Abstract

Researchers in cognitive and forensic psychology have long been interested in the impact of individual differences on eyewitness memory. The sex of the eyewitness is one such factor, with a body of research spanning over 50 years that has sought to determine if and how eyewitness memory differs between males and females. This research has significant implications across the criminal justice system, particularly in the context of gendered issues such as sexual assault. However, the findings have been inconsistent, and there is still a lack of consensus across the literature. A scoping review and analysis of the literature was performed to examine the available evidence regarding whether sex differences in eyewitness memory exist, what explanations have been proposed for any differences found, and how this research has been conducted. Through a strategic search of seven databases, 22 relevant articles were found and reviewed. Results demonstrated that despite the mixed nature of the methodologies and findings, the research suggests that neither males nor females have superior performance in the total amount of accurate information reported, but rather that females may have better memory for person-related details while males may perform better for details related to the surrounding environment. There was also consistent evidence for the own-gender bias. There was some consensus that differences in selective attention between males and females may underlie these sex differences in eyewitness memory. However, none of the studies directly tested this suggested attentional factor, and thus future research is needed to investigate this using a more systematic and empirical approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite advances in DNA analysis, there is still a significant reliance on eyewitness memory as a critical form of evidence within the criminal justice system. Eyewitness memory is utilised in numerous ways within these settings, such as providing witness statements and information to law enforcement, identifying suspects, and giving eyewitness testimony during judicial proceedings. Errors or omissions in eyewitness memory can thus have significant implications, from confounding police investigations to the wrongful conviction of innocent people, or even to the lack of conviction of guilty people. For instance, according to data from the USA, 69% of DNA-exonerated cases were wrongfully convicted as a direct result of memory errors and misidentification by eyewitnesses (Innocence Project, 2020). Given the significance of its impact on personal and community welfare, understanding the individual differences, such as the sex or gender of the eyewitness, that may influence the accuracy of eyewitness memory is thus of continuing relevance.

Following the renewed interest in witness memory research during the 1970s, the topic of sex differences became a focus of investigation, with a sub-set of literature developing across the 1980s and 1990s in particular. The findings from this research were largely inconsistent, however, and consequently little consensus was achieved (Areh, 2011). This focus on sex or gender differences seemed to fade for a period following this with few studies published, perhaps due to the inconclusive outcomes of the earlier research. However, interest has revived in recent years, corresponding with the current salience of social issues related to gendered crime. For instance, socio-political movements, such as the #MeToo movement that rose to prominence in 2017 (Levy & Mattsson, 2020), as well as some related high-profile court cases, have brought significant attention to gendered issues such as sexual assault and domestic violence. This also extends to associated debate related to the veracity and reliability of the memories of the males and females involved. The effects of this have been seen across the world, with the number of sexual crimes reported to police increasing by 10% across 30 countries within the first 6 months of the #MeToo movement alone (Levy & Mattsson, 2020). Sexual assault and domestic violence are both heavily gendered crimes, with the majority of offences committed by male perpetrators against female victims (Tidmarsh & Hamilton, 2020; Wilcox et al., 2021). Furthermore, eyewitness testimony is often the primary evidence in investigations and court proceedings related to these crimes, especially when there is limited physical evidence or the accused perpetrator has no known history of violence (Lievore, 2004; Silva, 2022).

In the context of misidentification, as discussed above, sexual crimes are often particularly susceptible, especially when the perpetrator is a stranger to the victim or eyewitnesses (Gross et al., 2005). In fact, a review of exonerations in the USA found that of 121 rape case exonerations, 88% had involved convictions based on eyewitness identifications that had turned out to be mistaken (Gross et al., 2005). This has significant implications, particularly in light of the increased reporting of sexual crimes, which indicate that investigations and court cases related to gendered sexual violence will only increase in coming years. Furthermore, some high-profile cases that emerged from the #MeToo movement, such as Harvey Weinstein, have also highlighted the way that research regarding eyewitness memory accuracy is used – or even misused – within the criminal justice system (Conway, 2021). The prominence of these cases in recent years along with more general issues related to gendered crime could lead to broader misperceptions about gender differences in witness memory. That is, while the above examples highlight the role of witness memory and identification within gendered crime, the question of gender differences in witness memory also applies more generally to non-gendered crime. Gaining a better understanding of how sex and gender may affect eyewitness memory is therefore of ongoing relevance.

