Abstract

Previous research indicates that alcohol intoxication impairs inhibitory control and that the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (rDLPFC) is a functional brain region important for exercising control over thoughts and behaviour. At the same time, the extent to which changes in inhibitory control following initial intoxication mediate subsequent drinking behaviours has not been elucidated fully. Ascertaining the extent to which inhibitory control impairments drive alcohol consumption, we applied continuous theta burst transcranial magnetic stimulation (rDLPFC cTBS vs. control) to isolate how inhibitory control impairments (measured using the Stop-Signal task) shape ad libitum alcohol consumption in a pseudo taste test. Twenty participants (13 males) took part in a within-participants design; their age ranged between 18 and 27 years (M = 20.95, SD = 2.74). Results indicate that following rDLPFC cTBS participants’ inhibitory control was impaired, and ad libitum consumption increased. The relationship between stimulation and consumption did not appear to be mediated by inhibitory control in the present study. Overall, findings suggest that applying TMS to the rDLPFC may inhibit neural activity and increase alcohol consumption. Future research with greater power is recommended to determine the extent to which inhibitory control is the primary mechanism by which the rDLPFC exerts influence over alcohol consumption, and the degree to which other cognitive processes may play a role.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When talking about alcohol-related behaviours, “just going for one!” is a commonly expressed sentiment that all too frequently appears to precede heavy (albeit unplanned) alcohol consumption. According to such anecdotal wisdom, the consumption of alcohol may lessen self-control and undermine good intentions of engaging in restrained drinking. The (in)ability to control or suppress preponent responses, known as inhibitory control (de Wit & Richards, 2004; De Wit, 2009; Olmstead, 2006), is increasingly being recognized in the literature as both a determinant and a consequence of alcohol consumption (De Wit 2009), as well as being implicated in other behaviours that require exerting a degree of self-control (Houben, Nederkoorn, & Jansen, 2014; Lane, Cherek, Pietras, & Tcheremissine, 2004). Inhibitory control impairments have been documented in samples of alcohol-dependent individuals (Goudriaan, Oosterlaan, De Beurs, & Van Den Brink, 2006; Lawrence, Luty, Bogdan, Sahakian, & Clark, 2009), and longitudinal studies suggest that inhibitory control predicts both future alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems (Nigg et al., 2006). Concurrently, lower levels of inhibitory control appear to be associated with heavy, hazardous and problematic drinking in nondependent samples (Christiansen, Cole, Goudie, & Field, 2012; Murphy & Garavan, 2011; Nederkoorn, Baltus, Guerrieri, & Wiers, 2009). As such, current evidence converges to implicate inhibitory control in the regulation of alcohol consumption.

Alcohol preloads (acute intoxication) have been found to result in subsequent increases in consumption (Rose & Grunsell, 2008) and to be associated with transient impairments in inhibitory control (Caswell, Morgan, & Duka, 2013; Fillmore & Rush, 2001; Rose & Duka, 2006; Weafer & Fillmore, 2012). Fluctuations in inhibitory control have been proposed to mediate the relationship between the alcohol preload and subsequent alcohol consumption (Field, Wiers, Christiansen, Fillmore, & Verster, 2010; Jones, Christiansen, Nederkoorn, Houben, & Field, 2013). Empirical evidence of the extent to which inhibitory control mediates the association between initial intoxication and continued alcohol consumption, however, is mixed. Some studies find that impairments in inhibitory control correlate with subsequent consumption (Weafer & Fillmore, 2008), while others investigating this directly find no mediation (Christiansen, Rose, Cole, & Field, 2013). A particular research challenge is to unpack the reasons why initial alcohol consumption may inadvertently lead to continued drinking (e.g., via impulsivity or craving; Rose & Grunsell 2008). Existing paradigms frequently administer alcohol to induce impaired inhibitory control and to examine how this impacts control over subsequent alcohol consumption. However, acute alcohol intoxication is also associated with a range of changes to other cognitive and psychological processes (e.g., attentional bias and motivations to drink; Fadardi & Cox (2008)), and it has therefore been difficult to disentangle the extent to which inhibitory control is implicated in the maintenance of alcohol consumption. Also in view of wide-reaching costs associated with excessive alcohol consumption (World Health Organization, 2014), more research is therefore required to examine this relationship, and to ascertain underlying neuropharmacological processes (Volkow, Koob, & McLellan, 2016).

