Abstract

Background

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a condition resulting from fat aggregates in liver cells and is associated with metabolic syndrome, obesity, and oxidative stress. The present work was designed to investigate the role of celery and curcumin against high-fructose–high-fat (HFHF) diet-induced NAFLD in rats. Thirty male rats were classified into five groups: GP1: control group (rats were fed a normal control diet), GP2: HFHF group as a positive control (rats were fed a HFHF diet) for 20 weeks, GP3: HFHF + sily group, GP4: HFHF + celery group, and GP5: HFHF + cur group (rats in 3, 4, and 5 were treated as in the HFHF group for 16 weeks, then combined treatment daily by gavage for 4 weeks with either silymarin (as a reference drug, 50 mg/kg bw) or celery (300 mg/kg bw) or curcumin (200 mg/kg bw), respectively. The progression of NAFLD was evaluated by estimating tissue serum liver enzymes, glycemic profile, lipid profile, oxidative stress markers in liver tissue, and histopathological examination. Moreover, DNA fragmentation and the released lysosomal enzymes (acid phosphatase, β-galactosidase, and N-acetyl-B-glucosaminidase) were estimated.

Results

Our results showed that HFHF administration for 16 weeks caused liver enzymes elevation, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia. Furthermore, increased hepatic MDA levels along with a decline in GSH levels were observed in the HFHF group as compared to the control group. The results were confirmed by a histopathological study, which showed pathological changes in the HFHF group. DNA fragmentation was also observed, and the lysosomal enzyme activities were increased. On the other hand, oral supplementation of celery and cur improved all these changes compared with positive control groups and HFHF + sily (as a reference drug). Moreover, celery, as well as curcumin co-treatment, reduced HFHF-enhanced DNA fragmentation and inhibited elevated lysosomal enzymes. The celery combined treatment showed the most pronounced ameliorative impact, even more than silymarin did.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that celery and curcumin consumption may exhibit ameliorative impacts against NALFD progression, while celery showed more ameliorative effect in all parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Food and beverages rich in energy, fat, and/or sugar are now commonly consumed in modern societies. The large consumption of added sugar with low calories in processed or prepared foods, soft drinks, and colas is a phenomenon used in abundance recently [1].

The usage of fructose with high amounts as a sweetening substitute (fructose corn syrup) in the preparation of desserts and carbonated beverages may contribute to a high prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and metabolic syndrome around the world [1, 2]. Metabolic syndrome is a multifactorial disease and has risk factors related to hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, overweight, oxidative stress, and dyslipidemia [1]. Zarghani et al. [3] study reported that HFHF diet for 40 and 60 days induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in rats. Nowadays, functional foods, nutraceuticals, and medicinal herbs are used as an alternative to chemical drugs to decrease metabolic syndrome. It is considered as the source of natural active products that are different in mode of action and biological properties, antioxidant activity, and has a low level of side effects than chemical drugs [4,5,6].

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a spectrum of hepatic diseases associated with metabolic and cardiovascular disorders [3]. NAFLD is also characterized by atherogenic dyslipidemia, postprandial lipemia, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) dysfunction [7]. If this benign form of simple hepatic steatosis is not treated, it can progress to cirrhosis, which can lead to liver failure and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Dyslipidemia is manifested as increased serum triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels [8]. Controlled dyslipidemia in early stages resulted in a decrease in the occurrence of hepatic steatosis. Although a wide range of lipid-lowering agents are available, the metabolic complications associated with dyslipidemia persist [9].

Curcumin (Cur), a golden spice extracted from Curcuma longa, is the most active component of turmeric and is commonly used as a spice, food coloring agent, and in its application to improve the taste, color, and therapeutic properties in oral administration without any toxicity [10]. The desirable therapeutic traits of Cur are due to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, and hypoglycemic properties [9, 11, 12]. It also acts as a free radical scavenger, so it helps in inhibiting lipid peroxidation, and oxidative DNA damage.

Celery (Apium graveolens L., Apiaceae) is a yearly or perennial umbelliferous plant that is widely distributed throughout Europe and the tropical and subtropical regions of Africa and Asia [13]. Celery is considered an important source of phytochemicals such as phenolic acids, five flavonoid components (apigenin, hesperidin, luteolin, quercetin, and rosmarinic acid), and vitamins such as vitamin C and beta‐carotene (Pro-vitamin A) [14]. In addition, it contains folic acid, minerals (including sodium, potassium, calcium, and magnesium), silica, fiber, chlorophyll, and about 95% water and manganese. Many of the phytochemical compounds of celery have a role in decreasing oxidative damage because it is considered an antioxidant [15]. Celery phthalides lead to smooth muscle expansion in the blood vessels and lower blood pressure [16]. Additionally, it is used in dieting and weight loss programs [17]. Its leaves, roots, and seeds are used as food, seasoning in a daily diet, and as natural medicinal remedies around the world. The studied organs of A. graveolens (leaves, roots, seeds, and stalks) showed that the seeds contain the highest concentration of active compounds compared to other parts of the celery [13].

In this study, we sought to evaluate the potency of celery seeds extract and curcumin and compare between their impacts as dietary supplement in modulating biochemical markers of oxidative stress, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia in a high-fat–high-fructose diet-induced rodent model of NAFLD.

