Abstract

The revelation effect is a robust phenomenon in episodic memory whereby stimuli that immediately follow a simple cognitive task are more likely to garner positive responses on a variety of memory tests, including autobiographical memory judgments. Six experiments investigated the revelation effect for judgments of past and future events as well as judgments made from others’ perspectives. The purpose of this work was to determine whether these subjectively distinct judgments are subject to the same decision-making biases, as might be expected if they are governed by similar processes (e.g., Schacter, Addis, & Buckner 2007). College-aged participants were asked to rate a variety of life events according to whether the events had occurred during their childhoods or would occur during the next 10 years. Events that followed an anagram task were judged as more likely to have happened in the past and more likely to occur in the future. We also showed a revelation effect when participants were asked to adopt the perspective of others when making judgments about past and future events. When the task was reworded to be non-episodic (participants judged how common the events were during childhood and adulthood), no revelation effect was found for either past or future time frames, which suggests common boundary conditions for both types of judgments. The results are consistent with studies showing strong parallels between remembering and other forms of self-projection but not with semantic memory judgments.

Similar content being viewed by others

“Like right now…I’m not able to remember what happened earlier. And I’m not thinking about what will happen next. Because I don’t know.”

Geri Taylor (as reported by Kleinfield, 2016).

The quote above is excerpted from a New York Times profile of a woman named Geri Taylor who is adjusting to her recent diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. In the article, Ms. Taylor describes the memory problems that are endemic to the disease (“I am not able to remember what happened earlier”) and also describes difficulties in imagining her future (“I’m not thinking about what will happen next”; Kleinfield, 2016). Ms. Taylor’s impressions of having lost connection with both the past and the future are consistent with a rapidly growing body of research that has uncovered a surprising degree of overlap in the cognitive and neural processes associated with remembering the past and imagining the future.

There is a good deal of evidence that thinking about past events and imagining future events are governed by similar constructive processes (for a review, see Schacter, 2012), engage the same brain networks (e.g., Addis, Wong, & Schacter, 2007; Schacter & Addis, 2007; Szpunar, Watson, & McDermott, 2007; Okuda et al. 2003; for a review see Schacter, Addis, Hassabis, Martin, Spreng, & Szpunar, 2012), and share numerous phenomenological characteristics (e.g., Berntsen & Bohn, 2010; D'Argembeau & Van Der Linden, 2004, 2006; Jarvis & Miller, in press; Spreng & Levine, 2006). Ms. Taylor’s description of her twin difficulties in thinking about the past and the future is consistent with research on other individuals with Alzheimer disease (Addis, Sacchetti, Ally, Budson, & Schacter, 2009), as well as other groups with memory impairments, including older adults (for a review see Schacter, Gaesser, & Addis, 2013), individuals with amnesia (Klein, Loftus, & Kihlstrom, 2002; Hassabis, Kumaran, Vann, & Maguire, 2007), and depression (Williams et al., 1996).

The findings that suggest that past and future thinking depend on similar mechanisms raise the possibility that they will be susceptible to similar memory illusions and biases, and this question motivates the present study. The literature is replete with demonstrations of how easily memory can be biased, distorted, or manufactured entirely (e.g., Bartlett, 1932; Loftus, 1992; Loftus & Pickrell, 1995; Neisser & Harsch, 1992; for a taxonomy, see Brainerd & Reyna, 2005). One of the more mysterious examples of memory biases is the revelation effect. The revelation effect was first described as a phenomenon of recognition memory. In a series of experiments, Watkins and Peynircioğlu (1990) showed that both old and new items on a recognition test were more likely to be classified as “old” if they were first presented in a disguised or incomplete form (e.g., as an anagram or as a word-fragment). The revelation effect has been found to be exceedingly robust, occurring on a variety of episodic memory tasks (Bornstein & Neely, 2001; LeCompte, 1995; Westerman& Greene, 1996), including judgments about childhood events (Bernstein, Godfrey, & Davison, 2004; Bernstein, Whittlesea, & Loftus, 2002). The effect has also been found to generalize across different types of stimuli (Bornstein & Wilson, 2004; Watkins & Peynircioğlu, 1990, Westerman & Greene, 1996), and different participant populations (Guttentag & Dunn, 2003; Thapar & Sniezek, 2008). The first few studies on the phenomenon used revelation tasks that involved manipulating the test item itself (e.g., Watkins & Peynircioğlu, 1990; Peynircioğlu & Tekcan, 1993; Luo, 1993); however, the revelation effect has since been found even when the solved item is not related to the judgment at hand. For instance, unscrambling a word unrelated to the test item produces a revelation effect, as do tasks such as letter counting, memory span tasks (Westerman & Greene, 1998), and math problems (Niewiadomski & Hockley, 2001). An unfilled interval (Westerman & Greene, 1998) does not produce a revelation effect, nor does a simple recopying task (Bornstein & Neely, 2001) (for a recent review, see Aßfalg, 2017).

The revelation effect has proven surprisingly hard to explain. The effect is often described as a decision-making bias because it manifests as an increase in the proportion of “yes” responses to questions that probe episodic memory. However, the mechanism underlying this tendency has not been established (see Aßfalg, Bernstein, & Hockley, 2017, for a meta-analysis and review of theoretical accounts). Briefly, explanations have posited that the higher proportion of positive responses reflects an enhanced sense of familiarity for the to-be judged item either due to misattributed activation of information in memory (Westerman & Greene, 1998) or due to an enhanced sense of fluency for the item that follows a revelation task caused by the relative difficulty of the revelation task (Whittlesea & Williams, 2001b). Another account suggests that the revelation task creates a temporary shift to a more liberal response bias (Hicks & Marsh, 1998), perhaps due to disruption of working memory (Hockley & Niewiadomski, 2001).

