Abstract

This research intends to understand post-pandemic travel intention toward rural areas by extending the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Social media use (SMU) and electronic word of mouth (eWOM) have been incorporated into the original TPB model as additional constructs to increase its predictive power. To date, no study has measured post-pandemic travel intention in the Indian context utilizing a modified model of TPB taking the studied variables; thus, this study fills this void. A sample of 305 respondents was collected on a convenience basis via an online questionnaire. The targeted population of this study were the Indian social media users who follow the web pages of travel agencies. “SPSS 20” and “AMOS 22.0” were used for the statistical analysis. The results reveal that attitude (AT), subjective norm (SN), perceived behavioral control (PBC), social media usage (SMU) and electronic word of mouth (eWOM) all have a beneficial impact on post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations. These factors explained approximately 53% (R2 = 0.529) of the variance in the post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations. A number of theoretical and managerial ramifications can be deduced from the findings of this study. The novelty of this research lies in its integration of SMU and eWOM into the original TPB framework to assess individuals’ post-pandemic travel intentions toward rural destinations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The two intriguing topics that have been captivating the interest of tourism researchers are behavioral intention and motivation to travel [61]. The primary reason for this is that having a grasp of the behavioral intention of tourists may considerably cut down on superfluous marketing and promotional costs, which in turn makes a significant contribution in terms of the revenue generated by the tourism industry [7, 73, 88, 137]. Hence, it is essential to understand the determinants affecting tourist decisions, the creation of a belief/ attitude and the effect of different reference groups on tourist behavioral intention to make effective marketing plans and formulate adequate tourism policies post-COVID-19 [61]. These can be accomplished by understanding the factors influencing tourist behavior [110]. Because of this, the academic literature has a significant number of studies on tourist behavior and travel intention [2, 8, 13, 13, 14, 14, 61, 80, 99, 118, 120, 125, 126, 151]. In the recent past, researchers have paid a significant amount of attention, time and effort to study tourist behavior. Numerous empirical research has been conducted to assess tourists’ behavioral intentions and the effect of various elements that might alter such choices [13, 13, 14, 14, 61, 118, 125, 126]. Despite the innumerable empirical studies on the subject concerned, there is a dearth of studies that have measured post-pandemic travel intentions toward rural destinations. To date, no study has been carried out in India that looked at people’s intentions to travel to rural destinations post-pandemic. The current study analyzes post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations utilizing a modified model of the theory of planned behavior (TPB), thus covering this research gap previously left in the literature.

In developing and undeveloped countries, rural tourism is an important driving force of the economy [71]. The environmental impact of industrialized economies is of more concern [140]. Developing countries have prioritized economic sustainability during the pandemic [138]. According to World Bank Development Indicators, the majority of Indians reside in rural areas accounting for 65.07% in 2020 [132]. Rural destinations exhibit rural traditions, culture, folklore, art, etc., showcasing the rural lifestyle [93, 94]. It has the potential to harness the uniqueness that rural areas have got to offer to tourists by developing and promoting local products and services [93, 94]. Tourists who want to feel and experience authentic rural life live with the local people and participate in their daily routines. Such destinations offer tourists warm hospitality and a natural, earthy environment. The local population and industry gain from tourism in such rural areas [50]. The Ministry of Tourism has also undertaken the initiative and strategy to promote rural tourism across the country by releasing a draft of the national strategy and roadmap for developing rural tourism [70]. According to the report, tourist visits rural destination and imbibes their local customs and practices to experience their local culture, cuisine, traditions, etc. [108]. It is like leaving one’s lifestyle and adopting a new lifestyle to fit into their environment bubble. Urbanization has profoundly influenced economic growth and environmental viability in the last few years, but rural tourism has been gaining importance [141]. After the COVID-19 pandemic, people are finding a reason more desperately to move to rural areas because of the overcrowding of cities and towns, giving them less space for accommodation and the fast transmissibility rate of the infectious disease causing a major threat to humanity and its settlement [47, 134]. After the COVID-19-induced slowdown, China is the first major economy to recover, impacting others [139]. Therefore, it has become quite relevant to study post-pandemic travel intentions toward rural destinations, and the present study meets this emerging need.

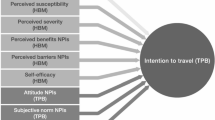

The number of studies utilizing the TPB paradigm has grown in recent years [2, 8, 80, 99, 118, 120, 151]. These studies focus on the intentions and behavior of tourists. Although the TPB model has been shown to be effective in predicting tourists’ intentions, many researchers still argue that it lacks adequate explanatory power [84, 99]. Some researchers believe the TPB model might benefit from including other essential constructs relevant to the tourism industry to strengthen its explanatory power [99, 149]. Ajzen [4] originally proposed the TPB model. This model posits three basic types of convictions that motivate human conduct based on behavioral, normative and subjective convictions [13, 14, 135]. Attitude (AT) is described by behavioral convictions, subjective norm (SN) is described by normative convictions, and perceived behavioral control (PBC) is described by subjective convictions [13, 14, 135]. Under the TPB model, three constructs affect the level of behavioral intention: AT, SN and PBC [4]. Moreover, after considering the preexisting variables, the TPB is open to adding new predictive factors if such components may capture a specified proportion of the variation of intention [5].

In light of the discussion, this research deepens our understanding of the factors influencing post-pandemic travel intentions to rural India by extending the TPB model. SMU and eWOM are added to the actual TPB model to expand it. This allows the model to more accurately reflect the likely thought process underlying post-pandemic plans for travel to India’s rural hotspots.