It is equally important to note that increased awareness of issues such as incomplete, inaccurate memories and misidentification does not mean that eyewitness memory should be discredited as a useful form of evidence. While the literature has demonstrated that eyewitness memory is malleable, this does not mean it is inherently unreliable, although this perception has gained traction, particularly within the legal system (Wixted et al., 2018). Disregarding eyewitness evidence can come with its own negative consequences as being disbelieved or having their memory doubted can be a source of secondary traumatisation for eyewitnesses, particularly when they are also the victim (Mason & Lodrick, 2013). Furthermore, despite rising awareness of the malleability of eyewitness memory, eyewitness testimony will remain an important form of evidence in both civil and criminal cases, including for crimes such as sexual assault. Given the implications for both the over- and under-estimation of eyewitness memory accuracy, it is therefore important to gain a better understanding of whether sex/gender does influence eyewitness memory, and the conditions under which this may have a particular effect.

Purpose of the scoping review

Scoping reviews are a useful tool for mapping the evidence in a broad area of research in order to determine the extent of the available evidence, how the research has been conducted, and also to clarify gaps in the literature (Peters et al., 2015). Therefore, given the variability in approaches, methodologies, and findings of the literature to date, this type of review is the most suitable for our purposes. To our knowledge, no other scoping review has been conducted on this topic. The objective of this scoping review is to examine and map the range of research that has been conducted on the topic of sex differences in eyewitness memory. The specific questions for review were:

-

1.

Are there sex differences in eyewitness memory and, if so, what are they?

-

2.

If differences have been found, what explanations have been proposed for them?

-

3.

What methodologies have been used to examine sex differences in this context?

Method

A scoping review protocol was developed based on the methods outlined by the Joanna Briggs Institute Methods Manual for scoping reviews, and findings are reported in accordance with the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018).

Eligibility criteria

The following inclusion criteria were defined to guide the search process and decisions on the sources to be included in the review:

-

Published in the English language: for the feasibility and timely completion of the review.

-

Years 1970–2022: this is the period during which most of the relevant eyewitness research has been conducted.

-

Adults aged 18 years and older: children’s eyewitness memory is a separate area with its own research literature and age could be a confounding factor.

-

Primary research: as we are trying to map the research that has been conducted to date and how it has been conducted.

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Review articles (systematic reviews, meta-analyses, etc.)

Databases

Seven databases were selected and searched for this review. These were APA PsycInfo via EBSCO, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, MEDLINE via EBSCO, Web of Science Core Collection, Proquest, Scopus, and HeinOnline. The authors, together with an experienced librarian, judged that these seven databases would be able to reach all the journals and articles relevant to the research question. By using the search terms and databases, a total of 1,424 results were found.

Search strategy

Key terms were selected to be used in constructing search terms for each concept in order to find as many relevant results as possible (Table 1). Search strings were adjusted as appropriate for each database. Results were filtered by date range (1970–2022) where needed, and language (English). Searches in each database were documented and final results were exported to EndNote (X9) where duplicates were removed. The full search for the APA PsycInfo via EBSCO database is documented in Appendix Table 4. Reference lists of the identified papers were examined and citation searching was undertaken to identify any additional articles of relevance that were not found through database searches.

Selection of sources

Studies for review were selected through a three-stage screening process. In the first stage, titles were reviewed to determine the eligibility according to the keywords and the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Abstracts were then screened, with those that were relevant to the research questions and that met the criteria selected for inclusion. Finally, the full text of each article was examined for compliance with the eligibility criteria. There is no specific process for evaluating quality outlined by the scoping review methodology, and as this is not a specific aspect of the research questions outlined for this review, full-text articles were included as long as they met the eligibility criteria and were sufficiently relevant to the research question and objectives. Three articles were excluded in this final stage as they were not able to provide information for answering the review questions for the following reasons: one included only female participants and thus did not provide information regarding sex differences; one focused on personality differences with insufficient information about sex differences; and one was not conducted in the context of eyewitness memory.

