Abstract

Aim/hypothesis

Leisure-time physical activity can reduce the risk of Type 2 diabetes, but the potential effect of different types of physical activity is still uncertain. This study is to examine the relationship of occupational, commuting and leisure-time physical activity with the incidence of Type 2 diabetes.

Methods

We prospectively followed 6898 Finnish men and 7392 women of 35 to 64 years of age without a history of stroke, coronary heart disease, or diabetes at baseline. Hazards ratios of incidence of Type 2 diabetes were estimated by levels of occupational, commuting, and leisure-time physical activity.

Results

During a mean follow-up of 12 years, there were 373 incident cases of Type 2 diabetes. In both men and women combined, the hazards ratios of diabetes associated with light, moderate and active work were 1.00, 0.70 and 0.74 (p=0.020 for trend) after adjustment for confounding factors (age, study year, sex, systolic blood pressure, smoking, education, the two other types of physical activity and BMI). The multivariate-adjusted hazards ratios of diabetes with none, 1 to 29, and more than 30 min of walking or cycling to and from work were 1.00, 0.96, and 0.64 (p=0.048 for trend). The multivariate-adjusted hazards ratios of diabetes for low, moderate, high levels of leisure-time physical activity were 1.00, 0.67, and 0.61 (p=0.001 for trend); after additional adjustment for BMI, the hazards ratio was no longer significant.

Conclusions/interpretation

Moderate and high occupational, commuting or leisure-time physical activity independently and significantly reduces risk of Type 2 diabetes among the middle-aged general population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Physical activity has been advocated as one of the most important modifiable factors in the primary prevention of Type 2 diabetes [1]. A number of prospective studies have described that higher level of leisure-time physical activity is associated with a reduced risk of Type 2 diabetes [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. Two of these studies also found that the inverse association between walking and the risk of Type 2 diabetes was similar to that between vigorous leisure-time physical activity and diabetes [9, 11]. It is not clear whether occupational physical activity is also related to a reduced incidence of Type 2 diabetes. Daily commuting physical activity on foot or by bicycle as a single physical activity component has traditionally been one of the major forms of physical activity in some countries, such as Finland, Denmark, Netherlands and China, where many people walk or ride a bicycle to and from work [12, 13, 14, 15]. A few studies have suggested that daily cycling or walking to and from work is related to fewer cardiovascular risk factors [16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21], and reduces all-cause mortality [13]. Although many studies in western cultures indirectly measure commuting physical activity when asking about the frequency and duration of walking or cycling, no study addresses commuting physical activity as a single physical activity component in relation to the risk of Type 2 diabetes. The aim of this study is to examine whether occupation, commuting, or leisure-time physical activity is independently associated with reduced risk of Type 2 diabetes in a prospective cohort study.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

We carried out baseline surveys in two eastern Finnish provinces, North Karelia and Kuopio, and in the Turku-Loimaa region in southwestern Finland in 1982, 1987 and 1992. The survey was expanded to the Helsinki capital area in 1992. These surveys were conducted according to the ethical rules of the National Public Health Institute. The investigations were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In the three surveys, the sample included subjects who were 25 to 64 years of age. The 1982, 1987 and 1992 cohorts were combined in this analysis. The original random sample was stratified by sex and four equally large 10-year age groups (25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64) according to the WHO MONICA protocol [22, 23] and consisted of 21 630 subjects. The participation rate varied by year from 74% to 88% [24]. Our analysis includes participants of 35 to 64 years of age (16 670 samples) due to the very few cases of Type 2 diabetes in subjects aged 25–34 years during the follow-up. The final sample comprised 6898 men and 7392 women excluding subjects diagnosed with coronary heart disease or stroke (n=590), subjects with known diabetes (n=435) at baseline, and subjects with incomplete data on all required factors or on physical activity (n=1355).

