Abstract

Leadership has been a topic of great interest for researchers, business people, educators, and government officials alike over the years. Leadership as a theoretical construct has undergone a great deal of changes as a result of changes such as modernization, globalization and most recently digitalization. Taking into account the various changes that the internet and cloud computing has introduced in the organizational systems and processes across the globe, it is prudent to understand the relationship between leadership and digitalization to foresee how leaders should prepare themselves to cater to the challenges of the future. Leadership is indeed an ever-evolving concept, and so is technology; of which digitalization is an outcome. Most inquiries about such a relation are being well executed by the western cultures. Exploring the relationship between leadership and digitalization in the eastern cultures, especially India becomes more significant; as the technology is booming and drastically changing how daily activities are carried out as an influence of digitalization. With over 40% of the Indian population subscribed to the internet, and through the efforts made by the public and private sectors, India is on the way to being a technologically advanced country. India is also the largest base of digital consumers. Leaders struggle to lead in such challenging situations; which are becoming more volatile. It is imperative to examine what capacities, abilities and competencies leaders already have and what they need to further improve upon, in order to lead effectively in the digital world. To examine the overall context of Indian traditional leadership, leader–member exchange is seen to be a relevant theory. At last, challenges and gaps are discussed and the notion of “creative personality” is recommended for Indian leaders to cater to the digital changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Need for exploring digital leadership in India

Warren Bennis, in “Leadership in a Digital World: Embracing Transparency and Adaptive Capacity” describes how digital business strategy is an essential transformational concern when it comes to leadership. Bennis claims that data-driven transparency will pave the way for future change. The capability to bring about this change lies with the leader. Consequently, just as doctors adapt and use new innovations in medicine, leaders need to adopt this transparency. He also emphasises how critical the qualities of being adaptive, resilient and open to change are for a leader. These qualities are an amalgamation of innate personality traits as well as learnings from experiences and mistakes. Being able to embrace the change and transparency is key to effective leadership.

The increased use of the internet was further propelled by the drop in cost and increased accessibility to internet connections and smart devices. Being second only to China, India has 560 million subscribers, and the average user consumes 17 h of content on social media apps per week. The Indian public sector has also played an integral role in the fast-paced digitisation. Aadhaar, the digital identity program and the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax Network have played a major role in encouraging businesses to go digital. In the private sector, innovative strategies such as Jio’s plan of combining low-cost smartphones with their mobile services has stirred competitive pricing throughout the industry. The 95% drop in the data costs as of 2013 has resulted in a 153% growth in data consumption (McKinsey Report 2019).

There is an ever-increasing need for today’s leaders to understand current digital needs, be able to cater to those needs through upgrading themselves and the processes in organizations, be able to gauge future demands, be able to train their followers to perform in the changing digital times and most importantly how to lead by considering followers needs pertaining to the digital world not forgetting the cultural context in which all this interaction takes place. To achieve such a goal, leaders’ competencies play an important role. Competencies often used synonymously with skills especially in the Indian context, are in fact more than skills.

Competencies are a conflation of knowledge, skills, attitude, values, and norms. Competencies go beyond merely skillful execution of tasks in favourable conditions. A competent leader should be able to perform optimally also in unfavourable, new and unforeseen conditions. According to Erpenbeck and Rosenstiel (2003), competencies entail engaging in creative thinking processes, they are a result of dispositions of self-organization in human interaction. Competencies can be defined based on one’s self-organization abilities. Skills, knowledge and abilities can be directly tested; however, competencies can only be observed or indirectly measured retrospectively by considering the personal dispositions, by measuring or observing the actual behaviour and through performance measurement. Being able to execute tasks effectively and innovatively in a new and unpredictable situation may serve as a basis for competent leadership behaviour. “Competencies are based on the foundation of knowledge, constitute values, disposed as abilities, consolidated through knowledge and realized on the basis of will” (Bharadwaj et al. 2013, p. 490). Considering this notion of competencies, it would prove significant to investigate which competencies leaders require in traditional leadership and which competencies they would require in the new digital world. Research conducted in the Indian context suggests a gap in understanding what the leaders can provide and what the digital world demands. The current article aims to bridge this gap by reviewing empirical and other forms of investigative reports from well-established and reputed companies on the LMX theory, its relevance in the digital world, digitization process in India, challenges faced by leaders in catering to digital demands and finally competencies for the digital leadership (Bharadwaj et al. 2013).

2 Exploring Indian leadership in the context of LMX

Leadership like any other social transaction is a two-way process and relationship-based. The unidimensional leadership theories focusing solely upon the leader (leader characteristics and styles) are thus being supplemented if not replaced, by theories like the leader–member exchange (LMX), which considers leadership to be a multidimensional social process and thus allows for influence by several factors like the cultural context of the relationship. According to research, national culture and leadership are interdependent (Anand et al. 2011). While leadership plays a critical role in moulding culture (Schein 1985 as cited in Anand et al. 2011) and is a piece in the cultural processes that are performance-related (Saffold 1988), it is also conditional on the culture (House et al. 2004). National culture has a rich history (Clark 1970 as cited in Anand et al. 2011), and is integral while generating values and meanings that are shared by the coming generations. Researchers have found a strong relationship between the expectations from leaders as to how they behave and the national culture (Gelfand et al. 2007). In order to help make a smooth transition from traditional to digital leadership, consideration of the cultural context thus becomes imperative. As India stands at the helm of transforming and progressing rapidly in terms of incorporation of technology in management, an overview of the historical leadership patterns and the status quo is required to plan further steps towards digital leadership. This paper thus attempts to discuss the specific considerations and challenges when implementing digital leadership, and also provides suggestions for the same in terms of specific competencies. The LMX theory has been considered as the primary theoretical basis for this discussion.