Methods

Chemicals

All were purchased from a local pharmacy, including curcumin 95% capsules (21st Century HealthCare, Inc., USA), celery seed extract (Natural Factors Nutritional Products Ltd., USA), fructose sugar (Unifructose, Unipharm, Egypt), and silymarin tablets (SIDECO, Egypt).

Animals

Thirty male rats (Sprague Dawley) were utilized in this work and were brought from the National Organization of Drug Control and Research (NODCAR), Egypt. The rats had an initial weight 120 ± 20 g. They remained in wire-bottomed cages made of stainless steel in the animal facility, where the temperature was maintained at approximately 24–25 °C with 12-h dark/light cycle. All animal experimentation protocols were carried out under the supervision of the Ethics Committee of the national organization of drug control and Research (NODCAR), Egypt, after the agreement of the general assembly of biological control and research.

Induction of NAFLD method

NAFLD was induced by feeding rats with a high-fat–high-fat diet (HFHFD) with the following macronutrients composition: containing 21.4% fat, 17.5% protein, 50% carbohydrate, 3.5% fiber, and 4.1% ash, concurrently with 20% of fructose in drinking water for 16 weeks as described by Lozano et al. [1].

Experimental design

After 1 week on a based diet, the experimental animals' body weight was classified into five groups, with six animals per group for a study period of 20 weeks. The first group had free access to a standard diet “Normal Diet” (con), with the following macronutrient composition: 3.1 % fat, 16.1 % protein, 3.9 % fiber, and 5.1 % ash (minerals), while the second group “High Fructose–High Fat” (HFHF), as described before, for 16 weeks, followed by 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) for 4 weeks. The third group (HFHF+sily), fourth (HFHF+Celery), and fifth (HFHF+Cur) were treated as in the HFHF group for 16 weeks and then combined treatment for 4 weeks with either silymarin (as a reference drug) (50 mg\kg bw) orally per day [18] or celery seed extract (300 mg/kg bw) [15] orally per day, or curcumin (200 mg\kg.bw) all dissolved in 0.5% CMC [19].

Body weight, liver weight, and liver index

At the termination of the experiment, all rats were weighted and then anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg b.w.) and killed. Initial and final body weights were reported, and body weight gain was calculated by the difference between the initial and final weights.

The liver was removed and weighed; the liver index was calculated by the equation (liver weight/body weight) × 100).

Blood sampling and tissue preparation

Blood was collected from the retro-orbital vein, left for 30 min at room temperature, and then centrifuged at 2000g for 15 min at 4 °C for serum separation to use in biochemical examinations.

Small pieces (about 0.5 cm in thickness) from the liver of each group were kept in fixative for histological examination; some pieces were subjected to DNA fragmentation and for lysosomal enzyme activities. The remaining tissue was homogenized in 10% Kcl on the ice by an electric homogenizer and then centrifuged at 4 °C by a cooling centrifuge. The supernatant is then collected to perform oxidative stress examinations.

Biochemical examinations

Biochemical examinations estimated serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) and glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT) by using kinetic commercial kits (Spinreact©, Spain) according to Burtis et al. [20]. Lipid profile parameters were estimated by commercial kits (Bio Diagnostic, Egypt); total cholesterol (S.TC) was evaluated according to Allain et al. [21]; triglycerides (S.TG) were estimated according to Fossati et al. [22], and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) was measured by using colorimetric kit (Bio Diagnostic, Egypt) [23].

Glycemic parameters

Fasting blood glucose (FBG) was assessed by a colorimetric kit (Bio Diagnostic, Egypt), and fasting blood insulin (FBI) using Rat ELISA Kits (Novus Biologicals, USA) according to the manufacturer's guide.

\({\mathrm{HOMA}}\text{-}{\mathrm{IR\,calculated\,from\,equation}} = {\mathrm{ FBG}}\backslash {\mathrm{FBI}} \times 22.5\) [24]

Oxidative stress parameters

MDA and GSH in liver tissue were performed by HPLC according to the methods of Karatas et al. [25] and Appala et al. [26].

Preparation of lysosomal fraction

Lysosomal fraction was prepared according to the method of Tanaka and Iizuka [27]. The activities of three lysosomal acid phosphatase (ACP), N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase (B-NAG), and β-galactosidase (B-GAL) were measured according to the method described by Ahmed et al. [28].

DNA fragmentation assay using agarose gel electrophoresis

DNA extraction and detection of apoptosis (DNA fragmentation assay) were done according to the “salting out extraction method” of Aljanabi and Martinez [29] with some modifications of Hassab El-Nabi et al. [30].

The isolated genomic DNA of the experimental animals was fractionated on 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis [31]; about 15 μg of the sample with 5 μl of the loading dye and marker DNA were loaded carefully into the respective wells without disturbing the gel. After conducting the electrophoresis at 50 mV, agarose gel was photographed using a gel doc.

Histopathological examination

The tissue that is kept in 10% formalin is processed according to the Bancroft technique [32] and then examined under a light microscope.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA 92108) version 6.05 was used to analyze the data. Results were presented as the mean ± standard error (SE). The statistical analyses were performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test followed by Tukey’s multiple range tests to compare between different groups corresponding to the control group and in-between. P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant, while P value > 0.05 was considered insignificant.

