Abstract

Background

Worldwide, bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, and chronic rhinosinusitis are highly prevalent conditions, and numerous researches have shown how they affect one another. Still, reports about surgical treatments remain limited.

Aim

To investigate the role of functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) with posterior nasal nerve/vidian neurectomy, as a surgical protocol in the management of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP), and its effect on bronchial asthma (BA) patients’ quality of life and pulmonary function tests.

Methods

This study was a prospective observational study that involved 25 patients with BA and CRSwNP who underwent full-house FESS with bilateral posterior nasal nerve or vidian neurectomy in the Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Department and were evaluated in the Chest Department, Zagazig University, from May 2022 to December 2023. All included patients were subjected to pre- and post-operative respiratory assessments including spirometry, Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ), and Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ). Also, all patients were subjected to pre- and post-operative nasal assessment including visual analog scale (VAS), nasal endoscopic evaluation, and routine CT paranasal sinus.

Results

This study included 25 patients (11 men and 14 women; age range 18–57 years; mean ± SD of age 33.24 ± 11.3 years). There were statistically significant increases as regards forced vital capacity and forced expiratory volume in 1 s according to preoperative, 3 months, and 6 months postoperative values. As regards ACQ, AQLQ, and VAS scores, there were highly statistically significant improvements according to preoperative, 3 months, and 6 months postoperative follow-up scores. Asthma medication step-down was successful in 52% of patients after 6 months of follow-up.

Conclusions

The quality of life, pulmonary function, and nasal symptoms of people with bronchial asthma combined with CRSwNP can both be alleviated after posterior nasal nerve/vidian neurectomy beside FESS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the “united airway disease” idea was first proposed, numerous researches have shown that bronchial asthma (BA), allergic rhinitis (AR), and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) are co-occurring conditions [1].

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP), which is a refractory type of CRS, is more likely to be associated with asthma than those with CRS without nasal polyposis (CRSsNP). Approximately 20–60% of CRSwNP patients have comorbid asthma [2].

CRSwNP with concurrent asthma can lead to more significant sinonasal manifestations and poor quality of life. It is also more challenging to manage, either medically or surgically [3]. In addition to being more difficult to manage, asthma with nasal polyposis is associated with increased airway narrowing, prominent eosinophilic inflammation, greater rates of corticosteroid dependency, and exacerbation proneness [4].

Medical therapy has the potential to alleviate CRSwNP symptoms, which in turn improves BA manifestation. CRSwNP necessitates surgical intervention to control nasal allergy prior to medical therapy [5]. Bilateral endoscopic vidian neurectomy (VN)–posterior nasal nerve neurectomy (PNN) is a surgical technique to manage severe vasomotor rhinitis and AR patients without evident effect on overactive airway and BA [6,7,8].

This study aims to investigate the role of functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) with posterior nasal nerve/vidian neurectomy, as a surgical protocol in the management of CRSwNP, and its effect on BA patient QoL and pulmonary function tests.

Patients and methods

Patient selection and study design

This was a prospective observational study conducted on 25 patients with CRSwNP and BA who underwent surgical intervention (as a comprehensive sample) in the Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (ORL-HNS) Department and were assessed in the Chest Department, Zagazig University, from December 2022 to November 2023. This study was approved by the institutional board review of Zagazig University and their permission number was (ZU-IRB #9954/5–10-2022). This human subject’s research was carried out in accordance with the World Medical Association’s code of ethics, the Helsinki Declaration. Informed and signed consent was obtained from the patients who were recruited for this study.

The inclusion criteria were adult patients (≥ 18 years old) with CRS endo-type 2 (IgE > 100 IU/ml) with bilateral ethmoidal polypi and had concomitant bronchial asthma with type 2 inflammation followed the Global Initiative for Asthma Recommendations (GINA) [9]. The exclusion criteria were cases with CRSsNP, any other respiratory conditions, muco-ciliary disorders, and patients on immunotherapy.

Operational design

Preoperative evaluation

All included patients were subjected to pre-operative respiratory assessment including the following:

-

1.

