Abstract

We investigated the cognitive processes that cause confidence to increase. Participants were asked 48 general-knowledge questions either once or three times, without feedback. After 2 min (Experiment 1) or 48 h (Experiment 2) they were asked the same questions again, and rated their confidence. Repeated questioning increased confidence but not accuracy. This increase, which replicated research on episodic memory in the eyewitness literature (e.g., Shaw, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied 2: 126–146, 1996), occurred even though accuracy was only around 25%. A mediation analysis identified response repetition, but not fluency, as a mechanism underlying growth in confidence. Thus, the basis for confidence judgments appears to be whether one's current response has been generated previously. In sum, answering a factual question increases confidence, but not accuracy, and this happens because learners use response repetition as a cue for confidence judgments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fluency, or the subjective ease or difficulty of information processing, impacts a wide variety of judgments (Alter & Oppenheimer, 2009). For example, an interviewer who becomes frustrated during an online job interview because of an unstable internet connection and bad audio-visual quality might mistakenly blame the candidate for their negative experience (Fiechter, Fealing, Gerrard, & Kornell, 2018). The present experiments address the misleading role of fluency in judgments about the accuracy of one’s memory (i.e., metacognitive monitoring; Nelson & Narens, 1990); specifically, we assessed how trial-completion times influenced confidence.Footnote 1 Participants report higher confidence in multiple-choice responses that they select more quickly (Koriat, 2008; Koriat & Ackerman, 2010; Robinson, Johnson, & Herndon, 1997; Zakay & Tuvia, 1998), even when accuracy of responses is controlled for (Ackerman & Zalmanov, 2012). Furthermore, primed answers are retrieved more quickly and receive higher confidence ratings than do unprimed answers, regardless of the accuracy of those answers (Kelley & Lindsay, 1993).

Repeated questioning and confidence

In the present experiments, we examined what happens to confidence when a question is asked multiple times. This manipulation has been implemented most frequently in the eyewitness literature as an analogue to repeated police questioning of witnesses for their memory of a crime (Pezdek, Sperry, & Owens, 2007; Shaw, 1996; Shaw & McClure, 1996; Odinot & Wolters, 2006; Odinot, Wolters, & Lavender, 2008; see also Wells, Ferguson, & Lindsay, 1981). These studies have mostly found that eyewitness confidence increases when participants are asked the same question repeatedly. The strongest evidence comes from studies that used multiple-choice questions (Shaw, 1996; Shaw & McClure, 1996); only one study has found confidence inflation with free-response questions (Odinot et al., 2008).

Response fluency has been used to explain why learners' confidence is increased following repeated questioning. The idea is that repeated questioning today enhances retrieval fluency tomorrow, which in turn is used as a cue when learners make confidence judgments (Bjork, Dunlosky, & Kornell, 2013; Koriat, 2012; Odinot et al., 2008; Shaw, 1996; Shaw & McClure, 1996). We will call this account the fluency hypothesis. The fluency hypothesis is based on evidence from the aforementioned answer-priming paradigm used by Kelley and Lindsay (1993); however, there is at least one other plausible mechanism that could explain increases in confidence after repeated questioning: when asked to answer a previously answered question, learners may remember having given the same response earlier (Finn & Metcalfe, 2007, 2008) and use that consistencyFootnote 2 as a cue for their confidence judgment. This consistency would probably be a more salient cue after repeated questioning because of enhanced memory following multiple retrievals (e.g., Karpicke & Roediger, 2008). We will call this account the response-repetition hypothesis. The fluency hypothesis and response-repetition hypothesis both predict increased confidence after repeated questioning, but they are premised on different mediating mechanisms.

Participants in our experiments answered general knowledge questions either once or three times. They then took a final test in which they responded to all the questions for a final time and were asked to assess confidence in their responses. Because participants were never told the correct answers to the questions we asked, we predicted that repeated questioning would not affect response accuracy. We predicted that it would increase confidence, however. Finally, we conducted a proper mediation analysis in order to evaluate whether the fluency hypothesis or response-repetition hypothesis better accounted for our data.

These experiments are important for practical and theoretical reasons. First, on a practical level, there are many situations in which people answer questions and do not look up the answer, and in doing so might increase their confidence in an incorrect answer. One is when one recalls a false autobiographical story that cannot be looked up (e.g., “I once saw Bill Clinton working at a diner in Wichita”). Another is when one does not bother to check a false “fact” because one does not doubt its veracity (e.g., “the Great Wall of China is visible from the moon”). In these cases, an idea could turn from uncertain (“maybe George H. W. Bush masterminded the assassination of JFK?”) to certain (“George H. W. Bush masterminded the assassination of JFK!”) without external confirmation, based solely on thinking about it from time to time and consistently thinking of the same answer.

