Abstract

Understanding fire regimes in the coastal region of the Pondoland center of plant endemism, (Eastern Cape, South Africa) is of critical importance, especially in areas where anthropogenic ignitions influence the fire regime. We characterized the fire regime (2007 to 2016) of Mkambati Nature Reserve (9200 ha) in terms of fire season, seasonality of fire-prone weather conditions, fire return interval (FRI), and influence of poaching-related ignitions. Fires were concentrated in winter when monthly fire danger weather index was highest. The mean FRI at Mkambati was <3 years, but varied according to vegetation type, and whether censoring (for open-ended FRIs) was applied. Mean estimated FRIs were 2.6 yr to 3.1 yr in the majority of grassland types, 5.6 yr to 8.0 yr in forests, and 9.0 yr to 44.4 yr in Themeda triandra Forssk. grasslands. Poachers, with the intention of attracting ungulates, are an important source of ignitions at Mkambati. Accordingly, FRIs were shorter (1.99 yr to 2.08 yr) in areas within 3 km of likely poacher entry points than in areas farther away (2.56 yr to 2.88 yr). Although all fires recorded at Mkambati during the study period were of anthropogenic origin, mean FRI still fell within the natural range reported for interior grasslands in South Africa.

Resumen

El entendimiento de los regimenes de fuego en la región costera del centro endémico de plantas llamado Pondoland (en el este del Cabo, en Sud África) es de importancia crítica, especialmente en áreas en las cuales las igniciones antropogénicas influencian este régimen. En este trabajo caracterizamos el régimen de fuegos (de 2007 a 2016) en la Reserva Natural de Mkambati (9200 ha) en términos de la estación de fuego, la estacionalidad de las condiciones meteorológicas proclives a fuego, el intervalo de retorno del fuego (FRI), y la influencia de las igniciones relacionadas con la caza furtiva. Los incendios estuvieron concentrados en el invierno cuando el indice meteorológico de peligro de incendios fue máximo. La media del intervalo de retorno del fuego (FRI) fue <3 años en Mkambati, aunque varió de acuerdo al tipo de vegetación y también cuando algún tipo de restricción fue aplicado al final de períodos de fuego más extendidos. Las medias estimadas de FRI fueron entre 2,6 años y 3,1 años en la mayoría de los tipos de pastizales, de entre 5,6 años a 8 años en bosques, y de 9,0 años a 44,4 años en pastizales de Themeda triandra Forssk. Los cazadores furtivos, con la intención de atraer a los ungulados, representan una fuente importante de igniciones en Mkambati. De acuerdo con esto, las FRI fueron más cortas (de 1,99 años a 2,08 años) en áreas dentro de los 3 km de los puntos de entrada de los cazadores furtivos que en áreas más alejadas (de 2,56 años a 2,88 años). Aunque todos los fuegos registrados en Mkambati durante el periodo de estudio fueron de origen antropogénico, la media del FRI todavía se encuentra dentro del rango natural reportado para los pastizales del interior de Sud África.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fire is an essential ecosystem process throughout many of the world’s terrestrial ecosystems (Bond et al. 2005) and particularly in Africa, “the fire continent” (Archibald et al. 2010b). However, in many of these ecosystems, fire regimes have been altered by anthropogenic interference (de Klerk et al. 2012). Fire regimes can be defined as the average fire conditions occurring over a defined period of time (Gill 1975, Brooks and Zouhar 2008, Chuvieco et al. 2008) in terms of frequency, seasonality, size, and type (Gill 1975), whereby individual fire events contribute to the overall fire regime (Van Wilgen et al. 2010). Dynamics that influence fire regimes, and thus the probability in time of a given area burning, include fuel, topography, weather conditions, ignition rates, and anthropogenic influences such as fire management effort (Archibald et al. 2009, Fernandes et al. 2012) and grazing regimes (Govender et al. 2006, Fuhlendorf et al. 2009, Ladbrook 2015).

In fire-prone ecosystems, managers need to understand historical fire regimes and the changes therein, as this gives insight into how the vegetation was shaped by fire, fuel accumulation rates (Bond et al. 2005, Kraaij et al. 2013a), and biodiversity responses to fire (Driscoll et al. 2010). Understanding fire regimes may furthermore assist mitigation of negative effects often associated with anthropogenic fire (Chuvieco et al. 2008), and aid with strategic planning for future fire management (Morgan et al. 2001). Human interference with fire (in the form of ignitions and suppression; Archibald et al. 2009, Fernandes et al. 2012) is often especially evident close to human habitation (Syphard et al. 2007, Archibald et al. 2009, Archibald et al. 2010b). The effects of anthropogenic ignitions on fire regimes are poorly understood (Bond and Parr 2010) but often occur at higher frequencies than natural ignitions (Brooks and Zouhar 2008) and pre-empt natural ignitions (Bond and Parr 2010). Anthropogenic ignitions may thus result in more frequent fires and additionally modify the seasonality, intensity, and size of fires (Chuvieco et al. 2008). On the contrary, human-induced suppression of fire and fragmentation of habitat may result in a lack of fires (Archibald et al. 2010b).