Anticipation of reward has been associated with heightened activations in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), the medial orbital frontal cortex and activation in the ventral striatum (VS) in individuals with substance use disorders (Luijten, Schellekens, Kuehn, Machielse, & Sescousse, 2017 for a recent review). In response to alcohol consumption, fMRI studies point to acute decreases in the activation of neural regions associated with inhibitory control, including the DLPFC (Bjork & Gilman, 2014). Meanwhile, Positron Emission Tomography (PET) research on healthy participants suggests that moderate doses of alcohol are associated with reductions in overall brain metabolism, although metabolic increases are observed in mesolimbic regions involved in the incentive-motivational system, including the VS and nucleus accumbens (NAc) (Volkow et al., 2008). Thus, by examining the acute responses of the brain to alcohol, researchers have begun to illuminate the effects and drivers of alcohol intoxication, behavior, and cognition (Bjork & Gilman 2014; Volkow et al., 2008). However, methods, such as fMRI and PET, do not allow us to investigate how alcohol-related neurological changes directly influence cognitive processes and how these may, in turn, drive fluctuations in alcohol consumption.

Addressing this by enabling researchers to assess the causal links between specific regions and their functions, Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) is a useful means of impeding particular brain areas. Existing research implicates regions of the prefrontal cortex, including the rDLPFC, in inhibitory control processes, and a recent review documents that active TMS stimulation (compared with control) to prefrontal regions is an effective means of impairing inhibitory control (Lowe, Manocchio, Safati & Hall, 2018). While this evidence implicates rDLPFC in the inhibitory control processing, the extent to which this impacts alcohol consumption has yet to be elucidated fully.

The present study used TMS to impede rDLPFC functioning to ascertain the extent to which inhibition impairments contribute to alcohol consumption. Specifically, in view of the preponderance of research impairing inhibitory control by acute administration alcohol (Caswell et al., 2013; Fillmore & Rush 2001; Rose & Duka 2006; Weafer & Fillmore 2012), we used TMS to assess directly the relationship between impaired inhibitory control and alcohol consumption, independent from the wider pharmacological effects of alcohol. A within-participant design was utilized to the test the hypothesis that TMS-induced impaired inhibitory control would result in increased alcohol consumption ad libitum compared with control stimulation and that impaired inhibitory control would mediate this relationship.

Method

Participants

Twenty participants (13 males, age between 18 and 27 years,M = 20.95, SD = 2.74) were recruited in response to online advertisements which sought to recruit fluent English speakers aged between 18 and 49 years who regularly use alcohol and exceed recommended weekly drinking guidelines (14 units). Due to the risks associated with TMS, participants also were required to complete a medical screening form. Participants whose medical history indicated any neurological risk factors, syncopy, drugs active in the central nervous system (e.g., antipsychotics, antidepressants, or recreational stimulants), and poor levels of sleep were excluded from the study (Rossi, Hallett, Rossini, & Pascual-Leone, 2009; Wassermann, 1998). It is worth noting that the risks associated with cTBS are minimal, with only one known case of seizure as of Rossi et al. (2009). Participants who had sought help concerning their drinking or had a history of alcohol dependency also were excluded. As reimbursement for their time, participants were either awarded course credit or £12. The study received ethical review and clearance from the University’s Department of Psychology Research Ethics Committee.

Design

A counterbalanced, within-participants design was implemented. The independent variable of TMS stimulation consisted of two levels: cTBS TMS stimulation to the rDLPFC, and control stimulation consisting of cTBS at the same intensity to the Vertex. Measures of inhibitory control and subsequent drinking were taken. Approximately 6 minutes passed between cTBS and the subsequent drinking task. This is the approximate time to complete the inhibitory control task.

Materials

Questionnaires

Time Line Follow Back (TLFB: Sobell & Sobell, 1990)

Participants are required to retrospectively report their daily alcohol consumption (in units) for the previous 14 days.

Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT: Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente & Grant, 1993)

The AUDIT is a 10-item questionnaire concerning levels of alcohol consumption and its consequences. Scores range from 0-40, with scores ≥8 representative of alcohol consumption of a hazardous level.