3 Traditional Indian leadership

Since centuries India has incorporated ideologies and practices from around the world with reference to governance and management. The treatise ‘Arthãshastra’ was one of the earliest detailed descriptions of notions of financial administration, trade and commerce, and management of people. These ideas have knowingly or unknowingly become an integral part of organisational thinking in the country (Rangarajan 1992; Sihag 2004). When trade increased and led to the establishment of ties with the Romans, their systematic governance methods found their way into India by 250 A.D. For a couple of centuries after that, the Gupta Dynasty helped the establishment of rules and regulations for governance and management systems. Later, from about 1000 A.D., Islamic rulers influenced many areas of trade and commerce in the country. The British colonial rule emerged as the next powerful force that influenced the managerial history of India for almost two centuries (Chatterjee 2007). The ideas of leadership emerging from these ideologies of ancient wisdom too, therefore, continue to play a major role in the emergence and functioning of leadership in India.

In contemporary times, the Indian management, while being rooted in ancient wisdom, is also impacted by the complexities of modern global perspectives. Though the societal values have largely remained anchored in ancient ideology, corporate priorities and values of global linkages have started entering mainstream management. This transition period poses a milieu of challenges as well as opportunities.

4 LMX in the Indian context

Research studies focusing on LMX in the non-western context have usually demonstrated constricted relationships between job satisfaction, leader trust, procedural justice, OCB and LMX, and have thus shown that when it comes to the outcomes of LMX, culture matters. Since cultural norms are difficult to change or adjust, they often end up becoming challenges for the leaders. Thus, leaders work towards creating new symbols that also align with the pre-existing cultural norms. Dismantling hierarchies using open communication, making collaborative software and strategically hiring new employees that serve to fulfil the vision of the organization. When applying the LMX in the Indian context, the crucial aspects to be considered include the broad cultural orientation of the country (in terms of being a collectivistic country), the traditional pattern of leader–member relationship (characterized by high power distance) and the position of the leader (from a predominant paternalistic tradition). The power distance, as well as the individualism–collectivism, have implications in the results of LMX (Anand et al. 2011).

5 LMX and individualistic vs. collectivistic cultures

When it comes to the vertical-collectivistic cultures, they consider themselves as interdependent and give emphasis to adjusting individual goals to match the collective interests, the perceived duties as well as the commitment to social behaviour (Triandis 1995 as cited in Rockstuhl et al. 2012). They also hold the authority at higher regard due to the power distance orientation being higher (Shavitt et al. 2006). As a result, individuals in a vertical-collectivistic culture respond to those in positions of power not only because of personal relationships but also because it is a part of their role in society (Dickson et al. 2003). In the end, due to the stronger compliance to and respect for authority that is associated with vertical-collectivism, the concept of LMX has weaker effects in these cultures.

6 LMX and high vs. low power distance setups

According to Hofstede (2001), power distance refers to the degree to which individuals are accepting of the social stratification and unbalanced allocation of power, while the concepts of individualism and collectivism explore how one sees themselves as part of the collective (Rockstuhl et al. 2012).

In the context of high power distance, people tend to give the views and decisions of the authority figures a lot of importance. The decisions they make are accepted by all. On the other side of the spectrum, low power distance societies prefer to have power over their decisions, autonomy is of utmost importance and an excessive assertion of dominance by leaders is uncomfortable (Anand et al. 2011).

Cross-cultural research shows that when there is a high power distance; leaders have centralized power and high control of the decisions such as employees’ compensation and benefits which is an important forerunner for forming a good LMX relationship (Aryee and Chen 2006). While those in a low power distance believe in the concept of self-management and solving problems on their own (Adler 1997; Kirkman and Shapiro 1997 as cited in Anand et al. 2011). Thus, the process of social exchange that is observed in high-quality LMX relationships is more prominent in high power distance societies than in low power societies (Anand et al. 2011).

In Indian organizations, ranks are on the office doors, there are separate eating spaces for the managers and employees; the status of an employee is dependent on the employment benefits (Chhokar et al. 2007). Embracing high-power distance does not differ with the status, in the GLOBE study all respondents from India showed high scores in the power distance index, despite their social status (House et al. 2004).

7 LMX, paternalistic leadership and age of the leader

The traditional and patriarchal family structure that most Indians grow up in, is an environment where they are expected to obey their father or family head (Sinha 1990 as cited in Pellegrini et al. 2010). An ethnographic study by Seymour and Seymour (1999) showed that children in Indian families are taught that their needs are not as important as submitting to the authority figures and this helps to maintain harmony. There is a similar structure in Indian organizations, where employees on the lower end of the chain follow a procedure to communicate with the higher-ups (Zaidman and Brock 2009 as cited in Pellegrini et al. 2010). Consequently, employees are meant to obey the leader and adopt the leader's values as their own (Cheng and Jiang 2000 as cited in Pellegrini et al. 2010). The conjunction between benevolence and authority reflect the qualities of a traditional father figure, someone who is nurturing, trustworthy but also authoritative, and a disciplinarian at the same time (Sinha 1990). In Indian families, social support plays a huge role in overcoming difficulties. Long-term relationships are given more focus and this is translated into the practices of HR in companies. When it comes to compensation, the seniority of the employee plays a huge role (Erez 1994). Selection and hiring also often are affected by the connections and relations the applicants have with the association and those with the most valuable connections usually is the one that is deemed to have the most qualifications (Gelfand et al. 2004).