Measurements

A self-administered questionnaire was sent to the participants to be completed at home. The questionnaire included questions on medical history, socioeconomic factors, physical activity and smoking habits. Education level, measured as the total number of school years, was divided into birth cohort specific tertiles. The participants were classified into two smoking categories: current smokers and non-smokers.

Physical activity included occupational, commuting, and leisure-time physical activity. A detailed description of the questions is presented elsewhere [25, 26], and questions constructed and evaluated previously [27]. The subjects reported their occupational physical activity according to the following three categories: (i) 'light' was physically very easy, sitting office work, e.g. secretary; (ii) 'moderate' was work including standing and walking, e.g. store assistant; (iii) 'active' was work including walking and lifting, or heavy manual labor, e.g. industrial work, farm work. The subjects were asked whether they walked, rode a bicycle, or used motorized transportation to and from work as well as the daily duration of this activity. The daily commuting return journey was categorized into three categories: (i) using motorized transportation, or no work (0 min of walking or cycling); (ii) walking or bicycling 1 to 29 min; (iii) walking or bicycling for more than 30 min. Self reported leisure-time physical activity was classified into three categories: (i) 'low' was defined as almost completely inactive, e.g. reading, watching TV, or doing some minor physical activity but not of moderate or high level; (ii) 'moderate' was doing some physical activity more than 4 h a week, e.g. walking, cycling, light gardening, fishing, hunting, but excluding travel to work; (iii) 'high' was performing vigorous physical activity more than 3 h a week, e.g. running, jogging, skiing, swimming, ball games, heavy gardening, or regular exercise or competitive sports several times a week.

At the study site, specially trained nurses measured height, weight, and blood pressure using a standardized protocol according to the WHO MONICA project [23]. Blood pressure was measured from the right arm of the participant who was seated for 5 min before the measurement and used a standard sphygmomanometer. Body weight of the subjects wearing usual light clothing without shoes was measured (±0.1 kg). Height was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm. Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (m). Obesity was defined as a BMI greater than 30.0 kg/m2.

Diagnosis of diabetes

We ascertained incident cases of diabetes from the National Hospital Discharge Register and the National Social Insurance Institution's Register. The National Hospital Discharge Register data were linked to the risk factor survey data with the unique identification numbers assigned to every resident of Finland. Antidiabetic drugs prescribed by a physician are free of charge in Finland subject to approval of a physician who reviews each case history. The physician confirms the diagnosis of diabetes on the basis of the World Health Organization criteria [28]. All patients receiving free medication (either oral antidiabetic agents or insulin) are entered into a register maintained by the Social Insurance Institution. The National Hospital Discharge Register has reported the codes for Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in Finland since 1987. Follow-up of each participant in our present analysis continued through the end of 1998 or until death. All new cases identified during the follow-up of this cohort had Type 2 diabetes.

Statistical analyses

SPSS for Windows 10.1 was used for statistical analysis. Differences in risk factors between groups with different levels of physical activity were tested using univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) after adjustment for age and study year. Logistic regression was used to compare differences in age- and study-year-adjusted prevalence of obesity and current smoking for activity groups.

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the effect of physical activity on the risk of Type 2 diabetes incidence. All analyses were adjusted for the following covariate: age, study year, education, systolic blood pressure, smoking, the other two types of physical activity, BMI, and for sex when analyses included both sexes combined. To further assess whether the effect differed between the sexes, we analysed the first levels of interaction between physical activity and sex for the risk of Type 2 diabetes. To examine the combined effect of all three types of activity level, we also estimated the multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios for the development of Type 2 diabetes by joint classifications of all three types of activity. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

There were 373 cases of Type 2 diabetes identified during a mean follow up period of 12 years. The major risk factors adjusted for age and study year are shown according to each level of occupational, commuting or leisure-time physical activity, respectively (Table 1). In general, older persons were less likely to walk or cycle to and from work or to be engaged in higher level of occupational or leisure-time physical activity. After adjustment for age and study year, both commuting and leisure-time physical activity were significantly and inversely associated with the mean values of BMI, blood pressure, and the prevalence of obesity and current smoking in both sexes. For occupational activity, however, women who were physically active had the highest mean values of BMI, systolic blood pressure, and prevalence of obesity than women with light or moderate occupational activity.