Barrett Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11: Patton, Stanford, & Barratt, 1995)

The BIS is a multidimensional scale, consisting of three subscales; attentional, motor and nonplanning impulsiveness. BIS-11 includes 30 fixed response items (e.g., I plan tasks carefully), which are assessed on a 4-point scale (rarely/never – almost always/always). Higher scores are indicative of increased impulsivity.

Behavioural tasks

Stop-signal task (SST: Verbruggen, Logan, & Stevens, 2008)

The Stop Signal task consists of two concurrent tasks: a go task (75% of trials), which is a choice reaction task where participants categorise arrows on the screen based on their orientation (left or right), and a stop task (25% of trials) where an auditory tone (the stop signal) indicates that participants should inhibit their response to the go signal. Participants are required to respond as quickly and accurately as possible to the stimuli with a predetermined corresponding key. Upon hearing the auditory tone (the stop signal) participants are required to inhibit their response. After 2,000 ms, the trial will time out.

On the stop trials, tones are delivered at fixed delays (known as Stop-signal delays or SSD) of between 50 ms and 500 ms following the presentation of the go stimulus. The stop signal task uses these SSDs dynamically, based on participant performance. The one-up one-down tracking procedure (Logan, Schachar, & Tannock, 1997) was implemented, which adjusts the SSDs after each trial. After successful inhibition trials, the SSD increases by 50 ms, handicapping the stop signal process on the next stop signal trial. Unsuccessful inhibition trials result in the SSD decreasing by 50 ms. In accordance with the “horse race” model, the degree of difficulty in inhibiting responding increases as the delay between the go stimulus and the stop signal increases (Logan, Cowan, & Davis, 1984). Providing an outcome variable of stop-signal reaction time (SSRT). The SST was delivered using Millisecond Inquisit Lab version 4. Participants received 3 experimental blocks of 64 trials, allowing for a short break between each block, taking approximately 6 minutes to complete.

Theta Burst stimulation procedure

Continuous theta burst stimulation (cTBS) was performed using a 70-mm figure-of-eight stimulation coil (Magstim D702 Coil), connected to a Magstim SuperRapid 2 Stimulator (The Magstim Company, Carmarthenshire, Wales). This produces a magnetic field of up to 0.8 T at the coil surface. To appropriately select the TMS stimulation intensity for each participant, the resting motor threshold (rMT) for the first dorsal interosseous muscle (FDI) of the participant’s dominant hand was visually determined (Pridmore, Fernandes, Nahas, Liberatos, & George, 1998). The coil was positioned over the left or right motor cortex (for right or left-hand dominance respectively) in correspondence with the optimal scalp position (OSP). It was detected by moving the intersection of the coil in 1-cm steps around the motor hand area of the left motor cortex, while delivering TMS pulses at constant intensity. The rMT was defined as the lowest stimulus intensity able to evoke a visible finger twitch on at least five of ten trials.

cTBS was delivered over the rDLPFC. The vertex was chosen as a control site to account for non-specific effects of TMS. The approximate locations of the stimulating areas were identified on each participant's scalp by means of the 10-20 EEG System Positioning. In keeping with past research, for rDLPFC stimulation, the coil was positioned on the F4 location. Three-pulse bursts at 50 Hz repeated every 200 ms for 40s were delivered at 80% of the subject’s resting MT (equivalent to “continuous theta burst stimulation” cTBS), resulting in 600 pulses in total (Huang, Edwards, Rounis, Bhatia, & Rothwell, 2005). The coil was positioned tangentially to the scalp, at 90° from the midsagittal line, to modulate contralateral M1 excitability and interfere with cognitive functions. The coil was held by hand throughout stimulation and the exact coil position was marked by ink to ensure an accurate and consistent positioning of the coil throughout the experiment. The inhibitory effect of cTBS with this protocol lasts up to 30 minutes (Cho et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2005).

Ad libitum alcohol consumption

Ad libitum alcohol consumption was measured by means of the Bogus Taste test. Participants were presented with three different beers (330 ml each) and asked to rate them on several dimensions of taste (e.g., bitterness and sweetness). They were informed that they could consume as much or little as they liked to complete the task successfully. Ad libitum consumption is measured by subtracting the remaining volume from the initial volume.

