Abstract

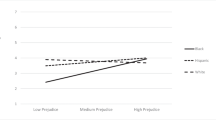

Prior research regarding the influence of face structure on character judgments and first impressions reveals that bias for certain face-types is ubiquitous, but these studies primarily used decontextualized White faces for stimuli. Given the disadvantages Black men face in the legal system, this study aimed to investigate whether the criminal face-type presented in the context of crime influenced different legal system-type judgments as a function of perpetrator race. In a mixed-model design, participants saw Black and White computer-generated faces that varied in criminality presented with either violent or nonviolent crime scenarios. At test, participants attempted to identify the original perpetrator from a photo array, along with providing penalty severity judgments for the crime committed. Results indicate that when crimes were violent, participants meted harsher penalties overall to Black faces or to high-criminality faces identified as the perpetrator. Furthermore, for violent crimes, participants were more likely to select a face from the photo array that was higher/equally as high in criminality rating relative to the actual perpetrator when memory failed or when the perpetrator was Black. Overall, the findings suggest that when people are making judgments that could influence another’s livelihood, they may rely heavily on facial cues to criminality and the nature of the crime; and this is especially the case for Black faces presented in the context of violent crime. The pattern of results provides further support for the pervasive stereotype of Black men as criminal, even in our racially diverse sample wherein 36% identified as Black.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available on the Open Science Framework (OSF) at: https://osf.io/b2dca/.

Code availability

All code for data analysis for the current study are publicly available via the OSF link.

Notes

Note that the criminal face model has also been validated for faces that only vary in shape but not in reflectance (Funk et al., unpublished data), which is especially relevant for the present study in which a target’s skin color remains constant across conditions.

Participants did not differ in prejudiced views. Thus, individual differences were excluded from analyses.

For completion, the model results for the nonviolent crime-type condition can be found in Appendix C.

References

Arendt, F., Steindl, N., & Vitouch, P. (2015). Effects of news stereotypes on the perception of facial threat. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 27(2), 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000132

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Blair, I. V., Judd, C. M., & Fallman, J. L. (2004). The Automaticity of race and Afrocentric facial features in social judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(6), 763–778. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.763

Bornstein, B. H., Rung, L. M., & Miller, M. K. (2002). The effects of defendant remorse on mock juror decisions in a malpractice case. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 20(4), 393–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.496

Brown, K. T. (2006). Review of Black demons: The media’s depiction of the African American male criminal stereotype. Journal of Black Psychology, 32(2), 243–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798406286802

Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2016). FY 2016 persons arrested and booked [Data set]. The U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved September 23, 2019 from https://www.bjs.gov

Crandall, C. S., Eshleman, A., & O’Brien, L. (2002). Social norms and the expression and suppression of prejudice: The struggle for interrnalization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(3), 359–378. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.3.359

Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.757

Dukes, K. N., & Gaither, S. E. (2017). Black racial stereotypes and victim blaming: Implications for media coverage and criminal proceedings in cases of police violence against racial and ethnic minorities. Journal of Social Issues, 73(4), 789–807. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12248

Eberhardt, J. L., Goff, P. A., Purdie, V. J., & Davies, P. G. (2004). Seeing black: Race, crime, and visual processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(6), 876–893. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01716.x

Eberhardt, J. L., Davies, P. G., Purdie-Vaughns, V. J., & Johnson, S. L. (2006). Looking deathworthy: Perceived stereotypicality of Black defendants predicts capital-sentencing outcomes. Psychological Science, 17(5), 383–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01716.x

Ferguson, H. S., Owen, A., Hahn, A. C., Torrance, J., DeBruine, L. M., & Jones, B. C. (2019). Context-specific effects of facial dominance and trustworthiness on hypothetical leadership decisions. PLOS ONE, 14(7), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214261

Flowe, H. D. (2012). Do characteristics of faces that convey trustworthiness and dominance underlie perceptions of criminality? PLOS ONE, 7(6), 1–7.