Data charting

A data-extraction framework was developed (Table 2) and data were extracted from the articles and summarised into tables. The data-charting tables were updated continually in an iterative process. The information extracted included year of publication, country of origin/publication, population/sample size, methodology, findings related to research question, explanation/theoretical framework for findings. The information extracted was considered to be sufficient for answering the research questions.

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

Of the 918 unique articles found with the search strategy, 22 were selected as eligible for the scoping review. The selection process is documented in Fig. 1.

Characteristics and results of sources of evidence relating to research question

Among the final 22 articles, all were peer-reviewed journal articles excepting one, which was a doctoral dissertation (Bothwell, 1985). The studies were spread over seven different countries, with 11 conducted in the USA (50%). There were three from the United Kingdom (13.6%). There were two each (9.1%) from Australia, Canada, and Slovenia, and one each (4.5%) from Sweden and Bosnia and Herzegovina. The research spanned 42 years in total, with the earliest study published in 1978 and the most recent in 2020. By decade, there were three from the 1970s (13.6%), three from the 1980s (13.6%), seven from the 1990s (31.8%), three in the 2000s (13.6%), four in the 2010s (18.2%), and three from the 2020s so far (13.6%). It is worth noting that 27.3% of these papers were published in the 10 years to 2022, indicating the current interest in this topic.

Of the studies, 17 included a participant sample of university/college students (77.3%), one (4.5%) drew participants from a university community (both staff and students), two from the general public (9.1%), one (4.5%) used existing witness statements from real criminal investigations, and one did not provide population information (4.5%). Nine articles (40.9%) did not provide information about participant age ranges or averages. Due to the high proportion of university/college samples, in those articles that did provide age-related information, the majority of the participant samples had a mean age that was below 27 years old. Regarding the methods used to assess eyewitness memory, 14 studies (63.6%) were recall-based, with free and/or cued recall tasks to assess accuracy (e.g., person, place, event details, etc.). There were five studies that included both recall and face-identification tasks (22.7%). There was one facial recognition study (4.5%), and one involving both facial recognition and face identification tasks (4.5%). There was also one study that used a working memory task (4.5%). Six of the studies (27.3%) also measured confidence in memory recall/face identification. Six studies (27.3%) did not provide a proposed explanation for the sex differences or similarities, and therefore do not contribute to answering research question 2. The information extracted from the articles is documented in Table 3.

Discussion

The present scoping review aimed to review the existing literature in order to investigate whether there are sex differences in eyewitness memory, what these differences may be, how they have been studied, and what explanations have been proposed for any differences found. A total of 22 primary research studies from seven countries and spanning a 42-year period (with six in the 10-year period up to 2022) were found and examined to answer these questions.

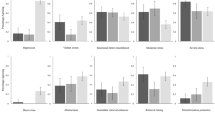

Not all of the studies compared males and females for recall, recognition and/or identification accuracy overall, and findings differed between those that did. However, some trends did emerge. Interestingly, although there was a tendency for males to be significantly more confident in the accuracy of their recall than females, none of the studies found males to be more accurate overall (Areh, 2011; Yarmey & Jones, 1983). On the contrary, three studies found that females had significantly more accurate recall overall and recalled fewer false details (Areh, 2011; Casiere & Ashton, 1996; Zoladz et al., 2014). Lindholm and Christianson (1998), however, found that this female superiority was only evident for cued recall, while the advantage disappeared for free recall. Nonetheless, it was suggested that the higher accuracy demonstrated by females may reflect a more general superiority in episodic memory recall (Lindholm & Christianson, 1998). The remaining studies that measured overall accuracy for recall (Butts et al., 1995; Clifford & Scott, 1978; Loftus et al., 1992; Longstaff & Belz, 2020), face identification (Fazlic et al., 2020), and both recall and face identification (Sharps et al., 2007; Yarmey & Jones, 1983) all found that there were no differences between males and females. It should be noted, however, that Sharps et al. (2007) state that in their study this was due to the fact that there were too few participants in total who made accurate identifications.

