Abstract

Background

With the vision of healthy aging, the Egyptian Academy of Bone and Muscle Health followed an established guideline development process to create the Egyptian 24-h movement clinical guideline for adults aged 50 years and older adults. This guideline highlights the significance of movement behaviors across the whole 24-h day. Online databases (PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library) were searched for relevant peer-reviewed studies that met the a priori inclusion criteria.

Results

A total of 53 studies met the inclusion criteria. Leveraging evidence from the review of the literature led to the development of 27 statements answering the 5 key questions. Results revealed a major change in the previous basic understandings as it shifts away from focussing on a sole movement behavior to the combination of all the movement behaviors. Based on this, the final guideline was developed providing evidence-based recommendations for a “Healthy 24-Hour Day”, comprising a mix of light-intensity and moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity, sleep, and sedentary behavior.

Conclusion

The developed guidelines are meant to help in the decision-making process and are intended for use by adults and older both nationally and internationally; also, for endorsement by the policy-makers. Dissemination and implementation efforts would impact positively on both health professionals and researchers and would also be useful to interested members of the public sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lack of physical activity has been linked to poor health and the development of various chronic illnesses with consequent potential disability in later life [1]. Despite these findings, it has been reported that nearly a quarter of people aged 50 years and older do less than 30 min of physical activity a week [2]. Musculoskeletal-wise, physical inactivity has a negative impact on both bone and muscle strength, reaction time, as well as endurance and posture. Concerning body organs, low level of physical activity is a well-known predisposing factor for several comorbidities including obesity, type II diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, and cancer particularly colon and breast cancer leading to premature death or disability [3]. At the supernational level, the World Health Organization (WHO) had estimated a yearly rate of two million premature deaths due to physical inactivity [4]. Although most of this data are from younger populations, other studies reported that this problem applies to older populations as well [2].

In the next Egyptian demographic transition, the number of elderly persons aged 60 + is expected to be more than twice as high between 2020 and 2050 from 8.4 million (8% of the total population) to 22 million (14%) [5]. In concordance with the industrial countries, a lack of physical activity has also been reported amongst Egyptian older adults. Earlier data revealed that less than 10% of the Egyptian population practice regular exercises, of them, the most inactive population were those over the age of 60 years old [6, 7]. The WHO report about physical activity in Egypt revealed that the prevalence of physical inactivity in Egyptian females over 70 years old was 55% whereas in men of the same age group was 35% [8]. Ageing is an evitable stage of life; therefore, it is important to have guidelines for physical activity which so far are not available in Egypt. With the vision of healthy aging, this work was carried out aiming to develop the Egyptian 24-h movement guidelines for adults aged 50 years and older with consideration of a balanced approach to sleep, sedentary behavior, and physical activity. These guidelines emphasize the significance of movement behaviors across the whole 24-h day.

Methodology

Study design

The framework used to develop the guidelines is consistent with the “Clinical, Evidence-based, Guidelines” (CEG) initiative protocol [9]. The methodology was designed to minimize bias, maximize transparency, and ensure high quality of the systematic reviews. The evidence-based component of the manuscript accommodated the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis guidelines for reporting systematic reviews [10]. The project was an initiative led by the Egyptian Academy of Bone and Muscle Health.

Ethical aspects

This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. This was a multistep process that followed the “Clinical, Evidence-based, Guidelines” (CEG) initiative protocol, ethical approval code: 34842/8/21, ethical board Tanta University.

Core team

The core team provided an overview of the guideline development process, responsibilities, and timelines. The core team also drafted a set of research questions for each of the three behaviors: sleep, sedentary, and physical activity, as well as the integration of all these behaviors. The core team reached an agreement on the target Population, Intervention, Comparator and Outcomes (PICO) [11] (Table 1).