Grasslands account for a large portion of Earth’s fire-prone ecosystems and largely represent two so-called pyromes (similar to global syndromes of fire regimes, i.e., frequent-intense-large and frequent-cool-small; Archibald et al. 2013). In South Africa, grasslands compose almost one third of the land surface area (Mucina and Rutherford 2006, Bachinger et al. 2016). High seasonal rainfall in grasslands typically allows rapid fuel accumulation, resulting in some of the shortest fire return intervals (often <2 years) on Earth, which may be shortened further by anthropogenic ignitions (Archibald et al. 2010b, Bond and Parr 2010). In sourveld grasslands, in particular, fires tend to be more frequent later in the dry season (winter) when fire danger conditions are at their highest and grass curing has resulted in the accumulation of dead fuels (Van Wilgen et al. 2000). Large quantities of fine, flammable fuel make these sourveld highly adaptable to changing weather conditions, thus strongly influencing grassland fire regimes (Cheney and Sullivan 2008, Bond and Parr 2010).

Little is known about the fire ecology of the low-nutrient coastal sourveld of the Pondoland center of plant endemism along the east coast of South Africa (Van Wyk and Smith 2001). Current information suggests that fire regimes in these grasslands (Van Wilgen and Forsyth 2010) are comparable to those in other grassland types on the high-lying interior of South Africa (Mucina and Rutherford 2006), with fires occurring at one-year to four-year intervals, mostly in late winter when humidity is low, vegetation is dry, and wind speeds are high (Mucina and Rutherford 2006, Van Wilgen and Forsyth 2010). In order to characterize the fire regime of the low-nutrient coastal grasslands of Pondoland, we focused on Mkambati Nature Reserve (hereafter Mkambati) due to it being one of few areas of untransformed habitat in the region. Most fires at Mkambati are caused by anthropogenic ignitions associated with poaching (approximately 90%; personal communication, V. Mapiya, Mkambati Nature Reserve Manager, Eastern Cape, South Africa; Shackleton 1989; Van Wilgen and Forsyth 2010), which enabled an investigation of the effects of anthropogenic influences on the fire regime.

This research aimed to characterize the fire regime in the coastal sourveld grasslands of Mkambati over the past ten years in terms of frequency, seasonality, size, and potential importance of anthropogenic sources of ignition. In interpreting our findings, we considered whether fire frequency and season in this coastal sourveld system differs from that in the more extensive interior Highveld grassland systems of South Africa, and whether some of Pondoland’s unique biodiversity may be negatively affected by poachers’ influence on the fire regime.

Methods

Study Site

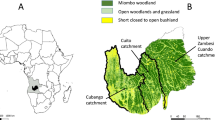

Mkambati (31°15′36″S, 29°59′24″E) is a small (9200 ha), fenced nature reserve situated on the southeast coast of South Africa, between Port Edward (30 km to the northeast) and Port St. Johns (59 km to the southeast) (Venter et al. 2014a). The reserve is managed by Eastern Cape Parks and Tourism Agency under a land claim settlement agreement with local communities (Kepe 2004). High annual rainfall (1200 mm) and mild temperatures (average of 18 °C in winter and 22 °C in summer) give rise to a mild subtropical climate with relatively high humidity (Shackleton et al. 1991). The vegetation is dominated by Pondoland-Ugu Sandstone Coastal Sourveld (Mucina et al. 2006) interspersed with patches of indigenous forest (scarp and southern coastal forest; Figure 1A; Shackleton 1989, Mucina and Rutherford 2006). The vegetation is nutrient poor resulting from the underlying geology and high levels of leaching (Mucina et al. 2006, Venter and Kalule-Sabiti 2016). Soils are composed of Mkambati sandstones of the broader Cape Supergroup (Fisher et al. 2013). Frequent fires resulted in a dynamic mosaic of recently burned and older grasses (Venter et al. 2014a). The vast majority of fires are ignited by poachers with the intention of attracting ungulates to areas in which they are easier to hunt (Shackleton 1989, Van Wilgen and Forsyth 2010). Apart from large herbivores at Mkambati, there are a number of rare, threatened, or endemic species of fauna and flora that are potentially affected by fire (Appendix 1). Mkambati management undertakes limited prescribed burning due to the high incidence of fires associated with poaching (Venter et al. 2014b). The spread of fire at Mkambati is limited by surrounding landscape features, in the form of natural boundaries (rivers) to the northeast and southwest, a well maintained firebreak inland to the west, and roads and indigenous forest within the reserve (Shackleton 1989).

(A) Vegetation types at Mkambati Nature Reserve (Shackleton 1989) and potential entry points used by poachers to access the reserve. (B) Mean fire return intervals (FRIs; calculated using the simplistic formula) per unique fire history polygon for the period 2007 to 2016 as denoted by shading (no shading represents the small areas that did not burned during the study period).

Fire Records

We compiled a spatial database of fires that occurred at Mkambati during the period January 2007 to August 2016. We used fire records (hand-drawn maps or Global Positioning System [GPS]-tracked fire boundaries) kept by reserve staff and fire boundaries that we digitized in GIS from Landsat TM imagery following methodology similar to that of Bowman et al. (2003), who used visual delimitation of fire scars to map fires from satellite imagery. When both reserve-derived and Land-sat-derived records were available for a fire, the Landsat-derived records were preferred as these were deemed to be more accurate. For some fires, Landsat images were not available due to interference of cloud cover (Bowman et al. 2003); we then used the reserve-derived records in these cases. Fire records (composed of a spatially referenced polygons and dates of fire) were assimilated in a GIS database using ArcGIS version 10.1 (Esri, Redlands, California, USA). For fire scars for which we had both reserve-derived and Landsat-derived records, we compared the areas burned according to the respective record types, using a paired t-test (Ashcroft and Pereira 2003). Using the same dataset, we also calculated the percentage error of omission for reserve-derived records (false negatives, i.e., burned areas missed by the reserve-derived records), and error of commission (false positives, i.e., where reserve-derived records over-mapped fires) (de Klerk et al. 2012).