Although Butts et al. (1995) suggested that the absence of sex differences overall may indicate that there are no differences to find, the more common consensus was that sex differences may instead lie in the type of information accurately recalled (Areh, 2011; Butts et al., 1995; Powers et al., 1979). Furthermore, studies that compared the quantity of information and number of details recalled consistently demonstrated that there were no differences between males and females (Areh, 2011; Areh & Walsh, 2020; MacLeod & Shepherd, 1986). This suggests that any potential sex differences are not due to differences in the amount of information males and females are each able to recall.

While they may not have found any differences in overall accuracy, many studies did find specific differences in accuracy for specific kinds of information. One fairly consistent finding was that females were significantly more accurate in recalling person-related details, which typically included details about age, height, clothing, hair, and facial features (Areh, 2011; Lindholm & Christianson, 1998; Longstaff & Belz, 2020). This was true even in studies where recall was measured for both a perpetrator and a victim (Areh, 2011; Lindholm & Christianson, 1998). Furthermore, females were also more accurate at identifying the sex of a stranger when this was deliberately kept ambiguous (Longstaff & Belz, 2020). There was also a female advantage for describing and recalling details related to clothing (Horgan et al., 2017; Sharps et al., 2007) and a person’s weight (Yarmey, 1993). However, recall for other general physical features, including eye colour, height, age, and hairstyle, did not differ between males and females (Horgan et al., 2017; Sharps et al., 2007; Yarmey, 1993). Performance for event details has been less consistent, with some studies finding females to be more accurate (Lindholm & Christianson, 1998), and others finding a male advantage (Areh, 2011). Males have also been found to demonstrate greater recall for details related to the surroundings, although once again the difference was small (Longstaff & Belz, 2020).

One study also found that males were more susceptible to the misinformation effect (Loftus et al., 1992), although this was contradicted by a second study, which found that there were no sex differences in resistance to false information (Butts et al., 1995). Overall, the findings seem to indicate that sex differences in eyewitness memory are not a question of whether males or females are more accurate in general, but instead reflect specific differences in the types of information that are recalled more accurately by each.

The most consistent finding to emerge was the own-gender bias effect. Participants were consistently more accurate when recalling details for a person of their own gender and also increased accuracy for recognising and identifying a target person (Areh & Walsh, 2020; Longstaff & Belz, 2020; Palmer et al., 2013; Powers et al., 1979; Shaw & Skolnick, 1994; Shaw & Skolnick, 1999; Wright & Sladden, 2003). Furthermore, participants were also more resistant to suggestion when recalling own-gender details (Powers et al., 1979). While this own-gender bias was common and consistent, some findings suggest that its presence, and the strength of the effect are contingent on other factors. For example, Wright and Sladden (2003) argued that encoding information about a target person’s hair accounts for a significant portion of the own gender bias, proving more useful when making own-sex identification than opposite-sex identification. On the other hand, divided attention during encoding was found to reduce the own-gender bias (Palmer et al., 2013). Furthermore, the presence of specific objects may reverse this effect, with one study finding that accuracy for opposite-sex identification was significantly higher when the person carried a weapon or an unusual object (Shaw & Skolnick, 1999).

Several different suggestions were made to explain why males and females may differ in the types of information they recall. The most common consensus was that these differences result from differences in attentional focus, with males and females attending to different stimuli due to varying levels of interest (MacLeod & Shepherd, 1986; Powers et al., 1979). For instance, one study suggested that the female superiority for accurately recalling person-related details occurs because females have higher level of interest in this type of information and have thus developed more elaborate cognitive categories for it (Lindholm & Christianson, 1998). Similarly, Horgan et al. (2017), suggested that females perform better for recalling clothing and accessories because it is a gendered domain of interest and so more attention is focused to those details.

Perceived threat was another factor that was suggested to direct female attention to person information. Longstaff and Belz (2020) found that females reported higher levels of anxiety and perceived threat, and argued that they may therefore have focused more attention on the stranger out of caution, resulting in better recall for person details. Differences in attentional focus was also the main explanation provided for the own-gender bias effect. One study found that attention during encoding is responsible for a significant portion of this effect (particularly for females), with males and females paying significantly more attention to own-gender faces (Palmer et al., 2013). Some authors suggested a social influence for this bias, arguing that people develop better own-sex recognition because they consume media targeted towards their own gender, which generally contains more own-gender images (Wright & Sladden, 2003). It has also been argued that evolutionary factors direct a person’s attention towards other of their own sex for purposes of social comparison, as there is evolutionary benefit in recognising competition for mating (Horgan et al., 2017; Wright & Sladden, 2003).

