Abstract

Recent evidence from studies using the gaze-contingent boundary paradigm has suggested that parafoveal preview benefit is contingent on the fit between a preview word and the sentence context. We investigated whether this plausibility preview benefit is modulated by preview–target orthographic relatedness. Participants’ eye movements were recorded as they read sentences in which the parafoveal preview of a target word was manipulated. The nonidentical previews were plausible or implausible continuations of the sentence and were either orthographic neighbors of the target or unrelated to the target. All first-pass reading measures showed strong plausibility preview benefits. There was also a benefit from preview–target orthographic relatedness across the reading measures. These two preview effects did not interact for any fixation measure. We also found no evidence that the relatedness effect was caused by misperception of an orthographically similar preview as the target word. These data highlight the existence of two independent mechanisms underlying preview effects: a benefit from the contextual fit of the preview word in the sentence, and a benefit from the sublexical overlap between the preview and target words.

Similar content being viewed by others

Parafoveal processing underpins fluent reading. Studies utilizing the gaze-contingent boundary paradigm (Rayner, 1975) have shown that reading is facilitated when a valid preview of the upcoming word is available in the parafovea. Although it is well established that this preview benefit also extends to items that share orthographic and/or phonological features with the target word (see Schotter, Angele, & Rayner, 2012), more recent studies have suggested that parafoveal words are sometimes processed to the semantic level (Hohenstein & Kliegl, 2014; Schotter, 2013; Schotter, Lee, Reiderman, & Rayner, 2015; Veldre & Andrews, 2016b). This evidence has raised questions about the precise mechanisms underlying preview effects.

Semantic preview effects are theoretically significant because they implicate deep parafoveal processing that was, until recently, thought not to occur in English (e.g., Rayner, Schotter, & Drieghe, 2014). To provide insight into semantic parafoveal processing, Veldre and Andrews (2016a) investigated whether semantic preview benefit is caused by facilitation from overlapping semantic features shared by the preview and the target word or from the contextual plausibility of the preview word, two factors that have previously been confounded. The results showed that, when the plausibility of the preview word in the sentence was controlled, no effect of preview–target semantic relatedness on fixation durations emerged. However, preview plausibility had a strong facilitative effect on first-pass reading measures of the target word (see also Schotter & Jia, 2016; Yang, Li, Wang, Slattery, & Rayner, 2014). These data demonstrate that preview benefit depends, in part, on the compatibility of the preview with the context.

These results imply that plausible parafoveal words are at least partially incorporated into the reader’s developing representation of the sentence meaning, perhaps in place of the target word. Such evidence has been interpreted as challenging the standard view that preview effects are due to the integration of preview information with the target word (Schotter & Jia, 2016). However, the absence of preview–target integration may be specific to semantic relationships. Because the preview–target word pairs used to assess semantic preview benefit are selected to have minimal orthographic overlap, interference caused by the orthographic discrepancy between a preview and a target may counteract any benefit of shared semantic features. Nevertheless, it is possible that abstract letter identities are integrated across saccades, even if this is not the case for semantic information. Effects of orthographic preview–target relatedness might therefore co-occur with effects of preview–context compatibility. In the present study, we investigated this by extending Veldre and Andrews’s (2016a) approach of factorially manipulating the preview’s plausibility and relatedness to orthographic preview benefits.

If plausibility preview benefit and orthographic preview benefit are due to separate processes, reflecting contextual facilitation from the match between a preview and the sentence, and integration of letter information between the preview and target, respectively, the two benefits should produce additive effects on fixation duration (Sternberg, 1969). Alternatively, preview plausibility and relatedness might yield interactive effects on fixation duration, suggesting that the two factors affect the same stage of processing.

An interaction between plausibility and relatedness could also arise if orthographically related previews are more likely to be “misperceived” as the target word (e.g., Slattery, 2009). That is, rather than activation of the lexical entry of the preview word, a preview benefit might occur because the target word is occasionally directly activated by the preview. The reduced fixation durations on these trials would then be functionally due to an identical preview benefit. Critically, if the benefit of an orthographic preview relies on misperception, it should be unaffected by the plausibility of the actual preview word, because the preview is misread as the target, which is always a plausible continuation of the sentence. This account therefore predicts a reduced plausibility effect for orthographically similar previews. The present study was designed to directly assess whether preview effects are due to word misperception.

