Abstract

The influence of ruderal species and crop density on ancient segetal weeds was examined. The experiment was carried out on experimental plots with three different sewing densities of winter triticale. Weeding of ruderal taxa was applied on half of the plots to explore the relation between segetal and ruderal weeds. Variation in species composition by environmental variables was analysed by running Redundancy Analysis (RDA) combined with performing forward selection and variation partitioning for “weeding” and “crop density” as explanatory variables. Additionally, the effect of crop density and weeding was tested separately for segetal and ruderal species along the seasons with the use of co-variance analysis (ANCOVA). The overall species composition changes due to crop density and weeding revealed by the redundancy analysis were significant, with the total explained variation of 15.7%. The authors found that crop density has a stronger influence on species composition than weeding (56.2% vs. 47.2%). Weeding increases mean segetal weed cover from ca. 19% to more than 35%. Along the vegetation period, weeding has an increasing explanatory power, with the highest scores in the autumn. The combined effect of both variables explains the highest share of variation for summer data (54%), then for autumn (40%), and spring (35%). Crop density is much more influential on segetal weeds, dropping inconsiderably from spring to summer and then abruptly in autumn. For several species we found the optimum crop density being a loose stand with ca. 20–40% cover (e.g. for Agrostemma githago).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent decades have brought significant changes to global biodiversity and led to programs aimed at reducing the loss of this natural world heritage, particularly in segetal ecosystems (Meyer et al. 2013; Richner et al. 2015). During the twentieth century the intensification of cultivation techniques and weed control have caused significant changes in weed flora and a severe decline of many archaeophytes – typical segetal weeds of ancient origin (Kolářová et al. 2013). The agricultural market and economy force farmers to cultivate very limited varieties of profitable crop plants and to abandon traditional crops such as flax. This contributes considerably to the decrease of weed species within a stand (Knox et al. 2011). Recently, the decline of segetal weeds has been recorded and the endangerment of archaeophytes have been highlighted in many countries (e.g. Eliáš et al. 2007; Zając et al. 2009; Pinke et al. 2011). In southern Poland, the most threatened group of archaeophytes includes the calcicole taxa such as Adonis aestivalis L., Anagallis foemina Mill. Bupleurum rotundifolium L., Caucalis platycarpos L., and Scandix pecten-veneris L. (Nowak 2007).

The response of segetal weeds to cultivation intensification differs in relation to their biological and functional traits, as well as their origin and time of arrival. Despite the plants coming from a local species pool that adapt to the arable field disturbances, the remaining group is commonly divided into archaeophytes (ancient weeds) that were introduced between the Neolith (ca. the sixth millennium BC in Central Europe) and the discovery of America, and neophytes that were established after 1500 (Pyšek et al. 2002). Weeds, particularly archaeophytes, have evolved over the long period of crop cultivation and throughout the history of agriculture. It was shown that these three groups of species respond to variables such as climate, altitude, human population density, and crop cover in different ways (Pyšek et al. 2005). As the number and abundancy of archaeophytes decrease, the neophytes and ruderal plants increase for both parameters (e.g. Májeková et al. 2010). The number and proportion of nitrophilous ruderals in Czech republic increased in 1955–2000, whereas the number of native species and archaeophytes declined, which is mainly explained by human population density and agricultural intensification. Archaeophytes have a relatively larger representation in cereals, in contrast to neophytes that prefer more recently introduced crops such as rape or maize. The old-comers are in the majority annuals with their life cycle suited to the crop plant. The newcomers and ruderals are often perennials able to settle in variable habitats that are exposed to disturbances such as balks, waste dumps, road verges, but also arable fields, particularly those with a high intensity of agriculture (Nowak 2007).

Despite the different cultivation practices, crop type, and herbicide use, one of the most important variables that strongly influences the weed abundance is crop stand density. It has been reported that weed biomass and other measures of weed abundance usually decrease with increasing crop density (Mohler 2004). However, the majority of studies have been devoted to finding the yield losses as a result of weed encroachment, or have analysed the single taxon or a group of common species (Mohler 2004).

