Abstract

Background

Tracheobronchial injuries generally occur due to iatrogenic or traumatic causes. Although bronchial rupture due to teratoma and germ cell tumors has been reported in the literature, no cases related to lung cancer have been determined. Our case is presented because of the refusal to be examined for the mass in the lung and the detection of bronchial rupture afterward when he presented with massive hemoptysis.

Case presentation

A 65-year-old male patient was admitted to the emergency department with the complaint of massive hemoptysis. Six months ago, bronchoscopy was recommended due to the 8 × 7 cm cavitary lesion obliterating the bronchus in the anterior upper lobe of the right lung on chest computed tomography, but the patient refused. The sputum sample, requested 3 times, was negative for acid-resistant bacteria, and no growth was detected in the mycobacterial culture. In the new pulmonary CT angiography, a progressive cavitary lesion invading the right main bronchus, carina, and vena cava superior was observed. Following tranexamic acid treatment and bronchial artery embolization, hemoptysis significantly decreased in the follow-up. In the flexible bronchoscopy performed for diagnostic purposes, the carina was pushed to the left and invaded, and there was damage to the right main bronchus. A biopsy was not performed due to the risk of bleeding, and lavage was performed. Lavage was negative for ARB, there was no growth in the mycobacteria culture, and cytology did not reveal malignant cells. The patient, diagnosed with right main bronchial rupture, was considered inoperable and died 1 month later due to respiratory failure.

Conclusions

Examinations should be initiated as soon as malignancy is suspected. When diagnosis and treatment are delayed, complications that would be challenging to intervene may develop.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lung cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer type with the most mortal clinical course [1]. Symptoms in lung cancer emerge depending on the primary tumor and its intrathoracic spread, the presence of distant metastases, and the development of paraneoplastic syndrome [2]. However, the occurrence of massive hemoptysis as a result of a bronchial rupture is extremely rare. Our case, which was observed to have bronchial rupture when he presented with massive hemoptysis 6 months after refusing an examination for his lung mass, is presented to emphasize that it should not be delayed in diagnosing and treating cancer since bronchial artery embolization was performed. However, only palliative care could be recommended due to the inoperable cancer stage.

Case presentation

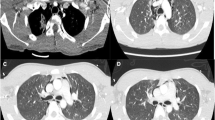

A 65-year-old male patient was admitted to the outpatient clinic complaining of cough, sputum, dyspnea, and chest pain. He had a 40-pack-year history of smoking and was an active smoker. On physical examination, respiratory sounds were decreased in the upper zone of the right lung. Because of the 8 × 7 cm cavitary lesion obliterating the bronchus in the anterior upper lobe of the right lung on chest computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 1), bronchoscopy was planned with the preliminary diagnoses of lung cancer and tuberculosis, but the patient refused. The results from three samples of sputum acid-resistant bacteria (ARB) were negative, and there were no growths in mycobacteria cultures. Six months later, he was admitted to the emergency department with the complaint of massive hemoptysis (approximately 200 cc/day). The pulmonary CT angiography revealed a cavitary lesion, which progressed when compared to the previous examination, invading the right main bronchus, carina, and vena cava superior (Fig. 2). Tranexamic acid treatment was initiated, and the patient was hospitalized in the intensive care unit. Bronchial artery embolization was performed by the interventional radiology department (Fig. 3). Following the embolization procedure, the hemoptysis significantly decreased in the follow-ups. In the flexible bronchoscopy performed for diagnostic purposes, it was observed that the carina was pushed to the left, and there was damage to the right main bronchus with an invasive appearance (Fig. 4). A biopsy was not performed due to the risk of bleeding, and lavage was performed. ARB analysis was negative in the lavage sample, there was no growth in the mycobacterial culture, and no malignant cells were determined in the cytology. The patient was diagnosed with right main bronchus rupture and was considered inoperable since the mass invaded the vena cava superior, proximal right main bronchus, and carina. The patient died one month later due to respiratory failure.

a In the angiogram performed from the right costo-bronchial artery, an appearance compatible with anarchic vascularity in the localization that fits around the cavitary lesion. b After embolization with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) polymer, it is observed that the anarchic vascularity is lost, and the flow is stagnated

Discussion and conclusion

Tracheobronchial injuries (TBI) are rarely observed, and their frequency remains unclear since approximately 80% of the patients die before hospital admission [3, 4]. Most TBIs are iatrogenic or traumatic [5, 6]. It is infrequent for the tumor to rupture the bronchus secondary to direct bronchial invasion. Cases secondary to mediastinal teratoma and germ cell tumor have been reported in the literature, and no rupture due to direct lung cancer has been determined [7,8,9]. In our case, bronchial rupture developed secondary to the mass in the lung without any trauma or iatrogenic cause, but a pathological diagnosis could not be made since no biopsy was performed.