Second, in terms of theory, we sought to establish the mechanism that underlies this phenomenon: How and why does repeated questioning cause changes in confidence? This question fits with a recent push to understand the mechanisms underlying metacognitive judgments, including confidence judgments (Koriat & Adiv, 2016). As previously stated, researchers have postulated that repeated questioning increases confidence via fluency; this research sought to test predictions made by the fluency and response-repetition hypotheses.

Experiment 1

Method

Our experimental method and statistical analyses are preregistered at the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/w4kp6. We analyzed our data using Bayesian analyses, which allow for the use of optional stopping during data collection (Rouder, 2014; for mathematical proof, see Deng, Lu, & Chen, 2016). We therefore collected data from 60 people and analyzed our data, with a commitment to collect data from 40 additional people if the data were inconclusive, but to stop if we found convincing evidence in favor of or against our hypotheses. Bayes Factors for all comparisons of interest (test accuracy, confidence, trial-completion time, and coefficients from a mediation analysis) were assessed as part of this optional stopping.

Participants

We recruited 100 participants from Amazon's Mechanical Turk Service. Participants were paid $3.00 to complete the experiment, which lasted approximately 25 min. We then excluded participants who: (1) did not complete every phase of the experiment; (2) started the experiment multiple times; (3) failed to report being fluent in English; (4) reported technical difficulties; (5) reported seeing our stimuli before; or (6) had a median trial completion time of less than 2 s over all phases of the experiment (these exclusion rules were preregistered). Of the subjects who completed all parts of the experiment, five were removed for having a median trial time of less than 2 s and seven were removed for starting the experiment multiple times. We excluded one additional participant because they did not make any commission errors on the repeated questions and so their data could not be analyzed. The final sample consisted of 84 participants.

Design

We used a two-level (number of times asked: once vs. three times) within-subject design. Our dependent variables were accuracy, trial-completion time, and confidence on the final test.

Stimuli

We used 48 general knowledge questions taken from Kornell (2014). Example questions include "What nation consumes the most Coca-Cola per person?" (Iceland) and "What is a group of owls called?" (parliament).

Procedure

The experiment consisted of an initial practice phase followed by a brief distractor and then a final test phase. All trials were self-paced. Participants responded to 48 general knowledge questions during the practice phase; we instructed them to guess even if they were uncertain about their responses. These questions were presented one at a time and participants typed their responses into an empty box placed below each question; they submitted their responses by pressing the "Enter" key on their keyboard. We measured trial-completion time as the temporal span between the onset of a question and the submission of a response. At no point in the experiment were participants shown the correct responses to these questions. Half the questions were asked once and the other half three times. We structured the practice phase so that it consisted of three blocks; each block consisted of all 24 repeated questions and eight single questions (i.e., one-third of the single questions was randomly assigned to each of the three practice blocks). The question order in each block was randomly determined.

After completing the practice phase, participants completed a brief distractor in which they were asked to recall as many sports as they could think of for 2 min. Then, on the final test, they were asked all 48 questions once more. On each trial, after providing a response, they were asked "How confident are you in your response?" and typed an integer from 1 to 7 into an empty box placed below the prompt, pressing the "Enter" key to submit their rating. Participants' answers to the questions were initially leniently scored by the PHP "similar_text" function and were counted as correct if that function returned a value of 75 (out of 100) or higher. Responses that were scored as incorrect were hand-scored for accuracy; only 65 responses across both experiments (out of 18,615) were scored as correct after initially being classified as incorrect. A summary of these responses is presented in Table S1 of the Online Supplementary Materials (OSM).

Results

All our data and an R script for running our analyses are located at the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/w4kp6/.

We analyzed our data using Bayesian t-tests (Rouder, Speckman, Sun, Morey, & Iverson, 2009). We report Bayes Factors (BF10), which are a ratio of evidence in favor of the alternative and null hypotheses. Following recommendations from Jeffreys (1961), we consider evidence convincing if BF10 ≤ 0.33 (for the null) or BF10 ≥ 3 (for the alternative).