Flowe, H. D., & Humphries, J. E. (2011). An examination of criminal face bias in a random sample of police lineups. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(2), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1673

Funk, F., Walker, M., & Todorov, A. (2017). Modelling perceptions of criminality and remorse from faces using a data-driven computational approach. Cognition and Emotion, 31(7), 1431–1443. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1227305

Gold, G. J., & Weiner, B. (2000). Remorse, confession, group identity, and expectancies about repeating a transgression. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 22(4), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324834BASP2204_3

Jaeger, B., Todorov, A. T., Evans, A. M., & van Beest, I. (2020). Can we reduce facial biases? Persistent effects of facial trustworthiness on sentencing decisions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 90, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2020.104004

Jones, C. S., & Kaplan, M. F. (2003). The effects of racially stereotypical crimes on juror decision-making and information-processing strategies. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 25(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324834BASP2501_1

Klatt, T., Maltby, J., Humphries, J. E., Smailes, H. L., Ryder, H., Phelps, M., & Flowe, H. D. (2016). Looking bad: Inferring criminality after 100 ms. Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice, 12(2), 114–125.

Klatzky, R. L., Martin, G. L., & Kane, R. A. (1982). Semantic interpretation effects on memory for faces. Memory & Cognition, 10(3), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03197630

Kleider, H. M., Cavrak, S. E., & Knuycky, L. R. (2012). Looking like a criminal: Stereotypical Black facial features promote face source memory error. Memory & Cognition, 40(8), 1200–1213. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-012-0229-x

Kleider-Offutt, H. M. (2019). Afraid of one afraid of all: When threat associations spread across face-types. Journal of General Psychology, 146(1), 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2018.1540397

Kleider-Offutt, H. M., Bond, A. D., & Hegerty, S. E. A. (2017). Black stereotypical features: When a face type can get you in trouble. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(1), 28–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416667916

Kleider-Offutt, H. M., Knuycky, L. R., Clevinger, A. M., & Capodanno, M. M. (2017). Wrongful convictions and prototypical Black features: Can a face-type facilitate misidentifications? Legal and Criminological Psychology, 22(2), 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12105

Kleider-Offutt, H. M., Bond, A. D., Williams, S. E., & Bohil, C. J. (2018). When a face type is perceived as threatening: Using general recognition theory to understand biased categorization of Afrocentric faces. Memory & Cognition, 46(5), 716–728. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-018-0801-0

Kleider-Offutt, H., Meacham, A. M., Branum-Martin, L., & Capodanno, M. (2021). What’s in a face? The role of facial features in ratings of dominance, threat, and stereotypicality. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 6, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00319-9

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Gulliford Press.

Knuycky, L. R., Kleider, H. M., & Cavrak, S. E. (2014). Line-up misidentifications: When being “prototypically Black” is perceived as criminal. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2954

Kovera, M. B. (2019). Racial disparities in the criminal justice system: Prevalence, causes, and a search for solutions. Journal of Social Issues, 75(4), 1139–1164. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12355

Lucas, C. A., Brewer, N., & Palmer, M. A. (2021). Eyewitness identification: The complex issue of suspect-filler similarity. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 27(2), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000243.supp(Supplemental)

MacLin, M. K., & Herrera, V. (2006). The criminal stereotype. North American Journal of Psychology, 8(2), 197–208.

MacLin, O. H., & MacLin, M. K. (2004). The effect of criminality on face attractiveness, typicality, memorability and recognition. North American Journal of Psychology, 6(1), 145–154.

Mancini, C., Mears, D. P., Stewart, E. A., Beaver, K. M., & Pickett, J. T. (2015). Whites’ perceptions about Black criminality: A closer look at the contact hypothesis. Crime & Delinquency, 61(7), 996–1022. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128712461900

Mazur, A., Mazur, J., & Keating, C. (1984). Military rank attainment of a West Point class: Effects of cadets’ physical features. American Journal of Sociology, 90(1), 125–150. https://doi.org/10.1086/228050

Mitchell, T. L., Haw, R. M., Pfeifer, J. E., & Meissner, C. A. (2005). Racial Bias in Mock Juror Decision-Making: A Meta-Analytic Review of Defendant Treatment. Law and Human Behavior, 29(6), 621–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-005-8122-9

Montepare, J. M., & Zebrowitz, L. A. (1998). Person perception comes of age: The salience and significance of age in social judgments. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 93–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60383-4