The importance of interspecific competition between species, particularly crop plant and weeds, as a selective factor in forming species assemblages has been recognized since the beginning of the natural selection theory. Understanding the processes that govern plant community assembly is of crucial importance when studying natural successional or secondary community development (Moore and Franklin 2012). These processes could explain the changes in species composition in human-made habitats, particularly if weeding is implemented to ease the development of species from the local species pool, or to trigger an increase in the abundance of co-occurring taxa within a plot.

Invasive neophytes or ruderal plants have attracted great attention because they usually have a significant ecological impact and generate considerable economic costs (Pimentel et al. 2005). They are considered to pose a serious problem for biodiversity conservation and to be a significant driver in the decline of global species diversity (Mack et al. 2000). Man-made habitats are particularly prone to alien species invasions and ruderal species encroachment as a result of the application of nitrogen fertilizers (Pyšek et al. 2005; Májeková et al. 2010). Although the loss of phytodiversity in arable lands has recently received considerable attention, particularly on a landscape scale, little is known about the direct competition and influence of crop stand density on archaeophytes and ruderal taxa (including neophytes) in an experimental study (Lososová and Simonová 2008). Therefore, in our study we focused on stand density as one of the main drivers of weed abundance and diversity. On the one hand, crop density influences the weed plant community by its competitive abilities for food resources, light and space, but on the other hand it sustains the coevolved species, suppresses their strongest competitors and protects weeds against unsuitable environmental conditions (e.g. drought, wind). The second factor that have been subjected to our investigation is the encroachment of ruderal plants that are known to have the potential to outcompete segetal archaeophytes from intensively cultivated habitats, including crops (Májeková et al. 2010).

We established an experimental field located in an urban site and examined the effect of particular explanatory variables in the experiment that mimics the real crop stand situation. The present paper attempts to answer the following questions: (1) What mostly influences the number and cover of archaeophytes, the crop stand density or ruderal species on arable land? (2) What is the influence of ruderal species to old-comers in relation to crop density? (3) What is the optimal crop stand density for selected rare archaeophyte plants?

Methods

Study area and experiment design

The experiment was established in summer 2014 in the Silesian Village Open Air Museum in Opole-Bierkowice. The experimental field was supplied with rendzina soil from the nearby Krzanowice village. This location is known for the richest weed communities in the region (Nowak 2007). On the area of 50 m2, 40 plots of 1.0 m2 were created with a soil layer horizon of 40–45 cm. Paths were planned between these plots to allow access and ease of sampling of the species data and weeding (Figs. 1 and 2). In October 2014 winter triticale (×Triticosecale) was sown in three different densities: 375, 750 and 1500 seeds per plot. One subset of plots was left without a crop stand. Despite the translocated soil being rich in rare weed species, we collected seeds of selected archaeophytes and sowed them randomly one year before the experiment on the whole studied plot. We used ca. 100,000 Agrostemma githago seeds, 10,000 Bupleurum rotundifolium seeds, 1500 Scandix pecten-veneris seeds, and 200 Caucalis platycarpos seeds. Weeding was applied to half of the plots. All the ruderal taxa were picked up and eliminated as seedlings from the plots every month from March to October. The weeding was applied in a half of the experimental field, in each subplot from the pair of plots with the same crop density (Fig. 2).

Sampling and species classification

Sampling was conducted during the vegetation season from April to October 2015. In the middle of every month, in one day, the composition and cover of all the vascular plants were assessed in each plot with the use of a percentage scale. In the experiment the crop stand was harvested at the same time as in neighboring fields – at the end of August – with the use of a sickle. This allows not only the spring and summer but also the stubble weed communities to develop. Altogether, 38 ruderal species (including neophytes) were eliminated. They have the optimum of occurrence in Artemisietalia vulgaris and Onopordetalia acanthii vegetation in the Silesian flora. Additionally, the species of trampled habitats were weed out as expansive in the field margins and with strong competitive abilities (Plantaginetalia majoris; Matuszkiewicz 2013). The species nomenclature was applied after Mirek et al. (2002).