The current study is neither intended nor able to disentangle these theories of the revelation effect. Rather, the point of the study is to use the revelation effect as a tool to determine whether comparable effects will be found for tasks that involve making judgments about past and future events to better understand the parallels between remembering and forecasting. Is the mental process of forecasting susceptible to illusion in a manner similar to the remembering process? Will events seem more likely to occur in the future if they are considered immediately following a cognitive task? The answers to these questions are not foregone conclusions. Although the revelation effect is robust, there are cases in which it does not occur (e.g., for semantic memory judgments; Watkins & Peynircioğlu, 1990) and times when it reverses (e.g., for faces; Aßfalg & Bernstein, 2012). Thus, evidence that revelation tasks increase judgments of past autobiographical events (Bernstein et al., 2002) does not necessitate it doing so for future judgments. Indeed, several studies have found that the revelation effect is attenuated when judgments are more likely to be based on recollection, rather than familiarity (Cameron & Hockley, 2000; Mulligan, 2007; Westerman 2000). These prior results suggest that the revelation effect could be larger when judging future events compared with past events, as a recollection would seem unlikely for events that have not yet occurred. On the other hand, there is some evidence that simulating future events is more cognitively demanding than retrieving past events (Addis et al., 2007; Szpunar et al., 2007), which may argue for a smaller revelation effect in the future conditions insofar as such judgments may be less likely to be based on the relatively faster and more automatic processes involved in familiarity assessment.

The present experiments explored the revelation effect in judgments about the past and the future. Participants were asked to judge various life events according to whether they had experienced the event during their childhood or if they would experience the event in the future (Experiments 1 and 2). We also explored a potential boundary condition for these effects by testing for revelation effects when the judgments were not of an episodic nature (Experiments 3, 4, and 5). Finally, in Experiment 6 we extended our findings to a different type of self-projection by asking participants to adopt the perspective of friends when making their judgments.

Experiments 1 and 2

In Experiments 1 and 2, participants rated a series of plausible life events according to whether the events had occurred during their childhoods (past) or would occur in the next 10 years (future). Past versus future judgments were manipulated between participants. Half of the events were immediately preceded by an anagram task (the revelation condition), and half were not (the control condition). In Experiment 1, solutions to the anagrams were words included in the events, and in Experiment 2 solutions to the anagram were words unrelated to the events. We conducted two experiments for two reasons. First, there is some evidence that the effect is based on different processes when the revelation task involves the to-be judged stimulus and when it does not (Leynes, Landau, Walker, & Addante, 2004; Verde & Rotello, 2004). Therefore, we carried out this study using both types of revelation tasks in case conditions could be found in which the two tasks produce dissociable effects. Secondly, it allows an opportunity for replicating the results with different samples and different revelation tasks.

Method

Power analysis

The N of Experiment 1 was determined by a power analysis conducted using g*power (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007). Past research by Bernstein et al. (2002) and our own pilot work with the materials led us to expect a small-to-medium effect of revelation (based on the norms advocated by Cohen, 1988). Although there was reason to think we would find revelation effects for past and future judgments, evidence against this hypothesis would be revealed by an interaction between judgment type (past vs. future) and revelation condition, possibly due to an absence or attenuation of the effect on future judgments. We expected any such interaction to be quite small. The outcome of this power analysis showed that we would need 93 subjects per group to reach 90% power assuming a small effect (we estimated a d =.24, which converts to f =.12; Cohen, 1988) and conservatively estimating a correlation of .5 among repeated measures. We tested 100 participants per group in Experiment 1. Once the results of Experiment 1 were known, we then had an empirical reason to scale back the N in Experiments 2–6) to conserve resources.

Participants

Undergraduate students from Binghamton University participated in exchange for partial credit toward a course requirement. There were 200 participants in Experiment 1 and 110 participants in Experiment 2.

Materials and procedures

The stimuli were 60 events from the Life Events Inventory (Fields & Brown, 2015; Garry, Manning, Loftus, & Sherman, 1996), which lists plausible events that may have happened to a person in his or her life (e.g., fell out of a boat, found a wallet, saw a tornado). Past versus future judgments were manipulated between participants. In Experiment 1, participants were randomly assigned to either a past or a future condition (N = 100 per group). In the past condition, participants saw each event individually and were asked whether the event happened to them prior to the age of 13. A scale was presented in the lower part of the screen that ranged from 1 (definitely did not happen) to 8 (definitely happened). Participants in the future condition were asked to rate whether they believed that the event would happen sometime in the next 10 years (with “1” indicating that the event definitely will not happen and “8” indicating it definitely will happen). Some of the events required minor rewording for the past and future conditions. For instance, “Saw a solar eclipse” was presented in the past condition and “See a solar eclipse” was presented in the future condition.

Half of the events were immediately preceded by an anagram task (the revelation condition), and half were not (the control condition). The revelation condition required participants to solve an anagram before rating the event. In Experiment 1, the anagrammed word was one of the words in the event. For instance, for the revelation condition, the event “Cry at a doctor’s office visit” initially appeared as, “Cry at a doctor's cieffo visit.” The anagrammed words were selected arbitrarily from the nouns and verbs in the event. Anagrams were from 4–9 letters in length, and were never based on the first word in the event. The event (with one of the words as an anagram) appeared in the center of the screen, and the anagram also appeared (alone) on a separate line beneath the event. Just below the anagram, a rule that could be used to solve it was presented. For instance, for the anagram “c i e f f o” the rule “5 4 6 3 2 1” appeared just below it. The numbers in the rule indicated a given letter’s position in the solution. In this example, the 1 appeared below the “o” and was therefore the first letter of the solution. The rule that was used differed depending on the length of the anagram and was the same for every anagram of a given length. Participants were instructed how to use the rule before beginning the experiment. After typing the solution to the anagram, participants pressed the “enter” key, the screen cleared, and then the event appeared again (with all words intact). Participants then made their ratings on the 1–8 scale. When an event was in the control condition, the intact event simply appeared along with the 1–8 scale, and participants rated the event. When we designed the experiment, we intended the order of revealed and control trials to be random; however, while analyzing the data, we learned the trials had actually been presented in blocks of 30 revealed and 30 control trials due to an oversight while creating the program. The revelation versus control condition was counterbalanced such that each event was as likely to appear as a revealed and a control item. In addition, the order of the revealed and control blocks was counterbalanced, so that, across participants, the control and revealed blocks were equally likely to be presented first. After discovering this error, the data were re-analyzed to assure that the order of revealed and control trials had no impact on responses and did not interact with any of the other variables (it did not). We also note that past work on the revelation effect has found that the revelation effect does not depend on randomly ordered revealed and control trials; indeed, the effect occurs even in between-subjects designs (Westerman & Greene, 1996). This oversight did not occur in any of the other experiments in the series, including Experiment 2, which is largely a replication of Experiment 1.

