Abstract

Background

Isolated histiocytosis of thyroid region is very rare; clinical history, exam, and radiological aspects are non-specific, and etiological reasoning is quite difficult considering the tremendous number of differential diagnoses.

Case presentation

This is the case of a 6-year-old girl who came to the emergency room with an acute presentation bulging of the anterior and left lateral regions of the neck. The palpation of the mass showed tenderness; there was no sign of inflammation, nor was there any fistula to the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

The patient was stable. She did not have any signs of compression. The initial blood showed anemia and inflammatory syndrome. She underwent cervical ultrasound exam that showed a mass at the expense of the left thyroid lobe; the mass extends through the sub-hyoid muscles to the lateral cervical region.

A CT scan with and without contrast injection was performed. It showed a heterogenous mass, which seemed centered in the anterior compartment, and from which it extended to the left lateral compartment, as well as the posterior compartment, invading the prevertebral muscles and englobing the carotid and the internal jugular vein.

The patient underwent surgical biopsy. A basal cervical incision was made, dissection with the myo-cutaneous plane. Per-operative observation established that the mass breeched the infrahyoid muscles, as well as the sternocleidomastoid muscle. A biopsy was performed without opening the middle line.

The pathological exam showed an eosinophilic granulomatosis, associated with Stembergoid cells. The immune-histochemical exam concluded that the lesion is histiocytosis. The patient underwent a cervicothoracic and pelvic CT scan to rule out systemic forms. The diagnosis of isolated histiocytosis of thyroid region was confirmed.

The patient underwent hemithyroidectomy, associated with careful dissection of extension of the mass to lateral compartment of the neck. Postoperative exam showed no abnormalities. No dysphonia and no hypocalcemia were observed.

The 8-month follow-up showed satisfactory results, no cervical swelling, and no signs of inflammation or compression. Postoperative naso-fibroscopy was normal.

Conclusions

The most important takeaway message of this work is that methodical approach of neck masses allows to rule out the most aggressive lesions frequently encountered, which allows clinicians to establish thorough diagnosis and management without further delay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Management of masses thattake place in both anterior and lateral cervical compartments is difficult, since understanding the anatomical content of the different compartments of the head and neck is essential to deduce diagnoses relative to localizations [1].

Case presentation

This is the extremely rare case of histiocytosis of thyroid gland of a 6-year-old girl, which was discovered in an acute episode first, which had an evolution of a lingering neck infection. However, the involvement of more than one cervical compartment at once, as well as the lesion’s aggressive aspect, increased diagnostic difficulty.

The palpation of the mass showed tenderness; there was no sign of inflammation, nor was there any fistula to the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Furthermore, the patient did not experience any pus discharge in her throat.

-

The patient was stable: no respiratory distress, no signs of sepsis, and no neurological abnormalities.

-

The patient did not have any signs of compression: no dysphagia and no dysphonia were depicted.

The initial blood test showed the following: hemoglobin of 8.1; with low VGM: 26; CRP: 160; hyperleukocytosis: 16,000, platelet count was normal; and urea and creatinine plasma levels were normal. There was no biological tumor lysis syndrome. TP was normal, and urea and creatinine count was normal. TSH and T4 were normal; calcium and albumin plasma levels were normal as well.

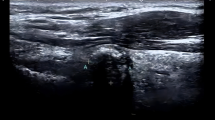

The patient underwent cervical ultrasound exam that showed a mass at the expense of the left thyroid lobe; the mass extends through the sub-hyoid muscles to the lateral cervical region (Fig. 1).

A CT scan with and without contrast injection was performed; it showed a heterogenous mass, which seemed centered in the anterior compartment, and from which it extended to the left lateral compartment, as well as the posterior compartment, invading the prevertebral muscles and englobing the carotid and the internal jugular vein (Fig. 2).

The patient underwent surgical biopsy; a basal cervical incision was made, dissection with the myo-cutaneous plane. Per-operative observation established that the mass breeched the infrahyoid muscles, as well as the sternocleidomastoid muscle. A biopsy was performed without opening the middle line (Fig. 3).

The pathological exam showed an eosinophilic granulomatosis, associated with Stembergoid cells. The immune-histochemical exam concluded that the lesion is histiocytosis.

The patient underwent a cervicothoracic and pelvic CT scan to rule out systemic forms.

The diagnosis of isolated histiocytosis of thyroid region was confirmed.

The patient underwent hemithyroidectomy, associated with careful dissection of extension of the mass to lateral compartment of the neck. Postoperative exam showed no abnormalities. No dysphonia and no hypocalcemia were observed.

The follow-up showed satisfactory results. The 8-month follow-up showed satisfactory results, no cervical swelling, and no signs of inflammation or compression. Postoperative naso-fibroscopy was normal.

The most important takeaway message of this work is that methodical approach of neck masses allows to rule out the most aggressive lesions frequently encountered, which allows clinicians to establish thorough diagnosis and management without further delay.

Discussion

Cervical masses in pediatric population can be the following: congenital, inflammatory, infectious, or neoplastic either benign or malignant [1]. The infectious etiology is generally either acute or chronic [1].

Lateral masses are most frequently infectious. Medical history yields very important data relative to diagnosis: the age of the patient, the duration, and history of head and neck infections.

The notion of tick-borne diseases is deduced according to residence location and travel to infested zones. Exposition to cats, their excrements, could unveil toxoplasmosis. Consumption of unpasteurized milk and a history of immune-compromised patients, tuberculosis [1].

