Abstract

Purpose

The relationship between ethnicity and adolescent mental health was investigated using cross-sectional data from the nationally representative UK Millennium Cohort Study.

Methods

Parental Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire reports identified mental health problems in 10,357 young people aged 14 (n = 2042 from ethnic minority backgrounds: Mixed n = 492, Indian n = 275, Pakistani n = 496, Bangladeshi n = 221, Black Caribbean n = 102, Black African n = 187, Other Ethnic Group n = 269). Univariable logistic regression models investigated associations between each factor and outcome; a bivariable model investigated whether household income explained differences by ethnicity, and a multivariable model additionally adjusted for factors of social support (self-assessed support, parental relationship), participation (socialising, organised activities, religious attendance), and adversity (bullying, victimisation, substance use). Results were stratified by sex as evidence of a sex/ethnicity interaction was found (P = 0.0002).

Results

There were lower unadjusted odds for mental health problems in boys from Black African (OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.04–0.61) and Indian backgrounds (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.21–0.86) compared to White peers. After adjustment for income, odds were lower in boys from Black African (OR 0.10, 95% CI 0.02–0.38), Indian (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.21–0.77), and Pakistani (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.27–0.89) backgrounds, and girls from Bangladeshi (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.05–0.65) and Pakistani (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.41–0.99) backgrounds. After further adjustment for social support, participation, and adversity factors, only boys from a Black African background had lower odds (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.03–0.71) of mental health problems.

Conclusions

Household income confounded lower prevalence of mental health problems in some young people from Pakistani and Bangladeshi backgrounds; findings suggest ethnic differences are partly but not fully accounted for by income, social support, participation, and adversity. Addressing income inequalities and socially focused interventions may protect against mental health problems irrespective of ethnicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As mental health problems such as anxiety and depression often first manifest by adolescence, an improved understanding is required to address inequalities and achieve lifelong beneficial effects for young people [1,2,3,4]. In England, the prevalence of mental disorder is higher in children aged 5–19 from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds, who are also more likely to experience problems with family functioning, adverse life events, and reduced social support and participation. However, the overall prevalence of mental health problems is lower for children from Black and Asian backgrounds compared to their White British peers [5].

A large body of evidence has explored associations between strong social relationships and better mental health, and experience of social adversity and socioeconomic disadvantage with worse mental health [6]. The relationship between ethnicity and mental health remains more complex. In the UK, people from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to face socioeconomic adversity than their White British peers, and are more likely to be living in deprived areas [7]. Ethnic minority status exposes young people to experiences of racism, discrimination, and social marginalisation, which have been associated with adverse mental health problems [8, 9]. The lower prevalence of mental health problems in young people from some ethnic minority groups therefore run counter to expectation.

The last systematic review of ethnic inequalities in child and adolescent mental health found that children from Black African and Indian backgrounds had better mental health, while children from Mixed, Black Caribbean, Pakistani and Bangladeshi backgrounds had similar levels of mental health problems, compared to their White British peers; overall no disadvantage in mental health problems was found in these groups, despite the overall increased adversity that might otherwise predispose them to developing problems [10].

Evidence has remained mixed in the decade since: in east London, young people from Bangladeshi and Indian backgrounds had a reduced likelihood of reporting psychological distress and mental health problems, whereas those from White Other backgrounds had a higher likelihood, compared to their White British peers [11, 12]. Investigators in another London wide study observed a lower prevalence of mental health problems in boys from Black Caribbean, Nigerian, and Ghanaian backgrounds, and girls from Indian backgrounds [13].

Findings of lower prevalence of mental health problems in some ethnic minority adolescents are persistent across studies using different instruments to measure mental health. However, data from highly diverse, multi-cultural urban contexts such as London have largely been used in investigations to date, which may not have captured national differences. To address this, data were analysed from the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS), a multi-purpose longitudinal study following a large, nationally representative sample of young people. This is the first analysis exploring the potential explanatory mechanisms of social support, participation, and adversity behind the relationship between ethnicity and mental health, by investigating young people’s self-reported social activities, relationships, and lifestyle.

We hypothesised that there would be lower prevalence of mental health problems in young people from some ethnic minority backgrounds compared to White peers, and that these associations would be attenuated by adjustment for factors of social support, participation, adversity, and household income.