Literature review team

The evidence reviews were conducted by 2 experienced researchers and an expert in methodology. This depended on the identified research questions. The team addressed the gaps and generated the info for every behavior [12]. The articles search was carried out for the period from January 2000 till January 2024. The search keywords were identified based on different combinations of the PICO elements. Literature searches were carried out on 18th December 2023 for PubMed and Cochrane Library databases, and on 29th December 2023 for Embase. Duplicate screening of literature search results was carried out electronically. Further studies of relevance to the review were identified by an update of the review of the literature and from the lists of references of studies retrieved in the former initial database search. Recommendations regarding each section were provided by each of the experts in charge of the review of the literature, based on the evidence, when this was available, or on their own experience. The workgroup used the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine (OCEBM) system [13] to determine the level of evidence for each section.

Inclusion criteria

To be included in the current review, studies were required to meet the following criteria: (1) the study was published in an English-language, refereed journal with full-text availability; (2) the study contained original research (clinical guidelines, systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), uncontrolled trials, observational studies including cohort, case–control and cross-sectional studies); (3) the study included one or more assessment of each 24-h movement behavior, that is, physical activity, sedentary behavior and sleep; (4) to have a clearly described methodology including the PICO elements of the reviewed question.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Editorials, commentaries, conference abstracts, and non-evidence-based narrative/personal reviews were excluded; 2. Studies or clinical guidelines that referred only to admitted or hospitalized populations; 3. Studies or clinical guidelines that included populations other than adults or older adults.

Results

Review of the literature

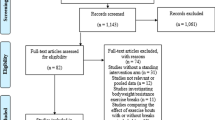

The database systematic literature search yielded a total of 4987 relevant potential publications. Figure 1 shows the flowchart summarising the study selection process. After removing duplicates, 3813 records remained. After screening the titles and abstracts, 99 potentially relevant citations were obtained for full-text review. Of those, after completing the reading 51 studies met the inclusion criteria. Two additional citations relevant to this work were identified following an up-to-date search and those retrieved from the bibliography of the included articles. Therefore, a total of 53 studies published met the eligibility criteria and consequently were included in this work. These included nine clinical guidelines: WHO [14] (World Health Organization, 2010), USA [15] (Department of Health and Human Services, 2018), Canada [16] (Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, 2011), Germany [17], United Kingdom–UK [18] (Department of Health, Physical Activity, Health Improvement and Protection, 2011), Australia [19], the Netherlands [20], New Zealand (Ministry of Health, 2013) [21] and India [22].

Targeted population and guidelines development process

The targeted population included adults aged 50 years and older. The Egyptian Academy of Bone and Muscle Health was the organizing body. The professionals involved were experts in rehabilitation medicine, physical activity and health promotion, epidemiology, guidelines development, psychology as well as fall prevention. Consensus was achieved following multiple online meetings followed by online comprehensive feedback.

Results of the systematic review

The exercise prescription

This guideline provides evidence-based public health physical activity programs constructed in a systematic and individualized style in terms of frequency, intensity, time, type, volume, and progression that offer significant health benefits and mitigate health risks. This has been identified as the FITT-VP formula or principle. The FITT is a good approach to monitor the individual person’s exercise program and progression. The parameters of the exercise prescription are shown in Table 2.

Baseline assessment and goal setting

The initial step to implement changes in the subject’s physical activity is best predicted by evaluating the person’s baseline activities and readiness to change. This should be carried out using an evidence-informed model with the goal of identifying: (1) the current level of exercise, (2) the presence or absence of asymptomatic/symptomatic known disease, and (3) desired intensity of exercise. Subsequently, the healthcare professional should educate the individual about the benefits of physical activity, changing some of the current behaviors, and motivate him/her with relevant personal goals, such as improving physical function or strength, balance, preventing falls, management of weight, improving chronic disease management, and preventing falls. Consequently, the individual should be able to agree with the healthcare professional on an initial set of achievable goals. Table 3 shows the developed Arabic Sedentary, Activity, Sleep Assessment (SASA) questionnaire, and associated explanatory figures for the assessment and monitoring of the exercise level of the individual subject (Supplement 1 shows the English copy of the SASA questionnaire).

Statements

Guided by the key questions, the systematic review was carried out to identify the effects of the 4 behaviors on the identified health outcomes. These are summarized in Table 4.

The Egyptian 24-h movement guidelines

Considering the overall health benefits, adults aged 50 years and older should be physically active every day, ensure sufficient sleep, and minimize sedentary behavior. Greater health benefits can be achieved by replacing sedentary behavior with extra physical activity and trading light physical activity for more moderate to vigorous physical activity, whilst continuing to have adequate sleep.

