Abstract

Background

Lipomas are the most common benign mesenchymal tumors. They are defined as subcutaneous neoplasms of mature adipocyte cells that can occur wherever fatty tissue is. Lipomas are rare in the upper aerodigestive tract. Usually asymptomatic, they may be painful, uncomfortable, or even life-threatening especially if voluminous and located in the upper aerodigestive tract.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old female patient has presented with dyspnea on mild effort and chronic orthopnea. The physical examination was normal while the fiber optic endoscopy revealed a submucosal round-shaped mass rising from the left side of the post-cricoid region. CT scan revealed a well-circumscribed fatty mass of the left piriform sinus for which the patient underwent an endoscopic transoral approach for a complete removal with good results.

Discussion and conclusion

Pharyngeal lipomas are rare entities that might be life-threatening. Although clinical manifestations are not specific, imaging techniques, especially MRI, help set the diagnosis showing a fatty mass of the upper aerodigestive tract. However, pathology examination is crucial to rule out low-grade liposarcomas. Surgical management is not well-codified and has benefited from the development of endoscopic techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lipomas are the most frequent mesenchymal benign tumors. They can develop in all fatty areas of the body, be solitary or multiple. They are primitive in the vast majority of cases and occur mainly in adults between 40 and 60 years of age [1]. Malignant transformation has never been described. Very rarely, in the head and neck region, they can be infiltrative [2, 3]. They do not regress spontaneously. Their prevalence is estimated at 0.6% of neoplasms [4, 5]. A scarcity is more marked in the ORL area, particularly the pharyngolaryngeal location.

We present the case of a pharyngeal lipoma involving the left piriform sinus diagnosed in a 67-year-old female patient presenting with mild exertional dyspnea and orthopnea, for which she underwent a complete endoscopic removal with a satisfactory clinical outcome.

Case presentation

A female patient in her sixties with no significant medical history was referred to the ENT outpatient clinic by her cardiologist for chronic orthopnea and dyspnea on mild physical effort associated with normal cardiac functioning. The patient reported a 05-year history of persistent pharyngeal foreign body sensation with recent snoring and sleep apnea. Otherwise, no other symptoms such as dysphagia, dysphonia, cough, or expectorations were described.

Physical examination disclosed no cervical lymphadenopathies and no goiter. Fiber optic endoscopy revealed a submucosal round-shaped mass rising from the left side of the post-cricoid region. The tumor was covered by normal mucosa and was moving up and down during swallowing and respiration. The mass filled the supraglottic region during inspiration and disappeared during swallowing (Videos 1 and 2).

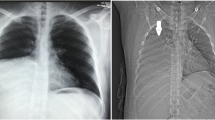

For further characterization of the tumor, a cervical CT scan with contrast injection was ordered. It showed a low-attenuation mass that rose from the left aryepiglottic fold (Figs. 1 and 2) with very thin septa, scattered small areas of soft tissue density, and thin capsule which made it hard to distinguish from the surrounding air in the upper aerodigestive tract.

The patient underwent an endoscopic transoral approach under general anesthesia for the complete removal of the tumor and the exceeding overlying pharyngeal mucosa. The tumor has a small peduncle with a narrow base originating from the post-cricoid area (Fig. 3). No sutures were placed in the root of the peduncle. The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient received antibiotics and paracetamol for 1 week and anti-reflux medication until complete healing of the wound. A feeding tube was used for 3 days; then, oral feeding was allowed; and the patient was discharged from the hospital. However, non-spicy mixed food was recommended for 2 weeks.

Histopathology examination (Fig. 4) confirmed the diagnosis of lipoma characterized by the presence of lobulated, mature adipocytes with minimal connective tissue stroma, enclosed in a thin, fibrous capsule with no cellular atypia.

The patient’s episodes of care timeline is reported in Fig. 5.

Discussion

Lipomas are the most common benign mesenchymal tumors [1]. They are usually presenting as subcutaneous neoplasms of mature adipocyte cells. However, they can occur wherever fatty tissue is found. In 80% of cases, they are typically subcutaneous lipomas with no particularities [1, 2]. Head and neck lipomas count for 13% of all cases, mainly located in the nuchal area [6]; less frequently in the anterior cervical region, infratemporal fossa, oral cavity, and parotid gland; and even more rarely in the upper aerodigestive tract [5]. In our case, the lipoma originated from the anterior wall of the left pyriform sinus.