The following are some of the contributions that this study makes. First, it shows how SMU and eWOM affect post-pandemic travel intentions to rural India. These findings give a detailed understanding of tourists’ possible behaviors in the wake of a pandemic. Second, this research offers a reasonable basis for the TPB model’s viability in analyzing post-pandemic travel intentions to Indian rural destinations. It helps further to widen the range of applications for the TPB model. Third, the study offers a refined TPB model by including new constructs observed following the constructs of the original TPB model. Consequently, the ability of the basic TPB framework to explain and anticipate future traveling intentions is enhanced.

Theoretical background

Theory of planned behavior

Ajzen [4] proposed a model of planned behavior for better understanding and predicting human intention. This model postulates three components of BI, including AT, SN and PBC [45]. Due to its widespread usage and applicability, extensive research has been carried out across various disciplines to analyze and understand human behavior [1, 18, 38, 60]. Research in the tourism sector has been employing the TPB model to make similar predictions about tourists’ behavioral intentions [2, 8, 48, 76, 80, 99, 114, 118, 120, 136, 151]. Continuing previous research, the present study employs the TPB model to provide the basis for understanding post-pandemic travel intentions toward rural destinations in India. The other two key determinants incorporated in the TPB model are SMU and eWOM, which could help in better understanding the theoretical framework and ensure in giving futuristic results in order to predict the tourist intention. These variables were influential in current times [13, 13, 14, 14], which is why they have been incorporated into the original TPB model.

Behavioral intention (BI) was the term used by Fishbein and Ajzen [45] in the theory of reasoned action (TRA). BI is the primary variable in TRA to understand how consumers react toward a particular thing based on their beliefs and emotions [92]. Intention is defined as the action to perform a behavior in future [128]. Previous studies have shown that there is a connection between the traveler’s intention and the independent antecedents [91]. According to Fishbein and Ajzen [45], behavioral intention is a pivotal factor in deciding whether or not to travel. Earlier, this theory was used to predict the intention of travelers for various occasions and purposes. So TPB is applied in this study along with constructs viz., SMU and eWOM to help understand post-pandemic travel intentions toward rural destinations in India. Rural destinations with pleasant weather and living conditions are the preferable vacation choices for tourists. Locals provide a hospitable environment for tourists to have social interaction and authentic experiences with them [116]. According to Chen and Tsai [27], the behavior of tourists is the main determining factor in choosing a destination, visiting it, reviewing the services and products provided there and lastly, the intention to revisit a destination.

Based on the intention of the tourists, the results of this research will provide fresh perspective on how travel businesses can use social media to expand their marketing reach and win over new customers through online content and pages. The modified framework can also help industry experts and professionals to augment the marketing strategies to identify and promote rural destinations in India.

Hypotheses development

Attitude and post-pandemic travel intention

Attitude (AT) is the first important component of the TPB which measures the extent and assesses one’s behavior [45]. In the TRA, the concept of AT was utilized to illustrate how the decision-making process leads to the decision to travel to a specific destination. Decision-making is a complex process that is impacted by both psychological (i.e., AT) and societal (i.e., SN) factors [122]. A person’s favorable or adverse choice toward a specific action is termed as AT. Several studies suggest that AT positively influences BI [13, 14, 20, 61, 62, 72, 81, 100, 125, 126]. The post-pandemic travel intention will be determined by the AT of the tourists who are either willing or unwilling to travel. Few studies have investigated why people choose to travel to rural destinations where AT positively impacts the intention of the traveler [13, 14, 64, 72, 81, 113] (Table 1). Therefore, on the basis of the above discussion, the following hypothesis is postulated:

H1

Attitude significantly and positively influences post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations.

Subjective norm and post-pandemic travel intention

SN is another significant component of the TPB model. It is defined as the thoughts and feelings of those who matter to a person and have control over their choices. [45]. These significant individuals might be family members, close relatives, co-workers, acquaintances, or even business partners and associates [59, 61]. SN is defined as “the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behavior” [4]. Mathieson [103] states that “subjective norm reflects the perceived opinions of referent others. A ‘referent other’ is a person or group whose beliefs may be important to the individual” [103], p. 176). Another essential definition was provided by Fishbein and Ajzen [45], which is as follows: “the person’s perception that most people who are important to him/her think he/she should or should not perform the behavior in question.” SN is helpful in studying the influence which affects the traveler’s intention to perform a particular behavior in a given situation pertaining to the choices given by the family, friends and close ones [3]. There are significant studies that support the notion that SN is an essential factor that impacts tourist intention to visit a destination [13, 14, 61, 62, 72, 79, 81, 86, 122, 125, 126, 129, 146]. Rural tourism is one of the trending kinds of tourism where many studies are being carried out to improve and develop a place and community. Therefore, it becomes quite essential to study SN to understand post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations. Given the discussion above, the following assertion is postulated:

H2

Subjective norm significantly and positively influences post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations.

Perceived behavioral control and post-pandemic travel intention

Ajzen [4] identifies PBC as the third important factor in the TPB model, which assesses the potential of a person to behave in a certain circumstance. It is defined as “the perceived ease or difficulty of doing the behavior.” It describes the requirement of available resources, money and time [4]. The PBC assesses a person’s ability to regulate stimuli that either allow for or constrain the behavior that is required to cope with certain circumstances [136]. In other words, PBC should be considered to be maximum when a person has a reasonable and accessible number of opportunities and resources [102]. The significance of the ability in one’s behavior to perform or inhibit doing so, time, and other resources are actually responsible for predicting PBC [2]. It is essential for the formulation and execution of the intention to perform a behavior [4, 95]. In times of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was seen that PBC is important for predicting the behavioral intention of travelers [125]. Previous studies have demonstrated that PBC has been shown to play a significant role in making travel-related decisions [13, 14, 20, 61, 62, 72, 79, 81, 86, 100, 122, 125, 126, 129, 146]. Therefore, the hypothesis, based on the above discussion, is postulated as follows:

H3

Perceived behavioral control significantly and positively influences post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations.

eWOM and post-pandemic travel intention

TPB relies heavily on the concept of behavioral intention since it clarifies how an individual’s behavior reflects intention to engage in or abstain from a certain behavior [4]. It is important since it shows that eWOM has an effect on the purchase choices that individuals make [79]. The term “eWOM” is defined as “any positive or negative statement made by potential, actual, or former customers about a product which is made available to a multitude of people and institutes via the internet” [68]. The use of eWOM in the last few years has come out to be one of the critical factors in understanding consumer behavior and their buying decisions [79, 98]. eWOM is found to be more reliable and trustable with genuine opinions in comparison with traditional word of mouth [29, 75]. Travelers may now utilize eWOM, or electronic traveler’s testimonials, to express their impressions of a place online as a result of the development of the internet and information technology [13, 14]. The construction of a positive or negative perception of any destination is greatly influenced by eWOM, which also aids visitors in decision-making [21]. It is widely acknowledged as a major informational hub that significantly impacts tourists’ actual plans and top choices of hotels, restaurants and attractions [79, 121, 147]. The use of TPB to predict behavioral intention caused by eWOM has been the subject of many studies in the past [13, 14, 21, 95, 106]. According to earlier studies, intention and eWOM have a favorable relationship [11, 13, 14, 20, 66, 67, 79]. Therefore, the hypothesis, based on the above discussion, is postulated as follows:

H4

EWOM significantly and positively influences post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations.

Social media use and post-pandemic travel intention

Social media has been established as an essential online forum in recent years for the dissemination of information about travel, tourism and the hospitality industry [13, 14, 31]. Tourism and leisure industry marketers have taken notice of social media as a result of its rapid growth and widespread use [96]. There has been a renaissance in social media recently, with countless users sharing their experiences related to their recent visits [21, 28, 51]. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube, among others, have quickly become ubiquitous online tools for exchanging travel-related thoughts and stories online [51]). During the most recent pandemic, COVID-19, it has become clear that social media platforms are an extremely effective channel for the dissemination of information [13, 14, 87, 148] whether it is related to normal discussions, communications during a crisis, or decisions about travel and purchases. Social networking sites play a crucial role in the tourism industry, especially when it comes to planning tour arrangements [13, 13, 14, 14]. It provides a forum in which travelers may share their opinions and facilitates conversations among them in order to receive or disseminate information pertaining to travel [144].

Social media and user-generated content (UGC) through the use of smartphones have created a buzz in tourist destination places in India over the past few years [85, 145]. It helps in building a strong destination image and influences the behavior of those who wish to travel to such destinations. The use of social media has made people technologically more aware of places and more equipped with information about their destinations [33]. People plan their trips on the basis of information available to them through the internet [133]. Factors like tourist perception, traveler participation, travel reviews and expression of views through photograph or video uploads on social media have a crucial role in influencing and predicting visitors’ behavioral intentions via social media use [30, 32]. Tourists are also willing to share their good or bad experiences with others through social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, etc. [26]. A number of earlier studies have shown that the content of tourism-related postings shared via social media platforms has a substantial effect on the behavioral intention of tourists [13, 13, 14, 14], [81, 111, 127]. The following hypothesis is thus proposed based on the preceding discussion:

H5

Social media use significantly and positively influences post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations.

The hypotheses can be presented as shown in Fig. 1.

Research methods

Research instrument

Researchers first conducted a comprehensive literature review, and based on that a well-structured online questionnaire was developed using a seven-point Likert scale (where “1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree”). The Likert scale is used to rate the extent to which respondents agree or disagree with statements. It has been shown that items rated on a seven-point Likert scale are more accurate, simpler to operate and provide a better depiction of a respondent’s genuine assessment [6, 44, 83]. In addition to this, it has been shown that scales with seven points on the Likert scale work best for an online survey [90]. As a result, a Likert scale with seven points was employed in the present study, and only those items were taken into consideration that had been published in high-grade journals. Some minor changes have been made to the articulation and wording of the modified items just to make them appropriate to the context of the current study. The whole questionnaire was broken up into two separate sections. The very first section comprises questions on the demographics of the respondents, which include “gender,” “age,” “marital status,” “education” and “occupation.” The second section includes questions that measure the TPB’s basic constructs and two additional constructs: SMU and eWOM. Table 2 includes a list of the measurement items and their respective sources.

Data collection

Data were collected on a convenience basis via the use of an online questionnaire. It is a very quick and easy method for collecting samples [78]. In addition, online survey is also a convenient way to get in touch with a larger audience of similar interests [13, 13, 14, 14], [126]. In conjunction with convenience sampling, the snowball sampling technique was also employed to increase the participation rate. This is otherwise difficult to discover and identify potential respondents [36]. Researchers used a cross-sectional method for data collection. Using this method, data are collected from a number of distinct people at the same instant in time [119]. Before disseminating the questionnaire, it was decided to carry out a pilot test with a total of thirty participants to guarantee that the questions and language were uncomplicated and simple to understand for the respondents. After the pilot test yielded results that were accurate and acceptable, the link to the google form was uploaded on the social media websites of travel agencies from September 15, 2022 to October 31, 2022. The reason for choosing this time period lies in the fact that there was a notable decrease in the percentage of active cases that were COVID-19 positive as well as the overall number of current cases throughout the nation was also declining (The [131], Financial [43]) and the country had resumed all of the activities (The [131]). The google form link of the questionnaire was disseminated via the social media sites of some of the most well-known travel agencies, viz. “TravelGuru,” “Expedia,” “Goibibo,” “Thomas Cook,” “MakeMyTrip” and “Yatra.com” (Indian [77]). These are the leading travel agencies in India, contributing significantly to the economic growth and development of the country (Indian [77]). The target population of the study were Indian social media users who follow social media web pages of travel agencies. During the designated time period, a total of 354 responses were obtained; however, due to missing values, the researchers had to exclude 49 of those responses. Hence, a total of 305 responses that were considered to be legitimate were taken into consideration for final analysis.