Mueller, U., & Mazur, A. (1998). Reproductive constraints on dominance competition in male Homo Sapiens. Evolution and Human Behavior, 19(6), 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-5138(98)00032-4

Oliver, M. B., & Fonash, D. (2002). Race and crime in the news: Whites’ identification and misidentification of violent and nonviolent criminal suspects. Media Psychology, 4(2), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0402_02

Olivola, C. Y., Funk, F., & Todorov, A. (2014). Social attributions from faces bias human choices. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(11), 566–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.09.007

Oosterhof, N. N., & Todorov, A. (2008). The functional basis of face evaluation. PNAS, 105(32), 11087–11092. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0805664105

Pipes, R. B., & Alessi, M. (1999). Remorse and a previously punished offense in assignment of punishment and estimated likelihood of a repeated offense. Psychological Reports, 85(1), 246–248. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1999.85.1.246

Porter, S., & ten Brinke, L. (2009). Dangerous decisions: A theoretical framework for understanding how judges assess credibility in the courtroom. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 14, 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532508X281520

R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Rumsey, M. C. (1976). Effects of defendant background and remorse on sentencing judgments. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 6(1), 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1976.tb01312.x

SegrestPurkiss, S. L., Perrewé, P. L., Gillespie, T. L., Mayes, B. T., & Ferris, G. R. (2006). Implicit sources of bias in employment interview judgments and decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101(2), 152–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.06.005

Sigall, H., & Ostrove, N. (1975). Beautiful but dangerous: Effects of offender attractiveness and nature of the crime on juridic judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31(3), 410–414. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076472

Skorinko, J. L., & Spellman, B. A. (2013). Stereotypic crimes: How group-crime associations affect memory and (sometimes) verdicts and sentencing. Victims & Offenders, 8(3), 278–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2012.755140

Sommers, S. R., & Ellsworth, P. C. (2001). White juror bias: An investigation of prejudice against Black defendants in the American courtroom. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 7(1), 201–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8971.7.1.201

Stewart, J. E., II. (1985). Appearance and punishment: The attraction-leniency effect in the courtroom. The Journal of Social Psychology, 125(3), 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1985.9922900

Todorov, A., Mandisodza, A. N., Goren, A., & Hall, C. C. (2005). Inferences of competence from faces predict election outcomes. Science, 308(5728), 1623–1626. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1110589

Uleman, J. S., Blader, S. L., & Todorov, A. (2005). Implicit impressions. In R. R. Hassin, J. S. Uleman, & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The new unconscious (pp. 362–392). Oxford University Press.

Vokey, J. R., Baker, J. G., Hayman, G., & Jacoby, L. L. (1986). Perceptual identification of visually degraded stimuli. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 18(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03200985

Wang, X., Guinote, A., & Krumhuber, E. G. (2018). Dominance biases in the perception and memory for the faces of powerholders, with consequences for social inferences. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 78, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2018.05.003

Willis, J., & Todorov, A. (2006). First impressions: Making up your mind after a 100-ms exposure to a face. Psychological Science, 17(7), 592–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01750.x

Wixted, J. T., & Wells, G. L. (2017). The relationship between eyewitness confidence and identification accuracy: A new synthesis. Psychology Science in the Public Interest, 18(1), 10–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100616686966

Wuensch, K. L., Castellow, W. A., & Moore, C. H. (1991). Effects of defendant attractiveness and type of crime on juridic judgment. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 6(4), 714–724.

Yang, Q., Zhu, B., Zhang, Q., Wang, Y., Hu, R., Liu, S., & Sun, D. (2019). Effects of male defendants’ attractiveness and trustworthiness on simulated judicial decisions in two different swindles. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02160

Zebrowitz, L. A., Wadlinger, H. A., Luevano, V. X., White, B. M., Xing, C., & Zhang, Y. (2011). Animal analogies in first impressions of faces. Social Cognition, 29(4), 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2011.29.4.486

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support were received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ashley M. Meacham: Methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, project administration. Heather M. Kleider-Offutt: Conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, supervision. Friederike Funk: Resources, writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the Human Research Ethics committee of Georgia State University (Ethics approval number: H20336).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Practices Statement

The data and analysis script for all experiments are publicly available (https://osf.io/b2dca/) and the study was not preregistered.