Experiment 2 was identical to Experiment 1 except that the words that were presented as anagrams were unrelated to the words in the event. For instance, for the event, “Saw a solar eclipse,” the event appeared, and then below it (within the same display) an unrelated anagram “b u l c i p e r” (republic) was presented along with its solution rule. After typing the solution, the screen cleared and participants rated the event on either the future or past scale. The events were counterbalanced, such that, across participants, an event was equally likely to be in the revelation and control conditions. The order of revelation and control trials was random, and a different random order was used to present the events to each participant.

Results

Experiment 1

The results of Experiments 1 are summarized in Table 1. The data of two participants were lost due to a computer malfunction. The dependent variable was the ratings to the life events (unlike most revelation effect experiments, there were no targets or lures in this experiment). The remaining participants’ data were analyzed with a two (revelation condition: revealed vs. control) by two (judgment type: past vs. future) mixed factor analysis of variance, conducted on the ratings given to the life events. Revelation condition was manipulated within-subjects and judgment type was manipulated between-subjects. The results showed a main effect of revelation; events that followed the anagram task received higher ratings than events in the control condition, F (1, 196) = 25.11 p < .001 MSE = .21 η2 p = .11. There was not a main effect for the type of judgment, F< 1. There was an interaction between revelation condition and judgment type, F (1, 196) = 4.21 p =.042, MSE = .21, η2 p = .02, with the revelation effect being larger for future judgments in this experiment. We did not predict an effect in this direction, and this interaction, which was just inside the conventional criterion for statistical significance, was not replicated in any of the subsequent studies in this paper, and so we will not consider it further here.

Bayesian analyses of the data supported the conclusion that a revelation effect occurred in this experiment. Collapsing across past and future conditions, the ratings were analyzed with a Bayesian t-test (Rouder, Speckman, Sun, Morey, 2009) via the calculator provided at http://pcl.missouri.edu/bayesfactor. The scaled JZS Bayes Factors showed that the data of Experiments was much more likely to be observed under the alternative hypothesis than the null hypothesis, scaled JZS BF 1 0 = 8451.73.

Experiment 2

The results of Experiment 2 are summarized in Table 1. A two (revelation condition: revealed vs. control) by two (judgment type: past vs. future) mixed factor analysis of variance was conducted on the ratings given to the life events. Revelation condition was manipulated within-subjects and judgment type was manipulated between-subjects. The results were very similar to Experiment 1. There was a main effect of revelation condition; events that were preceded by the anagram task received higher ratings than events in the control condition, F (1, 108) = 18.14, p <.001 MSE = .18 η2 p = .14. There was not a main effect for the type of judgment, F < 1 nor was there an interaction between revelation condition and judgment type, F < 1. A Bayesian t-test of the ratings, collapsed across past and future conditions, supported the conclusions based on the frequentist approach described above. The analysis found that the data were much more likely to be observed under the alternative hypothesis than the null hypothesis, scaled JZS BF 1 0 = 372.67. In summary, a revelation effect was found for both past and future judgments in Experiments 1 and 2. It should be noted that the current results help to rule out a potential alternate interpretation of the result of Bernstein et al. (2002), which showed a revelation effect for childhood memories. In their study (as in ours) participants rated events that happened outside of the purview of the experimental context. It is therefore possible that the revelation task facilitated the retrieval of events that did, in fact, occur during childhood, possibly because the longer recall period afforded by the revelation phase allowed participants to retrieve events that were not immediately accessible (e.g., Payne, 1987). Such a process, while possibly interesting in its own right, would not be an example of a revelation effect, as the revelation effect increases the probability of responding that that event occurred even when it did not. The fact the revelation task produced effects for both past and future events in the present study supports Bernstein et al.’s conclusion that the revelation task indeed elicits illusions similar to what has been found in studies in which the to-be remembered events are presented and tested within the experimental session.

Experiments 3 and 4

As mentioned in the introduction, the revelation effect has been shown to have great generality across memory tasks, revelation tasks, stimuli, and populations. Indeed, the paucity of consistent boundary conditions has made theorizing about this effect a challenge. That said, there is evidence that judgments that draw on semantic memory, rather than episodic memory, are less susceptible to revelation effects. For instance, Watkins and Peynircioğlu (1990) found no revelation effect on category typicality ratings, lexicality judgments, and word frequency judgments. Their results led to the conclusion that the effect is limited to episodic memory judgments. On the other hand, two more recent studies have shown a revelation effect on judgments that do not necessarily draw on episodic memory. Bernstein et al. (2002) found that validity ratings of facts were higher after a revelation task, and Kronlund and Bernstein (2006) found a preference for brand names that were rated after a revelation task.

The next two experiments were designed to see whether the previously established semantic-memory boundary condition would hold for the events used in Experiments 1 and 2 and whether this boundary condition would occur for both past and future judgments. In Experiments 3 and 4, instead of asking participants to rate whether an event happened to them personally, participants were asked to rate how common the events are during childhood (defined as younger than 13 years). Likewise, instead of asking participants whether an event was likely to happen to them in the future, we asked them to judge how common the events are during young adulthood (defined for our participants as ages 24–34 years, and which we verified was a future age range for all of our participants). Half of the judgments were immediately preceded by an anagram task and half were not. In Experiment 3, the anagram was of one of the words in the event that was to be rated and in Experiment 4, the anagram was of an unrelated word.

Method

Participants

One-hundred and three undergraduate students at Binghamton University participated in Experiment 3 and 108 participated in Experiment 4 in exchange for partial credit toward a course requirement. Participants were tested individually.

Materials and procedure

The materials and procedures used in Experiments 3 and 4 were identical to those used in Experiments 1 and 2 with the following exception: Participants in the past condition were asked to rate each item according to how common the event is, generally speaking, during childhood (age <13 years) on a scale of 1 (very uncommon) to 8 (very common). Participants in the future condition were asked to rate how common the events are, generally speaking, during ages 24–34 years. We recorded the ages of all participants, and confirmed that the future age range was older than all of the participants in this experiment. In Experiment 3, the anagram in the revelation condition was one of the words from the life event that was being rated, and in Experiment 4 the anagram was a word unrelated to the event.

Results

Experiment 3

The results of Experiment 3 are summarized in Table 2. A two (revelation condition: revealed vs. control) by two (judgment type: past vs. future) mixed factor analysis of variance was conducted on the ratings given to the life events. Revelation condition was manipulated within-subjects and judgment type was manipulated between-subjects. There was no main effect of revelation condition, F < 1, no main effect for judgment type, F < 1, and no interaction between the variables F < 1. These conclusions were also supported by a Bayesian t-test, which was conducted on the ratings after collapsing across past and future conditions. This analysis yielded a Bayes factor in favor of the null hypothesis. Given the data, the null hypothesis was more than eight times more likely than the alternative hypothesis. Scaled JZS BF 01 = 8.88.