Statistical analyses

To summarize the part of the variation in species composition explained by environmental variables, constrained analysis with weeding and crop density as explanatory variables was applied. The species data showed a unimodal response (1.8 SD unit for the whole data set), enabling the authors to use Redundancy Analysis (RDA). For standardizing the response variables, the log-transformation was conducted and further computing launched without down weighting the rare species. To test the axes significance, the Monte Carlo permutation test was executed with 499 repeats, and only the predictors with a significance of p < 0.05 were included in the RDA model. The cover of ruderal species, segetal weeds and total weed cover were passively projected as supplementary variables. Every cover value of a particular group was derived from the six monthly values across the season as a weighted average. To find the unique explanatory contribution of the two environmental variables (crop density and weeding), we performed an interactive forward selection to find the most powerful factors and then conducted variation partitioning. On the graphs only 35 taxa with the highest fit scores were presented. For the computation of species response curves for the target taxa (e.g. Agrostemma githago, Bupleurum rotundifolium, Caucalis platycarpos, and Scandix pecten-veneris), the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) was applied. Canoco for Windows 5 was used for all ordinations (ter Braak and Šmilauer 2012).

The effect of the crop density (continuous predictor variable) and weeding (categorical predictor variable) was tested separately for the segetal and ruderal species covers (independent variables) within the studied plots. Initially, the interactions between the categorical/continuous predictors and independent variable were tested to verify the homogeneity of the regression slopes under the general linear model (GLM). The combined and unique effect of the predictor variables (i.e., crop density and weeding) on the independent variables (i.e., segetal and ruderal weeds) was analysed in separate analyses of co-variance (ANCOVAs). The Levene’a and Shapiro-Wilk tests for checking the homogeneity and normality within the data set, and the Tukey post-hoc test to check the significance of differences, were used. Statistical calculations were performed using Statistica software ver. 9.1. The comparisons of means of the covers of particular group of species (segetal archaeophytes vs. ruderals) were conducted with the use of non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test for differences in weeded and not weeded plots and Wilcoxon pairwise test for covers in different crop densities.

To determine the seasonality and compositional changes in species composition during the experiment, we conducted the analysis for the whole data set and for a particular season. For spring, we used data from the April and May sampling, for summer – data from June, July and August, and for autumn – data from the October sampling from the stubble fields with the so-called “autumn aspect”.

Results

Influence of crop density and weeding on species composition in weed communities

The overall species composition changes due to crop density and weeding revealed by the redundancy analysis is significant (total explained variation 15.7%, F = 4.6, p = 0.001). The most powerful effect on species composition has crop density as it counts for 56.2% of the explained variation (F = 5, p = 0.001). The suppressing of competitive power of ruderal species by weeding is responsible for 47.2% of the explained variation (F = 4.3, p = 0.001). Among species that reveal the strongest response to ruderal weed elimination are Agrostemma githago, Bupleurum rotundifolium, Caucalis platycarpos, Papaver argemone, Scandix pecten-veneris, Setaria viridis and Veronica persica (Figs. 3 and 4). In plots that were not subjected to weeding the Melilotus officinalis, Fallopia convolvulus, Chenopodium album, Euphorbia peplus, Convolvulus arvensis and Polygonum aviculare achieve the considerable abundances. As regards the response to crop density, the most positively related taxa with lose stands or with plots without any crop were Caucalis platycarpos, Fumaria vailantii, Papaver argemone, P. rhoeas, Scandix pecten-veneris and Viola arvensis. Dense crop stands can withstand only few taxa: Artemisia vulgaris, Euphorbia peplus, Glechoma hederacea and Veronica persica.

Results of redundancy analysis (RDA) showing the influence of crop density and weeding on species composition. The cover of ruderal and segetal species and the total weed cover were plotted passively in the graph. Only 30 species with the highest fit scores were shown. The total variation is 610.74, explanatory variables account for 20%, the adjusted explained variation is 15.6%. N – without weeding, W – with weeding. Weed_cov – weed cover, Seg_cov – segetal weed cover, rud_cov – ruderal weed cover, Crop_den – crop density

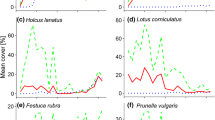

Examples of species response curves showing the probability of occurrence along with increasing crop density. Examples of segetal weeds with optimum in loose stands are shown (Agrostemma githago, Melandium noctiflorum, Sherardia arvensis and Veronica arvensis), weeds with decreasing abundancies along with increasing crop density (Bupleurum rotundifolium, Caucalis platycarpos and Scandix pecten-veneris) and these that prefer denser crop stands (Amaranthus retroflexus and Chenopodium album)