Methods

Data source

The MCS is a nationally representative longitudinal birth cohort study, following children born across the UK between 2000 and 2002. Using the child benefit register as sampling frame, MCS covered most of the child population except those not registered due to recent, temporary, or irregular immigration status [14]. A stratified, clustered, random sampling strategy, purposefully oversampling economically disadvantaged and ethnically diverse areas (where ethnic minority representation was over 30% in the 1991 census) was used. Further information is provided in survey documentation from the Centre for Longitudinal Studies (CLS) [15].

From an initial 19,519 participating families, responses in the sixth sweep were provided by 11,884 families, which collected information on cohort members aged around 14 years. Data collection was conducted between January 2015 and April 2016. This analysis used data from parent responses to the Household and Parental Questionnaire, and self-completed responses by cohort members to the Young Person Questionnaire.

Measures

Mental health problems were measured through parent responses to the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), a validated psychometric tool providing a dimensional measure of mental health in children aged 3–16 [16]. Scores are measured for 25 items over conduct, hyperactivity/inattention, emotional, peer, and pro-social problems subscales. Scores across all except the pro-social subscale are added to obtain a Total Difficulties Score (TDS), between 0 and 40; TDS of 17 or above is indicative of probable clinically diagnosable mental disorder [17]. The SDQ is widely used in child and adolescent mental health research, and other studies investigating ethnic mental health inequalities [18].

Eight harmonised categories derived by MCS, based on Office for National Statistics categories used by young people to self-report ethnicity, were used to describe ethnic background: White (including White British, Irish, Gypsy or Irish Traveller, and White Other), Mixed (including any multiple ethnic background), Black African, Black Caribbean, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and Other Ethnic Group (including Arab, Chinese, Other Black, or Other Asian).

Household income was measured using Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) equivalised income quintiles, which adjusts weekly household income data according to size, composition, and resource needs. Similar equivalisation indicates comparable standards of living [19].

Social support and participation factors

To measure social support, cohort members were asked three question items from the Social Provisions Scale, detecting presence and absence of social support: ‘I have family and friends that help me feel safe, secure, and happy’; ‘There is someone I trust whom I would turn to for advice if I were having problems’; ‘There is no one I feel close to’ [20]. Responses ranged from ‘Very true’, ‘Partly true’, and ‘Not true at all’. Scores were summed for questions detecting presence and reversed prior to summing for absence. Higher scores correlate to a greater degree of social support. Total scores of 8–9 were used to indicate strong social support, 6–7 for some social support, and 5 or less as indicative of little to no social support.

To assess parental relationship, responses to the question ‘Overall, how close would you say you are to your mother/father?’ were grouped as: ‘Not close to either parent/no parents’, ‘Close to one parent’, or ‘Close to both parents’.

Social participation was measured through amount of time cohort members spent with friends outside school, in organised activities such as youth clubs, scouts, girl guides or other activities, and attendance of a religious service.

Social adversity factors

Bullying was measured as the current frequency of being picked on or hurt by other children, received unwanted or nasty online or social media communications, and a separate bullying measure for having been the perpetrators of these actions.

Victimisation was measured through the cumulative number of experiences of being insulted, called names, threatened, or shouted at in a public place, school, or elsewhere, physical violence, having something stolen, unwanted sexual approaches or sexual assault in the past year.

Substance use was measured as number of experiences of smoking of 1–6 cigarettes a week or more, drinking 5 or more alcoholic drinks at one time, trying cannabis more than 5 times, and trying any other illegal drugs in the past year.

Statistical analyses

Analysis was conducted in Stata 14. Survey weights were applied to address sample design, and bias related to sampling and attrition [15]. Further weighting information can be found in survey documentation [21].

Distribution of all measures by ethnicity was described. Pearson Chi-squared tests initially assessed any differences here, and for crude associations between each measure and having mental health problems (see Supplementary table 1). Univariable logistic regressions were then used to investigate unadjusted measures of effect of ethnicity, sex, income, and all social factors with mental health problems respectively.

In the adjusted analysis, a bivariable logistic regression model was used to explore the relationship between ethnicity and mental health problems adjusted for household income only, and a multivariable model additionally adjusted for income and all social factors (originally, models separately tested social support and participation factors and social adversity factors, which were both, respectively, significant, so were included altogether here).

