Abstract

High-rate lithium ion batteries with long cycling lives can provide electricity grid stabilization services in the presence of large fractions of intermittent generators, such as photovoltaics. Engineering for high rate and long cycle life requires an appropriate selection of materials for both electrode and electrolyte and an understanding of how these materials degrade with use. High-rate lithium ion batteries can also facilitate faster charging of electric vehicles and provide higher energy density alternatives to supercapacitors in mass transport applications.

High-rate lithium ion batteries can play a critical role in decarbonizing our energy systems both through their underpinning of the transition to use renewable energy resources, such as photovoltaics, and electrification of transport. Their ability to be rapidly and frequently charged and discharged can enable this energy storage technology to play a key role in stabilizing future low-carbon electricity networks which integrate large fractions of intermittent renewable energy generators. This decarbonizing transition will require lithium ion technology to provide increased power and longer cycle lives at reduced cost. Rate performance and cycle life are ultimately limited by the materials used and the kinetics associated with the charge transfer reactions and ionic and electronic conduction. We review material strategies for electrode materials and electrolytes that can facilitate high rates and long cycle lives and discuss the important issues of cost, resource availability and recycling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In an 1883 interview, Thomas Edison said of energy storage1:

“Scientifically, storage is all right, but, commercially, as absolute a failure as one can imagine. You can store it and hold, it, but it is gradually lost, and will all go in time. Its efficiency, after a certain number of charges have been sustained, begins to diminish, and its capacity and efficiency both diminish after a certain time in use, necessitating an increased number of batteries to maintain a constant output.”

More than 130 years on, electrochemical energy storage is now poised to play a critical role in decarbonizing our energy systems, both through its underpinning of the transition to use renewable energy resources, such as photovoltaics (PV), and its central role in electrification of transport.2 Although, to-date, battery technology development has been driven by the miniaturization of mobile electronics and, more recently, energy storage for electric vehicles (EVs), it is becoming increasingly important to consider also its role in electricity generation from low-carbon energy resources. Without wide- scale replacement of fossil fuels with near-zero carbon energy sources for electricity generation, the life cycle emission damages that result from battery production and charging can be greater for plug-in hybrid and full-battery EVs than for hybrid EVs due to the emissions from coal-fired power plants used for electricity generation.3,4

PV is the fastest growing renewable energy technology (40% per year over the last decade5–7) and has the fastest manufacturing experience (learning) rate of all renewable energy technologies (22.8% over the past 40 years8). By 2050, PV could supply 30-50% of the world’s electricity, with the levelized cost of electricity from PV expected to be in the range of US$0.02-$0.06/kWh.7 Especially for regions in the “sun belt” (see Fig. 1), PV provides a valuable and cost-effective means to contribute to the decarbonization of the electricity sector, especially if part of a mix of near-zero carbon electricity generators.7,9–11 Unlike fossil fuel resources, solar energy is ubiquitous, and so once a PV system has been installed, the price of the electricity generated is predictable and not subject to resource pricing changes.12 This can provide a global energy stability that has not previously been possible with energy systems that rely on resources distributed unevenly across the world.2

The energy storage attributes required to facilitate increased integration of PV in electricity grids are not generally well understood. While load shifting and peak shaving of residential PV generation13–17 may be achieved using batteries with relatively low power rates, power generation from solar PV can change unpredictably on sub-second time scales18–22 and destabilize electricity networks. In the absence of technological solutions, this unpredictable intermittence can limit penetration levels of PV and indeed also other intermittent resources, such as wind. However, there is another view that use of wind and PV in concert with parallel grid-forming inverters23–26 and rapidly responding frequency stabilization services that utilize energy storage17,22,27–33 can enable more flexible and resilient electricity grids.2,17 With the rapid reduction in costs of PV that are occurring, reduced and sustainable electricity prices may be possible and the full advantages of transport electrification can be realized.

Lithium ion batteries (LIBs)34–36 have been identified as the most promising option for high-rate energy storage (i.e., fast charging and high power) at acceptable cost.22,30,33,35,37-41 In a comparison of the ability of selected electrochemical energy storage technologies to maintain the inherent power fluctuations of PV systems to within acceptable ramp rates of <10%/min, Jiang et al. found that high-rate LIBs required a smaller battery volume compared to other energy storage technologies when high compliance levels were required.22 For the particular case of a 7.2 MW PV system (covering an area of52 Ha), use of a high-rate LIB required only ~40% and ~4% of the volume of a high-energy LIB and a lead acid battery, respectively, to maintain the ramp rate wit hin <10%/ min with 99% compliance (see Fig. S1). This significantly reduced volume, taken together with the longer cycle life of the high-power LIB (>104 compared with <1000 cycles for the high-energy density LIB and the lead acid battery), suggests the potential for lower “service” costs, or costs per cycle, of high-power LIBs with long cycle lives compared to other alternatives. High-power LIBs can also allow faster charging of EVs, thereby promoting greater adoption of consumer EVs.36,42

Although economically competitive, cost-per-cycle services will require the design and engineering of battery modules (from cells), and associated thermal and power management systems, rate performance, and cycle life are ultimately limited by the materials used in cells and the kinetics associated with the charge transfer reactions and ionic and electronic conduction. The requirement of long cycling life, which necessitates that parasitic side reactions are minimized, will be critical for the cost-effectiveness of LIB solutions for future flexible electrical power systems due to the need for rapid charging/discharging on a much more frequent basis than expected for most other LIB applications (e.g., EVs, residential storage, and portable electronics). This paper first reviews technological strategies that can be used to enhance the rate capability of LIBs; then subsequent sections discuss the projected costs of LIBs, the resource availability and recycling that would be required for high-volume manufacturing of LIBs to support high penetration levels of PV generation.

LIB technology

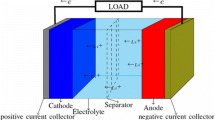

LIBs are based on the “rocking-chair” concept introduced by Armand and others in the 1970s36,43 The cell technology (see Fig. 2), which was first commercialized by Sony in the 1990s,34–36 comprises a graphite anode, a layered metal oxide intercalation cathode, and an electrolyte comprising a Li ion salt dissolved in organic liquid. Commercially produced LIBs can achieve volumetric energy densities exceeding 770 Wh/L,44 allowing for driving ranges of more than 500 km (Tesla Model S P100D, Tesla, Fremont, California). Power densities for these cells tend to be limited to <1 kW/L, but new high-power 21700-format cells may be able to push this toward 1.5+ kW/L.45 Limitations to charging/discharging rates can arise from anode and cathode materials, electrolyte selection, and fabrication process.

Schematic diagram of an intercalation Li ion rechargeable battery. Most commercially produced LIBs comprise a graphite anode, a metal oxide cathode (e.g., LCO, LMO, NCA, and NMC), and an organic electrolyte with a Li ion salt (from Dunn et al.37 and reprinted with permission from AAAS).

The low lithiation potential of graphite (~0.1 versus Li+/Li) results in the formation of a solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) at the graphite surface due to the reductive decomposition of electrolyte species at low potentials.46–48 The SEI electronically passivates the graphite anode but still allows the transport of Li ions to the electrode surface on charging; however, ionic transport is partially restricted by the SEI, which limits charging rates. The continued growth of the SEI during cycling, especially at high charging rates,49 limits the number of times the battery can be cycled. Additionally, at high rates, Li has a propensity to “plate” on the graphite electrode, resulting in Li dendrites that propagate through the separator and cause short circuits, leading to thermal runaway and fires.50–55 These limitations are exacerbated at high rates due to large Li-ion concentration overpotentials49,56,57 that can evolve as the ions diffuse along the tortuous pathways presented by the flake-like graphite particles of electrodes.58

There have been numerous developments since the 1990s in layered metal oxide intercalation cathode materials, especially with regard to increased capacity and/or voltage, both design attributes leading to increased energy density.59,60 Cathode materials used in commercially produced LIBs include LiCoO2 (LCO), LiMn2O4 (LMO), LiFePO4 (LFP), LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 (NCA), and LiNixMnyCo1-x-yO2 (NMC). Although typically LIB cathodes are not rate limiting, use of higher charging rates can result in significant reductions in capacity and increased battery impedance.55,61

Technological design strategies

The key advantage of LIBs for high-rate applications lies is the fast diffusion rates of Li in electrode materials combined with its low mass and high electronegativity, allowing for high gravimetric and volumetric energy and power densities.62 Although the rate capabilities of battery cells are best discussed in terms of the specific gravimetric and/or volumetric power and energy densities which take into account the mass/volume of all components of the entire cell, the rate capability of electrode materials is useful to report and consider in terms of capacity and cyclability at comparative C-rates or current densities with appropriate consideration for areal loading and active material content. The C-rate is the rate at which an electrode (or device) is discharged relative to its theoretical capacity [e.g., a 1C rate means that the (dis)charge current will fully (dis)charge an electrode or device in 1 h; 10C is 10 (dis)charges per hour or 6 min per complete (dis)charge]. The term “high-rate” is often used without a clear definition; however, for this article, we assume that it applies to batteries that can be operated with a C-rate exceeding 1C, which is consistent with the definition used by Eftekhari,63 and is a reasonable definition for large-scale applications, such as grid scale and EVs, though we acknowledge that high-rate is a relative term and a value of 5C–10C may be more appropriate for smaller battery cells in portable devices with more manageable strategies for heat generation.

