Abstract

Introduction

Major Trauma Centres (MTCs) should ideally have all key surgical specialities on site. This may not always be the case since trauma is only one factor influencing speciality location. The implications of this can only be understood when the demands on specific specialities are established and this is not well documented. We investigated surgical speciality demand by quantifying the frequency and urgency of surgical trauma interventions.

Patients and methods

Data on adult trauma admissions for a UK MTC were retrieved from the UK Trauma Audit and Research Network for a 2-year period and analysed to establish the frequency and urgency of surgical interventions.

Results

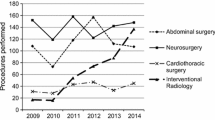

Of 1285 trauma patients with an ISS > 15 presenting in the study year period 713 (55.5%) required surgery. Neurosurgical (59.9%) and orthopaedic (55.1%) operations were most frequent. Cardiothoracic, general surgery, plastic surgery and maxillofacial operations were required infrequently. General surgery was commonly needed urgently, 45% within 4 h of MTC arrival. Urgency was also common in interventional radiology and vascular surgery. Cardiothoracic interventions were mainly urgent interventions (thoracotomy 1/3) and less urgent (rib fixation 2/3).

Discussion

Neurosurgery and orthopaedic surgery are key on-site trauma specialities and required frequently. General surgery, interventional radiology and cardiothoracic interventions are required less frequently but often urgently. This confirms a need for MTC on-site capability and possibly training to maintain competency in occasional trauma operators, particularly in general surgery. Maxillofacial surgery, ENT and urology are required neither frequently nor urgently and on-site presence may be less critical.

Conclusion

Demand for specific surgical specialities was reported in a cohort of UK trauma patients. This confirmed the need for rapid on-site capability in key specialities and highlights possible training requirements for occasional trauma operators in specialities with low frequency but high urgency.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Davenport RA, Tai N, West A, Bouamra O, Aylwin C, Woodford M, et al. A major trauma centre is a specialty hospital not a hospital of specialties. Br J Surg. 2010;97(1):109–17.

Jansen JO, Tai NR, Midwinter MJ. Planning trauma care services in the UK: surgical workforce development remains a challenge. BMJ. 2013;346:738.

Lane P. Trauma is not a surgical disease. Arch Emerg Med. 1989;6(2):85–9.

Acker S, Stovall R, Moore E, Patrick D, Burlew CC. Trauma remains a surgical disease from cradle to grave. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(2):219–25.

Galante JM, Phan HH, Wisner DH. Trauma surgery to acute care surgery: defining the paradigm shift. J Trauma. 2010;68(5):1024–31.

England RCoSo. Emergency surgery: standards for unscheduled care. Royal College of Surgeons of England, London 2011.

Surgeons CoT-ACo. Resources for optimal care of the injured patient. 6th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2014.

Major trauma. service delivery | Guidance and guidelines | NICE: NICE; 2018 [cited 2018 10/02]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng40.

England N (2013) NHS Standard contract for major trauma service. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/d15-major-trauma-0414.pdf.

Boudourakis LD, Wang TS, Roman SA, Desai R, Sosa JA. Evolution of the surgeon-volume, patient-outcome relationship. Ann Surg. 2009;250(1):159–65.

Chowdhury MM, Dagash H, Pierro A. A systematic review of the impact of volume of surgery and specialization on patient outcome. Br J Surg. 2007;94(2):145–61.

West JG, Cales RH, Gazzaniga AB. Impact of regionalization. The Orange County experience. Arch Surg. 1983;118(6):740–4.

Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, Maier RV. Effectiveness of state trauma systems in reducing injury-related mortality: a national evaluation. J Trauma. 2000;48(1):25–30

Patel HC, Bouamra O, Woodford M, King AT, Yates DW, Lecky FE Trends in head injury outcome from 1989 to 2003 and the effect of neurosurgical care: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;366(9496):1538–44.

Kehoe A, Smith JE, Edwards A, Yates D, Lecky F. The changing face of major trauma in the UK. BMJ 2015;5:6

Moya MD, Nirula R, Biffl W. Rib fixation: who, what, when? BMJ 2017;63:96

Rehn M, Davies G, Lockey D. A practical approach to resuscitative thoracotomy. Surgery. 2015;33(9):455–8.

Whittaker G, Norton J, Densley J, Bew D. Epidemiology of penetrating injuries in the United Kingdom: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2017;41:65–9.

Tai N, Bircher M. Trauma systems in England: a strategy for major trauma workforce generation and sustainability. Royal College of Surgeons of England, London 2014

National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Outcome. and Death. http://www.ncepod.org.uk/index.html. Accessed May 21 2018

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Quinn, P., Walton, B. & Lockey, D. An observational study evaluating the demand of major trauma on different surgical specialities in a UK Major Trauma Centre. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 46, 1137–1142 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-019-01075-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-019-01075-8