Appendices

Appendix A

Face criminality pre-ratings

The overall model predicting criminality ratings was significant (χ2(2) = 501.72, p < 0.001; Table 6). As expected, low-criminality faces were judged as significantly less criminal than neutral criminality faces (b = -0.34, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI [-0.43, -0.25]), while high-criminality faces were judged as significantly more criminal than neutral criminality faces (b = 0.73, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.63, 0.82]).

Appendix B

Sample vignettes for violent crimes

Stereotypically White crime – “Police got a call Tuesday night from a local woman about a house fire. The firefighters were on the scene before the house was too damaged, although the front door and garage were both severely burned. Luckily the woman got herself and her pets out of the house quickly, and no one was hurt. Home video surveillance showed the woman’s ex-boyfriend setting the fire. Police are currently looking for her ex-boyfriend as he seemed to have disappeared following the fire. They have a warrant out for his arrest on the charge of arson.”

Stereotypically Black crime – “Last night, a man walked into a convenience store with a gun in his pocket. After grabbing a six-pack of beer, the perpetrator walked to the cash register as if he was going to pay. While the cashier was ringing up the man for the beer, the man pulled out his gun and directed the cashier to empty the register into a bag. The cashier complied, and the man left the store. The police were promptly called and are looking for the assailant. The entire ordeal was caught on camera, and police are hopeful that the criminal will be found.”

Sample vignettes for nonviolent crimes

Stereotypically White crime – “Early this morning police arrested a local man forwarded appears to be a case of insurance fraud. The house mysteriously burned down a few days back with no apparent explanation. Authorities now believe it was done on purpose by the owner. Neighbors told police that the man had recently started to have severe money problems and could no longer afford to pay the mortgage on his home, which had caused his wife to take the children and leave him. Police believe that he thought that insurance would cover the cost of the damages, and he would no longer be liable to pay his mortgage.”

Stereotypically Black crime – “On the night of July 17th at approximately 9:45 pm police received a call regarding a car theft in a local mall parking lot. According to police, employees witnessed a man wearing a hoodie and pants using what they believe to be a metal wire to unlock the driver's side door. After gaining access to the vehicle the assailant then sped off almost striking one of the employees who happened to witness the apparent theft. Witnesses claim that the suspect may have been under the influence because of how erratically he was driving through the parking lot.”

Vignette violence pre-ratings

The overall model predicting vignette violence ratings was significant (χ2(2) = 521.47, p < 0.001; Table 8). Violent crimes were rated as significantly more violent than nonviolent crimes (b = 2.08, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001, 95% CI [1.92, 2.24]), while pre-determined, stereotypically Black crimes did not significantly differ from stereotypically White crimes in violence ratings.

Black perpetrator expectations pre-ratings

The overall model predicting expectations that a crime would be committed by a Black man was significant (χ2(1) = 76.74, p < 0.001; Table 9). Expectations that a crime would be committed by a Black man were significantly higher for pre-rated stereotypically Black, compared to White, crimes (b = 0.53, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.41, 0.65]).

White perpetrator expectations pre-ratings

The overall model predicting expectations that a crime would be committed by a White man was significant (χ2(1) = 76.74, p < 0.001; Table 10). Expectations that a crime would be committed by a White man were significantly higher for pre-rated stereotypically White, compared to Black, crimes (b = 0.57, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.46, 0.68]).

Assigned penalty severity pre-ratings

The overall model predicting the severity of assigned penalties for a crime was significant (χ2(1) = 179.57, p < 0.001; Table 11). Violent crimes were given much harsher penalties than nonviolent crimes (b = 1.01, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.87, 1.16]).

Appendix C

Identification in the nonviolent crime condition

The overall model was not significant (χ2(4) = 3.15, p > 0.05; Table 12), suggesting that our model predictors do not reliably influence the face-type level chosen as the perpetrator of nonviolent crimes. Hit and false alarm rates and associated confidence in identification for Black and White perpetrator trials in the nonviolent crime condition are presented in Table 13.

Appendix D

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Meacham, A.M., Kleider-Offutt, H.M. & Funk, F. Looking more criminal: It’s not so black and white. Mem Cogn 52, 146–162 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-023-01451-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-023-01451-1