Abstract

Introduction

While social determinants of health may adversely affect various populations, the impact of residential segregation on surgical outcomes remains poorly defined.

Objective

The objective of the current study was to examine the association between residential segregation and the likelihood to achieve a textbook outcome (TO) following cancer surgery.

Methods

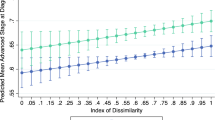

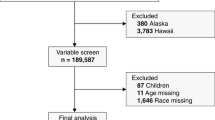

The Medicare 100% Standard Analytic Files were reviewed to identify Medicare beneficiaries who underwent resection of lung, esophageal, colon, or rectal cancer between 2013 and 2017. Shannon’s integration index, a measure of residential segregation, was calculated at the county level and its impact on composite TO [no complications, no prolonged length of stay (LOS), no 90-day readmission, and no 90-day mortality] was examined.

Results

Among 200,509 patients who underwent cancer resection, the overall incidence of TO was 56.0%. The unadjusted likelihood of achieving a TO was lower among patients in low integration areas [low integration: n = 19,978 (55.0%) vs. high integration: n = 18,953 (59.3%); p < 0.001]. On multivariable analysis, patients residing in low integration areas had higher odds of complications [odds ratio (OR) 1.07, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03–1.11], extended LOS (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.09–1.18), and 90-day mortality (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.22–1.38) and, in turn, lower odds of achieving a TO (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.84–0.90) versus patients from highly integrated communities.

Conclusion

Patients who resided in counties with a lower integration index were less likely to have an optimal TO following resection of cancer compared with patients who resided in more integrated counties. The data highlight the importance of increasing residential racial diversity and integration as a means to improve patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–66.

Graham GN. Why your ZIP code matters more than your genetic code: promoting healthy outcomes from mother to child. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11:396–7.

Meyer OL, Castro-Schilo L, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Determinants of mental health and self-rated health: a model of socioeconomic status, neighborhood safety, and physical activity. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1734–41.

Puckrein GA, Egan BM, Howard G. Social and medical determinants of cardiometabolic health: the big picture. Ethn Dis. 2015;25(4):521–4.

Bennett KM, Scarborough JE, Pappas TN, et al. Patient socioeconomic status is an independent predictor of operative mortality. Ann Surg 2010; 252(3):552–7; discussion 557–8.

Semega J, Kollar M, Shrider EA, Creamer JF. Income and poverty in the United States: 2019. Current Population Reports. Washington DC: United States Census Buruea; 2020. pp. 60–270.

Rangrass G, Ghaferi AA, Dimick JB. Explaining racial disparities in outcomes after cardiac surgery: the role of hospital quality. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(3):223–7.

Nathan H, Frederick W, Choti MA, et al. Racial disparity in surgical mortality after major hepatectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(3):312–9.

Popescu I, Duffy E, Mendelsohn J, et al. Racial residential segregation, socioeconomic disparities, and the White-Black survival gap. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0193222.

Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404–16.

Landrine H, Corral I, Lee JGL, et al. Residential Segregation and Racial Cancer Disparities: A Systematic Review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(6):1195–205.

Kershaw KN, Pender AE. Racial/ethnic residential segregation, obesity, and diabetes mellitus. Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16(11):108.

Diaz A, Chavarin D, Paredes AZ, et al. Association of neighborhood characteristics with utilization of high-volume hospitals among patients undergoing high-risk cancer surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(2):617–31.

Lucas FL, Stukel TA, Morris AM, et al. Race and surgical mortality in the United States. Ann Surg. 2006;243(2):281–6.

Allen JG, Weiss ES, Arnaoutakis GJ, et al. The impact of race on survival after heart transplantation: an analysis of more than 20,000 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2010; 89(6):1956–63; discussion 1963–4.

Trivedi AN, Sequist TD, Ayanian JZ. Impact of hospital volume on racial disparities in cardiovascular procedure mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(2):417–24.

Godley PA, Schenck AP, Amamoo MA, et al. Racial differences in mortality among Medicare recipients after treatment for localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(22):1702–10.

Mehta R, Paredes AZ, Tsilimigras DI, et al. Influence of hospital teaching status on the chance to achieve a textbook outcome after hepatopancreatic surgery for cancer among Medicare beneficiaries. Surgery. 2020;168(1):92–100.

Tsilimigras DI, Mehta R, Merath K, et al. Hospital variation in Textbook Outcomes following curative-intent resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: an international multi-institutional analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2020;22(9):1305–13.

Heidsma CM, Hyer M, Tsilimigras DI, et al. Incidence and impact of Textbook Outcome among patients undergoing resection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: results of the US Neuroendocrine Tumor Study Group. J Surg Oncol. 2020;121(8):1201–8.

Shwartz M, Restuccia JD, Rosen AK. Composite measures of health care provider performance: a description of approaches. Milbank Q. 2015;93(4):788–825.

Kolfschoten NE, Kievit J, Gooiker GA, et al. Focusing on desired outcomes of care after colon cancer resections; hospital variations in ‘textbook outcome.’ Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39(2):156–63.