Fire Size, Fire Season and Fire Danger Weather

We determined the relationship between number of fires and area burned on a monthly basis, using linear regression, as data conformed to a normal distribution. We used Statistica, version 13 (Dell Inc., Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA) for all statistical analyses. To explore fire-size distribution, we categorized fires into size classes (i.e., small <10 ha, medium ≥10 ha, large ≥100 ha, and very large ≥1000 ha). We explored the seasonality of fires by assessing the frequency distribution of fires (in terms of number of fires and area burned) across months. We furthermore assessed the seasonality of fire-prone weather conditions by calculating daily fire danger index (FDI) scores according to the South African Lowveld Model (Strydom and Savage 2013) for the study period. We used daily weather records for the town of Port Alfred (situated 30 km northeast of Mkambati) of maximum temperature, minimum relative humidity, rainfall, and average wind speed. The FDI scores were categorized as safe (FDI 0 to 20), moderate (21 to 45), dangerous (46 to 60), very dangerous (61 to 75), or extremely dangerous (75 to 100) (Meikle and Heine 1987). We explored the relationship between the seasonality of fires and the seasonality of fire-prone weather conditions by relating the monthly incidence of fires to average monthly FDI using two different regressions: number of fires vs. FDI and area burned vs. FDI. We also used regression to explore the relationship between fire size and FDI on the day of the fire.

To assess the likely effect of poaching as ignition source on the incidence of fires, we determined (in GIS) for each fire on record the distance between the fire-scar centroid and the nearest potential entry point where poachers are known to access the reserve (V. Mapiya, Mkambati Nature Reserve Manager, Eastern Cape, South Africa, personal communication; Figure 1A). We subsequently explored the relationship between the number of fires and the distance to likely poacher entry points.

Fire Return Interval

In order to assess fire return intervals (FRIs), we derived polygons of unique fire history (hereafter, “polygons”) by intersecting fire scars in GIS (Forsyth and Van Wilgen 2008, Kraaij et al. 2013a). To reduce noise in the dataset, polygons <1 ha in size were merged with neighboring polygons that had the longest shared boundary. Each polygon was characterized by zero or more fires, and polygons that had two or more fires thus experienced one or more complete FRI. The intervals before the first fires and after the last fires on record resulted in FRIs that were unknown. These open-ended FRIs were accounted for by means of censoring (Moritz et al. 2004) and are hereafter referred to as “censored,” as opposed to “complete” (i.e., did not require censoring) FRIs. We estimated mean FRIs using two methods. The first method calculated mean FRI using a simplistic formula

where y is the study period in years, b is the summed area of all the fires recorded over the study period, and a is the area over which fires were recorded (i.e., reserve size; Forsyth and Van Wilgen 2008, Kraaij 2010, Oliveira et al. 2012). Thus, this simplistic formula yields an area-based estimate of the length of time necessary for an area equal in size to the analysis area to burn (“fire rotation;” Romme 1980). In addition to its simplicity, this method does not require a fire frequency model (Oliveira et al. 2012), and is inclusive of area but not of censoring. The second method used maximum likelihood survival analysis by fitting a three-parameter Weibull function to the FRI distributions (Grissino-Mayer 2000). We accounted for area by weighing FRI records by polygon size (Fernandes et al. 2012). To account for polygons that never burned during the study period, we specified a constant of 10 (∼study period of 10 years) to be used for such double-censored FRIs. We calculated mean FRIs according to the above mentioned two methods for Mkambati as a whole, and for the respective vegetation types, to assess whether fire frequency differed among vegetation types. For this purpose, we simplified the vegetation categorization of Shackleton (1989) to be relevant to the accuracy and scale of fire scars, differentiating between (1) merged grasslands (including all Shackleton’s grassland types except Themeda triandra Forssk. grasslands, and including rocky outcrops and wetlands within these grasslands); (2) forests; and (3) Themeda triandra grasslands (henceforth referred to as Themeda grasslands, a grassland with dwarf stature in which fire is unlikely due to strong maritime influence; Figure 1A). To assess the effect of poacher influence on fire frequency, we calculated the mean FRI for merged grasslands (the predominant vegetation type) close to (within a 3 km buffer of) and away from (outside of a 3 km buffer of) likely poacher entry points. The 3 km buffer was based on the relationship established between the number of fire-scar centroids and distance to likely poacher entry points.

Results

Fire Records

Between January 2007 and August 2016, a total of 91 fires were recorded at Mkambati that burned an area of 27 510 ha. Of these records, 10 were Landsat-derived and not reserve-derived, 20 were reserve-derived and not Landsat-derived, and the remainder (61 fires) were both Landsat-derived and reserve-derived. For the latter set of records, the area burned according to reserve-derived records was significantly larger than the area burned according to Landsat-derived records (t = 2.28, P = 0.03, n = 61). Reserve-derived fire records showed a 20 % error in commission and a 9% error in omission when compared to the Landsat-derived images.