Pulmonary function tests (PFT): forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) were measured by using a spirometer device (Spirotube, IDEGEN TECHNOLOGY, Hungary) in the Chest Outpatient Clinic, Zagagzig University Hospitals. Airflow limitation was assessed according to GINA [9]. Airflow limitation is proven when FEV1/FVC is decreased in comparison with the lower limit of normal (which is often in adults > 0.75–0.80), and post-bronchodilator responsiveness assessed to confirm the diagnosis of BA. FEV1 was assessed shortly after inhalating a rapid-acting bronchodilator like 200–400 mcg salbutamol. If FEV1 increase by more than 12% and 200 mL (higher confidence if the increase is more than 15% and 400 mL), post-bronchodilator resposiveness was proven [9].

-

2.

Questionnaires:

-

(a)

Asthma control assessment was done using asthma control questionnaire (ACQ) “score ranges from 0 to 6; higher score corresponds to lower satisfaction.” ACQ ≤ 0.75 suggested a high likelihood of well-controlled asthma; 0.75–1.5 as a “gray zone”; and ≥ 1.5 suggested a high likelihood of poorly controlled asthma [9].

-

(b)

Quality of life was assessed by the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ): There were 15 items total in the mini-AQLQ divided into 4 domains: activity limitation (four components), symptoms (five components), emotional function (three components), and environmental stimuli (three components). Each component is evaluated on a 7-point rating system, with a higher score denoting higher health-related QoL. The mean score, which was determined by multiplying the total score by the number of items, is the main outcome of the mini-AQLQ, and the domain scores were determined by dividing the overall score by the number of items in each domain. A difference of at least 0.5 was deemed clinically significant [10].

-

(c)

Assessment of medications before surgery was done.

-

(a)

All included patients were subjected to pre-operative nasal assessment including:

-

Patient quality of life QoL was addressed by visual analog scale (VAS) regarding nasal allergic symptoms (sneezing-itching-rhinorrhea-congestion/obstruction) symptom “score ranges from 0 to 10”

-

Nasal endoscopic evaluation

-

Routine CT paranasal sinus (PNS)

Surgical technique

Full house FESS was done to all patients.

Bilateral posterior nasal neurectomy or vidian neurectomy (according to surgeon preference). When vidian neurectomy was adopted, a retrograde approach was selected. The retrograde approach aimed to expose the vidian nerve within the pterygopalatine fossa (PPF) where the surgeon cut the continuity of the vidian nerve and cauterized its stump. Sphenopalatine artery (SPA) was ligated if the course of artery crossing nerve emerging point. In this situation with ligation of SPA on one side, the other side posterior nasal neurectomy was applied instead of vidian neurectomy.

Postoperative

Postoperative nasal wash by saline-steroid (budesonide), postoperative systemic steroid with tapering dose over 3 weeks then continue on nasal steroid sprays. Asthma treatment was prescribed according to the asthma global recommendation.

The follow-up regimen included weekly nasal endoscopy till healing of nasal mucosa then monthly till 6 month postoperative period finally annually.

Postoperative pulmonary function test (FVC and FEV1), ACQ, AQLQ, VAS, and asthma medication were evaluated 3–6 months after surgical intervention to be compared by preoperative values. Step down of asthma treatment was done according to GINA [9].

Statistical analysis

Both IBM SPSS 23.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and NCSS 11 for Windows (NCSS LCC., Kaysville, UT, USA) were used to analyze the data. Quantitative parameters were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Qualitative parameters were expressed as frequency and percentage (%). The normality of the data was checked using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

The following tests were done:

-

Repeated measure ANOVA (F) test to assess the significance of change in quantitative data over many times.

-

Friedman test for change in percent (qualitative data) over multiple assessments.

-

Wilcoxon signed rank test for comparison of paired not normally distributed quantitative data.

-

Probability (P-value): P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant, P-value ≤ 0.001 was considered as highly significant, and P-value > 0.05 was considered insignificant.

Results

This study included 25 patients (11 men and 14 women; age range 18–57 years; mean ± SD of age 33.24 ± 11.3 years) with CRSwNP and bronchial asthma (endo-type 2). Fifteen (60%) patients were cigarette smokers, 11 (44%) patients had moderate asthma, and 14 (56%) patients had severe asthma. Patients had a history of asthma with a duration of 8.38 ± 7.21 years as shown in Table 1.

