Abstract

To improve the poor water solubility and dissolution rate of the oral hypoglycemic drug glibenclamide, it was molecularly dispersed in Neusilin® UFL2, an amorphous synthetic form of magnesium aluminometasilicate, at different proportions; the physicochemical and biopharmaceutical properties, as well as the stability of the four different batches recovered were characterised, and it was determined that complete dispersion of glibenclamide in the amorphous polymer was obtained at the drug to Neusilin ratio of 1 to 2.5. Completely amorphous dispersion was proven by Thermal Analysis and X-Ray Powder Diffractometry. Very small particles were obtained, ranging from approximately 200 to 400 nm. The amorphous batches were physically and chemically stable for the entire duration of experiments. The physicochemical properties of the four batches were compared to those of the starting materials and physical mixtures of Neusilin® UFL2 and glibenclamide, the latter showing the typical behaviour of simple mixes, i.e., the additivity of properties of single components. The dissolution studies of the four solid dispersions revealed a very high dissolution rate of the completely amorphous batches (Batches 3 and 4), behaviour that was ascribed to their high Intrinsic dissolution rate due to the amorphous characteristics of the solid dispersions, to their very small particle size, and to the presence of polysorbate 80 that improved solid wettability. The technique under investigation thus proved effective for recovering stable amorphous dispersions of very small particle sizes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Glibenclamide (GLB), an oral hypoglycemic drug in the sulfonylureas class, is widely used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (1). It is a poorly water soluble active pharmaceutical ingredient (∼38 μmol/L at 37°C) (2). with poor bioavailability after oral administration (3–5). Several attempts were made to improve GLB particle dissolution and bioavailability, by modifying the crystalline form (6). through controlled crystallization (7). by complexation with cyclodextrines (8) or by solid dispersions (9). and by producing nanocrystals (10,11).

Solid dispersion, the dispersion of drugs in an amorphous matrix, has been considered by many as an efficient method for improving drug solubility and/or dissolution rate (12–15), according to the Noyes-Whitney law (16).

However, even though the drug is molecularly dispersed in the polymeric matrix in amorphous solid dispersions, a fact that strongly contributes to particle dissolution, the size of the solid particles generally ranges between approximately 3 and 10 μm (17,18). More recently and rarely, in three studies, particles of solid dispersions have been obtained in the nanometric size: amorphous particles in the nano-range of sizes of felodipine and PVP were obtained because of the strong interaction between the drug and the polymer (19). the bioavailability of sirolimus was improved by producing nanoparticles of drug dispersed in PVP K30 by using a supercritical antisolvent process (20). and nanoparticle solid dispersions of raloxifene in PVP were prepared by using a common spray drying technique (21).

With these factors in mind, the objective of this study was to select an excipient and a preparation method able to yield amorphous solid dispersions in the nanometric range.

To this end, glibenclamide was dispersed in a relatively new amorphous material, Neusilin® UFL2, an amorphous, synthetic form of magnesium aluminometasilicate, that is widely used for pharmaceutical applications as a carrier and filler for improving the quality of tablets, powders, granules and capsules.

More recently, its use has been proposed in solid dispersions because of its ability to favor the amorphisation of drugs under co-grinding (22–25) and hot-melt granulation (26–28).

Thus the objective of this study was to obtain amorphous solid dispersion of glibenclimide in Neusilin® UFL2 with particle sizes in the nanometric range.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Glibenclamide (GLB) was kindly supplied by Menarini Manufacturing Logistics and Service (Florence, Italy) as white crystalline powder. Native crystals are indicated as NCs in the text and were stored in a desiccator in presence of P2O5 as desiccant during the experiment time interval. Neusilin® UFL2 (NEU) was kindly supplied by Seppic (Paris, France). Ultrapure water was produced by the Gradient Milli-Q® (Millipore, Molsheim, France). Chemicals, supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany), were all of analytical grade. Completely amorphous glibenclamide was prepared by quench-cooling of the melt according to Wojnarowska (29) and stored in a desiccator in presence of P2O5 as desiccant during the experiment time interval.