We conducted two subexperiments that used the boundary paradigm to assess the same five preview conditions: an identical preview, and four conditions that factorially manipulated the contextual plausibility of the preview in the sentence and whether or not the preview was a one-letter-different neighbor of the target.

To assess the contribution of misperception of preview words, the target and preview stimuli were based on sets of matched “animal” and “nonanimal” words. Experiment 1A included a comprehension probe after each experimental sentence that asked whether or not the sentence contained an animal. Evidence that target detection was more accurate when the preview was an orthographic neighbor of the target rather than an unrelated word would imply that readers occasionally misperceive a neighbor word preview as the target word. The sentences were constructed to be equally plausible for both animal and nonanimal words at the location of the target word. In approximately one third of the sentences, the target word was an animal. In a further third of the sentences, whereas the target was a nonanimal word, the plausible neighbor preview was an animal word. In the remaining sentences, the target was a nonanimal, but the plausible unrelated preview was an animal word (see Fig. 1).

Examples of the preview conditions used in the experiment: (a) identical, (b) plausible neighbor, (c) implausible neighbor, (d) plausible unrelated, and (e) implausible unrelated. The invisible boundary is represented by the dashed lines. In all conditions, the identical target word was displayed when the reader’s eye crossed the boundary. The three example items show the animal word probe manipulation: (1) animal word as target, (2) animal word as plausible neighbor preview, and (3) animal word as plausible unrelated preview

This manipulation also allowed us to probe whether participants encoded the preview or the target word into their sentence representation. Schotter and Jia (2016) found that participants were more likely to incorrectly report having read the preview word when it was a plausible continuation of the sentence, but only when the target was never directly fixated (i.e., skipped and never subsequently refixated). False detection rates for plausible animal previews for nonanimal targets, or vice versa, would provide similar insight into whether a plausibility preview benefit is due to readers encoding a plausible parafoveal word into their representation of the sentence meaning in place of the target word.

The animal detection task used in Experiment 1A required a response to every question. Such comprehension demands have been shown to yield a more cautious reading strategy that may modulate parafoveal processing (Wotschack & Kliegl, 2013). To confirm that the results of Experiment 1A were not specific to the high comprehension demands, a separate group of participants completed Experiment 1B under the more typical task requirements to respond to occasional comprehension questions.

Method

Participants

Seventy-eight students (mean age = 19.5 years) from the University of Sydney participated in exchange for course credit (38 in Exp. 1A, 40 in Exp. 1B). All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and reported that English was their first language.

Materials and design

The critical stimuli were 80 sentences (M = 13.3 words) in which the preview of a four- to six-letter target word was manipulated (see Table 1 for the stimulus characteristics). Prior to the reader making a saccade across an invisible boundary at the end of the pretarget word (M = 5.5 letters), one of five preview words occupied the target location: (1) identical to the target; (2) a plausible neighbor—an acceptable continuation of the sentence that differed from the target by a single, noninitial letterFootnote 1; (3) an implausible neighbor—a semantically and/or syntactically implausible word, given the prior context, that was a neighbor of the target; (4) a plausible unrelated word—an acceptable sentence continuation that was orthographically unrelated to the target; or (5) an implausible unrelated word—an implausible sentence continuation that was unrelated to the target. The plausible previews were selected to be compatible with both the pre- and posttarget contexts. All sentences appeared in all preview conditions across five counterbalanced lists, interspersed with 30 filler sentences.

Stimulus norming

A separate group of 20 participants completed a cloze norming task in which they were given each sentence frame up to and including the pretarget word and asked to generate the most likely continuation of the sentence. The results confirmed that the target/preview words were not predictable (see Table 1).

Two additional groups of participants provided plausibility ratings on a 5-point scale for the sentence frames up to and including the target/preview word (n = 22), or for the whole sentence including each of the target/preview words (n = 18). The fragments/sentences containing the target, the plausible neighbor, and the plausible unrelated previews were rated as highly acceptable and did not differ significantly from one another (all ts < 1.17, ps > .245). Both the implausible previews were rated significantly lower in acceptability than each of the plausible previews (all ts > 18.45, ps < .001), but the small differences in mean plausibility ratings between the implausible neighbor and implausible unrelated previews were also significant [fragment, t(79) = 3.23, p = .001; sentence, t(79) = 3.62, p = .001].