Experiment 4

The results are summarized in Table 2. A two (revelation condition: revealed vs. control) by two (judgment type: past vs. future) mixed factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) conducted on the ratings given to the life events showed no revelation effect, no effect of judgment type, and no interaction between the variables, all Fs <1. The conclusions were confirmed with a Bayesian t-test conducted on the ratings after collapsing across the past and future conditions. Given the observed data, the null hypothesis was more than eight times more likely than the alternative hypothesis, scaled JZS BF 01 = 8.29.

In summary, we did not observe revelation effects for past- or future-based judgments in Experiments 3 and 4. Despite only changing the question from a personal to a general query, the revelation effects observed in Experiments 1 and 2 disappeared. Notably, this finding is in line with the predictions made by theories suggesting a relationship between forecasting and episodic memory based on common neurological substrates (Buckner & Carroll, 2007; Mullally & Maguire, 2014) in that the revelation task influenced forecasting and episodic memory judgments similarly, but did not influence semantic judgments.

Experiment 5

Experiment 5 was conducted to follow up on the null results of Experiments 3 and 4, and represents a brief detour from the primary goal of comparing revelation effects for past and future events. Experiments 3 and 4 failed to produce revelation effects on non-episodic tasks. These results are consistent with the results of four experiments reported by Watkins and Peynircioğlu (1990), but are inconsistent with four other experiments. Bernstein et al. (2002) showed a revelation effect when participants were asked to make true or false judgments on general knowledge statements (e.g., “The leopard is the fastest animal in the world”) after unscrambling either a related or unrelated anagram. In addition, Kronlund and Bernstein (2006) showed that preference ratings from brand names were higher after solving both related and unrelated anagrams. However, in this latter study, an episodic memory judgment immediately preceded each preference judgment, raising the possibility that participants adopted a decision-making strategy for the episodic judgment that carried over to the preference judgment.

Given the mixed results in the literature, we conducted an additional experiment to assess the effect of revelation on a non-episodic memory task. As reviewed above, the experiments that found revelation effects on such tasks asked participants to rate dimensions related to positivity (truth and preference). To see if the revelation effect in non-episodic judgments depends on positivity ratings, in Experiment 5, participants rated life events according to the pleasantness of the experience. Half of the events were preceded by an unmatching anagram task and half were not. We used only unmatching anagrams in Experiment 5 because affective ratings tend to increase due to stimulus repetition alone (i.e., the mere exposure effect; Zajonc, 1968), and we wanted to be sure that the results reflected the effect of the revelation task irrespective of stimulus repetition.

Method

Participants

Ninety-four undergraduate students at Binghamton University participated in exchange for partial credit toward a course requirement. Participants were tested individually.

Materials and procedure

The materials and procedures used in Experiment 5 were identical to those used in Experiments 1–4 with the following exceptions: (1) Participants rated the pleasantness of each event on a 1 (very unpleasant) to 8 (very pleasant) scale, and (2) the anagram task always involved unscrambling a word that was unrelated to the judged event.

Results

The data of one participant were lost due to a computer error. The data of the remaining 93 participants were analyzed with a related-samples t-test comparing ratings on the revelation and control trials. This analysis showed no effect of revelation on pleasantness ratings, t (92) =.19, p =.85, SE = .04. Indeed, the mean ratings were nearly identical (M revelation = 4.07, SD revelation =.47, M control = 4.06, SD control = .41, Cohen’s dz = .02). These conclusions were confirmed by a Bayesian analysis, which produced a scaled JZS BF 01= 8.57, indicating that, given the data, the null hypothesis is 8.57 times more likely than the alternative hypothesis. The results of Experiment 5 converge with those of Experiments 3 and 4 as well as past work by Watkins and Peynircioğlu (1990) showing an absence of a revelation effect on non-episodic judgments.

Experiment 6

The results of Experiments 1 and 2 suggest that a revelation task has comparable effects on judgments about the personal past and personal future. The results of Experiments 3, 4, and 5 suggest that these effects do not occur when the same events are evaluated without reference to personal episodes. In Experiment 6, we attempted to determine whether the personal nature of the episodic experience was key to the revelation effects observed in Experiments 1 and 2. In order to do this, we asked that participants think of “a few of their closest friends” and estimate how many of these friends experienced an event in the past or would experience an event in the future. We decided to ask for judgments about a collection of friends to further explore the results of Experiments 3 and 4. Whereas in Experiments 3 and 4 participants judged how common the events were for people in general, in Experiment 6, the reference group consisted of people the participants knew personally. We thought that this might help to isolate the critical difference between the personal episodic judgments of Experiments 1 and 2 and the non-episodic judgments of Experiments 3 and 4. We thought that asking participants to make judgments about a group of friends might represent a middle ground between the personal and collective past and future. In Experiment 6, participants rated the same events that were used in Experiments 1–5.

A second rationale for Experiment 6 is that recent work has suggested that the same processes that are involved when we think of ourselves in the future are engaged when we adopt the perspective of another person (i.e., theory of mind). In fact, many of the same parallels that have been found between remembering and forecasting have been found with tasks that ask a person to adopt the perspective of another person (Buckner & Carroll, 2006; Jarvis & Miller, in press; Spreng, Mar, & Kim, 2009; Spreng & Grady, 2010). In Experiment 6, participants rated past and future life events adopting the perspective of a collection of their friends. Like Experiments 3 and 4, participants were asked how common each event was or would be, but instead of considering the population in general, they were asked how many of their close friends experienced/would experience the event in question. We intentionally left the reference point somewhat loose (“a few close friends”) to discourage an analytic strategy (e.g., Whittlesea & Price, 2001).

Method

Participants

One-hundred and twenty-eight undergraduate students at Binghamton University participated in exchange for partial credit toward a course requirement. Participants were tested individually.