Preparation of Glibenclamide-Neusilin® UFL2 Samples

As a consequence of preliminary tests, several mixtures of GLB and NEU were prepared at different NEU amounts to find the ratio best able to promote the complete amorphisation of the mixture under treatment:

-

Batch 1: GLB 100 mg + NEU 125 mg (1:1.25) (theoretical GLB content 44.4% by weight);

-

Batch 2: GLB 100 mg + NEU 200 mg (1:2) (theoretical GLB content 33.3% by weight);

-

Batch 3: GLB 100 mg + NEU 250 mg (1:2.5) (theoretical GLB content 28.6% by weight);

-

Batch 4: GLB 100 mg + NEU 500 mg (1:5) (theoretical GLB content 16.7% by weight).

All mixtures were dissolved under stirring in 20 g of dichloromethane, and then 25 mg of polysorbate 80 were added to the mixture to prevent particle agglomeration. The solvent was then evaporated under reduced pressure at 35°C (Rotavapor® R-210, Buchi, Flawil, Switzerland; vacuum pump, V-710, Buchi, vacuum level 680 mmHg). Batches were stored in a desiccator in presence of P2O5 as desiccant during the experiment time interval. In addition to Batches 1–4, four physical mixes were prepared of the same composition of Batches 1–4. To distinguish these last products to the previously described batches, they are identified as physical mixtures (PMs):

-

PM 1: GLB 100 mg + NEU 125 mg (1:1.25);

-

PM 2: GLB 100 mg + NEU 200 mg (1:2);

-

PM 3: GLB 100 mg + NEU 250 mg (1:2.5);

-

PM 4: GLB 100 mg + NEU 500 mg (1:5).

They were prepared by simply mixing GLB and NEU in a mortar and storing them in a desiccator in presence of P2O5 as desiccant during the experiment time interval.

The physicochemical properties of all the sampleswere evaluated using different analytical methods.

HPLC Method

The chemical stability of GLB during processing and the GLB content in solid dispersions were evaluated through HPLC analysis, performed using an HPLC 1090 Hewlett Packard Series I (Ramsey, MN, USA) equipped with a Hewlett Packard HP1100 MSD Chemstation Rev. A.08.03. A reverse phase column was used at 25°C (C18, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm in particle size) (GL Science, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). Isocratic elution with 0.1% orthophosphoric acid: acetonitrile: methanol 20:50:30 (V/V) was used at a flow rate of 1.0 ml min−1. The experimental pH of the mobile phase 5.4 was measured by a pHmeter (Jenway 3510, Essex, England) equipped with a pH electrode (Jenway, Essex, England) calibrated with appropriate standard solutions. The mobile phase was prepared freshly and degassed by sonicating for 5 min before use. 1.0 mg of GLB were dissolved in 10.0 ml of mobile phase and passed through 0.45-μm filters (Millipore, Molsheim, France). The volume of injection was 20 μL, and the flow rate was 1 ml min−1. Detection was done at 210 nm. Evaluations were assessed by considering the retention time of chromatogram peaks and peak area. Under the conditions used, a typical GLB peak had a retention time of 2.97 min.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Particle morphology was determined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Stereoscan 360, Cambridge Instruments, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Samples were mounted on a metal stub with double-sided adhesive tape and then sputtered under vacuum with a gold layer of about 200-Å thickness using a metallizator (Balzer MED 010, Linchestein). The particle size of coarse GLB native crystals (size >3.0 μm) was determined by measuring the Ferret’s diameter of 500 particles.

Dynamic Light Scattering Analysis

Particle size in the nanometric range was determined by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) (Zetasizer Nano S90, Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK), by dispersing particles in water by vortexing or sonication. During the analyses, the attenuation and the polydispersity index were checked to verify the appropriateness of the measurements.