We removed questions from each participant's data file for which there was at least one omission error. This policy was not included in our preregistration file, but we were interested in the effects of repeated answering on confidence and omission errors, which do not involve answering at all, were irrelevant to that relationship. We ultimately removed 1,030 trials (i.e., 9% of the original data set).

Accuracy, confidence, and response times

All dependent measures of interest as a function of question repetition are presented in Table 1. We found that confidence in response accuracy was higher for repeated versus single questions, BF10 = 8.10, Cohen's d = 0.47.Footnote 3 This difference in confidence was not mirrored by actual performance: accuracy on the final test for repeated versus single questions was approximately the same, BF10 = 0.25. Median trial-completion time on the final test was faster for repeated questions than for single questions, BF10 = 6,151.84, d = 0.91.

Mediation analysis

Finally, we conducted a Bayesian mixed-effects mediation analysis (Kenny, Korchmaros, & Bolger, 2003) with group-level effects for each item and question. Details of the analysis are included in the OSM. We initially pre-registered an analysis that included trial-completion time as a lone mediator (this analysis is presented in the OSM). However, further examination of our data showed that learners were more likely to repeatFootnote 4 answers from the practice phase in the repeated-questioning condition (see Table 1), and so we hypothesized that this enhanced response repetition may also be mediating that relationship. We therefore conducted a mediation analysis with two mediators (see, e.g., Preacher & Hayes, 2008): trial-completion time and response repetition (i.e., whether a final-test response had been provided previously during the practice phase or not).

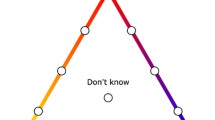

The parameter estimates from the two-mediator analysis are presented in Fig. 1. Bayes Factors for our mediation analyses were calculated via Savage-Dickey ratios (Wagenmakers, Lodewyckx, Kuriyal, & Grasman, 2010). In contrast to the fluency hypothesis, we found strong evidence that trial-completion time did not mediate the relationship between repeated questioning and confidence (i.e., a1b1 + σab; BF10 = 0.003); in support of the response-repetition hypothesis, we found evidence that response repetition did mediate this relationship (i.e., a2b2 + σab; BF10 = 13.11).Footnote 5 Furthermore, evidence for a direct relationship between confidence and repeated questioning supported the null (i.e., c'; BF10 = 0.16), suggesting that response repetition completely mediated that relationship. It thus appears that participants were more likely to give a repeated response at test if they were asked a question three times during practice and that they were more confident in these repeated responses.

Posterior means (standard deviations in parentheses) from our mixed-effects mediation analysis using response times and probability of a repeated response as mediators in Experiment 1. Values in bold font indicate a corresponding Bayes Factor that is ≥ 3. Values of a correspond to the relationship between our independent variable (i.e., "# Asked") and a mediating variable after controlling for the other mediating variable; values of b correspond to the relationship between a mediating variable and our outcome variable of interest (i.e., "Confidence") after controlling for the independent variable and other mediating variables. The product of a and b, plus their covariance at the group level (i.e., ab + σab), corresponds to the mediating effect of a variable (Kenny et al., 2003). Values of c' correspond to the relationship between our independent variable and the outcome variable of interest after controlling for both mediating variables

Discussion

Experiment 1 suggested that repeated questioning increases confidence in responses to general knowledge questions, replicating and extending previous studies in the eyewitness literature (e.g., Shaw, 1996). Most notably, our mediation analysis suggested that trial-completion time did not mediate the relationship between repeated questioning and enhanced confidence, but that response repetition did. Experiment 1 provided clear support for the response-repetition hypothesis over the fluency hypothesis.

Experiment 2

One possible reason why trial-completion time did not mediate the repeated questioning-confidence relationship in Experiment 1 is because we had participants report their confidence after a very brief 2-min delay. Previous findings suggest that reliance on processing fluency increases following a delay. For example, the oft-cited false-fame effect (Jacoby, Woloshyn, & Kelley, 1989b) occurs after a 24-h delay, but not immediately (Jacoby, Kelley, Brown, & Jasechko, 1989a). It seemed possible that delay would have similar effects in our study. Thus, in Experiment 2 we extended the delay between initial exposure to the questions and the final test to 48 h. Doing so had the added advantage of increasing the realism of the study, given that longer delays are more representative of how repeated questioning might happen in everyday life.

Method

Our experimental method and statistical analyses are preregistered at the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/w4kp6.