Lipomas are usually described as painless, slow-growing soft tissue tumors of different sizes that are characterized by an insidious evolution. In fact, they usually remain silent and are often discovered fortuitously during a clinical examination or a radiology test. Nevertheless, lipomas of the upper aerodigestive tract may go unnoticed on CT scans due to the similarity of density between the air and the fatty portion especially in the pedunculated forms. They are most often sporadic in isolated cases. However, in 5–15% of patients, lipomas are multiple, thus described as lipomatosis, and approximately a third of these will be familial [7] as well as associated with other syndromes and diseases such as Gardner’s syndrome, Bannayan-Zonana syndrome, Dercum syndrome, Cowden syndrome, Proteus syndrome, and Madelung’s disease [8].

Clinically, lipomas may remain asymptomatic for a long period until reaching a considerate size; consequently, they are discovered at an advanced stage. On the other hand, for the symptomatic forms, and more precisely in the pharyngeal ones, clinical features depend on the location and the impact of these lipomas on the adjacent structures. The patient may describe a simple throat discomfort, a pharyngeal foreign body sensation or heaviness, dysphagia, and swallowing difficulty. Furthermore, some may experience life-threatening dyspnea, especially in the pedunculated forms, due to laryngeal obstruction, a complete externalization through the oropharynx as the case described by Gilberto et al. [9], or in the huge compressive forms. In this context, one case of death has been reported following asphyxia which was secondary to a voluminous and obstructive hypopharyngeal lipoma [10]. On the optic endoscopy, the lipoma appears as a well-limited, round-shaped, submucosal mass. It may be pedunculated or sessile.

Histologically, simple lipomas can be distinguished, based on their stroma, from the other benign variants including myolipoma, chondrolipoma, angiomyolipoma, adenolipoma, myxolipoma, and spindle cell lipoma [11] on the one hand. On the other hand, it is also important to rule out some malignant histology types such as liposarcoma in particular the well-differentiated cell form [12].

Concerning radiology features, lipoma is typically a well-circumscribed, round-shaped mass with homogeneous characteristics corresponding to a fat imaging with a thin capsule, very thin septa (< 2 mm), and some scattered small areas of soft tissue density. On ultrasounds, they are mostly isoechoic (28–60%) and hyperechoic (20–50%), yet they are hypoechoic in about 20% of the time [1] with no acoustic shadowing and no or minimal color Doppler flow [13]. If encapsulated, the capsule may be difficult to identify sometimes and to be distinguished from the air around in the pharyngolaryngeal area [7]. Calcification may also be present in up to 11% of cases, although more commonly associated with well-differentiated liposarcoma [7]. Moreover, avidly enhancing, thick/nodular septa or evidence of local invasion in addition to heterogeneous echotexture, more than minimal color Doppler flow, suggests malignancy.

The diagnosis is usually indicated by clinical features and ultrasound results. However, in the upper aerodigestive tract, CT scan and MRI imaging may be helpful for a better evaluation of the mass and the surrounding structures. On CT scan, lipomas presented as fatty, homogeneous, low-attenuation masses with minimal internal soft tissue component occasionally. It may also show some areas of fat necrosis, blood vessels, and muscle fibers whereas a liposarcoma is eliminated firstly [7]. MRI can also be used as a diagnosis tool and show a high-signal mass on both T1 and T2 with saturation on fat-saturated sequences. In fact, MRI represents the main imaging tool for lipoma diagnosis with or without atypical features. As a matter of fact, when no suspicious features are present, MRI is 100% specific regarding the diagnosis of lipoma [14]. In the opposite case, if suspicious features of malignancy are present, the specificity of MRI is lower since some masses with atypical features will nonetheless be simple lipomas, while the sensitivity is still 100% [14].

Well-differentiated liposarcomas, which represent the main and most dangerous differential diagnosis of lipomas, have high chances of local recurrence and a possibility of delayed dedifferentiation after the initial treatment [15]. Because of the differences not only in the treatment’s modalities, but also concerning the prognosis and the follow-up protocols, it is very important to distinguish simple lipomas from well-differentiated liposarcomas. In fact, immunohistochemistry describes the liposarcoma subtypes disclosing different morphologies, genetics, clinical behavior, pattern of disease progression, response to treatment, and 5-year survival rate [15, 16].