Thermogravimetric Analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis was used to determine the sample water content and was carried out by Simultaneous Thermal Analysis (Simultaneous Thermal Analyser, STA 6000, Perkin Elmer, Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), under nitrogen atmosphere (20 ml min−1) in 0.07 ml open aluminium oxide pans. STA was calibrated for temperature and heat flow with three standard metals (tin, indium and zinc), taking into account their expected melting temperatures (231.93, 156.60, 419.53°C, respectively), and for weight with an external Perkin Elmer standard (Calibration Reference Weight P/N N520-0042, Material lot 91101 GB, Weight 55.98 mg, 01/23/08 VT). Calibration was repeatedly checked to assure deviation ≤± 0.3°C. Samples were heated from room temperature to 190°C at a heating rate of 10°C min−1.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry Analysis

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) analysis was performed on a Pyris 1 calorimeter (Perkin Elmer, Co. Norwalk, USA) equipped with a cooling device (Intracooler 2P, Cooling Accessory, Perkin Elmer, Co. Norwalk, USA). A dry purge of nitrogen gas (20 ml min−1) was used for all runs. DSC was calibrated for temperature and heat flow using a pure sample of indium and zinc standards. Sample mass was about 4–5 mg, and aluminium perforated pans of 50 μl were used. Samples were heated from room temperature to 190°C at a heating rate of 10°C min−1.

The DSC was carried out to characterise the sample solid state and the degree of crystallinity; the latter was calculated by taking into account the melting enthalpy value of the pure 100% crystalline form (GLB native crystals) and the relative enthalpy value of samples under investigation.

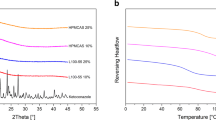

X-Ray Powder Diffractometry

To assess the solid state of the studied samples and to follow their physical stability, X-ray powder diffractometry (XRPD) was used. A Philips PW 1730 (Philips Electronic Instruments Corp., Mahwah, NJ, USA) model was used as X-ray generator for Cu Kα radiation (λ α1 = 1.54056 Å, λ α2 = 1.54430 Å), and the experimental X-ray powder patterns were recorded on a Philips PH 8203 recorder. The goniometer supply was a Philips PW 1373, and the channel control was a Philips PW 1390. Data were collected in the discontinuous scan mode using a step size of 0.01° 2α. The scanned range was 2 θ to 40° (2 θ).

The crystallinity degree of powders was evaluated by XRPD and calculated according to a previously described method (30). Briefly, a calibration curve was determined from physical mixtures of pure GBC considered completely crystalline (100% crystalline), and GBC obtained from quench-cooling procedure considered completely amorphous (100% amorphous). The calibration curve was determined, in presence of an internal standard, by calculating the total area (A tot ) of the diffraction patterns (crystalline + amorphous) and the area (A Cr ) of the crystalline part (the area over the peak baseline). The powder crystallinity degree was expressed according to the following Eq. (1):

The crystallinity degree was the average value of three different measurements. The statistical significance was evaluated by a One-Way ANOVA test for α = 0.05.

Intrinsic Dissolution Rate Study

The intrinsic dissolution study was carried out by the rotating disk method (31) on native GLB and the four Batches 1–4. Thirteen-mm diameter tablets were obtained by compressing 300 mg of powder in a Perkin-Elmer hydraulic press for IR spectroscopy KBr disks, at a force of 15 kN for 10 min. This process yielded tablets with a surface area of 132.73 mm2 that would not disintegrate during the test. Tablets were inserted into a stainless steel holder, so that only one face was exposed to the dissolution medium. The holder was then connected to the stirring motor of a dissolution apparatus (Erweka DT6, Gloucestershire, England), centrally immersed in a 1000-ml beaker containing 900 ml of phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) (buffer solution, USP Pharmacopoeia) at 37°C and rotated at 100 rpm. Suitable aliquots were withdrawn with a regenerated cellulose filter syringe (0.45 μm; Filalbet, Rosello, Spain) at specified times and assayed for drug content spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 457 nm. A correction was calculated for cumulative dilution caused by replacement of the sample with an equal volume of original medium. Each test was repeated six times. Low standard deviations were obtained, indicating the good reproducibility of this technique. The intrinsic dissolution rates (IDR) were calculated from the slope of the straight line of cumulative drug release.

