Abstract

Background

Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis constitutes 1% of the head and neck manifestation of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis. The rarity of the disease along with its non-specific presentation may pose a challenge in diagnosis.

Case presentation

We present a case of a 33-year-old patient who presented with a gradual onset of unilateral hearing loss. Endoscopic examination revealed leukoplakic lesions over the bilateral torus tubarius with audiological assessment revealing a mixed hearing loss in the left ear. Patient completed a 6-month course of anti-tuberculous therapy with a complete resolution of nasopharyngeal lesions and hearing loss.

Conclusion

We hypothesize that tuberculosis of the nasopharynx may not only lead to impaired middle ear ventilation but also damage to the ossicular chain and inner ear structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) has shown a steady increase over recent years, constituting 17% of all newly notified tuberculosis infection in 2021 [1]. Ten to 35% of EPTB have been found to manifest in the head and neck region, affecting its numerous structures such as the pharynx, larynx, salivary glands, and lymph nodes [2]. Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis is a rare manifestation of head and neck tuberculosis, consisting of only 1% of all reported EPTB in the region [3]. Due to its rarity, its mimicry of neoplastic diseases of the head and neck, and the non-specific symptoms of its presentation, diagnosis of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis may be challenging [3, 4]. We present a case of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis presenting with unilateral hearing loss. Complete resolution of symptoms was achieved upon completion of anti-tuberculous therapy.

Case presentation

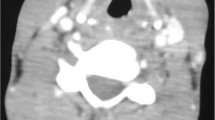

A 33-year-old female patient of Malay ethnicity was referred to the otorhinolaryngology clinic for a 2-week history of left-sided gradual hearing loss associated with tinnitus. She denied any nasal symptoms or trauma to the ear. There were no infective symptoms, and she denied any neck swelling or constitutional symptoms. Examination of the left ear revealed a retracted tympanic membrane with the presence of an air-fluid level. Nasal endoscopic examination revealed leukoplakic lesions at the bilateral torus tubarius, more predominant on the left side (Fig. 1). There was also the presence of thick mucoid secretions in the bilateral nasal cavities.

Biopsy was done on the bilateral torus tubarius. Histopathological examination revealed no granuloma or evidence of dysplasia. The tissue samples were positive for both mycobacterial culture and mycobacterium DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) studies. In view of the patient’s complaints of hearing loss, a baseline pure tone audiometry (PTA) was done upon presentation to our clinic which showed left-sided mixed hearing loss with a normal hearing threshold of the right ear (Fig. 2a). Patient was started on rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide regime, and treatment were successfully completed after 6 months. Subsequent follow-up in our clinic showed complete resolution of nasopharyngeal lesions (Fig. 3) with normalization of left-sided hearing loss (Fig. 2b).

Discussion

Despite being one of the most uncommon manifestations of EPTB, nasopharyngeal tuberculosis (NPTB) has been recently reported more frequently in the literature. The first reported review of NPTB was in the 1980s, which described the disease as under-diagnosed due to its non-specific presentation [5]. A more recent review showed that head and neck tuberculosis rarely manifests with generalized constitutional symptoms. Instead, the symptoms may occur based on the site of tuberculous infection [6]. The commonest symptom of NPTB has been reported as cervical lymphadenopathy followed by nasal symptoms such as rhinorrhoea and nasal congestion [7]. In this case report, the patient presented solely with hearing loss with an absence of neck or nasal symptoms.

The clinical features of NPTB may have a high degree of mimicry with other inflammatory and neoplastic diseases of the nasopharynx. In a review of 23 patients with NPTB, 30% of the patients showed normal nasopharynx appearance with 39% showing a mass of the nasopharynx followed by 21.7% showing irregular mucosal appearance [8]. Due to its non-specific features, diagnosis of NPTB may only be achieved by biopsy of the suspected site with samples being sent for histopathological examination and mycobacterium studies such as Ziehl–Neelsen staining, mycobacterium culture, and mycobacterium DNA PCR [9].

Due to its intricate relationship with the middle ear via the Eustachian tube, several cases have been reported elucidating the otological sequelae of NPTB. Dysfunction of the Eustachian tube has been reported to cause otitis media with effusion leading to symptoms of ear fullness, hearing loss, and tinnitus [10, 11]. NPTB has also been reported to cause chronic otitis media with concomitant otomastoiditis [12]. These cases only reported the symptom of hearing loss without exploring the degree and type of hearing loss occurring in patients with NPTB.

Structural damage to the nasopharynx and Eustachian tube specifically may lead to significant dysfunction causing impaired ventilation of the middle ear. As a result, fluid accumulation in the middle ear will lead to conductive hearing loss and sensation of fullness. Resolution of fluid accumulation will subsequently improve conductive hearing loss. These are consistent with the recovery of hearing loss in the patient reported here and previously reported cases [10, 11].