Results

Effect of HFHF alone or in combination with silymarin, curcumin, and celery on body weight, body weight gain, liver weight, and liver index

The data given in Table 1 reported that the HFHF diet exhibited a significant increase in weight gain, liver weights, and liver index as compared to the control group, while co-treatment with either curcumin or celery showed a significant reduction in body weight gain, liver weight as compared to the HFHF group.

On the other hand, curcumin co-treatment showed a significant reduction in liver index rather than the HFHF–celery group, due to the fact that the reduction in body weight was higher than the reduction in liver weight in the celery group.

Effect of HFHF alone or in combination with silymarin, curcumin, and celery on the activities of serum levels of GPT and GOT

Table 2 shows that the levels of serum GPT and GOT were all significantly elevated by HFHF (P < 0.05) in comparison with normal group, while the combined treatments of sily, cur, and celery against HFHF showed significantly reduced levels of GPT and GOT (P < 0.05) regarding the rats fed with HFHF. Meanwhile, the differences were significant between sily, cur, and celery-treated HFHF groups as compared with the normal control group (P < 0.05). As shown by the data, celery has a better effect than other treatments.

Effect of HFHF alone or in combination with silymarin, curcumin, and celery on the levels of glycemic profiles

When compared to the control rats, HFHF diet-fed rats reported a significant elevation in fasting blood glucose level (P < 0.05). However, co-treatment of HFHF with either cur or celery effectively suppressed the levels of glucose (P < 0.05), but the sily-treated HFHF group exhibited an insignificant difference when compared with HFHF rats (Table 2). Moreover, the levels of fasting blood glucose returned to close to the normal level in HFHF rats treated with celery.

In addition, fasting blood insulin levels were measured in fasted animals after 20 weeks. One-way ANOVA results showed that blood insulin levels significantly (P < 0.05) declined in the high-fructose–high-fat group compared to the control group (Table 2). However, the reduction in the fasting blood insulin was increased in the HFHF group receiving sily, cur, and celery as compared with the HFHF group (P < 0.05). Therefore, the level of fasting blood insulin reverted to close to the normal range in rats fed HFHF treated with celery.

Also, as shown in Table 2, HFHF-fed rats group showed significantly (P < 0.05) higher resistance in HOMA-IR in comparison with the control group. Moreover, sily-, cur-, and celery-treated HFHF groups exhibited significant differences when compared with HFHF-fed rats (P < 0.05).

Effect of HFHF alone or in combination with silymarin, curcumin, and celery on the serum levels of lipid profiles (total cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL)

As shown in Table 2, high-fat–high-fructose diet for 16 weeks mediated dyslipidemia, as one of the NAFD, which is reflected by significant elevation of serum levels of S.CH, S.TG, and significant reduction in HDL level when compared to the normal control rats (P < 0.05).

Oral administration of sliy has efficiently suppressed the serum CH and TG levels when co-treated with HFHF (P < 0.05), but it could not affect the serum HDL levels (P > 0.05). However, the administration of cur and celery to HFHF groups indicated that there was a significant reduction in S.CH, S.TG, and a significant elevation in HDL level as compared with rats fed on HFHF diet (P < 0.05). Notably, celery supplementation is superior in the improvement in dyslipidemia as all lipid profile parameters were reversed close to normal control levels.

Effect of HFHF alone or in combination with silymarin, curcumin, and celery on the levels of oxidative stress parameters (MDA and GSH)

The data in Table 2 show that the parameters such as levels of MDA and GSH were significantly different (P < 0.05) overall between the groups. The level of MDA was significantly increased in the HFHF group compared with the control group. In contrast, the level of GSH is significantly decreased (P < 0.05) in the same group. Oral administration of sily, cur, and celery reduced the elevation in MDA levels in association with a significant elevation in GSH levels when compared to HFHF group (P < 0.05). As shown, the administration of celery was a more pronounced effect than others on the oxidative parameters.

DNA fragmentation and lysosomal enzymes

The results investigated that in HFHF group, DNA damage was observed compared to negative control group, when animal treated with curcumin and celery in the damage in DNA decreased as compared to positive control and it provides the same result when compared to silymarin. The celery shows the best result among other groups (Fig. 1).

The effect of HFHF alone or in combination with celery, curcumin, and silymarin on three marker lysosomal enzymatic activities (ACP, acid phosphatase; β-GAL, β-galactosidase; and β-NAG,N-acetyl-B-glucosaminidase) in rat liver lysosomes. Data represented by mean ± SE. ɑp significant difference from control at P < 0.05. bp significant difference from HFHF at P < 0.05. cp significant difference between HFHF + Cur and HFHF + Celery groups at P < 0.05

The results indicated that hepatic lysosomal enzymes activities β-NAG, ACP, and β-GAL significantly increased regarding normal control. The HFHF + celery group showed the best result among the other treatments as compared to HFHF group (Fig. 2).

Histopathology examination

High-fructose–high-fat diet administration (Fig. 3b, c) caused liver steatosis, severe ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes, immune cell infiltration, binuclear hepatocytes, glycogenated nuclei that are mainly located in the area surrounding the portal tract, and Kupffer cells are seen. On the other hand, silymarin-treatment showed improvement in hepatic injury but lobular inflammation is still seen. Curcumin-treated group showed hepatic injury improvement, but sinusoidal dilatation is detected, while celery treatment showed normal architecture almost similar to control.