Overarching principles

-

All persons 50 years and above should keep moving/physically active as much and as frequently as possible. They should practice physical exercises on a regular basis at least 5 days a week.

-

Exercise programs should be customized to the individual’s needs. No common exercise program can fit all.

-

Individual’s medical and physical status are considerable factors in choosing the parameters of the adopted exercise program.

-

The heavier the exercise level, the greater the benefit. However, light-moderate physical activity is better than nothing.

-

Benefits of physical activity included a reduced risk of falling and the potential to develop a fracture; also reduced risk of several chronic health conditions, provides longer healthy life span, improved quality of life, and reduced overall mortality rate.

-

Sedentary behavior in the elderly is the biggest opponent of healthy aging.

-

Whenever appropriate, daily physical activity is advised.

-

Baseline assessments for functional ability, quality of life, sarcopenia, and falls risk are important and should be carried out for every older adult.

-

The physical activity programs are dynamic and progressive in nature, including exercises with a progressive intensity focusing on daily mobility routine with a flexible frequency.

-

Gradual increase in physical activity is the safest method for minimizing the risk of injury. The optimum approach is to start with moderate-intensity activities, with a progressive increase first in terms of activity duration, then in frequency, and finally in intensity. This would lead to increased benefits with a low incidence of side effects.

-

Physically inactive people but otherwise healthy and asymptomatic may start with light- to moderate-intensity exercise. In the absence of symptoms, they should progress gradually as advised by the exercise prescription guidelines.

-

Progression of physical activity over time is not only important for more health benefits but also for motivation and adherence.

-

Active older adults may engage in physical activities beyond the identified thresholds.

-

Consulting an experienced healthcare professional/practitioner is advisable before increasing the physical load is recommended for healthy older adults.

-

Multicomponent physical activities integrating many types of exercises (strengthening, endurance, and balance exercises) are advised.

-

Injuries and adverse effects during all forms of physical activity are negligible, however appropriate safety practices must be ensured.

-

Structured and group-based intervention/rehabilitation is advised for improving motivation, reducing cost, understaffing, and improving long-term adherence.

-

The guidelines and physical activities advised should be promoted at several levels individual, family, community, caregivers, technology, and policymakers.

-

No current recommendations support the use of personal devices such as wearables

Guidelines

To achieve a healthy 24-h, adults aged 50 years or older should:

General elderly population

-

1.

Physical activity

-

1.1 Aerobic training:

-

Thirty to 60 min a day of moderate-intensity aerobic activity at least 5 days/week; or

-

Fifteen to 30 min a day of high-intensity aerobic activity at least 5 days/week; or

-

an equivalent mix of moderate- and high-intensity aerobic workouts all around the week.

-

-

1.2 Resistance training:

-

Non-consecutive 2 to 3 days a week of resistance training should be recommended.

-

Each exercise should include 2–3 sets of resistance exercises working on multi-joint exercises per major muscle group and of intensity equal to 70–85% of 1 repetition maximum (1RM).

-

Performing the muscle strengthening exercises in the positions and forms of real-life daily activity movements is prescribed as functional strengthening exercises. This type of exercise is recommended as well as regular strengthening exercises.

-

-

1.3 Balance training:

-

Practicing of 30 min balance endurance exercises 2–3 times a week is recommended.

-

Combined static and dynamic balance training should be practices

-

-

-

2.

Sedentary behavior:

All adults including older adults are advised to decrease their sedentary time and push their bodies to move as frequently as possible; therefore, the individual should:

-

Limit the amount of time spent being seated.

-

Replace inactive time with any kind of physical activity of any intensity (including light intensity)

-

-

3.

Sleep:

-

Ensure appropriate sleep duration (7–9 h) and sleep consistency (good-quality sleep, with going to bed and getting up at the same time)

-

-

4.

Integrated behavior:

All adults and older adults are advised to practice regular frequent multicomponent physical training exercise that involves a combination of aerobic, strengthening, and balance exercises in different levels of intensity. This is besides decreasing the inactive time and ensuring good sleep quality.

