Abstract

Background

Numerous prediction models estimating the risk of complications after esophagectomy exist but are rarely used in practice. The aim of this study was to compare the clinical judgment of surgeons using these prediction models.

Methods

Patients with resectable esophageal cancer who underwent an esophagectomy were included in this prospective study. Prediction models for postoperative complications after esophagectomy were selected by a systematic literature search. Clinical judgment was given by three surgeons, indicating their estimated risk for postoperative complications in percentage categories. The best performing prediction model was compared with the judgment of the surgeons, using the net reclassification improvement (NRI), category-free NRI (cfNRI), and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) indexes.

Results

Overall, 159 patients were included between March 2019 and July 2021, of whom 88 patients (55%) developed a complication. The best performing prediction model showed an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.56. The three surgeons had an AUC of 0.53, 0.55, and 0.59, respectively, and all surgeons showed negative percentages of cfNRIevents and IDIevents, and positive percentages of cfNRInonevents and IDIevents. This indicates that in the group of patients with postoperative complications, the prediction model performed better, whereas in the group of patients without postoperative complications, the surgeons performed better. NRIoverall was 18% for one surgeon, while the remainder of the NRIoverall, cfNRIoverall and IDIoverall scores showed small differences between surgeons and the prediction models.

Conclusion

Prediction models tend to overestimate the risk of any complication, whereas surgeons tend to underestimate this risk. Overall, surgeons’ estimations differ between surgeons and vary between similar to slightly better than the prediction models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer in the world and the sixth leading cause of death from cancer.1 In recent years, the introduction of neoadjuvant therapy has contributed to a better survival, and minimally invasive esophageal surgery has led to lower postoperative morbidity.2,3,4 Although postoperative mortality has decreased in the last 30 years, esophageal surgery remains a highly invasive procedure, with reported complication rates of up to 74%.5,6,7 Postoperative complications are associated with postoperative mortality, length of hospital stay, readmission rate, early cancer recurrence, long-term survival, and health-related quality of life.8,9,10,11,12 A clear understanding of the relationship between various risk factors and postoperative complications would enhance selection, counseling, and, if possible, preoperatively improve patients’ status.

Thus far, numerous prediction models have been proposed to estimate the risk of specific complications after esophagectomy;13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 however, these models are not commonly used in practice and surgeons generally rely on their own clinical judgment. Hence, it remains unclear whether these existing prediction models have a higher predictive power in estimating postoperative outcome than surgeons’ judgment.

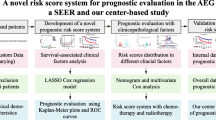

The primary aim of this study was to assess whether the available prediction models are superior to the clinical judgment of the surgeon with regard to predicting the risk of any postoperative complication, while the secondary outcome was to assess how well surgeons can predict major (Clavien–Dindo grade IIIA or higher) postoperative complications.

Methods

Study Design

A prospective, single center, observational cohort study was conducted at a tertiary referral hospital (Amsterdam UMC). Ethical approval was waived by the Ethical Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in this study for use of their patient data. The TRIPOD and STROBE guidelines were consulted to ensure the correct reporting of the results.24,25

Study Population

Eligible patients were aged 18 years or older with resectable esophageal or gastroesophageal junction carcinoma (cT0-4aN0-3M0), and scheduled to undergo a minimally invasive transthoracic esophageal resection by one of the three surgeons. Patients were excluded in cases of a salvage esophagectomy, an esophagectomy for recurrent disease, or if nonresectable disease was found during esophagectomy.

Treatment of Patients

All patients were treated according to the Dutch guideline.26 Patients were generally treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by a minimally invasive transthoracic esophagectomy with a two-field lymphadenectomy. A gastric conduit reconstruction was performed with a cervical or intrathoracic anastomosis, depending on tumor characteristics and the extent of the radiotherapy field.

Selection of Prediction Models from the Literature

A systematic search of the available literature in the PubMed and Embase databases was performed in order to identify relevant studies describing prediction models for postoperative complications after esophageal surgery; the search strategy is described in electronic supplementary Table SDC1. Studies were eligible if they described the establishment of a prediction model that predicts the occurrence of postoperative complications after an esophageal resection with gastric conduit reconstruction; however, studies were excluded if they only described a prediction model that predicts specific (i.e. only pulmonary complications) complications or only mortality after esophageal surgery.

