Abstract

This paper presents an analysis of the non-linear vibrations of beams, which play a crucial role in various industrial and construction structures. Understanding the transverse vibrations of beams and accurately determining their frequency response is essential for achieving optimal design and structural performance. The novelty of this study lies in conducting a transverse non-linear vibration analysis of a three-dimensional beam while considering the effect of mid-plane elongation. By incorporating this aspect into the analysis, the study aims to provide deeper insights into the dynamic behavior of beams subjected to non-linear effects. A multiple-time scale approach has been adopted to conduct this research. To verify the accuracy of the method as well as the accuracy of the outcomes gained from this method, a contrast has been made with the 4th-order Runge-Kutta technique, which indicates that the results obtained are acceptable. The frequency response of the beam indicates the presence of a phenomenon of splitting into two non-linear branches during the three-dimensional vibrations of the beam, as well as a hardening state in the frequency response as a result of stretching the middle plane of the beam. Furthermore, a parametric study was conducted in which different parameters were examined to determine the starting point of non-linear bifurcation. As a result, the damping coefficient and resonance deviation parameter are two factors that affect the preference for critical bifurcation over safe bifurcation. Furthermore, the stretching of the middle plane results in a higher non-linear term coefficient in the vibration equations of the beam, which increases the oscillation frequency of the beam.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-linear beam vibration modeling helps in the design and analysis of mechanical structures subjected to dynamic loads. This includes applications in aerospace, automotive, and civil engineering, where accurate prediction of structural responses under varying conditions is crucial for ensuring safety and performance [1, 2]. In both industry and construction, beams are one of the most important structural elements. In addition to applications in micro- and nano-scale structures, this structural member can also be used in macro-scale structures, such as airplane wings, flexible satellites, and bridge spans [3,4,5]. It is, therefore, possible to model and analyze many members of the structure as beams. To achieve a suitable design in beam-shaped members, it is particularly important to understand how the beam vibrates in transverse modes and to determine its natural frequencies. It is more evident that fatigue of the beam's constituent materials and its overall structural failure occurs in large-range vibrations, where effects raised around the natural frequency play an even greater role [6,7,8,9,10]. As a result, the non-linear effects in the equations governing beam vibrations are of greater importance [11].

Non-linear terms in vibration equations can be derived from geometrical, inertial, or material sources [12]. The stretching of the middle plane and the presence of large curvatures can result in geometric non-linearity. Material non-linearity is a result of a non-linear relationship between stress and strain in the beam material. Additionally, asymmetrically distributed and concentrated masses contribute to the non-linearity of inertia. In some studies, the vibration behavior of mechanical systems has been modeled using multi-degree-of-freedom models [13,14,15,16,17] or continuous media theory [18, 19]. Based on Euler-Bernoulli's theory, it is assumed that beam cross-sections remain perpendicular to the main axis during deformation [20]. According to this theory, transverse vertical strains and shear deformations are not taken into account. A study conducted by Abohamer et al. [21] delves into the dynamic analysis of a novel three-degree-of-freedom mechanism comprising two interconnected segments. The system is subject to external harmonic forces to induce motion. The dynamical system’s stability and vibration, as explored by Abohamer et al. [22], have been rigorously modeled. The homotopy analysis method was used by Javidi et al. [23] to investigate the non-linear behavior of a beam under axial load and to obtain a suitable expression to express the frequency of such non-linear behavior. This method was applied by Sediqi et al. [24] to analyze beam vibrations with non-linear damping, and acceptable results were obtained. Liu et al. have investigated the non-linear forced vibrations of functionally graded three-phase composite cylindrical shells [25]. Zheng et al. [26] studies focus on examining how rotating composite blades chaotically respond to vibrations, specifically looking at resonant responses and the occurrence of double-parameter multi-pulse vibrations. Liu et al. [27] investigated three specific phenomena in the context of a large deployable space antenna experiencing thermal load and internal resonance at a 1:3 ratio. The three phenomena being studied are non-linear vibrations, Andronov-Hopf bifurcations, and Pomeau-Manneville intermittent chaos. This research is the first of its kind to explore these aspects of the LDSA under these specific conditions. Liu et al. [28] studied the non-linear breathing vibrations of an eccentric rotating composite laminated circular cylindrical shell subjected to lateral and temperature excitations. The governing equations of motion are established based on Donnell thin shear deformation theory, von Karman-type non-linear relation, and Hamilton's principle. Mejia-Nava et al. [29] investigated the conditions of creating a non-linear bifurcation in cantilever beams through analytical analysis. Using the multiple time scale method, Ding et al. [30] considered the non-linear vibrations of a supported beam with asymmetric elastic supports, taking into account the effects of shear deformation and rotational inertia. Akkoca et al. [31] modeled the equations for a beam and took into account the effect of elongation in the middle plane. The frequency response of the device was then studied using the multiple time scale method in two modes, primary and secondary resonance. Lewandowski [32] demonstrates a method for analyzing steady-state vibrations of geometrically non-linear systems utilizing a harmonic balance approach with an exponential version. An analysis of the method and the numerical procedure corresponding to it is provided in detail. Geometric non-linearity is described through the von Karman theory. According to the first-order shear deformation theory, Sohani et al. [33] present an analytical procedure for forecasting the non-linear natural frequencies of beams. It is assumed by the non-linear kinematics assumptions that the transverse deflection and mid-plane stretching, which, utilizing von Kármán connections, are defined, will exhibit moderately large deformations. Hooke's law is utilized as the constitutive equation because the strains are small. Hamilton's principle is utilized to derive coupled non-linear longitudinal-transverse motion equations. In the results, the axial and transverse amplitudes of vibrations have a significant effect on the non-linear frequencies. Zamani et al. conducted an examination of large-amplitude free vibrations of simply supported beams [34] utilizing the method of finite elements. According to the Rayleigh-Ritz method, they presented an analytical expression.