Dissolution from the Particle Samples

Particle dissolution of native GLB and Batches 1–4 was carried out in a 1000-ml beaker containing 900 ml of phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at 37°C and rotated at 50 rpm (Erweka DT6, Gloucestershire, England); sink conditions were assured during the experiments. Suitable aliquots were withdrawn with a regenerated cellulose filter syringe (cellulose acetate of 0.45 μm, Filalbet, Barcelona, Spain) at specified times and assayed for drug content spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 457 nm. A correction was calculated for cumulative dilution caused by replacement of the sample with an equal volume of original medium. Each test was repeated six times. Low standard deviations were obtained, indicating the good reproducibility of this technique. Results were expressed as percentage of total drug release.

Long-Term Stability Study

The long term stability study (12 months) was carried out according to the ICH (stability testing of new drug substances and products, Q1A(R2)) (32) by storing samples in tightly closed glass containers at 25°C ± 2°C/60% RH ± 5% RH. The stability was evaluated by measuring the particle size and by assessing changes in the physical solid form of the GBC samples. In addition, changes in dissolution behaviour were measured by IDR and dissolution test.

Statistical Analysis

The crystallinity degree, dissolution data, and particle size were analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), using a Bonferroni test. The statistical analysis was conducted using an Origin® software (version 8.5) (Northampton, Massachusetts, USA). Results are shown as mean ± SD (standard deviation) and considered significantly different when P < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Physicochemical Characterisation of Glibenclimide Samples

Native GLB crystals appeared as irregular parallelepipeds (Fig. 1a). Coarse particles coexisted with smaller irregular particles. The mean geometric particle diameter was approximately 32.23 ± 2.91 μm (Table I).

SEM microphotographs of glibenclamide samples. a Native crystals (1000x); b Amorphous glibenclamide (3500x); c Pure Neusilin® UFL2 (2500x); d Physical Mixture PM 1 (2500x); e Physical Mixture PM 2 (2500x); f Physical mixture PM 3 (2500x); g Physical mixture PM 4 (2500x); h Batch 1 (8000x); i Batch 2 (8000x); l Batch 3 (8000x); m Batch 4 (8000x)

Amorphous GLB appeared as irregular particles characterised by smoothed edges (Fig. 1b). The mean geometric particle diameter was approximately 2.80 ± 0.34 μm (Table I).

In Neusilin® UFL2, large spherical agglomerates coexisted with small irregular ones, probably formed from the breakage of the spherical agglomerates (Fig. 1c). The mean geometric particle diameter was 7.78 ± 4.25 μm (Table I).

Four physical mixtures of GLB-NEU were prepared (PMs 1, 2, 3 and 4) and analysed under scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 1d–g). In the photomicrographs, large particles of GLB or agglomerated of Neusilin are dispersed in smaller particles. Four batches of solid dispersions of different ratios of glibenclamide and Neusilin® UFL2 were prepared. Particles of Batch 1 (GLB-NEU 1:1.25 ratio) (Fig. 1h) appeared irregular and isodimensional and were characterised by quite smooth, round edges. Some coarse particles existed and were grouped with smaller particles. The crystallization procedure strongly reduced the particle size (0.52 ± 0.41 μm) compared to the original particles. Batch 2 (GLB-NEU 1:2) (Fig. 1i) had irregular and round small particles. Coarser ones disappeared and a more homogeneous particle distribution could be observed. The mean geometric particle size was reduced to 0.39 ± 0.10 μm. Far smaller particle size (0.29 ± 0.22 μm) and narrow particle distribution was highlighted for Batch 3 (GLB-NEU 1:2.5) (Fig. 1l), which had isodimensional, round and smooth particles. The particle shape and distribution of Batch 4 (GLB-NEU 1:5) (Fig. 1m) were similar to those of Batch 1; the particles in this last batch were still round and irregular, and had coarse particles in presence of small ones (0.47 ± 0.42 μm). DSC analysis (Fig. 2) of pure GLB made it possible to evaluate its thermal behaviour by calculating the extrapolated onset temperature (175.89 ± 0.63°C) and the enthalpy content (95.34 ± 4.29 J g−1) of the melting peak (Table II). The water content (0.77 ± 1.22%) was consistent with an anhydrous solid (Table II). The 100% crystallinity degree was assigned to this sample.