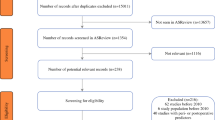

The literature search resulted in 123 studies. Two prediction models, one by Reeh et al. (the Preoperative Esophagectomy Risk [PER] score) and one by Lagarde et al., were identified as predictors of the risk of postoperative complications after esophagectomy.14,27 A flow chart of the literature search is shown in Fig. 1. A description of the included prediction models and performance of the prediction models is shown in electronic supplementary Table SDC3.

Clinical Judgment of the Surgeon

Three surgeons (IvBH, SSG, and WJE) were asked to estimate the probability of a consecutive series of patients to develop a postoperative complication (any complication and a major complication, i.e., Clavien–Dindo grade IIIA or higher). Surgeon 1 had 14 years of experience, whereas surgeons 2 and 3 had 9 and 2 years of experience, respectively. All surgeons were blinded from the other surgeons’ response and outcome of the prediction models. One day prior to surgery, surgeons completed the Preoperative Risk Score Form (electronic supplementary Table SDC4) after studying the patient file and clinically evaluating the patient, regardless if they were operating themselves or not. The surgeons were not blinded from who was the operating surgeon. On this form, the surgeons could indicate their estimation on a 10-point scale with percentage categories for the patients to develop any or a major complication (Clavien–Dindo grade IIIA).

Study Outcomes

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the discriminative ability of the existing prediction models compared with the accuracy of the clinical judgment of the surgeon with regard to predicting the risk of any postoperative complication, while secondary outcomes were the performance of the selected prediction models in this cohort, the performance of the surgeons, and to describe how well surgeons can predict major (Clavien–Dindo grade IIIA or higher) postoperative complications. Complications were identified and collected until 30 days post-surgery and graded according to the classification by the Esophageal Complications Consensus Group (ECCG) and the Clavien–Dindo classification.28,29

Reclassification Measures

Reclassification measures were used to describe the difference between the ability of the surgeon and prediction models to predict postoperative complications.

Comparing the area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUCs) is the most common strategy to compare prediction models;30 however, comparing AUCs has proven to be insensitive to important changes in absolute risk.31 Therefore, reclassification measures are recommended. Using these models, patients are stratified into clinical categories based on risk in the first (reference) model, then the ability of the second (the surgeon) to more accurately reclassify individuals into higher or lower risk strata is quantified.32,33 Three reclassification measures were used in the current study: the net reclassification improvement (NRI), category-free NRI (cfNRI), and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) indexes.

The NRI attempts to quantify how well a second model (in this case the surgeon) reclassifies subjects to a more appropriate risk category. The overall NRI is the sum of NRIevents and NRInonevents. NRI ranges from −1 to 1, where 0 indicates no difference. An NRI closer to 1 correlates with a better prediction of the second model (the surgeons) and an NRI closer to −1 correlates with a better prediction by the first model. The NRI requires a threshold in risk score in order to be able to categorize patients. In this study, a threshold of 60% was chosen since the incidence of complications after esophagectomy is reported to be around 60% in Dutch centers.34,35 A probability of over 60% represents an increased risk. The cfNRI counts the direction of change for every individual instead of the crossing from a higher-risk group to a lower-risk group and vice versa. cfNRI values above 60% should be interpreted as a strong improvement in comparison with the reference model; those around 40% should be considered intermediate improvement and those below 20% should be considered weak improvement.36 Finally, IDI counts the actual change in calculated risk for each subject instead of only the direction of change, as the cfNRI does. A higher IDI correlates with better estimation by the surgeon and a negative IDI indicates a better prediction by the prediction model.

Sample Size Calculation

To calculate the number of patients necessary for this study, the number of patients needed to develop a prediction model was used. This calculation was based on the number of degrees of freedom in the largest prediction model is this study, i.e. the study by Lagarde et al. This model includes six variables (either dichotomous or continuous). It is desirable to include a representative sample with at least 10 events and 10 nonevents per variable. Since more than half of the patients usually develop a complication, at least 60 patients without a complication were needed.37 Internationally, the incidence of patients with one or more postoperative complications after an esophageal resection for surgery is 60%.34 Therefore, the total sample size was set at 150 patients.