Apparatus and procedure

Participants’ eye movements were recorded by an EyeLink 1000 as they read sentences on a ViewSonic 225fb CRT monitor with a refresh rate of 150 Hz. The sentences occupied a single line and were presented in black, monospaced font on a gray background. Viewing was binocular, but fixation position was monitored from the right eye. A chin and forehead rest minimized participants’ head movements at a distance of 60 cm from the monitor. At this distance, 2.5 characters subtended 1 deg of visual angle.

Participants were instructed to read the sentences for meaning and to respond to comprehension questions when they appeared. The participants in Experiment 1A were told they would be asked whether or not each sentence contained an animal. At the beginning of the experiment, a three-point calibration procedure was followed by three practice trials with comprehension questions (and a further three practice trials with animal word probes in Exp. 1A). The 80 experimental and 30 filler sentences were then presented in random order. At the beginning of each trial, a fixation point occupied the location of the first letter of the sentence. The sentence was displayed when the participant had made a stable fixation on this point, or a new calibration procedure was performed if necessary. The mean calibration error was less than 0.3 deg of visual angle. On all filler trials in both experiments, the sentence was followed by a multiple-choice comprehension question that required a moderate understanding of the meaning of the sentence. In Experiment 1A, the experimental sentences were followed by the question: “Did this sentence contain an animal(s)?”

Results

Fixations below 80 ms that were within one letter space of an adjacent fixation were merged with that fixation, and the remaining fixations below 80 ms or above 1,000 ms were eliminated (6.3 % of fixations). Trials were discarded if there was a blink immediately before or after a fixation on the target (3.7 % of trials) or if the display change completed more than 10 ms into a fixation or was triggered by a saccade landing to the left of the boundary (12.2 % of trials). Gaze and go-past durations above 2,000 ms and total durations above 4,000 ms were also excluded (nine trials). These exclusions left 5,240 trials (84.0 % of the data) available for analysis.

The following reading measures were analyzed: first fixation duration (the duration of the first fixation on the target, regardless of the number of fixations it received), single fixation duration (the fixation duration when only one first-pass fixation was made on the target), gaze duration (the sum of all first-pass fixations on the target), go-past duration (the sum of all fixations from the first fixation on the target until a word to the right was fixated, including regressions to words earlier in the sentence), and total duration (the sum of all fixations on the target, including regressions from later in the sentence). Measures of the probability of making a first-pass fixation on the target, the probability of regressions out of the target to words earlier in the sentence, and regressions in to the target from words later in the sentence were also analyzed. The means for each of these measures are presented in Table 2.

The data were analyzed by (generalized) linear mixed-effects models (LMM) using the lme4 package (Version 1.1-10; Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015) in R (Version 3.2.2; R Development Core Team, 2015). The models included subject and item random intercepts and random slopes for the preview effects. Four planned contrasts were tested: (1) identical preview benefit—identical preview versus the average of the nonidentical previews; (2) a plausibility effect—the average of the two plausible (nonidentical) versus the average of the two implausible previews; (3) a relatedness effect—the average of the two related versus the average of the two unrelated previews; and (4) the Plausibility × Relatedness interaction.

The major analyses were conducted on the pooled data from Experiments 1A and 1B and included a sum-coded contrast assessing the effect of experiment and its interactions with the preview effect contrasts. Estimates yielding t/z values greater than |1.96| were interpreted as significant at the .05 alpha level. Coefficients, standard errors, and t/z values from the (G)LMMs are reported in Tables 3 and 4. Separate LMMs for the two subexperiments were also conducted, to confirm that they yielded the same pattern of significant results. Unless noted, the pattern of significant effects in the combined analysis was identical to that obtained in each individual experiment.

Eye movement data

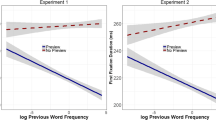

The preview effects are summarized in Fig. 2. We observed a significant identical preview benefit across all duration measures (all ts > 5.1). Readers were also less likely to fixate the target (z = 4.0) and less likely to regress from the target to earlier in the sentence (z = 4.2) after an identical preview. Regressions in did not differ significantly between the identical and nonidentical conditions (z = 1.8).

Preview plausibility significantly affected all first-pass measures. Fixation durations on the target were shorter after plausible than after implausible previews (all ts > 3.5). When the preview was a plausible word, participants were also less likely to fixate the target (z = 3.8)Footnote 2 and less likely to regress from the target (z = 2.7). However, no plausibility preview benefit on total durations was observed (t = –1.4), because readers were significantly more likely to regress to the target when the preview was a plausible word (z = –5.9). Thus, the plausibility preview benefit was restricted to first-pass reading because it was counteracted by late rereading of the target.