Participants

Unlike Experiment 1, we did not use optional stopping for data collection in Experiment 2. Instead, we initially collected data from 100 people from Amazon's Mechanical Turk Service and then analyzed data from participants who returned 48 h later to complete the second session. Participants were paid $2.00 for completing the first session and $1.00 for completing the second session. We ended up with 55 participants after excluding those subjects who met any of our exclusion criteria or did not complete the second session. Our exclusion rules were the same as in Experiment 1; of the subjects who completed all parts of the experiment, one was removed for having a median trial time of less than 2 s, one was removed for starting the experiment multiple times, and one was removed for reporting technical difficulties.

Design, Stimuli, and Procedure

Our design, stimuli, and procedure were identical to Experiment 1, with two exceptions. First, we now included a 48-h delay between the initial practice of questions and the final test. Second, during the final test, we asked participants to report whether the current question had been asked once or three times during their first session.Footnote 6

Results

As was the case for Experiment 1, we removed items that had not been responded to at any point during the experiment. We ultimately removed 368 observations (i.e., 5% of the original data set).

Accuracy, confidence, and response times

The pattern of condition means replicated Experiment 1, as can be seen in Table 1. We found that confidence in response accuracy was higher for repeated versus single questions, BF10 = 6.88, d = 0.57. This difference in confidence was not mirrored by actual performance: Accuracy on the final test for repeated versus single questions was approximately the same, BF10 = 0.16. Median trial-completion time (on the final test) for repeated questions was faster than for single questions, BF10 = 6.41 × 108, d = 2.36.

Mediation analysis

We preregistered an analysis with trial-completion time as a sole mediator (presented in the OSM) but present here a two-mediator analysis with time and response repetition as mediators. The parameter estimates from this analysis are presented in Fig. 2. In contrast to the fluency hypothesis, we found evidence for no mediating role of trial-completion time (i.e., a1b1 + σab; BF10 = 0.09); in support of the response-repetition hypothesis, we found very strong evidence for a mediating role of response repetition (i.e., a2b2 + σab; BF10 = 6.69 × 1020). Furthermore, we found strong evidence for no direct contribution of repeated questioning (i.e., c'; BF10 = 0.06), suggesting that response repetition once again accounted for much of that variable's effect.

Posterior means (standard deviations in parentheses) from our mixed-effects mediation analysis using response times and probability of a repeated response as mediators in Experiment 2. Values in bold font indicate a corresponding Bayes Factor that is ≥ 3. See Fig. 1 for an interpretation of the parameters

Discussion

In Experiment 2 we had participants wait 48 h between initially responding to trivia questions and then making their final responses and confidence judgments. We replicated the finding from Experiment 1 that repeated questioning increased response speed and confidence without affecting response accuracy. And, once again, increased speed did not mediate the repeated questioning-confidence relationship. Rather, response repetition mediated that relationship. Experiment 2 therefore replicated the support for the response-repetition hypothesis over the fluency hypothesis that we found in Experiment 1.

General discussion

Participants in both experiments gave higher confidence ratings on the final test when questions had been asked multiple times during an earlier practice phase than when they had been asked once. There was no concomitant increase in response accuracy, which suggests that increased confidence was not justified. These experiments replicated and extended similar effects found in the eyewitness literature (Shaw, 1996; Shaw & McClure, 1996; Odinot, Wolters, & Lavender, 2008) to semantic, factual knowledge of the kind that people habitually generate in daily life.

Critically, and unlike previous studies, these experiments examined the causal relationship that links repeated questioning to increased confidence. Mediation analysesFootnote 7 suggested that response repetition, and not trial-completion time, mediated the repeated questioning-confidence relationship. This result held when participants gave their final answers 2 min (in Experiment 1) and 2 days (in Experiment 2) after practicing the questions. These findings support the response-repetition hypothesis and not the fluency hypothesis. Finally, it is important to note that we did find a mediating role of trial-completion time in a single-mediator analysis for Experiment 2, which suggests that our study was in fact capable of detecting a mediating role of fluency in the two-mediator analysis had such a role been present.

Our findings provide clear counter-evidence to the fluency hypothesis (and, more generally, to any account that predicts a mediating role of response time; Koriat, 2012), which has received virtually uncontested support as an explanation for confidence in repeated questions in the metacognitive literature. It appears to be the case that learners monitor the consistency between a current response and past responses and use that repetition as a cue for confidence. That repeated responses happen to be given more quickly is probably why previous studies (e.g., Shaw, 1996) mis-identified fluency as a mediating variable.