Statistical Analysis

All risk factors included in the prediction models are displayed in the baseline table. To compare categorical data, the Pearson Chi-square test or Fishers exact test were used, as appropriate. The independent samples t-test was used for continuous data with normal distribution. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous data with non-normal distribution.

The performance of the prediction models was estimated in the current dataset. For each surgeon and prediction model, the calibration (the ability to quantify the observed absolute risk) and discrimination (ability to discriminate between patients with and without an event) were described. Discrimination was examined with the AUC, and calibration was examined with the observed/expected ratio and calibration intercept and slope.

Based on calibration and discrimination, the best performing model was chosen and then compared with the clinical judgment of the surgeons using reclassification measures (NRI, cfNRI, and IDI) in addition to quantifying the difference between AUCs. Missing data were handled with single imputation. All p-values were based on a two-sided test and a p-value <0.050 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS for windows, version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 3.3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 208 patients underwent esophagectomy between March 2019 and July 2021. A total of 49 patients were excluded: 18 patients because none of the surgeons had estimated the postoperative complication risk, 17 patients underwent salvage esophagectomy, 5 were intraoperatively found to have nonresectable disease, and 9 underwent an open esophagectomy. Therefore, in total 159 patients were included in the present study. Overall, 88 of 159 patients (55%) developed postoperative complications within the first 30 days. Of those, 48 patients (55%) developed a minor complication (Clavien–Dindo lower than grade III), whereas 40 patients (45%) developed a major complication (Clavien–Dindo grade IIIA or higher). Clinicopathological characteristics were comparable between patients with and without complications (Table 1). Table 2 shows the incidence of specific postoperative complications and severity.

Performance of Prediction Models

Of the 106 patients with a PER score classified as ‘low risk’ by Reeh et al., 56 (52%) developed a complication; of the 35 patients with a PER score of ‘medium risk’, 20 (57%) developed a complication; and of the 18 patients with a PER score of ‘high risk’, 12 patients (67%) developed a complication. Median PER scores for patients with and without complications are shown in Table 3.

Using the model by Lagarde and colleagues, patients who did not develop complications had a median score of 22 (interquartile range [IQR] 19–25), and those who did develop complications had a median score of 23 (IQR 20–26) (Table 3). The performance of both models to predict any complication are displayed in Table 4. The prediction model by Lagarde et al. had better performance and was therefore compared with the risk estimation by the surgeons.

Risk Estimation by the Surgeons

Risk estimations were made by three surgeons using the preoperative form for risk assessment. For surgeon 1, patients with a complication had a median risk score of 55% (IQR 25–65%) and patients without a complication had a median risk score of 45% (IQR 5–55%); for surgeon 2, patients with and without complications had a median risk score of 55% (IQR 35–75%) and 55% (IQR 35–75%), respectively; and for surgeon 3, patients with and without complications had a median risk score of 65% (IQR 45–65%) and 55% (IQR 35–65), respectively (Table 3). The discriminative ability and calibration measures for each surgeon are displayed in Table 4.

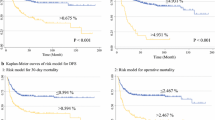

Comparison of the Prediction Model and Risk Estimation by the Surgeon in Predicting Any Complication

Surgeons 1 and 2 had a lower AUC and surgeon 3 had a higher AUC than the prediction model by Lagarde et al., although these differences were small and were not statistically significant (Table 5). The observed/expected ratio was 0.69 for the model by Lagarde et al., indicating an overestimation of the risk of complications, whereas the observed/expected ratios for the surgeons where all >1, indicating an underestimation of the risk of complications (Table 4).

This was reflected in negative NRIevents, cfNRIevents and IDIevents scores and positive NRInonevents, cfNRInonevents and IDInonevents scores (Table 5).

Overall, the NRI for surgeons 1, 2, and 3 were −8%, 1%, and 18%, respectively, indicating improvement for surgeon 3 compared with the prediction model, and a similar estimation compared with the model for surgeons 1 and 2. The cfNRI showed no improvement in the estimation from all surgeons (−6%, −3%, and 0% for surgeons 1, 2, and 3, respectively). The IDI showed small differences between the surgeons and the prediction model (−3%, 1%, and 1%, respectively). All reclassification measures are detailed in Table 5.