Preview orthographic relatedness affected all duration measures. Relative to an unrelated preview, fixation durations were significantly shorter following a neighbor preview (all ts > 1.98). Relatedness did not affect the first-pass fixation rate (z < 1), but readers were less likely to regress out of the target to earlier in the sentence when the preview was related to the target (z = 3.9). Relatedness had no effect on regressions back to the target (z < 1). Thus, in contrast to the effect of preview plausibility, the orthographic preview benefit affected reading from when the target word was first fixated until the reader moved past it.

The Plausibility × Relatedness interaction did not approach significance on any measure (all |t|s and |z|s < 1.7).

In summary, we found a significant effect of preview plausibility on first-pass reading measures and a significant effect of preview–target relatedness on all fixation duration measures. However, these two factors did not interact on any measure, suggesting that they reflect two independent processes.

Between-experiment differences

The only significant main effect of experiment was on late rereading: Experiment 1A, in which participants were required to detect the presence of animal words in addition to responding to occasional comprehension questions, was associated with higher total fixation durations (t = –3.2), because of a higher rate of regressions back to the target (z = –2.3). These late effects presumably reflect a more cautious reading strategy in response to the increased comprehension demands of Experiment 1A. However, experiment had no effect on any first-pass measure (all |t|s and |z|s < 1.7).

The only evidence of a significant difference in preview effects between experiments was a Relatedness × Experiment interaction for go-past duration (t = 2.7). Although larger in Experiment 1A, the relatedness effect was significant in both experiments (1A: b = 62.22, SE = 10.31, t = 6.04; 1B: b = 21.43, SE = 9.86, t = 2.17).

Thus, although the higher comprehension demands of Experiment 1A led to a somewhat more cautious reading strategy, the overall patterns of results were very similar in both experiments,Footnote 3 providing independent replications of the critical additive effects of plausibility and relatedness.

Comprehension analyses

Accuracy for the filler sentence comprehension questions was high (96.1 %, range 80 %–100 %) and did not differ between Experiments 1A (M = 96.4 %) and 1B (M = 95.8 %), t < 1.

The animal detection task in Experiment 1A was designed to check whether the preview or target word had been encoded into the participant’s representation of the sentence meaning. The correct response was “Yes” when the target was an animal, and “No” when the target was a nonanimal. False alarms to nonanimal targets preceded by animal previews (or misses for the reverse arrangement) would suggest that the preview was occasionally encoded instead of the target word.

As is summarized in Table 2, the mean accuracy at detecting whether or not the target was an animal word was very high in all preview conditions. To assess how this was affected by whether or not participants had fixated the target, the GLMM model conducted on the accuracy data included first-pass fixation probability, the probability of regressing back to the target word (both coded as a sum contrasts), and their interactions with the preview contrasts. Accuracy was equally high for related and unrelated previews (z < 1), providing no evidence that readers misperceived the preview as the target word. Preview plausibility did have a significant effect on target detection accuracy, suggesting that readers were more likely to encode the preview instead of the target when it was a plausible continuation of the sentence (z = 4.0). However, a significant interaction with first-pass fixation probability revealed that the plausibility effect on preview encoding was restricted to cases in which the reader skipped the target word (z = –2.7). We also found a Plausibility × Regression interaction, because the plausibility effect was only observed when there was no regression to the target word (z = –3.1).

These findings converge with those of Schotter and Jia (2016) in showing that, despite the significant plausibility preview benefit on all first-pass measures, participants only appeared to incorporate plausible preview words into their representation of sentence meaning in place of the target word on trials in which they never directly fixated the target.

Discussion

We investigated whether preview–target orthographic relatedness modulates plausibility preview effects, to shed light on the mechanisms underlying parafoveal preview benefit. The results replicated earlier evidence that a plausible preview benefits first-pass reading, relative to an implausible preview (Veldre & Andrews, 2016a). We also observed robust effects of preview–target orthographic relatedness on all reading measures. These two factors produced strictly additive effects, suggesting that the benefits of preview plausibility and preview–target orthographic overlap are due to independent processes: a semantic benefit (and/or cost) from the fit of the preview with the context, and an orthographic effect due to overlap (or discrepancy) between the preview and target. The proposed mechanisms underlying these independent contributions to preview effects are discussed below.