In the upper aerodigestive tract, surgical management presents a challenge regarding the security of the upper airways, the possibility of intubation, the possibility of jet ventilation use, and endoscopic surgery sittings. Since this is a rare entity, each case should be considered unique and have to be managed individually. Nonetheless, it seems that hypopharyngeal lipomas tend to rise from the post-cricoid region [15, 16]. Therefore, securing the upper airways might be challenging if the tumor is large and has no peduncle which implies a transitory tracheostomy. Also, the lent of the peduncle base might condition the necessity or not to put mucosal sutures or surgical glue in order to prevent salivary fistula. Surgical excision might be performed using endoscopic cold instruments (micro scissors, sickle). However, CO2 laser offers better ergonomics especially regarding bleeding control.

Table 1 summarizes all hypopharyngeal lipomas reported in the literature to date.

Conclusion

Pharyngeal lipomas are rare entities that might be life-threatening. Although clinical manifestations are not specific, imaging techniques, especially MRI, help set the diagnosis showing a fatty mass of the upper aerodigestive tract. However, pathology examination is crucial to rule out low-grade liposarcomas. Surgical management is not well-codified and has benefitted from the development of endoscopic techniques.

Patient’s perspective

I recently had breathing difficulty so I went seeing my cardiologist. After routine work up, he advised me to see an otolaryngologist as my results were normal. In the ORL outpatient clinic, doctor performed a fibro-endoscopy and discovered a tumor. I was scared of being diagnosed with cancer. I must say that I had swallowing difficulties that I didn’t took seriously. I had a CT scan and the ORL told me I had a fatty mass that he can remove pretty easily. I got the surgery. Post operatively, I had mild pain but my swallowing and breathing difficulties were resolved. I was discharged from the hospital within 3 days. I went back to see my doctor within 10 days for pathology results. He appeased my worries as the tumor was benign. Since surgery my breathing and swallowing symptoms were completely resolved.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient’s data confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Inampudi P, Jacobson JA, Fessell DP et al (2004) Soft-tissue lipomas: accuracy of sonography in diagnosis with pathologic correlation. Radiology 233(3):763–767. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2333031410

Pedeutour F, Foa C, Groupe francophone de cytogénétique oncologique (2002) Cytogenetics of adipose tissue tumors: benign adipose tissue tumors. Bull Cancer 89:689–695

Saurat JH, LaChapelle J, Lipsker D, Thomas L (2000) Dermatologie et infections sexuellement transmissibles. Elsevier Masson, Paris

Enzinger FM, Weiss SW (1995) Benign lipomatous tumors. In: Soft tissue tumors, 3rd edn, pp 381–430

Som PM, Scherl MP, Rao VM, Biller HF (1986) Rare presentations of ordinary lipomas of the head and neck: a review. Am J Neuroradiol 7(4):657–664

Barnes L (1985) Tumours and tumour-like lesions of the head and neck. In: Barnes L (ed) Surgical pathology of the head and neck, 1st edn. Dekker, New York, pp 747–582

Murphey MD, Carroll JF, Flemming DJ et al Benign musculoskeletal lipomatous lesions (From the archives of the AFIP). Radiographics 24(5):1433–1466. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.245045120

Salam GA (2002) Lipoma excision. Am Fam Physician 65:901–904

Acquaviva G et al (2016) Lipoma of piriform sinus: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Otolaryngol 2016:2521583, 4 pages. Hindawi Publishing Corporation. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2521583

Fyfe B, Mittleman RE (1991) Hypopharyngeal lipoma as a cause of sudden asphyxial death. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 12(1):82–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000433-199103000-00016 PMID: 2063825

Eckel HE, Jungehulsing M (1994) Lipoma of the hypopharynx: preoperative diagnosis and transoral resection. J Laryngol Otol 108(2):174–177

Wenig BM (1995) Lipomas of the larynx and hypopharynx: a review of the literature with the addition of three new cases. J Laryngol Otol 109(4):353–357

DiDomenico P, Middleton W (2014) Sonographic evaluation of palpable superficial masses. Radiol Clin North Am 52(6):1295–1305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcl.2014.07.011

Gaskin CM, Helms CA (2004) Lipomas, lipoma variants, and well-differentiated liposarcomas (atypical lipomas): results of MRI evaluations of 126 consecutive fatty masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol 182(3):733–739

Weiss SW, Rao VK (1992) Well-differentiated liposarcoma (atypical lipoma) of deep soft tissue of the extremities, retroperitoneum, and miscellaneous sites: a follow-up study of 92 cases with analysis of the incidence of “dedifferentiation”. Am J Surg Pathol 16:1051–1058

Savoie A, Lester S (2021) Transoral laser resection of hypopharyngeal liposarcomas. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 103:e1–e3. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2020.0179

Kramer R (1934) Multiple fibrolipoma of the hypopharynx and esophagus. In: The seventeenth annual meeting of the American Bronchoscopic Society, Cleveland

Som ML, Wolff L (1952) Lipoma of the hypopharynx producing menacing symptoms. AMA Arch Otolaryngol 56(5):524–31. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.1952.00710020548008.