Risk Estimation by the Surgeon in Predicting Major (Clavien–Dindo Grade IIIA or Higher) Complications

The median estimated risk for patients with a major postoperative complication by surgeons 1, 2, and 3 was 35% (IQR 15–35%), 15% (5–35%), and 45% (35–55%), respectively, and 25% (15–35%), 15% (5–35%), and 35% (18–55%) for patients without major postoperative complications. Discrimination and calibration are shown in Table 6.

Discussion

Risk stratification has been a hot topic in esophageal cancer surgery for many years. We investigated whether available prediction models are superior compared with the clinical judgment of the surgeon with regard to predicting the risk of postoperative complications after esophagectomy. Surgeons 1 and 2 performed similar to the prediction models and surgeon 3 performed slightly better. Moreover, the prediction models tended to overestimate the risk of any complication, whereas all surgeons tended to underestimate the risk of any complication. When estimating the risk for major complications (Clavien–Dindo grade IIIA or higher), three surgeons had an AUC of around 0.5 and poor calibration. It is of clinical relevance to identify high-risk patients in order to improve informing about their risks for complication. High-risk patients could be monitored more thoroughly postoperatively and perhaps a lower threshold for postoperative diagnostics or treatment would be justified. To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating prediction models in comparison with the clinical judgment of specialized surgeons with regard to predicting the risk of postoperative complications after esophagectomy.

The performance of the model by Reeh and colleagues differed considerably between the current study and the original study.14 The poor predictive performance could be explained by the differences in patient groups and treatment characteristics between both cohorts. Almost all patients in the current study received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy, whereas none of the patients in the study by Reeh et al. were treated neoadjuvantly. Moreover, every patient in the current study underwent a transthoracic esophagectomy versus less than half of the patients in the development cohort. Neoadjuvant therapy and a transthoracic approach can both negatively affect postoperative outcomes.38,39

Our results differ from the model proposed by Lagarde et al. regarding performance measures. We found an AUC of 0.56, whereas Lagarde et al. reported an AUC of 0.65 in their test cohort and 0.64 in the external validation cohort.40 Patients in the study by Lagarde et al. were all operated by the open approach and were not treated with neoadjuvant therapy, whereas in the current study, all patients were treated by a minimally invasive procedure and treated neoadjuvantly. These differences between the developmental cohort and the current study cohort might explain the differences in performance.

Clinical judgment, considering comorbidities, preoperative tests, and an estimation of a patient’s ability to withstand the physical damage of surgery, are all essential in patient selection for esophagectomy. Multiple studies have demonstrated that the surgeons’ clinical assessment is a good predictor of postoperative complications in major gastrointestinal surgery and is even more accurate than the POSSUM score.41,42 Our results revealed heterogeneity between the surgeons’ clinical judgment. All surgeons underestimated the risk of complications, which is also seen in another study evaluating surgeons’ assessment in different types of surgery.43 One surgeon had an acceptable AUC of 0.59, whereas others performed poorly, with an AUC ranging from 0.53 to 0.59. The lack of agreement could be explained by different factors on which surgeons base their clinical judgment or the difference in years of experience, since the most experienced surgeon had the best AUC.

Of all patients, 25% developed a major complication. Surgeons 1 and 3 performed better than surgeon 2 in predicting major complications, with an AUC of 0.59, and higher median risk scores for patients with major complications compared with patients without. Calibration also varied widely between surgeons, yet all surgeons had poor calibration measures. No other studies have compared surgeons’ assessment with prediction models in assessing major complications after esophagectomy. D'Journo et al. developed and validated a risk prediction model of death within 90 days after esophagectomy.44 This model showed good discriminative ability, with an AUC of 0.64 in the validation cohort. Future studies could compare surgeons’ assessment with this model or develop a new prediction model specifically focusing on major complications.