We assessed the interaction between study year and occupation, commuting and leisure-time physical activity on the risk of Type 2 diabetes. Because no significant interaction between study year and physical activity was found, we pooled the data for all three study years for further analysis. We also evaluated whether the effect of physical activity on the risk of Type 2 diabetes was different between men and women. Since the interaction between sex and physical activity on the risk of Type 2 diabetes was not statistically significant, men and women were combined in some analyses.

Occupational physical activity and risk of Type 2 diabetes

Table 2 shows the adjusted Cox hazards models of the risk of Type 2 diabetes for different levels of occupational physical activity for men, women and both sexes combined. Multivariate-adjusted (age, study year, systolic blood pressure, smoking, and education) relative risks of Type 2 diabetes decreased significantly with increasing occupational activity for both sexes. The hazard ratios associated with light, moderate and active work for risk of diabetes were 1.00, 0.63, 0.64 for men (p=0.012 for trend), and 1.00, 0.59, 0.77 for women (p=0.045 for trend), respectively. After further adjustment for commuting and leisure-time physical activity, this inverse association was still significant among men (p=0.033 for trend) but no longer significant among women. When both men and women were combined, occupational activity remained significantly and inversely associated with diabetes incidence after adjustment for sex and multivariate risk factors (p<0.001 for trend), additional adjustment for commuting and leisure-time physical activity (p=0.008), and further adjustment for BMI (the hazard ratios associated with light, moderate and active work were 1.00, 0.70 and 0.74, respectively, p=0.020 for trend).

Commuting physical activity and risk of Type 2 diabetes

An increase in daily time spent on walking or cycling to and from work was significantly and inversely associated with multivariate-adjusted relative risk of Type 2 diabetes in both sexes (p=0.052 for trend in men, p=0.003 for trend in women) (Table 3). The inverse relation did not appreciably change after adjustment for both occupational and leisure-time physical activity among women (p=0.025 for trend) but was no longer significant among men. When both sexes were combined, the inverse association also remained significant after adjustment for sex, multivariate risk factors, occupational and leisure-time physical activity, and BMI. The adjusted relative risks with 0, 1 to 29, and more than 30 min of walking or cycling to and from work were 1.00, 0.96, and 0.64, respectively (p=0.048 for trend). The risk of diabetes was the lowest among men and women who walked or cycled to and from work over 30 min daily.

Leisure-time physical activity and risk of Type 2 diabetes

The multivariate-adjusted relative risk of Type 2 diabetes decreased progressively with increasing levels of leisure-time physical activity among men (p=0.048 for trend) and women (p=0.006 for trend) (Table 4). This inverse association was also significant after further adjustment for occupational and commuting physical activity, but became non-significant after additional adjustment for BMI.

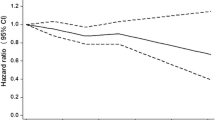

All three types of physical activity and risk of Type 2 diabetes

In multivariate analyses, we estimated independent and joint effects of all three types of physical activity on the risk of Type 2 diabetes (Fig. 1). We dichotomized all three types of physical activity at light versus moderate to high levels for occupational and leisure-time physical activity, and at a threshold of 30 min for commuting physical activity. In comparison with persons who reported light levels of occupational, commuting (<30 min) and leisure-time physical activity, subjects who reported all three types of moderate to high physical activity were at a 62% decreased risk for developing Type 2 diabetes (p<0.001 for trend). Using the same reference group, subjects who reported two types of moderate to high physical activity had 30% to 57% decreased risk and subjects who reported only one type of moderate to high physical activity had 22% to 27% decreased risk. The group with light occupational and leisure-time physical activity but over 30 minutes of commuting activity had a 85% reduced risk for diabetes, which could be due to the small sample size in this stratum (200 subjects) and only one case of incident Type 2 diabetes.