Elderly people with special conditions

-

1.

People with chronic conditions

Among older adults, chronic comorbidities and illnesses such as cancer, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular, hyperlipidemia, and arthritis are the leading causes of death and/or disability among older adults [35]. There is no direct evidence of specific sedentary behavior for these subpopulations. Hence, the evidence for sedentary behavior recommendations for general populations remains applicable to them [14]. On the other hand, special precautions should be considered when offering an exercise prescription for those patients with chronic conditions. Table 5 shows the suggested exercise prescription modifications and special considerations and physical activity recommendations for patients with specific medical conditions.

-

2.

Patients at high risk of fragility fracture

-

Strict caution should be practiced when prescribing moderate (e.g., running, racquet sports, skipping) or high (e.g., drop or high vertical jumps) impact exercise for these patients.

-

Safety or efficacy is questionable in individuals with a history of fractured vertebrae or Major osteoporotic fracture FRAX score of 15% calculated by the Egyptian FRAX.

-

The most dangerous movements especially for those with vertebral fracture are those that entail flexion and twisting of the spine or rapid, repetitive, sustained, weighted, or end range of motion

-

-

3.

Frail adults/older adults

-

Multicomponent exercise program including progressive resistance training works well for frailty fighting.

-

Before prescribing the exercise dose, measuring aerobic fitness by cardiopulmonary exercise testing is recommended to determine exercise tolerance.

-

Progression or regression of exercise intensity is dependent on the person’s tolerance and general condition is recommended according to the person’s tolerance and health condition.

-

Resistance training has better results if accompanied by the intake of the proper amount of protein.

-

Specific structured exercise programs such as modified tai chi or certain types of yoga could prevent injury from falls.

-

Supervised, group-based exercising protocols are advised as they may enhance motivation and adherence

-

Homed-based and even bedside exercises are possible options to promote physical activity in very frail old adults.

-

Table 6 shows a summary, with examples of the Egyptian “Healthy 24-Hour” movement guideline.

Discussion

Preceded only by tobacco use, hypertension, and high blood glucose levels, physical inactivity was categorized as the fourth leading risk factor for noncommunicable diseases [36, 37], triggering about 41 million deaths annually (correspondent to 74% of all deaths globally) [38]. New research studies recommend that the structure of movement behaviors within a 24-h period may have a strong effect on health across the lifespan. Consistent with this paradigm of integrated movement behavior, the WHO as well as several countries across the world have developed “24-h movement guidelines” for different age groups. The purpose of this work was to develop “the Egyptian 24-h movement guidelines” for adults 50 years and older. This document is proposed for use by policymakers, health professionals, researchers, and interested individuals. Figure 2 shows the logo of the proposed national campaign. This 24-h movement guideline is relevant to all Egyptians aged 50 years or older, irrespective of gender, socio-economic status, or cultural background. The guideline development process adhered to the “Clinical, Evidence-based, Guideline” framework used to develop previous national guidelines in Egypt [9].

The principal concept of the developed 24-h movement guideline is that the structure of all movement behaviors throughout the day is strongly correlated to the individual’s health, and delivers exclusive, evidence-based opportunities to participate in movement behavior integrations that meet the individual’s requirements and personal preferences. This comes in agreement with the previously published 24-h guidelines published by the WHO and 8 other health authorities worldwide [14, 15, 17,18,19,20,21,22]. This paradigm represents a major change in the previous basic understandings, as it shifts away from focussing on a sole movement behavior to the combination of all the movement behaviors. In turn, this endorses the growing body of evidence advocating that the mix of movement behaviors over a 24-h day impacts a wide range of health outcomes [39,40,41,42].

The disengagement from any form of physical activity is not only prevalent in Egypt. In fact, it is an international challenge. Whilst 35% of older adult men and 55% of women have been reported as physically inactive, more than 40% of the adult European population do not engage in any form of physical activity, and only 8% regularly exercise [43]. Sedentary behavior and physical inactivity are directly linked to increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease [44], obesity, diabetes [45], and autoimmune rheumatic diseases [46]. WHO data [8] indicate that 86% of deaths in Egypt are due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) mortality, with cardiovascular disease followed by cancer being the main causes on top of the list. This highlights the importance of having a national 24-h movement guideline in Egypt, particularly, increasing levels of physical activity have been reported as a catalyst in the reduction of the above consequences.