On top of the conductive hearing loss, our patient also showed a mild sensorineural hearing loss of 30–40 dB HL at the 3000–4000-Hz frequency level with a notch at the 2000-Hz frequency. Upon completion of the tuberculous treatment, the sensorineural hearing level subsequently recovered with complete normalization of the hearing threshold. There have been several reports of sensorineural hearing loss manifesting as a complication of tuberculosis. In a retrospective review of seven aural and central nervous system (CNS) tuberculosis cases, it was found that 85.7% of the patients had sensorineural hearing loss upon diagnosis of TB [13]. Miliary tuberculosis has also been previously reported to cause sensorineural hearing loss via the presence of small tuberculoma within the inner ear structures [14]. With respect to the pattern of hearing loss, a notch at the 2000-Hz frequency may be hypothesized as a presence of ossicular chain damage possibly secondary to granulomatous inflammation due to the tuberculous infection. Due to the prompt diagnosis and treatment with an anti-tuberculous regime, the hearing threshold of the frequency improved to 20 dB, indicating resolution of the inflammation or damage to the ossicular chain.

Conclusion

This case report presents a unique audiological perspective of NPTB showing both conductive and sensorineural hearing loss as consequences of the disease. Early diagnosis and intervention ensured patient’s recovery of nasal and audiological symptoms. Complete nasal and otologic examinations on top of early biopsy for mycobacterium studies are essential in ensuring correct diagnosis is achieved. Hearing assessment plays an essential role in monitoring any otological or audiological sequelae of NPTB. We propose that a baseline hearing assessment be performed in all patients with tuberculosis, especially affecting the structures of the head and neck. Further studies assessing the physiological and structural damages of tuberculosis to the middle and inner ear structures will be beneficial to elucidate the hearing loss outcome of NPTB.

Availability of data and materials

All data and material of this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- EPTB:

-

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PTA:

-

Pure tone audiometry

- NPTB:

-

Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis

References

World Health Organization (2022) Global tuberculosis report 2022. Geneva

Qian X, Albers AE, Nguyen DTM et al (2019) Head and neck tuberculosis: literature review and meta-analysis. Tuberculosis 116:S78–S88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tube.2019.04.014

Penjor D, Pradhan B (2022) Diagnostic dilemma in a patient with nasopharyngeal tuberculosis: a case report and literature review. SAGE Open Med Case Rep 10:2050313X221131389. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050313X221131389

Menon K, Bem C, Gouldesbrough D, Strachan DR (2007) A clinical review of 128 cases of head and neck tuberculosis presenting over a 10-year period in Bradford, UK. J Laryngol Otol 121:362–368. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215106002507

Waldron J, van Hasselt CA, Skinner DW, Arnold M (1992) Tuberculosis of the nasopharynx: clinicopathological features. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 17:57–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1365-2273.1992.TB00989.X

Pang P, Duan W, Liu S et al (2018) Clinical study of tuberculosis in the head and neck region—11 years’ experience and a review of the literature. Emerg Microbes Infect 7:4. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41426-017-0008-7

Darouassi Y, Aljalil A, Hanine A et al (2019) Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis: report of four cases and review of the literature. Pan Afr Med J 33:150. https://doi.org/10.11604/PAMJ.2019.33.150.15892

Srirompotong S, Yimtae K, Jintakanon D (2004) Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis: manifestations between 1991 and 2000. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 131:762–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.052

Min HJ, Kim CH (2017) Nasal or nasopharyngeal tuberculosis should be considered in the initial diagnosis of sino-nasal inflammatory diseases. Yonsei Med J 58:471–472. https://doi.org/10.3349/YMJ.2017.58.2.471

Hamzah MH, Mohamad I, Mutalib NSA (2021) Primary Eustachian tube tuberculosis. Medeni Med J 36:172–175. https://doi.org/10.5222/MMJ.2021.52460

Pankhania M, Elloy M, Conboy PJ (2012) Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis presenting with auditory symptoms. Case Reports 2012:bcr0120125475. https://doi.org/10.1136/BCR-01-2012-5475

Kim M, Lee JH, Lee HN et al (2022) Nasopharyngeal tuberculosis with concomitant middle ear tuberculosis: a case report and literature review. Ear Nose Throat J 2022:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/01455613221103087/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_01455613221103087-FIG4.JPEG

Diplan Rubio JM, Alarcón AV, Díaz MP et al (2015) Neuro-otologic manifestations of tuberculosis. “The great imitator.” Am J Otolaryngol 36:467–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AMJOTO.2015.01.018

Min SK, Shin JH, Mun SK (2018) Can a sudden sensorineural hearing loss occur due to miliary tuberculosis? J Audiol Otol 22:45–47. https://doi.org/10.7874/JAO.2017.00129

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledged that this is an original work except for the citation and quotation in which the sources have been clearly mentioned. There is no conflict of interest and no financial disclosures to report.

Funding

The writing of this manuscript was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MHZA and AZAH were all involved in the acquisition and interpretation of the data for this manuscript. MHZA performed the literature review and was responsible for the drafting and writing of the manuscript. Critical analysis and revision of the manuscript were done by AZAH. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the case subject.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zainal Abidin, M.H., Abdul Wahab, A.H. Unilateral hearing loss: case report on the insidious consequence of nasopharyngeal tuberculosis. Egypt J Otolaryngol 39, 64 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-023-00433-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-023-00433-z