While many of the studies suggested possible explanations for the differences found between males and females, the majority of these were based on post-hoc theorising. As such, no measures were included in these studies (with the exception of Longstaff & Belz, 2020) to test the explanations proposed. This presents an issue when attempting to answer the second review question. It also highlights a significant gap in the literature, as there is still a lack of sound, evidence-based theories to explain why sex differences in eyewitness memory may occur. Given that the findings of this review indicate that sex differences do exist for specific types of information, clarifying the reasons for these effects is of importance. Future research in this area should therefore focus on designing methodologies that are able to empirically test theoretical explanations.

Through our review of these articles, it is clear that there is significant variation in the way that the research has been conducted. This is not surprising, given that the topic of eyewitness memory is such a broad one. Most of the studies included in this review measured eyewitness memory by creating mock eyewitness scenarios in videos or a series of images and then measured accuracy for details related to those scenes. However, even for those studies with broadly consistent methodologies, the content of these scenes varied, ranging from violent crimes (robbery, manslaughter, assault/rape) to ambiguous scenes, and even to innocuous scenes such as male and female targets introducing themselves. The methods used to measure memory also differed between articles. For instance, while some studies measured recall accuracy using free recall tasks, others used cued recall questionnaires or checklists, and some used a combination of these methods. Furthermore, it must be noted that while the studies referred to multiple-choice questions and checklists as cued recall tasks, these are technically recognition tasks. The lack of consistency in the methodologies and terminology used between studies reflects the complexity of eyewitness memory as a topic for research, and may help to explain the lack of consensus regarding sex or gender differences across the literature.

The diverse methodologies also make it difficult to definitively conclude whether there are sex differences in eyewitness memory and what the differences may be. Given that the literature on sex differences is limited compared to other topics in eyewitness memory research, this variability in both methodology and terminology presents issues when it comes to comparing and generalising findings between studies. Therefore, further research with more consistent methodologies is needed to develop a reliable foundation within the literature and also to develop a more systematic approach to answering the question, or aspects thereof.

The research reviewed here also spans more than 40 years. Eyewitness memory research, and the field of cognitive psychology more broadly, has developed significantly during this time, and so too has research on sex and gender. This presents potential difficulties with comparing the findings of the earlier studies to those of more recent research. The majority of the studies drew their participant samples from university or college cohorts, which also makes it difficult to generalise the findings to the broader public. Furthermore, the vast majority of the included articles were from developed countries, with half of the research conducted and published in the USA. This lack of cultural diversity provides little opportunity to gain insight into how these findings compare across different countries and cultures. Furthermore, many of the studies reviewed suggested social influences as a factor that may explain how and why males and females may differ in some aspects of eyewitness memory. Therefore, it is relevant to gain a better understanding of how cultural differences in social stereotypes surrounding gender may influence sex differences in eyewitness memory, particularly as many of these western/developed countries become increasingly multicultural.

Our scoping review also had some limitations. While we sought to examine sex differences in eyewitness memory, it must be noted that all the studies reviewed relied on self-reported sex/gender. Furthermore, the terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ were used interchangeably through most of the studies, all of which seem to have assumed both terms to refer to sex and gender as the biological variable (male or female). When extracting data and discussing the studies, we have therefore used the terms as they were used in each article. Furthermore, the language limiter used in the search strategy may mean that some relevant articles were excluded. Nevertheless, the number of search results in languages other than English were very low, indicating that the majority of relevant results were captured by the search strategy.

There are also limitations inherent to the screening processes employed when conducting scoping (and other) reviews. It is possible that there were some studies captured by the initial search strategy that do contain some relevant findings or analyses related to sex or gender differences in eyewitness memory but where this information was not mentioned in the title or abstract. For example, these findings might be incidental to the main focus of the study and only briefly noted in the body text. In these cases, following the PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews, the full text would not be read and this information would be missed. These then end up being excluded during the initial stages of the screening process when examining the titles and abstracts. The screening process is both time and labour-intensive and therefore it is not feasible to examine the full texts for every article captured by the original database searches.