In concordance with the earlier published guidelines [5, 29], the developed Egyptian 24-h movement guideline, revealed similar physical activity components for both adults and older adult age groups. Demographic data from Egypt reveal that life expectancy at birth for men is 68.5 years whereas for women it is 73.2 years. Results of a recent study in Egypt revealed that patients aged 50 years and older are at higher risk of falling and sustaining a fragility fracture [47]. This was the reason for including Egyptian adults aged 50 years and older in this guideline. However, this guideline may not be appropriate for adults aged 50 years or older living with a disability or a medical condition; these individuals should seek advice from their treating health professional for guidance. The guidelines are meant to help in the decision-making process but do not clarify all uncertainties of patient care. Although adopting this guideline can be challenging at times; progressing towards any of the targets identified in this guideline will result in some health benefits.

These guidelines stated that enhancing physical activities among adults and older adults should be promoted at different levels. This can be at the individual level, based on instinct-individual motivation; or community-based (families, friends, caregivers, policy-makers), or health professionals (individually or in small groups in generic or tailored exercise regimen) to technology (devices that assess activity, e-health or m-health solutions, mixed reality platform for increasing motivation). A logo (Fig. 2) has been developed by the Egyptian Academy of Bone and Muscle Health to spread the word and enhance the involvement of Egyptian adults and older adults at a national level. Evidence-based strategies could enhance adherence and monitoring could facilitate success.

In conclusion, there is a large body of evidence for the benefits of physical activities for healthy aging, and this is expressed in the development of several guidelines for different health conditions that stress the importance of incorporating physical activities for adults and older adults. This is endorsed by the fact that promoting physical activity, particularly in older adults could be more beneficial as health gains could come faster than in other age groups. physical inactivity results in limitations in body functioning and mobility and reduces the opportunity for independent living in later life. Physical activity in both adults and older adults, regardless of chronic disease, was reported to be associated with delayed physical disability and the maintenance of independent living. The developed Egyptian 24-h movement guideline endorses the recommendations for physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep which should be combined into a single public health domain that incorporates movement across the full 24-h day. A national campaign should be launched under the title “Moving more make your life matter”.

Availability of data and materials

Available upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMD:

-

Bone mineral density

- FRAX:

-

Fracture Risk Assessment

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- PICO:

-

Population, Intervention, Comparator and Outcomes

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Janssen I (2012) Health care costs of physical inactivity in Canadian adults. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 37:803–806. https://doi.org/10.1139/h2012-061

Warburton DE, Nicol C, Bredin SS (2006) Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Can Med Assoc J 174:801–809. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.051351

Gill TM, Williams CS, Tinetti ME (1995) Assessing risk for the onset of functional dependence among older adults: the role of physical performance. J Am Geriatr Soc 43:603–609

Luo L, Cao Y, Hu Y, Wen S, Tang K, Ding L, Song N (2022) The associations between meeting 24-Hour Movement Guidelines (24-HMG) and self-rated physical and mental health in older adults-cross sectional evidence from China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(20):13407. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013407

The rights and wellbeing of older persons in Egypt. https://arabstates.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/country_profile_-_egypt_27-10-2021_0.pdf Accessed on 7 Mar 2024

El Miedany Y, Mahran S, Elwakil W (2023) One musculoskeletal health: towards optimizing musculoskeletal health in Egypt—how to be a bone and muscle builder by the Egyptian Academy of Bone Health and Metabolic Bone Diseases. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil 50:33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43166-023-00199-5

Abdelkawy K, Elbarbry F, El-Masry SM, Zakaria AY, Rodríguez-Pérez C, El-Khodary NM (2023) Changes in dietary habits during Covid-19 lockdown in Egypt: the Egyptian COVIDiet study. BMC Public Health 23(1):956. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15777-7

WHO report on physical activity profile in Egypt (2022) https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/country-profiles/physical-activity/physical-activity-egy-2022-country-profile.pdf?sfvrsn=50db9547_5&download=true. Accessed on 7 Mar 2024