The risk of bronchial rupture increases in intubation with a double-lumen endotracheal tube, frequently used in major thoracic surgery operations [5]. Tracheobronchial injury can also develop due to reasons such as requiring more endobronchial tube manipulation than open thoracotomy during thoracoscopy, collapsed lungs due to carbon dioxide inflation, excessive torsion in the airways, and delayed diagnosis because the procedure is performed in a dark room [5]. Yüceyar et al. reported that only one case of tracheobronchial laceration developed in 900 double-lumen tube intubations [6]. Regarding gender, it has been reported that it most frequently develops in females [10]. The most common site of rupture is the left main bronchus, probably due to the anesthetists’ intubation of the left main bronchus independent of the thoracotomy site and the distal narrowing of the left main bronchus [11]. However, in our case, the bronchial rupture was observed in the right main bronchus because the mass was also on the right.

As a result of bronchial rupture, mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema (87%), pneumothorax (17-70%), atelectasis, mediastinitis, sepsis, and mortal course may occur [5, 6, 12]. Although the most common symptoms are chest pain, shortness of breath, cough, and fever, hemoptysis may also develop [8, 13]. In our case, massive hemoptysis emerged, and bleeding could only be stopped by bronchial artery embolization.

The significance of computed tomography (CT) in diagnosing TBI is that it can reveal mediastinal emphysema, mediastinal hematoma, and related major vessel injuries that cannot be detected with chest radiography. In the presence of TBI suspicion, even if the CT is normal, the diagnosis should be achieved by performing flexible or rigid bronchoscopy [14]. Bronchoscopic findings include rupture of the bronchial wall, blood in the airway, and collapsed airway with the inability to see and access the distal part of the injury site [15]. In our case, the diagnosis was made with CT and flexible bronchoscopy, which was performed afterward.

Clinical, radiological, and endoscopic findings are determinative in TBI treatment decisions. Conservative treatment is preferred for patients whose laceration is small (less than approximately 2 cm) and suitable for adequate cuff position, or for lacerations that do not involve the entire thickness of the tracheobronchial wall, and for patients who are in poor general condition and at very high surgical risk [16]. In patients other than these, the treatment is surgical, if possible, as soon as the diagnosis is made. The surgical approach can be cervical or posterolateral thoracotomy, depending on the location of the injury [15]. While minor tears and lacerations can be primarily repaired, complete or partial transections require debridement of infected and devitalized tissue, cutting the edges of the injured airway, and end-to-end anastomosis [3, 15]. The literature has also reported that successful outcomes were obtained with minimally invasive robotic-assisted sleeve surgery in a patient who presented with traumatic left main bronchus rupture [17]. If there is extensive bronchial damage, concomitant pulmonary vascular damage, or irreversible lung parenchymal damage, lung resection may be required to effectively control the injury [12]. Gabor et al. reported that when 29 of 31 patients with iatrogenic or traumatic tracheobronchial rupture were treated surgically, and two were treated conservatively, four postoperatively died due to sepsis unrelated to TBI, while the other patients recovered [18]. Conservative treatment includes intubation with the cuff placed distal to the tear, chest tube drainage if necessary, and antibiotic therapy [18]. There are also cases where extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was used in cases of traumatic bronchial rupture [19]. High ventilation pressures should be avoided. High mortality rates in conservatively treated cases can be explained by the worsening general condition of these patients [18].

The reported case was considered inoperable since the mass invaded the superior vena cava, proximal right main bronchus, and carina, and only palliative care was recommended. When there is a delay in diagnosing and treating TBI, airway stenosis or complete bronchial obstruction may develop because the injured bronchus is filled with fibro-granulation tissue and organized hematoma. The case also died 1 month after the diagnosis of bronchial rupture due to respiratory failure.