As elaborated by Veldre and Andrews (2016a), the effects of preview plausibility are compatible with the mechanisms that Schotter et al. (2014) proposed to account for semantic preview benefits in E-Z Reader 10 (Reichle, Warren, & McConnell, 2009). Central to this account is the assumption that the coordination between lexical processing and saccadic planning operates equivalently under normal reading conditions and in the boundary paradigm. Parafoveal information contributes to both lexical processing of the upcoming word and saccadic planning through adaptive reprogramming of saccades to allow skipping of upcoming words that are partially identified in the parafovea (completion of L 1 ). Critically, because saccades can only be reprogrammed during an early, labile stage, parafoveal words will sometimes be identified after the point at which a saccade to the target word can be modified. Unlike normal reading, however, in the boundary paradigm, the parafoveal preview provides misleading information about the upcoming word that can result in the reader programming a saccade away from the target on the basis of the information extracted from the preview rather than the target. This can produce an apparent preview benefit on target fixations that is due to a saccade planned before visual information from the target became available to the reading system. When the preview is an acceptable continuation of the sentence, the saccade out of the target will be executed. However, when the preview is implausible, failure of the postlexical integration processes that follow identification of the preview cancels the planned saccade, leading to an increased fixation duration on the target.

Consistent with previous evidence of a plausibility preview benefit (Schotter & Jia, 2016; Yang et al., 2014), the effect did not extend to total fixation duration because the early benefit for plausible previews was counteracted by a higher rate of regressions to the target after a plausible than after an implausible preview, even though the plausible previews were always compatible with the posttarget text. Thus, plausible previews yield a trade-off between shorter fixation durations during first-pass reading, but longer second-pass reading. The likely source of the late interference is that competition due to orthographic discrepancies between the preview and target words caused a “double-take.” For plausible previews, this was observed on second-pass reading because the forward saccade from the target location, planned on the basis of preview processing, was not cancelled by postlexical processing failure. In these cases, a regression back to the target word resulted in the target word replacing the preview that had originally been encoded in the representation of sentence meaning, accounting for the lack of a plausibility effect for trials with a regression in the animal detection task in Experiment 1A.

Although the sequence of events described above is broadly compatible with the processing assumptions of E-Z Reader, simulations suggested that the conditions required to observe plausibility preview effects occur relatively rarely. Schotter et al.’s (2014) simulations estimated that processing of parafoveal words had advanced to the L 2 stage (lexical access) on only 8 % of trials, and the likelihood of completing the postlexical processing stage (I) required to generate contextually based semantic preview effects would be even lower. The rarity of the sequence of events necessary to observe parafoveal semantic processing in E-Z Reader contrasts with the robust effects of preview plausibility observed by Veldre and Andrews (2016a) and in the present data. The mechanisms accounting for postlexical effects in E-Z Reader are relatively rudimentary and unexplored. Plausibility preview effects provide a novel source of evidence that will contribute to further refinement of this, and other, eye movement models.

The other critical finding is that, in tandem with plausibility preview effects, the results also showed a robust effect of the orthographic similarity of the preview and target. We found no evidence of the interaction between plausibility and relatedness on eye movements, or the increased animal detection accuracy for target words preceded by orthographically similar previews, that would be expected if plausibility effects were due to misperception of the preview as the orthographically similar target. This suggests that the source of the relatedness effect lies in sublexical processing of words in the parafovea that occurs independently of any subsequent preview processing required to yield a plausibility effect. This is consistent with evidence that orthographic preview benefit is due to abstract letter codes shared by the preview and target that are activated early in the processing of a parafoveal preview, regardless of the preview’s lexical status (see Schotter et al., 2012). The present data indicate that, independently of its contextual fit, activation of the sublexical components of the preview enhances the speed of processing the target word when it replaces the preview, to yield an orthographic preview benefit.

The significant orthographic relatedness effect in the present data contrasts with the lack of a semantic relatedness effect in our earlier work (Veldre & Andrews, 2016a). This is consistent with the sublexical-integration account described above. The lack of orthographic overlap between semantically related previews and targets in the earlier study meant that there was no benefit to target word identification relative to a semantically unrelated (but equally orthographically dissimilar) preview.

Overall, the present study provides evidence of two distinct mechanisms underlying preview benefits. The plausibility preview effect indicates that parafoveal processing is sensitive to the contextual compatibility of the word in the sentence. However, readers also benefit from the orthographic information extracted from a parafoveal preview, due to integration of sublexical features with the target word.