Histopathology of the liver from control rat (a) showed normal architecture of hepatocytes. HFHF diet rats (b, c) caused liver steatosis (black arrows), hepatocytes ballooning (b), green square boxes indicate immune cell infiltration, yellow circles indicate binuclear hepatocytes, black circles show that glycogenated nuclei are mainly located in the area surrounding the portal tract, and Kupffer cells (blue arrows). Silymarin-treated HFHF-challenged rat (d) showed normal hepatocytes but immune cell infiltration (green square) is seen, curcumin-treated HFHF-challenged rat showed hepatic sinusoidal dilatation (red arrows), (e) and celery-treated HFHF-challenged rat (f) normal architecture almost similar to control

Discussion

The high content of saturated fatty acids and fructose in the diet enhanced lipogenesis and insulin-signaling suppression. Furthermore, chronic intake of fructose is correlated with various signs of liver damage, as increased lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress, inflammation, insulin resistance in various tissues, and cellular necrosis. The extensive flow of fructose in the liver prompts a metabolic injury to its tissue [33].

In the current investigation, rats fed on high-fructose–high-fat diet (HFHF) for 16 weeks which is a well-established model for the induction of NAFLD [3]. The data reported in this study revealed that HFHF caused elevation in blood glucose, hypoinsulinemia, hyperlipidemia, and elevation of oxidative stress parameters.

The consumption of fructose molecules is rapidly absorbed through the glucose transporter-5 (GLUT5) and then absorbed by GLUT2 in the liver cells. In contrast, fructose actually cannot be absorbed by pancreatic beta cells due to the extremely low affinity of the pancreatic beta-cell for fructose, so fructose is unable to stimulate insulin secretion [34]. This finding is consistent with Basaranoglu et al. [35], which found that fructose consumption reduced plasma insulin by 24 h but elevated fasting glucose. In addition, Huang et al. [36] pointed out that a high-fructose diet may induce hypoinsulinemia, while a high-fat diet may alter the pancreatic function of insulin secretion and glucose intolerance, stating that the HFHF diet can have diverging effects on glucose metabolism in the rat.

Due to the severe side effects of pharmacologic agents, researchers are trying to use herbal extracts that have lower toxicity than chemical drugs in the treatment of various diseases.

Silymarin, a derivative of milk thistle (Silybum marianum), has been used for centuries as a natural cure for liver and bile duct disease. Consider the therapeutic potential of silymarin on hepatic steatosis with a high-fat diet (HFD)-induced non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis [37], and it is used in this study as a reference drug.

Apium graveolens has different therapeutic properties such as anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory activity, and antioxidant properties [5]. Flavonoids are among the secondary metabolites of compounds plant that cannot be synthesized by the human body and must be received through diet. Various plants, due to their phenolic content, are believed to enroll in the healing process of free-radical-mediated diseases; celery is among the plants that are rich in flavonoids such as apigenin, luteolin, and apiin [14].

In the recent study, serum glucose level in group receiving Apium seed extract indicated the efficacy in lowering blood glucose levels. The hypoglycemic impact of Apium seed may be due to enhanced secretion of insulin, proliferation, and repair of b-cells from free radical induced damage, increased glucose transport into cells and its utilization by tissues, increased glycogen synthesis from glucose in the liver, and improved oxidant–antioxidant balance [38].

Most of the administered fructose was converted rapidly into glucose by the liver [39]. Part of glucose reduced to sorbitol with aldose reductase, which cannot cross the cell membranes, and accumulated in cells. The increased accumulation of sorbitol and fructose in the rats maintained on a fructose-rich diet affects blood glucose level [40]. Therefore, apigenin and luteolin in celery seed can inhibit aldose reductase enzyme (the enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of glucose to sorbitol in the polyol pathway) [38].

On the other hand, curcumin is a polyphenol isolated from Curcuma longa which has been used as a potential therapeutic agent in some pathological conditions and against many diseases such as sepsis, hepatotoxicity, and neurotoxicity. In this concern, previous studies reported that administration of Curcuma longa improves blood glucose, insulin levels, and insulin resistance through several mechanisms that include the increased activity of glucokinase (GK) and glycogen content in the liver, the activation of glycolytic enzymes, and regulated the gluconeogenic enzymes by inhibition of glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) activities. Indirectly, curcumin diminishes free fatty acids in the liver and so lowers the stimulating of glucose production by liver [41].

In this study, HFHF caused liver damage and demonstrated considerable alternation in serum activity of liver enzymes. Moreover, Lemus-Conejo et al. [42] suggested that HFD-induced obese mice promotes a NAFLD which resulted in elevation in the activities of transaminases. Our study showed administration of celery-restrained GPT and GOT levels in serum as well as lysosomal enzymes in rats challenged by high-fructose–high-fat diet, which implies the repressed damage of liver cells and restoration of the cell membrane function. This may be reverted to its apigenin and lutein content which showed hepatoprotection, anti-oxidant, and anti-inflammatory [40]. Curcumin supplementation with HFHF diet decreased the GPT and GOT levels, so it acts as hepatoprotective prevented fructose-induced hepatotoxicity, leading to reducing the hepatic injury [43].