Data analysis

Following the procedure outlined by Anderson and Gerbing [9], the researchers first employed CFA to determine the validity and reliability of the measurement model. CFA technique provides researchers with extensive tools for analyzing and upgrading theoretical models, which is one of the key reasons for employing this process [19, 23, 82]. After it was shown that the measurement model met the requirements, SEM was used in order to validate the assumptions and determine whether or not the suggested model was suitable. In SEM, several different indicators are utilized to quantify these latent variables, which might result in measurement errors. Therefore, SEM is the most important tool for analyzing and comprehending the connections between latent variables [25, 37, 52] and is determined to be relevant for the present study. A sample size of 1:10 is regarded adequate when utilizing SEM [53, 130, 143]. In addition, Comrey [34] recommended that a sample size of 300 is suitable for the purpose of carrying out factor analysis. In addition, Gorsuch [49] proposed that to do factor analysis, the ratio of participants to items should be either 5:1 or 10:1. The overall number of items in this study is 23, compared to the 305 participants in the sample. The number of participants in relation to the number of items is much higher than the suggested ratio. Consequently, the present study’s sample size (305) meets the criteria stated earlier and is adequate enough to let both factor analysis and structural equation modeling be carried out.

Results

Demographic profile of respondents

The participants of the present study were inbound tourists in the Indian context who intended to visit rural destinations in the post-pandemic period. It is evident from Table 3 that 65.6% of the respondents are male, while 34.4% are female. As many as 33.1% of the survey respondents come from the age group of 28–37, followed by 18–27 (22.6%). 57.4% of the respondents are married, and 37% of the respondents have acquired a postgraduate degree. The majority of those who participated in the survey are employed (38.7%), while 28.9% of the respondents are students. Please refer to Table 3 for more detail.

Descriptive statistics

All variables have standard deviations between 1.12137 and 2.02927, while the mean values vary from 4.1688 to 5.1821. Among all the variables, BI has the greatest mean value (5.1821), whereas SMU has the lowest (4.1688). Similarly, the resulting standard deviation is greatest for SMU (2.02927) and lowest for PBC (1.12137). Detailed information is given in Table 4.

Measurement model

AMOS 22 was used for the CFA that determined the component structure and validated the scale [22]. Researchers used CFA to analyze “convergent and discriminant validity conceptually” [81]. Khan et al. [87] state that convergent validity shows whether there is a significant correlation between the components of a measure. There are three requirements that must be met to ensure convergent validity [46]. To begin with, there is a requirement that all loadings on factors be more than 0.70. As for the second, composite reliability (CR) has to be more than 0.70 ([15, 35, 41, 58]), and last one is that the AVE for each construct must be more than 0.50 ([46, 58, 112]). Cronbach’s alpha must also be higher than 0.70 [112]. The present study was able to achieve those threshold limits, which are as follows: The factor loading runs between 0.755 and 0.946, the CR ranges between 0.901 and 0.958, and the AVE ranges between 0.735 and 0.850. In addition, CR must have a higher value than AVE. The conditions for convergent validity were, therefore, fully met. Nonetheless, the researchers assessed discriminant validity by determining whether AVE was higher than MSV. Within the scope of this study, the AVE values for all latent variables exceeded the MSV values. Hence, discriminant validity was also met in the present study. For detailed information, see Table 5.

To what extent do the measures of various conceptions vary from one another and have no commonalities is what is meant by the term “discriminant validity.” [87]. If the AVE is more than the square of the coefficient in each dimension and demonstrates how each dimension relates to the others, then discriminant validity is present [46]. Results showed that the total AVE value for all related constructs exceeded the square of the correlation between them. Discriminant validity was therefore established for the constructs used in the present study. Please refer to Table 6 for more detail.

Structure model

The qualitative evaluation process uses the measurement model to establish the constructs’ validity and reliability [69]. Thus, the researchers first used CFA in order to determine whether the hypothesized relationships between sets of variables were inevitable. The preliminary CFA results indicate a good model fit for the following indices (Table 7):

A few indices are produced by CFA statistics. Chi-square (CMIN/DF) analysis provides insight into the unique observed and projected covariance matrices which is 2.883. The absolute fit measure was assessed using CMIN/DF and RMSEA. Specifically, if CMIN/DF is less than 3 and RMSEA is less than 0.08, the fit is considered satisfactory, as per Kline [89]. In the present study, both indices are under the threshold limit. An incremental fit analysis was performed with the following indices: GFI = 0.901, TLI = 0.928, CFI = 0.939, NFI = 0.911, IFI = 0.940 and RFI = 0.900. Values of such indices greater than 0.80 are also considered acceptable, while a value of 0.90 is preferred [101, 104, 107, 142]. MacCallum et al. [101] state that an RMSEA of 0.08 or less indicates a mediocre fit. Please refer to Table 7 for more detail.

Hypotheses testing

It was analyzed to determine whether or not the hypothesized relationships between the components in the conceptual model were supported by the evidence provided by the measurement model’s reliability and validity. The standardized path coefficients and significance levels are two measures that were used to evaluate the quality of the inner model [57]. In order to assess the validity of the hypotheses that were presented, SEM path analysis was carried out (H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5). The path coefficient (Fig. 2 illustrates the magnitude of the association between the two hypotheses. Each of the five hypotheses is supported; hence, they are all accepted. All three of the TPB’s core constructs, AT (β = 0.397, t-value = 9.531, p < 0.001), SN (β = 0.247, t-value = 5.918, p < 0.001) and PBC (β = 0.128, t-value = 3.062, p = 0.002) are found to be statistically significant and positively affect post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations. Further, both SMU (β = 0.484, t-value = 11.613, p < 0.001) and eWOM (β = 0.426, t-value = 10.240, p < 0.001) have a significant and positive impact on post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations. All five hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5) are thus acknowledged as consistent with the data and are accepted. Please refer to Fig. 2 and Table 8 for more detail.