Materials and procedure

The materials and procedures were identical to Experiment 5 with one major exception. Instead of rating each event according to how common it is in childhood or early adulthood, participants were asked to think of a few of their closest friends and rate how many had or would experience the event. For the past condition, participants were asked to think of how many of their friends experienced the event before the age of 13 years, and for the future condition participants rated how common the event would be for their friends during the ages of 24–34 years. They rated each event on an 8-point scale, with “1” meaning that the event happened to (or would happen to) none of their friends and an “8” meaning that the event happened to (or would happen to) all of their friends during the specified time period. The unrelated revelation task was used, and so before half of the life events, participants unscrambled an anagram to reveal a word that was not related to any of the words in the event. Given that the same patterns of results were found for the related and unrelated anagram experiments (Experiments 1–4), we used only unrelated anagrams in Experiment 6 to conserve resources.

Results

One participant’s data were lost due to a computer malfunction. The data of the remaining 127 participants were analyzed with a two (revelation condition: revealed vs. control) by two (judgment type: past vs. future) mixed factor analysis of variance on the ratings participants gave regarding the probability that their friends did or would experience the life events. Revelation condition was manipulated within-subjects and judgment type was manipulated between-subjects. The results are summarized in Table 3. There was a main effect of revelation condition. Events preceded by an anagram task received higher ratings than events in the control condition, F (1, 125) = 16.36, p <.001 MSE = .13, η2 p = .12. There was not a main effect for the type of judgment, F < 1 nor was there an interaction between revelation condition and judgment type, F (1, 125) = 1.48, p = .23 MSE = .13, η2 p = .01. A Bayesian t-test carried out on the ratings for revealed and control items, collapsed across past and future judgments, supported the conclusion of a revelation effect in this experiment. Given the data, the alternative hypothesis is much more likely than the null hypothesis, scaled JZS BF 10 = 174.02. Thus, the results mirror those of Experiments 1 and 2 with revelation effects observed for both past and future time frames. It seems that judgments based on imagined episodes in either the past or future are similarly susceptible to revelation effects, even when the episodes are imagined from another person’s perspective.

Between-experiment analyses

The findings so far suggest that the revelation effect occurs when participants rate events with respect to their own lives, regardless of whether these events may have taken place in the past or may take place in the future (Experiments 1 and 2) or are rated from the perspective of their close friends (Experiment 6). When the question is framed in terms of whether people in general are likely to experience the events, the revelation effect did not emerge (Experiments 3 and 4). To further explore the apparent differences across experiments, we conducted a series of cross-experiment comparisons focused on the differences between the episodic and non-episodic judgments. For simplicity, the event ratings were collapsed across the past and future conditions of each experiment. We then conducted two additional ANOVAs to determine if there was an interaction between revelation condition and experiment type. For each analysis, a two (revelation condition: revelation vs. control) by two (experiment type: autobiographical vs. nonautobiographical) mixed-factor ANOVA was conducted on the event ratings, with revelation condition as a within-subjects variable and experiment type as a between-subjects variable. For the analysis that included the data from Experiments 1 and 3, there was a main effect for revelation condition, F (1, 299) = 10.97, p =.001, MSE = .18, η2 p = .04 and a significant interaction between revelation condition and experiment type, F (1, 299) = 8.97, p <.003, MSE =.18, η2 p = .03. The results of the analysis of the data from Experiments 2 and 4 were very similar. Again, there was an overall effect of revelation condition, F (1, 216) = 13.33, p <.001, MSE = .14, η2 p = .06, and an interaction between revelation condition and experiment type, F (1, 216) = 9.21, p =.003, MSE = .14, η2 p = .04. There was no main effect for experiment type in either analysis (Fs < 1). Although cross-experiment comparisons should be interpreted cautiously, the significant interactions between revelation condition and experiment type support the conclusion that the revelation effect is larger for autobiographical memory judgments than non-autobiographical judgments about the same events.

Speculating on why revelation effects were found with validity judgments but not with other non-episodic judgments (Watkins & Peyrnircioglu, 1990), Bernstein et al. (2002) suggested that participants may have been more engaged in episodic memory tasks and validity judgments, compared with the non-episodic tasks used in past work on this topic (e.g., word frequency judgments, category typicality). We wondered if such an explanation could account for our results. To try to determine whether participants were less engaged in the non-episodic tasks, we first examined response times on the rating tasks. If participants took the non-episodic task less seriously, we might find faster median response times. We found no evidence for hypothesis. In fact, participants tended to respond more slowly on the non-episodic tasks than on the episodic tasks. When comparing average median response times in Experiment 1 (M = 2.86s, SD = 1.29s) with Experiment 3 (M = 3.24s, SD = 1.3s), participants were significantly slower on the non-episodic task used in Experiment 3, t (300) = 2.38, p =.018, SE = 1.56), d =.27. We also compared the average median response times in Experiments 2 and 4, and found slightly slower responses on the non-episodic task, but no statistically significant difference (Experiment 2: M=3.4s, SD =.96s vs. Experiment 4: M = 3.6s, SD =.94s), t (210) =1.49, p =.137, SE = 1.31,), d =.21).

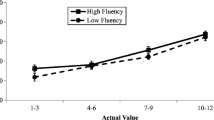

We further reasoned that if participants were similarly committed to the non-episodic task as the episodic tasks, we would see a convergence in the ratings for the various life events across tasks. Relatively common events, such as “found money in sofa cushions,” should be given higher ratings on both tasks, and uncommon events such as “found a valuable piece of jewelry,” should be given lower ratings on both tasks. On the other hand, if participants were committed to the episodic task but gave only perfunctory answers to the non-episodic task, we might expect a looser association between the two types of ratings. In fact, we found that the responses on the episodic and non-episodic tasks were strongly correlated for events taking place during childhood (r [58] =.91, p <.0001) and adulthood (r [58]=.92, p<.0001). In other words, events given low ratings when judged from an autobiographical perspective were also given low ratings when the question was about how common the events were in general.

In summary, the results of these supplementary analyses support the conclusion that the revelation effect is more likely to be observed when participants are instructed to base judgments on their own experience rather than make judgments about how common events are in general. Furthermore, we found no obvious support for the notion that participants approached the non-episodic task more carelessly than the episodic task.

General discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the revelation effect, a well-established phenomenon in episodic memory, would occur for judgments that involved different types of self-projection. The present results show that completing a simple cognitive task just prior to a judgment makes a person more likely to believe that a life event occurred in the past or would occur in the future. We also found that these effects are not limited to judgments about one’s own life. A revelation task made participants more likely to think that an event did occur or would occur in their friends’ lives.