The relation between “good weeds” (segetal archaeophytes) and “bad weeds” (ruderals) in the experimental plots

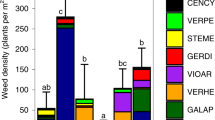

Weeding cause the considerable difference in mean segetal weed cover. It increases from approx. 19% in not weeded plots to more than 35% in weeded (p < 0.05; Fig. 5). As it could be expected, the ruderal weed cover decrease respectively from 33% to 18% (p < 0.05; Fig. 5). The correlation coefficient for this group of species equals −0.35, p < 0.05 (Fig. 6). It is interesting that ancient segetal archaeophytes achieve much higher covers in plots without crop with mean approx. 40% in comparison to 26% for ruderals (p < 0.05) This proportion is sustained to some extent in plots with low crop density (means respectively 24% and 21%; p < 0.05), but then reverts and ruderal weeds take advantage in moderately dense stands (23% vs. 24%; p < 0.05) and the densest crops (16% vs. 22%; p < 0.05).

The means of segetal and ruderal weed cover on weeded and not weeded plots in the whole season (WS|) and for spring (Sp), summer (Su) and autumn (Au). All season pair means were significantly different with exception of ruderal weeds for spring (for segetal weeds F = 11.54, p < 0.001; for ruderal weeds F = 60.30, p < 0.001)

Seasonal variation in segetal and ruderal weed covers and the influence of weeding and crop density

The abundancy of segetal weeds drops along the season. Only in weeded plots does it achieve a peak in the summer (38%), however also in the spring the means are not much lower (37%; Fig. 5). The difference of ancient segetal weeds between weeded and non-weeded plots has the highest value in the summer (ca. 24%) and drops to 8% in the autumn. The scores of ruderal weeds are different. They also reach a peak of abundancy in the summer, but the lowest in the spring. Generally, weeding has an increasing explanatory power along the seasons, with the highest scores in the autumn. The combined effect of both variables explains the highest share of variation for the summer data (54%), then for the autumn (40%) and lastly for the spring (35%; Table 1). Crop density is much more influential on segetal weeds (partial regression coefficient − 0.73 vs. -0.13 for ruderals for the whole data set), and drops slightly from spring (−0.66, p < 0.001) to summer (−0.63, p < 0.001) and abruptly in autumn (−0.25, p < 0.001; Table 2). Weeding supports the populations of segetal weeds to the highest extent in the spring (0.75, p < 0.001), with a considerable decrease in power of influence in the summer and autumn.

Discussion

Majority of segetal weeds can thrive without crop stand

Segetal weeds, particularly those inhabiting cereal fields, have a long history of co-occurrence with crops, and reveal a range of adaptations to avoid being suppressed by the crop (Goldberg and Landa 1991). For a number of segetal weeds, speciation has been triggered by specific disturbance inherently linked to field ecosystem management. The so-called anthropophyta anthropogena exclusively inhabit crop phytocoenoses and, due to agriculture intensification, have suffered in the last few decades, with many of them even disappearing (Heller 2010; José-María et al. 2010). As the decline of ancient weeds has become a serious global conservation problem (Cirujeda et al. 2011; Meyer et al. 2013), in our experiment we wanted to find the optimal crop density to sustain the weed population, in particular the disappearing ancient weeds from the archaeophyte group. Our results are generally in line with the known relation that increasing crop density hampers weed abundance. The responsible factor is that crops are more effective in soil nutrients uptake and limit access to light (Tang et al. 2014). However, this rule only holds true for archaeophytes in our experiment. Ruderal taxa do not reveal significant change in cover in crop stands of different density. Most probably the archaeophytes recruitment is related to the soil seed bank of the experimental field so that they can germinate in early spring and achieve a considerable share in the main season. Whereas the ruderals, at least to some extent, arrive from neighboring lands and reach their peak of abundance in late summer or in the stubble field.