In the DSC thermogram (Fig. 2) of amorphous GLB, the only glass transition temperature at nearly 62.20 ± 1.30°C in accordance to Wojnarowska (29) was observed. The water content (7.24 ± 1.13%) was consistent with an amorphous material characterised by a certain tendency to retain water (Table II).

The thermogram of pure Neusilin (Fig. 2) was characterised by a broad endotherm between 40 and 130°C due to the loss of hydration water from the amorphous material. The loss of water from NEU was 4.47 ± 0.75%, a value that is in agreement with the NEU technical document (Table II).

DSC thermograms of all the four batches of GLB-NEU did not exhibit melting peaks. In Fig. 2, the thermogram for the Batch 3 is given as an example, the thermograms of the other batches being similar. The absence of the GLB melting peak might indicate that amorphous mixtures were formed at any ratio, but this preliminary conclusion will be contradicted by XRPD analysis. The water content of Batches 1 to 4 could account for the hydration into amorphous solids (Table II). The water content of solid dispersions, ranging approximately between 5 and 9%, may depend on the amorphous state and very low mean geometric particle size (high particle surface) of the samples that may explain the capacity of amorphous forms to absorb water.

The physical mixes showed a thermal behaviour compatible with a physical mix. The thermogram of the PM 3 (Fig. 2e) showed the GLB melting endotherm at 171.00 ± 0.55°C. The variation in enthalpy content associated to the GLB melting is lower than the melting of the pure compound (ΔH 37.28 ± 2.51 J/g), as expected for a mixture.

In Fig. 3, the typical X-ray powder diffractogram of the crystalline GLB is showed. The absence of typical patterns of the GLB obtained by quench-cooling confirmed the completely amorphous character of this sample. NEU also appeared completely amorphous. XRPD of Batches 1–4 contradicted the preliminary results provided by the DSC results. In fact, the existence of GLB peaks in the Batch 1 diffractogram indicated that the mixture was not completely amorphous. By calculating the crystallinity degree from XRP diffractometry, it was possible to conclude that the degree of crystallinity was 10.4%. A slightly lower crystallinity degree (4.7%) was observed for Batch 2. Thus, the absence of the GLB melting peak in the DSC thermograms of Batches 1 and 2 was not due to the completely amorphous state of the solid, but rather to the fact that the almost amorphous mixture favoured the complete interaction of the two compounds during heating and led to a completely amorphous mix and the disappearance of the melting peak. This behaviour is typical of strongly interacting compounds (30).

Batches 3 and 4, on the contrary, appeared completely amorphous also under the XRPD analysis; this evidence made it possible to conclude that Batches 3 and 4 were completely amorphous.

In the diffractograms of physical mixtures PM 1–4, it was possible to identify the presence of typical diffraction peaks of GLB, the intensity of which are proportional to the amount of the drug into the mix.

The GLB chemical stability was evaluated by HPLC. The integration of the GLB peak area for the native crystals and the amorphous form ranged from 99.50 to 99.98%, indicating the sample purity (Table II) and in particular that no degradation occurred during the preparation of the GLB amorphous form.

The four solid dispersions (Batches 1–4) showed a GLB content very close to the theoretical content, as reported in Table II.