When the diagnosis and treatment of malignancy are delayed, it should be kept in mind that the patient may be deprived of available treatment options.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ARB:

-

Acid-resistant bacteria

- TBI:

-

Tracheobronchial injuries

- ECMO:

-

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

References

Li C, Lei S, Ding L, Xu Y, Wu X, Wang H, Zhang Z, Gao T, Zhang Y, Li L (2023) Global burden and trends of lung cancer incidence and mortality. Chin Med J (Engl) 136(13):1583–1590. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000002529

Beckles MA, Spiro SG, Colice GL, Rudd RM (2003) Initial evaluation of the patient with lung cancer: symptoms, signs, laboratory tests, and paraneoplastic syndromes. Chest 123(1 Suppl):97S-104S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.97s

Kiser AC, O’Brien SM, Detterbeck FC (2001) Blunt tracheobronchial injuries: treatment and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 71(6):2059–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02453-x

Kummer C, Netto FS, Rizoli S, Yee D (2007) A review of traumatic airway injuries: potential implications for airway assessment and management. Injury 38(1):27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2006.09.002

Gilbert TB, Goodsell CW, Krasna MJ (1999) Bronchial rupture by a double-lumen endobronchial tube during staging thoracoscopy. Anesth Analg 88(6):1252–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000539-199906000-00012

Yüceyar L, Kaynak K, Cantürk E, Aykaç B (2003) Bronchial rupture with a left-sided polyvinylchloride double-lumen tube. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 47(5):622–5. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00102.x

Anderson JE, Taylor MR, Romberg EK, Riehle KJ, Kapur R, Crocker ME, Crotty EE, Hergenroeder G, Greenberg SL (2022) Mature mediastinal teratoma with tumor rupture into airway. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep 81:102270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsc.2022.102270

Suzuki H, Koh E, Hoshino I, Kishi H, Saitoh Y (2010) Mediastinal teratoma complicated with acute mediastinitis. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 58(2):105–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11748-009-0487-0

Sasaka K, Kurihara Y, Nakajima Y, Seto Y, Endo I, Ishikawa T, Takagi M (1998) Spontaneous rupture: a complication of benign mature teratomas of the mediastinum. AJR Am J Roentgenol 170(2):323–8. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.170.2.9456938

Fitzmaurice BG, Brodsky JB (1999) Airway rupture from double-lumen tubes. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 13(3):322–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1053-0770(99)90273-2

Hannallah M, Gomes M (1989) Bronchial rupture associated with the use of a double-lumen tube in a small adult. Anesthesiology 71(3):457–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-198909000-00027

Koletsis E, Prokakis C, Baltayiannis N, Apostolakis E, Chatzimichalis A, Dougenis D (2012) Surgical decision making in tracheobronchial injuries on the basis of clinical evidences and the injury’s anatomical setting: a retrospective analysis. Injury 43(9):1437–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.038

Yang WM, Chen ML, Lin TS (2005) Traumatic hemothorax resulting from rupture of mediastinal teratoma: a case report. Int Surg 90(4):241–4

Welter S, Hoffmann H (2013) Verletzungen des Tracheobronchialbaums [Injuries to the tracheo-bronchial tree]. Zentralbl Chir 138(1):111–6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1328269. German. Epub 2013 Feb 28

Prokakis C, Koletsis EN, Dedeilias P, Fligou F, Filos K, Dougenis D (2014) Airway trauma: a review on epidemiology, mechanisms of injury, diagnosis and treatment. J Cardiothorac Surg 9:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-8090-9-117

Schultz SC, Hammon JW Jr, Turner CS, McGuirt WF Jr, Nelson JM (1999) Surgical management and follow-up of a complex tracheobronchial injury. Ann Thorac Surg 67(3):834–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-4975(98)01206-5

Wang HC, How CH, Lin HF, Lee JM (2017) Traumatic left main bronchial rupture: delayed but successful outcome of robotic-assisted reconstruction. Respirol Case Rep 6(1):e00278. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcr2.278

Gabor S, Renner H, Pinter H, Sankin O, Maier A, Tomaselli F, SmolleJüttner FM (2001) Indications for surgery in tracheobronchial ruptures. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 20(2):399–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00798-9

Chu X, Chen W, Wang Y, Zhu L, Zhang M, Zhang S (2022) ECMO for paediatric cardiac arrest caused by bronchial rupture and severe lung injury: a case report about life-threatening rescue at an adult ECMO centre. J Cardiothorac Surg 17(1):142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-022-01856-0

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Ayperi Öztürk and Bedrettin Yıldızeli, from whose experience I benefited from the management of the case.

Funding

The study received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EA wrote the initial draft of manuscript. EA, OA, FK, MYH, HO, and HK managed the diagnosis and treatment. EA, OA, FK, MYH, HO, and HK approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written and verbal informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Afsin, E., Koşcu, Ö., Küçük, F. et al. A rare and late complication of lung cancer: bronchial rupture. Egypt J Bronchol 18, 26 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43168-024-00279-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43168-024-00279-w