The characteristic social patterns observed in India and similar collectivistic cultures reflect paternalistic leadership—a concept that has gained a lot of traction in the context of non-western literature (Aycan 2006; Farh et al. 2008; Pellegrini et al. 2010). Paternalism includes the leaders and managers giving attention not only to providing career support but also paying attention to the employee's personal lives when they are not working (Gelfand et al. 2007). When it comes to paternalistic leaders they take this concern for the employees and integrate it with their control over the employee's decision making (Martinez 2005). In Latin America, Asian and Middle Eastern organizations, this has proven to be an efficient managerial approach (Cheng et al. 2004; Osland et al. 1999; Pellegrini and Scandura 2006 as cited in Pellegrini et al. 2010). According to The Global Leadership and Organizational behaviour Effectiveness (GLOBE) study (House et al. 2004), this form of leadership is found in countries that have high power distance and are collectivistic. Thus, it is also prominent in India (Aycan et al. 2000; Mathuret al. 1996). The study by Aycan et al. (2000) supported this claim, showing that paternalistic values were seen more in countries like India and China as compared to individualistic countries like Germany.

In paternalism, the subordinates reciprocate the leader's benevolence by showing loyalty and compliance. While the leaders provide resources while the employees give the leader their devotion. These relationships work on the central theme that the power dynamics are unbalanced. Indians strive to find someone who acts as a guru to them, one who can integrate both maternal and paternal symbols, and provide a sense of authority and amity (Nagpal 2003; Kakar 1978 as cited in Pellegrini et al. 2010). The important characteristics of successful leadership in the Indian context involve a dependent relationship, a power distance and intimacy. The GLOBE interviews also showed that respondents find those who have an intuition in matters regarding employees, and act as a parent figure are effective leaders (Chhokar et al. 2007).

Age and the individual's social standing also plays a huge role when it comes to how much respect one receives, this is especially seen in developing traditional societies. In India, seniors being formally addressed by their last names is a common practice. The Indian culture also emphasises on how “interpersonal interdependence” and social responsibilities are of utmost importance (Kakar 2008). The concept of interdependence leads to a state of commitment, liability and a sense of loyalty, these characteristics are looked highly upon, paternalism, thus, has a positive effect on the worker's attitude. In paternalistic societies, these characteristics translate into interpersonal relationships that may transpose into a sense of commitment to the organization as well. In countries like India, effective leadership entails interpersonal relations and investment in personal difficulties. There is also a hierarchical system that closely resembles the relationships in a paternalistic society that is due to the high power distance. Thus, paternalistic leadership may work extremely well in Indian organizations and add to the quality of LMX relations in India (Pellegrini et al. 2010).

8 Digitalization in India

Before discussing the process of digitalization, explaining the distinction between digitalization and digitization is inevitable. Digitization is the process of transforming analogue data into its virtual form. Over the past decade, everything from music to money transactions has a new digital counterpart. Digitalization, however, is the perfect combination of technological advancements and human values. It is not just about getting results but also the process. Digitalization as a process understands and facilitates the impact of information and digital technologies on subsequent business practices. Embracing digitalization empowers organizations to accept and assimilate more efficient business practices which eventually adds value to all stakeholders in the business. The ultimate goal of digitalization is not only to reduce operational costs, but also magnifying the business value for individuals, companies, and societies. (Li et al. 2016). Digitalization is the new process of getting things done as well as providing an outstanding experience to the customer by taking advantage of the advancements in technology. A leader's contribution to the transformation to a community of knowledge and their expertise in technology defines digital leadership. Digital leaders have an obligation to stay on track with the new advancements and have a genuine curiosity and thirst for knowledge. They should possess the skills to not only identify patterns and trends in areas like big data and cloud computing but also use these resources to their fullest capacity. Being able to identify and fill the gaps in their knowledge is equally essential (Reddy 2018).

Sahyaja and Rao (2018) describe some aspects of the digital age. They document that the process of digitalization accelerated, with the development of personal computers such as the Simon in 1950, Apple II in 1977 and IBM PC in 1981 (Bounfour 2016; Collin et al. 2015; Vogelsang 2010). The impact of digitalization was far more due to the introduction of the ‘World Wide Web’ (Ibid) (Berman and Marshall 2014; Collin et al. 2015; Tapscott 1996; Vogelsang 2010). The process of digitalisation and its effects is termed as “digital transformation” (Berman 2012; Bounfour 2016; Chew 2015; Coyle 2006; Housewright and Schonfeld 2006 as cited in Sahyaja and Rao 2018). Sahyaja and Rao further document six characteristics of digital age:

-

1

Interconnectedness

-

2

Diminishing lag in time and the abundance of data

-

3

Added transparent and complexity

-

4

A flatter hierarchy and fewer personal boundaries

-

5

Decision facilitator and improving integrity

-

6

Humanising effect

Taking into account the digitalization process and the characteristics of the digital age and the constantly changing digital requirements it is essential to consider the effects of this process on the functioning of organizations. There is no doubt that leadership is the apex for any organization to adapt to digital changes, improve processes and productivity. Digital leadership is characterised by the use of an organisation's digital resources to achieve organisational aims and goals. This may be at two levels—individual or organisational. Individual digital leadership is often taken up by the Chief Information Officer. A digital leader at the organisational level is one that takes advantage of the resources they have to get an edge over their competitors. They are willing to analyse how information technology can be used to make them more receptive to the requirements of their customers and changing business needs. Effective digital leadership can help a business set up better workflow and methods that allow new operations. According to Westerman et al. (2014), the leadership qualities necessary for success lies in the leaders’ ability to:

-

1

Create a digital vision that is transformational in nature

-

2

Engage their employees and empower them

-

3

Make digital governance their focus; and,

-

4

Create a framework for digital leadership

Westerman et al. further quote “Digital governance is the method of guiding an organisation's digital activities towards a strategic vision and empowering and merging IT leaders and the current business methods, laying the foundation for digital leadership” (Westerman et al. 2014, p. 133–135).