Moreover, family history could be indicative of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 syndrome, neurofibromatosis, autoimmune diseases, vascular abnormalities, and head and neck cancers [1].

Cervical tumors are rarely malignant in children [2,3,4]. Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most frequently encountered [2,3,4,5] (Table 1).

Table 1 summarizes the most frequent malignant processes of the head and neck in children [2, 5].

Thyroglossal cysts are the most frequently encountered branchial arch malformations; the most frequent malformation of the head and neck in children is vascular malformations [1, 3, 4].

Cervical ultrasound, CT scan, and MRI play an important role in diagnosis orientations (Table 2) [3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) could help guide diagnostic reasoning; it is however overridden when radiological signs of aggressiveness are found [10]. Open biopsy and histological study are key to confirm diagnosis in lesions other than vascular malformations [10].

Histiocytosis of the head and neck represents 5–9 per 1 million patients [10]. It is mostly predominant in males, with a peak occurrence between 1 and 4 years of age [10].

Classifications of histiocytosis have changed in the last 50 years; historically, it was called histiocytosis X. It includes eosinophilic granuloma, Hand-Schuller-Christian disease, and Letterer-Siwe disease [9].

A new nomenclature classifies Langerhans cell histiocytosis in three categories: single-system single site (SS-s), single-system multiple site (Ss-m), and multiple site (MS) [9, 10].

Multiple site Langerhans histiocytosis may present in 2 forms: with or without organ involvement. Low-risk organs are lymph nodes, skin, bones, and pituitary gland; high risk organs are bone marrow, the liver, spleen, and the lungs [9].

Besides, a revised classification system of histiocytoses and neoplasms of macrophage dendritic cell lineages defines 5 groups regarding histological aspect and genetic profile (Table 3) [9, 10].

Single-system lesions occur in 65% of cases: 70–82% of bone lesions and 12% of skin lesions. In multisystem forms, the specific involvement of organs affects treatment priorities and prognosis [9].

Histological profile is based on electron microscopy or immunohistochemical reactivity of histiocytes to CD1a and/or S100. Electron microscopy shows characteristic Birbeck granules [10].

Thyroid histiocytosis is generally involved in systemic forms of histiocytosis. Isolated thyroid involvement is extremely rare [9, 10].

Isolated histiocytosis is managed by surgery: in this case, hemithyroidectomy or thyroidectomy. Association in some cases, with adjuvant therapies of chemoradiation, is discussed in multidisciplinary reunions [10].

Conclusions

This is the rare case of thyroid histiocytosis in children. The take-home message of this work is to discuss the differential diagnoses of aggressive masses that are located in the anterior and lateral cervical spaces, regarding frequency and severity, without delay to diagnosis and management.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Jackson DL (2018) Evaluation and management of pediatric neck masses: an otolaryngology perspective. Physician Assist Clin 3(2):245–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpha.2017.12.003

Chadha NK, Forte V (2009) Pediatric head and neck malignancies. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 17(6):471–476. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283323893 (PMID: 19745735)

Faingold R, Oudjhane K, Armstrong DC, Albuquerque PA (2002) Magnetic resonance imaging of congenital, inflammatory, and infectious soft-tissue lesions in children. Top Magn Reson Imaging 13:241–261

Navarro OM, Laffan EE, Ngan BY (2009) Pediatric soft-tissue tumors and pseudo-tumors: MR imaging features with pathologic correlation: part 1 Imaging approach, pseudotumors, vascular lesions, and adipocytic tumors. Radiographics 29(3):887–906. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.293085168 (PMID: 19448123)

Qaisi M, Eid I (2016) Pediatric head and neck malignancies. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 28(1):11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coms.2015.07.008

Rodriguez-Takeuchi SY, Renjifo ME, Medina FJ (2019) Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: pathophysiology and imaging findings. Radiographics 39(7):2023–2037. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2019190109 (PMID: 31697616)

Bansal AG, Oudsema R, Masseaux JA, Rosenberg HK (2018) US of pediatric superficial masses of the head and neck. Radiographics 38(4):1239–1263. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2018170165

Koeller KK, Alamo L, Adair CF, Smirniotopoulos JG (1999) Congenital cystic masses of the neck: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 19(1):121–46; quiz 152-2. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.19.1.g99ja06121 (Erratum. In: Radiographics 1999 Mar-Apr;19(2):282 PMID: 9925396)

Jezierska M, Stefanowicz J, Romanowicz G, Kosiak W, Lange M (2018) Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children - a disease with many faces Recent advances in pathogenesis, diagnostic examinations and treatment. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 35(1):6–17. https://doi.org/10.5114/pdia.2017.67095

Pandyaraj RA, Sathik Mohamed Masoodu K, Maniselvi S, Savitha S, Divya Devi H (2015) Langerhans cell histiocytosis of thyroid-a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Surg 77(Suppl 1):49–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-014-1118-2

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KC contributed in clinical management and investigation and analyzed and interpreted the patient data. MI contributed to clinical management of patient. OB operated on the patient and supervised the writing the article. All authors have read and agreed to its content. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of the patient’s clinical details and clinical images was obtained from the patient’s parent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Benhoummad, O., Cherrabi, K. & Imdary, M. Diagnosis difficulty of histiocytosis in the thyroid region of a child: a rare case report with literature review of differential diagnoses. Egypt J Otolaryngol 38, 147 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-022-00338-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-022-00338-3