Abstract

Background

Delirium is a common geriatric problem associated with poor outcomes. Subsyndromal delirium (SSD) is characterized by the presence of certain symptoms of delirium yet, not satisfying the definition of full-blown delirium, defined by categorical elements, and is usually referred to as the presence of one or more symptoms in the confusion assessment method (CAM). This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and risk factors of delirium and SSD in older adults admitted to the hospital. Five hundred eighty-eight elderly (above 65 years) Egyptian patients were recruited from January 2019 to February 2020. After explaining the purpose of the study and assuring the confidentiality of all participants, an informed consent was obtained from the participant or a responsible care giver for those who were not able to give consent. All patients were subjected ‘on admission’ to thorough history taking, clinical examination, and comprehensive geriatric assessment including confusion assessment tools, mini-mental state examination, and functional assessment using Barthel index score.

Results

The current study showed that 19.6% of patients had delirium and 14.1% of patients had SSD with combined prevalence of 33.7%. Most common causes included metabolic, infection, organic brain syndrome, and dehydration. The current study reported significant proportionate relation between cognitive assessment and functional ability, so patients with a score of 23 MMSE had good functional ability, while cognitive assessment using mini-mental score shows inversed relation to delirium and SSD using CAM score.

Conclusion

Delirium is independently associated with adverse short-term and long-term outcomes, including an increase in mortality, length of hospital stay, discharge to an institution, and functional decline on discharge. Subsyndromal delirium (SSD) is characterized by the presence of certain symptoms of delirium, not yet satisfying the definition of full-blown delirium but it can identify patients with early cognitive and functional disabilities, and because of high prevalence of delirium and SSD. Efforts to prevent or early detection may identify patients who warrant clinical attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Delirium has many definitions, according to the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual on Mental Disorders (DSM-5), which describes delirium as a sudden and/or fluctuating shift in consciousness, arousal, and other cognitive impairments induced by physical disease or drugs [1, 2]; prevalence of delirium in elderly people as a whole is low (1–2%) but increases with age, rising to 14% among people over 85 years of age, and delirium is consistently linked to increased mortality, age, comorbidity, and acute illness [3]. It is also linked to prolonged hospital stay, new institutionalization, and patient and family distress [4, 5]. A significant proportion of medical inpatients with cognitive impairment may be affected by “subsyndromal” delirium (SSD), characterized by certain symptoms of delirium, but which does not develop to the full syndrome [6, 7]. Currently, there are no officially recognized diagnostic criteria for SSD, and two recent studies have provided differing definitions of SSD. It has been shown, however, that SSD is very common among older patients and may have negative prognostic significance [8]. The pathogenesis behind delirium is not fully known but it has postulated many mechanisms, including, systemic inflammatory cytokine response and disruption of the neurotransmitters [9]. Khurana et al. found that the most common etiologies of delirium in hospitalized elderly people in medical wards were sepsis and metabolic anomalies [10]. Most of the triggers were reversible and had a favorable outcome (recovered 83%), and clinical presentation of delirium is variable but can be broadly classified into three subtypes: hypoactive, hyperactive, and mixed based on patient’s psychomotor behavior [11]. Patients with hyperactive delirium display restlessness, agitation, and hypervigilance characteristics, and sometimes encounter hallucinations and delusions, where patients with hypoactive delirium, by contrast, present with lethargy and sedation, respond slowly to questions, and display little spontaneous motion. Hypoactive delirium is frequent in older patients and these patients are often misdiagnosed as having depression or a form of dementia. Mixed delirium patients display both hyperactive and hypoactive properties.

Confusion assessment method (CAM) is a screening tool used for delirium diagnosis. This instrument assesses the presence of intensity and fluctuation of nine symptoms of delirium: acute onset, inattention, disorganized thought, altered consciousness level, disorientation, memory impairment, perceptual disturbances, psychomotor agitation or retardation, and abnormal sleep-wake cycles, non-psychiatrist physicians can administer it in 5 min. The sensitivity of CAM has varied from 46 to 100% [12, 13]. Detection of cognitive impairments early can identify treatable conditions including ischemic brain disease, when risk factors can be then better controlled, helping to prevent progression of disease, the mini-mental state examination (MMSE), a 30-item interviewed administered assessment, is a validated and commonly used screening tool [14, 15], functional performance can be viewed as a measure of overall impact of health conditions in the context of a patient’s environment and social support system; therefore, it is essential to assess the patient’s functional status at the first visit, and any change in functional status should prompt further investigation. Barthel Index (BI) was developed as a measure of basic activity of daily living and assessment of disability in patients with neuromuscular and musculoskeletal conditions receiving hospital rehabilitation and was recommended for routine use by the Royal College of Physicians in the assessment of older people [16].