Conclusion

This scoping review is the first such review of the literature related to sex differences in eyewitness memory. Although this topic has maintained sustained research interest and been subject to investigation since at least the 1970s, the literature is limited and lacks consensus. However, despite the variability in methodologies and findings, some interesting trends emerge. Firstly, findings from the studies reviewed here suggest that neither males nor females have a clear advantage for accuracy overall, but that they may instead be more accurate for different types of information. There was a tendency for females to demonstrate significantly higher accuracy for person-related memory, perhaps due to differential interest and attention in that type of information. There was also some evidence that males had a slight advantage for details related to the surrounding environment. The most consistent, though not universal, finding was that both males and females typically perform better in identifying, recognising, and recalling details related to a person of their own gender. This own-gender bias was suggested to be the result of people focusing greater attention on members of their own sex due to social and/or evolutionary factors. Overall, the diversity of findings related to the diversity of methodologies may indicate that any differences between males and females are context and task specific. Although there was some consensus for the proposed attentional component for these sex differences, no compelling causal information or evidence was provided for why differences may occur. Given the ongoing scientific, social, and political relevance of this topic, future research should seek to clarify if and how attentional focus may differ between males and females, and how this translates to differences in eyewitness memory.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Areh, I. (2011). Gender-related differences in eyewitness testimony. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(5), 559–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.11.027

Areh, I., & Walsh, D. (2020). Own-gender bias may affect eyewitness accuracy of perpetrators’ personal descriptions. Revija Za Kriminalistiko in Kriminologijo, 71(4), 247–256.

Bothwell, R. K. (1985). The effects of gender and arousal on facial recognition and recall [Doctoral dissertation, Florida State University]. APA PsycInfo.

Butts, S. J., Mixon, K. D., Mulekar, M. S., & Bringmann, W. G. (1995). Gender differences in eyewitness testimony. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 80(1), 59–63. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1995.80.1.59

Casiere, D. A., & Ashton, N. L. (1996). Eyewitness accuracy and gender. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 83(3), 914. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1996.83.3.914

Clifford, B. R., & Scott, J. (1978). Individual and situational factors in eyewitness testimony. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63(3), 352–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.63.3.352

Conway, A. (2021). The abuse of science to silence the abused. In V. Sinason & A. Conway (Eds.), Trauma and memory: The science and the silenced (pp. 54–67). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003193159-7

Fazlic, A., Deljkic, I., & Bull, R. (2020). Gender effects regarding eyewitness identification performance. Criminal Justice Issues - Journal of Criminal Justice, Criminology and Security Studies, 5, 31–42. https://doi.org/10.51235/kt.2020.20.5.31

Gross, S. R., Jacoby, K., Matheson, D. J., & Montgomery, N. (2005). Exonerations in the united states 1989 through 2003. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 95(2), 523–560.

Horgan, T. G., McGrath, M. P., Bastien, C., & Wegman, P. (2017). Gender and appearance accuracy: Women’s advantage over men is restricted to dress items. The Journal of Social Psychology, 157(6), 680–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2017.1282848

Innocence Project. (2020). How eyewitness misidentification can send innocent people to prison. Retrieved April 10, 2022, from https://innocenceproject.org/how-eyewitness-misidentification-can-send-innocent-people-to-prison/

Levy, R., & Mattsson, M. (2020). The effects of social movements: Evidence from #MeToo. Social Science Research Network, 1–67. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3496903

Lievore, D. (2004). Victim credibility in adult sexual assault cases. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice (288), 1–6. https://www.aic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/tandi288.pdf

Lindholm, T., & Christianson, S. -Å. (1998). Gender effects in eyewitness accounts of a violent crime. Psychology, Crime & Law, 4(4), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683169808401763

Loftus, E. F., Levidow, B., & Duensing, S. (1992). Who remembers best: Individual-differences in memory for events that occurred in a science museum. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 6(2), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2350060202