Numerous investigations in the realm of beam vibration analysis from a non-linear perspective primarily focus on the inclusion of the third-order non-linear term while disregarding the influence of higher-order terms, subsequently resolving the issue through analytical methods [35,36,37]. A comprehensive review of existing literature underscores a notable gap in the exploration of non-linear beam vibrations under parametric excitation. This article seeks to address this gap by first establishing the governing equations for the non-linear vibrations of a three-dimensional Euler-Bernoulli beam subjected to parametric excitations and midplane elongation. Subsequently, the force response, as well as the beam's frequency response, are ascertained utilizing the multiple time scale method. A detailed examination of the beam’s frequency response is undertaken to elucidate the occurrences of supercritical pitchfork bifurcation and continuous or safe bifurcations. Various design parameters are scrutinized to assess their influence on this significant non-linear phenomenon.

Equations of motion

The geometric model of the clamped-clamped beam and coordinate system are shown in Fig. 1. Partial differential equations controlling the Euler-Bernoulli beam's transverse vibrations, taking into account the variable axial force along the length of the beam, are obtained as follows [38].

In Eq. (1), V(x,t) and W(x,t) are the transverse deformation of the beam in two directions perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the beam. I is the moment of cross-sectional of inertia, m is the mass per unit length, E is the modulus of elasticity, T is the axial force along the length of the beam, t is time, x is displacement, and (px, py, pz) are forces components acting on the beam. In the derivation of these equations, it is assumed that transverse vibrations are carried out slowly; that is, the speed of beam oscillations is low. Also, dynamic stimulation is applied slowly in the upper support. Therefore, the longitudinal inertia term is omitted in these equations.

Galerkin technique is utilized to convert partial differential equations into ordinary differential equations. For this purpose, the hypothesis solution of Eq. (1) is considered as

In line with using the Galerkin technique for the present problem, in Eq. (2), \(\Phi_{1} (x)\) and \(\Phi_{2} (x)\) are assumed as one of the linear modes of beam vibrations in its transverse directions. Therefore, v(t) and w(t) are the time-dependent amplitudes of beam vibrations. The boundary conditions for the beam in Fig. 1 are as follows:

In the above equations, s0 and f(t) are, respectively, the initial static displacement and the dynamic displacement applied to the left support of the beam. According to the defined boundary conditions, at first, the upper support of the beam is under initial static displacement. Then, during vibrations, stimulation is applied to it in the form of dynamic displacement through the upper support. From Eq. (2a), an expression can be obtained to express the axial force. By performing mathematical operations, the axial force is obtained by ignoring its changes along the length of the beam and by ignoring volume forces and other external forces, as follows:

As can be seen in Eq. (3), the obtained axial force is only a function of time. In the continuation of using the Galerkin method, it is assumed that [39, 40]:

By inserting Eq. (3) into Eq. (1), the following equation can be written:

By using Eq. (4), the boundary conditions are defined for the beam, and by applying the Galerkin technique to the latter equations, the following system of equations is achieved. The weight function used in the Galerkin technique is the same as the first linear mode of the clamped-clamped beam.

The Eq. (6) is the characteristic equation of beam vibrations. The coefficients introduced in Eq. (6) are given in the appendix. In the following, the solution of this system of equations will be discussed. The basic conditions for solving this system of equations are considered as zero initial conditions.

Methods

While numerical solution and finite element methods have seen significant development across various engineering disciplines [41,42,43,44,45], the provision of analytical methods remains crucial for addressing non-linear equations and comprehensively understanding system behavior. The multiple time scale method [46,47,48], also known as multiscale analysis or hierarchical modeling, is a technique commonly employed in dynamical systems and mathematical modeling to analyze systems with weakly non-linear behavior. In our study, we utilized the multiple time scale method to address the complex interactions and dynamics observed in the non-linear vibration of the beam. The system of Eq. (6) is solved utilizing the multiple time scale technique. According to this method, these equations are rewritten as follows [49]:

In Eq. (7), ε is a small parameter. According to the multiple time scale method, the answer is considered as Eq. (8):

In this equation, T0=t and T1=εt represent fast and slow time scales. Next, the linear damping term is added to Eq. (7), and then Eq. (8) is inserted into Eq. (7). After that, by adjusting the obtained equations according to the power of the small parameter ε on both sides of the equations, in such a way that equal coefficients ε are placed on both sides of the equation, the collection of linear differential equations that follows is gained:

In Eq. (9), μ is the linear damping coefficient. As can be seen, the solutions of Eq. (9) are interdependent. The solution of the first device is obtained in the form of Eq. (10):

The parametric excitation, which is applied in the form of displacement at the end of the beam in Fig. 1, is expressed by Eq. (11):

In Eq. (10), K is the beam support's dynamic displacement range, as well as Ω is the excitation frequency. By defining the resonance deviation parameter as below, it is possible to check the force response of the system in the sub-harmonic mode [50]. Assuming that the external excitation has primary resonances, the excitation frequency is assumed to be:

in which σ is the detuning parameter. By inserting Eq. (10) into Eq. (9), to prevent the occurrence of secular terms in the solution of the problem, the coefficient \(e^{{i\omega_{0} T_{0} }}\) should be set to zero, as a result:

It is assumed that

where ai and βi, i = 1 and 2 are unknown constants. By incorporating these equations into Eq. (12), there are

By performing a series of mathematical operations on Eq. (14), the following equation is obtained:

The parameters are defined as follows:

According to the examination of vibrations around the stable point of motion, such as the center points in the phase plane diagrams, Eq. (17) is written:

The above equations state that, near the stable points of the vibrating system, the oscillations’ amplitude and phase will not change. According to the mentioned points, the system’s frequency response equations can be gained as follows:

Equation (18) has two obvious and non-obvious solutions. The obvious solution of this equation is a1=a2=0. From solving the system of Eq. (18), it can be concluded that a1=a2. Therefore, according to this result, the frequency response and the amplitude, depending on the time of movement, in the sub-harmonic mode for the non-trivial solution, will be obtained in the following implicit form:

on the other hand

In Eq. (20), β0 is the constant of integration. As a result, according to Eq. (8), the first approximation for the time response is calculated as follows:

For vibrations in the z direction, a similar expression will be obtained according to the result.