The findings illuminate all of the constructs that were under consideration, viz. AT, SN, PBC, SMU and eWOM significantly predict post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations. These factors explained approximately 53% (R2 = 0.529) of the variance in the post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations.

Among all the studied constructs, SMU came out as the most influential and strongest predictor of post-pandemic travel intention. This finding is different from the outcome of Joo et al. [81], which shows an insignificant association between SMU and travel intention. eWOM was the second most influential and strongest predictor of post-pandemic travel intention after SMU. This outcome aligns with the findings of Aviana and Alversia [12], Prayogo and Kusumawardhani [115]. AT came out as the third most influential predictor of post-pandemic travel intention. This outcome is opposite to the findings of Joo et al. [81], which show an insignificant association between attitude and travel intention. It was found that SN also has a significant influence on post-pandemic travel intention to rural destinations. This outcome aligns with the findings of Shang et al. [120] and Joo et al. [81]. The influence of PBC on post-pandemic travel intention was found to be the least as compared to other predictors, while in some previous studies, the effect was strong [81, 120]. The possible reason for these outcomes being different from the findings of previous studies could be because of different context. As a developing country, India has different socio-cultural and economic conditions than its developed counterparts, and the infrastructural facilities in India are also inadequate. Because of these factors, the influence of AT, SN and PBC could be different.

Discussion

The present study intended to understand how social media use and eWOM influenced post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations using the TPB. This study represents a significant advancement in the expansion and development of existing literature on tourist behavior, particularly with regard to overall tourist behavior [63]. This particular study provides valuable insights regarding post-pandemic travel intentions while expanding the TPB model through the inclusion of SMU and eWOM. This study could be distinguished from earlier research in many ways. First, the TPB model has been expanded, including two additional constructs, social media use and eWOM, which greatly improve the predictive power of the original TPB model. Second, by looking at post-pandemic travel intentions through the lens of TPB, which is a unique combination of the constructs, this research adds to the discussion of rural destinations, SMU and eWOM. Third, no study has been conducted in the Indian setting that has evaluated the impact of the TPB model, SMU and eWOM on post-pandemic travel intentions toward rural destinations. Fourth, there is a nascent but growing body of research on rural tourism in India. Hence, the present study addresses this gap by examining post-pandemic travel intentions and SMU in promoting rural tourism.

The present study examined the accuracy of a measuring model for reflective constructs by analyzing its “internal consistency, reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity” [56]. Once the measurement model was confirmed, the assumptions were tested using the structural model. The proposed model explained approximately 53% (R2 = 0.529) of the variance in post-pandemic travel intention to rural areas. This value was more than the minimum cut-off limit of R2 = 25% [55]. As a result, the model has an exceptionally high level of predictive relevance. Moreover, Armitage and Conner [10] state that “from a database of 185 independent studies published up to the end of 1997, the TPB accounted for 27% and 39% of the variance in behavior and intention, respectively,” and this study reports a variance of 53% in the post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations. Consequently, the validity of the expanded TPB model has been shown to have been confirmed by this research. In addition, 5000 repeats of nonparametric bootstrapping were employed to test the hypotheses [55]. As a consequence of this, all five hypotheses, from H1 to H5, were confirmed.

It is evident from the findings that out of all the model constructs, SMU is the most powerful and influential predictor of post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations, followed by eWOM, AT, SN and PBC, respectively. It has also been found that the original components of the TPB model, AT, SN and PBC have a considerable impact on post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations.

Post-pandemic travel intention is significantly and positively affected by AT (β = 0.397, t-value = 9.531, p < 0.001). This outcome is in accordance with earlier research [13, 14, 81, 105, 122, 125, 126]. It could be inferred from this finding that tourists have a positive outlook toward rural destinations in the post-pandemic period. Also, according to Sparks [123], “this is a pull-related notion that helps one maintain an optimistic attitude en route to a destination.” As a result, it may be deduced that tourists have an optimistic attitude toward rural destinations and intend to visit rural places after COVID-19.

SN also significantly and positively influences post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations (β = 0.247, t-value = 5.918, p < 0.001). This outcome is in accordance with earlier research [13, 14, 62, 81, 86, 122, 126, 146]. The possible explanation of SN to be significant could be that people are more likely to take others’ recommendations into account when making travel plans in the wake of a pandemic. Due to the quick-moving nature of data about COVID-19, tourists have a greater propensity to gravitate toward referent others. One further argument that might account for this is that when faced with a decision-making dilemma, Indians have a greater propensity to consult with one another. In India, decisions are often made using a collectivist cultural approach. A significant chunk of the participants in this survey is students. Since the opinions of referent others readily sway students, this could be one of the possible reasons for SN coming out as a powerful predictor of post-pandemic travel intention.

PBC also significantly and positively influences post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations (β = 0.128, t-value = 3.062, p = 0.002). This outcome is in accordance with earlier research [20, 62, 81, 86, 122, 146]. In this specific study, 65.6% of the participants are male, 33.1% are between the age of 28 and 37, and 32.1% have never been married. They are equipped with the necessary education to make their decisions on travel. As a result, it can be deduced that tourists do not believe that any barrier, whether related to education or another, prevents them from traveling to rural destinations after the pandemic. Moreover, tourism is an indispensable aspect of modern society, without which individuals would be unable to thrive. It requires various resources, viz. time, money, knowledge etc., to prepare a trip which makes an individual capable or incapable of visiting a particular destination.