Notes

In 57.5 % of the items, the replacement letter occurred in the same location for the plausible and implausible neighbors (i.e., either both medial or both final letter replacements). The proportions of medial and final replacements were also similar for both the plausible and implausible neighbor previews (75 % vs. 65 % medial replacements, respectively).

Effects of plausibility have typically not been observed as early in the time-course as skipping (see, e.g., Abbott & Staub, 2015). Although statistically significant in the present data, the effect was small (~4 %). Supplementary analyses revealed that the effect was restricted to four-letter targets (b = 0.41, SE = 0.11, z = 3.60) and that there was no effect of plausibility on the fixation probability of longer targets (b = 0.18, SE = 0.13, z = 1.39). Further research will be necessary to establish the conditions under which parafoveal plausibility can affect skipping.

There were some minor differences in the patterns of significance for individual effects between experiments. The identical preview effect on first-pass fixation probability was not significant in Experiment 1A (z < 1), and no preview effects on regressions out emerged in Experiment 1B (all |z|s < 1.43). The plausibility effect on first fixation duration was only marginally significant in Experiment 1B (t = 1.93). The relatedness effect on total duration reached significance in the combined analysis, but not in the separate LMMs for each experiment (ts < 1.92). All other reported effects were significant in both experiments.

References

Abbott, M. J., & Staub, A. (2015). The effect of plausibility on eye movements in reading: Testing E-Z Reader’s null predictions. Journal of Memory and Language, 85, 76–87.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. doi:10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Hohenstein, S., & Kliegl, R. (2014). Semantic preview benefit during reading. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40, 166–190.

R Development Core Team. (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from www.R-project.org

Rayner, K. (1975). The perceptual span and peripheral cues in reading. Cognitive Psychology, 7, 65–81.

Rayner, K., Schotter, E. R., & Drieghe, D. (2014). Lack of semantic parafoveal preview benefit in reading revisited. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21, 1067–1072. doi:10.3758/s13423-014-0582-9

Reichle, E. D., Warren, T., & McConnell, K. (2009). Using E-Z Reader to model the effects of higher level language processing on eye movements during reading. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 1–21. doi:10.3758/PBR.16.1.1

Schotter, E. R. (2013). Synonyms provide semantic preview benefit in English. Journal of Memory and Language, 69, 619–633.

Schotter, E. R., Angele, B., & Rayner, K. (2012). Parafoveal processing in reading. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 74, 5–35. doi:10.3758/s13414-011-0219-2

Schotter, E. R., & Jia, A. (2016). Semantic and plausibility preview benefit effects in English: Evidence from eye movements. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/xlm00002812

Schotter, E. R., Lee, M., Reiderman, M., & Rayner, K. (2015). The effect of contextual constraint on parafoveal processing in reading. Journal of Memory and Language, 83, 118–139.

Schotter, E. R., Reichle, E. D., & Rayner, K. (2014). Rethinking parafoveal processing in reading: Serial-attention models can explain semantic preview benefit and N + 2 preview effects. Visual Cognition, 22, 309–333.

Slattery, T. J. (2009). Word misperception, the neighbor frequency effect, and the role of sentence context: Evidence from eye movements. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 35, 1969–1975. doi:10.1037/a0016894

Sternberg, S. (1969). Memory-scanning: Mental processes revealed by reaction-time experiments. American Scientist, 57, 421–457.

Veldre, A., & Andrews, S. (2016a). Is semantic preview benefit due to relatedness or plausibility? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 42, 939–952. doi:10.1037/xhp0000200

Veldre, A., & Andrews, S. (2016b). Semantic preview benefit in English: Individual differences in the extraction and use of parafoveal semantic information. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 42, 837–854. doi:10.1037/xlm0000212

Wotschack, C., & Kliegl, R. (2013). Reading strategy modulates parafoveal-on-foveal effects in sentence reading. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 66, 548–562. doi:10.1080/17470218.2011.625094

Yang, J., Li, N., Wang, S., Slattery, T. J., & Rayner, K. (2014). Encoding the target or the plausible preview word? The nature of the plausibility preview benefit in reading Chinese. Visual Cognition, 22, 193–213.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Veldre, A., Andrews, S. Parafoveal preview benefit in sentence reading: Independent effects of plausibility and orthographic relatedness. Psychon Bull Rev 24, 519–528 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-016-1120-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-016-1120-8