Results and discussion

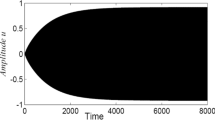

The present problem has been solved numerically to demonstrate the accuracy and correctness of the analytical solution made in this study. Figure 2 illustrates the time-dependent amplitudes of beam vibrations in one of the transverse directions. The analytical results obtained from the method of multiple time scales are in agreement with those obtained from the four-order Runge–Kutta method, as seen in the comparison figure.

Figure 3 compares the time trace of deflection obtained through our present method with the deflection response of the beam's center as determined by Barari et al. [51]. In this case, only transverse vibrations are considered and the other component of out-of-plane vibrations is neglected. A notable observation from these figures is the congruent deflection behavior exhibited by the center of the beam over an extended period, aligning with semi-analytical approaches documented in the literature. Furthermore, a parametric study has been conducted to scrutinize the time-marching response of the central deflection of the beam.

For different values of the resonance deviation parameter, Fig. 4 shows the force response of beam vibrations. According to this figure, the phenomenon of non-linear bifurcation may occur, both safely and catastrophic bifurcations, accompanied by the phenomenon of mutation. In the case of the parameter of deviation from negative resonance, the obvious answer will be transferred to the non-obvious answer without the occurrence of mutation, whereas when the parameter becomes positive, the transition will be accompanied by mutation. It can be seen that the bifurcation starting point for σ = 0, σ = 0.1, and σ = 0.5 occurs in the force range of K = 0.98, K = 1.95, and K = 0.2 respectively. Therefore, with the increase of the detuning parameter and the distance of the frequency of the excitation force from the natural frequency of the structure, the domain of the bifurcation phenomenon increases. Based on the analysis conducted by Nayfeh [52], stable and unstable parts of the answers have been separated. The force response of beam vibrations is illustrated in Fig. 5 as a function of the non-linear term coefficient. Using this figure, it can be seen that the starting point of bifurcation does not change when the coefficient of the non-linear term is changed. The system’s frequency response is shown in Fig. 6, which is obtained by solving Eq. (19). Based on the graph depicted in this figure, it can be seen that the graph is inclined to the right. This indicates that the hardening type has a non-linear effect on the beam equations. Conversely, the phenomenon of consecutive non-linear bifurcations is evident. The starting points of the non-linear bifurcation are specified in this figure.

In particular, when considering structures with doubly-clamped ends, the phenomenon of hardening resonance can be attributed to the tension induced during the oscillatory transverse motion of the beam. This tension, stemming from the dynamic interaction between the beam's motion and its clamped supports, contributes significantly to the observed hardening behavior in the system's resonance response. As displayed in Fig. 7, the force response diagram for several different values of the linear damping coefficient is shown at the point σ = 0.1. As can be displayed in this figure, with the rise of the damping coefficient, the phenomenon of critical bifurcation tends to be a safe bifurcation without mutation phenomenon. Also, by raising the value of the linear damping coefficient, the starting point of bifurcation moves away from the coordinate origin. Figure 8 examines the effect of the parametric excitation coefficient on the frequency response of the system. As it is known, this parameter affects the starting point of non-linear bifurcation.

According to Fig. 9, increasing the non-linear coefficient results in the graph becoming more skewed to the right, which is to say, it becomes more hardening. The results suggest that non-linear effects exhibit a hardening behavior of the system’s equivalent spring. Additionally, as these effects become more pronounced, there is a discernible increase in the degree of amplitude distortion towards the right. Given that the natural frequency is one of the pivotal factors influencing the dynamics of forced vibrations in structures subjected to parametric excitation, its value was thoroughly examined in this study. Figure 10 illustrates the outcomes, indicating a substantial impact of this parameter on the frequency curve of the beam. Specifically, it induces a softening behavior in the stiff spring, as evidenced by the observed trends. Unlike the parametric excitation coefficient, this parameter reduces the hardening effect and also reduces the starting point of the non-linear bifurcation, as opposed to the non-linear stiffness coefficient.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study contributes to the field of structural dynamics by presenting a comprehensive analysis of the non-linear vibrations of beams. By considering the effect of mid-plane elongation in the analysis, the study offers valuable insights into the intricate dynamics of three-dimensional beams. The incorporation of this aspect enhances the accuracy and relevance of the analysis, thereby advancing our understanding of beam vibrations and their implications for structural design. Moving forward, the study’s conclusions can serve as a foundation for further research in this area and inform the development of more robust design methodologies for industrial and construction structures.