Longstaff, M. G., & Belz, G. K. (2020). Sex differences in eyewitness memory: Females are more accurate than males for details related to people and less accurate for details surrounding them, and feel more anxious and threatened in a neutral but potentially threatening context. Personality and Individual Differences, 164, 110093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110093

Macleod, M. D., & Shepherd, J. W. (1986). Sex differences in eyewitness reports of criminal assaults. Medicine, Science and the Law, 26(4), 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/002580248602600413

Mason, F., & Lodrick, Z. (2013). Psychological consequences of sexual assault. Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 27(1), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.08.015

Palmer, M. A., Brewer, N., & Horry, R. (2013). Understanding gender bias in face recognition: Effects of divided attention at encoding. Acta Psychologica, 142(3), 362–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2013.01.009

Pickel, K. L. (2009). The weapon focus effect on memory for female versus male perpetrators. Memory, 17(6), 664–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210903029412

Powers, P. A., Andriks, J. L., & Loftus, E. F. (1979). Eyewitness accounts of females and males. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64(3), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.64.3.339

Sharps, M. J., Hess, A. B., Casner, H., Ranes, B., & Jones, J. (2007). Eyewitness memory in context: Toward a systematic understanding of eyewitness evidence. Forensic Examiner, 16(3), 20–27.

Shaw, J. I., & Skolnick, P. (1994). Sex differences, weapon focus, and eyewitness reliability. Journal of Social Psychology, 134(4), 413–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1994.9712191

Shaw, J. I., & Skolnick, P. (1999). Weapon focus and gender differences in eyewitness accuracy: Arousal versus salience. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(11), 2328–2341. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00113.x

Silva, T. C. (2022). Assessment of credibility of testimony in alleged intimate partner violence: A case report. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 22(1), 58–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2021.1945836

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., McInerney, P., Baldini Soares, C., Khalil, H., & Parker, D. (2015). The Joanna Briggs institute reviewers’ manual 2015: Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Tidmarsh, P., & Hamilton, G. (2020). Misconceptions of sexual crimes against adult victims: Barriers to justice. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice (611). https://doi.org/10.52922/ti04824

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M., Garritty, C … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Wilcox, T., Greenwood, M., Pullen, A., Kelly, A. O., & Jones, D. (2021). Interfaces of domestic violence and organization: Gendered violence and inequality. Gender, Work, and Organisation, 28(2), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12515

Wixted, J. T., Mickes, L., & Fisher, R. P. (2018). Rethinking the reliability of eyewitness memory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(3), 324–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617734878

Wright, D. B., & Sladden, B. (2003). An own gender bias and the importance of hair in face recognition. Acta Psychologica, 114(1), 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-6918(03)00052-0

Yarmey, A. D. (1993). Adult age and gender differences in eyewitness recall in field settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23(23), 1921–1932. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1993.tb01073.x

Yarmey, A. D., & Jones, H. P. (1983). Accuracy of memory of male and female eyewitnesses to a criminal assault and rape. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 21(2), 89–92. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03329962

Zoladz, P. R., Peters, D. M., Kalchik, A. E., Hoffman, M. M., Aufdenkampe, R. L., Woelke, S. A., Wolters, N. E., & Talbot, J. N. (2014). Brief, pre-learning stress reduces false memory production and enhances true memory selectively in females. Physiology & Behavior, 128, 270–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.02.028

Author note

Mitchell G. Longstaff was first author of one of the articles included as part of this review. The other authors declare no conflict of interest. The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the papers as follows: Conceptualisation and design: Emma M. Russell and Mitchell G. Longstaff; Literature search, data analysis and interpretation of results: Emma M. Russell; Writing – original draft preparation: Emma M. Russell; Writing – review and editing: Emma M. Russell, Mitchell G. Longstaff and Heather Winskel.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

Mitchell G. Longstaff was first author of one of the articles included as part of this review. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Open practices statement

The data and materials for this review are available and included within the manuscript. Preregistration of experiments is not applicable to this review.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Russell, E.M., Longstaff, M.G. & Winskel, H. Sex differences in eyewitness memory: A scoping review. Psychon Bull Rev 31, 985–999 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-023-02407-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-023-02407-x