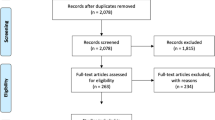

Wald tests were applied to assess overall associations of each factor with the outcome. We assessed interactions between ethnicity and sex across all models and found evidence in support of effect modification. Sex stratified results are therefore presented across all adjusted models. Complete case analysis of data from 10,357 cohort members (87.2% of the overall cohort), who provided complete information across all measures, was conducted (Fig. 1).

Finally, we conducted a series of supplementary analyses assessing count of symptoms using Poisson regression to investigate the SDQ total score, externalising and internalising subscales as linear measures of mental health outcomes as a sensitivity analysis.

Results

Of the total sample of 10,357 young people, n = 5298 (49.6%) were female and n = 5059 (50.4%) were male (survey weighted proportions are detailed here, see Table 1). 2,042 were from ethnic minority backgrounds: n = 492 (5.4%) Mixed, n = 275 (2.1%) Indian, n = 496 (3.3%) Pakistani, n = 221 (1.4%) Bangladeshi, n = 102 (1.3%) Black Caribbean, n = 187 (2.3%) Black African, and n = 269 (2.8%) Other Ethnic Group backgrounds, respectively; n = 8315 (81.5%) were from White backgrounds, considered the reference group.

Social factors largely varied by ethnicity, as detailed in Table 1. Remarkably high proportions of young people from Bangladeshi (70.2%) and Pakistani (64.2%) backgrounds were in the lowest household income quintile, and higher proportions of those from Black African (47.4%), Black Caribbean (40.2%), and Other Ethnic Group (31.9%) backgrounds were also in this category, compared with White peers (13.1%). Young people from a Bangladeshi background were the largest proportion (87.6%), and those from a Black Caribbean background the smallest proportion (54.8%), reporting being close to both parents (79.1% in White peers). Overall, while findings were mixed for social support and organised activities, except for those from Mixed backgrounds, smaller proportions of all young people from other ethnic minority backgrounds reported spending time weekly with friends outside school. Larger proportions of those from all ethnic minority backgrounds spent time weekly in religious attendance. Larger proportions of those from ethnic minority backgrounds (except for those from Mixed backgrounds) reported they had never been the victim of bullying (findings were mixed on being a perpetrator) and had no experiences of victimisation or substance use (see Supplementary Tables 2, 3 for breakdown of social factors by sex).

Differences in prevalence of mental health problems according to each social factor are provided in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table 1). Prevalence of mental health problems was 9.9% (95% confidence intervals (CI) 9.1–10.6%) for all cohort members, which was lower in girls at 9.0% (95% CI 8.0–10.0%) and higher in boys at 10.9% (95% CI 9.6–12.2%). Prevalence varied by ethnicity and was indicatively highest in young people from Black Caribbean backgrounds at 15.8% (95% CI 8.8–26.9%) and lowest in those from Black African backgrounds at 2.9% (95% CI 1.1–7.3%).

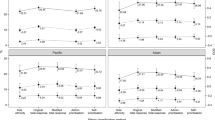

In the unadjusted logistic regression analyses of outcome and ethnicity, there were significantly lower odds of mental health problems for Black African (odds ratio (OR) 0.15, 95% Cl 0.04–0.61) and Indian (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.21–0.86) boys, compared to their White peers (model 1, Table 2). Lower odds were also found in boys from Mixed and Pakistani backgrounds, and girls from Bangladeshi, Black African, and Indian backgrounds; higher odds were found in boys from Bangladeshi, Black Caribbean, and Other Ethnic backgrounds, and girls from Mixed, Pakistani, Black Caribbean, and Other Ethnic backgrounds, however the 95% confidence intervals for these OR estimates were wide.

Across unadjusted logistic regression models of outcome by each social factor, young people in the lowest income quintile had higher odds of having mental health problems compared with those in the highest (OR 4.98, 95% CI 3.55–6.99). Higher odds of mental health problems were also seen in those reporting weaker parental relationships (OR 3.13, 95% CI 1.91–5.13) and spending less time with friends outside school (OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.56–3.25), than those with strong relationships or more frequent social activity, as did those who reported never participating in organised activities (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.11–1.69) or attending religious services (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.46–2.54) compared to those who participated in these activities at least weekly, and for those reporting lower levels of social support compared to higher support (OR 4.36, 95% CI 2.42–7.86), frequent bullying (OR 7.46, 95% CI 5.62–9.89) or being a bully (OR 7.11, 95% CI 4.18–12.08) compared to never being a victim or a perpetrator of bullying, and three or more experiences of victimisation (OR 4.06, 95% CI 3.11–5.30) and substance use (OR 6.05, 95% CI 3.58–10.23) compared to no experiences of these, respectively (see Table 3 for full details).