Procedure

Participants who expressed an interest in participation were first required to complete a medical screening questionnaire to ensure they could undergo TMS, additionally affording them the opportunity to ask the researcher questions. Upon entering the laboratory, participants were required to provide informed consent and supply a Breath Alcohol Concentration (BrAC) of 0.0 mg (Lion Alcolmeter 400, Lion Laboratories, Vale of Glamorgan, United Kingdom). During the first session, participants completed a battery of questionnaires, including demographic information, the TLFB, AUDIT, and BIS-11. Participants completed the SST prior to TMS stimulation in the first session to provide a baseline measure of SSRT. The within-participant order of conditions was counterbalanced. Participants either received cTBS or control stimulation in the first session and in the second session, which took place at least 1 week later, participants completed the opposite TMS condition. In both cases, participants completed the SST post stimulation, followed immediately by the bogus taste task.

Data Reduction and Statistical Analysis

Before calculating SSRT, trails where the reaction times were less than 100 ms and greater than 2,000 ms, and those greater than three standard deviations above the participants mean were removed. SSRT was then calculated by extracting the percentage errors (failure to inhibit response on stop trials) at each of the SSDs (50-500 ms, at 50-ms intervals), then calculating an SSRT value for each SSDs based on the reaction time (RT) distribution. Overall SSRT score was calculated by averaging the SSRT values for each of the SSDs. Impaired response inhibition is demonstrated through longer SSRT values; SSRT represents an estimate of the time required to stop initiated Go response (Band, van der Molen, & Logan, 2003). Repeated measures ANOVAs were used to analyze differences between baseline and conditions for both SSRT and GoRT and for ad libitum consumption following rDLPFC and control cTBS. Within-participants mediation analysis to assess the relationship between impairments in inhibitory control and ad libitum consumption was implements as per Montoya and Hayes (2017), using the MEMORE macro for SPSS developed by the same authors.

Results

With regard sample characteristics, participants age and alcohol involvement descriptive statistics are comparable with previous studies investigating the effects of acute alcohol on inhibitory control (Christiansen et al., 2013; Rose & Grunsell, 2008) (Table 1). Table 1 also contains descriptive statistics for the TMS protocol, including the output required to stimulate the motor cortex (rMT) and the cTBS TMS intensity output.

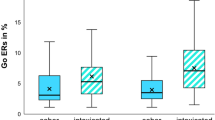

A repeated-measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to investigate the effects of stimulation on inhibitory control as measured by stop-signal reaction time (SSRT). A main effect of stimulation was found (F(2, 36) = 16.70, p < .001, η\( \frac{2}{p} \) = 0.47). Planned comparisons revealed that while there was a significant increase in SSRT found postactive stimulation (M = 249.97, SD = 31.40; F(1, 18) = 18.58, p < 0.001, η\( \frac{2}{p} \) = 0.51), there was no significant difference between baseline SSRT (M = 217.83, SD = 19.41) and postcontrol stimulation (M = 217.64, SD = 15.48; F(1, 18) = 0.003, p = .96, η\( \frac{2}{p} \) = 0.00). This suggests the active TBS to the rDLPFC resulted in significant impairments to inhibitory control (Figure 1). A further repeated-measures ANOVA was undertaken to assess if stimulation resulted in changes in go reaction times (RT), revealing no significant differences (F(2, 34) = 0.41, p = .67, η\( \frac{2}{p} \) = 0.02; Figure 2).

A final repeated-measures ANOVA was used to determine whether there was an effect of cTBS stimulation on ad libitum alcohol consumption. Results showed that participants consumed significantly more beer following active stimulation (M = 525.70, SD = 313.29) compared with postcontrol stimulation (M = 293.40, SD = 289.56; F(1, 19) = 19.22, p < 0.001, η\( \frac{2}{p} \) = 0.50; Figure 3).