Electrode materials

Since dendritic growth of Li on graphite anodes is enhanced at larger current densities,64,65 high-rate LIBs tend to use anode materials that can be cycled at higher potentials for increased safety. Crystalline materials on the binary Li2O–TiO2 composition line [e.g., the spinel form Li4Ti5O12 (LTO)66–68] have been used as an alternative anode material for high-rate LIBs due to their higher Li ion insertion potential of ~1.5 V versus Li+/Li.69–71 Although the higher reaction potential decreases the energy density of the battery and in doing so increases the cost per kilowatt hour stored, it diminishes the risk of Li plating and dendrite formation during cycling at high rates. Additionally, electrolyte decomposition is thermodynamically less favorable at the higher voltages. This minimizes SEI formation and reduces impedance on charging/discharging thus improving rate capability. The higher voltage also permits the use of the Al as a current collector (which is lighter and cheaper than Cu) as Li alloying with Al does not occur until 0.3 V versus Li+/Li.72

Spinel LTO has an excellent cycle life due to its thermal stability and negligible volume change on cycling.56,68,70 It was the first commercialized non-carbonaceous anode material for LIBs, with Toshiba and Altairnano employing anodes comprising micrometer-sized secondary LTO particles for higher rates and longer cycle lives in their higher rate LIB products, which have achieved power densities of 4 kW/kg (6.5 kW/L).73–76 However, the specific reversible capacity of LTO electrodes is limited to less than 175 mAh/g (Li4+xTi5O12, 0 ≤ x ≤ 3),70,77 with its charging/discharging rate being limited by the poor conductivity of the micrometer-sized particles used in the electrodes.67 In recent years, these issues have been addressed through use of C-coating and nanostructuring, allowing LTO capacities exceeding 150 mAh/g to be achieved at rates of 10C78,79; however, these strategies negatively impact the volumetric capacity and may not be commercially viable for some applications.

Various crystalline TiO2 polymorphs have also been explored as alternatives to LTO. Fully lithiated TiO2 (i.e., LiTiO2 corresponding to 100% reduction of Ti4+ to Ti3+ on lithiation) has a theoretical capacity of 335 mAh/g, which is only slightly less than that of graphite (372 mAh/g). Among the many crystalline TiO2 polymorphs reported, rutile, anatase, brookite, and the “bronze” form TiO2–B80 have been shown to have Li electrochemical activity, and all have theoretical volumetric capacities that significantly exceed that of LTO (see Table SI).70 However, full lithiation of these TiO2 polymorphs can only be approached using nanostructures,70,71,81,82 and it has been largely through the study of nanostructured TiO2 polymorphs that differences in Li ion charging/discharging rates and capacities arising from crystal structure have been observed. Of particular interest, has been the high rate and cycle life reported for the bronze polymorph TiO2–B.70,83–86 The faster charge storage reported for this form has been attributed to freely accessible parallel channels for Li ion transport perpendicular to the (010) face83 in the relatively open bronze polymorph.70

Another strategy for increasing the energy density of Ti-based anodes without significantly compromising their rate capability is to incorporate additional transition metals.87–93 Higher capacities are theoretically possible, especially if the valence of the added metal can change by more than one (e.g., through use of Mo, W, V, and Nb). The addition of heavier metals may not necessarily increase the specific energy density of the resulting cells;61 it is more likely to lead to gains in volumetric performance. Of particular interest has been the family of TiO2–Nb2O5 (TNO) materials due to their high theoretical capacity (up to 400 mAh/g with multielectron redox; see Table S1) arising from the idealized Ti4+/Ti3+ and Nb5+/Nb3+ redox couples.87,88,92–94 Toshiba have adopted this strategy in their high-power SciB cells, which employ a TiNb2O7 anode comprising C-coated micrometer-sized particles and an LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2 (NCM) cathode to achieve power and energy densities of 10 kW/L (charging for 10 s at 50% state of charge) and ~350 Wh/L, respectively.93 Although this energy density surpasses that of similar cells with LTO anodes (177 Wh/L),40 it is still only half that possible with state-of-the-art high-energy density cells.

This approach of using open structural motifs can present advantages over nanostructuring in achieving higher rate electrodes without compromising capacity because volumetric energy density is not reduced due to pore volume (i.e., they have greater tap density). Griffith et al. adopted this approach with NbxWrOz 3D open lattice structures. The multielectron redox capabilities of both Nb5+ and W6+ lead to theoretical capacities for NbxWyOz compounds of 300–400 mAh/g (similar to the titanium niobium oxides); however it remains open as to whether full two electron redox will be accessible under stable cycling conditions (especially at high rates) even though multielectron is achievable in both individual metal oxide families. With electrodes comprising Nb18W16O93 micrometer-sized solid particles, capacities of ~150 mAh/g at 10C and ~75 mAh/g at 100C were realized (see Fig. 3).95 Nanostructuring or the use of amorphous forms of mixed metal oxides96 may provide paths to further increases in (gravimetric) capacity for these multiple transition metal anode materials.

Structure of the bronze-like Nb18W16O93. (a) Crystallographic structure of the bronze-like Nb18W16O93 showing open the structural motif that facilitates fast Li ion diffusion through the lattice, (b) electrochemical voltage profiles as a function of lithium concentration and C-rate, (c) derivative curve of the voltage profiles, (d) electron microscope image showing the micrometer-sized particles of the mixed metal oxide, and (e) gravimetric capacity as a function of C-rate for two different NbxWy0z materials and cycling limits (reproduced with permission from Griffith et al.95).

Although this discussion has focused more on anode materials due to the need to find alternative safe anode materials for high-rate devices, achievement of high rate in cells requires that the Li insertion and extraction processes and electron transport are rapid in both the anode and cathode materials. Currently, most cathode materials are limited by the conduction of Li ions in the crystalline cathode material. Consequently, large concentration overpotentials occur at high lithiation rates, resulting in electrolyte oxidation, dissolution of cathode materials, and corrosion of the current collector.50,97 Metals released by cathode oxidative decomposition can diffuse through the electrolyte to deposit on the anode and/or contribute to SEI growth and further degrade battery performance.55,61 Collectively, these aging mechanisms result in increased impedance and reduced cycle life of the battery and may necessitate a narrowed cycling voltage (thus smaller utilized capacity) to be used for high-rate operation. The material strategies that have been discussed above could also be applied to the engineering of high-rate cathode materials, although additional research is required to understand the electrode degradation mechanisms with high rate usage at high oxidation potentials.

The rate capability of both anode and cathode materials can also be enhanced through the use of carbon coating and nanosizing. An often-quoted example of the value of carbon coating is the story of FePO4, a material that was initially considered to be a low-rate cathode material due the poor electronic conductivity of both oxidized and reduced forms and poor ionic conductivity of micron-size particles.98,99 The use of nanomaterials decreases both the Li and electron transport lengths. Additionally it reduces the probability that Fe antisite defects block ion transport in the 1D tunnels (aligned in the [010] crystallographic direction). It was found that the rate of charging/discharging these electrodes was also dependent on the Li ion transport across the surface of the particles as the ions can only move into the bulk of the crystalline FePO4 in 1D channels.99–101 By carbon coating the surfaces of the particles, charging capacity was significantly increased.102,103 Herle et al. proposed that the increased rate capability was due to the formation of a highly conductive surface layer of iron phosphide (FeP) arising from the carbothermal reduction of Fe at C-contaminated FePO4surfaces.104 Kang and Ceder reported the fabrication of a conductive Li4P2O7-like amorphous phase on the surface of the particles using a heat treatment to improve the rate capability of LFP cathodes. With this process, they were able to achieve electrode capacities of >100 mAh/g at 200C and 60 mAh/g at 400C, although using an electrode with a very dilute concentration of active material.99 In view of these remarkable results, they concluded that electrode materials with extremely high-rate capability will “blur the distinction between supercapacitors and batteries,”99 a point that we will return to later in this article. More recent work has shown that the high rates achieved in LFP are associated with the ability of the material to operate via a metastable LixFePO4 solution during high-rate cycling; the classical model of intercalation in material that operates via a two-phase reaction, involving nucleation, growth, and movement of a phase boundary is no longer appropriate, at least at high rates.105–108