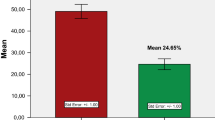

Table 2 shows the change in PFT and ACQ score over follow-up time. There were statistically significant improvements as regards FVC and FEV1 according to preoperative, 3 months and 6 months postoperative values (P-value 0.01 and 0.009, respectively). As regards ACQ score, there was a highly statistically significant decrease according to preoperative, 3 months and 6 months postoperative follow-up scores (P-value < 0.001). Pre-operation, 44% of patients were poorly controlled versus 4% and 0% 3 months and 6 months postoperative, respectively. Fifty-six percent of patients were well controlled 6 months post-operation versus 8% and 0% 3 months post-operation and pre-operation, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Changes in AQLQ score over the follow-up period were introduced in Table 2. It showed highly statistically significant improvement regarding symptoms and emotional stimuli domains (P-value < 0.001), but no statistically significant difference as regards environmental stimuli (P-value = 0.201) over the follow-up period. As regards activity limitations, it showed a statistically significant difference over the follow-up period (P-value = 0.01). The total score of AQLQ showed a highly statistically significant improvement over the follow-up period (P-value < 0.001).

Table 3 illustrated the changes in the VAS score of nasal symptoms pre- and post-operation. It showed highly statistically significant differences as regards sneezing, itching, rhinorrhea, and congestion (P-value < 0.001).

Asthma medication step-down after 6 months of follow-up was illustrated in Fig. 2. Step-down was successful in 52% of patients.

Discussion

Numerous researches established a shared pathogenesis—either a hematogenic, neurogenic, or mechanical connection—between AR, CRS, and asthma [11], such as the mouth breathing effect, the nasal-bronchial reflex, and postnasal inflammatory secretion, which resulted in inhaled air that was neither filtered nor humidified nor had its temperature adjusted [12].

When compared to individuals with asthma alone, patients with CRSwNP make asthma harder to manage because it causes more airway obstruction, more widespread eosinophilic inflammation, and increases the risk of exacerbations [13]. Treatment choices enable the management of rhinitis and asthma concurrently, and rhinitis control promotes asthma control [8].

AR and CRS intervention would be valuable to asthma management. But currently, several studies concentrate on the alterations of PFT in AR patients and CRS patients, and there is a dearth of research on early intervention, particularly surgical interference [8].

Nasal cavity secretion has been shown to increase in response to pterygoid nerve stimulation. Additionally, allergens have the ability to cause central sensitization to stimulation of the nasal mucosa. This intensifies the local inflammatory response in the nasal mucosa by causing efferent neurons to release more neuropeptides and other chemicals. Thus, in patients with AR, a “vicious circle” of allergen stimulation, central sensitization, elevated neuroreactivity, and enhanced inflammatory response may develop. Because of this, VN may regulate airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) and pulmonary function by modulating inflammatory mediators [8].

With the advancement of endoscopic endonasal surgery, posterior nasal nerve neurectomy replaced the traditional vidian neurectomy. This minimally invasive procedure resolved the complications associated with vidian neurectomy [14].

Our study aimed to investigate the role of FESS with posterior nasal nerve/vidian neurectomy, as a surgical protocol in the management of CRSwNP, and its effect on BA patients’ QoL and PFT.

PNN are the terminal branches of the vidian nerve, so technically, PNN neurectomy is quite easier than VN. On the other hand, VN provides sure autonomic denervation of nasal mucosa especially when the surgeon missed one of two terminal branches of PNNs. In short, autonomic nasal neurectomy is planned for PNNs neurectomy, if there is quite an uncertainty to accomplish complete neurectomy, VN is recommended. By the previously mentioned surgeon protocol, denervation is ensured with similar postoperative results.

Because of the reduction in residual volume and increase in airway diameter that occurs in response to asthma medication, both FEV1 and FVC improve. As a result, even with successful treatment, the FEV1/FVC ratio may show little to no difference [15].