A within-participants mediation analysis was undertaken using the MEMORE macro for IBM SPSS (Montoya & Hayes, 2017) to test whether impairments in inhibitory control mediate changes in ad libitum alcohol consumption (Figure 4). Overall, the analysis showed no significant mediated pathway. The analysis revealed a significant direct effect (c) of cTBS on ad libitum beer consumption (c1 = 232.30, t(19) = 4.38, p < 0.001, 95% CI [121.38, 343.22]). A significant pathway a was also found (a1 = −31.43, t(19) = −4.38, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−46.45, −16.42]), confirming the effect of stimulation on inhibitory control. However, the b pathway was insignificant (b1 = 2.08, t(19) = 0.95, p = 0.36, 95% CI [−2.57, 6.75]). Furthermore, a significant indirect pathway (c’) was found (c’ = 297.96, t(19) = 3.38, p < 0.01, 95% CI [112.13, 483.79]). However, because the b pathway in the current model was insignificant, the indication of the current findings is that impairments to inhibitory control do not mediate subsequent ad libitum consumption. Post-hoc Monte Carlo Simulation power analysis, running 1,000 simulations, revealed that to achieve a power of 0.80 an N of 200 is required.

Discussion

Using TMS to impede the functioning of the prefrontal cortex, the current study tested the hypothesis that inhibitory control impairments mediate the relationship between cTBS to the rDLPFC and alcohol consumption. Results indicate that active (relative to control) stimulation impaired inhibitory control and increased alcohol consumption. This suggests that the rDLPFC is important in the regulation and maintenance of alcohol consumption. However, contrary to previous suggestions (Field et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2013), the current study did not yield support for the notion that impairments in inhibitory control mediate the relationship between initial and continued alcohol consumption. Our findings therefore indicate that while the rDLPFC appears to be implicated in the maintenance of alcohol consumption and impaired inhibitory control, other executive functions and psychological processes may also play a role in elevated alcohol consumption following initial intoxication.

A strength of the current study was that we were able to instigate behavioral change in terms of actual alcohol consumption by transiently impairing the rDLPFC using TMS. Previous research investigating the extent to which alcohol undermines people’s ability to exert control over behaviors has tended to rely on administering alcohol to individuals as the means of impeding behavioral control (Caswell et al., 2013; Fillmore & Rush 2001; Rose & Duka 2006; Weafer and Fillmore 2012). This work has been important in documenting the effects of acute intoxication on attentional bias (Weafer & Fillmore, 2013), executive functioning (Christiansen et al., 2013) and risk-taking (Lane et al., 2004). However, in view of findings indicating that acute alcohol exposure impacts wider executive and psychological functions (Field et al., 2010), to date it has been difficult to disentangle the relative contribution of inhibitory control to the continuation of alcohol consumption following initial intoxication. By using TMS to isolate inhibitory control impairments at the neurological level from pharmacological effects of alcohol, our study implicates temporally induced changes to the rDLPFC and inhibitory control in heightened alcohol consumption.

Our findings suggest that there was an association between stimulation of rDLPFC and impaired control and alcohol consumption, respectively. This provides support for research implicating the DLPFC in alcohol consumption (Volkow et al., 2008) as well as appetitive behaviours (Jansen et al., 2013; Lowe, Vincent, & Hall, 2017) more generally. Using, PET, Volkow et al. (2008), for example, found reduced activity in prefrontal regions following alcohol consumption. Our findings add to this body of work by causally implicating activity in prefrontal regions with alcohol consumption behaviours. In conjunction with previous work, our findings suggest that applying TMS to the rDLPFC may inhibit neural activity and increase alcohol consumption. In light of research suggesting that left prefrontal regions are also associated with impairments in inhibitory control (Lowe et al., 2018) and appetitive craving (Lowe, Hall & Staines, 2014), future research also should examine the role of the lDPFC in alcohol consumption.

The current study found no direct effect of inhibitory control on alcohol consumption, and findings indicate that the association between cTBS of the rDLPFC and consumption did not appear to be mediated by impairments in inhibitory control. One explanation of this null finding is that inhibitory control may not be the central route through which rDLPFC exerts influence over alcohol consumption, and that other mechanisms (e.g., craving; Rose & Grunsell, 2008 or motivation; Rose et al., 2010) might play a more determinant role. Whilst not acting as a direct mediator, our findings may therefore indicate that inhibitory control acts via a different route, possibly as a “brake” on other cognitive and psychological mechanisms. For example, inhibitory control may moderate processes, such as automatic approach tendencies (Wiers et al., 2007) and implicit associations (Houben & Wiers, 2008). Nevertheless, this interpretation is merely speculative and future research with greater power is recommended to determine the extent to which inhibitory control is the primary mechanism by which the rDLPFC exerts influence over alcohol consumption, and the degree to which other cognitive processes may play a role.