Incorporating the elongation of the beam’s middle plane led to the emergence of non-linear terms in the equations, contributing to a hardening state in the frequency response diagram. Notably, an increase in the coefficient of these non-linear terms was observed to reduce the fluctuation period, elucidating the intricate dynamics of the system. Analysis of the force response graphs revealed the presence of non-linear bifurcations, signifying critical transitions in the system's behavior. Notably, adjustments to the parameters of deviation from resonance and damping coefficient could transform critical bifurcations into safe ones, highlighting the potential for control and mitigation strategies. Furthermore, an examination of the frequency response demonstrated that increasing the linear frequency led to a decrease in non-linear stiffness and displacement at the starting points of non-linear bifurcations. This insight into the interplay between linear and non-linear dynamics sheds light on the system’s response to varying excitation conditions. Moreover, variations in excitation amplitude were found to induce changes in the starting points of non-linear bifurcations, underscoring the sensitivity of the system to external influences.

Overall, the findings underscore the complex interplay between parametric excitation, non-linear dynamics, and damping effects in beam vibrations. These insights have implications for the design and control of structures subjected to dynamic loading conditions, offering avenues for optimizing performance and mitigating undesirable responses.

Availability of data and materials

Data can be shared upon request.

References

Zhao L-C, Zou H-X, Zhao Y-J, Wu Z-Y, Liu F-R, Wei K-X, Zhang W-M (2022) Hybrid energy harvesting for self-powered rotor condition monitoring using maximal utilization strategy in structural space and operation process. Appl Energy 314:118983

Zhao L-C, Zou H-X, Wei K-X, Zhou S-X, Meng G, Zhang W-M (2023) Mechanical intelligent energy harvesting: from methodology to applications. Adv Energy Mater 13(29):2300557

Lu Z-Q, Liu W-H, Ding H, Chen L-Q (2022) Energy transfer of an axially loaded beam with a parallel-coupled nonlinear vibration isolator. J Vib Acoust 144(5):051009

Sheykhi M, Eskandari A, Ghafari D, Arpanahi RA, Mohammadi B, Hashemi SH (2023) Investigation of fluid viscosity and density on vibration of nano beam submerged in fluid considering nonlocal elasticity theory. Alex Eng J 65:607–614

Jing H, Gong X, Wang J, Wu R, Huang B (2022) An analysis of nonlinear beam vibrations with the extended Rayleigh-Ritz method. J Appl Comput Mech 8(4):1299–1306

Rezaee M, Javadian H, Maleki VA (2016) Investigation of vibration behavior and crack detection of a cracked short cantilever beam under the axial load. Amirkabir J Mech Eng 47(2):1–12

Ghaderi M, Ghaffarzadeh H, Maleki VA (2015) Investigation of vibration and stability of cracked columns under axial load. Earthq Struct 9(6):1181–1192

Rezaee M, Arab Maleki V (2019) Passive vibration control of the fluid conveying pipes using dynamic vibration absorber. Amirkabir J Mech Eng 51(3):111–120

Minaei M, ArabMaleki V (2020) Developing homotopy perturbation method to investigate the nonlinear vibration of a Porous FG-Beam subjected to the external excitation. J Sci Technol Compos 7(2):907–916

Jahanghiry R, Yahyazadeh R, Sharafkhani N, Maleki VA (2016) Stability analysis of FGM microgripper subjected to nonlinear electrostatic and temperature variation loadings. Sci Eng Compos Mater 23(2):199–207

Jahangiri G, Nabavian SR, Davoodi MR, Neya BN and Mostafavian S (2020) Effect of noise on output-only modal identification of beams. arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.10416.

