Abstract

Background

Nonimmune hydrops fetalis (NIHF) can be caused by different types of etiologies. Some rare intrathoracic lesions are associated with NIHF. Combination of mediastinal teratoma, NIHF, and chylothorax is extremely rare. Mediastinal teratomas which are located in midline should be difficult to be detected. Thoracic imaging should be performed with unknown etiology for hydrops, and in case of chylothorax, the presence of a mass compressing the ductus thoracicus should be considered primarily.

Case presentation

An infant was born with a diagnosis of NIHF. Bilateral chest tubes were inserted cause of bilateral pleural effusions. After enteral feeding, the previously clear pleural fluid became chylous. Medium-chain triglyceride infant formula and somatostatin analog octreotide were initiated. A mass was appeared on her neck with the disappearance of skin edema. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a large, heterogeneous mass which was suggesting immature teratoma originating from thyroid gland. Complete surgical excision of the mass was performed. Histology confirmed high-grade immature teratoma. The neonate made an uneventful recovery. Following complete cessation of pleural fluid drainage, octreotide was stopped. She was discharged home on exclusive breast milk on day 34 of life.

Conclusions

Mediastinal teratomas are rare masses that cause hydrops fetalis. Although the association of NIHF and mediastinal teratoma is rare, thoracic imaging can be performed if an etiology cannot be found despite basic evaluations for hydrops. In case of chylothorax, the presence of a mass compressing the ductus thoracicus should be considered primarily, and thoracic imaging should be performed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Backgrounds

Hydrops fetalis is the collection of excessive fluid in fetal cavities and soft tissue. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis (NIHF) accounts for almost 90% cases, and its prevalence ranges from 1/1500 to 1/4000 births [1, 2]. NIHF can be caused by different types of etiologies at various gestational ages. NIHF may occur secondary to congenital malformations such as cardiovascular, lymphatic, or gastrointestinal diseases, thoracic masses, urinary tract malformations, and extrathoracic tumors; also, some hematologic, infectious, chromosomal, syndromic, and metabolic disorders or twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome may cause NIHF, or it can be idiopathic [3].

Among large number of underlying etiologies, thoracic abnormalities including malformations and tumors account for 6% of cases. Intrathoracic lesions associated with NIHF are congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation, pulmonary sequestration, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, cardiac teratomas or rhabdomyomas, and mediastinal teratomas [3, 4].

Teratomas are one of the most frequent tumors of childhood. Sacrococcygeal teratomas are the most common type, whereas mediastinal teratomas are uncommon with a prevalence rate of less than 10%. Combination of mediastinal teratoma and NIHF is extremely rare [5, 6].

We here report a newborn diagnosed and treated for nonimmune hydrops and chylothorax caused by mediastinal teratoma.

Case presentation

A female infant was born at 35 weeks of gestation via cesarean section to a 35-year-old mother. The gestation period was uneventful with regular prenatal care. No abnormal finding was present on antenatal ultrasound imaging until 2 weeks before delivery. Ultrasonographic imaging which was performed at 33 weeks of gestation demonstrated fetal hydrops with bilateral pleural effusions, skin edema, and polyhydramnios.

The baby was born with a birth weight of 3170 g and Apgar scores of 3, 6, and 8 at 1, 5, and 10 min, respectively. She developed respiratory distress shortly after birth and could only be intubated with a size of 2.5 mm endotracheal tube. She had generalized skin edema and decreased breath sounds bilaterally. No dysmorphic features were noticed. Bilateral chest tubes were inserted through which 10 mL and 7 mL clear fluid were drained from the right and left pleural cavities, respectively.

Additional laboratory tests were performed in an attempt to detect a possible cause of nonimmune hydrops fetalis. There was no evidence of hemolysis or hyperbilirubinemia, and serum electrolytes, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, and liver enzymes were all normal. There was no metabolic acidosis. IgM antibodies for toxoplasmosis, rubella, and cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus were negative. The cranial ultrasound was normal, and the abdominal ultrasound demonstrated minimal ascite. Echocardiography ruled out any structural cardiac disease.

After 5 days from initiation of enteral feeding, the previously clear pleural fluid became chylous (glucose: 87 mg/dL; albumin: 1.95 g/dL; white blood cells: 7500/mm3 predominantly lymphocytes 85%; triglycerides: 546 mg/dL, negative culture for bacteria). Enteral feeding was continued with medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) infant formula, and an infusion of the somatostatin analog octreotide (Sandostatin, Novartis, Istanbul, Turkey) was initiated at a dosage of 3 μg/kg/h due to high volume of chylous pleural fluid drainage.

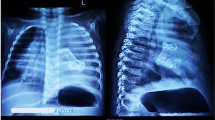

By day 8 of age, with the disappearance of skin edema, a mass was palped in the anterior of the baby. Ultrasound demonstrated a heterogeneous lobulated lesion including anechoic cystic components and hyperechoic calcifications with increased vascular flow which was located at the level of thymus. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a large, heterogeneous mass (42 × 35 × 28 mm) including cystic and necrotic areas localized in the middle and left of the neck, extending between hyoid bone and T3 vertebra, arching the vascular structures laterally especially on the left side, pushing the left brachiocephalic vein and arcus aorta caudally, and causing a tracheal shift to the right posterolateral side which was suggesting immature teratoma originating from thyroid gland (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). Serum tumor markers alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (ß-hCG) levels were unremarkable [AFP: 28100 ng/mL (normal range 1480–58887), ß-hCG: 1.18 mIU/mL (normal range 0–5 mIU/mL)].