All surgeons had negative NRIevents, cfNRIevents and IDIevents, and positive NRInonevents, cfNRInonevents and NRInonevents percentages. This indicates that surgeons underestimate the risk of a complication compared with the prediction model. The overall NRI percentage was similar to 0 for surgeons 1 and 2, and significantly positive for surgeon 3, indicating that only surgeon 3 was better at predicting overall complications than the prediction model, when utilizing a threshold of 60% risk. However, when comparing the surgeons with the prediction model without a threshold (cfNRI), one surgeon showed a weak improvement and two surgeons showed a small diminishment. When quantifying the improvement of reclassification by surgeons compared with the prediction models, the IDI scores were positive for two surgeons and negative for one surgeon, but all were close to 0%. Thus, surgeons perform similar to the prediction model in predicting overall complications based on IDI and cfNRI. To date, no studies exist that evaluate the clinical judgment of surgeons in predicting postoperative morbidity after esophagectomy to compare our results with. However, a systematic review assessing the accuracy with which surgeons can predict outcomes following many different types of surgery, including gastrointestinal, found that the surgeons' prediction of general morbidity was good and was equivalent to or better than pre-existing prediction models.45

Evaluating the relationship between experience and accuracy in predicting complications showed that surgeon 3, the most experienced surgeon, had a higher median risk score for patients with complications, the highest AUC, and overall better calibration measures compared with surgeons 2 and 3. Surgeon 3 with the least experience has less favorable outcomes than surgeon 2. These data show that there is a trend of surgeons with more experience in predicting complications more accurately than less experienced surgeons, although no statistical tests could be performed reliably due to the low number of participants. These results are in line with another study that showed that senior surgeons were superior in predicting outcomes.46

The present study has some limitations. First, there were few prediction models designed specifically for predicting postoperative complications after esophagectomy. Furthermore, our single-institution study provides less generalizable results. Moreover, most of these models were constructed before the implementation of minimally invasive transthoracic surgery and/or neoadjuvant therapy, which makes these models less generalizable to current practice. This also indicates that there is a need for an up-to-date prediction model. Furthermore, surgeons were not able to be blinded as to who the operating surgeon was since this team of surgeons always operates together and the scores were completed 1 day before the actual surgery. Additionally, the 10-point scale for the surgeons to indicate their estimated risk for a patient to develop a postoperative complication is a nonvalidated tool and was chosen because it is straightforward but still enables reclassification. However, this form can feel counterintuitive to some who would prefer a dichotomous scale or a visual analogue scale. The risk of complications should be weighed against the ‘risk’ of a complete pathological response, in which case surgery could be omitted. In this study, complication and pathological complete response (pCR) rates were 25% and 26%, respectively. Unfortunately, it is still not possible to reliably predict a cPR, as 60% of patients in a recent study still had vital tumor even though the clinical response evaluation was negative.47 Perhaps in the future, with the evolving of (imaging) techniques, this rate will improve and patients can be safely offered active surveillance.

This study has found that generally, surgeons underestimate the risk of complications and the prediction models overestimate the risk of complications. When comparing both, two surgeons predicted complications similar to the prediction model and one surgeon predicted complications slightly better than the prediction model. The surgeon’s assessment is therefore important when counseling patients about the risks of esophageal surgery in addition to prediction models. However, there was a large heterogeneity between the risk estimations between surgeons. This implicates that both prediction models and the clinical judgment of the surgeons are equally useful, and possibly combining both might lead to the best risk assessment. Discussing patients in multidisciplinary teams with multiple surgeons and other specialists might benefit the risk estimation of the surgeon. One study evaluating the ability of the surgeon to predict complications among different types of surgery incorporated the surgeons’ assessment in a previously developed multifactorial model and found an improved discriminative ability.43 More so, evidence suggests that exposure to pre‐existing prediction models leads to less varied and more accurate judgments of operative risk among surgeons and thus should be used in tandem with their gut feeling.45,48 Therefore, further studies could validate our findings and incorporate surgeons’ assessment in prediction models, or combine prediction models specifically for esophageal surgery with the clinical judgment of the surgeon. Given the finding that surgeons generally underestimated the risk of postoperative complications, it would be valuable to assess if providing feedback to the surgeons would help improve their estimation. Another interesting endpoint could be if the clinical judgment of the surgeon directly after surgery (incorporating blood loss, quality of the gastric conduit) changes their estimation. This does not facilitate the possibility to better inform patients about the risk of complications, but has the benefit of identifying high-risk patients. In addition, since major complications result in more postoperative mortality and decreased quality of life, future studies should therefore not only focus on predicting any complication but also on predicting major complications. We aim to conduct a follow-up study developing a new prediction model that takes into account the current treatment of neoadjuvant therapy and minimally invasive surgery. We will consecutively analyze if incorporation of the estimation by the surgeon would benefit this model. One of the endpoints in this follow-up study would be the inter-surgeon variability in predictions, and also to identify factors that contribute to a correct prediction by surgeons.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that surgeons’ assessment differs between surgeons and varies between similar to slightly better than the prediction models in predicting the risk of postoperative complications after esophageal cancer surgery. Prediction models could be used in tandem with surgeons’ own risk estimation. Future studies are required in order to assess the benefit of incorporating the surgeon’s assessment in prediction models to reach a higher level of predicting outcomes in this patient group with high chances of postoperative complications.