Electrode morphology and structuring

Micro- and nanostructuring of electrode particles can be used to achieve higher capacity and rate capability in LIBs.109,110 In particular, it can (i) increase the electrode/electrolyte interface area thereby enabling increased charge storage; (ii) provide shorter path lengths for both electron and Li ion diffusion that can improve high-rate performance; and (iii) more readily accommodate the strain associated with Li insertion/removal, which can enable increased cycle life. However, set against these advantages are some disadvantages, which include (i) increased undesirable electrode/electrolyte reactions due to higher surface area leading to higher impedance, reduced rate, and diminished cycle life; (ii) less-dense packing of active material (i.e., lower “tap density”), leading to lower volumetric energy densities; and (iii) potentially more complex and/or costly electrode synthesis, which preclude use in large-scale battery manufacturing.109 When optimizing electrode materials specifically for high-rate performance, the contribution of micro- and nanostructuring to the kinetics of charge storage can be complicated by how the porosity is introduced in the electrode. For electrode materials in which electronic conductivity and charge transfer reactions are not rate limiting, ion transport in the host materials and/or the percolating electrolyte of 3D porous materials can become limiting.111

Numerous approaches have been proposed to structure electrode materials at the microscale to increase electrolyte access. These include laser structuring,112,113 hard templating (e.g., colloidal crystal),114–116 and soft templating114,117; however, it is necessary to establish the C-rates over which the structuring or templating process effectively increases capacity or capacity retention with high rates.112 If the Liion concentration becomes depleted at surfaces due to fast cycling, this can result in large concentration overpotentials, which limit the rate of the charge transfer reactions.112 At high charging/discharging rates, highly tortuous Li ion diffusion paths can restrict access to some regions of the current collecting surface, which can significantly curtail the capacity.118 One approach by which high capacity can be retained with high-rate cycling is to use a dual-scale porosity, which combines channels, coated with a porous matrix, aligned to be perpendicular to the current collector.111 This arrangement can facilitate Li ion access to a 3D volume without depletion of ions at the electrode surface. It can also allow for thicker electrodes to be used for increased capacity.118 It is important that both electrodes in a device can support high charging and discharging rates. For example, although laser structuring of a graphite anode can increase capacity over the range of 1-3C, at faster rates, the device performance can become limited by the cathode.112

Nanoscale structuring, through formation of nanoparticles, nanotubes, nanofibers, and nanowires, can also be used to increase Li ion flux at surfaces.109,119-127 Additional benefits can arise from (i) space charge effects at the electrode/electrolyte interfaces and (ii) spatial confinement, both factors having the potential to change the thermodynamics of charge transfer reactions from that observed in bulk materials.109,125,128,129 Nanoconfinement (see Fig. 4) can impact ion transport in the electrolyte, phase transitions, and solvation structures.125,130-132 It has been shown to enhance charge storage in electrochemical capacitors, which have emerged as high-rate complementary energy storage solutions to batteries.133–135

Nanoconfinement of a hydrated ion in a 3D carbon nanopore. Schematics showing (a) a low level (i.e., retention of some hydration) and (b) a higher level of nanoconfinement. The light blue, red and dark blue circles represent the bare ion, the hydrated ion, and the cutoff radius for which the degree of confinement is determined, respectively. In this model, the ions are assumed to be hard spheres that can approach the electrode surface as close as their bare ion radius (reproduced with permission from Prehal et al.135).

Hierarchical micro-nanostructured electrodes can exploit the positive attributes of nanostructures for increased surface area, nanometer diffusion lengths, nano-confinement effects, and microstructures for improved stability and ease of handling during electrode preparation.119,136 They can be fabricated through the aggregation of nanosized crystallites to form larger, porous agglomerates, which can be then further grouped into micrometer-sized grains (e.g., see Fig. 5).79 The resulting multiscale porosity can enable effective penetration of the electrolyte, with the distance for Li ion diffusion lengths being minimized within the electrochemically active nanoparticles. The application of this hierarchical structuring process using LTO nanoparticles enabled the achievement of a capacity of 170 mAh/g at 50C with minimal capacity fading after 1000 cycles.79 The higher capacities observed in the hierarchically structured electrode in comparison with bulk LTO were partially attributed to the formation of a Ti-rich surface layer.79,137 This highlights that nanostructuring may also introduce benefits in terms of metal-oxide surface stoichiometry138 in addition to improved electrolyte access and greater accommodation of strain. Understanding the surface atomic structure is also critical to the understanding of electrolyte decomposition side reactions that result in gas generation and SEI formation.138

Hierarchical micro-nanostructure through aggregation. Schematic depicting the hierarchical aggregation of crystalline nanoparticles into the progressively larger microparticles used for electrode fabrication (adapted from Odziomek et al.79 and reproduced under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License).

Another common approach to fabricating hierarchical micro-nanostructures is to coat 3D microstructured current collectors (e.g., metal foams), which provide a percolating network for both electron and ion pathways with an electroactive nanoma- terial.136 Coating can be achieved by thermal oxidation,139,140 electrodeposition,141 casting of a slurry,136,142,143 or surface anodization.144,145 With processes where the active material is directly grown on the metal scaffold, the need for binder can be eliminated. Typical fluoropolymer binders are insulating and electrochemically inactive; they decrease gravimetric energy density and increase the resistive losses and hence power losses, especially under high-rate operating conditions. Binder material can also swell in commonly used organic electrolytes, leading to poor stability and irreversible capacity losses.146,147 Anodization of metal foams in fluoride-containing electrolytes to form nanotube arrays on the foam surface is one approach that has been successfully used to fabricate hierarchically structured electrodes.144,145 Figure 6 depicts the growth of TiO2–x nanotubes directly on a Ti foam current collector. The foam allows increased Li ion access to the surface structures and the 20-50 nm thickness of the TiO2_x nanotube walls improves electronic conductivity of the electrode.145

Hierarchically structured TiO2_x anode formed by anodization of a Ti foam current collector. (a) and (d) Low- and high-magnification images of the Ti foam, (b) scanning electron microscope image of amorphous TiO2–x nanotubes formed on the foam surface, and (c) distribution of pore sizes as determined by X-ray computed tomography. Galvanostatic charge/discharge curves are shown in (e) and (f) for amorphous and crystalline TiO2-x nanotube arrays on Ti foams, respectively (adapted from Jiang et al.145).

A key practical concern for all structuring methods is whether a process can be practically scaled to manufacturing and whether the improvements in rate or cycle life that can be achieved result in a commercial advantage. Nanostructuring generally reduces tap density and so it is necessary to consider volumetric as well as gravimetric energy and power densities.95,148 Also, although the larger surface area introduced by nano/micro-structuring can be beneficial for high-rate performance, it can increase the probability of undesirable side reactions and consequently reduce cycle life. To minimize this possibility, as is the case for supercapacitors, highly pure materials will be required and this can increase battery cost.

Electrolyte selection

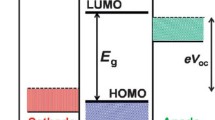

The rate and cycle life of LIBs depend strongly on the electrolyte used.149 Most currently produced LIBs utilize electrolytes comprising Li ion salts (e.g., 1.0 M LiPF6) in a mixture of organic solvents. Common solvents used include ethylene carbonate (EC), dimethyl carbonate (DMC), diethyl carbonate, propylene carbonate (PC), and ethyl methyl carbonate.62’150 Organic solvents permit a voltage operating window that is approximately three times larger than that possible with equivalent salt concentrations in aqueous electrolytes due to their greater oxidative and reductive stability compared with water. This wider voltage window results in LIBs having enhanced gravimetric and volumetric energy densities compared with batteries that use aqueous electrolytes. However, the ionic conductivities of the organic electrolytes are lower (e.g., 1–12 mS/cm for 1.0 M LiPF6 in EC/DMC62,151) than those of aqueous electrolytes [(e.g., 600–825 mS/cm for ~1.2 g/cm3 H2SO4 (aq.) used in lead acid batteries152]. To help compensate for the low conductivity of the electrolyte, high-rate Li-ion cells typically use thin electrode stacks (e.g., <100 µm thick).118

One rate-limiting property of the organic electrolytes is their low Li+ transference number, t+, of <0.5.153,154 This means that the ionic current is carried predominantly by the counter ion and not the Li+ on charging and discharging. The low transference number arises from the preferential solvation of Li+ compared with its counter ion in carbonate solvents and results in a concentration gradient that limits the rate at which the battery may be charged or discharged. It also limits the charging voltage, and hence energy density of the battery, through an increased concentration overpotential and this, in turn, places an upper limit to the thickness of the electrodes used. Doyle et al. showed (by simulation) the importance of using an electrolyte with a high t+ for high-power batteries and demonstrated significant enhancement in terms of rate capability when using a t+ = 1.0 Li ion polymer electrolyte over an electrolyte with t+ ≈ 0.2 even with an order-of-magnitude decrease in electrolyte conductivity in the former.153 Improvements in energy density were especially evident at high charging/discharging rates when Li ions became depleted with low t+ electrolyte due to their slower transport to the electrode surface.