In addition to the TPB’s core constructs, eWOM (β = 0.426) was the second most significant factor of post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations regarding its predictive power. This outcome is in accordance with the findings of Azhar, Ali, et al. [13] and Jalilvand and Samiei [79]. The possible explanation of this could be that to make post-pandemic travel decisions, tourists are more likely to consult eWOM in order to choose a tourism destination that is safe and secure. The formation of behavioral intention is largely influenced by a variety of factors, including “online ratings and reviews,” “referrals and recommendations” and “online forums and communities.” When it comes to selecting a destination that is safe and secure, tourists put a greater emphasis on eWOM. As a result, eWOM emerged as the factor with the highest predictive power of post-pandemic travel intention.

SMU (β = 0.484) was revealed as the most important and greatest predictor of post-pandemic travel intention toward rural places. This outcome is in accordance with the results of [14]. One potential explanation is that the rise in popularity of social media in recent years has attracted the attention of vacationers as they consider various aspects of their trips.

Conclusion

India is a growing South Asian nation with a very different culture and way of expressing emotions than those studied in earlier research. As a result, the TPB’s application in the South Asian area sheds new light on the model and provides new opportunities for researchers to investigate the TPB’s impact in more depth. This research adds to and broadens our understanding of the tourism industry generally by focusing on a developing country like India. Previous tourism research tended to focus on the developed world. Research conducted in one nation may not be generalized to other nations if the people there have different tastes and expectations based on a shared cultural or social standard. The findings of this research could be beneficial for social media advertisers and managers at both local and global levels who aim to target tourists and shape their inclination toward traveling. Further, these findings could be advantageous for individuals involved in managing rural tourism destinations, travel services, travel consultancy providers, and other related hospitality service providers. Enhancing comprehension and further developing the insights acquired from this research would enable stakeholders within the tourism sector of the nation to formulate effective strategies aimed at attaining a competitive edge within this profitable industry.

Theoretical implications

This study extends the scope of prior work that has used the idea of planned behavior in the field of rural tourism. The findings of this research have significant implications for the fields of rural tourism and post-pandemic travel intention by testing and validating the widely used TPB model with the inclusion of social media use and eWOM as additional constructs. This study lays the theoretical foundation for analyzing post-pandemic travel intentions in the context of rural tourism. From a psychological and technological standpoint, this study shows that the TPB model is relevant from the perspective of ICT. First, it integrates social media use and eWOM with the TPB model, expanding the previous research on post-pandemic travel intention toward rural places. This study is novel since it is the first of its kind to apply the TPB model to assess post-pandemic travel intentions to rural destinations in the Indian context, combining SMU and eWOM with the TPB. This work addresses a gap in the literature by providing sound theoretical backing for subsequent researchers and academicians. Second, the findings support the importance of eWOM and SMU in the TPB model for a holistic comprehension of the elements that influence potential travelers’ choices in the post-pandemic era. Finally, the augmented model clarifies the interplay between SMU and eWOM by outlining the factors influencing people’s travel decisions after a pandemic.

Practical implications

The results of this research have a number of managerial and practical ramifications. The findings that pertain to social media use and its influence on post-pandemic travel intention have significant ramifications for business managers. This is because social media use impacts tourists’ behavioral intention toward rural destinations. The enormous influence that social media use has on the behavioral intention of tourists emphasizes how important it is for business managers to take social media into serious consideration in order to sustain the tourism business in the post-pandemic period. Since social media has such a profound effect on consumers’ propensity to act, it is crucial to be current in providing pertinent information and to be easily visible in such tourist information searches. The results may be useful for local social media marketers who want to influence the decision-making process of tourists toward a destination. In particular, this study’s results may be valuable to people in the hospitality business who provide services to tourists in rural tourism destinations. This includes tour operators, hotels and travel agencies, among other potential service providers. Findings from this study might inform new policies, plans and strategies for the travel, tourism and hospitality industry in the nation, better meeting the needs of visitors from rural areas. Marketers need to recognize the value of social media, and they need to place a greater focus on the quality of the content that is posted on social media platforms in order to have a significant influence on the minds of consumers.

Results also showed that eWOM significantly influenced post-pandemic travel intention to rural areas. Therefore, efforts should be made to encourage positive eWOM among tourists about the rural destination. As a result, online marketers should pay careful attention to this particular area of concentration. In this context, businesses that provide services linked to travel and tourism need to strongly emphasize collecting timely feedback about their products and services to raise the bar for the quality of such offerings so that positive eWOM could be generated among tourists.

The third most crucial aspect in deciding post-pandemic travel intention is one’s attitude toward visiting rural areas. As a result, industry practitioners and marketers should make an effort to comprehend the elements that influence the attitude expressed on social media and adapt their marketing and promotional strategies appropriately. For this reason, it is possible to declare that in order to boost rural tourism, marketers should emphasize content over social media that forms an optimistic attitude toward rural destinations. Marketing strategies should be developed in such a manner that they may foster the social disposition and attitude of users and then explain the practical benefits of rural tourism rather than focusing only on the appeal of particular tourist sites. Additionally, as a growth objective, tourist agencies and experts should take a stand to protect the environment and local culture. This should be a priority for the tourism industry. The only way to guarantee that local resources will remain valued, the needs of rural visitors will be addressed, and rural tourism will continue to grow is to cultivate it in a manner that does not hurt the ecosystem of surroundings.