References

Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. Lyon. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. acedido em 28/04/2016. Available at: http//globocan.iarc.fr. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2013.01.011

Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, et al. Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: An updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70142-5.

Luketich JD, Pennathur A, Awais O, et al. Outcomes after minimally invasive esophagectomy: Review of over 1000 patients. Ann Surg. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182590603.

Mariette C, Meunier B, Pezet D, et al. Hybrid minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: A multicenter, open-label, randomized phase III controlled trial, the MIRO trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.33.3_suppl.5.

Dunst CM, Swanstrom LL. Minimally invasive esophagectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(Suppl 1):S108–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-009-1029-x.

Courrech Staal EFW, Aleman BMP, Boot H, Van Velthuysen MLF, Van Tinteren H, Van Sandick JW. Systematic review of the benefits and risks of neoadjuvant chemoradiation for oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7175.

Low DE, Alderson D, Cecconello I, et al. International consensus on standardization of data collection for complications associated with esophagectomy: Esophagectomy Complications Consensus Group (ECCG). Ann Surg. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001098.

Lerut T, Moons J, Coosemans W, et al. Postoperative complications after transthoracic esophagectomy for cancer of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction are correlated with early cancer recurrence: Role of systematic grading of complications using the modified clavien classification. Ann Surg. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bdd5a8.

Rizk NP, Bach PB, Schrag D, et al. The impact of complications on outcomes after resection for esophageal and gastroesophageal junction carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.08.007.

Kassin MT, Owen RM, Perez SD, et al. Risk factors for 30-day hospital readmission among general surgery patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.05.024.

Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, Mosca C, Healey NA, Kumbhani DJ. Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Annals of Surgery. ; 2005. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000179621.33268.83

Derogar M, Orsini N, Sadr-Azodi O, Lagergren P. Influence of major postoperative complications on health-related quality of life among long-term survivors of esophageal cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3568.

D’Journo XB, Berbis J, Jougon J, et al. External validation of a risk score in the prediction of the mortality after esophagectomy for cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/dote.12447.

Reeh M, Metze J, Uzunoglu FG, et al. The per (preoperative esophagectomy risk) score: A simple risk score to predict short-term and long-term outcome in patients with surgically treated esophageal cancer. Med (United States). 2016 Feb;95(7):e2724. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002724

Fuchs HF, Harnsberger CR, Broderick RC, et al. Simple preoperative risk scale accurately predicts perioperative mortality following esophagectomy for malignancy. Dis Esophagus. 2017. Jan;30(1):1-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dote.12451

Ferguson MK, Celauro AD, Prachand V. Prediction of major pulmonary complications after esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91(5):1494–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.12.036.

Xing X. Assessment of a predictive score for pulmonary complications in cancer patients after esophagectomy. World J Emerg Med. 2016;7(1):44–9. https://doi.org/10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2016.01.008.

Matthew Reinersman J, Allen MS, Deschamps C, et al. External validation of the Ferguson pulmonary risk score for predicting major pulmonary complications after oesophagectomy. Eur J Cardio-thoracic Surg. 2016;49(1):333–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezv021.

Takeuchi H, Miyata H, Gotoh M, et al. A risk model for esophagectomy using data of 5354 patients included in a Japanese nationwide web-based database. Ann Surg. 2014;260(2):259–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000644.

Hodari A, Hammoud ZT, Borgi JF, Tsiouris A, Rubinfeld IS. Assessment of morbidity and mortality after esophagectomy using a modified frailty index. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.051.