9 Digital gap among Indian businesses

As mentioned earlier, the digital gap in Indian business to some extent can be understood if the digital divide in Indian context is scrutinized. Growth and business advancement as a result of the digitization process is not uniform in India and consequently results in digital gaps. Maiti et al. (2020) explored the issues of digitalization and development in India to understand whether the novel ICT based technological paradigm facilitates the development or in fact creates more hurdles in the Indian context. They suggest two ways of looking at this question. The first one is more promising which suggests that for developing countries the digitization process has brought along new opportunities to grow and upgrade by creating and disseminating new information through communication technologies. They mention some success stories of Asian NICs (Newly Industrialized Countries) such as Singapore, Korea, Taiwan, where appropriate investment in digital infrastructure and need-based skill development have led to a successful technological developmental strategy. The second perspective is less optimistic, where in the new paradigm based on ICT is creating hurdles. For some countries grappling with demands of ICT based competition business have to face is a matter of concern. What is specifically a major concern is the development of skills, competencies required for to survive the ICT based competition (Fagerberg and Godinho 2005).

To reiterate the above mentioned point, McKinsey Report (2019) presents the findings of a detailed survey that consisted of 664 Indian companies of varying sizes that they administered to determine how digitised these organisations were. This was the India Firm Digitisation Survey, which consisted of 50 items relating to the organisation's digital systems. They also studied their underlying characteristics, projects and attitudes that drove them towards digitization. This survey was used to put together the MGI India Firm Digitisation Index. This was done in order to get a better understanding of the commonalities that the leaders of these organisations share. Digital technology demands digital thinking and therefore digital leadership is of prime importance. To benefit from the digitization process, leaders must develop primarily in two areas—one is digital and the second one is humanitarian (Cortellazzo et al. 2019). Digital adaptation has been successful for some kind of organizations (Berghaus and Back 2016; Westerman et al. 2014), the types of organizations which have been successful in adapting to new digital tools and technologies belong to industry sectors of retail, banking and other high-tech sectors Westerman et al. (2014). Nevertheless, digital transformation can be a challenge considering the fact that many organizations may face several difficulties such as understanding the new technology, figuring out ways in which the new technology can be operationalized, training all stakeholders to effectively use the technology, deal with resistance to change and adapt to the new technology. Reddy (2018) mentioned a challenge of inter-relation between digital transformation and organizational culture and the role of cross-generational communication. In the Indian context, work relationships are not merely transactional but quite personalized (Sinha 1990). Gupta (1991) (as cited in Reddy 2018) states relationship and power dynamic is sustained through a tendency to put self in a secondary position putting others first and engaging in behaviours such as giving away, sacrificing and self-denial. It is next to impossible to define a uniform pattern in culture in the Indian context considering its eclectic demographics (Sinha 1990 as cited in Reddy 2018); some more prevalent cultural components such as submissiveness, fatalism, power consciousness, possessiveness towards subordinates, fear of independent decision-making, and resistance to change (Sparrow and Budhwar 1997) can affect exercising effective leadership in digital context. It can be inferred that considering this peculiar socio-cultural Indian setting, which is nested in legal, political, and economic context, poses further challenges in accepting digital transformation, adapting oneself to digital changes and catering to digital changes by embracing technology, making suitable changes in operations for organizations to function efficiently (Reddy 2018).

Catering to the demands of the digital age and to be able to bridge the digital gaps, Indian leaders must specifically focus on developing and capitalizing on the following traits. McKinsey Report (2019) has highlighted the following traits of effective digital leaders:

Digital strategy Most leading companies use strategies that help them stand out to the customers and distinguish them from their competitors. They prioritize investing in new technologies that let them interact better with their customers. This investment is usually more than what their competitors choose to invest. Through the usage of e-commerce platforms, the chances of selling out are 2.3 times more likely than traditional means. These digital leaders are also better equipped to deal with digital disturbances as they adapt to uncertain environments easily. Their strategies are focused around the technology, letting it mould their modes of engagement rather than the other way around.

Digital organization Digital leaders prefer to have singular business units that operate and regulate digital strategies for the whole company. The companies classified as digital leaders often have senior executives that provide a reliable support system.

Digital capabilities “Digital leaders are digital adopters”, using digital tools more frequently than their competitors. They also utilize digital marketing as an important asset. Top companies are 2.6 times more likely to use customer management software as compared to their lower-ranking competitors and they are also more likely to organise their management systems by using planning systems by 2.5 times. Top companies as compared to lower-level companies are 2.3 times more inclined to use search optimisation and 2.7 times more willing to utilize social media to market their products.

10 Competencies of leaders in the digital world

The real problem that western firms face is their internal potential for the development of new business. Digital leadership can help expedite this process. Creating a new structure for value-creation is recommended. Ambition motivates leaders to bring about change. The aspirations need to transcend the present resources and how they are used. This leads to a need for resource leverage which can be achieved by developing a strategic framework that analyses the trends and how the industry is going to evolve, thus identifying central skills, competencies and products. Organizations, therefore, need to concentrate their time and energy into innovation (Prahalad 1993).

It is vital to consider the difference between competence and technology. While technology can stand-alone, competence is contingent on getting consistent and high yields. This exceeds design capabilities. As a process, converting designs into good results takes numerous functions. Thus, learning and understanding is essential and implied. Competence represents both implicit and explicit learning. A collective information base of these learnings that comprise a large population is essential to understanding core competencies (Prahalad 1993).

In many contexts, capabilities and competence are used synonymously. Capabilities are necessary for survival in an organisation. In contrast to a core competency, capabilities do not give organisations an upper hand over their competitors. Competence is a form of governance as well, controlling the various relationships within the business as well as the cumulative learning across the levels and functions of the organization. Competence = [Technology × Governance Process × collective learning] (Prahalad 1993).

According to the research by Korn Ferry Institute (2018), leaders in Asia are not ready to go digital yet and digital sustainability seems uncertain under the legacy of tried and tested ways. One cannot undermine the role leaders play in driving people to promote change. However, in order to move forward in this digital era, they must modify their ways to encourage the people, thus creating an open, active and well-connected culture to enhance performance.

