Abstract

Background

People live longer, and frailty has become an important problem in the acute hospital setting. Increasingly the association between frailty and hospital-acquired complications has been reported. However, the overall burden of frailty in this setting has not been described. Therefore, we undertook this study to describe the association between frailty and the risk of hospital-acquired complications among older adults across our five acute hospitals and to estimate the overall burden of frailty attributable to these complications.

Methods

Consecutive admissions among women and men aged ≥ 65 years across our local health district’s five acute hospitals, between January 2010 and December 2020, were included to investigate the association between the number of cumulative frailty deficit items and hospital-acquired complications and infections. The numbers of cumulative frailty deficits are presented in four groups (0–1 item, 2 items, 3 items, and 4–13 items). Individual events such as falls, delirium, pressure injuries, thromboembolism, malnutrition, and multiple types of infections are also presented. The overall burden of frailty was estimated using a population-attributable-risk approach.

Results

During the study period there were 4,428 hospital-acquired complications, among 120,567 older adults (52% women). The risk of any hospital-acquired complication (HAC) or any hospital-acquired infection (HAI) increased as the cumulative number of frailty deficits increased. For the 0–1 deficit item group versus the 4–13 items group, the risk of any HAC increased from 5.5/1000 admissions to 80.0/1000 admissions, and for any HAI these rates were 6.2/1000 versus 58.2/1000, respectively (both p-values < 0.001). The 22% (27,144/120,567) of patients with 3 or more frailty deficit items accounted for 63% (2,774/4,428) of the combined hospital-acquired complications and infections. We estimated that the population-attributable risks of any hospital-acquired complication or infection were 0.54 and 0.47, respectively.

Conclusion

We found that an increasing number of cumulative frailty deficit items among older patients are associated with a higher risk of hospital-acquired complications or infections. Importantly, frail older adults account for most of these adverse events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Geriatricians have long recognised the “hazards of hospitalisation” for older adults, age being consistently identified as the strongest predictor of hospital-acquired complications such as falls, delirium, pressure injuries, thromboembolism, malnutrition, and infections (1, 2). Most of these adverse events among older adults admitted to hospital have been suggested to be a consequence of frailty, acute illness, and the hospital environment (see Figure 1) (2). Coupled with this are the gains in life expectancy and a shift in mortality from degenerative diseases to older ages, which have been proposed as the fourth stage of the epidemiologic transition, “the age of delayed degenerative disease” (3). Increased life expectancy is not without negative consequences, the most problematic in the acute hospital setting is frailty among older adult admissions (1).

Frailty has been reported to be an independent predictor of hospital-acquired complications among older adults in various acute hospital settings (1, 4–7). However, the overall burden of frailty and hospital complications among older adults admitted to the hospital has not been specifically investigated. Therefore, we undertook this study to describe the proportion of hospital-acquired complications among older adults who are frail and to estimate the overall burden of frailty using a population-attributable risk approach (8).

Methods

Setting and participants

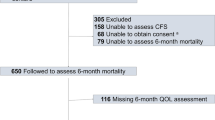

We included all patients aged 65 years or more, who had at least one admission to one of our five acute public hospitals across the South Western Sydney (SWSLHD) Local Health District between January 1st 2010 and December 31st 2020. Our analysis is based on the first (index) admission during this period. We have included both unplanned (emergency) and planned admissions, with at least an overnight stay in the hospital, excluding day-only admissions such as those for renal replacement therapy and ambulatory care.

Estimating frailty status on admission to hospital

Frailty among these older patients was estimated using a cumulative deficit approach developed by Clegg et al (9), using clinical coding (ICD-10-codes) of 36 deficit items (Appendix 1). We have found locally that this approach to estimating frailty performs well in predicting mortality (c-statistic = 0.70), and inspection of survival curves from our hospital population are comparable to those from Clegg’s population-based development model, in which increasing deficit items groups are related to increased mortality (9). We have also previously shown that this cumulative deficit approach using coded hospital data, performs comparably to Rockwood’s Clinical Frailty Scale in predicting an acute episode of delirium in the adult intensive care setting (both c-statistics = 0.70) (10). In our cohort, cumulative deficit items were identified from pre-existing conditions at the time of hospital admission. These were coded as part of routine hospital administrative data collection. Specifically, four cumulative frailty item groups were derived based on the distribution of items: 0–1 item; 2 items; 3 items; and 4–13 items. Grouping is based on using the lower and upper 99th population percentile of deficit items (in our case 0 and 4). This range is divided into four equally distanced groups as suggested by Clegg et al (9). Using this approach the two highest deficit items groups are considered moderately and severely frail, respectively. Using this criterion we have used 3 or more deficit items to indicate the presence of frailty on admission to the hospital. Rather than using an index we present the actual number of items. The distribution of the deficit items in our cohort is presented in Figure 2.