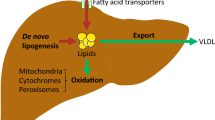

High-fructose–high-fat diet induces dyslipidemia, as excessive absorption of fatty acids in cells now has three different ways to get rid of: A portion of triglyceride deposition in hepatocytes, leading to NAFLD. Another part binds to apolipoprotein (ApoB) to produce VLDL; or part of them simply diffuse as free fatty acids in the blood circulation and trigger high cholesterol and dyslipidemia [44].

The data reported in this study showed significant elevation in S.CH, S.TG, and LDL and a remarked decrease in HDL in group administered with high fructose in concurrent with high-fat diet.

Due to primary metabolism of fructose in the liver, it may induce NAFLD by its ability to up-regulate de novo lipogenesis (DNL) and by bypassing the major rate-limiting step of glycolysis at phosphofructokinase. Fructose-induced DNL generates fatty acids that can then be incorporated into hepatic TGs or other lipid species. Fructose feeding has also been shown to induce the activation of carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein and increase the expression of lipogenic genes such as fatty acid synthase, acyl coenzyme-A carboxylase and stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase-1 in the fructose-fed rat [45].

This study indicates that celery extract markedly declined levels of S.CH, S.TG, and LDL, while elevated HDL. The phytochemical examination of A. graveolens indicated the presence of tannin, terpenoid, alkaloid, flavonoid, glycosides, and sterols, which may be responsible for its hypolipidemic activities. The mechanisms suggested for lipid-lowering action of Apium are inhibition of hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis, increasing fecal bile acid excretion, and enhancing plasma lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase activity and reduction of lipid absorption in the intestine [46]. On the other hand, blood lipids lowering impact was attributed to the compound 3n butylphthalideor (3nB) isolated from Apium graveolens; this results in agreement with the study of Iyer et al. [46]. In the recent study, curcumin supplementation to rats fed on HFHF diet reported significant lower levels of S.TC, S.TG, and LDL levels, but significant higher level of HDL regarding HFHF group. Our findings were in line with Abdel-Sattar et al. [47] who found the same results in fructose-fed rats with curcumin.

Previous study reported that curcumin enhances lipolysis and β-oxidation by up-regulating the expression of lipases such as adipose triglyceride lipase, hormone-sensitive lipase, adiponectin, and AMP-activated protein kinase [48]. In the same respect, curcumin stimulates the activity of hepatic cholesterol-7α-hydroxylase activity which promotes cholesterol catabolism [49].

Moreover, the progression of non-alcoholic steatosis to steatohepatitis has been linked to the action of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the liver. ROS lead to an increase in lipid peroxidation, damage of unsaturated lipids in cell membrane, and reduction in endogenous antioxidants, leading to liver tissue injury [50]. Moreover, fructose feeding has been shown to elevated oxidative stress and is associated with metabolic syndromes in rodents, as reviewed previously [51]. This agrees with our results which report that hepatic MDA was raised in rats fed on the HFHFD, indicating lipid peroxidation and the reduction in GSH as antioxidant.

Apium graveolens seed extract showed antioxidant activity represented by MDA reduction in addition to elevation of GSH level due to the presence of flavonoids, tannins, saponins, and luteolin [5]. Moreover, celery contains vitamin C that is a known booster of the immune system and reduces free radicals in the body [15]. The outcomes of the current study on the impact of celery seed extract on the oxidative stress parameters and DNA injury could potentially be due to the presence of sugar or secondary chains of amino acids (S) compounds.

Supplementation of curcumin reduced oxidative stress as it markedly diminishes hepatic MDA, while raised hepatic GSH in the curcumin–HFHF group in comparison with HFHF group. The MDA depletion and oxidative stress attenuation of curcumin may be through scavenging of superoxide anion (O2), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (HO•), and peroxyl radical (ROO•), and the activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), known as the master regulator of the endogenous antioxidant response, and downstream antioxidant genes. Therefore, the antioxidant property of curcumin helps in scavenging free radicals generated in various conditions associated with metabolic derangements [52].

DNA strand breaks when ROS interact with DNA and play an important role in initiation of apoptosis, which caused fragmented DNA pattern as detected by gel electrophoresis of liver tissue. The major lysosomal enzymes according to their importance as liver injury markers are: acid phosphatase (ACP), β-galactosidase, and N-acetyl-B-glucosaminidase [53]. In many pathological conditions, the loss of the stability of the lysosomal membrane takes place and then leakage of enzymes from lysosomes occurs. ACP is regarded as a hepatic lysosomes enzyme marker for measurement of cell viability, and the other lysosomal enzymes β-GAL, β-NAG, and β-GLU are highly important for liver lysosomal functions [54]. Abdel-Hamid et al. [55] investigated that lysosomal enzymes disorders contribute to several human diseases. A reduction in lysosomal stability is usually accompanied by an increase in lysosomal enzymatic activity in the extracellular fluid.

On the other hands, histopathological examination indicated the development of liver steatosis after HFHF administration; these data are in agreement with Kohli et al. [56]. However, curcumin-treated group showed hepatic injury improvement due to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and hepatoprotective impact as reported by Abdelrazek and Haredy [57]. Further, histopathological results of celery treatment group supported the improvement reported in biochemical examinations by showing normal architecture almost similar to control as reported previously by Cho BO et al. [14].