Fire Size, Fire Season, and Fire-Danger Weather

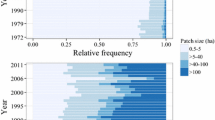

Individual fires at Mkambati during the study period varied in size from 6 ha to 2686 ha. Small (3 % of fires) and very large (5 % of fires) fires were uncommon, although these few very large fires accounted for 34% of the total area burned (Figure 2). The number of fires and area burned per month were significantly correlated (R2 = 0.88, P < 0.01, n = 12; Figure 2). Fire activity (when measured as number of fires or area burned) was concentrated in the winter months, (i.e., May to August, but with a dip in July; Figure 2). Very large fires (n = 5) almost exclusively occurred during these months. Fire-danger weather conditions also peaked during winter (May to August; Figure 2), with area burned per month being significantly and positively related to monthly mean FDI (R2 = 0.47, P < 0.05, n = 12). Accordingly, 57 % of fires occurred when FDI conditions were dangerous or higher. Average fire-danger weather conditions were moderate (mean FDI of 39) in the study area (Figure 2). Safe or moderate conditions occurred 66 % of the time, while very dangerous or extremely dangerous conditions occurred only 5 % of the time. The size of individual fires was not significantly related to FDI on the day of fire (R2 = 0.12, P = 0.27, n = 89).

Monthly distribution of fires of different size classes expressed as percentages of the total area burned and of the total number of fires recorded at Mkambati Nature Reserve during 2007 to 2016. Mean monthly fire danger index (FDI) score during the same period at the town of Port Edward is also shown.

Fire Return Interval

Intersection of fire scars produced 984 polygons of unique fire history (Figure 1B), with complete FRIs (areas that experienced at least two fires during the study season) recorded on 78 % of Mkambati. Of the FRIs recorded, 1911 (61%) were complete and 1246 (39%) censored. Estimates of mean FRI were influenced by the calculation method employed, with the Weibull function (applying censoring) consistently underestimating mean FRI when compared to the simplistic formula (Table 1). Mean FRI at Mkambati during the study period was estimated at ∼3 yr, and differed between vegetation types. Mean FRIs were 2.6 yr and 3.1 yr (Weibull and simplistic formula estimates, respectively) in the merged grasslands, 5.6 yr and 8.0 yr in forests, and 9.1 yr and 44.4 yr in the Themeda grasslands. Variance in estimates of mean FRI was higher for vegetation types for which a large percentage of the FRIs was censored (i.e., forests and Themeda grasslands).

Of the fires on the reserve, 69% of the fire-scar centroids occurred close to (within 3 km of) likely poacher entry points (Figure 3). Mean FRIs in areas close to likely poacher entry points were shorter (2.0 yr and 2.8 yr for Weibull and simplistic formula estimates, respectively) than those farther away from likely poacher entry points (2.6 yr and 2.9 yr, Figure 1B). Weibull-derived FRIs differed significantly between these two areas (no overlap in 95% confidence intervals; Table 1).

Distances from likely poacher entry points to fire-scar centroids (Figure 1) at Mkambati Nature Reserve between January 2007 and August 2016.

Discussion

Fire Size and Fire Records

Fires at Mkambati ranged in size from 6 ha to 2686 ha, which is small in relation to some grassland fires elsewhere in the world that ranged up to 400 000 ha (Bird et al. 2012, Ladbrook 2015). The finding that a smaller number of large fires (i.e., fires <1000 ha at Mkambati) contributed substantially to the total area burned on record has been observed in various ecosystems globally, including mediterranean-climate shrublands and grasslands (Forsyth and Van Wilgen 2008, Archibald et al. 2010a, Moreira et al. 2011, Kraaij et al. 2013a). The difference in area burned between Landsat-derived and reserve-derived records show the importance of using both record sources in conjunction with one another to facilitate the upkeep of comprehensive and accurate fire records. The level of accuracy attained in our study in deriving fire scars from Landsat imagery, especially in merged grasslands, is comparable to that attained by other studies in the savannas of northern Australia (Russell-Smith et al. 2003) and across vegetation types in Nevada, United States (Kolden and Weisberg 2007).

Seasonality of Fires and Fire Danger Weather

The fire season at Mkambati was from May to August (the dry season), during which time FDI was highest (average FDI >40). Fire season in these coastal grasslands thus mirror that of other grasslands in South Africa (Archibald et al. 2010a). Within the winter season, the number of fires and area burned at Mkambati peaked in June, after which the number of fires declined, suggesting that poachers set fires early in winter when grasses first die off. These fires stimulate new grass growth with elevated crude protein content (8.6 % compared to 4.6 % in more moribund vegetation; Shackleton 1989), thereby attracting ungulates to feed in these areas. The second peak in area burned during August through September (which is not reflected in number of fires) is likely explained by fewer but larger fires that are able to spread under high fire-danger weather conditions still prevailing during these months, and possibly some prescribed burns undertaken by management towards the end of the dry season.