Relative risk of Type 2 diabetes according to different levels of occupational, commuting, and leisure-time physical activity. Adjusted for age, sex, study year, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, education, and BMI. The table below the figure gives the number of new cases of Type 2 diabetes and the sample sizes among the different physical activity group

Discussion

Our analysis addressed the association of physical activity with the risk of Type 2 diabetes. Moderate or vigorous activity at work, and moderate or high levels of leisure-time physical activity were associated with a reduced risk for Type 2 diabetes. Daily walking or cycling to and from work for more than 30 min was also significantly and inversely associated with risk of Type 2 diabetes. These associations were independent of age, systolic blood pressure, smoking, education, the other two types of physical activity and BMI. Simultaneously doing two or three types of moderate or high levels of occupational, commuting, and leisure-time physical activity was independently and significantly associated with lower risk of Type 2 diabetes than doing only one type of moderate or high physical activity.

We reported that moderate or vigorous occupational activity was separately and significantly associated with lower risk of diabetes among men and women after adjustment for commuting, leisure-time physical activity and other known risk factors. If this finding represents a causal relation, it is relevant to the prevention of Type 2 diabetes among working people, because the increase in computerization and mechanization has caused ever-increasing numbers of people to be sedentary for most of their working time during the last decades [29].

The association between walking or cycling to work and diabetes risk was greatest in people doing more than 30 min of the above activity, which supports the recommendation from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine [30]. This finding is important because daily activity of walking or cycling to work is a major source of total physical activity in some populations. In the Health Behavior Finnish Survey in 2000, 41% of people walked or cycled to and from work daily [14]. In urban China, more than 90% of people walk or cycle to and from work daily [15]. Several studies including the present analysis have shown that daily walking or cycling to and from work is inversely associated with BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, blood pressure, serum total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations and positively associated with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations [16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21]. One Danish study indicated that cycling to work was associated with lower all-cause mortality [13]. In many Western studies, commuting physical activity was indirectly measured by asking the participants the frequency and duration of their walking or bicycling. Our results emphasize the importance of separating physical activity during commuting as a single physical activity component from overall physical activity for the prevention of chronic diseases.

A number of prospective studies among specific populations of college alumni [2], nurses [3, 9], and male physicians [5, 11] in the United States, and among residents of the United Kingdom [7, 10] and Finland [8] have indicated that regular leisure-time physical activity is associated with decreased risk of Type 2 diabetes. Two of these studies among American nurses and male physicians also found that walking compared with vigorous leisure-time physical activity had the similar inverse association with the risk of Type 2 diabetes [9, 11]. Our study supports these previous findings and also expands types of regular physical activity including occupational activity and activity from daily walking or cycling to and from work. Simultaneously doing two or three types of moderate or high occupational, commuting, and leisure-time physical activity was associated with the lowest risk of Type 2 diabetes.

In our study, age, education, systolic blood pressure, sex, and BMI were associated with risk of Type 2 diabetes. When these confounding factors were entered into the models, the inverse association between physical activity and the risk of Type 2 diabetes was slightly attenuated. Overweight or obesity has been shown to be an important risk factor for Type 2 diabetes [31, 32]. Occupational, commuting, or leisure-time physical activity might reduce the risk of Type 2 diabetes indirectly through decreased body weight or improved body fat distribution. Overweight or obese people are less active than people of normal weight, and physical activity facilitates weight loss and weight maintenance [33].