Conclusions

Based on the above results, it is concluded that continued consumption of HFHF appears to be contributing to the development of NAFLD and increasing the risk of progression to NASH. This is established by histopathological examination of the liver that reveals the development of liver steatosis and hepatocytes injury. Apium graveolens seed extract as well as curcumin co-supplementation ameliorated the negative influence of HFHF diet and recommended to be promising dietary supplementation against NAFLD progression. Finally, Apium graveolens showed more impact than curcumin, besides its low cost, high bioavailability, and least side effects.

Availability of data and materials

All materials are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ACP:

-

Acid phosphatase

- AMPK:

-

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- ApoB:

-

Apo-lipoprotein

- BWG:

-

Body weight gain

- CMC:

-

Carboxymethyl cellulose

- Cur:

-

Curcumin

- DNL:

-

De novo lipogenesis

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- FBI:

-

Fasting blood insulin

- FBW:

-

Final body weight

- FAs:

-

Free fatty acids

- G6Pase:

-

Glucose-6-phosphatase

- GLUT2:

-

Glucose transporter-2

- GLUT3:

-

Glucose transporter-3

- GLUT5:

-

Glucose transporter-5

- GK:

-

Glucokinase

- GOT:

-

Glutamic pyruvic transaminase

- GPT:

-

Glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase

- GSH:

-

Glutathione

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- HFD:

-

High-fat diet

- HFHF:

-

High fructose–high fat

- H2O2:

-

Hydrogen peroxide

- HO•:

-

Hydroxyl radical

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance

- HPLC:

-

High-performance liquid chromatography

- IBW:

-

Initial body weight

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- NAFLD:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- 3nB 3n:

-

Butylphthalideor

- NODCAR:

-

National Organization of Drug Control and Research

- Nrf 2:

-

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- O2 :

-

Superoxide anion

- PEPCK:

-

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase

- B-GAL:

-

β-Galactosidase

- B-NAG:

-

N-Acetyl-β-glucosaminidase

- ROO•:

-

Peroxyl radical

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- Sily:

-

Silymarin

- S.CH:

-

Cholesterol

- S.TG:

-

Triglyceride

- TAG:

-

Triacylglycerol

- T2D:

-

Type 2 diabetes

References

Lozano I, Van Der Werf R, Bietiger W, Seyfritz E, Peronet C, Pinget M, Jeandidier N, Maillard E, Marchioni E, Sigrist S, Dal S (2016) High-fructose and high-fat diet-induced disorders in rats: impact on diabetes risk, hepatic and vascular complications. Nutr Metab 13:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-016-0074-1

Ferder L, Ferder MD, Inserra F, Damián Ferder M, Inserra F (2010) The role of high-fructose corn syrup in metabolic syndrome and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 12:105–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-010-0097-3

Zarghani SS, Soraya H, Zarei L, Alizadeh M (2016) Comparison of three different diet-induced non alcoholic fatty liver disease protocols in rats: a pilot study. Pharm Sci 22:9–15. https://doi.org/10.15171/PS.2016.03

Krvavych A, Konechna R, Petrina R, Kyrka M, Zayarnuk N, Gulko R, Stadnytska N, Novikov V (2014) Phytochemical research of plant extracts and use in vitro culture in order to preserve rare wild species Gladiolus imbricatus. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci Phytochem 5:240–246

Kooti W, Daraei N (2017) A review of the antioxidant activity of celery (Apium graveolens L.). J Evid Based Complement Altern Med 22:1029–1034. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587217717415

Rouhi-Boroujeni H, Rouhi-Boroujeni H, Heidarian E, Mohammadizadeh F, Rafieian-Kopaei M (2015) Herbs with anti-lipid effects and their interactions with statins as a chemical antihyperlipidemia group drugs: A systematic review. ARYA Atheroscler 11:244–251

Ullah R, Rauf N, Nabi G, Ullah H, Shen Y, Zhou YD, Fu J (2019) Role of nutrition in the pathogenesis and prevention of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: recent updates. Int J Biol Sci 15:265–276. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.30121

Katsiki N, Mikhailidis D, Mantzoros C (2016) Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and dyslipidemia: an update. Metabolism 65:1109–1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.METABOL.2016.05.003

Maithilikarpagaselvi N, Sridhar MG, Swaminathan RP, Sripradha R, Badhe B (2016) Curcumin inhibits hyperlipidemia and hepatic fat accumulation in high-fructose-fed male Wistar rats. Pharm Biol 0209:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880209.2016.1187179

Said NI, Ibrahim SR, Abd-Elrazek AM (2019) Nano-curcumin versus curcumin in enhancement of the metabolic disorder in high fructose- and high-fat-fed male rats. Egypt J Med Sci 40(1):153–170

Trujillo J, Chirino YI, Molina-Jijón E, Andérica-Romero AC, Tapia E, Pedraza-Chaverrí J (2013) Renoprotective effect of the antioxidant curcumin: recent findings. Redox Biol 1:448–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2013.09.003

Kapoor P, Ansari MN, Bhandari U (2008) Modulatory effect of curcumin on methionine- induced hyperlipidemia and hyperhomocysteinemia in albino rats. Indian J Exp Biol 46:534–540