Dutta S, Al-Mrabt NM, Fullarton GM, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. A comparison of POSSUM and GPS models in the prediction of post-operative outcome in patients undergoing oesophago-gastric cancer resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(10):2808–17. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-011-1676-5.

Lagarde SM, De Boer JD, Ten Kate FJW, Busch ORC, Obertop H, Van Lanschot JJB. Postoperative complications after esophagectomy for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus are related to timing of death due to recurrence. Ann Surg. 2008;247(1):71–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815b695e.

Schröder W, Bollschweiler E, Kossow C, Hölscher AH. Preoperative risk analysis - A reliable predictor of postoperative outcome after transthoracic esophagectomy? Langenbeck’s Arch Surg. 2006;391(5):455–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-006-0067-z.

Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KGM. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD statement. Eur Urol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.11.025.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):1623–7. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296.

Nederlandse Vereniging van Maag-Darm-Leverartsen. Richtlijn Oesofaguscarcinoom. Versie: 3.1. 2015. Available at: https://www.oncoline.nl/oesofaguscarcinoom. Accessed 3 May 2019.

Lagarde SM, Reitsma JB, Maris AKD, et al. Preoperative prediction of the occurrence and severity of complications after esophagectomy for cancer with use of a nomogram. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.03.014.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae.

Low DE, Kuppusamy MK, Alderson D, et al. Benchmarking complications associated with esophagectomy. Ann Surg. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002611.

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747.

Harrell FE Jr. Multivariable Modeling Strategies. In: Harrell FE Jr (ed). Regression Modeling Strategies; Springer; 2015. pp. 63–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19425-7_4

Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.672402.

Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2929.

Dutch Institute for Clinical Auditing. DICA Jaarrapportage. Dutch Institute for Clinical Auditing; 2018.

Dutch Institute for Clinical Auditing. DICA Jaarrapportage. Dutch Institute for Clinical Auditing; 2017.

Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4085.

Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2001. p. 608.

Reynolds JV, Ravi N, Hollywood D, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation may increase the risk of respiratory complications and sepsis after transthoracic esophagectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.05.015.

Boshier PR, Anderson O, Hanna GB. Transthoracic versus transhiatal esophagectomy for the treatment of esophagogastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2011;254(6):894–906. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182263781.

Grotenhuis BA, Van Hagen P, Reitsma JB, et al. Validation of a nomogram predicting complications after esophagectomy for cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(3):920–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ATHORACSUR.2010.06.024.

Pettigrew RA, Hill GL. Indicators of surgical risk and clinical judgement. Br J Surg. 1986. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800730121.

Markus PM, Martell J, Leister I, Horstmann O, Brinker J, Becker H. Predicting postoperative morbidity by clinical assessment. Br J Surg. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.4608.

Woodfield JC, Pettigrew RA, Plank LD, Landmann M, Van Rij AM. Accuracy of the surgeons’ clinical prediction of perioperative complications using a visual analog scale. World J Surg. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-007-9178-0.

D’Journo XB, Boulate D, Fourdrain A, et al. Risk prediction model of 90-day mortality after esophagectomy for cancer. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(9):836–45. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2021.2376.

Dilaver NM, Gwilym BL, Preece R, Twine CP, Bosanquet DC. Systematic review and narrative synthesis of surgeons’ perception of postoperative outcomes and risk. BJS Open. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs5.50233.

van de Graaf VA, Bloembergen CH, Willigenburg NW, et al. Can even experienced orthopaedic surgeons predict who will benefit from surgery when patients present with degenerative meniscal tears? A survey of 194 orthopaedic surgeons who made 3880 predictions. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(6):354 LP - 359. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100567

Noordman BJ, Spaander MCW, Valkema R, et al. Detection of residual disease after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for oesophageal cancer (preSANO): a prospective multicentre, diagnostic cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(7 Suppl):965–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30201-8.

Sacks GD, Dawes AJ, Ettner SL, et al. Impact of a risk calculator on risk perception and surgical decision making: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001750.

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

No sources of support such as grants, equipment, and drugs were granted for this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hagens, E.R.C., Cui, N., van Dieren, S. et al. Preoperative Risk Stratification in Esophageal Cancer Surgery: Comparing Risk Models with the Clinical Judgment of the Surgeon. Ann Surg Oncol 30, 5159–5169 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-023-13473-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-023-13473-9