Several limitations need to be borne in mind when considering current findings. First, the within-participants design limited our ability to analyze moderation although the sample size was in line with similar work (Lowe et al., 2018). Second, to prevent procedural signaling (Davies & Best, 1996) during the bogus taste task, we did not take measures of subjective craving or motivations to drink. This precludes our ability to assess the extent to which inhibitory control may exert a moderating influence. Third, the current study delivered SST shortly after stimulation to ensure that both the SST and the bogus taste task were conducted within appropriate time frames for effects of cTBS to be observed (~35-40 minutes). However, it is worth noting the findings from Huang et al. (2005), which suggest that the peak effects of 600 pulse cTBS occur at around 14-40 minutes poststimulation. Considering these previous findings, the null findings with regards to mediation in the current study warrant future investigations with longer delays prior to the delivery of cognitive tasks if procedural/technological advances make this feasible. Fourth, the current research used a student sample. University students are immersed in a heavy drinking culture (Borsari & Carey, 2001; Karam, Kypri, & Salamoun, 2007; Knight et al., 2002), and it is possible that findings may not generalize to other populations. Finally, the small sample size of the current study may be incompatible with detecting a small mediational effect, with post hoc power analysis suggesting that a sample of 200 may be required to detect an effect. However, it is worth noting that to our knowledge to date no such study testing the relationship between fluctuations in inhibitory control and subsequent alcohol consumption meet these power analysis requirements (Field & Jones, 2017, N = 81; Weafer & Fillmore, 2008, N = 26), and the current sample size is comparative with other TMS studies (Lowe et al., 2018: N’s = 7-40). In view of the amount of time required to conduct this kind of research, it may prudent for researchers to collaborate via multisite studies to address power concerns (Button et al., 2013).

In conclusion, the current study represents the first attempt to apply TMS to the rDLPFC to examine the resulting effect on actual alcohol consumption. Results point to the important role of this brain structure in shaping drinking behaviour as well as driving inhibitory control. However, inhibitory control was not found to mediate the observed association between stimulation of the rDLPFC and alcohol consumption, although future investigations with more highly powered designs could fruitfully revisit this hypothesis. Overall, our findings highlight that further research appears warranted to unpick the nuanced ways in which the rDLPFC and inhibitory control shape behaviours, which require the exertion of a degree of self-control.

References

Band, G. P. H., van der Molen, M W, & Logan, G. D. (2003). Horse-race model simulations of the stop-signal procedure. Acta Psychologica, 112(2), 105-142.

Bjork, J. M., & Gilman, J. M. (2014). The effects of acute alcohol administration on the human brain: Insights from neuroimaging. Neuropharmacology, 84, 101-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.07.039

Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2001). Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13(4), 391-424. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00098-0

Button, K. S., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Mokrysz, C., Nosek, B. A., Flint, J., Robinson, E. S. J., & Munafo, M. R. (2013). Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience (vol 14, pg 365-376, 2013). Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(6), 444. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3502

Caswell, A. J., Morgan, M. J., & Duka, T. (2013). Acute alcohol effects on subtypes of impulsivity and the role of alcohol-outcome expectancies. Psychopharmacology, 229(1), 21-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-013-3079-8

Cho, S. S., Ko, J. H., Pellecchia, G., Van Eimeren, T., Cilia, R., & Strafella, A. P. (2010). Continuous theta burst stimulation of right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex induces changes in impulsivity level. Brain Stimulation, 3(3), 170-176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2009.10.002

Christiansen, P., Cole, J., Goudie, A., & Field, M. (2012). Components of behavioural impulsivity and automatic cue approach predict unique variance in hazardous drinking. Psychopharmacology, 219(2), 501-510.

Christiansen, P., Rose, A. K., Cole, J. C., & Field, M. (2013). A comparison of the anticipated and pharmacological effects of alcohol on cognitive bias, executive function, craving and ad-lib drinking. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 27(1), 84-92.

Davies, J. B., & Best, D. W. (1996). Demand characteristics and research into drug use. Psychology & Health, 11(2), 291-299. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449608400258

De Wit, H. (2009). Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: A review of underlying processes. Addiction Biology, 14(1), 22-31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x

de Wit, H., & Richards, J. B. (2004). Dual determinants of drug use in humans: Reward and impulsivity. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 50, 19-55.