Song H, Shan X, Li R, Hou C (2022) Review on the vibration suppression of cantilever beam through piezoelectric materials. Advanced Engineering Materials 24(11):2200408

Amer TS, Ismail AI, Amer WS (2023) Evaluation of the stability of a two degrees-of-freedom dynamical system. J Low Freq Noise Vib Active Control 42(4):1578–1595

Amer WS, Amer TS, Starosta R, Bek MA (2021) Resonance in the cart-pendulum system—an asymptotic approach. Appl Sci 11(23):11567

Abady IM, Amer TS, Gad HM, Bek MA (2022) The asymptotic analysis and stability of 3DOF non-linear damped rigid body pendulum near resonance. Ain Shams Eng J 13(2):101554

Amer WS, Amer TS, Hassan SS (2021) Modeling and stability analysis for the vibrating motion of three degrees-of-freedom dynamical system near resonance. Appl Sci 11(24):11943

Abdelhfeez SA, Amer TS, Elbaz RF, Bek MA (2022) Studying the influence of external torques on the dynamical motion and the stability of a 3DOF dynamic system. Alexandria Engineering Journal 61(9):6695–6724

Sharafkhani N, Kouzani AZ, Adams SD, Long JM, Orwa JO (2022) A pneumatic-based mechanism for inserting a flexible microprobe into the brain. J Appl Mech 89(3):031010

Sharafkhani N, Orwa JO, Adams SD, Long JM, Lissorgues G, Rousseau L, Kouzani AZ (2022) An intracortical polyimide microprobe with piezoelectric-based stiffness control. J Appl Mech 89(9):091008

Nasrabadi M, Sevbitov AV, Maleki VA, Akbar N, Javanshir I (2022) Passive fluid-induced vibration control of viscoelastic cylinder using nonlinear energy sink. Marine Structures 81:103116

Abohamer MK, Awrejcewicz J, Amer TS (2023) Modeling and analysis of a piezoelectric transducer embedded in a nonlinear damped dynamical system. Nonlinear Dyn 111(9):8217–8234

Abohamer MK, Awrejcewicz J, Amer TS (2023) Modeling of the vibration and stability of a dynamical system coupled with an energy harvesting device. Alex Eng J 63:377–397

Javidi R, Rezaei B, Moghimi Zand M (2023) Nonlinear dynamics of a beam subjected to a moving mass and resting on a viscoelastic foundation using optimal homotopy analysis method. Int J Struct Stab Dyn 23(08):2350084

Sedighi HM, Shirazi KH, Zare J (2012) An analytic solution of transversal oscillation of quintic non-linear beam with homotopy analysis method. Int J Non-Linear Mech 47(7):777–784

Liu T, Zheng HY, Zhang W, Zheng Y, Qian YJ (2024) Nonlinear forced vibrations of functionally graded three-phase composite cylindrical shell subjected to aerodynamic forces, external excitations and hygrothermal environment. Thin-Walled Struct 195:111511

Zheng Y, Zhang W, Liu T, Zhang YF (2022) Resonant responses and double-parameter multi-pulse chaotic vibrations of graphene platelets reinforced functionally graded rotating composite blade. Chaos Solitons Fract 156:111855

Liu T, Zhang W, Zheng Y, Zhang YF (2021) Andronov-Hopf bifurcations, Pomeau-Manneville intermittent chaos and nonlinear vibrations of large deployable space antenna subjected to thermal load and radial pre-stretched membranes with 1:3 internal resonance. Chaos Solitons Fract 144:110719

Liu T, Zhang W, Mao JJ, Zheng Y (2019) Nonlinear breathing vibrations of eccentric rotating composite laminated circular cylindrical shell subjected to temperature, rotating speed and external excitations. Mech Syst Signal Process 127:463–498

Mejia-Nava RA, Imamovic I, Hajdo E, Ibrahimbegovic A (2022) Nonlinear instability problem for geometrically exact beam under conservative and non-conservative loads. Eng Struct 265:114446

Ding H, Li Y, Chen L-Q (2019) Nonlinear vibration of a beam with asymmetric elastic supports. Nonlinear Dyn 95:2543–2554

Akkoca Ş, Bağdatli SM, Kara Toğun N (2022) Nonlinear vibration movements of the mid-supported micro-beam. Int J Struct Stab Dyn 22(14):2250174

Lewandowski R (2022) Nonlinear steady state vibrations of beams made of the fractional Zener material using an exponential version of the harmonic balance method. Meccanica 57(9):2337–2354

Sohani F, Eipakchi H (2023) Nonlinear geometry effects investigation on free vibrations of beams using shear deformation theory. Mech Based Design Struct Mach 51(3):1446–1467

Zamani H, Nourazar S and Aghdam M (2022) Large-amplitude vibration and buckling analysis of foam beams on nonlinear elastic foundations. Mech Time-Depend Mater 26(1):1–18.