Focusing on the ancient weeds, the decreasing abundance is surely related to stronger competition for light, water, and resources with crops (Rotchés-Ribalta et al. 2016). As the competition of ruderals is not so significant, the crops are the most important competitor that constrain resources availability. Nevertheless, this obvious pattern – the long lasting coevolution of crops with an ancient weed – should bring some adaptation regarding the co-occurrence of weeds and crops. Indeed, there are species that do not follow this simple correlation. For example, Agrostemma githago inevitably has the optimum of occurrence in low density crops (Fig. 4). This is linked to the supporting role of the crop plant in withstanding the wind pressure. A crop canopy is also preferred by Melandrium noctiflorum and Sherardia arvensis. Thus, at least for some taxa crops facilitate the growth of highly specialized species. This phenomenon is well known in other types of ecosystems where the canopy (generally the tree layer) facilitates the encroachment and development of taxa from neighboring vegetation types (Dohn et al. 2013).

Astonishingly, the ancient weeds achieve the highest abundance not in low density stands but in plots without any cover of cultivated plants (exept Agrostemma githago). This could partially be explained by the low competition from ruderals that have twice lower abundance in plots without a crop. It can be linked to the smaller seed bank size of ruderals in the field, and with the phenological shift of the abundance peak of ruderals to autumn (Gallinat et al. 2015). Another explanation for the high cover of archaeophytes in a bare arable field is that many of them reveal the creeper morphology (e.g. Fallopia convolvulus) or have small sizes (e.g. Euphorbia exigua and Sherardia arvensis), and do not need to be supported by the crop plant as do the taller weeds. This group of plants can be successful in occupying bare arable lands, at least in the first year. This result can be used in the conservation of ancient weed diversity. The narrow strips of ground along the balks, if left bare with no crops, however regularly ploughed, can harbor a number of ancient weeds (Cirujeda et al. 2011; Meyer et al. 2014).

Density of crop stand explains the good weed abundance better than ruderal weed encroachment

Weeds differ in their response to man-made changes in the environment. It has been shown in several studies that ancient weeds generally declined (Preston et al. 2004), while the frequency and abundance of neophytes tended to increase (Pyšek et al. 2005; Lososová and Simonová 2008; Májeková et al. 2010). The “good weeds” (archaeophytes) are outcompeted in arable lands by ruderal species (including neophytes) or segetal weeds that are more resistant to herbicides (Šilc and Čarni 2005; Meyer et al. 2013). However, there are also studies showing a similar pattern of the vanishing of neophytes suffering from modern cultivation methods. An example is Veronica persica that decreased in eastern Germany by 40% (Meyer et al. 2013). The results of comparison between ruderal weeds and crop density show no significant correlation, with a slightly higher cover of ruderals in denser stands. This shows that the crop density and its competitive power controls both ancient and ruderal weeds. But the archaeophytes tend to disappear in much denser stands, while ruderals have generally lower abundance, equal in crops of different densities. This implies that making strips of bare lands for ancient weeds recovery does not cause a considerable risk of ruderal species intensive encroachment (Duru et al. 2015; Rollin et al. 2016).

Along the year the good weeds dominate in spring and summer, the bed weeds in autumn

Plant response to tillage includes germination syndrome and life cycle, both of which influence how species respond to changes in soil resource levels, aeration, damage to underground plant organs, and light availability driven by seasonal disturbance regime. Ancient weeds are well adapted to tillage as they have 10,000 years of history of coevolution with crops (Pyšek et al. 2005); they prefer arable lands and are strong competitors in early spring and summer when their seed cohorts begin to germinate. Ruderal weeds reveal a different phenology that is probably linked with their different habitat preferences. This kind of niche separation for alien species and phenological temporal shift in blossom periods was found in urbanized areas in Italy (Celesti-Grapow et al. 2003). It can be caused by the specific, different biology of both species groups, but also by selecting aliens for apiculture. Bee-keepers wanted to extend the blooming season so they introduced exotic taxa that have a flowering peak period in late summer and autumn. Many of them successfully escaped and then were established in different habitats. This is clearly visible in our experiment, however not many ruderal species found in the plots were typical late-flowering ones, but they achieved considerable abundancies (e.g. Amaranthus retroflexus, Atriplex oblongifolia, Melilotus officinalis). Moreover, the elongated autumn and extended flowering period in the last few years (Gallinat et al. 2015; Rafferty and Nabity 2017) has allowed for the producing of mature seeds and gaining an advantage over native species due to the extended autumnal growth. Another possible explanation is that the separated flowering of native and exotic species may be related to selection and competition with local plants so as to avoid interspecific competition with native vegetation.