In our study, we assessed FVC and FEV1, and the results confirmed statistically significant improvement in 3 months and 6 months post-operation values in comparison with preoperative values. Similar results were proved by Maimaitiaili et al. [8] and found that the number of AR and CRSwNP patients with pulmonary function impairment or AHR was significantly decreased following endoscopic nasal polypectomy, sinus open surgery accompanied with vidian neurectomy in comparison with patients treated with the endoscopic nasal polypectomy, sinus open surgery alone. The study revealed a considerable reduction in eosinophilic cationic protein (ECP) levels in a time-dependent manner following surgery. There was also a notable drop in IgE levels following vidian neurectomy.

Additionally, some researches have shown that there were various roles of ECP from eosinophils including lowering mucous clearance, altering the composition of airway fluid, causing damage to the exfoliation of the airway epithelium leading to exposure of sensory nerve endings, encouraging pore formation, and raising mucosal permeability, which exacerbates BA and impairment of lung function [16].

We also reported in our study that asthma control level that was evaluated by ACQ was highly statistically significantly improved over follow-up period. Regarding asthma QoL, we proved a highly statistically significant improvement over follow-up period. The significant improvement was found as regards asthma symptoms, emotional function, and activity limitation with no significant improvement as regards environmental stimuli.

The same finding was proved by Ai and colleagues [17] that VN for patients with refractory AR with asthma resulted in not only patients’ AR QoL improvement but also to asthma QoL improvement. Even so, patients’ AR QoL improved at a rate that was significantly greater than their asthma QoL. They discovered that while local surgical treatment of AR did not significantly benefit patients whose asthma attack was triggered by upper respiratory infections, food allergies, emotions, exercise, or smoking, 64% (16/25) of patients whose asthma attack was triggered on by weather changes benefited from VN treatment of rhinitis.

Also, Qi et al. [18] in their study about the efficacy of selective VN showed that patients who were enrolled in AR and had asthma also completed follow-up observations for 2 years without experiencing any more asthma attacks.

Endoscopic sinus surgery has been shown by Chen et al. [19] to consistently enhance the level of control of asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis, but not pulmonary function.

Ma et al. [20] reported that VN inhibited the expression of many cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-5. These cytokines function as selective chemoattractants and activators, promoting the aggregation, proliferation, activation, and ECP release of eosinophils.

Ogawa et al. [21] discovered that PNN considerably lowers eotaxin protein and IL-5 levels in nasal secretions in patients with allergic rhinitis. Additionally, they noticed a decrease in the subepithelial mucous layer’s infiltrated immune component cells, which are important sources of cytokine release.

We succeeded to step down asthma medication 6 months post-operation in more than half of the patients included in our study.

A compelling support to our results was introduced by Ai and colleagues [17] who reported a significant decrease in medication scores for AR, and asthma was detected at 6 months, 1 year, and 3 years after VN, but no significant change was noticed in the control group (received medical therapy alone).

Allergic rhinitis symptoms showed a statistically significant reduction between preoperative assessment and after 6 months following FESS with posterior nasal neurectomy/vidian neurectomy. The assessment was achieved via the VAS score of allergic rhinitis (sneezing, itching, rhinorrhea, and nasal congestion) (P-value < 0.001). Each symptom revealed a reduction ≥ 2 in VAS which was considered a significant reduction [22]. While posterior nasal vidian neurectomy may disrupt the allergen stimulation vicious cycle, central sensitization, and neuroreactivity, FESS combined with intranasal polypectomy may alleviate nasal congestion-nasal obstruction and hence lessen rhinorrhea with a decrease in inflammatory burden [8]. This had an agreement with Trivedi and his colleague [7] who declared a significant reduction in allergic symptoms by the end of the 6th postoperative month 70.2% reduction/average 3.4 average in total nasal symptom score (TNSS).

Unfortunately, dry eye is a possible complication in vidian neurectomy which is present in 20% of cases (including 25 patients = 15 patients who undergone bilateral PNN neurectomy, 10 patients who undergone unilateral PNN neurectomy, another side vidian neurectomy) of those who undergone unilateral vidian neurectomy, 5 patients complained of initial dry eye, 3 patients resolved after 6 weeks follow-up, and the remaining 2 patients had persistent dry eye which need fresh tear application.

