obsolescence Workshop. Sussex Humanities Lab. http://www.sussex.ac.uk/shl/projects/

Battalio RC et al (1981) ‘Income Leisure Tradeoffs of animal workers’. Am Econ Rev 621–632

Berlin I (1998) Two concepts of liberty. In: Hardy H, Hausheer R (eds) The proper study of Mankind. Pimilico, London

Boyd D, Crawford K (2012) Critical questions for big data. Inf Commun Soc 15(5):662–679

Bowker G (2016) Just what are we archiving, LIMN 6. http://limn.it/just-what-are-we-archiving/

Bogost I (2012). Alien phenomenology, or, what it’s like to be a thing. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press

Butler J (2002). What is critique? An essay on Foucault’s virtue. In: Ingram David (ed) The political: readings in continental philosophy. Basil Blackwell, London. http://eipcp.net/transversal/0806/butler/en

Butler J (1993) Gender trouble. Routledge, London

Chomsky N (1971) The case against. In: Skinner BF, The New York review of books (December 30)

Chomsky N (1971) Skinner’s Utopia: Panacea, or Path to Hell?’ in Time magazine (September 20)

Danaher J. The threat of Algocracy: reality, resistance and accommodation. Philos Technol 29(3) 245:268

Danaher J (2017) Algorcracy as hypernuding: a new way to understand the threat of algocracy. Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies. http://www.ieet.org/inde.php/IEET2/more/Danaher20170117

Dean J (2005) Communicative capitalism: circulation and the foreclosure of politics. Cult Polit 1(1):51–74

Foucault M (1997) ‘What is critique?’ In: Lotringer S, Lysa H (eds) The politics of truth. Semiotext(e), New York

Geller L (1982) The failure of self actualization theory. J Human Psychol 22(2):56–73

Giddens A (1991) Modernity and self-identity. Polity, Cambridge

Freedman DH (2012) ‘The perfected self’. In: The Atlantic, June 2012. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive

Haraway D (1992) The promises of monsters: a regenerative politics for inappropriate/d others. In: Grossberg L, Nelson C, Treichler PA (eds) Cultural studies. Routledge, New York, pp 295–337

Howells C Moore G (2013) Stiegler and Technics. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Kant T (2015) Spotify has added an event to your past’: (re)writing the self through Facebook’s autoposting apps. Fibrecult J (25). ISSN 1449–1443

Knuth DE (1997) The Art of computer programming: volume 1: fundamental algorithms

Laurier E, Philo C (1999) ’X-morphizing: review essay of Bruno Latour’s ‘Aramis, or the Love of Technology’. Environ Plan A 31:1047–1072

Leonard TC (2008) ‘Richard H. Thaler, Cass R. Sunstein ‘Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness’. Review. Const Polit Econ 19:365–360

Miller V (2008) ‘New media, networking and phatic culture’. Convergence 14(4):387–400

Mowlabocus S (2016) ‘Mastery of the Swipe’. First Monday, 21(10)

Ruckenstein (2017) Beyond the Quantified Self: Thematic exploration of a dataistic paradigm. New Media Soc 19(3):401–418

Rogers C (2004) On becoming a person. Constable, London

Schanze J (2010) Plug and pray documentary film, (Director)

Schull N (2016) Data for life: wearable technology and the design of self care. BioSocieties 11:(3)317–333

Searle J (1980) ‘Minds, brains and programs’. Behav Brain Sci 3(3):417–457

Silverstone R (1993) Television, ontological security and transitional object. Routledge, London

Skinner BF, Rogers C (1976) A dialogue on education and control (YouTube)

Skinner BF (1971) Beyond freedom and dignity. Knopf, New York

Steigler B (2013) What makes life worth living: on pharmacology. Oxford, Polity

Sunstein CR, Thaler RH, (2008) Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. Penguin, London

Skinner BF (1971) ‘B.F. Skinner says we can’t afford freedom’. Time Magazine cover September 20, 1971, vol 98(12)

Turkle S (2005) The second self, computers and the human spirit. Weidenfeld, New York

Wardrip-Fruin N (2009) Third person: authoring and exploring vast narratives. MIT, London

Weizenbaum J (1976) Computer power and human reason, from judgment to calculation. WH. Freeman, San Francisco

Weizenbaum J (1966) ‘ELIZA—a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine’. Commun ACM 9(1):36 – 35 (January 1966)

Weizenbaum J (1972) ‘How does one insult a machine?’ Science 176:609–614

Weizenbaum J (1966) ELIZA—a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Commun ACM (CACM homepage archive) 9(1):36–45. http://cacm.acm.org/

Wing JM (2006) Computational thinking. Commun ACM 49(3):33–35

Will GF. Nudge against the fudge, Newsweek, 6.21.2008. http://www.newsweek.com/george-f-will-nudge-against-the fudge-90735

Yeung K (2012) Nudge as fudge, review article. Modern Law Rev 75(1):122–148

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bassett, C. The computational therapeutic: exploring Weizenbaum’s ELIZA as a history of the present. AI & Soc 34, 803–812 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-018-0825-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-018-0825-9