On adjustment for household income (model 2, Table 2), odds for having mental health problems were lower in girls from Bangladeshi (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.05–0.65) and Pakistani (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.41–0.99) backgrounds, and boys from Black African (OR 0.10, 95% CI 0.02–0.38), Indian (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.21–0.77), and Pakistani (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.27–0.89) backgrounds, compared to their White peers. Though confidence intervals for point estimates were wide and overlapping, effect size decreased for those from Other Ethnic Group, boys from Black Caribbean, and girls from Mixed backgrounds; effect size increased for boys from Mixed backgrounds and girls from Black African and Indian backgrounds. Odds were lower for girls from Black Caribbean backgrounds in this model, which was the opposite of the unadjusted findings.

After adjustment for all social support, participation, and adversity factors, together with household income (model 3), only boys from Black African backgrounds had significantly lower odds of having mental health problems compared to White peers (OR 0.16, 95% CI: 0.03–0.71, Table 2). ORs for young people from other backgrounds were largely similar to those obtained in the unadjusted analysis (model 1). There was also a dose–response relationship between greater experiences of bullying (both being victim and perpetrator) and victimisation and poorer mental health (estimates are attenuated on full adjustment, but associations remain).

Logistic regression results are reported here given the rare disease assumption (prevalence below 10%) remains valid for this investigation of mental health outcomes. However, sensitivity analysis repeating the above models using Poisson regression, assessing the SDQ as a linear measure modelling count of symptoms for total score, internalising, and externalising subscales found similar results by ethnicity and sex. Results broadly followed the same direction, however girls from Black African backgrounds in the fully adjusted Poisson regression had a lower total score symptom count, which was not seen from the logistic regression given very wide 95% confidence intervals around the OR. This reflected some improved power in the former approach. In fully adjusted Poisson regression for the internalising subscale, girls from Indian and Black African backgrounds had lower symptom counts, and boys from Pakistani and Other Ethnic Group backgrounds had higher symptom counts compared to White peers, whereas for the externalising subscale, no significant differences were found by ethnicity though the estimates largely followed same patterns at the logistic regression results (see Supplementary Tables 4–6).

Discussion

Household income was the factor associated with the most substantial changes in effect sizes. The lower odds of having mental health problems in all young people from Pakistani backgrounds and girls from Bangladeshi backgrounds compared to their White peers were seen after adjustment for income (in the unadjusted analysis, Bangladeshi boys and Pakistani girls had higher odds, whereas Bangladeshi girls and Pakistani boys had lower odds, though these estimates had wide confidence intervals). For boys from Indian and Black African backgrounds who had a lower unadjusted odds of having mental health problems, adjusting for income demonstrated a larger effect size; this was also noted in groups for whom lower odds estimates had wide confidence intervals. Similarly, for those who had higher odds estimates with wide confidence intervals, estimates moved closer to the null after adjusting for income. These findings support existing research suggesting ethnic inequalities in mental health are closely related to but not entirely explained by other socioeconomic inequalities [22]. Overall, social support and participation factors were associated with better, and social adversity with worse, mental health outcomes for this nationally representative, ethnically diverse cohort of young people.

There is also very weak evidence of higher prevalence of mental health problems in young people from Black Caribbean and Other Ethnic Group backgrounds, and girls from a Mixed ethnic background. Due to small sample sizes, actual differences remained undetected. These differences are important to investigate further, given that the latest adult data indicate a higher prevalence of common mental disorders in Black and Black British women, and a lower prevalence in White Other women; the prevalence of psychosis is also higher in Black men, compared to White British men [23].

Initial MCS findings at age 14 found that 24% of girls and 9% of boys reported experiencing high levels of depressive symptoms as measured by the Short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire; young people from Asian backgrounds and girls from Black backgrounds were less likely to have high levels of depressive symptoms [24]. Similar results were found by ethnicity in this analysis, however, increased mental health problems were observed in boys here, as indicated by the SDQ, which captures conduct disorders. This difference emphasises the importance of potential mediating mechanisms between gender, social factors, and their impact on mental health outcomes in the transitional period of adolescence, which warrant further investigation (as gender could not be explored beyond the binary sex category available for analysis) [25].