Conclusion

This study is the first attempt to explore the relation between expansive ruderal species and withdrawing ancient weeds in crops with different densities. The authors found that crop density controls both archaeophytes and ruderal species abundancies. After applying weeding in order to eliminate the competitors of ancient weeds, we discovered that the density of crop stand is the major factor that causes the withdrawal and decline in the diversity of “good weeds”. Within a group of target taxa, we indicate for several (e.g. Agrostemma githago and Melandrium noctiflorum) the optimum crop stand density and show the seasonal variability of “good” as well as “bad” weeds. Both results can be used in the application of sustainable agriculture, particularly in creating marginal diversity strips and optimizing weed control in relation to the ecosystem services supported by field plants.

References

Celesti-Grapow L, Marzio P, Blasi C (2003) Temporal niche separation of the alien flora of Rome (Italy). In: Child L, Brock JH, Brundu G, Prach K, Pysĕk K, Wade PM, Williamson M (eds) Plant invasions: ecological threats and management solutions. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, pp 101–111

Cirujeda A, Aibar J, Zaragoza C (2011) Remarkable changes of weed species in Spanish cereal fields from 1976 to 2007. Agron Sustain Dev 31:675–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-011-0030-4

Dohn J, Dembélé F, Karembé M, Moustakas A, Amévor KA, Hanan NP (2013) Tree effects on grass growth in savannas: competition, facilitation and the stress-gradient hypothesis. J Ecol 101:202–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12010

Duru M, Therond O, Martin G, Martin-Clouaire R, Magne MA, Justes E, Journet EP, Aubertot JN, Savary S, Bergez JE, Sarthou JP (2015) How to implement biodiversity-based agriculture to enhance ecosystem services: a review. Agron Sustain Dev 35:1259–1281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-015-0306-1

Eliáš P, Eliáš P, Baranec T (2007) New red list of Slovak threatened weeds. In: Eliáš P (ed) Threatened weedy plant species. Slovak University of Agriculture, Nitra, pp 23–28

Gallinat AS, Primack RB, Wagner DL (2015) Autumn, the neglected season in climate change research. Trends Ecol Evol 30:169–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2015.01.004

Goldberg DE, Landa K (1991) Competitive effect and response: hierarchies and correlated traits in the early stages of competition. J Ecol 79:1013–1030. https://doi.org/10.2307/2261095

Heller K (2010) “Flax specialists” - weed species extinct in Poland? Plant Breed Seed Sci 61:35–40. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10129-010-0010-x

José-María L, Armengot L, Blanco-Moreno JM, Bassa M, Sans FX (2010) Effects of agricultural intensification on plant diversity in Mediterranean dryland cereal fields. J Appl Ecol 47:832–840. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01822.x

Knox OGG, Leake AR, Walker RL, Edwards AC, Watson CA (2011) Revisiting the multiple benefits of historical crop rotations within contemporary UK agricultural systems. J Sustain Agric 35:163–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/10440046.2011.539128

Kolářová M, Tyšer L, Soukup J (2013) Impact of site conditions and farming practices on the occurrence of rare and endangered weeds on arable land in the Czech Republic. Weed Res 53:489–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/wre.12045

Lososová Z, Simonová D (2008) Changes during the 20th century in species composition of synanthropic vegetation in Moravia (Czech Republic). Preslia 80:291–305

Mack RN, Simberloff D, Lonsdale MW, Evans H, Clout M, Bazzaz FA (2000) Biotic invasions: causes, epidemiology, global consequences, and control. Ecol Appl 10:689–710. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9623(2005)86[249b:IIE]2.0.CO;2

Májeková J, Zaliberová M, Šibík J, Klimová K (2010) Changes in segetal vegetation in the Borská nížina lowland (Slovakia) over 50 years. Biologia 65:465–478. https://doi.org/10.2478/s11756-010-0035-5

Matuszkiewicz W (2013) Przewodnik do oznaczania zbiorowisk roślinnych Polski. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa

Meyer S, Wesche K, Krause B, Leuschner C (2013) Dramatic losses of specialist arable plants in Central Germany since the 1950s/60s - a cross-regional analysis. Divers Distrib 19:1175–1187. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12102