Fadardi, J. S., & Cox, W. M. (2008). Alcohol-attentional bias and motivational structure as independent predictors of social drinkers’ alcohol consumption. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 97(3), 247-256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.027

Field, M., & Jones, A. (2017). Elevated alcohol consumption following alcohol cue exposure is partially mediated by reduced inhibitory control and increased craving. Psychopharmacology, 234(19), 2979-2988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-017-4694-6

Field, M., Wiers, R. W., Christiansen, P., Fillmore, M. T., & Verster, J. C. (2010). Acute alcohol effects on inhibitory control and implicit cognition: Implications for loss of control over drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(8), 1346-1352.

Fillmore, M. T., & Rush, C. R. (2001). Alcohol effects on inhibitory and activational response strategies in the acquisition of alcohol and other reinforcers: Priming the motivation to drink. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62(5), 646-656.

Goudriaan, A. E., Oosterlaan, J., De Beurs, E., & Van Den Brink, W. (2006). Neurocognitive functions in pathological gambling: A comparison with alcohol dependence, tourette syndrome and normal controls. Addiction, 101(4), 534-547.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01380.x

Houben, K., & Wiers, R. W. (2008). Implicitly positive about alcohol? implicit positive associations predict drinking behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 33(8), 979-986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.002

Houben, K., Nederkoorn, C., & Jansen, A. (2014). Eating on impulse: The relation between overweight and food-specific inhibitory control. Obesity, 22(5), E8. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20670

Huang, Y. Z., Edwards, M. J., Rounis, E., Bhatia, K. P., & Rothwell, J. C. (2005). Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron, 45(2), 201-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.033

Jansen, J. M., Daams, J. G., Koeter, M. W. J., Veltman, D. J., van den Brink, W., & Goudriaan, A. E. (2013). Effects of non-invasive neurostimulation on craving: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(10), 2472-2480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.07.009

Jones, A., Christiansen, P., Nederkoorn, C., Houben, K., & Field, M. (2013). Fluctuating disinhibition: Implications for the understanding and treatment of alcohol and other substance use disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 4, 1-36. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00140

Karam, E., Kypri, K., & Salamoun, M. (2007). Alcohol use among college students: An international perspective. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20(3), 213-221.

Knight, J. R., Wechsler, H., Kuo, M., Seibring, M., Weitzman, E. R., & Schuckit, M. A. (2002). Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 63(3), 263-270. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2002.63.263

Lane, S. D., Cherek, D. R., Pietras, C. J., & Tcheremissine, O. V. (2004). Alcohol effects on human risk taking. Psychopharmacology, 172(1), 68-77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-003-1628-2

Lawrence, A. J., Luty, J., Bogdan, N. A., Sahakian, B. J., & Clark, L. (2009). Impulsivity and response inhibition in alcohol dependence and problem gambling. Psychopharmacology, 207(1), 163-172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-009-1645-x

Logan, G. D., Cowan, W. B., & Davis, K. A. (1984). On the ability to inhibit simple and choice reaction time responses: A model and a method. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 10(2), 276-291. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.10.2.276

Logan, G. D., Schachar, R. J., & Tannock, R. (1997). Impulsivity and inhibitory control. Psychological Science, 8(1), 60-64

Lowe, C. J., Hall, P. A., & Staines, W. R. (2014). The effects of continuous theta burst stimulation to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on executive function, food cravings, and snack food consumption. Psychosomatic Medicine, 76(7), 503-511. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000090

Lowe, C. J., Vincent, C., & Hall, P. A. (2017). Effects of noninvasive brain stimulation on food cravings and consumption: A meta-analytic review. Psychosomatic Medicine, 79(1), 2-13. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000368

Lowe, C. J., Manocchio, F., Safati, A. B., & Hall, P. A. (2018). The effects of theta burst stimulation (TBS) targeting the prefrontal cortex on executive functioning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia, 111, 344-359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.02.004

Luijten, M., Schellekens, A. F., Kuehn, S., Machielse, M. W. J., & Sescousse, G. (2017). Disruption of reward processing in addiction an image-based meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Jama Psychiatry, 74(4), 387-398. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3084

Montoya, A. K., & Hayes, A. F. (2017). Two-condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: A path-analytic framework. Psychological Methods, 22(1), 6-27. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000086

Murphy, P., & Garavan, H. (2011). Cognitive predictors of problem drinking and AUDIT scores among college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 115(1-2), 94-100.