Aim

To evaluate the prevalence and risk factors of delirium and subsyndromal delirium in elderly Egyptian patients.

Methods

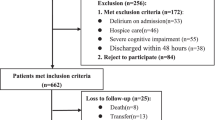

This prospective study included 588 elderly (above 65 years) Egyptian patients from January 2019 to February 2020. Patients who were admitted at intensive care units, coronary care units and acute stroke units, patients in coma, persistent vegetative state, chronic neurocognitive disorders, or taking antipsychotic medications were excluded. Patients were categorized according to their physiological age into young elderly patients (aged 65 to 74 years), middle elderly patients (aged 75 to 84 years), and very old (more than 85 years) patients. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or a responsible care giver for those who were not able to give consent. Patients were subjected to complete geriatric assessment including history taking and physical examination. All patients were screened for confusion using confusion assessment method (CAM), inattention, memory impairment, and altered consciousness according to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-III-R) within 6 h after admission and where divided into patients with delirium, subsyndromal delirium, and patients without delirium or SSD. Cognitive assessment was performed for cooperative patients using standard mini-mental state examination (MMSE). Basic activity of daily living and functional ability were screened ‘on admission’ using the Barthel index score. Comorbidities were quantified using the Charlson comorbidity index [17]. All scores were summed to provide a total score to predict mortality.

Statistical methods

Data management and statistical analysis

Data were pre-coded and entered using Microsoft Excel. Microsoft excel 2013 was used for data entry, and results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, minimum, maximum, or number (%). Comparison between categorical data [number (%)] was performed using chi-square test or Fisher exact test instead if cell count was less than five. Test of normality, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, was used to measure the distribution of data. Accordingly, data was normally distributed, so comparison between variables in the two groups was performed using unpaired t test. In more than two groups (three or more), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to compare between variables followed by LSD test, as a post hoc test, if significant results were recorded. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) computer program (version 19 windows) was used for data analysis.

P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

➣ To measure association between categorical variables: chi-square test or Fisher exact was done to compare between two independent percentages.

➣ Comparisons between two groups for normally distributed numeric variables were done using Student’s t test while for non-normally distributed numeric variables, comparisons were done by Mann-Whitney U test.

➣ Logistic regression was done to give adjusted odds ratio and magnitude of the effect of different factors.

➣ All tests were two-tailed and probability (P value) ≤ 0.05 is considered significant.

Results

Five hundred eighty-eight patients aged above 65 years with delirium and other comorbidities were recruited based on disturbance in attention and/or awareness that was accompanied with changes in baseline cognition not explained by any preexisting neurocognitive disorder. Their mean age was 70.09 years (SD ± 6.29 years), 58.5% of patients were males, and demographic data were shown in Table 1. Prevalence of delirium and subsyndromal delirium (SSD) was 19.6% (115 cases) and 14.1% (83 cases), respectively, in the young elderly group; 79 patients (68.7%) had delirium where 52 patients (62.7%) had SSD, in the middle elderly group; 29 patients (25.2%) had delirium and 27 patients (32.5%) had SSD, while in elderly group; 56 patients (48.7%) had delirium and 51 patients (61.4%) had SSD, 56% had hypoactive type of delirium whereas 20.2% had the hyperactive and 23.3% had mixed type, regarding cognitive assessment; 43 patients (7.3%) of cases had MMSE score less than 23, whereas 101 patients (17.2%) had score below 18, and 81 patients (13.8%) did not respond to MMSE. Common co-morbidities (Table 2) found included diabetes (42.5%), hypertension (34%), ischemic heart disease (27.2%), chronic liver disease (18.8%), chronic kidney disease (11.39%), asthma (5.2%), old cerebrovascular disease (5.1%), and malignancy (2.38%).

One hundred six patients had metabolic derangements causing delirium (67%; 77/115) and SSD (34.9%; 29/83) due to hepatic encephalopathy (26.7%) followed by uremic encephalopathy (17.17%), infectious etiologies affecting 31 patients causing delirium in 18 patients and SSD in 13 patients. Common infectious causes found in this study were chest infection (10%), hepatobiliary infections (3%), urinary tract infection (2%), and CNS infections (0.5%). Antidepressants and sedatives were among the most common causes (20.7%) of delirium and SSD in this study (Fig. 1). Most cases with hyperactive type of delirium were secondary to hepatic encephalopathy (61.5%), urinary tract infections (20%), while most patients with hypoactive type of delirium were secondary to uremic encephalopathy (20.2%), chest infections (19.3%), hypoglycemia (4.6%), antidepressants, and sedatives (3.7%) (Fig. 2).