Fire Return Intervals

Fire return intervals at Mkambati of approximately three years (<3 yr in the merged grasslands, which are representative of approximately 80 % of the reserve) are within the range (1 yr to 4 yr) reported for other grasslands in South Africa (Mucina et al. 2006). Variance in estimates of mean FRI was greater when high levels of censoring were applied, as found in other studies (Fernandes et al. 2012, Kraaij et al. 2013a). For Mkambati as a whole and for the merged grasslands, the level of censoring applied and the variance in estimates obtained of mean FRI were low, suggesting that the time series (study period) was sufficient to yield reasonable estimates of mean fire frequency. Accordingly, the two methods used for FRI estimation yielded comparable results for the merged grasslands. However, greater uncertainty was associated with the estimates of mean FRI derived for forests and Themeda grasslands. Here, greater levels of censoring were applied (including double-censoring) and FRIs were longer relative to the length of the time series studied. For these vegetation types, the estimates of mean FRI produced by the simplistic formula are considered to be more reliable. Estimates of mean FRI in vegetation types that do not experience regular fire could be refined if time series data were extended, emphasizing the need for comprehensive long-term fire records.

The other vegetation types at Mkambati (i.e., forests and Themeda grasslands) tend to burn much less frequently (>5 yr), most likely as a result of localized climatic conditions and different fuel characteristics. Grass fuels are characterized by loosely packed fine fuels, whereas forests have coarser fuels with higher fuel moisture contents (Hoffmann et al. 2012). Being situated along the coast, the Themeda grasslands are influenced by salt spray and wind from the ocean, causing cooler, moister conditions and stunted plant growth form, which likely account for the extended FRIs (Shackleton 1989).

It has been proposed that rigid fire regimes will not provide for the needs of a wide variety of fauna and flora, but instead that FRIs should be varied in space and time (pyrodiversity) to maintain higher levels of biodiversity (Parr and Andersen 2006). Within Mkambati, FRIs were not evenly distributed, with mean FRIs being significantly shorter close to likely poacher entry points than farther away. Differences in fire frequency between areas experiencing more and fewer poacher ignitions may provide pyrodiversity within Mkambati, allowing for a greater suite of biodiversity to persist in a small area. In the grasslands of Mpumalanga, South Africa, more frequent fires in fire breaks than in the adjacent matrix were found to have no negative effects on plant diversity unless the areas had been previously disturbed (Bachinger et al. 2016). We did not investigate the effects of pyrodiversity on biodiversity at Mkambati, but our findings in terms of differential FRIs across the reserve provide a basis for future research into this aspect.

Effects of Poaching and Implications for Management

It is clear from this study and others (Shackleton 1989, Oneka 1990, Veblen et al. 2000, Bowman et al. 2011, Archibald et al. 2012) that fire regimes may be significantly affected by anthropogenic influences. At Murchison Falls National Park, Uganda, poachers set fires outside the reserve with the intention of drawing animals outside of the protected area where they could be easily poached (Oneka 1990); whereas at Mkambati, fires were set inside of the reserve boundary for a similar purpose. Fires were most commonly set in areas that posed a low risk to poachers such as close to entry points and far away from the reserve’s law enforcement and infrastructure. The larger number of fire-scar centroids situated near the likely poacher entry points is indicative of a larger number of smaller fires in these areas. Similarly, in Australian savanna, a finer scale mosaic of burned and unburned areas was evident closer to human settlement (Bowman et al. 2004).

In order to formulate appropriate fire management guidelines (i.e., when fires should be suppressed or allowed to burn), an understanding of anthropogenic influences on the fire regime and of the potential ecological effects of untimely fires is required. To facilitate adaptive management of fire for biodiversity conservation, thresholds may be formulated outlining ecologically acceptable limits of variation (pyrodiversity; Van Wilgen et al. 2011). Such thresholds typically relate to ecological responses of biota to fire (e.g., post-fire recruitment or breeding success; Van Wilgen et al. 2011, Kraaij et al. 2013b). Mkambati represents the Pondoland center of plant endemism (Van Wyk and Smith 2001) and contains various threatened or endemic species of fauna and flora potentially affected by fire (Appendix 1). We considered how knowledge of these species’ ecology should be used to inform thresholds for the study area related to fire frequency, fire season, fire size, and interactions between fire and herbivory (Appendix 1; cf. Van Wilgen et al. 2011 and Kraaij et al. 2013b). This exercise also highlighted priorities for future research on biological responses to fire. In addition to consideration of threatened and endemic species, fire management at Mkambati also has to take account of species important for resource utilization (such as Cymbopogon validus Stapf [Stapf] ex Burtt Davy used for thatching by local communities; Kepe 2005), and interactions between fire and herbivory. The latter has implications for the availability and quality of forage and thus the performance of ungulates, the availability of fuels, fire frequency and intensity, and habitat condition (Venter et al. 2014a).

Conclusion

It is clear that a number of ecological factors need to be considered when evaluating past management and recommending appropriate future management of fire in protected areas. We have made a start by (1) establishing that past fire regimes at Mkambati broadly fell within ranges deemed natural for other grassland systems in South Africa, and (2) providing a fire history to underpin evaluations of the effects of different past fire frequencies on biota of the Pondoland center of plant endemism. Similar approaches may be used to develop and refine thresholds for fire management more generally in the context of protected area management (cf. Van Wilgen et al. 2011). Establishing links between fire interventions and biodiversity outcomes is particularly important in small, fenced reserves experiencing substantial anthropogenic influence.