One approach to increasing the Li ion transference number in organic electrolytes is to use larger and hence lower mobility polymeric anions.155 Design of such electrolytes requires maximizing both the free Li ion concentration and localized charge density of the anion groups on the polymer backbone, while keeping the polymer content as low as possible so as to not overly increase the electrolyte viscosity.155 However, to-date, very few attempts at improving ion conductivity have been realized through this approach because the choice of anions suitable for Li ion electrolytes is limited62 and anion suitability also depends on their electrochemical stability at electrode surfaces. Instead, solvent composition tailoring has been the main tool for manipulating electrolyte ion conductivity due to the availability of a vast number of candidate solvents. For solvated Li ions to migrate quickly under an electric field, ideally the solvent molecules prevent the Li cations and the electrolyte anions from forming close ion pairs. Solvents with a higher dielectric constant screen ion interactions; however, these solvents typically have a higher viscosity, which acts to slow ion movement in an electric field. Consequently, solvent mixtures are used, with one component selected for ion shielding (i.e., high dielectric constant) and the other(s) selected for their low viscosity.62

As mentioned in the earlier discussion of LIB Technology, an SEI typically forms at LIB anode surfaces due to reduction reactions involving the chemical species in the electrolyte. Migration of ions through this surface layer is typically the rate-limiting step for most LIB chemistries.46,47,62 An analogous layer called the cathode–electrolyte interface (CEI) forms on cathodes by oxidation reactions involving electrolyte components at high potentials but the impact of this thin or possibly transient layer on battery cell performance is generally considered to be less significant.50,97 The nature of the formed SEI depends on many factors, including the anode material and electrolyte composition. When the SEI continues to grow on cycling, it increases the cell impedance and eventually consumes the finite quantity of Li, limiting the cycling life of the battery. Consequently, some control over SEI formation and growth is critical for the achievement of LIBs with high rate capability and cycle life. One option is to use electrode materials with a higher (i.e., less negative) reduction potential (e.g., those based on early transition metals, as discussed previously for electrode materials), so that the parasitic reactions and hence SEI formation can be minimized; however, the increased rate and cyclability are achieved at the cost of capacity due to the significantly reduced lower cell voltage. Furthermore, the less-passivated surfaces of the high potential anodes can give rise to challenges, such as gas generation and pressure buildup in the cell.156–158

Another option is to engineer an artificial SEI to achieve high and stable conduction of Li ions to the electrode surface.48 The SEI composition can be tuned by using additives in the electrolyte that will react at the surface before the electrolyte solvent and anion species.47 Another option is to carefully select the choice of solvent as some solvent species have been shown to form more stable insulating layers without seriously impacting the Li ion conduction. Takenaka et al. confirmed, using atomistic simulations (see Fig. 7), that an EC-based SEI film can prevent excess reduction of electrolyte on a graphite anode surface while still allowing Li ions to pass through. In contrast, a PC-based film could not sufficiently insulate the anode surface, allowing continued electrolyte reaction despite PC only differing from EC molecules by the presence of their methyl side groups.159 This example highlights the need for a greater understanding of SEI formation and, in particular, use of simulations to guide the development of electrolytes for stable SEI layers with high conductivity for high-rate LIBs.47,48,159

Atomistic models of SEI films formed over a graphite anode. Models showing (a) an EC-based electrolyte, and (b) a PC-based electrolyte (green = SEI film; blue = Li+; gray = PF3, C2H4, or C3H6; purple = EC or PC; orange = PF6) (reproduced with permission from Takenaka et al.159).

Another electrolyte strategy that may offer a path toward longer cycle life and perhaps also higher rate is to use superconcentrated, or high ion-to-solvent ratio, electrolytes.160–162 Although lowering ionic conductivity,160 this newer class of electrolyte has been proposed to provide greater oxidative stability (allowing higher cycling voltages and commensurately larger energy densities), reduced volatility and flammability, and enhanced Li ion interfacial transport.161 A key reason for the continued use of the 1.0 M LiPF6 electrolyte in commercially produced LIBs has been the ability for this salt to protect against the corrosion of the Al current collectors by forming an AlF3 coating on the cathode through the reaction of hydrogen fluoride (HF, a breakdown product of PF6–)163 with Al.61,164 However, HF also acts to dissolve the metal oxide cathode material,165 releasing metal ions, which can subsequently deposit on the anode where they further catalyze the reduction of electrolyte solvent.166,167 This degradation process consumes Li ions and thickens the SEI for graphite anodes and, in doing so, decreases both the rate capability and cycle life of the battery.

Wang et al. have demonstrated the use of the more stable LiN(SO2F)2 (LiFSA) salt mixed with DMC at very high salt: solvent molar ratios of 1:1.1 (compared with 1:10.6 for the 1.0 M LiPF6 in EC/DMC) to achieve cathode stabilities at potentials of up to 5 V versus Li+/Li, promising long cycle life and high rate capability with enhanced safety. This superconcentrated electrolyte forms a 3D network of anions and solvent molecules that coordinates the Li ions and effectively inhibits the dissolution of both the Al cathode current collector as well as the transition metal oxides at potentials of up to 5 V.160 In electrolytes with salt-to-solvent molar ratios of >1:2, the solvent molecules are mostly coordinated by Li ions in the primary solvation shell, and this decreases the reactivity of the solvents molecules at the electrolyte surfaces.162 Although some sacrifice in electrolyte conductivity results with high salt-to-solvent electrolytes (~1.1 mS/cm for LiFSA at 30 °C with 1:1.1 molar ratio)160 compared with ~6 mS/cm (1:10.6 molar ratio) for 1.0 M LiPF6 in EC/DMC,151 the improvement in cycle life that may result from the diminished reactivity at electrode surfaces may be valuable for services, such as grid stabilization, depending on the cost of the salt.

Strategies considered together

Typically, any high-rate LIB device design will draw upon more than one of the aforementioned design strategies; however, there are also interdependencies. For example, changes in electrolyte to optimize SEI formation need to take into account the materials used for the electrode. If an anode comprising an early transition metal is adopted, specifically for increased cycle life, then additives or specific solvent combinations to enhance the formation of an ion conductive SEI may not be required as the higher voltage minimizes reactions involving electrolyte species. Similarly, if electrode structuring is used, consideration should be directed at how a structured electrode volume with different diffusion length scales impacts the electronic and ionic conductivity of the electrode and even SEI formation. Identifying the rate-limiting steps and processes on charging and discharging both the anode and cathode becomes the key to optimizing battery cells for improved rate and cycle life.

This independency of strategies highlights the importance of improving our understanding of all mechanistic aspects of LIBs if we are to effectively engineer storage devices capable of high rates and very long cycle lives at costs that are competitive for grid stabilization services. The above discussion of SEI formation highlights the importance of simulation and modeling in this next phase of LIB design and evolution. The electrochemical reactions involved in these cells are complex, and greater understanding of the rate-limiting steps in fast charge transfer reactions is required. For many years, it has been assumed that Li ion diffusion limits charging/discharging rates168; however, recent reports are now suggesting that the charge transfer kinetics may also become limiting in cases where Li ion diffusion may be rapid.145,169 This suggests that more advanced simulation models may be required to predict ionic and electronic flow though percolating porous networks and rates of charge transfer reactions.169,170

Integration into systems

A possibly advantageous attribute of high-rate LIB electrodes is that the linearly responsive capacitive-shaped (potential versus charge) discharge curves typically observed with fast electrode reactions can enable energy storage control systems to more reliably determine the state-of-charge (SoC) of the battery. Figure 8(a) shows discharge curves for a TNO/NCM LIB (1C capacity = 49 Ah) at different C-rates. Unlike typical flat battery discharge profiles, for the range of rates shown, it is possible to determine the SoC of the battery due to the constantly declining voltage with discharge. Knowledge of the SoC during charging and discharging can reduce the complexity of integrating energy storage functionality in power electronics and facilitate more flexible grid stabilization systems that maintain the LIB in an optimal SoC by rapid-response charging from the grid when demand for electricity is low. We note, however, that too large variations in voltage require additional circuitry to manage. Integration of energy storage SoC into optimization algorithms for ramp rate control31,32 and frequency stabilization29,33 may provide a way to increase the battery lifetime by decreasing the frequency and duration of deep discharges or charges, which tend to degrade LIBs.50 If the cost of LIBs can be decreased significantly (see later discussion), then it may become possible to integrate compact storage elements within smart junction boxes of PV modules (e.g., in DC–DC power optimizers or microinverters) to limit the ramp rate of generated power in the presence of intermittent insolation [see Figs. 8(b) and 8(c)].22 This can contribute to the smoothing of high-frequency power changes when exporting power to the grid.