In this study, mean values and SD of Barthel index were 15.88 ± 4.46 in patients with MMSE score above 23, whereas patients with MMSE score of 19–23, their mean and SD of BI were 11.65 ± 5.35, patients with MMSE score of 10–18 had mean and SD of BI were 10.69 ± 5.46, mean and SD of Barthel index were 7.86 ± 5.40 in patients with severe cognitive assessment by MMSE. Also in the current study, investigators showed that 69.6% of patients with delirium had severe cognitive impairment with MMSE score < 10, while 24.3% had MMSE score of 10–18, and 77.1% of patients with SSD had MMSE score of 10–18 (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the current study is considered the first Egyptian study investigating the prevalence of delirium and SSD. The prevalence of delirium alone was similar to the systemic review by Inouye et al. [18] who demonstrated 18–35% of patients admitted in general medicine and geriatric wards had delirium. Another study done by Meagher et al. [19] was performed in Ireland showing the prevalence of SSD was 7.7–13.2% which was slightly lower than our figures. In contrast, Velilla et al. [20] showed that in their study, the prevalence of delirium and SSD was 53% and 22.3%, respectively. Higher figures may be due to their longer (48 h) duration of follow-up compared to 6 h done in our study. Cole et al. [8] defined SSD by the presence of one or more of core symptoms including perceptual disturbances, inattention, and clouding of consciousness assessed by CAM. In our study, all patients with significant comorbidities by history were assessed using Charlson comorbidity index showing that most of them had diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic heart diseases, and chronic liver disease, and when patients were categorized into delirium and SSD, there was no significant difference in mean and SD of comorbidity indices in both groups. In addition, this study demonstrated significant predisposing risk factors for delirium showing that metabolic causes especially hepatic encephalopathy that was significantly associated with delirium than SSD; however, infections were associated equally with delirium and SSD.

This study showed also that when delirium was classified according to psychomotor activity. Hypoactive type was found to be more common in our study, and this agrees with the review done by Vaios P et al. [21]. They suggested that delirium occurring with metabolic disorders is mainly hypoactive type in contrast to the study done by Cerejeira J. and her colleagues [22]. They concluded that hyperactive type of delirium was considered the predominant type of delirium. The current study showed also that hepatic encephalopathy was associated with hyperactive type of delirium. This is against the study published by Coggins CC and his colleagues [23] that reported hepatic encephalopathy presenting with hypoactive delirium, cognitive assessment using mini-mental score shows inversed relation to delirium and SSD using CAM score and the relation is significant. This is in accordance with Khor et al. [24] who reported that 48.4% and 67.1% of patients had at least one feature of delirium on presentation to hospital from the CAM-S short and long severity scores, respectively, and the severity has also been shown to be inversely related to MMSE scores. Current study also showed significant inversed relation between cognitive assessment and functional disability, so patients with score of 23 MMSE had good functional ability. This is in agreement with Jakavonytė-Akstinienė et al. [25] where they reported a statistically significant correlation that was revealed between the scores of MMSE and BI (Pearson R = 0.41, P < 0.01); those with severe cognitive impairment were more dependent.

Conclusions

Subsyndromal delirium (SSD) is characterized by the presence of certain symptoms of delirium, which is not yet a satisfying definition of what a full-blown delirium is. It is not uncommon and high index of suspicion is required by general practitioner not only by geriatricians, but it can identify patients with early cognitive and functional disabilities because of the high prevalence and poor outcomes of delirium and SSD. The presence of even one or two symptoms of delirium may identify older people who warrant clinical attention, efforts to prevent, detect, and treat delirium and SSD must be justified.

Availability of data and materials

All raw data used in this study are available.

Abbreviations

- DSM-5:

-

The Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual on Mental Disorders

- SSD:

-

Subsyndromal delirium

- CAM:

-

Confusion and assessment

- MMSE:

-

Mini-mental state examination

- BI:

-

Barthel index

- DSM-III-R:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical manual of mental disorders

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS (2014) Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 383(9920):911–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1

Pendlebury ST, Lovett NG, Smith SC, Dutta N, Bendon C, Lloyd-Lavery A, Mehta Z, Rothwell PM. Observational, longitudinal study of delirium in consecutive unselected acute medical admissions: age-specific rates and associated factors, mortality and re-admission. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11):e007808.