Complete surgical excision of the mass (2 × 4 × 4 cm) was performed on day 19 of life. Histology confirmed high-grade immature teratoma originating from thyroid gland. The neonate was successfully extubated 4 days postoperatively and made an uneventful recovery. Following complete cessation of pleural fluid drainage, octreotide was stopped. Breast milk was gradually introduced by reducing MCT infant formula. She was discharged home on exclusive breast milk on day 34 of life. At follow-up, she remained asymptomatic. Chemotherapy was planned because histopathological evaluation was high-grade teratoma.

Discussion

Hydrops fetalis is the collection of excessive fluid in fetal cavities and soft tissue. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis (NIHF) accounts for almost 90% case. NIHF may occur secondary to congenital malformations such as cardiovascular, lymphatic, or gastrointestinal diseases, thoracic masses, urinary tract malformations, and extrathoracic tumors; also, some hematologic, infectious, chromosomal, syndromic, and metabolic disorders or twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome may cause NIHF, or it can be idiopathic [1, 4]. Among large number of underlying etiologies, thoracic abnormalities including malformations and tumors account for 6% of cases. Intrathoracic lesions associated with NIHF are congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation, pulmonary sequestration, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, cardiac teratomas or rhabdomyomas, and mediastinal teratomas [3, 6].

Teratomas are one of the most frequent tumors of childhood. Sacrococcygeal teratomas are the most common type, whereas mediastinal teratomas are uncommon with a prevalence rate of less than 10%. Mediastinal teratomas are commonly settle down around anterior and superior mediastinum and may be diagnosed as a mass in the chest during fetal period, most frequently during second and third trimester. Prenatal diagnosis of the mediastinal teratoma can be easily made using ultrasound, but some teratomas cannot be diagnosed in fetal life similar to our case. Despite advances prenatal imaging techniques, sometimes teratomas could not be detected by routine procedures. Some cases may be presented with respiratory distress in postnatal period, or the teratoma may be suspected when the calcified mass is diagnosed on chest graphy [5, 7]. In reported case, the infant needed urgent intubation at delivery room due to bilateral hydrothorax. The difficulty of intubation did not make us think of a mediastinal or neck mass due to skin and airway edema. Since the teratoma was located in the midline, no calcified mass was seen in serial chest radiography.

Combination of mediastinal teratoma and NIHF is extremely rare [6]. Fetal mediastinal teratomas are rare masses that cause hydrops fetalis or fetal demise in the prenatal period and respiratory distress in the neonatal period. Few cases of mediastinal teratoma presenting with NIHF have been reported so far in the literature. Some of them were treated with intrauterine procedures; some underwent surgical resection in postnatal period [8, 9]. The presented case was diagnosed as NIHF at prenatal period and was progressed to chylothorax within days let us think idiopathic congenital chylothorax, but the detection of the mediastinal mass was later found to be the cause of hydrops and chylothorax due to compression.

Although the association of NIHF and mediastinal teratoma is rare, thoracic imaging should be performed if an etiology cannot be found despite basic evaluations for hydrops. In case of chylothorax, the presence of a mass compressing the ductus thoracicus should be considered primarily, and thoracic imaging should be performed. The diagnosis and treatment processes could have become more complex, since clinical entities may be both the cause and result such as in reported case.

Availability of data and materials

Available upon request.

Abbreviations

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- ß-hCG:

-

Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin

- MCT:

-

Medium-chain triglyceride

- NIHF:

-

Nonimmune hydrops fetalis

References

Steurer MA, Peyvandi S, Baer RJ, et al. Epidemiology of live born infants with nonimmune hydrops fetalis—insights from a population-based dataset. J Pediatr. 2017;187:182–8.e183.

Sohan K, Carroll SG, Fuente SDL, et al. Analysis of outcome in hydrops fetalis in relation to gestational age at diagnosis, cause and treatment. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(8):726–30.

Bellini C, Hennekam RC, Fulcheri E, et al. Etiology of nonimmune hydrops fetalis: a systematic review. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:844–51.

Bellini C, Donarini G, Paladini D, et al. Etiology of non-immune hydrops fetalis: an update. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167:1082–8.

Paradies G, Zullino F, Orofino A, et al. Mediastinal teratomas in children. Case reports and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2013;84:395–403.

Wesolowski A, Piazza A. A case of mediastinal teratoma as a cause of nonimmune hydrops fetalis, and literature review. Am J Perinatol. 2008;25:507–12.

Giancotti A, La Torre R, Bevilacqua E, et al. Mediastinal masses: a case of fetal teratoma and literature review. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:384–7.

Merchant AM, Hedrick HL, Johnson MP, et al. Management of fetal mediastinal teratoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:228–31.

Agarwal A, Rosenkranz E, Yasin S, et al. EXIT procedure for fetal mediastinal teratoma with large pericardial effusion: a case report with review of literature. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2018;31:1099–103.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YEK and EO conceptualized and wrote the manuscript with orientation; EK, EO, and OE helped in the collection of literature search for the discussion; BD and OSF aided in the collection of images and design of the study; EE and AY are in the surgical team; KC is responsible for identifying and documenting the pathology; and BA and SA edited the manuscript with a bibliography check. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The patient’s parents gave written informed consent to publish the data contained within this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kostekci, Y.E., Kraja, E., Ergun, E. et al. Mediastinal teratoma presented with nonimmune hydrops and chylothorax: a case report. Ann Pediatr Surg 18, 49 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43159-022-00188-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43159-022-00188-x