Eldeeb AE, Zhang D, Shabana AA (2022) Cross-section deformation, geometric stiffening, and locking in the nonlinear vibration analysis of beams. Nonlinear Dyn 108(2):1425–1445

Zhang Z, Gao Z-T, Fang B, Zhang Y-W (2022) Vibration suppression of a geometrically nonlinear beam with boundary inertial nonlinear energy sinks. Nonlinear Dyn 109(3):1259–1275

Sedighi HM, Shirazi KH, Zare J (2012) Novel equivalent function for deadzone nonlinearity: applied to analytical solution of beam vibration using He’s Parameter Expanding Method. Latin Am J Solids Struct 9:443–452

Kim YC (1983) Nonlinear vibrations of long slender beams. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MA, USA.

Gonçalves PJP, Peplow A, Brennan MJ (2018) Exact expressions for numerical evaluation of high order modes of vibration in uniform Euler-Bernoulli beams. Appl Acous 141:371–373

Gonçalves P, Brennan M, Elliott S (2007) Numerical evaluation of high-order modes of vibration in uniform Euler-Bernoulli beams. J Sound Vib 301(3–5):1035–1039

Souri O, Mofid M (2023) Seismic evaluation of concentrically braced steel frames equipped with yielding elements and BRBs. Results Eng 17:100853

Saghafian M, Seyedzadeh H and Moradmand A (2023) Numerical simulation of electroosmotic flow in a rectangular microchannel with use of magnetic and electric fields. Scientia Iranica.

Razi S, Wang X, Mehreganian N, Tootkaboni M, Louhghalam A (2023) Application of mean-force potential lattice element method to modeling complex structures. Int J Mech Sci 260:108653

Khalafi M and Boob D (2023) Accelerated primal-dual methods for convex-strongly-concave saddle point problems. in International Conference on Machine Learning. 2023. Honolulu, Hawaii, USA.

Alizadeh MH, Ajri M, Maleki VA (2023) Mechanical properties prediction of ductile iron with spherical graphite using multi-scale finite element model. Physica Scripta 98(12):125270

Ahmadi H, Bayat A, Duc ND (2021) Nonlinear forced vibrations analysis of imperfect stiffened FG doubly curved shallow shell in thermal environment using multiple scales method. Compos Struct 256:113090

Pourreza T, Alijani A, Maleki VA, Kazemi A (2022) The effect of magnetic field on buckling and nonlinear vibrations of Graphene nanosheets based on nonlocal elasticity theory. Int J Nano Dimens 13(1):54–70

Pourreza T, Alijani A, Maleki VA, Kazemi A (2021) Nonlinear vibration of nanosheets subjected to electromagnetic fields and electrical current. Adv Nano Res 10(5):481–491

Kevorkian JK and Cole JD. (2012) Multiple scale and singular perturbation methods. Vol. 114. Springer Science & Business Media, New York, USA.

Nayfeh AH and Mook DT (2008) Nonlinear oscillations. Wiley, Germany.

Barari A, Kaliji HD, Ghadimi M, Domairry G (2011) Non-linear vibration of Euler-Bernoulli beams. Latin Amn J Solids Struct 8:139–148

Nayfeh AH and Balachandran B (2008) Applied nonlinear dynamics: analytical, computational, and experimental methods. Wiley, Germany.

Acknowledgements

I would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge that there are no individuals or organizations that require acknowledgment for their contributions to this work.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author contributed to the study’s conception and design. Data collection, simulation, and analysis were performed by Pengtai Liao.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, P. Non-linear vibration and bifurcation analysis of Euler-Bernoulli beam under parametric excitation. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 71, 85 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-024-00420-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-024-00420-y