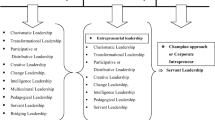

Using the Korn Ferry Four Dimensions of Leadership and the Korn Ferry Assessment of Leadership Potential, analysing the qualities of over 500 digital leaders and comparing them to their database, the researchers created a unique profile of what traits a leader needs for the digital era. Comparing this profile to more than 2600 leaders in India showed that in order to create a digital change that is sustainable and stable leaders need to adopt a drastic transformation in mindset (Korn Ferry Institute 2018) (Fig. 1).

Adapted from Korn Ferry Institute (2018), p. 2

Unique characteristics of high-performing digital leaders.

What makes a digital leader great is not just their ability to reach organizational goals but also fostering an environment that promotes future growth and success. Indian leaders are equipped to give desirable results and motivate people, however, their inclination towards structure limits their capabilities in uncertain circumstances. This also obstructs innovative thinking. This further encourages safer approaches, not leaving much space for taking risks, innovation and fostering entrepreneurial reasoning. Their comfort zone of certainty often makes it difficult for them to adjust to change. This restricts their ability to be flexible in a dynamic and uncertain digital environment. Breaking out of this comfort zone will assist them in developing a stronger insight into the digitized future and giving them the confidence to take more calculated risks. In order to shift the digital mindset, three important steps are recommended.

-

1

Prioritize In order to boost their confidence in uncertain situations, one needs to integrate a “fast-fail culture” by creating new opportunities. This will allow the leaders to make mistakes and learn from them, thus, increasing confidence.

-

2

Start recruiting and developing the mindset Developing a strategy that not only allows you to work with the current leaders but also invest in the future generations will help build a sustainable change. Building a system of assessments and profiles for the organization might help to maximize the engagement of both, leaders and their people, to contribute to the vision of the organisation.

-

3

Create and align symbols of change In India, a majority of the challenges arise due to cultural norms that are difficult to change. Therefore, creating new symbols of change that fit into the organisation's vision will help combat this. Opening up new channels of communication to dismantle the hierarchies, encouraging collaboration and hiring new employees as agents of change within the organization (Korn Ferry Institute 2018).

Indian leaders focus on creating a social mission that emphasises on transparency, enabling better communication and dismantling the hierarchy when it comes to decision making. This social mission helps in increasing employee engagement. They also focus more resources on training and develop systems that help them achieve the social mission. Leaders in the West can adapt this perspective through two easily achievable aims—more investments and making social missions stronger. Leaders in India tend to invest more in people and have long term goals that focus on internal growth than their counterparts. Even with the extensive job-hopping, they invest aggressively in training and development in order to increase commitment and openness (Cappelli et al. 2010).

One significant difference between Western and Indian leaders is the way they direct their energy. In the list of duties, Indian leaders prioritize their input for business strategies followed by being responsible for the organizational culture, being a guide for their employees and lastly, being a spokesperson of the owner's interests. According to surveys, for Indian leaders the strategy is of utmost importance, they play an integral role in forming the strategies for their organizations. By focusing less on the western ways of planning, they tend to spend more of their time on building incentives, organizational culture and structure. To them, a strategy is a set of policies for competing, like developing competencies and working towards a long-term goal. This helps build the companies competencies, embrace their social purpose as well as personalise the organizational culture. This improves the organization's agility in the market as well as allows them to train their top managers better. Therefore, the top two strategies are building a strategy and emphasis on guiding and coaching (Cappelli et al. 2010).

The reasoning behind investing so many resources in employee development is to make sure employees have the best tools to work with and all their requirements are met. This, in turn, ensures they remain committed to the organization for a long time. The prioritization of the development of their employees, forming their attitudes, maintaining the company culture and internationalization help ensure the same (Cappelli et al. 2010).

According to statistics, in the United States, new hires receive no form of training when they first get employed. In contrast, the Kauffman Foundation study showed that the Information Technology industry in India has a formal training program for new hires that lasts for 60 days. The Tata Consultancy Services has a seven-month program and even low-skill organisations usually have a month-long training program. Even with the high turnover rate of 30%, investing in training and development ensures the efficiency and quality of work in the organizations (Cappelli et al. 2010).

We live in very competitive times, where organizations are required to excel in many domains without compromising on quality, this includes being innovative and responsive to the consumers. Thus, the development of core competencies is integral and gives organizations an upper hand over their competitors. Creating newer strategies and assets at a lower cost than other companies and at a rapid pace gives these organizations an advantage for a longer period of time. Core competencies play a very important role, however, the number of competencies that one organization can develop is restricted. Therefore, the organization has to succeed in the competencies they choose to develop (Singh et al. 2008). In 2001, Chaston and their colleagues observed the domains that were concerned with organisational productivity, HR practices, quality management etc., and it showed that information management plays a crucial role in influencing the rate of growth in the company. Lei et al. (1999) (as cited in Singh et al. 2008) elucidate how efficiently organizations utilize new technology and information greatly influences their success.

Singh et al. (2008) put this in the Indian context, in their research on competencies and performance analysis, they used one-way Anova to identify competencies that are required to be improved in order to become ready for the future. How the developing competencies are prioritized has changed. Organization need to concentrate on areas such as market change identification, making effective decisions while using available information, and defining the quality standard based on the needs of the consumers, work environment optimization which is the highest-ranking priorities when it comes to developing competencies in the span if the next 3 years (Singh et al. 2008).