The results also show similar boundary conditions for past and future judgments, as the revelation effect was limited to episodic judgments about the past and future. These findings mirror those of Watkins and Peynircioğlu (1990), and are also broadly consistent with work by Prull, Light, Collett, and Kennison (1998), who showed that older adults do not show revelation effects, even when tested under circumstances that induce robust revelation effects in younger adults. The current results dovetail with these findings when you consider the fact that age-related cognitive declines are much more pronounced for the episodic memory system than the semantic memory system (Addis, Wong, & Schacter, 2007; Head, Rodrigue, Kennedy, & Raz, 2008). That said, a subsequent study by Thapar and Sniezek (2008) showed comparable revelation effects for younger and older adults, suggesting that the presence and magnitude of the revelation effect across the lifespan has not been clearly established.

As noted in the introduction to Experiment 5, the conclusion that revelation judgments are limited to episodic judgments has been called into question by the results of Bernstein et al. (2002), which showed a revelation effect on true/false judgments to general knowledge statements, and the results of Kronlund and Bernstein (2006), which showed that brand preference increased after a revelation task. Experiment 5 was an attempt to reconcile the inconsistent effects of revelation on non-episodic judgments. We wondered if questions that related to the positivity of the event would be more likely to be affected by revelation, as the two studies that did report such effects assessed judgments of truthfulness and preference. However, we found no evidence of a revelation effect on pleasantness ratings for the life events.

We considered the possibility that lower levels of task engagement may be responsible for the differences between the episodic and non-episodic tasks, as suggested by Bernstein et al. (2002). Our post-hoc analyses found no evidence that participants were more careless in their responses on the non-episodic task in terms of response times. In addition, we found a strong correlation between the ratings given to the events across the episodic and non-episodic tasks. Although not a definitive index of effort, the strong correlations between ratings suggest that participants took the task seriously enough to arrive at very similar ratings to the participants who made judgments about their own lives. In sum, our supplementary analyses do not support the idea that participants were less engaged in the non-episodic tasks compared with the episodic tasks. We have no alternative speculative account of the mixed results across studies. However, we note that our results align well with the results of Watkins and Peynircioğlu (1990). In addition, the large N in our studies, the multiple replications of null results, our use of the same stimuli in the episodic and non-episodic tasks, and the very modest shifts in the instructions given to participants across episodic and non-episodic tasks bolster our confidence in our conclusion that episodic tasks appear less susceptible to the revelation effect compared with non-episodic tasks.

It is intriguing that both past and future judgments showed revelation effects in Experiments 1 and 2 when the events were evaluated as personal episodes, whereas the effects were diminished when the same events were subject to non-episodic judgments. This pattern of results is especially interesting when considered in light of the results of Experiment 6, in which participants were asked to consider how common the events were and would be among their friends. We chose this wording in part because of research showing the commonalities between remembering the past, imagining the future, and perspective taking (theory of mind) (Buckner & Carroll, 2007; Mullally & Maguire, 2014), and in part because we wanted to conduct an experiment that seemed to include aspects of both the collective judgments required in Experiments 3 and 4 and the personal judgments required in Experiments 1 and 2. The judgments in Experiment 6 asked participants to consider multiple people, but people who were known by the participant. A revelation effect was found in this case, which rules out the possibility that the absence of the effect in Experiments 3 and 4 was because the question asked for a judgment based on multiple people. Rather, the findings suggest that participants approached this task similarly to the episodic past and future tasks. These results seem consistent with current thinking about the link between remembering, imagining future events, and perspective taking, which emphasizes the common role of scene construction (Hassabis & Maguire, 2007). It may be that asking participants about their own circle of friends encourages them to try to imagine scenarios in which these events did or would play out, with images of their friends serving as familiar scaffolding that may facilitate generating and maintaining such scenes. Participants may have imagined their friends taking part in the various events, similar to the way they may have tried to reconstruct and construct the events when they were making the judgments on their own behalf.

The current pattern of results also provides support for models that conceptualize episodic memory as a component of a larger self- projection system (Addis, Wong & Schacter, 2008; Buckner & Carroll, 2007; Mullally & Maguire, 2014). One relatively unexplored prediction made by these types of models is that processes like prospection, navigation, and theory of mind that share a common cognitive architecture with the episodic memory system may be prone to some of the same kinds of illusions and biases that have been demonstrated over many years of research examining episodic memory. The current results are some of the first demonstrating that well-known memory illusions like the revelation effect can be shown to act similarly on future-based judgments or on judgments regarding mental simulations of the conscious experiences of others. Future research might want to expand upon this work by seeing if other episodic memory illusions can be observed for future based judgments. For example, visualization-based illusions like the imagination inflation effect (Garry, Manning, Loftus, & Sherman, 1996) may also translate well from judgments about the past to judgments about the future, given the critical role of mental simulation in both remembering the past and imagining the future.

The revelation effect is a puzzling phenomenon, which has remained largely resistant to a clear theoretical explanation. In their recent meta-analysis, Aßfalg, Bernstein, and Hockley (2017) concluded that none of the accounts that have been proposed over the years are capable of explaining the extant data to an adequate degree of specificity. Unfortunately, the current data are not able to break this theoretical impasse. The results could be reconciled with accounts that assume that revelation increases the perceived familiarity of events that follow the task (e.g., Bernstein et al., 2002; Westerman & Greene, 1998). Likewise, the data are consistent with a criterion-flux account (e.g., Hicks & Marsh, 1998; Hockley & Niewiadomski, 2001), which assumes that the response criterion is lowered after a revelation task. That said, the present data seem at odds with one particular version of a familiarity increase account. A fluency account of the revelation effect assumes that the ease of reading the test item after having just completed the comparatively more difficult revelation task creates a perception of processing fluency, which is then translated into a sense of familiarity (e.g. Bernstein et al., 2002). Fluency-based memory illusions are well documented (e.g., Jacoby & Whitehouse, 1989; Westerman, Lanksa, & Olds, 2015; Whittlesea, 1993), and this account fits well within a large body of work suggesting the important role of fluency in memory decision making. However, fluency effects are also very general, and are not limited to episodic memory judgments. Indeed, judgments of category typicality (Oppenheimer & Frank, 2007) and affective preference (Reber, Winkielman, & Schwarz, 1998; Westerman et al., 2015) have been found to be influenced by enhanced levels of relative fluency. If the revelation effect is based on higher processing fluency, then one might expect to see the effect in when the events were rated for pleasantness (Experiment 5) or commonality (Experiments 3 and 4). The fact that the revelation effect was limited to episodic memory judgments would seem to provide some evidence against this particular account.