Regular physical activity improves insulin sensitivity and also reduces other components of insulin resistance syndrome [10, 34]. A recent analysis from the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study showed that both vigorous and non-vigorous activities were associated with higher insulin sensitivity among 1467 men and women of 40 to 69 years of age [34]. The British Regional Study examined the role of serum insulin concentration and components of the insulin resistance syndrome in the relation between physical activity and the incidence of Type 2 diabetes among 5159 men of 40 to 59 years of age [10]. It showed that physical activity (including light and moderate levels) was significantly and inversely associated with serum insulin concentrations and with many of its components, and serum insulin concentrations and components of the insulin-resistance syndrome was a mediating factor in the relation between physical activity and the incidence of Type 2 diabetes. Recent clinical trials in China, Finland and the United States have shown that lifestyle-intervention (dietary modification and enhanced physical activity) reduced the risk of progressing from impaired glucose tolerance to Type 2 diabetes and also improved several CVD risk factors [35, 36, 37].

A limitation of our study was the self-report of physical activity. Using a questionnaire to assess habitual physical activity is crude and imprecise. Misclassification is inevitable and usually results in a biased estimate of the association of physical activity and risk of Type 2 diabetes. Another limitation was that we did not carry out a glucose tolerance test in the baseline and follow-up. Therefore, we could have missed some cases of asymptomatic diabetes although the clinical diagnosis of diabetes from the hospital discharge register and diet treatment register for those not using drugs avoided this potential under-diagnosis. This limitation of our study is likely to be independent of the physical activity, and thus, does not cause any bias for the outcome.

In conclusion, our study confirmed that moderate and higher levels of physical activity were associated with a lower risk of Type 2 diabetes. Moreover, we have provided evidence that not only leisure-time physical activity, but also occupational activity and daily activity from walking or cycling to and from work could be important especially for the prevention of Type 2 diabetes.

References

Tuomilehto J, Tuomilehto-Wolf E, Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Knowler WC (1997) Primary prevention in diabetes mellitus. In: Alberti KG, Zimmet P, DeFronzo RA, Keen H (eds) International textbook of diabetes mellitus, 2nd edn. Wiley, Chichester, pp 1799–1827

Helmrich SP, Ragland DR, Leung RW, Paffenbarger RS (1991) Physical activity and reduced occurrence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 325:147–152

Manson JE, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ et al. (1991) Physical activity and incidence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. Lancet 338:774–778

Schranz A, Tuomilehto J, Marti B, Jarrett RJ, Grabauskas V, Vassallo A (1991) Low physical activity and worsening of glucose tolerance: results from a 2-year follow-up of a population sample in Malta. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 11:127–136

Manson JE, Nathan DM, Krolewski AS, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hennekens CH (1992) A prospective study of exercise and incidence of diabetes among US male physicians. JAMA 268:63–67

Burchfiel CM, Sharp DS, Curb JD et al. (1995) Physical activity and incidence of diabetes: the Honolulu Heart Program. Am J Epidemiol 141:360–368

Perry IJ, Wannamethee SG, Walker MK, Thomson AG, Whincup PH, Shaper AG (1995) Prospective study of risk factors for development of non-insulin dependent diabetes in middle aged British men. BMJ 310:560–564

Haapanen N, Miilunpalo S, Vuori I, Oja P, Pasanen M (1997) Association of leisure time physical activity with the risk of coronary heart disease, hypertension and diabetes in middle-aged men and women. Int J Epidemiol 26:739–747

Hu FB, Sigal RJ, Rich-Edwards JW et al. (1999) Walking compared with vigorous physical activity and risk of type 2 diabetes in women: a prospective study. JAMA 282:1433–1439

Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Alberti KG (2000) Physical activity, metabolic factors, and the incidence of coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes. Arch Intern Med 160:2108–2116

Hu FB, Leitzmann MF, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rimm EB (2001) Physical activity and television watching in relation to risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus in men. Arch Intern Med 161:1542–1548

Hendriksen IJ (1996) The effect of commuter cycling on physical performance and on coronary heart disease risk factors. Doctoral Dissertation, Free University, Amsterdam

Andersen LB, Schnohr P, Schroll M, Hein HO (2000) All-cause mortality associated with physical activity during leisure time, work, sports, and cycling to work. Arch Intern Med 160:1621–1628