Literature Cited

Archibald, S., C.E. Lehmann, J.L. Gómez-Dans, and R.A. Bradstock. 2013. Defining pyromes and global syndromes of fire regimes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110: 6442–6447. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211466110

Archibald, S., A. Nickless, N. Govender, R. Scholes, and V. Lehsten. 2010a. Climate and the inter-annual variability of fire in southern Africa: a meta-analysis using long-term field data and satellite-derived burnt area data. Global Ecology and Biogeography 19: 794–809. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00568.x

Archibald, S., D.P. Roy, B. Van Wilgen, and R.J. Scholes. 2009. What limits fire? An examination of drivers of burnt area in southern Africa. Global Change Biology 15: 613–630. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01754.x

Archibald, S., R. Scholes, D. Roy, G. Roberts, and L. Boschetti. 2010b. Southern African fire regimes as revealed by remote sensing. International Journal of Wildland Fire 19: 861–878. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/WF10008

Archibald, S., A.C. Staver, and S.A. Levin. 2012. Evolution of human-driven fire regimes in Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109: 847–852. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1118648109

Ashcroft, S., and C. Pereira. 2003. Practical statistics for the biological sciences. Macmillan Publishers, London, England, United Kingdom.

Bachinger, L.M., L.R. Brown, and M.W. Van Rooyen. 2016. The effects of fire-breaks on plant diversity and species composition in the grasslands of the Loskop Dam Nature Reserve, South Africa. African Journal of Range & Forage Science 33: 21–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.2989/10220119.2015.1088574

Bird, R.B., B.F. Codding, P.G. Kauhanen, and D.W. Bird. 2012. Aboriginal hunting buffers climate-driven fire-size variability in Australia’s spinifex grasslands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109: 10287–10292. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1204585109

Bond, W.J., and C.L. Parr. 2010. Beyond the forest edge: ecology, diversity and conservation of the grassy biomes. Biological Conservation 143: 2395–2404. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2009.12.012

Bond, W.J., F.I. Woodward, and G.F. Midgley. 2005. The global distribution of ecosystems in a world without fire. New Phytologist 165: 525–538. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01252.x

Bowman, D., Y. Zhang, A. Walsh, and R. Williams. 2003. Experimental comparison of four remote sensing techniques to map tropical savanna fire-scars using Landsat-TM imagery. International Journal of Wildland Fire 12: 341–348. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/WF03030

Bowman, D.M., J. Balch, P. Artaxo, W.J. Bond, M.A. Cochrane, C.M. D’Antonio, R. Defries, F.H. Johnston, J.E. Keeley, and M.A. Krawchuk. 2011. The human dimension of fire regimes on Earth. Journal of Biogeography 38: 2223–2236. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02595.x

Bowman, D.M., A. Walsh, and L. Prior. 2004. Landscape analysis of Aboriginal fire management in Central Arnhem Land, north Australia. Journal of Biogeography 31: 207–223. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0305-0270.2003.00997.x

Brooks, M.L., and K. Zouhar. 2008. Plant invasions and fire regimes. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on flora. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 6, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Cheney, P., and A. Sullivan. 2008. Grassfires: fuel, weather and fire behaviour. CSIRO Publishing, Clayton, Victoria, Australia.

Chuvieco, E., L. Giglio, and C. Justice. 2008. Global characterization of fire activity: toward defining fire regimes from Earth observation data. Global Change Biology 14: 1488–1502. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01585.x

De Klerk, H.M., A.M. Wilson, and K. Steenkamp. 2012. Evaluation of satellite-derived burned area products for the fynbos, a Mediterranean shrubland. International Journal of Wildland Fire 21: 36–47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/WF11002

Dippenaar-Schoeman, A.S., M. Hamer, and C.R. Haddad. 2011. Spiders (Arachnida: Araneae) of the vegetation layer of the Mkambati Nature Reserve, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Koedoe 53: 1–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/koedoe.v53i1.1058

Driscoll, D.A., D.B. Lindenmayer, A.F. Bennett, M. Bode, R.A. Bradstock, G.J. Cary, M.F. Clarke, N. Dexter, R. Fensham, and G. Friend. 2010. Fire management for biodiversity conservation: key research questions and our capacity to answer them. Biological Conservation 143: 1928–1939. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.05.026

Du Preez, L., and V. Carruthers. 2009. A complete guide to the frogs of southern Africa. Randomhouse Struik, Cape Town, South Africa, Africa.

Fernandes, P.M., C. Loureiro, M. Magalhães, P. Ferreira, and M. Fernandes. 2012. Fuel age, weather and burn probability in Portugal. International Journal of Wildland Fire 21: 380–384. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/WF10063

Fisher, E.C., R. Albert, G. Botha, H.C. Cawthra, I. Esteban, J. Harris, Z. Jacobs, A. Jerardino, C.W. Marean, and F.H. Neumann. 2013. Archaeological reconnaissance for middle stone age sites along the Pondoland Coast, South Africa. PaleoAnthropology 1: 104–137.