Intrinsic Dissolution Rate and Dissolution from the Particle Samples

Intrinsic Dissolution Profiles are shown in Fig. 4. The Intrinsic Dissolution Rates (IDRs) (Table III) were calculated from the slope of the strength lines of cumulative drug release. The IDR of native crystals of GLB was rather low, as expected for a poorly soluble drug and as also previously reported (11). The IDR strongly increased for Batches 1–4. Since as already reported, IDR was not influenced by the particle size (33) because differences in particle size are diminished by the high compression pressure used to prepare sample compacts; most likely it was influenced by the amorphous character of the solid dispersions. In addition, it is possible to observe that the IDRs increased in the order Batch 1 < Batch 2 < Batches 3 and 4, and thus proportionally to the crystallinity degree, which was respectively 10.4, 4.7 and 0.0% (the last value for both Batches 3 and 4). The very low differences in IDR between Batches 3 and 4 are not statistically significant (significance level P < 0.05) (Fig. 5).

The polysorbate 80 undoubtedly favours the surface wettability (33,34). and thus it concurs to improve the IDR of Batches 1–4 with the respect to that of native crystals.

The results of particle dissolution are shown in Fig. 3. The dissolution curves were quite similar for GLB native crystals and Batch 1, while they increased from Batch 2 to Batch 4, and were the best for Batch 3. These results are firstly clearly correlated to the IDRs and thus to the crystallinity degree %, but these parameters are not the ones that affected particle dissolution. Actually, the fact that Batch 3 had the lowest geometric mean particle diameter may be a significant factor in explaining why it exhibited the best dissolution behaviour. In addition, the contribution of polysorbate to the improved wettability explains the better dissolution rate of solid dispersions that native crystals. It is also necessary to consider that in spite of NEU being an insoluble carrier, solid dispersions, in particular Batches 3 and 4 where the GLB is completely amorphous, showed excellent dissolution behaviour. The improvement in dissolution behaviour of solid dispersions has been more frequently achieved by using soluble carriers (12). However, it is not infrequent that also insoluble carriers may favour the dissolution rate of poorly water-soluble drugs from solid dispersions (35,36).

When the carrier is insoluble and not swellable and up to an appropriate drug-carrier proportion, one can suppose that drug controls the diffusion through the carrier, particularly when the drug exceeds the solubility of the carrier (37). In our case, the amorphization of the drug improved the drug solubility with the consequence that diffusion is controlled by the drug. At higher carrier weight fractions, the drug release becomes controlled by dissolution of the carrier (37) that in our case decreased the dissolution rate. This may explain why Batch 4, that is characterised by a higher percentage of NEU, exhibited a slightly lower dissolution rate than Batch 3.

Long-Term Stability of the Samples

The long-term stability of the GLB solid dispersions was evaluated by assessing the solid state stability and dissolution rates. The mean geometric particle size of the samples under evaluation remains unchanged during the time interval of stability studies. In particular, the mean geometric particle size of Batches 1–4, in spite of the particles being in the nanometric range, did not significantly change (significance level P < 0.05), probably because of the presence of the polysorbate that prevents the particle agglomeration. The DSC thermograms did not show differences compared to the same sample at time 0 (Table II), while XRP diffraction analysis showed a slight increase in the crystallinity degree for Batches 1 and 2, which were not completely amorphous at time 0 (Table II). Thus, when some crystalline nuclei were present in the mixture, it was possible to observe a tendency to crystallization that on the contrary was not observed when the mixture was completely amorphous. The completely amorphous samples proved to be highly stable after 1 year, and no crystallization was observed with time. IDR analysis was repeated again, and no significant changes in IDRs were observed with the exception of Batches 1 and 2, which showed slightly decreased IDRs, certainly as a consequence of the crystallization (Table III).

CONCLUSIONS

A new and very interesting approach for improving glibenclamide particle dissolution was achieved by dispersing glibenclamide in Neusilin® UFL2, an amorphous synthetic form of magnesium aluminometasilicate, in presence of polysorbate 80. The drug dispersion into the amorphous material favored the formation of stable amorphous solid dispersions (Batches 3 and 4) and also the formation of very small particles of nearly 200–400 nm. The small particle size as well as the dispersion in an insoluble amorphous matrix improved the drug dissolution from particles. The best particle dissolution of Batch 3 makes it possible to select it as the best sample. Its excellent dissolution profile, together with its good physical stability holds promise for interesting applications in the development of solid dosage forms of glibenclamide with increased bioavailability.