Shannon C. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Techn J. 1948;27(379–423):623–56.

Reardon S, O’Sullivan D. Measures of spatial segregation. Sociol Methodol. 2004;34:121–62.

Schilling M. Measuring diversity in the United States. Math Horizons. 2002;9(4):29–30.

Morris EK, Caruso T, Buscot F, et al. Choosing and using diversity indices: insights for ecological applications from the German Biodiversity Exploratories. Ecol Evol. 2014;4(18):3514–24.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Limited Data Set (LDS) Files 06/30/2020 11:06 AM. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Files-for-Order/Data-Disclosures-Data-Agreements/DUA_-_NewLDS. Accessed 23 Feb 2021.

Manson S, Schroeder J, Van Riper D et al. IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 15.0.

Bureau USC. Housing patterns. Appendix B: measures of residential segregation. Available at: https://www.census.gov/topics/housing/housing-patterns/guidance/appendix-b.html. Accessed 29 Oct 2020.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–82.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–9.

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. CDC Social Vulnerability Index September 15, 2020, Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html. Accessed 27 Nov 2020.

Merath K, Chen Q, Bagante F, et al. Textbook outcomes among medicare patients undergoing hepatopancreatic surgery. Ann Surg. 2020;271(6):1116–23.

Iezzoni LI, Daley J, Heeren T, et al. Identifying complications of care using administrative data. Med Care. 1994;32(7):700–15.

Arcaya MC, Tucker-Seeley RD, Kim R, et al. Research on neighborhood effects on health in the United States: a systematic review of study characteristics. Soc Sci Med. 2016;168:16–29.

Oakes JM, Andrade KE, Biyoow IM, et al. Twenty years of neighborhood effect research: an assessment. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2015;2(1):80–7.

Oakes JM. Commentary: advancing neighbourhood-effects research–selection, inferential support, and structural confounding. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(3):643–7.

Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(11):1783–9.

Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:125–45.

Schwarz D. What’s the Connection Between Residential Segregation and Health? 2018. Available at: https://www.rwjf.org/en/blog/2016/03/what_s_the_connectio.html. Accessed 27 Nov 2020.

Woo B, Kravitz-Wirtz N, Sass V, et al. Residential segregation and racial/ethnic disparities in ambient air pollution. Race Soc Probl. 2019;11(1):60–7.

Mayne SL, Hicken MT, Merkin SS, et al. Neighbourhood racial/ethnic residential segregation and cardiometabolic risk: the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2019;73(1):26–33.

Yu CY, Woo A, Hawkins C, et al. The Impacts of residential segregation on obesity. J Phys Act Health. 2018;15(11):834–9.

Mayne SL, Yellayi D, Pool LR, et al. Racial residential segregation and hypertensive disorder of pregnancy among women in Chicago: analysis of electronic health record data. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31(11):1221–7.

Williams AD, Wallace M, Nobles C, et al. Racial residential segregation and racial disparities in stillbirth in the United States. Health Place. 2018;51:208–16.

Mehtsun WT, Figueroa JF, Zheng J, et al. Racial disparities in surgical mortality: the gap appears to have narrowed. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(6):1057–64.

Health in all policies: Helsinki statement. Framework for country action 2013. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506908. Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

Hayanga AJ, Zeliadt SB, Backhus LM. Residential segregation and lung cancer mortality in the United States. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(1):37–42.

Haas JS, Earle CC, Orav JE, et al. Racial segregation and disparities in cancer stage for seniors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):699–705.

Sarrazin MV, Campbell M, Rosenthal GE. Racial differences in hospital use after acute myocardial infarction: Does residential segregation play a role? Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(2):w368–78.

Dimick J, Ruhter J, Sarrazin MV, et al. Black patients more likely than whites to undergo surgery at low-quality hospitals in segregated regions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6):1046–53.

Higgins RS. Truth and consequences: it’s not a game anymore. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(3):228.

Azap RA, Paredes AZ, Diaz A, et al. The association of neighborhood social vulnerability with surgical textbook outcomes among patients undergoing hepatopancreatic surgery. Surgery. 2020;168(5):868–75.

Timberlake JM, Ignatov MD. Residential Segregation May 10, 2017, 2014. Available at: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199756384/obo-9780199756384-0116.xml. Accessed 27 Nov 2020.

Thornton RL, Glover CM, Cene CW, et al. Evaluating strategies for reducing health disparities by addressing the social determinants of health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(8):1416–23.

Morrill R. On the measure of spatial segregation. Geogr Res Forum. 1991;11:25–36.

Wong D. Spatial dependency of segregation indices. Can Geogr. 1997;41(2):128–36.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Alessandro Paro, Djhenne Dalmacy, J. Madison Hyer, Diamantis I. Tsilimigras, Adrian Diaz, and Timothy M. Pawlik have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paro, A., Dalmacy, D., Madison Hyer, J. et al. Impact of Residential Racial Integration on Postoperative Outcomes Among Medicare Beneficiaries Undergoing Resection for Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 28, 7566–7574 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-10034-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-021-10034-w