Olson DL, Dodds WJ, Stewart ET, Helm JF, Duncavage JA (1987) Pedunculated pharyngeal lipoma presenting as an esophageal polyp. Dysphagia 2:113–116

Nash M, Harrison T, Lucente FE (1989) Submucosal hypopharyngeal lipoma. Ear Nose Throat J. 68(6):465–468

Iwasaki Y, Kojima T, Miyazaki T, Yashiki M, Nakagawa I (1992) Asphyxial death by laryngopharyngeal tumor--two autopsy cases. Nihon Hoigaku Zasshi 46(5):317–320

Gutsch A, Kula-Perek K, Walczak W, Parafiniuk M (1993) Lipoma of the larynx and hypopharynx. Otolaryngol Pol 47(2):176–180

Hellín Meseguer D, García Ortega F, Merino Gálvez E (1994) Pharyngeal lipoma. An Otorrinolaringol Ibero Am 21(3):247–254

Zbären P, Läng H, Becker M (1995) Rare benign neoplasms of the larynx: rhabdomyoma and lipoma. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 57(6):351–355

Aland JW (1996) Retropharyngeal lipoma causing symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 114:628–630

Welinder NR, Ibsen M, Andreassen UK, Berthelsen PG (1996) Large epiglottic lipoma. Intubation method for large tumors in the pharynx and larynx [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger 158(23):3325–3327

Gao Z, Zhang Y, Zhang L (1997) The clinical and pathological features of the hypopharyngeal lipomas [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao 19(1):78–80

Nwaorgu OGB, Akang EEU, Ahmad BM, Nwachokor FN, Olu-Eddo AN (1997) Pharyngeal lipoma with cartilaginous metaplasia (chondrolipoma): a case report and literature review. J Laryngol Otol 111(07). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022215100138241

Nishimura T (1998) Pharyngeal large lipoma with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pract Otorhinolaryngol 91(11):1088–1089. https://doi.org/10.5631/jibirin.91.1088

Barry B, Charlier JB, Ameline E et al (2000) Retro-pharyngeal and pharyngeal-laryngeal lipomas [in French]. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac 117(5):322–326

Jungehülsing M, Fischbach R, Pototschnig C et al (2000) Rare benign tumors: laryngeal and hypopharyngeal lipomata. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 109(3):301–305

Maged A, Riad M (2000) Laryngeal lipoma. CME Bull Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 4(1):17

Srinivasan V, Davies JE (2000) Snoring with sleep apnoea: deceptive appearances. J R Soc Med 93(2):81–82

Nishiyama K, Takahashi H, Iguchi Y et al (2001) Direct laryngoscopic extirpation and wound suture for hypopharyngeal lipoma: a case report [in Japanese]. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho 104(10):1044–1047

Cantarella G, Neglia CB, Civelli E, Roncoroni L, Radice F (2001) Spindle cell lipoma of the hypopharynx. Dysphagia 16(3):224–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-001-0066-8

Hockstein NG, Anderson TA, Moonis G, Gustafson KS, Mirza N (2002) Retropharyngeal lipoma causing obstructive sleep apnea: case report including five-year follow-up. Laryngoscope 112(9):1603–1605. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200209000-00013

Grützenmacher S, Lang C, Junghans D, Mlynski G (2002) Fibrolipoma of the larynx [in German]. Laryngorhinootologie 81(12):887–889

Miloudi Y, Bensaid A, El Harrar N (2005) The epiglottic lipoma: a rare cause of difficult intubation [letter]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 24(10):1316–1317

Singhal SK, Virk RS, Mohan H et al (2005) Myxolipoma of the epiglottis in an adult: a case report. Ear Nose Throat J 84(11):728 730, 734

Namyslowski G, Misiolek WSM, Lange NUD (2006) Huge retropharyngeal lipoma causing obstructive sleep apnea: a case report. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 263:738–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-006-0050-x

Dereköy FS, Fidan H, Fidan F et al (2007) Tonsillar lipoma causing difficult intubation: a case report. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg 17(6):329–332