Outcomes of interest

Our main outcomes of interest were based on Hospital Acquired Complications (HACs): (1) falls; (2) pressure injury; (3) delirium (4); malnutrition; and (5) thromboembolism. And Hospital Acquired Infections (HAI): (1) multi-resistant organisms (MRO); blood-stream infections (BSI); surgical site infections (SSI); catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI); and acute pneumonia (AP). All these complications are routinely identified and coded as part of our national hospital coding standards, using ICD-10-AM codes and specifically identified as being hospital-acquired by an associated hospital-onset flag code (11).

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the cohort of older adults admitted to our hospitals are presented using descriptive statistics, and the number of adverse events are presented as rates with associated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), per 1000 admissions. The association between an increasing number of frailty deficit items and the risk of specific hospital-acquired adverse events (HAC, HAI) was assessed using Poisson regression, adjusted for age and sex. Estimates are presented as Rate Ratios (RR) and associated 95% CI (12). The numbers of cumulative frailty deficit items are presented in four groups (0–1 item, 2 items, 3 items, and 4–13 items). The population-attributable risks of any HAC or HAI, based on the proportion of frail older adults (3 or more deficit items, as suggested by Clegg et al (9)) were also estimated (8, 13).

Where, popAR = population-attributable risk, p = the proportion of exposure among the given population (in our case the proportion of older adults with 3 or more deficit items), and RR = adjusted (age and sex) Risk Ratio. The adjusted model areas under the receiver operator characteristic curves and associated 95% CI are presented (AUC). The absolute risk of these adverse events during a hospital stay based on age, sex, and the number of cumulative deficit frailty items groups are presented, with 95% CI. All data management was undertaken using SAS (version 9.4), and all statistical analyses were performed using the R language for statistical computing (14).

Ethical Considerations

This project was reviewed by the SWSLHD Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee and was determined to meet the requirements of the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007). Due to the use of routinely collected hospital separation data, the need for individual patient consent was waived (HREC code – ETH11883).

Results

During the study period, there were 4,428 hospital-acquired complications, among 120,567 older adults. The characteristics of the study participants, at the index admission, based on the cumulative frailty deficit item groups, are presented (Table 1). Most patients (57.2%) had 0–1 deficit item on admission, 20.3% had 2 items, and 22.5% had 3 or more cumulative frailty deficit items (Table 1). The average age increased across the groups of increasing cumulative frailty deficit items and ranged from 76.4 years (SD 7.5), in the 0–1 cumulative frailty deficit item group to 80.1 (SD 7.7) in the 4–13 items group. The distribution of females (52%) was similar across cumulative frailty deficit items groups (p-value = 0.15), and the proportion of emergency admissions and those associated with injury increased across cumulative frailty deficit items groups (both p-values < 0.001). The frequency of the most common cumulative frailty deficit items increased across the four groups also (all p-values < 0.001) (Fig 2). Furthermore, length of stay increased with an increasing number of frailty deficit items, ranging from 3 days (IQR 1 to 5) to 12 days (IQR 6 to 22) across the four cumulative frailty deficit items groups (p-value < 0.001), and the associated rate hospital of mortality ranged between 2% (1,089/68,980), and 12% (1,209/13,358) across the cumulative frailty deficits item groups.

Risk of hospital-acquired adverse events based on increasing cumulative frailty deficit items

The associations between increasing frailty deficit items and hospital complications are presented in Table 2, and hospital-acquired infections in Table 3. Overall, the risk of any HAC increased as the number of cumulative frailty deficit items increased (Table 2), with rates per 1000 admissions ranging between 5.3 (95% CI 4.7 to 5.9) to 80.0 (95% CI 75.2 to 85.0) (adjusted p-value for trend < 0.001) The associated model adjusted for age and sex had an AUC of 0.78 (95% CI 0.77 to 0.76). The population-attributable-risk of any HAC due to having 3 or more cumulative frailty deficit items was estimated to be 0.54. The risks of the specific HAC events (falls, pressure injury, delirium, malnutrition, and thromboembolism) were all observed to increase with the number of frailty deficit items (Table 2). The various associated AUCs for the adjusted models for these outcomes ranged between 0.72 and 0.83, with the strongest discriminatory value observed for falls. The risk of any HAI increased as the number of cumulative frailty deficit items increased, with rates per 1000 admissions ranging between 6.2 (95% CI 5.6 to 6.8) to 58.5 (95% CI 54.4 to 62.7) with an adjusted p-value for trend < 0.001. The associated model adjusted for age and sex had an AUC of 0.74 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.75). The population-attributable risk of any HAI having 3 or more cumulative frailty deficit items was estimated to be 0.47. The risks of the specific HAI events (MRO, BSI, SSI, CAUTI, and acute pneumonia) were all observed to increase with the number of frailty deficit items (Table 3). The various associated AUCs for the adjusted models for these outcomes ranged between 0.71 and 0.79.