Partridge JS, Martin FC, Harari D, Dhesi JK (2013) The delirium experience: what is the effect on patients, relatives and staff and what can be done to modify this? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 28(8):804–812. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3900

Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD (2006) Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing 35(4):350–364. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl005

Kiely DK, Bergmann MA, Murphy KM, Jones RN, Orav EJ, Marcantonio ER (2003) Delirium among newly admitted postacute facility patients: prevalence, symptoms, and severity. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Med Sci 58(5):M441–M445. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/58.5.M441

Ouimet S, Riker R, Bergeon N, Cossette M, Kavanagh B, Skrobik Y (2007) Subsyndromal delirium in the ICU: evidence for a disease spectrum. Intensive Care Med 33(6):1007–1013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0618-y

Cole MG, McCusker J, Voyer P, Monette J, Champoux N, Ciampi A, Vu M, Belzile E (2001) Subsyndromal delirium in older long-term care residents: incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 59(10):1829–1836

Van Gool WA, Van de Beek D, Eikelenboom P (2010) Systemic infection and delirium: when cytokines and acetylcholine collide. Lancet 375(9716):773–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61158-2

Khurana V, Gambhir IS, Kishore D (2001) Evaluation of delirium in elderly: a hospital-based study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 11(4):467–473

Lipowski ZJ (1983) Transient cognitive disorders (delirium, acute confusional sates) in the elderly. In: Psychosomatic medicine and liaison psychiatry. Springer, Boston, pp 289–306

Laurila JV, Pitkala KH, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS (2002) Confusion assessment method in the diagnostics of delirium among aged hospital patients: would it serve better in screening than as a diagnostic instrument? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 17(12):1112–1119. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.753

Rolfson DB, McElhaney JE, Jhangri GS, Rockwood K (1999) Validity of the confusion assessment method in detecting postoperative delirium in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr 11(4):431–438. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610299006043

Creavin ST, Wisniewski S, Noel-Storr AH et al (2016) Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) for the detection of dementia in clinically unevaluated people aged 65 and over in community and primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD011145

El-Hayeck R, Baddoura R, Wehbé A, Bassil N, Koussa S, Abou Khaled K, Richa S, Khoury R, Alameddine A, Sellal F (2019) An Arabic version of the mini-mental state examination for the Lebanese population: reliability, validity, and normative data. J Alzheimers Dis 71(2):525–540. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-181232 PMID: 31424409

Mahoney F, Barthel D (1965) Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index. MD State Med J 14:61–5.

Austin SR, Wong YN, Uzzo RG, Beck JR, Egleston BL (2015) Why summary comorbidity measures such as the Charlson comorbidity index and Elixhauser score work. Med Care 53(9):e65–e72. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318297429c

Inouye SK (1998) Delirium in hospitalized older patients: recognition and risk factors. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 11(3):118–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/089198879801100302

Meagher D (2009) Motor subtypes of delirium: past, present and future. Int Rev Psychiatry 21(1):59–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260802675460

Velilla NM, Bouzon CA, Contin KC, Beroiz BI, Herrero ÁC, Renedo JA (2012) Different functional outcomes in patients with delirium and subsyndromal delirium one month after hospital discharge. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 34(5-6):332–336. https://doi.org/10.1159/000345609

Peritogiannis V, Bolosi M, Lixouriotis C, Rizos DV (2015). Recent insights on prevalence and corelations of hypoactive delirium. Behav Neurol. 2015:416792.

Cerejeira J, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB (2011). A clinical update on delirium: from early recognition to effective management. Nurs Res Pract. 2011:875196.

Coggins CC, Curtiss CP (2013) Assessment and management of delirium: a focus on hepatic encephalopathy. Palliat Support Care 11(4):341–352. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951512000600

Khor HM, Ong HC, Tan BK, Low CM, Saedon NI, Tan KM, Chin AV, Kamaruzzaman SB, Tan MP (2019) Assessment of delirium using the confusion assessment method in older adult inpatients in Malaysia. Geriatrics 4(3):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics4030052

Jakavonytė-Akstinienė A, Dikčius V, Macijauskienė J (2018) Prognosis of treatment outcomes by cognitive and physical scales. Open Med 13(1):74–82. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2018-0011

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Submission declaration

This work has not been published previously, is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, its publication is approved by all authors and tacitly or explicitly by the responsible authorities where the work was carried out and, if accepted, will not be published elsewhere including electronically in the same form, in English or in any other language, without the written consent of the copyright-holder.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MH analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the comprehensive geriatric assessment. MM performed the study design, analysis of the results, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. FN collected patients’ data. AG supervised patient data collection validation and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or a responsible care giver for those who were not able to give consent; the study protocol conformed to ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the Internal Medicine Department Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, number: I-020417 April 2019.

Consent for publication

Written Consent for publication was obtained from patients or their care givers for patients who are unable to give consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare any financial and non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ibrahim, M.H.ED., Elmasry, M., Nagy, F. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of delirium and subsyndromal delirium in older adults. Egypt J Intern Med 33, 14 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43162-021-00042-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43162-021-00042-3