Forsyth, G.G., and B.W. Van Wilgen. 2008. The recent fire history of the Table Mountain National Park and implications for fire management. Koedoe 50: 3–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/koedoe.v50i1.134

Fuhlendorf, S.D., D.M. Engle, J. Kerby, and R. Hamilton. 2009. Pyric herbivory: rewilding landscapes through the recoupling of fire and grazing. Conservation Biology 23: 588–598. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01139.x

Gill, A.M. 1975. Fire and the Australian flora: a review. Australian Forestry 38: 4–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00049158.1975.10675618

Govender, N., W.S. Trollope, and B.W. Van Wilgen. 2006. The effect of fire season, fire frequency, rainfall and management on fire intensity in savanna vegetation in South Africa. Journal of Applied Ecology 43: 748–758. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01184.x

Grissino-Mayer, H.D. 2000. Modeling fire interval data from the American Southwest with the Weibull distribution. International Journal of Wildland Fire 9: 37–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/WF99004

Hamer, M.L., and R. Slotow. 2017. A conservation assessment of the terrestrial invertebrate fauna of Mkambati Nature Reserve in the Pondoland Centre of Endemism. Koedoe: 59: 1–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/koedoe.v59i1.1428

Hoffmann, W.A., S.Y. Jaconis, K.L. Mckinley, E.L. Geiger, S.G. Gotsch, and A.C. Franco. 2012. Fuels or microclimate? Understanding the drivers of fire feedbacks at savanna-forest boundaries. Austral Ecology 37: 634–643. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2011.02324.x

Kepe, T. 2004. Land restitution and biodiversity conservation in South Africa: the case of Mkambati, Eastern Cape Province. Canadian Journal of African Studies 38: 688–704.

Kepe, T. 2005. Grasslands ablaze: vegetation burning by rural people in Pondoland, South Africa. South African Geographical Journal 87: 10–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2005.9713821

Kolden, C., and P. Weisberg. 2007. Assessing accuracy of manually-mapped wildfire perimeters in topographically dissected areas. Fire Ecology 3: 22–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0301022

Kraaij, T. 2010. Changing the fire management regime in the renosterveld and lowland fynbos of the Bontebok National Park. South African Journal of Botany 76: 550–557. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2010.04.008

Kraaij, T., J.A. Baard, R.M. Cowling, B.W. Van Wilgen, and S. Das. 2013a. Historical fire regimes in a poorly understood, fire-prone ecosystem: eastern coastal fynbos. International Journal of Wildland Fire 22: 277–287. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/WF11163

Kraaij, T., R.M. Cowling, and B.W. Van Wilgen. 2013b. Fire regimes in eastern coastal fynbos: imperatives and thresholds in managing for diversity. Koedoe 55: 1–9.

Ladbrook, M. 2015. Spatial and temporal patterns (1973–2012) of bushfire in an arid to semi-arid region of Western Australia. Thesis, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Western Australia.

Masterson, G.P., B. Maritz, and G.J. Alexander. 2008. Effect of fire history and vegetation structure on herpetofauna in a South African grassland. Applied Herpetology 5: 129–143. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/157075408784648781

Meikle, S., and J. Heine. 1987. A fire danger index system for the Transvaal Lowveld and adjoining escarpment areas. South African Forestry Journal 143: 55–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00382167.1987.9630304

Moreira, F., O. Viedma, M. Arianoutsou, T. Curt, N. Koutsias, E. Rigolot, A. Barbati, P. Corona, P. Vaz, and G. Xanthopoulos. 2011. Landscape-wildfire interactions in southern Europe: implications for landscape management. Journal of Environmental Management 92: 2389–2402. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.06.028

Morgan, P., C.C. Hardy, T.W. Swetnam, M.G. Rollins, and D.G. Long. 2001. Mapping fire regimes across time and space: understanding coarse and fine-scale fire patterns. International Journal of Wildland Fire 10: 329–342. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/WF01032

Moritz, M.A., J.E. Keeley, E.A. Johnson, and A.A. Schaffner. 2004. Testing a basic assumption of shrubland fire management: how important is fuel age? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2: 67–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2004)002[0067:TABAOS]2.0.CO;2

Mucina, L., D.B. Hoare, M.C. Lötter, P.J. Du Preez, M.C. Rutherford, C.R. Scott-Shaw, G.J. Bredenkamp, L.W. Powrie, L. Scott, K.G.T. Camp, S.S. Cilliers, H. Bezuidenhout, T.H. Mostert, S.J. Siebert, P.J.D. Winter, J.E. Burrows, L. Dobson, R.A. Ward, M. Stalmans, E.G.H. Oliver, F. Siebert, E. Schmidt, K. Kobisi, and L. Kose. 2006. Grassland biome. Pages 348–437 in: L. Mucina and M.C. Rutherford, editors. The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa.

Mucina, L., and M.C. Rutherford, editors. 2006. The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa.

Mucina, L., C.R. Scott-Shaw, M.C. Rutherford, K.G.T. Camp, W.S. Matthews, L.W. Powrie, and D.B. Hoare. 2006. Indian Ocean Coastal Belt. Pages 568–583 in: L. Mucina and M.C. Rutherford, editors. The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa.

Oliveira, S.L., J.M. Pereira, and J.M. Carreiras. 2012. Fire frequency analysis in Portugal (1975–2005), using Landsat-based burnt area maps. International Journal of Wildland Fire 21: 48–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/WF10131

Oneka, M. 1990. Poaching in Murchison Falls National Park, Uganda. Pages 147–151 in: H. Svobodova, editor. Proceedings of the symposium—cultural aspects of landscape. International Association for Landscape Ecology, 28–30 June 1990, Baarn, The Netherlands.