Capacitive-shaped discharge curves of high-rate LIBs allowing the SOC to be beneficially used when integrating energy storage with power electronics. (a) Capacitive-shaped discharge curves for a high density TNO/NCM LIB at different C-rates at 25 °C (reproduced with permission from Takami et al.93), (b) configuration of a PV system with an energy storage system (ESS) integrated in the PV module junction box for ramp rate control, and (c) compliance (%) for a range of different ESS technologies to achieve a power ramp rate of 10% per min power assuming that the ESS in (b) has a maximum volume of 0.1 L (adapted with permission from Jiang et al.22).

The linearly responsive capacitive-shaped discharge curves and the higher discharge rates that can be achieved with high-rate LIBs present an opportunity for high-rate LIBs to replace higher cost electrochemical capacitors in industrial applications.95,99 Kang and Ceder reported the ability for LIB electrode materials to support volumetric power densities of ~65 kW/L (~25 kW/L at a battery level),99 which exceeds that of a Maxwell BCAP3000 P270 supercapacitor (~7.5 kW/L, Maxwell Technologies, San Diego, California).171 Provided that such high-rate LIB materials can also approach the long cycle lives of supercapacitors, they may find applications in regenerative breaking, emergency power supplies, and heavy transport.172 Their increased energy density compared with carbon-based supercapacitors may also enable new solar-powered applications, which use embedded localized power sources. Examples include solar-powered tools and devices for remote areas and compact integrated solar- powered devices for space operation (e.g., energy buffers for solar-powered antennae for CubeSats).173

Cost considerations

Schmidt et al. recently reported product energy and power price manufacturing experience curves for four categories of Li ion technology: (i) electronic (C ~ 1); (ii) EV (C > 1); (iii) residential (C ~ 1); and (iv) utility (C ~ 1).174 Of these categories, the product power price of EV LIB packs were lowest [<US2015$100/kW (capacity)], with an experience rate of 16%. From the indicative C rates for each category, it is assumed that the residential and utility categories are focused more on “energy” or capacity applications (e.g., load shifting) and that the higher power EV category is perhaps the best indicator of manufacturing experience for high-rate LIBs that could be used for grid stabilization applications. EV LIBs are expected to approach material costs (currently estimated at <US$100/kWh) and so it is reasonable to expect that product costs of electrochemical storage for electrical grid stabilization could approach similar values.174

However, what is critical for grid stabilization is the “service cost” of providing power stabilization. If alternative options for frequency stabilization are costly, then higher energy storage system costs may be tolerated for this application than for EVs and longer term storage.36 Service costing is further complicated by the fact that the expected cycle life of LIBs performing high-rate charging/discharging for grid stabilization may differ from that when the same battery technology is used for other applications. For example, as mentioned above, if control systems implement strategies, which maintain the SoC at an optimal state, then deep cycling may be minimized, thereby prolonging the battery life over use cases where batteries are fully dis- charged/recharged.

In Lazard’s 2016 analysis of cost of storage,175 LIBs were assessed to be the most cost-effective technology for frequency regulation (lower end electricity cost of US$159/MWh) and one of the cheaper options for peaker replacement (lower end electricity cost of US$285/MWh). In 2017, Lazard revised their reporting structure to consider (i) in front of the meter use cases (microgrid, peaker replacement, and distribution) and (ii) behind the meter use cases (residential and commercial).176 They viewed frequency regulation as a service that could be provided by each of peaker replacement, microgrid, and commercial (behind the meter) use cases and concluded that LIBs are the only energy storage technology that can span this operational range with a cost-competitive service. Further reduction in costs from manufacturing experience and increased cycle life is expected to increase this advantage even further.

Resource availability

An often-cited concern for large-scale adoption of LIBs for portable electronics, EVs, and renewable energy integration is the availability of Li. Lithium is the 25th most abundant element in the earth’s crust and it is found all over the world, including in the oceans.177 However, extraction of Li requires both favorable environmental surroundings and scientific expertise. Most Li production, typically in the form of Li2CO3 or LiOH,178 comes from Australia, Chile, Argentina, and China. It is extracted from continental brines in salt lakes, pegmatite minerals, such as spodumene (LiAlSi2O6) and petalite (LiAlSi4O10), or clays.177,179,180 Global economically extractable reserves are heavily concentrated in these four countries, but additional resources exist in Bolivia, United States, Canada, Congo, Russia, and Serbia, with smaller reserves and production in Portugal, Brazil, and Zimbabwe.179,180 Driven by the growth in manufacturing of LIBs, global Li production has increased by about 20% per annum since 2000,178 and in 2017, the LIB market accounted for about 50% of the 43,000 metric tons of Li consumed.180 The economically recoverable global Li reserves are estimated to be 16 million tons, with total resources of 53 million tons being estimated by the 2018 U.S. Geological Survey analysis.180 Figures for available reserves are constantly changing and the fraction of total resources that are economically extractable depends on the maturity of extraction technology177,181–183 and value of the commodity, the latter having more than tripled in the last five years for Li.184

Recent analysis suggests that total demand for Li could increase to 80,000 tons per annum by 2030,179 and consequently, a number of new Li mining projects are already underway.178 Lithium is also extensively used in glasses and ceramics (applications that are also predicted to increase in the future); however, availability of Li is not expected to significantly impact LIB production in the next 20 years. Narins suggests that the world could triple its 2016 production and still have enough Li for 135 years solely from currently known reserves and not considering new sources of Li that are being investigated.185 Despite these abundant reserves, Li2CO3 prices rose from approximately US$5,000 per metric ton in 2010178 to US$15,000– 24,000 per ton early in 2018.180 This increase was due to a supply–demand imbalance,178 and the correction of this imbalance is already being observed as prices are falling. Morgan Stanley are predicting a 45% cost reduction by 2021 due to production exceeding demand,186 though there is some concern that the required ramp-up in production may not be fast enough to meet demand.187,188

Greater concern should arguably be directed at other metals that are required by LIBs and, in particular, Cu and Co. Due to its thermal and electrical conductivity and its resistance to corrosion, Cuis a major industrial metal, ranking third after Fe and Al, in terms of quantities consumed. The electronics industry is the largest consumer of Cu and accounted for 39% of global demand in 2015.189 Copper is required for electrical connectors and cables, a demand that is expected to increase with growing adoption of LIBs to support transport electrification and renewable energy integration. Each EV requires four times as much Cu as its gasoline counterpart, and this comparison does not include the Cu used for recharging infrastructure and electricity generation.185 In addition, renewable energy generation is estimated to require 11–40 times as much Cu as conventional fossil fuel-based power generation.190,191 In an assessment of the resources required to support future large-scale implementation of solar PV, wind, and concentrated solar thermal power, Hertwich et al. concluded that Cu was the only material for which supply may be a concern.190 Copper is currently one of the most recycled metals192; however, the projected future demand suggests that improved recycling processes may be required as the average recycled content remains below 50%.192,193

In 2017, 48,000 metric tons of Co was consumed by the battery industry (from a total world production of 110,000–117,000 metric tons194,195) and this usage is expected to increase to 127,000 metric tons by 2025 based on estimates of LIB production for transport electrification.195,196 As for Li, Co is not extraordinary rare, but it is difficult to extract in purities high enough to justify production, and so currently, most Co is extracted as a by-product of Cu and Ni mining. Additionally, unlike the reasonable geographical diversity of Li resources, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) extracted more than 50% of the world’s Co in 2017.188,196,197 Added to concerns about the political stability of the DRC, China is dominant in Co refining188,198 and relies on the DRC for over 90% of its Co supply.197 These supply chain factors make for a risky situation for LIB producers, and this situation may be reflected in the Co price rapidly increasing from ~US$30,000 per metric ton in 2014 to over US$80,000 in 20 17.196 From the long-term perspective of global economic reserves or total resources, there is only about half as much Co as Li and a LiCoO2 LIB requires several times more Co than Li by mass. In consideration of these factors, a global shift is occurring in the research and commercial battery communities toward less Co-intensive cathode materials, such as NCA (LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2) and Ni-rich NMC (LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2), however there are already concerns about the long-term sustainability of Ni. One advantage that high-rate LIBs may leverage is that they can make use of the less resource-constrained LiFePO4 cathode materials, as energy density may not be such a premium for grid stabilization functionality. Additionally, by using higher voltage anode materials, Al can substitute for Cu as the anode current collecting metal, which decreases the total electrode cost and mass and eases the demand on Cu resources.