Helakorpi S, Uutela A, Prättälä R, Puska P (2000) Health behaviour and health among Finnish adult population, spring 2000. National Public Health Institute, Department of Epidemiology and Health Promotion, Helsinki

Hu G, Pekkarinen H, Hanninen O et al. (2002) Physical activity during leisure and commuting in Tianjin, China. Bulletin WHO 20:933–938

Hayashi T, Tsumura K, Suematsu C, Okada K, Fujii S, Endo G (1999) Walking to work and the risk for hypertension in men: the Osaka Health Survey. Ann Intern Med 131:21–26

Lahti-Koski M, Pietinen P, Mannisto S, Vartiainen E (2000) Trends in waist-to-hip ratio and its determinants in adults in Finland from 1987 to 1997. Am J Clin Nutr 72:1436–1444

Hu G, Pekkarinen H, Hanninen O, Tian H, Guo Z (2001) Relation between commuting, leisure time physical activity and serum lipids in a Chinese urban population. Ann Hum Biol 28:412–421

Hu G, Tian H (2001) A comparison of dietary and non-dietary factors of hypertension and normal blood pressure in a Chinese population. J Hum Hypertens 15:487–493

Hu G, Pekkarinen H, Hanninen O, Yu Z, Guo Z, Tian H (2002) Commuting, leisure-time physical activity, and cardiovascular risk factors in China. Med Sci Sports Exerc 34:234–238

Hu G, Pekkarinen H, Hanninen O, Tian H, Jin R (2002) Comparison of dietary and non-dietary risk factors in overweight and normal-weight Chinese adults. Br J Nutr 88:91–97

WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators (1988) The World Health Organization MONICA Project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): a major international collaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 41:105–114

Pajak A, Kuulasmaa K, Tuomilehto J, Ruokokoski E (1988) The WHO MONICA Project. Geographical variation in the major risk factors of coronary heart disease in men and women aged 35–64 years. World Health Stat Q 41:115–140

Vartiainen E, Jousilahti P, Alfthan G, Sundvall J, Pietinen P, Puska P (2000) Cardiovascular risk factor changes in Finland, 1972–1997. Int J Epidemiol 29:49–56

Tuomilehto J, Marti B, Salonen JT, Virtala E, Lahti T, Puska P (1987) Leisure-time physical activity is inversely related to risk factors for coronary heart disease in middle-aged Finnish men. Eur Heart J 8:1047–1055

Fogelholm M, Mannisto S, Vartiainen E, Pietinen P (1996) Determinants of energy balance and overweight in Finland 1982 and 1992. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 20:1097–1104

Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD et al. (1985) Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five-City Project. Am J Epidemiol 121:91–106

WHO Study Group on Diabetes Mellitus (1985) Diabetes mellitus: report of a WHO study group. WHO Technical Report Series No 727, World Health Organization, Geneva

Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J (2001) Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature 414:782–787

Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN et al. (1995) Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA 273:402–407

Chan JM, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC (1994) Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care 17:961–969

Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rotnitzky A, Manson JE (1995) Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Ann Intern Med 122:481–486

Blair SN (1993) Evidence for success of exercise in weight loss and control. Ann Intern Med 119:702–706

Mayer-Davis EJ, D'Agostino R Jr, Karter AJ et al. (1998) Intensity and amount of physical activity in relation to insulin sensitivity: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. JAMA 279:669–674

Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH et al. (1997) Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 20:537–544

Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG et al. (2001) Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 344:1343–1350

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group (2002) Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes with Lifestyle Intervention or Metformin. N Engl J Med 346:393–403

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Finnish Academy (grants 38387, 46558, 52342, 53585, 76502, 77618). We are grateful to Dr. A. Pankow for editing the language.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, G., Qiao, Q., Silventoinen, K. et al. Occupational, commuting, and leisure-time physical activity in relation to risk for Type 2 diabetes in middle-aged Finnish men and women. Diabetologia 46, 322–329 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-003-1031-x

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-003-1031-x