Abstract

Background

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) is a rare form of pulmonary hypertension characterized by remodelling of the pulmonary venules. PVOD and pulmonary arterial hypertension share similar clinical presentation. It is important to differentiate between these two conditions as PVOD carries a worse prognosis and life-threatening pulmonary oedema may occur following the initiation of conventional therapy.

Case presentation

We are reporting a case of pulmonary hypertension in a middle-aged lady who presented with hemoptysis and features of right heart failure. After extensive work up, no definite aetiology of pulmonary hypertension could be found out. Standard therapy did not cause any symptomatic improvement. After right heart catheterization, we got pre capillary pulmonary hypertension and along with typical findings in HRCT scan of thorax we established PVOD. We did not try lung biopsy as the procedure often lands up with complications. As we could not arrange for lung transplant we eventually lost the patient.

Conclusions

High suspicion and thorough systematic evaluation helped us to diagnose PVOD in this case. Thus, early diagnosis should be the primary aim in suspected cases of PVOD so that we can prepare for lung transplant at the earliest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) is a rare pulmonary microvasculopathy, characterized by occlusive fibrotic lesions, venous muscularization of septal and pre-septal veins and patchy capillary proliferation. The estimated prevalence of PVOD among patients clinically diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension (IPAH) varies from 5 to 20% [1]. Recessive mutations in epithelial translation initiator factor 2α K type 4 gene (EIF2AK4) which was co-segregated with PVOD are found in 100% of familial cases and 25% of sporadic cases of histologically confirmed PVOD [2]. We report a case of pulmonary hypertension in a middle-aged lady where we ruled out almost all common aetiologies and reached at the diagnosis of PVOD, though histopathological confirmation was not done.

Case presentation

A 48-year-old lady residing in a village in Eastern India presented to our hospital in April 2014 with progressive dyspnoea for 6 months, bipedal swelling for months and two episodes of hemoptysis in last week. Patient also gave a history of one episode of hemoptysis almost a year back which was not evaluated then. There was no history of chest pain, cough or palpitation. On repeated asking, she did not give any history of arthritis, rash or fever.

Examination showed tachycardia, tachypnoea and central cyanosis with oxygen saturation of 94% at room air in finger of non-dominant hand. Patient had elevated JVP of 8 cm with prominent c-v wave but normal blood pressure. Apical impulse was diffusely felt at left 5th intercostal space just outside the left mid clavicular line and we also got left parasternal heave. Pulmonary component of 2nd heart sound was palpable and loud. We got a pan-systolic murmur of grade 3/6 in the left parasternal area which increased with deep inspiration and passive leg rising. There was tender, pulsatile hepatomegaly with liver span of 18 cm. Breath sounds were normal, vesicular without any adventitious sound. There was no evidence of ascites.

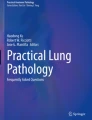

We started evaluation of this suspected case of pulmonary hypertension. Complete blood count was normal with haemoglobin of 14.5 g/dl, platelet count of 2.5 lakh/cmm and mildly raised ESR (35 mm/1st hour). Liver function tests showed altered albumin to globulin ratio (1:1) and prothrombin time was normal. USG whole abdomen revealed mildly coarse echotexture of liver but portal vein diameter and flow velocity was normal and there were no collaterals. Chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly with peripheral pruning of pulmonary vessels. ECG suggested right axis deviation with features of right ventricular hypertrophy. Echocardiography confirmed presence of dilated right atrium and ventricle, normal left ventricular ejection fraction (58%), but mean tricuspid regurgitation gradient of 62 mm of Hg without any other valve lesion. Though spirometry showed normal forced vital capacity (FVC), there was isolated reduction of diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) of 52% of predicted value. To find out the aetiology of pulmonary hypertension, we performed ANA, HPLC of Hb and HIV serology, but everything were normal. HRCT scan of thorax (Fig. 1) showed centrilobular ground glass opacities along with dilated pulmonary trunk. CT pulmonary angiography was normal and bubble contrast echocardiography showed no intra or extra-pulmonary shunt pathology. We could not perform ventilation perfusion scan as it was not available in our facility. In spite of our thorough evaluation, we could not find any aetiology. Though we started therapy with loop diuretic, digoxin and anticoagulation, our patient did not improve much and had another two episodes of moderate hemoptysis during her hospital stay. We planned for right heart catheterization. It showed mean pulmonary artery pressure of 42 mm of Hg with normal mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) of 11 mm of Hg. PCWP waveform (Fig. 2) was a flattened line with no respiratory variation. On the basis of HRCT of thorax and cardiac catheterization findings, we made the diagnosis of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. We did not opt for lung biopsy for the fear of serious complications and could not perform genetic study for EIF2AK4 gene mutation. In spite of all our attempts, patient gradually deteriorated, had several bouts of hemoptysis after 10 days and died.

Conclusions

PVOD is often a fatal disease frequently misdiagnosed as idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension. Though surgical lung biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis but it is usually avoided due to complications [3]. Heart failure and hemoptysis are the common complications which render high mortality in PVOD in spite of standard therapy of pulmonary hypertension, as evident from our case. Conventional treatment modalities are ineffective in the management of PVOD. Lung transplant is the only definitive management option at present and early identification with referral to a transplant centre is imperative. So, though PVOD is a rare cause of PH, it must be kept in the differential when common causes are ruled out.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- PVOD:

-

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease

- IPAH:

-

Idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension

- JVP:

-

Jugular venous pressure

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- DLCO:

-

Diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide

- ANA:

-

Antinuclear antibody

- HPLC:

-

High-performance liquid chromatography

- Hb:

-

Haemoglobin

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- PCWP:

-

Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

- Hg:

-

Mercury

References

Montani D, Price LC, Dorfmuller P et al (2009) Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur Respir J 33:189–200

Eyries M, Montani D, Girerd B et al (2014) EIF2AK4 mutations cause pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, a recessive form of pulmonary hypertension. Nat Genet 46:65–69

Montani D, Lau EM et al (2016) Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Eur Respir J 47:1518–1534

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

None to declare

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author 1 “AK” carried out the conception and literature review, analysed and interpreted the patient’s data and wrote the final manuscript. Author 2 “BB” contributed in the laboratory work and critical revision of the draft and shared in the final manuscript writing. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

At admission, the patient signed a generic informed consent for the treatment of personal data (without a specific indication of the present case report). The patient died, and the relatives of the deceased patient cannot be traced. The case report has been completely anonymized.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karmakar, A., Bhakat, B. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: a rare and enigmatic cause of pulmonary hypertension—a case report. Egypt J Intern Med 33, 6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43162-021-00034-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43162-021-00034-3