Meyer ST, van Elsen B, Blümlein M, Kaerlein J, Metzger F, Gottwald S, Wehke M, Dieterich W, Wahmhoff R, Stock R, Leuschner C (2014) Conserving agrobiodiversity through arable field sanctuaries. Natur und Landschaft 9:434–441. https://doi.org/10.17433/9.2014.50153301

Mirek Z, Piękoś-Mirkowa H, Zając A, Zając M (2002) Flowering plants and pteridophytes of Poland. A checklist. In: Mirek Z (ed) Biodiversity of Poland 1. W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, Kraków

Mohler CL (2004) Enhancing the competitive ability of crops. In: Liebman M, Mohler CL, Staver CP (eds) Ecological Management of Agricultural Weeds. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 269–321

Moore JE, Franklin SB (2012) Water stress interacts with early arrival to influence interspecific and intraspecific priority competition: a test using a greenhouse study. J Veg Sci 23:647–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2012.01388.x

Nowak S (2007) Zróżnicowanie agrofitocenoz obszaru występowania wychodni skał węglanowych na Śląsku Opolskim. Uniwersytet Opolski, Opole

Pimentel D, Zuniga R, Morrison D (2005) Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecol Econ 52:273–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.10.002

Pinke G, Király G, Barina Z, Mesterházy A, Balogh L, Csiky J, Schmotzer A, MolnáR AV, Pál RW (2011) Assessment of endangered synanthropic plants of Hungary with special attention to arable weeds. Plant Biosyst 145:426–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/11263504.2011.563534

Preston CD, Pearman DA, Hall AR (2004) Archaeophytes in Britain. Bot J Linn Soc 145:257–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2004.00284.x

Pyšek P, Sádlo J, Mandák B (2002) Catalogue of alien plants of the Czech Republic. Preslia 74:97–186

Pyšek P, Jarošík V, Chytrý M, Kropáč Z, Tichý L, Wild J (2005) Alien plants in temperate weed communities: prehistoricand recent invaders occupy different habitats. Ecology 86:772–785. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-0012

Rafferty NE, Nabity PD (2017) A global test for phylogenetic signal in shifts in flowering time under climate change. J Ecol 105:627–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12701

Richner N, Holderegger R, Linder HP, Walter T (2015) Reviewing change in the arable flora of Europe: a meta-analysis. Weed Res 55:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/wre.12123

Rollin O, Benelli G, Benvenuti S, Decourtye A, Wratten SD, Canale A, Desneux N (2016) Weed-insect pollinator networks as bio-indicators of ecological sustainability in agriculture. A review Agron Sustain Dev 36:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-015-0342-x

Rotchés-Ribalta R, Blanco-Moreno JM, Armengot L, Sans FX (2016) Responses of rare and common segetal species to wheat competition and fertiliser type and dose. Weed Res 56:114–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/wre.12191

Šilc U, Čarni A (2005) Changes in weed vegetation on extensively managed fields of Central Slovenia between 1939 and 2002. Biologia 60:409–416

Tang L, Cheng C, Wan K, Li R, Wang D, Tao Y, Pan J, Xie J, Chen F (2014) Impact of fertilizing pattern on the biodiversity of a weed community and wheat growth. PLoS One 9(1):e84370. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084370

Ter Braak CJF, Šmilauer P (2012) Canoco reference manual and user's guide: software for ordination, version 5.0. Microcomputer Power, Ithaca

Zając M, Zając A, Tokarska-Guzik B (2009) Extinct and endangered archaeophytes and the dynamics of their diversity in Poland. Biodiv Res Conserv 13:17–24. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10119-009-0004-4

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the employees of the Silesian Village Open Air Museum in Opole-Bierkowice and Mr. Andrzej Rybarczyk, Director of the Opole Cement Factory Ltd., for their help in the preparation and conducting of the experiment.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, project No 2017/25/B/NZ8/00572.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nowak, S., Waindzoch, K., Świerszcz, S. et al. Crop density rather than ruderal plants explains the response of ancient segetal weeds. Biologia 74, 351–359 (2019). https://doi.org/10.2478/s11756-018-00178-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2478/s11756-018-00178-8