Tashakori-Sabzevar F, Razavi BM, Imenshahidi M, Daneshmandi M, Fatehi H, Entezari Sarkarizi Y, Mohajeri SA, Sarkarizi YE, Mohajeri SA (2016) Evaluation of mechanism for antihypertensive and vasorelaxant effects of hexanic and hydroalcoholic extracts of celery seed in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Braz J Pharmacogn 26:619–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjp.2016.05.012

Cho BO, Che DN, Shin JY, Kang HJ, Kim JH, Il JS (2020) Anti-obesity effects of enzyme-treated celery extract in mice fed with high-fat diet. J Food Biochem. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfbc.13105

Abdou HS (2012) Antioxidant effect of celery against carbontetrachloride induced hepatic damage in rats. Afr J Microbiol Res 6:5657–5667. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJMR12.637

Popoviç M, Kaurinoviç B, Triviç S, Mimica-Dukiç N, Bursaç M (2006) Effect of celery (Apium graveolens) extracts on some biochemical parameters of oxidative stress in mice treated with carbon tetrachloride. Phytother Res 20:531–537. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.1871

Hedayati N, Bemani Naeini M, Mohammadinejad A, Mohajeri SA (2019) Beneficial effects of celery (Apium graveolens) on metabolic syndrome: a review of the existing evidences. Phyther Res 33:3040–3053. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6492

ElMazoudy RH, Attia AA, El-Shenawy NS (2011) Protective role of propolis against reproductive toxicity of chlorpyrifos in male rats. Pestic Biochem Physiol 101:175–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pestbp.2011.09.003

El-Nabarawy S, Radwan O, El-Sisi S, Abd-Elrazek A (2015) Comparative study of some natural and artificial food coloring agents on hyperactivity, learning and memory performance in weanling rats. Int J Sci Basic Appl Res 21:309–324. https://doi.org/10.9790/3008-10238389

Burtis C, Ashwood E, Bruns D (2012) Tietz textbook of clinical chemistry and molecular diagnostics-e-book. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Allain CC, Poon LS, Chan CSG, Richmond W, Fu PC (1974) Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clin Chem 20:470–475. https://doi.org/10.1093/CLINCHEM/20.4.470

Fossati P, Prencipe L (1982) Serum triglycerides determined colorimetrically with an enzyme that produces hydrogen peroxide. Clin Chem 28:2077–2080. https://doi.org/10.1093/CLINCHEM/28.10.2077

Lopes-Virella MF, Stone P, Ellis S, Colwell JA (1977) Cholesterol determination in high-density lipoproteins separated by three different methods. Clin Chem 23:882–884. https://doi.org/10.1093/CLINCHEM/23.5.882

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC (1985) Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28:412–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00280883

Karatas F, Karatepe M, Baysar A (2002) Determination of free malondialdehyde in human serum by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem 311:76–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-2697(02)00387-1

Appala RVVSSN, Chigurupati S, Appala RVVSSN, Selvarajan KK, Mohammad JI (2016) A simple HPLC-UV method for the determination of glutathione in PC-12 cells. Scientifica (Cairo). https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6897890

Kiichiro T, Yoshio I (1968) Suppression of enzyme release from isolated rat liver lysosomes by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Biochem Pharmacol 17:2023–2032. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(68)90175-5

Ahmed NZ, Ahmed Z (2016) The lysosomal enzymatic activities and the digestive disorders on foot-mouth disease “FMD” in Egyptian dairy cows; buffalo; sheep “impaction, diarrhea and liver cirrhosis” of goats in serum. Int J Environ Sci 5:98–104

Aljanabi SM, Martinez I (1997) Universal and rapid salt-extraction of high quality genomic DNA for PCR-based techniques. Oxford University Press, Oxford

El-Nabi SEH, Elhassaneen YA (2008) Detection of DNA damage, molecular apoptosis and production of home-made ladder by using Simple techniques. Biotechnology 7:514–522. https://doi.org/10.3923/biotech.2008.514.522

Surzycki S (2000) Agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA. In: Surzycki S (ed) Basic techniques in molecular biology. Springer, Berlin, pp 163–191

Bancroft JD, Cook HC (1994) Manual of histological techniques and their diagnostic application, p 457

Cioffi F, Senese R, Lasala P, Ziello A, Mazzoli A, Crescenzo R, Liverini G, Lanni A, Goglia F, Iossa S (2017) Fructose-rich diet affects mitochondrial DNA damage and repair in rats. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9040323

Chyau CC, Wang HF, Zhang WJ, Chen CC, Huang SH, Chang CC, Peng RY (2020) Antrodan alleviates high-fat and high-fructose diet-induced fatty liver disease in C57BL/6 mice model via AMPK/Sirt1/SREBP-1c/PPARγ pathway. Int J Mol Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21010360

Basaranoglu M, Basaranoglu G, Bugianesi E (2015) Carbohydrate intake and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: fructose as a weapon of mass destruction. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 4:109–10916. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2014.11.05

Ammon HPT (1997) Hyper- and hypoinsulinemia in type-2 diabetes: what may be wrong in the secretory mechanism of the B-cell. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 105:43–47

Ni X, Wang H (2016) Silymarin attenuated hepatic steatosis through regulation of lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in a mouse model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Am J Transl Res 8:1073–1081