Recycling

Lead-acid batteries are extensively recycled due to the toxicity of Pb, the relatively simple recycling process, and government regulations. In the United States, they are managed as Universal Waste and must be recycled.199 However, similar recycling regulations do not exist for LIBs, and currently, most LIBs are landfilled as recycling has not been proven to be economically viable at scale.184 Recycling of LIBs is complex because of the mix of materials used in the batteries. If spent LIBs are burned as a general type of solid waste, they will produce hazardous gases, such as HF due to the fluorinated electrolyte.200 In addition, Li is extremely reactive with water, making fire a risk for both landfilling and also recycling. Recycling of LIRs typically involves pyrometallurgical (smelting) and/or hydro- metallurgical (chemical separation) processes.184,201,202 Pyrometallurgical methods are usually limited to recovering Co, Ni, and Cu; however Al, Mn, and Li are lost in the slag.184 Additionally, these processes require a large amount of energy with 5000 MJ of heat being required per metric ton of battery treatment (for smelter and gas cleanup).184 Hydrometallurgical processes can comprise many different chemical treatments (e.g., precipitation, solvent extraction, ion exchange, and electrowinning).184,203 Typically, they have a lower energy budget and also allow the recovery of Al and Li, but they require batteries to be mechanically crushed before treatment and can generate a large volume of process effluent that must be disposed of or recycled.184 Most industrialized LIB recycling processes can only recover secondary raw materials, which are not suitable for direct reuse in new batteries.204 Direct recycling, where battery materials (e.g., electrodes) are recovered and reintroduced into the manufacturing process with little additional processing methods, has been demonstrated at laboratory scale. This approach, which often employs supercritical CO2 to first remove the flammable electrolyte, can recover most battery materials.184

In 2016, almost 95% of the spent batteries from consumer electronics products were landfilled.204 To add to this disposal load, in 2018 end-of-life LIBs from EVs are expected to start contributing to landfill. China alone will produce 2.5 billion used LIBs with a mass of about 500,000 metric tons by 2020.200 Although disposing of LIRs in landfill can result in heavy metals and toxic electrolytes leaching into the groundwater202 and fires,204 to date, there has been limited environmental regulation and support from governments for collecting, sorting, and recycling spent LIBs.184 This situation is compounded by the fact that there is a large uncertainty regarding the cost of LIB recycling and hence the economic viability. If the cost of raw materials is less than the economically viable price for recycled materials, then there remains little incentive to recycle. To add to this situation, there is also uncertainty about the material composition of future LIBs. For example, if current efforts to reduce Co usage in batteries are successful, then the economic viability of recycling processes may be reduced even further.204 This uncertainty discourages development of highly specialized processes as they may become obsolete with material changes.

A number of recent reviews conclude that a regulatory driver may be necessary to develop and maintain a viable LIB recycling industry.184,205,206 Of particular concern is the treatment of spent LIBs, so that they are less hazardous to the environment. Current recycling processes, both pyrometallurgical and hydro- metallurgical, can introduce additional environmental concerns (e.g., contaminated wastewater, gas effluent), and so further research is required to develop alternative recycling processes that do not introduce secondary pollution.202 Recycling could be especially beneficial to LIB manufacturers that lack an economic raw material supply. So, for example, to become a major LIB manufacturer, the United States may need to build new supply chain capabilities around recycled materials.184

Conclusions and future perspectives

High-rate LIBs can play a critical role in decarbonizing our energy systems both through their underpinning of the transition to use renewable energy resources and electrification of transport. In particular, they can play a key role in future flexible and resilient low-carbon electricity networks. PV is the fastest growing renewable energy technology, growing 40% per year over the last decade and having the fastest manufacturing experience rate of all renewable energy technologies. Because demand and generation are constantly varying with a high fraction of PV generators connected to the electricity grid, fast-reacting energy storage systems can be used to inject and withdraw power to stabilize electricity supply. The energy-power balance of currentgeneration LIBs suggests their suitability for this application; however, emerging material systems that can respond rapidly and have a long cycle life will be required for future grid-stabilization services to be provided at low cost.

Although high-rate LIBs require the design and engineering of battery modules and associated thermal and power management systems, rate performance and cycle life are ultimately limited by the materials used in cells and the kinetics associated with the charge transfer reactions and ionic and electronic transport. This review has summarized the technological strategies that can be used to enhance the rate capability of LIBs and, in particular, we reviewed the electrode and electrolyte material selection, electrode morphology, or structuring for enhanced electrolyte access to electrochemically active surfaces and electrode fabrication processes. Recent reports of high-rate electrodes are highlighting the need for advanced simulation models to predict ionic and electronic conduction though percolating materials and rates of charge transfer reactions to identify and address rate-limiting processes.

The linearly responsive capacitor-shaped discharge curves of new materials combined with high-rate charging and discharging can simplify integration with power electronics as the SoC is more easily determined. This is particularly relevant for integration with PV-generated power and may enable embedded distributed storage elements in electronic control systems. Finally, reduced battery cost will be critical for competitively priced PV-generated electricity. Manufacturing of high-rate LIBs for grid stabilization can directly build on the EV manufacturing experience for LIBs, and so costs are expected to approach material cost limits, which have been estimated to be in the order of US$100/kWh. However, what is critical for grid stabilization is the service cost, and if alternative options for this service come at a high cost, then higher LIB costs may be tolerated here than for other battery applications. Recent reports suggest that LIBs are the only currently available energy storage technology able to provide support for the peaker, microgrid, and commercial (behind the meter) use cases, and this already competitive position can only be improved by LIBs with increased rate performance and perhaps more importantly increased cycle life.

Change history

01 July 2020

An Erratum to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1557/mre.2020.15

References

Edison T.: Storage Batteries (New York, 1883). Available at: https://archive.org/stream/pacruralpres25unse/pacruralpres25unse_djvu.txt (accessed October 22, 2018).

Tsao J.Y., Schubert E.F., Fouquet R., and Lave M.: The electrification of energy: Long-term trends and opportunities. MRS Energy Sustain. 5, E7 (2018).

Michalek J.J., Chester M., Jaramillo P., Samaras C., Shiau C.-S.N., and Lave L.B.: Valuation of plug-in vehicle life-cycle air emissions and oil displacement benefits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108(40), 16554–16558 (2011).

Traut E., Hendrickson C., Klampfl E., Liu Y., and Michalek J.J.: Optimal design and allocation of electrified vehicles and dedicated charging infrastructure for minimum life cycle greenhouse gas emissions and cost. Energy Policy 51, 524–534 (2012).

IRENA: Electricity Storage and Renewables: Costs and Markets to (2030). Available at: http://www.irena.org (accessed July 1, 2018).

IRENA: Renewable Energy Statistics. Available at: http://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2018/Jul/IRENA_Renewable_Energy_Statistics_2018.pdf (accessed March 8, 2019).

Creutzig F., Agoston P., Goldschmidt J.C., Luderer G., Nemet G., and Pietzcker R.C.: The underestimated potential of solar energy to mitigate climate change. Nat. Energy 2, 17140 (2017).

ITRPV: International Technology Roadmap for Photovoltaic Results (2017). Available at: http://www.itrpv.net/Reports/Downloads/ (accessed October 6, 2018).

Jacobson M.Z., Delucchi M.A., Bazouin G., Bauer Z.A.F., Heavey C.C., Fisher E., Morris S.B., Piekutowski D.J.Y., Vencill T.A., and Yeskoo T.W.: 100% clean and renewable wind, water, and sunlight all-sector energy roadmaps for 139 countries of the world. Joule 1(1), 108–121 (2017).

Clack C.T.M., Qvist S.A., Apt J., Bazilian M., Brandt A.R., Caldeira K., Davis S.J., Diakov V., Handschy M.A., Hines P.D.H., Jaramillo P., Kammen D.M., Long J.C.S., Granger Morgan M., Reed A., Sivaram V., Sweeney J., Tynan G.R., Victor D.G., Weyant J.P., and Whitacre J.F.: Evaluation of a proposal for reliable low-cost grid power with 100% wind, water, and solar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114(26), 6722–6727 (2017).