Nederkoorn, C., Baltus, M., Guerrieri, R., & Wiers, R. W. (2009). Heavy drinking is associated with deficient response inhibition in women but not in men. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 93(3), 331-336.

Nigg, J. T., Wong, M. M., Martel, M. M., Jester, J. M., Puttler, L. I., Glass, J. M., . . . Zucker, R. A. (2006). Poor response inhibition as a predictor of problem drinking and illicit drug use in adolescents at risk for alcoholism and other substance use disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(4), 468-475.

Olmstead, M. C. (2006). Animal models of drug addiction: Where do we go from here? Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology (2006), 59(4), 625-653.

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S., & Barratt, E. S. (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51(6), 768-774

Pridmore, S., Fernandes, J. A., Nahas, Z., Liberatos, C., & George, M. S. (1998). Motor threshold in transcranial magnetic stimulation: A comparison of a neurophysiological method and a visualization of movement method. Journal of Ect, 14(1), 25-27.

Rose, A. K., & Duka, T. (2006). Effects of dose and time on the ability of alcohol to prime social drinkers. Behavioural Pharmacology, 17(1), 61-70.

Rose, A. K., & Grunsell, L. (2008). The subjective, rather than the disinhibiting, effects of alcohol are related to binge drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(6), 1096-1104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00672.x

Rose, A. K., Hobbs, M., Klipp, L., Bell, S., Edwards, K., O’Hara, P., & Drummond, C. (2010). Monitoring drinking behaviour and motivation to drink over successive doses of alcohol. Behavioural Pharmacology, 21(8), 710-718. https://doi.org/10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833fa72b

Rossi, S., Hallett, M., Rossini, P. M., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2009). Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.016

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., de la Fuente, J., & Grant, M. (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption: II. Addiction, 88(6), 791-804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x

Sobell, L. C., & Sobell, M. B. (1990). Self-report issues in alcohol abuse: State of the art and future directions. Behavioral Assessment, 12(1), 77-90.

Verbruggen, F., Logan, G. D., & Stevens, M. A. (2008). STOP-IT: Windows executable software for the stop-signal paradigm. Behavior Research Methods, 40(2), 479-483. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.2.479

Volkow, N. D., Ma, Y., Zhu, W., Fowler, J. S., Li, J., Rao, M., . . . Wang, G. (2008). Moderate doses of alcohol disrupt the functional organization of the human brain. Psychiatry Research-Neuroimaging, 162(3), 205-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.04.010

Volkow, N. D., Koob, G. F., & McLellan, A. T. (2016). Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(4), 363-371. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1511480

Wassermann, E. M. (1998). Risk and safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: Report and suggested guidelines from the international workshop on the safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, June 57, 1996. Electroencephalography & Clinical Neurophysiology: Evoked Potentials, 108(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-5597(97)00096-8

Weafer, J., & Fillmore, M. T. (2008). Individual differences in acute alcohol impairment of inhibitory control predict ad libitum alcohol consumption. Psychopharmacology, 201(3), 315-324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-008-1284-7

Weafer, J., & Fillmore, M. T. (2012). Alcohol-related stimuli reduce inhibitory control of behavior in drinkers. Psychopharmacology, 222(3), 489-498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-012-2667-3

Weafer, J., & Fillmore, M. T. (2013). Acute alcohol effects on attentional bias in heavy and moderate drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(1), 32-41. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028991

Wiers, R. W., Bartholow, B. D., van, DW, Thush, C Engels, Rutger C M E, Sher, K. J., … Stacy, A. W. (2007). Automatic and controlled processes and the development of addictive behaviors in adolescents: A review and a model. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 86(2), 263-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2006.09.021

World Health Organization. (2014). Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. Albany: World Health Organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and declare that this paper is not under review or in press at any other journal, nor will it be submitted elsewhere until the completion of the decision-making process.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

McNeill, A., Monk, R.L., Qureshi, A.W. et al. Continuous Theta Burst Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Impairs Inhibitory Control and Increases Alcohol Consumption. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 18, 1198–1206 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-018-0631-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-018-0631-3