El Miedany Y, Abu-Zaid MH, El Gaafary M et al (2022) Egyptian guidelines for the treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis — 2022 update. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil 49:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43166-022-00153-x

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 151:W65–94

Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P (2007) Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2007(7):16

Leclercq E, Leeflang MM, van Dalen EC, Kremer LC (2013) Validation of search filters for identifying pediatric studies. J Pediatr 162:629–634

OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group (2011) The Oxford levels of evidence 2. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Oxford, UK

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S et al (2020) World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med 54:1451–1462

Physical Activity (2018) Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf. Accessed 30 April 2024

Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (2011) Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines and Canadian Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines. http://www.csep.ca/en/guidelines/read-the-guidelines

Rütten A & Pfeifer K (2016) National Recommendations for Physical Activity and Physical Activity Promotion FAU University Press. https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-fau/home

Department of Health, Physical Activity, Health Improvement and Protection Start Active, Stay Active:A report on physical activity from the four home countries'Chief Medical Officers. London: Department of Health, Physical Activity, Health Improvement and Protection; 2011. https://www.sportengland.org/media/2928/dh_128210.pdf

Brown WJ, Moorhead GE, Marshall AL (2005) Choose Health:Be Active:a physical activity guide for older Australians. Commonwealth of Australia and the Repatriation Commission, Canberra

Weggemans RM, Backx FJG, Borghouts L, Chinapaw M, Hopman MTE, Koster A et al (2018) Committee Dutch Physical Activity Guidelines 2017. The 2017 Dutch Physical Activity Guidelines. Int J BehavNutr Phys Act 15(1):58

Ministry of Health Guidelines on Physical Activity for Older People (aged 65 years and over) Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2013. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/guidelines-physical-activity-older-people-aged-65-years-and-over.

Misra A, Nigam P, Hills AP, Chadha DS, Sharma V, Deepak KK et al (2012) Physical Activity Consensus Group. Consensus physical activity guidelines for Asian Indians. Diabetes TechnolTher 14(1):83–98

Muñoz-Martínez FA, Rubio-Arias J, Ramos-Campo DJ, Alcaraz PE (2017) Effectiveness of Resistance circuit-based training for maximum oxygen uptake and upper-body one-repetition maximum improvements: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 47(12):2553–2568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0773-4

Lai C-C, Tu Y-K, Wang T-G, Huang Y-T, Chien K-L (2018) Effects of resistance training, endurance training and whole-body vibration on lean body mass, muscle strength and physical performance in older people: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Age Ageing 47(3):367–373. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy009

El-Kotob, R., Ponzano, M., Chaput, J.-P., Janssen, I., Kho, M.E., Poitras, V.J., et al. (2020) Resistance training and health in adults: an overview of systematic reviews. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 45(10 Suppl. 2): this issue. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0245

Saeidifard F, Medina-Inojosa JR, West CP, Olson TP, Somers VK, Bonikowske AR et al (2019) The association of resistance training with mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 26(15):1647–1665. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319850718

Liu CJ, Latham N (2010) Adverse events reported in progressive resistance strength training trials in older adults: 2 sides of a coin. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 91(9):1471–1473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.001

Ross R, Chaput JP, Giangregorio LM, Janssen I, Saunders TJ, Kho ME, Poitras VJ, Tomasone JR, El-Kotob R, McLaughlin EC, Duggan M, Carrier J, Carson V, Chastin SF, Latimer-Cheung AE, Chulak-Bozzer T, Faulkner G, Flood SM, Gazendam MK, Healy GN, Katzmarzyk PT, Kennedy W, Lane KN, Lorbergs A, Maclaren K, Marr S, Powell KE, Rhodes RE, Ross-White A, Welsh F, Willumsen J, Tremblay MS (2020) Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Adults aged 18–64 years and Adults aged 65 years or older: an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 45(10 (Suppl. 2):S57-S102. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0467

Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, Tiedemann A, Michaleff ZA, Howard K et al (2019) New Cochrane review assesses the benefits and harms of exercise for preventing fall s in older people living in the community. Saudi Med J 40(2):204–205