Looking at the Indian digitalization process through the lens of LMX theory and after analysing the digital gaps and competencies required to bridge the digital gap; taking into account the various suggestions put forth my researchers presented so far, personalities of Indian digital leaders must be fostered. A notion of “creative personalities” for leaders is put forth by Faix and Mergenthaler (2015). It is recommended that this notion be applied to the Indian digital leaders as well. Concept of personality operates on two levels—‘having a personality’ and ‘being a personality’. This two-fold approach of personality leads to the so-called “Schöpferische Persönlichkeit” simply translated from German into English as “creative personality”. An individual with a creative personality will ultimately function as a result of an amalgam of the spiritual elements of ‘having a personality’ and ‘being a personality’. The aspects of ‘having a personality’ show that it is a cumulation of five elements such as knowledge, competencies, temperament and character, identity, values and virtues. ‘Having a personality’ signifies an individual; who executes concrete actions. Each of the five elements depict a specific function namely the ability to act based on knowledge and competencies, the willingness to act (having a temperament) along with displaying behaviour that reflects intention, character, identity, values and virtues. Creative personalities have five components.

-

1

Creative personality and knowledge

Vast general knowledge is the crux for effective leadership. Being innovative is highlighted as a prime medium to success in leadership. In order to innovate one requires thinking on multiple levels. Catering to complex situations that is the real business situations requires such kind of multi-dimensional thinking and understanding. A leader is bound to have expert knowledge about for example technical terms, particular terminology, knowledge of technical methods and procedures, technical tools, knowledge about standards and legal framework etc. (Pirntke 2010). Conclusively, a creative personality must possess a sound technical entrepreneurial knowledge base.

-

2

Creative personality and competence

Only qualifications do not suffice when it comes to successful leadership. Qualifications usually considered as diplomas or certificates of a specific field are proof of demonstration of a certain set of skills in an organized and artificial situation. But creative personalities need to demonstrate something beyond qualifications. Creative personalities possess competencies that distinguish them from highly qualified individuals. Creative personalities display exceptional decision-making competency and the ability to take action. “They develop new knowledge to solve new problems (Prahalad and Krishnan 2009, p. 288) by bringing forth forward the new in a self-organized manner” (Faix and Mergenthaler 2015, p.138).

-

3

Creative personality, temperament and character

Temperament and character have their roots in human instinct. The character of a creative personality is recognized through the curiosity instinct and aggression instinct. Both these instincts play an important role in innovation which is a prerequisite of leadership. For creative personalities the result of being curious is pleasure, possess zest to discover and ably transform a possibility into reality by coming out of their comfort zone and fearlessly face the unknown situations (Horx 2009). The aggression instinct (a certain degree of aggressiveness) seems to be necessary for the creative personality as it is conceived as the drive to win, the drive for power, rank and recognition (Cube 1998, p. 12, as cited in Faix and Mergenthaler 2015).

-

4

Creative personality and identity

Identity of a creative personality can be clearly understood if he/she is realistic and self-critical, has a realistic estimation of one’s powers. A creative personality is able to cope with stress and other negative emotions such as anger and rage, keep calm, have patience, tolerance and manage one’s excitement, is optimally motivated and goal oriented has great social skills such as along with empathy, is able to handle psychological dependency on others and finally is capable of analyzing risks and dangers that come up from one’s own actions and actions of others. All the above-mentioned characteristics contribute positively to having a creative personality.

-

5

Creative personality, values and virtues

Successful leadership is impossible without innovation. To foster innovation in any organization, creative personalities must be nurtured. The values and virtues are exceptionally important as creative personalities ought to create something new and they must take the responsibility of the new and also must be capable of evaluating and foreseeing the risks associated with creating something new. Virtues that play an important role in innovation and subsequently in entrepreneurial success are reliability, prudence and mindfulness. Reliability means an individual acting, judging and deciding in an ingenuous manner objectively and subjectively. Prudence refers to acting, judging and deciding in a careful and far-sighted way. Mindfulness refers to acting, judging and deciding about other people and or objects with caution. Values essential for creative personalities are trust, tolerance, sustainability, consequence and respect. Trust “is the kind of faith in a person that becomes especially significant when the person one trusts must take action in a new or unprecedented situation” (Faix and Mergenthaler 2015, p. 143). Tolerance, as regarded by Bauman (1991) (as cited in Faix and Mergenthaler 2015) is the “otherness in the other”. It is expected that one does not act according to general rules and standards but only in a self-organized manner. Sustainability means “an effort to preserve and expand the social, environmental and economic prosperity of present and future generations” (Faix and Mergenthaler 2015, p. 143). Considering the global context, multicultural teams require mutual trust and respect for innovative thinking and action.

11 Future implications

The understanding of the traditional leadership culture in collectivistic countries like India would go a long way in planning the effective execution of digital leadership. The future focus of developing competencies for Indian digital leaders should be on building such creative personalities who can deal with challenging digital world with confidence, sound decision-making and readiness to adapt to changing digital times. In the context of knowledge, this would be especially important for senior leaders in terms of acquiring knowledge about and remaining up-to-date with the advancements in digital technology. As competencies exhibited by senior and emerging young employees would differ, training based on specific competencies aimed at respective age/experience of leaders could be planned. The aggressive temperament that form a component of creative personality can be interpreted as the authoritarian assertive drive to accomplish organization goals. The Indian traditional inclination towards high power distance and paternalistic leadership can be used in favour of building such creative leaders, while also maintaining the traditional sense of influencing members through a position of authority that is respected but not feared. The wisdom gained over time, the vast experience of dealing with myriad situations and challenges, and empathy towards employees as a parental figure leading them, can all create a favorable condition for garnering creative leadership as long as the blend of traditional values and modern attitudes come together in a smooth union. To summarize, it may be said that the challenges for LMX discussed earlier, can themselves become unique opportunities for building specific competencies among Indian leaders, provided that Western models aren’t applied directly without taking the cultural variables into consideration.

12 Limitations

The paper explores possible obstacles in the functioning of digital leadership in the Indian context and also explores few approaches in dealing with these challenges. These discussions however need to be understood in the light of certain limitations.