Some of the observed ethnic differences seem to be partly explained by the social factors investigated here, as seen in the estimates in model 3 (adjusted for income and all factors) moving towards the null compared to model 2 (adjusted for income only) for girls from Bangladeshi and all those from Black African, Indian, and Pakistani backgrounds, although confidence intervals overlapped. As differences remained partly but not fully explained, further analyses of mediating mechanisms should be taken to improve understanding. Similar observations have been made in east London, where bullying and social support from families was found to be more important for mental health, whatever the participants’ ethnicity or culturally influenced friendship choices [11]. Experience of racism was an adverse influence, whereas family relationships, religious participation, and ethnically diverse friendships were protective influences for young people from all ethnic backgrounds across London [26].

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first focused analysis of ethnicity and mental health in a nationally representative cohort of young people, indicating that further investigation of the social factors explored here is needed, as these factors could partly but not fully explain mental health differences observed by ethnicity. Further strengths include generalisability of findings regarding experiences of social support, participation, and adversity.

Despite oversampling to boost ethnic minority representation, the very small sample sizes mean this analysis may be underpowered to detect differences. Ethnic diversity in the UK has changed considerably since 2000, when this birth cohort was recruited. Diverse populations have been homogenised into limited categories which have varying levels of relevance for individuals. The Black African, Black Caribbean, Mixed, and Other Ethnic Groups, amongst others, encompass immense diversity. The White group includes young people from Irish, White Other, and Gypsy or Irish Traveller backgrounds, who have been noted to have different mental health and social outcomes to White British adolescents [12]. Recently migrated or undocumented young people were not included. These findings should be critically appraised in recognition of this complex heterogeneity of cultures, class status, and migration histories [27, 28], as essentialising these differences runs the risk of racial determinism [29, 30].

Processes of socialisation vary between and within cultures, however cultural identity and community specific norms that are underlying the social factors explored here could not be assessed in this analysis. The complex relationship between intergenerational dynamics and mental health was not assessed. While ethnic density (the proportion of people from a given ethnic background resident in a given area) and the related social cohesion this may represent has been associated with lower prevalence of common mental disorders in adults, evidence is mixed for adolescents and was not explored here [31, 32]. It is important to note that patterns of lower prevalence of mental health problems are not maintained into adulthood. The cumulative impact of different forms of adversity and discrimination, including racism over the life-course, interacting with persisting barriers to social mobility may be potentially driving such trends [33, 34]. No questions were directly asked about young people’s experiences of racism in this survey wave; maternal and family experiences of racism were found to affect children’s socioemotional development for this cohort [35]. Monitoring changes across the life-course is important, moreover as compared to White British peers, ethnic minority children and young people are more likely to access mental health services through compulsory routes, reflecting inequalities found in adults [36].

All measures were mostly self-reported by young people and parents, so were subject to reporting bias. A key limitation was lack of young people’s self-reported SDQ responses, to compare and corroborate results with parent reports given their respective biases. Despite widespread application across international contexts, evidence remains limited on SDQ construct validity for adolescents across cultures and languages in the UK context (with only one study reviewing it as valid in adolescents from Indian backgrounds) [37] and whether parental willingness to report negative behaviours is associated with ethnicity, given mental health related stigma reported in ethnic minority groups [38]. The SDQ was not systematically translated for those with limited English, and differences in idioms of mental distress across populations may not have been captured [21, 39].

Cross-sectional analysis of a single sweep of a longitudinal study meant that the temporal sequence of risk factors could not be established. Furthermore, in light of the recent unequal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and response measures taken in the UK, which has resulted in a disproportionately greater loss of income in ethnic minority groups who were already overrepresented in disadvantage, monitoring income inequalities is particularly important [40]. In future, there will be a potential to address these limitations and follow the same participants, in the age 17 and 22 sweeps of the MCS.

Conclusions

Household income confounded the lower prevalence of mental health problems apparent in some young people from Bangladeshi and Pakistani backgrounds compared to White peers; lower prevalence was also noted in some young people from Black African and Indian backgrounds, for whom effect sizes were stronger after adjusting for household income. There was some evidence of a higher prevalence of mental health problems in young people from Black Caribbean, Mixed, and Other Ethnic Group backgrounds which should be investigated further, given patterns of ethnic inequalities in mental health observed in adulthood.