Rogelj J., Popp A., Calvin K.V., Luderer G., Emmerling J., Gernaat D., Fujimori S., Strefler J., Hasegawa T., Marangoni G., Krey V., Kriegler E., Riahi K., van Vuuren D.P., Doelman J., Drouet L., Edmonds J., Fricko O., Harmsen M., Havlík P., Humpenöder F., Stehfest E., and Tavoni M.: Scenarios towards limiting global mean temperature increase below 1.5 °C. Nat. Clim. Change 8(4), 325–332 (2018).

Jones-Albertus R., Cole W., Denholm P., Feldman D., Woodhouse M., and Margolis R.: Solar on the rise: How cost declines and grid integration shape solar’s growth potential in the United States. MRS Energy Sustain. 5, E4 (2018).

Babrowski S., Heinrichs H., Jochem P., and Fichtner W.: Load shift potential of electric vehicles in Europe. J. Power Sources 255, 283–293 (2014).

López M.A., de la Torre S., Martín S., and Aguado J.A.: Demand-side management in smart grid operation considering electric vehicles load shifting and vehicle-to-grid support. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 64, 689–698 (2015).

Aziz M., Oda T., Mitani T., Watanabe Y., and Kashiwagi T.: Utilization of electric vehicles and their used batteries for peak-load shifting. Energies8(5), 3720 (2015).

Gnann T., Klingler A.-L., and Kühnbach M.: The load shift potential of plug-in electric vehicles with different amounts of charging infrastructure. J. Power Sources 390, 20–29 (2018).

Byrne R.H., Nguyen T.A., Copp D.A., Chalamala B.R., and Gyuk I.: Energy management and optimization methods for grid energy storage systems. IEEE Access 6, 13231–13260 (2018).

Marcos J., Marroyo L., Lorenzo E., Alvira D., and Izco E.: Power output fluctuations in large scale pv plants: One year observations with one second resolution and a derived analytic model. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 19(2), 218–227 (2011).

Pourmousavi S.A., Cifala A.S., and Nehrir M.H.: Impact of high penetration of PV generation on frequency and voltage in a distribution feeder. In Proceedings of the 2012 North American Power Symposium (NAPS) (IEEE, 2012); pp. 1–8.

Shah R., Mithulananthan N., Bansal R.C., and Ramachandaramurthy V.K.: A review of key power system stability challenges for large-scale PV integration. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 41, 1423–1436 (2015).

Anvari M., Lohmann G., Wächter M., Milan P., Lorenz E., Heinemann D., Tabar M.R.R., and Joachim P.: Short term fluctuations of wind and solar power systems. New J. Phys. 18(6), 063027 (2016).

Jiang Y., Fletcher J., Burr P., Hall C., Zheng B., Wang D.-W., Ouyang Z., and Lennon A.: Suitability of representative electrochemical energy storage technologies for ramp-rate control of photovoltaic power. J. Power Sources 384, 396–407 (2018).

Kroposki B., Johnson B., Zhang Y., Gevorgian V., Denholm P., Hodge B., and Hannegan B.: Achieving a 100% renewable grid: Operating electric power systems with extremely high levels of variable renewable energy. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 15(2), 61–73 (2017).

Serban I. and Ion C.P.: Microgrid control based on a grid-forming inverter operating as virtual synchronous generator with enhanced dynamic response capability. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 89, 94–105 (2017).

Denis G., Prevost T., Debry M., Xavier F., Guillaud X., and Menze A.: The migrate project: The challenges of operating a transmission grid with only inverter-based generation. A grid-forming control improvement with transient current-limiting control. IET Renew. Power Gener. 12(5), 523–529 (2018).

Chunsheng W., Hua L., Zilong Y., Yibo W., and Honghua X.: Voltage and frequency control of inverters connected in parallel forming a micro-grid. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Power System Technology (IEEE, 2010); pp. 1–6.

Carrasco J.M., Franquelo L.G., Bialasiewicz J.T., Galvan E., PortilloGuisado R.C., Prats M.A.M., Leon J.I., and Moreno-Alfonso N.: Power-electronic systems for the grid integration of renewable energy sources: A survey. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 53(4), 1002–1016 (2006).

Marcos J., Marroyo L., Lorenzo E., and García M.: Smoothing of PV power fluctuations by geographical dispersion. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 20(2), 226–237 (2012).

Delille G., Francois B., and Malarange G.: Dynamic frequency control support by energy storage to reduce the impact of wind and solar generation on isolated power system’s inertia. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 3(4), 931–939 (2012).

Swierczynski M., Stroe D.I., Stan A.I., Teodorescu R., and Sauer D.U.: Selection and performance-degradation modeling of LiMO2/Li4Ti5O12 and LiFePO4/C battery cells as suitable energy storage systems for grid integration with wind power plants: An example for the primary frequency regulation service. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 5(1), 90–101 (2014).

Marcos J., Storkël O., Marroyo L., Garcia M., and Lorenzo E.: Storage requirements for PV power ramp-rate control. Sol. Energy 99, 28–35 (2014).

Schnabel J. and Valkealahti S.: Energy storage requirements for PV power ramp rate control in northern Europe. Int. J. Photoenergy 2016, 11 (2016).

Greenwood D.M., Lim K.Y., Patsios C., Lyons P.F., Lim Y.S., and Taylor P.C.: Frequency response services designed for energy storage. Appl. Energy 203, 115–127 (2017).

Nishi Y.: The development of lithium ion secondary batteries. Chem. Rec. 1(5), 406–413 (2001).

Goodenough J.B. and Park K.-S.: The Li-ion rechargeable battery: A perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135(4), 1167–1176 (2013).

Blomgren G.E.: The development and future of lithium ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164(1), A5019–A5025 (2017).

Dunn B., Kamath H., and Tarascon J.-M.: Electrical energy storage for the grid: A battery of choices. Science 334(6058), 928–935 (2011).

Zaghib K., Mauger A., Groult H., Goodenough J., and Julien C.: Advanced electrodes for high power Li-ion batteries. Materials 6(3), 1028 (2013).

Thorbergsson E., Knap V., Swierczynski M., Stroe D., and Teodorescu R.: Primary frequency regulation with Li-ion battery based energy storage system—Evaluation and comparison of different control strategies. In Proceedings of the 35th International Telecommunications Energy Conference (IEEE, 2013); pp. 1–6.

Hesse H., Schimpe M., Kucevic D., and Jossen A.: Lithium-ion battery storage for the grid—A review of stationary battery storage system design tailored for applications in modern power grids. Energies 10(12), 2107 (2017).

ARPA-E: Duration Addition to Electricity Storage (DAYS): Technical Overview Document. Available at: https://arpa-e.energy.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/DAYS_ProgramOverview_FINAL.pdf (accessed March 8, 2019).

Sbordone D., Bertini I., Di Pietra B., Falvo M.C., Genovese A., and Martirano L.: EV fast charging stations and energy storage technologies: A real implementation in the smart micro grid paradigm. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 120, 96–108 (2015).

Armand M.B.: Intercalation electrodes. In Materials for Advanced Batteries, Murphy D., ed. (Springer US, Boston, Massachusetts, 1980); pp. 145–161.

Janek J. and Zeier W.G.: A solid future for battery development. Nat. Energy 1, 16141 (2016).

Quinn J.B., Waldmann T., Richter K., Kasper M., and Wohlfahrt-Mehrens M.: Energy density of cylindrical Li-ion cells: A comparison of commercial 18650 to the 21700 cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 165(14), A3284–A3291 (2018).

An S.J., Li J., Daniel C., Mohanty D., Nagpure S., and Wood D.L.: The state of understanding of the lithium-ion-battery graphite solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) and its relationship to formation cycling. Carbon 105, 52–76 (2016).

Peled E. and Menkin S.: Review—SEI: Past, present and future. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164(7), A1703–A1719 (2017).

Wang A., Kadam S., Li H., Shi S., and Qi Y.: Review on modeling of the anode solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) for lithium-ion batteries. npj Comput. Mater. 4(1), 15 (2018).

Somerville L., Bareño J., Trask S., Jennings P., McGordon A., Lyness C., and Bloom I.: The effect of charging rate on the graphite electrode of commercial lithium-ion cells: A post-mortem study. J. Power Sources 335, 189–196 (2016).

Vetter J., Novák P., Wagner M.R., Veit C., Möller K.C., Besenhard J.O., Winter M., Wohlfahrt-Mehrens M., Vogler C., and Hammouche A.: Ageing mechanisms in lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 147(1), 269–281 (2005).

Zhao K., Pharr M., Vlassak J.J., and Suoa Z.: Fracture of electrodes in lithium-ion batteries caused by fast charging. J. Appl. Phys. 108(7), 073517 (2010).

Wen J., Yu Y., and Chen C.: A review on lithium-ion batteries safety issues: Existing problems and possible solutions. Mater. Express 2(3), 197–212 (2012).