Our data are consistent with past studies that have found retrieval success to be a basis for metacognitive judgments (Dunlosky & Nelson, 1992; Finn & Metcalfe, 2007, 2008; Nelson & Dunlosky, 1991; Spellman & Bjork, 1992). However, in previous studies, participants had learned the answers during the study, so recalling the same answer as before (typically) meant recalling the correct answer. This study was different, in that our participants had generated their answers in the absence of feedback, so they had no confirmation that their initial answers were correct. It is interesting that confidence increased when accuracy held steady at only around 25%. Our participants had very little reason to suspect that they were generating correct information during the practice phase, but even so, recalling the same answer again during the test phase seemed to make them more confident.

It is circular reasoning to decide your opinion today must be correct because, in the past, you had the same opinion. Yet this scenario appears to be what happened to our participants. They were not more correct after answering questions more times, but they thought they were. This effect of repeating oneself on confidence could help explain why people are generally overconfident in their knowledge.

Notes

Trial-completion time could be diagnostic of several kinds of fluency, including retrieval fluency, reading fluency, conceptual fluency, etc. Because fluency in general consistently produces more positive judgments (Alter & Oppenheimer, 2009), we were interested in whether learners use trial-completion time as a cue, regardless of what specific type(s) of fluency that time is indexing. In this article, we use the terms fluency and trial-completion time interchangeably.

Note that we use the term "consistency" in the retrospective sense of comparing a current response to previous ones. Specifically, our use is different from that of Koriat (Koriat, 2012; see also Koriat & Adiv, 2016), whose self-consistency model of confidence posits that confidence ratings reflect prospective consistency (i.e., the likelihood that a current response will be produced again on a future trial). The self-consistency model is not directly relevant to our experiments because the kind of consistency we focused on was whether the current response was consistent with a response one made in the past, not a response to be made in the future.

The difference in average confidence was rather small in each of our experiments. However, this difference could be made larger by increasing the disparity in item repetition between our experimental conditions.

We deemed an answer to be a repetition if it was provided at any point during the practice phase and also on the final test. That is, for questions asked three times, an answer did not have to be given on all three practice trials to be considered a repetition.

To ensure that our participants were not merely repeating items for which they already had high confidence (Koriat, 2012; Saito, 1998), we conducted a control analysis in which we switched the positions of repeated response and confidence in our two-mediator model (this analysis is reported in the OSM). We found no evidence for this reverse causality in either of our experiments. (We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this analysis.)

This additional question was intended to serve as an assessment of source memory; we intended to analyze separately those items for which participants made a source-memory error. However, in retrospect we realized that we asked the wrong question because we were interested in participants' memory for their initial exposure to each item, which was not necessarily assessed by asking about number of repetitions. Therefore, we do not report analyses of this question in the main article. The analyses are instead reported in the OSM.

Causal inferences should be interpreted cautiously with mediation analyses, because mediating variables identified as part of these analyses could be correlates of an unidentified, true mediator (Fiedler, Schott, & Meiser, 2011). Even so, our selection of potential mediators was consistent with claims made in previous studies (Finn & Metcalfe, 2007, 2008; Shaw, 1996).

References

Ackerman, R., & Zalmanov, H. (2012). The persistence of the fluency-confidence association in problem solving. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19, 1187–1192.

Alter, A. L., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2009). Uniting the tribes of fluency to form a metacognitive nation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13, 219–235.

Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, Techniques, and Illusions, Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 417–444.

Deng, A., Lu, J., & Chen, S. (2016). Continuous monitoring of A/B tests without pain: Optional stopping in Bayesian testing. In Proceedings of 2016 IEEE international conference on data science and advanced analytics (DSAA). https://doi.org/10.1109/DSAA.2016.33

Dunlosky, J., & Nelson, T. O. (1992). Importance of the kind of cue for judgments of learning (JOL) and the delayed-JOL effect. Memory & Cognition, 20, 374–380.

Fiechter, J. L., Fealing, C., Gerrard, R., & Kornell, N. (2018). Audiovisual quality impacts assessments of job candidates in video interviews: Evidence for an AV quality bias. Cognitive Research. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-018-0139-y

Fiedler, K., Schott, M., & Meiser, T. (2011). What mediation analysis can (not) do. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1231–1236.

Finn, B. & Metcalfe, J. (2007). The role of memory for past test in the underconfidence with practice effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 33, 238–244.

Finn, B. & Metcalfe, J. (2008). Judgments of learning are influenced by memory for past test. Journal of Memory and Language, 58, 19–34.