These findings suggest these ethnic inequalities in mental health outcomes could be partly but not fully explained by social support, participation, and adversity factors. Further analysis of mediating mechanisms and differences by gender should be closely monitored. For example, where young people find social support is often also where they experience social adversity [41]: supportive friendships can turn into sources of risk if peer groups encourage risky behaviours, and the adolescent-parent relationship can be a source of stress. Social participation is increasingly conducted online; while only negative influences of social media in cyberbullying was considered here, the role of social media in facilitating potentially beneficial social interactions for wellbeing could be investigated further.

Overall, interventions that seek to tackle household income inequalities (such as improved housing and financial support for struggling families) and prevent bullying and victimisation in particular (for example across school, community, and social media settings) may support young people against mental health problems, irrespective of ethnicity.

Data availability

MCS6 is deposited with the UK Data Service at the University of Essex.

Code availability

Analysis code can be made available on request.

References

Clark C, Rodgers B, Caldwell T et al (2007) Childhood and adulthood psychological Ill health as predictors of midlife affective and anxiety disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:668. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.6.668

Maughan B, Kim-Cohen J (2005) Continuities between childhood and adult life. Br J Psychiatry 187:301–303. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.187.4.301

Neufeld SAS, Dunn VJ, Jones PB et al (2017) Reduction in adolescent depression after contact with mental health services: a longitudinal cohort study in the UK. Lancet Psychiatry 4:120–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30002-0

Knapp M, Snell T, Healey A et al (2015) How do child and adolescent mental health problems influence public sector costs? Interindividual variations in a nationally representative British sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip 56:667–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12327

Sadler K, Vizard T, Ford T et al (2018) Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2017 Summary of key findings. NHS Digital

Reiss F (2013) Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 90:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026

Jivraj S, Khan O (2013) Ethnicity and deprivation in England: How likely are ethnic minorities to live in deprived neighbourhoods? Briefing paper, The Dynamics of Diversity: Evidence from the 2011 Census series. Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity, University of Manchester

Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B et al (2013) A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Soc Sci Med 95:115–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031

Astell-Burt T, Maynard MJ, Lenguerrand E, Harding S (2012) Racism, ethnic density and psychological well-being through adolescence: evidence from the determinants of adolescent social well-being and health longitudinal study. Ethn Health 17:71–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2011.645153

Goodman A, Patel V, Leon DA (2008) Child mental health differences amongst ethnic groups in Britain: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 8:258. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-258

Bhui K, Silva MJ, Harding S, Stansfeld S (2017) Bullying, social support, and psychological distress: findings from RELACHS Cohorts of East London’s White British and Bangladeshi adolescents. J Adolesc Heal 61:317–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.03.009

Stansfeld S, Haines MM, Head JA et al (2004) Ethnicity, social deprivation and psychological distress in adolescents school-based epidemiological study in east London. Br J Psychiatry 185:233–238

Bhui K, Lenguerrand E, Maynard MJ et al (2012) Does cultural integration explain a mental health advantage for adolescents? Int J Epidemiol 41:791–802. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys007

Connelly R, Platt L (2014) Cohort profile: UK Millennium Cohort Study (MCS). Int J Epidemiol 43:1719–1725. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu001

Ketende SC, Jones EM (2011) The Millennium Cohort Study: User Guide to Analysing MCS Data using STATA. Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education, University of London

Goodman R (1997) The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Goodman A, Goodman R (2009) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48:400–403. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181985068

Achenbach TM, Becker A, Döpfner M et al (2008) Multicultural assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology with ASEBA and SDQ instruments: research findings, applications, and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49:251–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01867.x

Galobardes B (2006) Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Heal 60:7–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.023531

Cutrona CE, Russell D (1987) The provisions of social relationships and adaption to stress. In: Jones H, Pearlman D (eds) Advances in personal relationships. A research annual 1. Jai Press Inc

Ipsos Mori (2017) Millennium Cohort Study Sixth Sweep (MCS6) Technical Report. Centre for Longitudinal Studies, UCL Institute of Education

Marmot M, Wilkinson RG (2005) The life course, the social gradient, and health. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson RG (eds) Social determinants of health. Oxford University Press, pp 54–77

McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T (2016) Mental health and Wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. NHS Digital, Leeds

Patalay P, Fitzsimons E (2018) Mental ill-health and wellbeing at age 14 - Initial findings from the Millennium Cohort Study Age 14 Survey. Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education, University of London, London

Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S et al (2012) Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 379:1641–1652. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4

Harding S, Read UM, Molaodi OR et al (2015) The Determinants of young Adult Social well-being and Health (DASH) study: diversity, psychosocial determinants and health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50:1173–1188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1047-9

Senior PA, Bhopal R (1994) Ethnicity as a variable in epidemiological research. BMJ 309:327–330. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.309.6950.327

Anand SS (1999) Using ethnicity as a classification variable in health research: perpetuating the myth of biological determinism, serving socio-political agendas, or making valuable contributions to medical sciences? Ethn Health 4:241–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557859998029

Dogra N, Singh SP, Svirydzenka N, Vostanis P (2012) Mental health problems in children and young people from minority ethnic groups: the need for targeted research. Br J Psychiatry 200:265–267. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.100982

Bhopal R (1997) Is research into ethnicity and health racist, unsound, or important science? BMJ 314:1751. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7096.1751

Schofield P, Das-Munshi J, Mathur R et al (2016) Does depression diagnosis and antidepressant prescribing vary by location? Analysis of ethnic density associations using a large primary-care dataset. Psychol Med 46:1321–1329. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002913

Jun J, Jivraj S, Taylor K (2020) Mental health and ethnic density among adolescents in England: a cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med 244:112569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112569

Wallace S, Nazroo J, Bécares L (2016) Cumulative effect of racial discrimination on the mental health of ethnic minorities in the United Kingdom. Am J Public Health 106:1294–1300. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303121

Li Y, Heath A (2020) Persisting disadvantages: a study of labour market dynamics of ethnic unemployment and earnings in the UK (2009–2015). J Ethn Migr Stud 46:857–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1539241

Kelly Y, Becares L, Nazroo J (2013) Associations between maternal experiences of racism and early child health and development: findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 67:35–41. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2011-200814

Edbrooke-Childs J, Newman R, Fleming I et al (2016) The association between ethnicity and care pathway for children with emotional problems in routinely collected child and adolescent mental health services data. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 25:539–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-015-0767-4

Goodman A, Patel V, Leon DA (2010) Why do British Indian children have an apparent mental health advantage? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51:1171–1183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02260.x

Memon A, Taylor K, Mohebati LM et al (2016) Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: a qualitative study in Southeast England. BMJ Open 6:e012337. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012337

Kersten P, Czuba K, McPherson K et al (2016) A systematic review of evidence for the psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Int J Behav Dev 40:64–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415570647

Platt L, Warwick R (2020) Are some ethnic groups more vulnerable to COVID-19 than others? The Institute for Fiscal Studies

Camara M, Bacigalupe G, Padilla P (2017) The role of social support in adolescents: are you helping me or stressing me out? Int J Adolesc Youth 22:123–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2013.875480

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the participants and researchers of the UK MCS, and to the CLS, UCL Institute of Education for use of these data, and to the UK Data Service for making them available.

Funding

GA is currently supported by an ESRC studentship (ES/P000703/1). JD is supported by the Health Foundation working together with the Academy of Medical Sciences, for a Clinician Scientist Fellowship, by the ESRC in relation to the SEP-MD study (ES/S002715/1), and by the King’s College London and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration South London (NIHR ARC South London) at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. SH and JD are partly supported by the Economic and Social Research Council Centre for Society and Mental Health at King’s College London [ES/S012567/1], and by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. SM is supported by UK Research and Innovation (MR-VO49879/1). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care, ESRC, UKRI, or King’s College London.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GA conducted the statistical analysis and wrote the paper. JD supervised drafting and development. SM, LB, and SH provided feedback and expert insights on the subject, supporting critical revision of the material to prepare for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

An End User Licence with the UK Data Service was agreed to access the data, and the research was approved by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine MSc Research Ethics Committee in 2017, reference 14337.

Consent to participate and for publication

As detailed within the Millennium Cohort Study Sixth Sweep Technical Report: ‘All adult respondents had to give informed consent in writing to take part in the survey themselves. For cohort members, parents were asked for their written consent to allow the interviewer to speak to the young person and ask for their consent to participate in each element (parents were not asked to consent of behalf of the young person). Interviewers were required to ensure that consent from the young person was as fully informed as possible’.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad, G., McManus, S., Bécares, L. et al. Explaining ethnic variations in adolescent mental health: a secondary analysis of the Millennium Cohort Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 57, 817–828 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02167-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02167-w