Niaz K, Gull S, Zia MA (2013) Antihyperglycemic/hypoglycemic effect of celery seeds (Ajwain/Ajmod) in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. J Rawalpindi Med Coll 17:134–137

Hotta N, Kakuta H, Fukasawa H, Kimura M, Koh N, Iida M, Terashima H, Morimura T, Sakamoto N (1985) Effects of a fructose-rich diet and the aldose reductase inhibitor, ONO-2235, on the development of diabetic neuropathy in streptozotocin-treated rats. Diabetologia 28:176–180

Tashakori-Sabzevar F, Ramezani M, Hosseinzadeh H, Parizadeh SMR, Movassaghi AR, Ghorbani A, Mohajeri SA (2016) Protective and hypoglycemic effects of celery seed on streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats: experimental and histopathological evaluation. Acta Diabetol 53:609–619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-016-0842-4

Den Hartogh DJ, Gabriel A, Tsiani E (2020) Antidiabetic properties of curcumin II: evidence from in vivo studies. Nutrients 12:58

Lemus-Conejo A, Grao-Cruces E, Toscano R, Varela LM, Claro C (2019) Lupine (Lupinus angustifolius L.) peptide prevents non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Food Funct 23:666

Abd-Elrazek AM, Mahmoud SMM, Abd ElMoneim AE (2020) The comparison between curcumin and propolis against sepsis-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in kidney of adult male rat. Futur J Pharm Sci 6:86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43094-020-00104-3

Radcke S, Dillon JF, Murray AL (2015) A systematic review of the prevalence of mildly abnormal liver function tests and associated health outcomes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 27:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000000233

Rodríguez-Calvo R, Barroso E, Serrano L, Coll T, Sánchez RM, Merlos M, Palomer X, Laguna JC, Vázquez-Carrera M (2009) Atorvastatin prevents carbohydrate response element binding protein activation in the fructose-fed rat by activating protein kinase A. Hepatology 49:106–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22570

Al-Kurdy M (2016) Effects of hydroalcoholic extract of celery (Apium graveolens) seed on blood & biochemical parameters of adult male rats. Vet Med Sci 7(1):89–95

Abdel-Sattar MH, El-Saeed MY, Al-Qulaly MMM (2016) Effects of curcuma longa (turmeric) extract or physical activity on certain metabolic aspects in obese adult male albino rats. Al-Azhar Med J 45:249–263. https://doi.org/10.12816/0029125

Kim JH, Yang HJ, Kim YJ, Park S, Lee OH, Kim KS, Kim MJ (2016) Korean turmeric is effective for dyslipidemia in human intervention study. J Ethn Foods 3:213–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2016.08.006

The effect of spices on cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase activity and on serum and hepatic cholesterol levels in the rat—PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1806542/. Accessed 3 July 2020

Jarukamjorn K, Jearapong N, Pimson C, Chatuphonprasert W (2016) A high-fat, high-fructose diet induces antioxidant imbalance and increases the risk and progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Scientifica (Cairo). https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5029414

Miller A, Adeli K (2008) Dietary fructose and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 24:204–209. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282f3f4c4

El-desoky F, Gaber AE, Shawky N, Ibrahim EE, Radwan S, Hesham M, Daba Y, Elrahman A, Yassin A, Hegazy GA (2018) Protective effect of caffeine and curcumin versus silymarin on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. Menoufia Med J 33:196–204. https://doi.org/10.4103/mmj.mmj

Said NI, Ibrahim SR, Abd-Elrazek AM (2019) Nano-curcumin versus curcumin in enhancement of the metabolic disorder in high fructose- and high-fat-fed male rat. Egypt J Med Sci 40:153–170

Ahmed NZ (2011) Anti-inflammatory effect of some natural flavonoids on the hepatic lysosomal enzymes in rats. New York Sci J 8:6–14

Abdel-Hamid NM, El-Moselhy MA, El-Baz A (2011) Hepatocyte lysosomal membrane stabilization by olive leaves against chemically induced hepatocellular neoplasia in rats. Int J Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/736581

Kohli R, Kirby M, Xanthakos SA, Softic S, Feldstein AE, Saxena V, Tang PH, Miles L, Miles MV, Balistreri WF, Woods SC, Seeley RJ (2010) High-fructose, medium chain trans fat diet induces liver fibrosis and elevates plasma coenzyme Q9 in a novel murine model of obesity and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 52:934–944. https://doi.org/10.1002/HEP.23797

Abdelrazek AM, Haredy SA (2019) The impact of L-carnitine and coenzyme Q10 as protection against busulfan-oxidative stress in the liver of adult rats. Nat Prod J 09:1–9. https://doi.org/10.2174/2210315509666190723131511

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMA, SRI, and HAE suggested the research point of the study, designed the experimental protocol, involved in the implementation of the overall study, performed the statistical analysis of the study, researched the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experimentation protocols were carried out under the supervision and approval of the Ethics Committee of the National Organization of Drug Control and Research (NODCAR), Egypt, with reference no. (NODCAR/II/32/2020).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abd‐Elrazek, A.M., Ibrahim, S.R. & El‐dash, H.A. The ameliorative effect of Apium graveolens & curcumin against Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease induced by high fructose-high fat diet in rats. Futur J Pharm Sci 8, 26 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43094-022-00416-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43094-022-00416-6