In summary, the present results show that judgments about the past, judgments about the future, and judgments made from the perspective of other people are similarly affected by a revelation task completed just prior to the judgments. Although the mechanism responsible for the revelation effect remains to be specified, it appears that past and future thinking are subject to similar decision-making biases and that a simple cognitive task just prior to a self-projection-related decision leads people to believe that events did or will occur. The results also affirm the idea that the revelation effect is limited to episodic judgments (Watkins & Peynircioğlu, 1990) and show that this is a common boundary condition for past and future episodes.

References

Addis, D. R., Sacchetti, D. C., Ally, B. A., Budson, A. E., & Schacter, D. L. (2009). Episodic simulation of future events is impaired in mild Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychologia, 47, 2660–2671. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.05.018

Addis, D. R., Wong, A. T., & Schacter, D. L. (2007). Remembering the past and imagining the future: Common and distinct neural substrates during event construction and elaboration. Neuropsychologia, 45, 1363–1377. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.10.016

Aßfalg, A. (2017). The revelation effect. In R. Pohl (Ed.), Cognitive illusions: Intriguing phenomena in judgement, thinking and memory (2nd ed., pp. 339–355). New York: Routledge.

Aßfalg, A., & Bernstein, D. M. (2012). Puzzles produce strangers: A puzzling result for revelation effect theories. Journal of Memory and Language, 67, 86–92. doi:10.1016/j.jml.2011.12.011

Aßfalg, A., Bernstein, D. M., & Hockley, W. (2017). The revelation effect: A meta-analytic test of hypotheses. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. doi:10.3758/s13423-017-1227-6. Advance online publication.

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bernstein, D. M., Godfrey, R. D., & Davison, A. (2004). Conditions affecting the revelation effect for autobiographical memory. Memory & Cognition, 32, 455–462. doi:10.3758/BF03195838

Bernstein, D. M., Whittlesea, B. W. A., & Loftus, E. F. (2002). Increasing confidence in remote autobiographical memory and general knowledge: Extensions of the revelation effect. Memory & Cognition, 30, 432–438. doi:10.3758/BF03194943

Berntsen, D., & Bohn, A. (2010). Remembering and forecasting: The relation between autobiographical memory and episodic future thinking. Memory & Cognition, 38, 265–278. doi:10.3758/MC.38.3.265

Bornstein, B. H., & Neely, C. B. (2001). The revelation effect in frequency judgment. Memory & Cognition, 29, 209–213. doi:10.3758/BF03194914

Bornstein, B. H., & Wilson, J. R. (2004). Extending the revelation effect to faces: Haven't we met before? Memory, 12, 140–146. doi:10.1080/09658210244000289

Brainerd, C. J., & Reyna, V. F. (2005). The science of false memory. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195154054.001.0001

Buckner, R. L., & Carroll, D. C. (2007). Self-projection and the brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 49–57. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.004

Cameron, T. E., & Hockley, W. E. (2000). The revelation effect for item and associative recognition: Familiarity versus recollection. Memory & Cognition, 28, 176–183.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

D'Argembeau, A., & Van Der Linden, M. (2004). Phenomenal characteristics associated with projecting oneself back into the past and forward into the future: Influence of valence and temporal distance. Consciousness and Cognition, 13, 844–858. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2004.07.007

D'Argembeau, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2006). Individual differences in the phenomenology of mental time travel: The effect of vivid visual imagery and emotion regulation strategies. Consciousness and Cognition, 15, 342–350. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2005.09.001

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. doi:10.3758/BF03193146

Fields, L. M., & Brown, A. S. (2015). Occurrence, plausibility, and desirability for 124 Life Events Inventory Items. Behavior Research Methods, 47, 529–537. doi:10.3758/s13428-014-0484-9

Garry, M., Manning, C. G., Loftus, E. L., & Sherman, S. J. (1996). Imagination inflation: Imagining a childhood event inflates confidence that it occurred. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 3, 208–214.

Guttentag, R., & Dunn, J. (2003). Judgments of remembering: The revelation effect in children and adults. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 86, 153–167. doi:10.1016/S0022-0965(03)00135-8

Hassabis, D., Kumaran, D., Vann, S. D., & Maguire, E. A. (2007). Patients with hippocampal amnesia cannot imagine new experiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104, 1726–1731. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0610561104

Hassabis, D., & Maguire, E. A. (2007). Deconstructing episodic memory with construction. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 299–306. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2007.05.001

Head, D., Rodrigue, K. M., Kennedy, K. M., & Raz, N. (2008). Neuroanatomical and cognitive mediators of age-related differences in episodic memory. Neuropsychology, 22, 491–507. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.22.4.491

Hicks, J. L., & Marsh, R. L. (1998). A decrement-to-familiarity interpretation of the revelation effect from forced-choice tests of recognition memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 24, 1105–1120. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.24.5.1105

Hockley, W. E., & Niewiadomski, M. W. (2001). Interrupting recognition memory: Tests of a criterion-change account of the revelation effect. Memory & Cognition, 29, 1176–1184. doi:10.3758/BF03206387

Jacoby, L. L., & Whitehouse, K. (1989). An illusion of memory: False recognition influenced by unconscious perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 118, 126–135. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.118.2.126

Jarvis, S.N. & Miller J.K. (in press). Self-projection in younger and older adults: A study of episodic memory, prospection, and theory of mind. Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition. doi:10.1080/13825585.2016.1219314

Klein, S. B., Loftus, J., & Kihlstrom, J. F. (2002). Memory and temporal experience: The effects of episodic memory loss on an amnesic patient's ability to remember the past and imagine the future. Social Cognition, 20, 353–379. doi:10.1521/soco.20.5.353.21125

Kleinfield, N. R. (2016, April 30). Fraying at the edges. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com

Kronlund, A., & Bernstein, D. M. (2006). Unscrambling words increases brand name recognition and preference. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 681–687. doi:10.1002/acp.1220

LeCompte, D. C. (1995). Recollective experience in the revelation effect: Separating the contributions of recollection and familiarity. Memory & Cognition, 23, 324–334. doi:10.3758/BF03197234

Leynes, P. A., Landau, J., Walker, J., & Addante, R. J. (2004). Event-related potential evidence for multiple causes of the revelation effect. Consciousness and Cognition, 14, 327–350. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2004.08.005

Loftus, E. F. (1992). When a lie becomes memory's truth: Memory distortion after exposure to misinformation. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 145–147. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.ep10769035

Loftus, E. F., & Pickrell, J. E. (1995). The formation of false memories. Psychiatric Annals, 25, 720–725. doi:10.3928/0048-5713-19951201-07

Luo, C. R. (1993). Enhanced feeling of recognition: Effects of identifying and manipulating test items on recognition memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 19, 405–413. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.19.2.405

Mullally, S. L., & Maguire, E. A. (2014). Memory, imagination, and predicting the future: A common brain mechanism? The Neuroscientist, 10, 1–15. doi:10.1177/1073858413495091

Mulligan, N. W. (2007). The revelation effect: Moderating influences of encoding conditions and type of recognition test. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14, 866–870.