The first limitation is the digital divide. Paul (2002) refers to ‘digital divide’ as a disproportionate pace of development related to digital infrastructure, access and availability which is unique to every society. Digital divide results in variances across nations but also within nations for communities who are economically disadvantaged, or who belong to ethnic and linguistic minorities. Although India has recently been making encouraging efforts to bridge the gap by initiating a number of projects and programmes for inclusion of rural and remote locations, access to information and communication technology is still far from equal. This would translate into differential progress even in the training and creation of digital leaders. In keeping with the sociological theories related to digital divide, one can expect that leaders from the urban region and from higher socio-economic status would have had more opportunities to use digital technology and thus would consequently emerge as digital leaders much sooner compared to their counterparts hailing from rural areas and lower socio-economic status.

The second limitation which also impacts the digital divide is the age divide. Given the collectivistic culture, high power distance style of organizational interactions and prevalence of a favourable environment for paternalistic leadership, the current demographic cohort of Indian organizations may face certain challenges in embracing transformation in the form of digital leadership. The traditional leadership pattern demands a constant emphasis on personal yet paternal one-on-one interactions between the leader and the members, with the members expecting the leader to provide guidance and advice from a position of authority. The structure of most contemporary organizations in the country, however, is characterized by an age divide, with a young, dynamic and digitally fairly literate workforce being led in a traditional fashion, by a senior leader serving his/her final years in the said organization. This digital competency divide may cause the young members to experience a lack of connect with the leader in the highly informal virtual space and vice versa, the senior leaders may face difficulties in obtaining the necessary digital skill levels to communicate their mentorship to the young members. As traditional Indian leadership has relied heavily upon charismatic speeches by leaders and interpersonal bonding with the followers, this shift to a more virtual platform may render the digitization of organizational systems more complex. The challenge, therefore, arises not from the lack of necessary infrastructure, but rather from the attitudinal differences that appear to widen with the widening gap between traditional values and modern demands.

References

Anand S, Hu J, Liden RC, Vidyarthi PR (2011) Leader-member exchange: recent research findings and prospects for the future. The Sage Handbook of Leadership, Thousand Oaks, pp 311–325

Aryee S, Chen ZX (2006) Leader–member exchange in a Chinese context: antecedents, the mediating role of psychological empowerment and outcomes. J Bus Res 59(7):793–801

Aycan Z (2006) Paternalism: towards conceptual refinement and operationalization. In: Kim U, Yang KS, Hwang KK (eds) Indigenous and cultural psychology: understanding people in context. Springer, New York, NY, pp 445–466

Aycan Z, Kanungo RN, Mendonca M, Yu K, Deller J, Stahl G, Kurshid A (2000) Impact of culture on human resource management practices: a 10-country comparison. Appl Psychol Int Rev 49(1):192–221

Berghaus S, Back A (2016) Stages in digital business transformation: results of an empirical maturity study. Paper presented at the 10th Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems (MCIS 2016, Proceedings. 22.). Paphos, Cyprus. https://aisel.aisnet.org/mcis2016/22

Bharadwaj A, El Sawy OA, Pavlou PA, Venkatraman N (2013) Visions and voices on emerging challenges in digital business strategy. MIS Q 37(2):633–661. https://doi.org/10.25300/misq/2013/37.2.14

Bounfour A (2016) Digital futures, digital transformation, progress in IS. Springer International Publishing, Cham

Cappelli P, Singh H, Singh J, Useem M (2010) Leadership lessons from India. How the best Indian companies drive performance by investing in people. Harvard Business Review, Brighton

Chatterjee SR (2007) Human resource management in India: ‘Where From’ and ‘Where To?’. Res Pract Hum Resour Manag 15(2):92–103

Chhokar JS, Brodbeck FC, House RJ (eds) (2007) Culture and leadership across the world: the GLOBE book of in-depth studies of 25 societies. Routledge, Abingdon

Collin J, Hiekkanen K, Korhonen JJ, Halén M, Itälä T, Helenius M (2015) IT leadership in transition—The impact of digitalization on Finnish organizations. Research rapport, Aalto University, Department of Computer Science

Cortellazzo L, Bruni E, Zampieri R (2019) The role of leadership in a digitalized world: a review. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01938/full

Dickson D, Hargie O, Rainey S (2003) Cross-community communication and relationships in the workplace: a case study of a large Northern Ireland organisation. In: Hargie O, Dickson D (eds) Researching the troubles: social science perspectives on the Northern Ireland conflict. Mainstream Publishing, pp 183–2070

Erez M (1994) Towards a model of cross-cultural I/O psychology. Handb Ind Organ Psychol 4:569–607

Erpenbeck J, von Rosenstiel L (2003) Handbuch Kompetenzmessung. Erkennen, verstehen und bewerten von Kompetenzen in der betrieblichen, pädagogischen und psychologischen Praxis. Stuttgart

Fagerberg J, Godinho MM (2005) Innovation and catching-up. In: Fagerberg J, Mowery DC, Nelson RR (eds) The Oxford handbook of innovation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Faix WG, Mergenthaler J (2015) The creative power of education. On the formation of a creative personality as the fundamental condition for innovation and entrepreneurial success. Steinbeis-Edition. Translation of: Die schöpferische Kraft der Bildung, Steinbeis-Edition Stuttgart, 2010/2nd edn, 2013. https://www.steinbeis-sibe.de/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/SIBE_Schoepferische_Kraft_der_Bildung_web.pdf. Accessed 16 Oct 2019

Farh JL, Liang J, Chou LF, Cheng BS (2008) Paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations: research progress and future research directions. In: Chen CC, Lee YT (eds) Business leadership in China: philosophies, theories, and practices. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 171–205

Gelfand MJ, Bhawuk DPS, Nishii LH, Bechtold DJ, House RJ, Hanges PJ, Gupta V (2004) Culture, leadership, and organizations: the GLOBE study of 62 societies. Individualism and collectivism. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Gelfand MJ, Erez M, Aycan Z (2007) Cross-cultural organizational behavior. Ann Rev Psycholol 58:479–514