REFERENCES

Inzucchi GL. Oral antihyperglycemic therapy for type 2 diabetes: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;287:360–72.

Hartke K. Comments to the European Pharmacopoeia. 14th ed. Stuttgart: WVG mbH; 2001.

Borchert H, Müller H, Pfeifer S. Zur biologischen verfugbarkeit von glibenclamide in abhangigkeit von der teilchengrosse. Pharmazie. 1976;31:307–9.

Arnquist HJ, Karlberg BE, Melander A. Pharmacokinetics and effects of glibenclimide in two formulations, HB 419 and HB 420, in type 2 diabetes. Ann Clin Res. 1983;37:21–5.

Chalk JB, Patterson M, Smith MT, Eadie MJ. Correlation between in vitro dissolution, in vivo bioavailability and hypoglycaemic effect of oral glibenclamide. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1986;31:177–82.

Suleiman MS, Najib NM. Isolation and physicochemical characterization of solid forms of glibenclamide. Int J Pharm. 1989;50:103–9.

Elkordy AA, Jatto A, Essa E. In situ controller crystallization as a tool to improve the dissolution of glibenclamide. Int J Pharm. 2012;428:118–20.

Esclusa-Díaz MT, Torres-Labandeira JJ, Kata M, Vila-Jato JL. Inclusion complexation of glibenclamide with 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin in solution and in solid state. Eur J Pharm Sci. 1994;1:291–6.

Chauhan B, Shimpi S, Paradkar A. Preparation and evaluation of glibenlcamide-polyglycolized glycerides solid dispersions with silicon dioxide by spray drying technique. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2005;26:219–30.

Shah SR, Parikh RH, Chavda JR, Sheth NR. Glibenclamide nanocrystals for bioavailability enhancement: formulation design, process optimization, and pharmacodynamic evaluation. J Pharm Innov. 2014;9:227–37.

Martena V, Censi R, Hoti E, Malaj L, Di Martino P. Preparation of glibenclamide nanocrystals by a simple laboratory scale ultra cryo-milling. J Nanoparticle Res. 2013;15:1712–22.

Leuner C, Dressman J. Improving drug solubility for oral delivery using solid dispersions. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50:47–60.

Vasconcelos T, Sarmento B, Costa P. Solid dispersions as strategy to improve oral bioavalability of poor water soluble drugs. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:1068–75.

Malaj L, Censi R, Mozzicafreddo M, Pellegrino L, Angeletti M, Gobetto R, et al. Influence of relative humidity on the interaction between different aryl proprionic acid derivatives and poly(vinylpyrrolidone) K30. Evaluation of the effect on drug bioavailavbility. Int J Pharm. 2010;398:61–72.

Censi R, Martena V, Hoti E, Malaj L, Di Martino P. Preformulation study of nicergoline solid dispersions. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2014;115:2439–46.

Noyes A, Whitney WR. The rate of solution of solid substances in their own solutions. J Am Chem Soc. 1897;19:930–4.

Papageorgiou GZ, Bikiaris D, Karavas E, Politis S, Docoslis A, Park Y, et al. Effect of Physical state and particle size distribution on dissolution enhancement of Nimodipine/PEG solid dispersions prepared by melt mixing and solvent evaporation. AAPS. 2006;J8:E623–31.

Pouton CW. Formulation of poorly water-soluble drugs for oral administration: physicochemical and physiological issues and the lipid formulation classification system. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2006;29:278–87.

Karavas E, Georgarakis E, Sigalas MP, Avgoustakis K, Bikiaris D. Investigation of the release mechanism of a sparingly water-soluble drug from solid dispersions in hydrophilic carriers based on physical state of drug, particle size distribution and drug-polymer interactions. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2007;66:334–47.