Downie L.E., Krause L.J., Burns J.C., Jensen L.D., Chevrier V.L., and Dahn J.R.: In situ detection of lithium plating on graphite electrodes by electrochemical calorimetry. J. Electrochem. Soc. 160(4), A588–A594 (2013).

Deng D.: Li-ion batteries: Basics, progress, and challenges. Energy Sci. Eng. 3(5), 385–418 (2015).

Liu K., Liu Y., Lin D., Pei A., and Cui Y.: Materials for lithium-ion battery safety. Sci. Adv. 4(6), eaas9820 (2018).

Takami N., Satoh A., Hara M., and Ohsaki T.: Structural and kinetic characterization of lithium intercalation into carbon anodes for secondary lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 142(2), 371–379 (1995).

Levi M.D. and Aurbach D.: Diffusion coefficients of lithium ions during intercalation into graphite derived from the simultaneous measurements and modeling of electrochemical impedance and potentiostatic intermittent titration characteristics of thin graphite electrodes. J. Phys. Chem. B 101(23), 4641–4647 (1997).

Kaskhedikar N.A. and Maier J.: Lithium storage in carbon nanostructures. Adv. Mater. 21(25-26), 2664–2680 (2009).

Nitta N., Wu F., Lee J.T., and Yushin G.: Li-ion battery materials: Present and future. Mater. Today 18(5), 252–264 (2015).

Schipper F., Erickson E.M., Erk C., Shin J.-Y., Chesneau F.F., and Aurbach D.: Review—Recent advances and remaining challenges for lithium ion battery cathodes: I. Nickel-rich, LiNixCoyMnzO2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164(1), A6220–A6228 (2017).

Tarascon J.M. and Armand M.: Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 414, 359 (2001).

Xu K.: Nonaqueous liquid electrolytes for lithium-based rechargeable batteries. Chem. Rev. 104(10), 4303–4418 (2004).

Eftekhari A.: Lithium-ion batteries with high rate capabilities. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 5(4), 2799–2816 (2017).

Liu Q., Du C., Shen B., Zuo P., Cheng X., Ma Y., Yin G., and Gao Y.: Understanding undesirable anode lithium plating issues in lithium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 6(91), 88683–88700 (2016).

Jansen A.N., Kahaian A.J., Kepler K.D., Nelson P.A., Amine K., Dees D.W., Vissers D.R., and Thackeray M.M.: Development of a high-power lithium-ion battery. J. Power Sources 81–82, 902–905 (1999).

Ferg E., Gummow R.J., de Kock A., and Thackeray M.M.: Spinel anodes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 141(11), L147–L150 (1994).

Colbow K.M., Dahn J.R., and Haering R.R.: Structure and electrochemistry of the spinel oxides LiTi2O4 and Li43Ti53O4. J. Power Sources 26(3), 397–402 (1989).

Ohzuku T., Ueda A., and Yamamoto N.: Zero-strain insertion material of Li [ Li1/3Ti5/3]O4 for rechargeable lithium cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 142(5), 1431–1435 (1995).

Sandhya C.P., John B., and Gouri C.J.I.: Lithium titanate as anode material for lithium-ion cells: A review. Ionics 20(5), 601–620 (2014).

Yang Z., Choi D., Kerisit S., Rosso K.M., Wang D., Zhang J., Graff G., and Liu J.: Nanostructures and lithium electrochemical reactivity of lithium titanites and titanium oxides: A review. J. Power Sources 192(2), 588–598 (2009).

Madian M., Eychmüller A., and Giebeler L.: Current advances in TiO2-based nanostructure electrodes for high performance lithium ion batteries. Batteries 4(1), 7 (2018).

Wen C.J., Boukamp B.A., Huggins R.A., and Weppner W.: Thermodynamic and mass transport properties of “LiAl”. J. Electrochem. Soc. 126(12), 2258–2266 (1979).

Takami N., Kosugi S., and Inagaki H.: New SCiB™ high-safety rechargeable battery for HEV application. Toshiba Rev. 63(12), 54–57 (2008).

Takami N., Inagaki H., Kishi T., Harada Y., Fujita Y., and Hoshina K.: Electrochemical kinetics and safety of 2-volt class Li-ion battery system using lithium titanium oxide anode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 156(2), A128–A132 (2009).

Manev V. and John Shelburne J.: Method for preparing a lithium ion cell. U.S. Patent No. 8420264, April 16, 2013.

Toshiba: SCiB™ Cells. Available at: https://www.scib.jp/en/product/cell. htm (accessed October 22, 2018).

Ge H., Li N., Li D., Dai C., and Wang D.: Study on the theoretical capacity of spinel lithium titanate induced by low-potential intercalation. J. Phys. Chem. C 113(16), 6324–6326 (2009).

Wang C., Wang S., Tang L., He Y.-B., Gan L., Li J., Du H., Li B., Lin Z., and Kang F.: A robust strategy for crafting monodisperse Li4Ti5O12 nanospheres as superior rate anode for lithium ion batteries. Nano Energy 21, 133–144 (2016).

Odziomek M., Chaput F., Rutkowska A., Świerczek K., Olszewska D., Sitarz M., Lerouge F., and Parola S.: Hierarchically structured lithium titanate for ultrafast charging in long-life high capacity batteries. Nat. Commun. 8, 15636 (2017).

Marchand R., Brohan L., and Tournoux M.: TiO2(B) a new form of titanium dioxide and the potassium octatitanate K2Ti8O17. Mater. Res. Bull. 15, 1129–1133 (1980).

Brumbarov J., Vivek J.P., Leonardi S., Valero-Vidal C., Portenkirchner E., and Kunze-Liebhäuser J.: Oxygen deficient, carbon coated self-organized TiO2 nanotubes as anode material for Li-ion intercalation. J. Mater. Chem. A 3(32), 16469–16477 (2015).

Auer A., Steiner D., Portenkirchner E., and Kunze-Liebhäuser J.: Nonequilibrium phase transitions in amorphous and anatase TiO2 nanotubes. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 1(5), 1924–1929 (2018).

Zukalová M., Kalbáč M., Kavan L., Exnar I., and Graetzel M.: Pseudocapacitive lithium storage in TiO2(B). Chem. Mater. 17(5), 1248–1255 (2005).

Ren Y., Liu Z., Pourpoint F., Armstrong A.R., Grey C.P., and Bruce P.G.: Nanoparticulate TiO2(B): An anode for lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. 51(9), 2164–2167 (2012).

Arrouvel C., Parker S.C., and Islam M.S.: Lithium insertion and transport in the TiO2–B anode material: A computational study. Chem. Mater. 21(20), 4778–4783 (2009).

Dalton A.S., Belak A.A., and Van der Ven A.: Thermodynamics of lithium in TiO2(B) from first principles. Chem. Mater. 24(9), 1568–1574 (2012).

Tian B., Xiang H., Zhang L., Li Z., and Wang H.: Niobium doped lithium titanate as a high rate anode material for Li-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 55(19), 5453–5458 (2010).

Han J.-T., Huang Y.-H., and Goodenough J.B.: New anode framework for rechargeable lithium batteries. Chem. Mater. 23(8), 2027–2029 (2011).

Anh L.T., Rai A.K., Thi T.V., Gim J., Kim S., Shin E.-C., Lee J.-S., and Kim J.: Improving the electrochemical performance of anatase titanium dioxide by vanadium doping as an anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 243, 891–898 (2013).

Lin C., Wang G., Lin S., Li J., and Lu L.: TiNb6O17: A new electrode material for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 51(43), 8970–8973 (2015).

Lee Y.-S. and Ryu K.-S.: Study of the lithium diffusion properties and high rate performance of TiNb6O17 as an anode in lithium secondary battery. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 16617 (2017).

Griffith K.J., Senyshyn A., and Grey C.P.: Structural stability from crystallographic shear in TiO2–Nb2O5 phases: Cation ordering and lithiation behavior of TiNb24O62. Inorg. Chem. 56(7), 4002–4010 (2017).

Takami N., Ise K., Harada Y., Iwasaki T., Kishi T., and Hoshina K.: High-energy, fast-charging, long-life lithium-ion batteries using TiNb2O7 anodes for automotive applications. J. Power Sources 396, 429–436 (2018).

Wu X., Miao J., Han W., Hu Y.-S., Chen D., Lee J.-S., Kim J., and Chen L.: Investigation on Ti2Nb10O29 anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 25, 39–42 (2012).

Griffith K.J., Wiaderek K.M., Cibin G., Marbella L.E., and Grey C.P.: Niobium tungsten oxides for high-rate lithium-ion energy storage. Nature 559(7715), 556–563 (2018).