Hofstede G (2001) Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations, 2nd edn. Sage, London

Horx M (2009) Das Buch des Wandels. Wie Menschen Zukunft gestalten. DVA Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, München

House RJ, Hanges PJ, Javidan M, Dorfman PW, Gupta V (eds) (2004) Culture, leadership, and organizations: the GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage publications, Thousand Oaks

Kakar S (2008) Culture and psyche: selected essays. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Korn Ferry Institute (2018) Developing leaders for the digital age is mission-critical for organisational success. Digital leadership in India. https://focus.kornferry.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Korn-Ferry-Digital-leadership-in-India.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2019

Li F, Nucciarelli A, Roden S, Graham G (2016) How smart cities transform operations models: a new research agenda for operations management in the digital economy. Prod Plan Control 27(6):514–528

Maiti D, Castellacci F, Melchior A (2020) Digitalisation and development: issues for India and beyond. In: Maiti D, Castellacci F, Melchior A (eds) Digitalisation and development. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9996-1_1

Martinez PG (2005) Paternalism as a positive form of leadership in the Latin American context: leader benevolence, decision-making control and human resource management practices. Managing human resources in Latin America: An Agenda for International Leaders, pp 75–93

Mathur P, Aycan Z, Kanungo RN (1996) Indian organizational culture: a comparison between public and private sectors. Psychol Dev Soc 8(2):199–222

McKinsey Report (2019) Digital India: technology to transform a connected nation. McKinsey Global Institute. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/digital-india-technology-to-transform-a-connected-nation

Paul J (2002) Narrowing the digital Divide: Initiatives undertaken by the Association of south-east Asian Nations (ASEAN). Program Electron Lib Inf Syst 36(1):13–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/00330330210426085/full/html

Pellegrini E, Scandura T, Jayaraman V (2010) Cross-cultural generalizability of paternalistic leadership: an expansion of leader–member exchange theory. Group Organ Manag 35(4):391–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601110378456

Pirntke G (2010) Lernen nach der neuen Ausbildereignungsverordnung. Norderstedt

Prahalad CK (1993) The role of core competencies in the corporation. Res Technol Manag 36(6):40–47

Prahalad CK, Krishnan MS (2009) Die Revolution der Innovation. Wertschöpfung durch neue Formen in der globalen Zusammenarbeit, Munich

Rangarajan LN (ed) (1992) The Arthashastra. Penguin Books India

Reddy P (2018) A critical review on leadership in the digital age. Int J Acad Res Dev 3(1):467–468

Rockstuhl T, Dulebohn J, Ang S, Shore L (2012) Leader–member exchange (LMX) and culture: a meta-analysis of correlates of LMX across 23 countries. J Appl Psychol 97(6):1097–1130. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029978

Saffold GS III (1988) Culture traits, strength, and organizational performance: moving beyond “strong” culture. Acad Manag Rev 13(4):546–558

Sahyaja C, Rao KS (2018) New leadership in the digital era—a conceptual study on emotional dimensions in relation with intellectual dimensions. Int J Civ Eng Technol 9(1):738–747. https://www.iaeme.com/ijciet/issues.asp?JType=IJCIET&VType=9&IType=1

Seymour SC, Seymour SC (1999) Women, family, and child care in India: a world in transition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Shavitt S, Lalwani AK, Zhang J, Torelli CJ (2006) The horizontal/vertical distinction in cross-cultural consumer research. J Consum Psychol 16(4):325–342

Sihag BS (2004) Kautilya on the scope and methodology of accounting, organizational design and the role of ethics in ancient India. Account Hist J 31(2):125–148

Singh RK, Garg SK, Deshmukh S (2008) Competency and performance analysis of Indian SMEs and large organizations. Compet Rev 18(4):308–321. https://doi.org/10.1108/10595420810920798

Sinha JBP (1990) Work culture in Indian context. Sage, New Delhi

Sparrow PR, Budhwar PS (1997) Competition and change: mapping the Indian HRM recipe against world-wide patterns. J World Bus 32(3):224–242

Vogelsang M (2010) Digitalization in open economies: theory and policy implications. Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin

Westerman G, Bonnet D, McAfee A (2014) Leading digital: turning technology into business transformation. Harvard Business Review Press, Brighton

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms. Muskaan Malhotra, Third year Undergraduate, School of Liberal Education, FLAME University, Pune for her assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest. This article is not based on any study that required funding.

Rights and permissions

Open Access Dieser Artikel wird unter der Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz veröffentlicht, welche die Nutzung, Vervielfältigung, Bearbeitung, Verbreitung und Wiedergabe in jeglichem Medium und Format erlaubt, sofern Sie den/die ursprünglichen Autor(en) und die Quelle ordnungsgemäß nennen, einen Link zur Creative Commons Lizenz beifügen und angeben, ob Änderungen vorgenommen wurden. Die in diesem Artikel enthaltenen Bilder und sonstiges Drittmaterial unterliegen ebenfalls der genannten Creative Commons Lizenz, sofern sich aus der Abbildungslegende nichts anderes ergibt. Sofern das betreffende Material nicht unter der genannten Creative Commons Lizenz steht und die betreffende Handlung nicht nach gesetzlichen Vorschriften erlaubt ist, ist für die oben aufgeführten Weiterverwendungen des Materials die Einwilligung des jeweiligen Rechteinhabers einzuholen. Weitere Details zur Lizenz entnehmen Sie bitte der Lizenzinformation auf http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de.

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, S.S., Patki, S.M. Getting traditionally rooted Indian leadership to embrace digital leadership: challenges and way forward with reference to LMX. Leadersh Educ Personal Interdiscip J 2, 29–40 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1365/s42681-020-00013-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1365/s42681-020-00013-2