Tan et al. [6] revealed that dry eye was the most reported complication in patients who underwent bilateral endoscopic vidian neurectomy which was resolved after 1 month of treatment with sodium hyaluronate eye drops. Mild nasal dryness and upper lip/palate numbness were also reported complications.

PNN reduces the possibility of vidian neurectomy-related irreversible side effects such as persistent dry eye and palate numbness [23].

One of our study’s shortcomings is that there was no nonsurgical control group. Second, the quantities of type 2 cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, in the sputum and serum were not measured, and many features of the underlying cytokine network in the upper and lower airway are still unclear. Thirdly, serum IgE was only assessed at baseline; it was not measured during the same time frame in the previous year in our research. Consequently, it is indisputable that our results were impacted by seasonal variations in serum IgE. This study addresses the outcome of the vidian nerve/PNN neurectomy during the 3–6 months postoperative period. Further studies are needed to evaluate the long-term effect of autonomic denervation either in terms of advantages or complications.

Conclusion

The quality of life, pulmonary function, and nasal symptoms of people with bronchial asthma combined with CRSwNP can both be alleviated after posterior nasal nerve/vidian neurectomy beside FESS.

Availability of data and materials

The corresponding author can give the database that was used and examined in this study upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACQ:

-

Asthma Control Questionnaire

- AHR:

-

Airway hyperresponsiveness

- AQLQ:

-

Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire

- AR:

-

Allergic rhinitis

- BA:

-

Bronchial asthma

- CRS:

-

Chronic rhinosinusitis

- CRSsNP:

-

Chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyposis

- CRSwNP:

-

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis

- ECP:

-

Eosinophilic cationic protein

- FESS:

-

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery

- FEV1 :

-

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- GINA:

-

Global Initiative for Asthma Recommendations

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- ORL-HNS:

-

Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery

- PFT:

-

Pulmonary function tests

- PNN:

-

Posterior nasal nerve neurectomy

- PNS:

-

Paranasal sinus

- PPF:

-

Pterygopalatine fossa

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- SPA:

-

Sphenopalatine artery

- TNSS:

-

Total nasal symptom score

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- VN:

-

Vidian neurectomy

References

Chandrika D (2017) Allergic rhinitis in India: an overview. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 3(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.18203/issn.2454-5929.ijohns20164801

Promsopa C, Kansara S, Citardi MJ, Fakhri S, Porter P, Luong A (2016) Prevalence of confirmed asthma varies in chronic rhinosinusitis subtypes. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 6(4):373–377. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.21674

Laidlaw TM, Mullol J, Woessner KM, Amin N, Mannent LP (2021) Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 9(3):1133–1141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.09.063

Stevens WW, Peters AT, Hirsch AG, Nordberg CM, Schwartz BS, Mercer DG et al (2017) Clinical characteristics of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, asthma, and aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 5(4):1061–1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2016.12.027

Halderman A, Sindwani R (2015) Surgical management of vasomotor rhinitis: a systematic review. Am J Rhinol Allergy 29(2):128–134. https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2015.29.4141

Tan G, Ma Y, Li H, Li W, Wang J (2012) Long-term results of bilateral endoscopic vidian neurectomy in the management of moderate to severe persistent allergic rhinitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 138(5):492–497. https://doi.org/10.1001/archoto.2012.284

Trivedi B, Vyas P, Soni NK, Gupta P, Dabaria RK (2022) Is posterior nasal nerve neurectomy really a ray of hope for the patients of allergic rhinitis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 74(Suppl 3):4713–4717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-021-03031-8

Maimaitiaili G, Kahaer K, Tang L, Zhang J (2020) The effect of vidian neurectomy on pulmonary function in patients with allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Am J Med Sci 360(2):137–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjms.2020.04.024

Global initiative for Asthme (GINA) (2022) Global strategy for asthma management and prevention, NHLBI/WHO workshop report. https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/

Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR (1999) Development and validation of the mini asthma quality of life questionnaire. Eur Respir J 14(1):32–38. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a08.x

McCusker CT (2004) Use of mouse models of allergic rhinitis to study the upper and lower airway link. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 4(1):11–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/00130832-200402000-00004

Tan RA, Corren J (2011) The relationship of rhinitis and asthma, sinusitis, food allergy, and eczema. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 31(3):481–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2011.05.010

Langdon C, Mullol J (2016) Nasal polyps in patients with asthma: prevalence, impact and management challenges. J Asthma Allergy 9:45–53. https://doi.org/10.2147/JAA.S86251

Kawamura S, Asako M, Momotani A, Kedai H, Kubo N, Yamashita T (2000) Submucosal turbinectomy with posterior-superior nasal neurectomy for patients with allergic rhinitis. Pract Oto Rhino Laryngol 93(5):367–372. https://doi.org/10.5631/jibirin.93.367

Tepper RS, Wise RS, Covar R, Irvin CG, ChG KCM, Kraft M, Liu MC, O’Connor GT, Peters SP, Sorkness R, Togias A (2012) Asthma outcomes: pulmonary physiology. J Allergy Clin Immunol 129(30):S65–S87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.986

Guo CL, Sun XM, Wang XW et al (2017) Serum eosinophil cationic protein is a useful marker for assessing the efficacy of inhaled corticosteroid therapy in children with bronchial asthma. Tohoku J Exp Med 24(4):263–271. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.242.263

Ai J, Xie Z, Qing X, Li W, Liu H, Wang T, Tan G (2018) Clinical effect of endoscopic vidian neurectomy on bronchial asthma outcomes in patients with coexisting refractory allergic rhinitis and asthma. Am J Rhinol Allergy 32(3):139–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/1945892418764964

Qi Y, Liu J, Peng S, Hou S, Zhang M, Wang Z (2021) Efficacy of selective vidian neurectomy for allergic rhinitis combined with chronic rhinosinusitis. Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 83(5):327–334. https://doi.org/10.1159/000512083

Chen FH, Zuo KJ, Guo YB et al (2014) Long-term results of endoscopic sinus surgery-oriented treatment for chronic rhinosinusitis with asthma. Laryngoscope 124(1):24–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24196

Ma Y, Tan G, Zhao Z et al (2014) Therapeutic effectiveness of endoscopic vidian neurectomy for the treatment of vasomotor rhinitis. Acta Otolaryngol 134(3):260–267. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016489.2013.831478

Ogawa T, Takeno S, Ishino T, Hirakawa K (2007) Submucous turbinectomy combined with posterior nasal neurectomy in the management of severe allergic rhinitis: clinical outcomes and local cytokine changes. Auris Nasus Larynx 34(3):319–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2007.01.008

Zeldin Y, Weiler Z, Magen E, Tiosano L, Iancovid Kidon M (2008) Safety and efficacy of allergen immunotherapy in the treatment of allergic rhinitis and asthma in real life. Isr Med Assoc J 10(12):869–872

Hua H, Wang G, Zhao Y, Wang D, Qiu Z, Fang P (2022) The long-term outcomes of posterior nasal neurectomy with or without pharyngeal neurectomy in patients with allergic rhinitis: a randomized controlled trial. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 88(S1):S147–S155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2021.05.006

Acknowledgements

The researchers are pleased to acknowledge every one of the investigators and participants.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding organizations in the public, commercial, or non-commercial sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HAE: collection of the data and writing of the manuscript. MM: selection of the study subject and supervision. AE: supervision of the research. MAA: practical part of the study. AHS: writing of the manuscript and practical part of the study. MEE: practical part of the study. All authors have read and accepted the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was permitted by the institutional board review of Zagazig University (ZU-IRB #9954/5-10-2022). Informed and signed consent was given by patients who were included in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elshahaat, H.A., Mobashir, M., Elhawary, A. et al. The outcome of posterior nasal nerve/vidian nerve neurectomy during FESS on patients of nasal polyposis associated with bronchial asthma. Egypt J Bronchol 18, 36 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43168-024-00289-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43168-024-00289-8