Limitations and future research directions

The current research aimed to utilize TPB as a lens to investigate post-pandemic travel intentions toward rural places in the Indian setting by adding two new components, namely SMU and eWOM. Although rendering several limitations, this study paves the ground for future research. First, this study used the TPB model to understand whether or not tourists would be interested in traveling to rural destinations in the post-pandemic period. In further research, other behavioral theories, such as behavioral reasoning theory (BRT) may be used to better predict travel intentions. Second, social media use and eWOM were considered to be additional constructs to the TPB model. In further research, it could be possible to examine travel intention by using other constructs, such as user-generated content (UGC) and the quality of content. Third, this study is of cross-sectional kind in its design. To get more robust findings in subsequent studies, a longitudinal study design could be used. Fourth, this study used a questionnaire method to collect the data. In subsequent research, a variety of methods for data collection could be used, such as the interview approach. Fifth, the inferences were drawn on the basis of 305 responses. In subsequent studies, larger sample sizes could be used in order to get generalized conclusions. Last, the context of this study is India which is a developing country. Future studies could be conducted in other developing/developed countries. This practice could produce different results.

Availability of data and materials

The authors declare that all types of data used in this study is available for any clarification. The authors of this manuscript are ready for any justification regarding the data set. To make available of the data set used in this study, the seeker must mail to the mentioned email address. The profile of the respondents is completely confidential.

References

Abamecha F, Tena A, Kiros G (2019) Psychographic predictors of intention to use cervical cancer screening services among women attending maternal and child health services in Southern Ethiopia: the theory of planned behavior (TPB) perspective. BMC Public Health 19:1–9

Abbasi GA, Kumaravelu J, Goh Y-N, Dara Singh KS (2021) Understanding the intention to revisit a destination by expanding the theory of planned behaviour (TPB). Spanish J Market - ESIC 25(2):282–311

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (1980) Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211

Ajzen I (2020) The theory of planned behavior: frequently asked questions. Human Behav Emerg Technol 2(4):314–324

Albert B, Tullis T (2013) Measuring the user experience: collecting, analyzing, and presenting usability metrics. Newnes, Oxford and Boston

Alegre J, Juaneda C (2006) Destination loyalty: consumers’ economic behavior. Ann Tour Res 33(3):684–706

Al-Khaldy DAW, Hassan TH, Abdou AH, Abdelmoaty MA, Salem AE (2022) The effects of social networking services on tourists’ intention to visit mega-events during the Riyadh season: a theory of planned behavior model. Sustainability 14(21):14481

Anderson JC, Gerbing DW (1988) Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull 103(3):411–423

Armitage CJ, Conner M (2001) Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol 40(4):471–499

Assaker G, O’Connor P (2021) eWOM platforms in moderating the relationships between political and terrorism risk, destination image, and travel intent: the case of Lebanon. J Travel Res 60(3):503–519

Aviana IAAD, Alversia Y (2019) Media effectiveness on destination image and tourists revisit intention: post-disaster in Bali. In: 33rd International business information management association conference: education excellence and innovation management through vision 2020, IBIMA 2019, International Business Information Management Association, IBIMA, pp. 5455–5467

Azhar M, Ali R, Hamid S, Akhtar MJ, Rahman MN (2022) Demystifying the effect of social media eWOM on revisit intention post-COVID-19: an extension of theory of planned behavior. Fut Business J 8(1):1–16

Azhar M, Hamid S, Akhtar MJ, Subhan M (2022) Delineating the influence of social media use on sustainable rural tourism: an application of TPB with place emotion. J Tour, Sustain Well-being 10(4):292–312

Bagozzi RP, Yi Y (1988) On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci 16(1):74–94

Bagozzi RP, Dholakia UM, Basuroy S (2003) How effortful decisions get enacted: the motivating role of decision processes, desires, and anticipated emotions. J Behav Decis Mak 16(4):273–295

Bambauer-Sachse S, Mangold S (2011) Brand equity dilution through negative online word-of-mouth communication. J Retail Consum Serv 18(1):38–45

Belanche D, Casalo LV, Flavian C (2019) Artificial intelligence in FinTech: understanding robo-advisors adoption among customers. Ind Manag Data Syst 19(7):1411–1430

Bentler PM (1983) Some contributions to efficient statistics in structural models: specification and estimation of moment structures. Psychometrika 48(4):493–517

Bianchi C, Milberg S, Cúneo A (2017) Understanding travelers’ intentions to visit a short versus long-haul emerging vacation destination: the case of Chile. Tour Manage 59:312–324

Bilal M, Akram U, Rasool H, Yang X, Tanveer Y (2021) Social commerce isn’t the cherry on the cake, its the new cake! How consumers’ attitudes and eWOM influence online purchase intention in China. Int J Qual Serv Sci 14(2):180–196

Brown TA (2015) Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford publications, New York City

Browne MW (1984) Asymptotically distribution-free methods for the analysis of covariance structures. Br J Math Stat Psychol 37(1):62–83

Byrne BM (1994) Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: basic concepts, applications, and programming. Sage, Newbury Park

Byrne BM (2010) Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (multivariate applications series), vol 396. Taylor & Francis Group, New York, p 7384

Casaló L, Flavián C, Guinalíu M (2010) Determinants of the intention to participate in firm-hosted online travel communities and effects on consumer behavioral intentions. Tour Manage 31(6):898–911

Chen C, Tsai D (2007) How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour Manage 28(4):1115–1122

Chen YC, Shang RA, Li MJ (2014) The effects of perceived relevance of travel blogs’ content on the behavioral intention to visit a tourist destination. Comput Hum Behav 30:787–799

Cheung CM, Thadani DR (2010) The effectiveness of electronic word-of-mouth communication: a literature analysis. Bled eConf 23:329–345