Kim MS, Kim JS, Park HJ, Cho WK, Cha KH, Hwang SJ. Enhanced bioavailability of sirolimus via preparation of solid dispersion nanoparticles using a supercritical antisolvent process. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:2997–3009.

Tran TH, Poudel BK, Marasini N, Chi SC, Choi HG, Yong CS, et al. Preparation and evaluation of raloxifene-loaded solid dispersion nanoparticle by spray-drying technique without an organic solvent. Int J Pharm. 2013;25:50–7.

Gupta MK, Vanwert A, Bogner RH. Formation of physically stable amorphous drugs by milling with Neusilin. J Pharm Sci. 2003;92:536–51.

Bahl D, Bogner RH. Amorphization of indomethacin by co-grinding with Neusilin US2: amorphization kinetics, physical stability and mechanism. Pharm Res. 2006;23:2317–25.

Vadher AH, Parikh JR, Parikh RH, Solanki AB. Preparation and characterization of co-grinded mixtures of aceclofenac and Neusilin US2 for dissolution enhancement of aceclofenac. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2009;10:606–14.

Lou H, Liu M, Wang L, Mishra SR, Qu W, Johnson J, et al. Development of a mini-tablet of co-grinded prednisone–neusilin complex for pediatric use. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2013;14:950–8.

Gupta MK, Goldman D, Bogner RH, Tseng YC. Enhanced drug dissolution and bulk properties of solid dispersions granulated with a surface adsorbent. Pharm Dev Technol. 2001;6:563–72.

Gupta MK, Bogner RH, Goldman D, Tsend YC. Mechanism for further enhancement in drug dissolution from solid-dispersion granules upon storage. Pharm Dev Technol. 2002;7:103–12.

Gupta MK, Tseng YC, Goldman D, Bogner RH. Hydrogen bonding with adsorbent during storage governs drug dissolution from solid-dispersion granules. Pharm Res. 2002;11:1663–72.

Wojnarowska Z, Grzybowska K, Adrjanowicz K, Kaminski K, Paluch M, Hawelek L, et al. Study of the amorphous glibenclamide drug: analysis of the molecular dynamics of quenched and cryomilled material. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:1692–707.

Gashi Z, Censi R, Malaj L, Gobetto R, Mozzicafreddo M, Angeletti M, et al. Differences in the interaction between aryl propionic acid derivatives and poly(vinylpyrrolidone) K30: a multi-methodological approach. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:4216–28.

Banakar UV. In: Swarbrick J, editor. Pharmaceutical dissolution testing. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1992. p. 55–105.

ICH Q1A(R2) International Conference on Harmonization, Stability testing of new drug substances and products. 2003.

Martena V, Censi R, Hoti E, Malaj L, Di Martino P. Indomethacin nanocrystals prepared by different laboratory scale methods: effect on crystalline form and dissolution behavior. J Nanoparticle Res. 2012;14:1275–89.

Okonogi S, Puttipipatkhachorn S. Dissolution improvement of high drug-loaded solid dispersion. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2006;7:E148–53.

Hirasawa N, Ishise S, Miyata H, Danjo K. Physicochemical characterization and drug release studies of nilvadipine solid dispersions using water-insoluble polymers as carriers. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2003;29:339–44.

Najib N, Suleiman MS. The kinetics of drug release from ethylcellulose solid dispersions. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 1985;11:2169–81.

Corrigan OI. Mechanisms of dissolution of fast release solid dispersions. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 1985;11:697–724.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Mr. Luca Parente for his kind contribution to the experimental work and Alessandro Di Michele for his kind contribution with the scanning electron microscopy. They would also like to thank Sheila Beatty for editing the English usage of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Censi, R., Gigliobianco, M.R., Dubbini, A. et al. New Nanometric Solid Dispersions of Glibenclamide in Neusilin® UFL2. AAPS PharmSciTech 17, 1204–1212 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-015-0457-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-015-0457-z