Neisser, U., & Harsch, N. (1992). Phantom flashbulbs: False recollections of hearing news about challenger. In E. Winograd & U. Neisser (Eds.), Affect and accuracy in recall: Studies of "Flashbulb" memories. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511664069.003

Niewiadomski, M. W., & Hockley, W. E. (2001). Interrupting recognition memory: Tests of familiarity-based accounts of the revelation effect. Memory & Cognition, 29, 1130–1138. doi:10.3758/BF03206382

Okuda, J., Fujii, T., Ohtake, H., Tsukiura, T., Tanji, K., Suzuki, K., … Yamadori, A. (2003). Thinking of the future and past: The roles of the frontal pole and the medial temporal lobes. Neuroimage, 19, 1369–1380. doi:10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00179-4

Oppenheimer, D. M., & Frank, M. F. (2007). A rose in any other font would not smell as sweet: Effects of perceptual fluency on categorization. Cognition, 106, 1178–1194.

Payne, D. G. (1987). Hypermnesia and reminiscence in recall: A historical and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 10, 5–27. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.101.1.5

Peynircioğlu, Z. F., & Tekcan, A. İ. (1993). Revelation effect: Effort or priming does not create the sense of familiarity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 19, 382–388. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.19.2.382

Prull, M. W., Light, L., Collett, M. E., & Kennison, R. F. (1998). Age-related differences in memory illusions: Revelation effect. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 5, 147–165. doi:10.1076/anec.5.2.147.598

Reber, R., Winkielman, P., & Schwarz, N. (1998). Effects of perceptual fluency on affective judgments. Psychological Science, 9, 45–48. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00008

Rouder, J. N., Speckman, P. L., Sun, D., & Morey, K. D. (2009). Bayesian t tests for accepting and rejecting the null hypothesis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 225–237. doi:10.3758/PBR.16.2.225

Schacter, D. L. (2012). Adaptive constructive processes and the future of memory. The American Psychologist, 67. doi:10.1037/a0029869

Schacter, D. L., & Addis, D. R. (2007). The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory: Remembering the past and imagining the future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences, 362(March), 773–786. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2087

Schacter, D. L., Addis, D. R., Hassabis, D., Martin, V. C., Spreng, R. N., & Szpunar, K. K. (2012). The future of memory: Remembering, imagining, and the brain. Neuron, 76. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.001

Schacter, D. L., Addis, D. R., & Buckner, R. L. (2007). Remembering the past to imagine the future: The prospective brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8, 657–661. doi:10.1038/nrn2213

Schacter, D. L., Gaesser, B., & Addis, D. R. (2013). Remembering the past and imagining the future in the elderly. Gerontology, 59, 143–151. doi:10.1159/000342198

Spreng, R. N., & Grady, C. L. (2010). Patterns of brain activity supporting autobiographical memory, prospection, and theory of mind, and their relationship to the default mode network. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22, 1112–1123. doi:10.1162/jocn.2009.21282

Spreng, R. N., & Levine, B. (2006). The temporal distribution of past and future autobiographical events across the lifespan. Memory & Cognition, 34, 1644–1651. doi:10.3758/BF03195927

Spreng, R. N., Mar, R. A., & Kim, A. S. (2009). The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: A quantitative meta-analysis. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 21, 489–510. doi:10.1162/jocn.2008.21029

Szpunar, K. K., Watson, J. M., & McDermott, K. B. (2007). Neural substrates of envisioning the future. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104, 642–647. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0610082104

Thapar, A., & Sniezek, A. M. (2008). Aging and the revelation effect. Psychology and Aging, 23, 473–477. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.473

Verde, M. F., & Rotello, C. M. (2004). ROC curves show that the revelation effect is not a single phenomenon. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 11, 560–566. doi:10.3758/BF03196611

Watkins, M. J., & Peynircioğlu, Z. F. (1990). The revelation effect: When disguising test items induces recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 16, 1012–1020. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.16.6.1012

Westerman, D. L. (2000). Recollection-based recognition eliminates the revelation effect in memory. Memory & Cognition, 28, 167–175.

Westerman, D. L., & Greene, R. L. (1996). On the generality of the revelation effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 22, 1147–1153. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.22.5.1147

Westerman, D. L., & Greene, R. L. (1998). The revelation that the revelation effect is not due to revelation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 24, 377–386. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.24.2.377

Westerman, D. L., Lanksa, M., & Olds, J. M. (2015). The effect of processing fluency on impressions of familiarity and liking. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 41, 426–438. doi:10.1037/a0038356

Whittlesea, B. W. A. (1993). Illusions of familiarity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 19, 1235–1253. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.19.6.1235

Whittlesea, B. W. A., & Price, J. R. (2001). Implicit/explicit memory versus analytic/nonanalytic processing: Rethinking the mere exposure effect. Memory & Cognition, 29, 234–246. doi:10.3758/BF03194917

Whittlesea, B. W. A., & Williams, L. D. (2001). The discrepancy-attribution hypothesis II: Expectation, uncertainty, surprise, and feelings of familiarity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 27, 14–33. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.27.1.14

Williams, J. M. G., Ellis, N. C., Tyers, C., Healy, H., Rose, G., & MacLeod, A. K. (1996). The specificity of autobiographical memory and imageability of the future. Memory & Cognition, 24, 116–125. doi:10.3758/BF03197278

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9.2(pt. 2), 1–27. doi:10.1037/h0025848

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Westerman, D.L., Miller, J.K. & Lloyd, M.E. Revelation effects in remembering, forecasting, and perspective taking. Mem Cogn 45, 1002–1013 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-017-0710-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-017-0710-7