The distributions of cumulative frailty deficit item groups and each hospital-acquired adverse event are presented in Figure 3. The 22% (27,144/120,567) of patients with 3 or more frailty deficit items accounted for 63% (2,774/4,428) of the combined hospital-acquired complications and infections. The absolute risk of each of the HAC or HAI adverse events, based on age, sex, and cumulative frailty deficit items group are presented in Figure 4. For example, the absolute risk of any HAC during a hospital stay was observed among males in the 4–13 cumulative frailty deficit items group, to be between 8% and 10% across all age groups, and the risk among women in this group ranged between 6% and 7%. Both men and women in the lowest cumulative frailty deficit item group (0 to 1) had an absolute risk of any HAC or HAI below 1%.

The proportion of adverse events is based on the no. of cumulative frailty deficit items (CFI)

Any Hospital Acquired Complications (any HAC): Fall, pressure injury (HAPI), Delirium, Malnutrition, thromboembolism (TE). Any Hospital Acquired Infections (any HAI): multi-resistant organisms (MRO), bloodstream infections (BSI), surgical site infections (SSI), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTI), and acute pneumonia (AP).

Discussion

In this large study of over 120,000 hospitalised older adults aged ≥65 years, we found that most hospital-acquired complications are strongly associated with an increasing number of cumulative frailty deficit items. For example, when the 0–1 deficit item group versus the 4–13 items group were compared, the risk of any HAC increased from 5.5/1000 admissions to 80.0/1000 admissions, and for any HAI these rates were 6.2/1000 versus 58.2/1000, respectively (both p-values < 0.001). We estimated that approximately 60% of these adverse events occurred among the 22% of older patients who were considered frail on admission to the hospital (3 or more deficit items). These results underscore the high burden of adverse events among older adults who are admitted to the hospital with frailty.

Frailty in community-dwelling older adults has been associated with a greater risk of falls (15, 16), delirium (17), and mortality (18–20). In the hospital setting, frailty is associated with adverse events among a wide range of patients (6, 7), including in-hospital falls, delirium, pressure injury, and mortality (1). Our large study of a cohort of older hospitalised patients highlights the burden of frailty in terms of hospital-acquired adverse events and the need for high-quality, well-designed studies to explore the potential role of models of care that focus on this vulnerable population in the acute hospital setting. Moreover, up to 80% of hospital deaths occur in older frail people (21). Most of these were not recognised as being near the end of life before hospital admission.

Our results need to be considered in the context of some potential weaknesses. Our method of estimating the burden of frailty among older patients was based on coded hospital separation data, for both our exposure and outcomes, this could result in some potential bias. In both cases, we feel the exposure (frailty) and the outcomes of interest (hospital adverse events) are under-reported using this type of data, therefore our estimates of risk may be biased toward the null. Even though our overall number of deficit items was lower than those obtained by Clegg (1) in the development of the electronic cumulative frailty index, our distribution of categories was very similar, with approximately half of our cohort in the lowest deficit group (0–1 deficit items), which Clegg referred to as ‘Fit’. Importantly, our observed relationship between an increasing number of frailty deficit items and the risk of adverse events in the hospital setting was very strong and consistent across events. Furthermore, we have been able to focus on a range of hospital-acquired adverse events in one study.

The clinical implications of our findings when considered in the context that clinical staff currently spend time and resources separately documenting risks and management protocols for individual complications such as pressure injuries, falls, and delirium. This study and others like it suggest that measuring frailty at hospital admission as a surrogate for these and other complications as well as a platform for important discussions around prognosis and management plans may provide a more appropriate approach to patient-centred management.