Saunders TJ, McIsaac T, Douillette K, Gaulton N, Hunter S, Rhodes R et al (2020) Sedentary behaviour and health in adults: an overview of systematic reviews. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0272

2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee (2018) 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report, Washington, DC, USA. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/PAG_Advisory_Committee_Report.pdf Accessed on 8 Mar 2024

Chaput JP, Dutil C, Featherstone R, Ross R, Giangregorio LM, Saunders TJ et al. (2020) Sleep duration and health in adults: an overview of systematic reviews. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab 45(10 Suppl. 2). https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0034

Chaput J-P, Dutil C, Featherstone R, Ross R, Giangregorio LM, Saunders TJ et al (2020) Sleep timing, sleep consistency, and health in adults: a systematic review. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0032

Janssen I, Clarke AE, Carson V, Chaput JP, Giangregorio LM, Kho ME, et al. (2020) A systematic review of compositional data analysis studies examining associations between sleep, sedentary behaviour, and physical activity with health outcomes in adults. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab 45(10 Suppl. 2): https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0160

Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Arias E (2014) Mortality in the United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief 178:1–8

Lee I-M, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT (2012) Effect of physical inactivity on major noncommunicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 380(9838):219–229

WHO. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases (2014) World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564854. Accessed 9 Mar 2024

World Health Organization (2009) Global health risks : mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44203. Accessed 9 March 2024

WHO. Physical activity. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity Accessed on 9 Mar 2024

Chastin SFM, Palarea-Albaladejo J, Dontje ML, Skelton DA (2015) Combined effects of time spent in physical activity, sedentary behaviors and sleep on obesity and cardio-metabolic health markers: a novel compositional data analysis approach. PLoS One 10(10):e0139984

McGregor DE, Carson V, Palarea-Albaladejo J, Dall PM, Tremblay MS, Chastin SFM (2018) Compositional analysis of the associations between 24-h movement behaviours and health indicators among adults and older adults from the Canadian health measure survey. Int J Environ Res Publ Health 15(8):1779

Nikitas C, Kikidis D, Bibas A, Pavlou M, Zachou Z, Bamiou DE (2022) Recommendations for physical activity in the elderly population: a scoping review of guidelines. J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls 7(1):18–28. https://doi.org/10.22540/JFSF-07-018

(2014) European Commmision Eurobarometer on Sport and Physical Activity. Brussels. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-14-207_el.htm

Warren TY, Barry V, Hooker SP, Sui X, Church TS, Blair SN (2010) Sedentary behaviors increase risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42:879–885

Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE (2003) Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA 289:1785–1791

Pinto AJ, Roschel H, de SáPinto AL, Lima FR, Pereira RMR, Silva CA et al (2017) Physical inactivity and sedentary behavior: Overlooked risk factors inautoimmune rheumatic diseases? Autoimmun Rev 16(7):667–674

El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Gadallah N, Mahran S, Fathi N, Abu-Zaid MH, Tabra SAA, Shalaby RH, Abdelrafea B, Hassan W, Farouk O, Nafady M, Ibrahim SIM, Ali MA, Elwakil W (2023) Incidence and geographic characteristics of the population with osteoporotic hip fracture in Egypt- by the Egyptian Academy of Bone Health. Arch Osteoporos 18(1):115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-023-01325-8. Erratum.In:ArchOsteoporos.2024;19(1):14

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

All authors declare that they did not receive any kind of funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Clinical, Evidence-based, Guidelines (CEG) initiative protocol was approved by the local ethical committee. Ethical approval code: 34842/8/21, ethical board Tanta University.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Prof. Safaa Mahran and Yasser El Miedany are from the editorial board of the journal. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

43166_2024_259_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Supplement 1. Self-reported sedentary, physical activity and sleep quality assessment questionnaire for the evaluation and monitoring of the exercise level of the individual person.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El Miedany, Y., Toth, M., Plummer, S. et al. The development of the Egyptian 24-h movement guidelines for adults aged 50 years and older: an integration of sleep, sedentary behavior, and physical activity by the Egyptian Academy of Bone and Muscle Health. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil 51, 31 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43166-024-00259-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43166-024-00259-4