Parr, C.L., and A.N. Andersen. 2006. Patch mosaic burning for biodiversity conservation: a critique of the pyrodiversity paradigm. Conservation Biology 20: 1610–1619. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00492.x

Raimondo, D., L. Von Staden, W. Foden, J.E. Victor, N.A. Helme, R.C. Turner, D. Kamundi, and P. Manyama. 2015. National assessment: Red List of South African plants, version 2015.1. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa.

Rebelo, T. 1995. Proteas: a field guide to the proteas of southern Africa. Fernwood Press, Cape Town, South Africa.

Romme, W. 1980. Fire history terminology: report of the ad hoc committee. Pages 135–137 in: M.A. Stokes and J.H. Dieterich, editors. Proceedings of the fire history workshop. USDA Forestry Service General Technical Report RM-81, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Russell-Smith, J., C. Yates, A. Edwards, G.E. Allan, G.D. Cook, P. Cooke, R. Craig, B. Heath, and R. Smith. 2003. Contemporary fire regimes of northern Australia, 1997–2001: change since Aboriginal occupancy, challenges for sustainable management. International Journal of Wildland Fire 12: 283–297. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/WF03015

Shackleton, C., J. Granger, B. Mckenzie, and M. Mentis. 1991. Multivariate analysis of coastal grasslands at Mkambati Game Reserve, north-eastern Pondoland, Transkei. Bothalia 21: 91–107. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/abc.v21i1.869

Shackleton, C.M. 1989. An ecological survey of a select area of Pondoland sourveld with emphasis on its response to the management practices of burning and grazing. Thesis, University of Transkei, Tipini, Mthatha, South Africa.

South African Frog Re-Assessment Group (SA-Frog). 2010. Breviceps bagginsi. The IUCN Red list of threatened species. <https://doi.org/www.iucnredlist.org/details/57713/0>. Accessed 5 January 2017.

Strydom, S., and M.J. Savage. 2013. A near real-time fire danger index measurement system. Pages 110–113 in: Proceedings of the 29th annual conference—towards quantifying and qualifying the Earth’s atmosphere. South African Society for Atmospheric Sciences, 26–27 September 2013, Durban, South Africa.

Syphard, A.D., V.C. Radeloff, J.E. Keeley, T.J. Hawbaker, M.K. Clayton, S.I. Stewart, and R.B. Hammer. 2007. Human influence on California fire regimes. Ecological Applications 17: 1388–1402. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/06-1128.1

Van Wilgen, B., H. Biggs, S. O’Regan, and N. Mare. 2000. Fire history of the savanna ecosystems in the Kruger National Park, South Africa, between 1941 and 1996. South African Journal of Science 96: 167–178.

Van Wilgen, B.W., and G.G. Forsyth. 2010. Fire management of the ecosystems of the wild coast, Eastern Cape Province. Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Stellenbosch, South Africa.

Van Wilgen, B.W., G.G. Forsyth, H. De Klerk, S. Das, S. Khuluse, and P. Schmitz. 2010. Fire management in mediterranean-climate shrublands: a case study from the Cape fynbos, South Africa. Journal of Applied Ecology 47: 631–638. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01800.x

Van Wilgen, B.W., N. Govender, G.G. Forsyth, and T. Kraaij. 2011. Towards adaptive fire management for biodiversity conservation: experience in South African National Parks. Koedoe 53: 96–104. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/koedoe.v53i2.982

Van Wyk, A.E., and G.F. Smith. 2001. Regions of floristic endemism in southern Africa: a review with emphasis on succulents. Umdaus Press, Pretoria, South Africa.

Veblen, T.T., T. Kitzberger, and J. Donnegan. 2000. Climatic and human influences on fire regimes in ponderosa pine forests in the Colorado Front Range. Ecological Applications 10: 1178–1195. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1178:CAHIOF]2.0.CO;2

Venter, J.A., and W. Conradie. 2015. A checklist of the reptiles and amphibians found in protected areas along the South African Wild Coast, with notes on conservation implications. Koedoe 57: 1–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/koedoe.v57i1.1247

Venter, J.A., and M.J. Kalule-Sabiti. 2016. The diet composition of large herbivores in Mkambati Nature Reserve, Eastern Cape, South Africa. African Journal of Wildlife Research 46: 49–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.3957/056.046.0049

Venter, J.A., J. Nabe-Nielsen, H.H. Prins, and R. Slotow. 2014a. Forage patch use by grazing herbivores in a South African grazing ecosystem. Acta Theriologica 59: 457–466. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13364-014-0184-y

Venter, J.A., H.H. Prins, D.A. Balfour, R. Slotow, and M. Hayward. 2014b. Reconstructing grazer assemblages for protected area restoration. PLoS ONE 9: e90900. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090900

Acknowledgements

We thank the Nelson Mandela University and Fairfield Tours for funding this study; J. Baard (South African National Parks) for assistance with analyses of fire return intervals in GIS; W. Oosthuizen (https://doi.org/www.firehawk.co.za) for assistance with fire danger calculations; and the Agricultural Research Council for supplying weather data for Port Edward. Suggestions of anonymous reviewers enabled improvement of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brooke, C.F., Kraaij, T. & Venter, J.A. Characterizing a Poacher-Driven Fire Regime in Low-Nutrient Coastal Grasslands of Pondoland, South Africa. fire ecol 14, 1–16 (2018). https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.140101016

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.140101016