Jacoby, L. L., Kelley, C., Brown, J., & Jasechko, J. (1989a). Becoming famous overnight: Limits on the ability to avoid unconscious influences of the past. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 326–338.

Jacoby, L. L., Woloshyn, V., & Kelley, C. (1989b). Becoming famous without being recognized: Unconscious influences of memory produced by dividing attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 118, 115–125.

Jeffreys, H. (1961). Theory of probability (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press, Clarendon Press.

Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science, 319, 966-968.

Kelley, C. M., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Remembering mistaken for knowing: Ease of retrieval as a basis for confidence in answers to general knowledge questions. Journal of Memory and Language, 32, 1–24.

Kenny, D. A., Korchmaros, J. D., & Bolger, N. (2003). Lower level mediation in multilevel models. Psychological Methods, 8, 115–128.

Koriat, A. (2008). Subjective confidence in one's answers: the consensuality principle. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 34, 945–959.

Koriat, A., & Ackerman, R. (2010). Choice latency as a cue for children’s subjective confidence in the correctness of their answers. Developmental Science, 13, 441-453.

Koriat, A. (2012). The self-consistency model of subjective confidence. Psychological Review, 119, 80–113.

Koriat, A., & Adiv, S. (2016). The self-consistency theory of subjective confidence. In J. Dunlosky & S. K. Tauber (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of metamemory (p. 127 – 147). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kornell, N. (2014). Attempting to answer a meaningful question enhances subsequent learning even when feedback is delayed. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40, 106–114.

Nelson, T. O., & Dunlosky, J. (1991).When people's judgments of learning (JOLs) are extremely accurate at predicting subsequent recall: The "delayed-JOL effect". Psychological Science, 2, 267–270.

Nelson, T. O., & Narens, L. (1990). Metamemory: A theoretical framework and new findings. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (pp. 125-141). New York: Academic Press.

Odinot, G., & Wolters, G. (2006). Repeated recall, retention interval and the accuracy–confidence relation in eyewitness memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 973-985.

Odinot, G., Wolters, G., & Lavender, T. (2008). Repeated partial eyewitness questioning causes confidence inflation but not retrieval-induced forgetting. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23, 90–97.

Pezdek, K., Sperry, K., & Owens, S. M. (2007). Interviewing witnesses: The effect of forced confabulation on event memory. Law and Human Behavior, 31, 463–478.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Robinson, M. D., Johnson, J. T., & Herndon, F. (1997). Reaction time and assessments of cognitive effort as predictors of eyewitness memory accuracy and confidence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 416–425.

Rouder, J. N. (2014). Optional stopping: No problem for Bayesians. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21, 301–308.

Rouder, J. N., Speckman, P. L., Sun, D., Morey, D. M., & Iverson, G. (2009). Bayesian t tests for accepting and rejecting the null hypothesis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 225–237.

Saito, M. (1998). Fluctuations of answer and confidence rating in a general-knowledge problem task: Is confidence rating a result of direct memory-relevant output monitoring? Japanese Psychological Research, 40, 92–103.

Shaw, J. S., III (1996). Increases in eyewitness confidence resulting from postevent questioning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 2, 126–146.

Shaw, J. S., III, & McClure, K. A. (1996). Repeated postevent questioning can lead to elevated levels of eyewitness confidence. Law and Human Behavior, 20, 629–653.

Spellman, B. A., & Bjork, R. A. (1992). When predictions create reality: Judgments of learning may alter what they are intended to assess. Psychological Science, 3, 315–317.

Wagenmakers, E.-J., Lodewyckx, T., Kuriyal, H., & Grasman, R. (2010). Bayesian hypothesis testing for psychologists: A tutorial on the Savage-Dickey method. Cognitive Psychology, 60, 158–189.

Wells, G. L., Ferguson, T. J., & Lindsay, R. C. L. (1981). The tractability of eyewitness confidence and its implications for triers of fact. Journal of Applied Psychology, 66, 688–696.

Zakay, D., & Tuvia, R. (1998). Choice latency times as determinants of post-decisional confidence. Acta Psychologica, 98, 103–115.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Open Practices Statement

The data for all experiments, and an accompanying R script, are available at the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/w4kp6/. Both experiments were preregistered.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 132 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fiechter, J.L., Kornell, N. Answering a factual question today increases one’s confidence in the same answer tomorrow – independent of fluency. Psychon Bull Rev 28, 962–968 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-021-01882-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-021-01882-4