Conclusion

High rates of hospital-acquired adverse events in older people are associated with frailty. Importantly, we observed that most of these events occur among a minority of older patients who were frail on admission to the hospital, supporting the need for trials of targeted multi-model interventions delivered by all clinicians in the acute care setting. These results highlight the burden of adverse events among frail older adults who are admitted to the hospital and the need for a more holistic and coordinated response by healthcare providers to frailty in the acute hospital setting. This response will need to be acceptable and fit for the purpose - addressing the specific needs and wishes of frail older patients and their families.

References

Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Rikkert, M. O. & Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 381 North American Edition, 752–762 711p (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9

Creditor, M. Hazards of Hospitalization of the Elderly. Annals of Internal Medicine 118, 219–223 (1993). https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011%m8417639

Olshansky, S. J. & Ault, A. B. The Fourth Stage of the Epidemiologic Transition: The Age of Delayed Degenerative Diseases. The Milbank Quarterly 64, 355–391 (1986). https://doi.org/10.2307/3350025

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). Australian safety and quality framework for health care. (ACSQHC, Sydney, 2010).

Boucher, E. L., Gan, J. M., Rothwell, P. M., Shepperd, S. & Pendlebury, S. T. Prevalence and outcomes of frailty in unplanned hospital admissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of hospital-wide and general (internal) medicine cohorts. EClinicalMedicine 59, 101947 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101947

Cunha, A. I. L., Veronese, N., de Melo Borges, S. & Ricci, N. A. Frailty as a predictor of adverse outcomes in hospitalized older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 56, 100960 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2019.100960

Gong, S. et al. Association Between the FRAIL Scale and Postoperative Complications in Older Surgical Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anesth Analg 136, 251–261 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006272

Porta, M. A dictionary of epidemiology. (Oxford university press, 2014).

Clegg, A. et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing 45, 353–360 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw039

Frost, S. A. et al. Frailty in the prediction of delirium in the intensive care unit: A secondary analysis of the Deli study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 68, 214–225 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.14343

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). Hospital-acquired complications (HACs), <https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/indicators-measurement-and-reporting/hospital-acquired-complications-hacs> (2024).

Breslow, N. E. & Day, N. E. Statistical methods in cancer research. (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1980).

Miettinen, O. S. Proportion of disease caused or prevented by a given exposure, trait or intervention. Am J Epidemiol 99, 325–332 (1974). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121617

R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2017).

Bandeen-Roche, K. et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women’s health and aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 61, 262–266 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/61.3.262

Eeles, E. M. et al. Hospital use, institutionalisation and mortality associated with delirium. Age and ageing 39, 470–475 (2010).

Ensrud, K. E. et al. Comparison of 2 frailty indexes for prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and death in older women. Arch Intern Med 168, 382–389 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2007.113

Hubbard, R. E. et al. Frailty status at admission to hospital predicts multiple adverse outcomes. Age and Ageing 46, 801–806 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx081

Ní Chróinín, D. et al. Older trauma patients are at high risk of delirium, especially those with underlying dementia or baseline frailty. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open 6, e000639 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1136/tsaco-2020-000639

Rockwood, K. et al. Prevalence, attributes, and outcomes of fitness and frailty in community-dwelling older adults: report from the Canadian study of health and aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59, 1310–1317 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/59.12.1310

Almagro, P. et al. Multimorbidity gender patterns in hospitalized elderly patients. PLOS ONE 15, e0227252 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227252

Funding

Funding note: Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors contributions: SA Frost: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing – original draft, and writing – review & editing. D Ni Chroinin: conceptualisation, formal analysis, methodology, writing – original draft, and writing – review & editing. L McEvoy: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – review & editing. N Francis: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – review & editing. V Deane: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – review & editing. M Bonser: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – review & editing. C Wilson: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – review & editing. M Perkins: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – review & editing. B Shepherd: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – review & editing. V Vueti: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – review & editing. R Shekhar: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – review & editing. M Mayahi-Neysi: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – review & editing. K Hillman: conceptualisation, methodology, writing – review & editing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Considerations: This project was reviewed by the SWSLHD Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee and was determined to meet the requirements of the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007). Due to the use of routinely collected hospital separation data, the need for individual patient consent was waived (HREC code – ETH11883).

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Appendix 1

. Cumulative frailty deficits items (ICD-10-AM codes)

Rights and permissions

Open Access: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Frost, S.A., Ni Chroinin, D., Mc Evoy, L. et al. Most Hospital-Acquired Complications among Older Adults Are Associated with Frailty: The South-Western Sydney Frailty and Hospital-Acquired Complications Study. J Frailty Aging (2024). https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2024.60

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2024.60