Mitchell JE, Thorne JS, Hern JD (2007) Acute stridor caused by a previously asymptomatic large oropharyngeal spindle cell lipoma. Auris Nasus Larynx 34(4):549–552

Mattiola LR, Guerra de Sousa CI, Machado RB et al (2008) Laryngeal lipoma—a case report. Int. Arch Otorhinolaryngol 12(1):137–140

Minni A, Barbaro M, Vitolo D, Filipo R (2008) Ibernoma of the para-glottic space: an unusual tumour of the larynx. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 28(3):141–143

Perotti S, Vassalini M (2010) Sudden death due to a hypopharyngeal mass during sleep: a case report. Leg Med (Tokyo) 12(2):90–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.11.004 Epub 2010 Jan 27

Eyigor H, Suren D, Osma U et al (2011) A case of angiomyolipoma rarely located in the larynx. Case Rep Otolaryngol http://www.hindawi.com/crim/otolaryngology/2011/427074/. Accessed 15 Dec 2011

Evcimik MF, Ozkurt FE, Sapci T, Bozkurt Z (2011) Spindle cell lipoma of the hypopharynx. Int J Med Sci 8(6):479–481. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.8.479

Nader S, Nikakhlagh S, Rahim F, Fatehizade P (2012) Endolaryngeal lipoma: case report and literature review. Ear Nose Throat J 91(2):E18–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/014556131209100218. PMID: 22359140.

Peña-Valenzuela A, García León N (2012) Dysphagia caused by spindle cell lipoma of hypopharynx: presentation of clinical case and literature review. Case Rep Otolaryngol 2012:107383. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/107383

Lee HS, Koh MJ, Koh YW et al (2013) Transoral robotic surgery for huge spindle cell lipoma of the hypopharynx. J Craniofac Surg 24:1278–1279

D’Antonio A, Mottola G, Caleo A et al (2013) Spindle cell lipoma of the larynx. Ear Nose Throat J 92:E9–E11

Balasundaram A (2013) Hypopharyngeal lipoma causing obstructive sleep apnea: discovery on dental cone-beam CT. Ear Nose Throat J 92(3):E1–E4

Iwai K, Tomoda K, Nakai T, Kimura H (2015) A hypopharyngeal lipoma resulting in obstructive sleep apnea. Intern Med 54:2789–2790. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.54.4287

Wolf-Magele A, Schnabl J, Url C et al (2016) Acute dyspnea caused by a giant spindle cell lipoma of the larynx. Wien Klin Wochenschr 128:146–149

Al Abdulsalam A, Arafah M (2016) Dendritic fibromyxolipoma of the pyriform sinus: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Pathol 2016:7289017

Aydin U, Karakoc O, Binar M, Arslan F, Gerek M (2016) Intraoral excision of a huge retropharyngeal lipoma causing dysphagia and obstructive sleep apnea. Braz J Otorhinol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2016.10.011

Jabbr MS, Hamadi I, Fakoury MMA, Youssef GY (2017) Lipoma of right pyriform sinus. BMJ Case Rep 2017:bcr2017219872. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2017-219872

Jia W, Navaratnam A, Lingam RK (2018) Hypopharyngeal lupoma - a diagnostic work up. Wiley Clin Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.1592

Kram YA, McCann JM, Golden J, Wirtz E (2018) A rare cause of dysphagia: pyriform sinus atypical lipomatous tumor. Ear Nose Throat J 97(4-5):114–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145561318097004-507

Cukic O, Jovanovic M (2019) A case of hypoharyngeal lipoma with extrapharyngeal extension. Arch Head Neck Surg 48(1):e00232018. https://doi.org/10.4322/ahns.2019.0002

Liang Z, Zang Y, Jing Z, Zhang Y, Cao H, Zhou H (2021) Hypopharyngeal spindle cell lipoma: a case report and review of literature. Medicine 100(18):e25782. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000025782

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NO was involved in the diagnosis, surgery procedure, and manuscript drafting. OQ was involved in the literature review and drafting of the manuscript. NH was involved in the pathology study and reviewed the manuscript. OA was involved in the surgery procedure and reviewed the manuscript. MNA reviewed the manuscript for insightful remarks. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

An informed consent for publication purposes was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Video 1. Round shape mass filled the supraglottic region during inspiration.

Additional file 2: Video 2. The mass disappear during swallowing.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ouattassi, N., Qassab, O., Hammas, N. et al. Isolated hypopharynx lipoma: a case presentation and literature review. Egypt J Otolaryngol 38, 117 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-022-00305-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-022-00305-y