Cheunkamon E, Jomnonkwao S, Ratanavaraha V (2020) Determinant factors influencing thai tourists’ intentions to use social media for travel planning. Sustainability 12(18):1–21

Chu SC, Kim J (2018) The current state of knowledge on electronic word-of-mouth in advertising research. Int J Advert 37(1):1–13

Chung JY, Buhalis D (2008) Information needs in online social networks. Inf Technol Tour 10(4):267–281

Cinelli M, Quattrociocchi W, Galeazzi A, Valensise CM, Brugnoli E, Schmidt AL, Zola P, Zollo F, Scala A (2020) The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Sci Rep 10(1):1–10

Comrey AL (1973) A first course in factor analysis. Academic Press, New York

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16(3):297–334

Das SS, Tiwari AK (2021) Understanding international and domestic travel intention of Indian travellers during COVID-19 using a Bayesian approach. Tour Recreat Res 46(2):228–244

Deng L, Yang M, Marcoulides KM (2018) Structural equation modeling with many variables: a systematic review of issues and developments. Front Psychol 9:1–14

Dunn R, Hattie J, Bowles T (2018) Using the theory of planned behavior to explore teachers’ intentions to engage in ongoing teacher professional learning. Stud Educ Eval 59:288–294

Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C (2007) The benefits of facebook “friends:” social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J Comput-Mediat Commun 12(4):1143–1168

Fan X, Lu J, Qiu M, Xiao X (2022) Changes in travel behaviors and intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery period: a case study of china. J Outd Recr Tour 41:100522

Field A (2005) Factor analysis using SPSS. 63–71

Fielding KS, McDonald R, Louis WR (2008) Theory of planned behaviour, identity and intentions to engage in environmental activism. J Environ Psychol 28(4):318–326

Financial Express (2022) Coronavirus omicron Feb 26 highlights: third wave recedes in India! Delhi govt lifts all Covid restrictions as situation improves", [online], available at: https://www.financialexpress.com/lifestyle/health/coronavirus-omicron-live-news-february-26-live-covid-updates-omicron-latest-news-coronavirus-new-variants-coronavirus-blog-covid-vaccine-live-news-covid-blog-today-covid-live-news-today-latest-news-on/2444304/ (accessed 27 December 2022)

Finstad K (2010) Response interpolation and scale sensitivity: evidence against 5-point scales. J Usability Stud 5(3):104–110

Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley, MA

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50

Fuster JIA (2021) Rural tourism as a response to COVID-19. Caixabank Research. https://www.caixabankresearch.com/en/sector-analysis/tourism/rural-tourism-response-covid-19

Garay L, Font X, Corrons A (2019) Sustainability-oriented innovation in tourism: an analysis based on the decomposed theory of planned behaviour. J Travel Res 58(4):622–636

Gorsuch RL (1983) Factor analysis, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale

Greffe X (1994) Is rural tourism a lever for economic and social development? J Sustain Tour 2(1–2):22–40

Gretzel U, Yoo K-H (2017) Social media in hospitality and tourism. In: Dixit S (ed) Routledge handbook of consumer behaviour in hospitality and tourism. Routledge, New York, pp 339–346

Guo S, Lee CK (2007) Statistical power of SEM in social work research: challenges and strategies. In: Eleventh annual conference of the society of social work research. San Francisco

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson R (2014) Multivariate data analysis. Pearson New International Edition, London

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham R (2006) Multivariate Data Analysis, Uppersaddle River

Hair JF Jr, Hult GTM, Ringle C, Sarstedt M (2016) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications, Newbury Park

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Mena JA (2012) An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J Acad Mark Sci 40:414–433

Hair JF Jr, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC (1998) Multivariate data analysis. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey

Hamid AHA, Mohamad MR (2019) Validating theory of planned behavior with formative affective attitude to understand tourist revisit intention. Int J Trend Scient Res Devel 4(2):594–598

Hamid MA, Isa SM (2015) The theory of planned behavior on sustainable tourism. J Appl Environ Biol Sci 5(6S):84–88

Hamid S, Azhar M (2021) Influence of theory of planned behavior and perceived risk on tourist behavioral intention post-COVID-19. J Tour 22(2):15–25

Han H (2015) Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour Manage 47:164–177

Han H, Kim Y (2010) An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int J Hosp Manag 29(4):659–668

Han H, Al-Ansi A, Chua B, Tariq B, Radic A, Park S (2020) The post-coronavirus world in the international tourism industry: application of the theory of planned behavior to safer destination choices in the case of US outbound tourism. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(18):6485

Han H, Hsu LTJ, Sheu C (2010) Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour Manage 31(3):325–334

Hasan MK, Abdullah SK, Lew TY, Islam MF (2019) The antecedents of tourist attitudes to revisit and revisit intentions for coastal tourism. Int J Cult, Tour Hospit Res 3(2):218–234

Hasan MK, Ismail AR, Islam MDF (2017) Tourist risk perceptions and revisit intention: a critical review of literature. Cogt Bus Manag 4(1):1412874

Hennig-Thurau T, Gwinner KP, Walsh G, Gremler DD (2004) Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: what motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet. J Interact Mark 18:38–52

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sinkovics RR (2009) The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In: Sinkovics RR, Ghauri PN (eds) New challenges to international marketing (Advances in international marketing), vol 20. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 277–319

Hindustan Times (2021) Tourism post-Covid-19: Ministry floats strategy to promote medical, wellness, rural, MICE tourism" available at https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/tourism-post-covid-19-ministry-floats-strategy-to-promote-medical-wellness-rural-mice-tourism-101624026590433.html (accessed 8 November 2022)

Honey M, Gilpin R (2009) Tourism in the developing world: Promoting Peace and reducing poverty. United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved 30 November 2022, from https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/tourism_developing_world_sr233_0.pdf

Hsu CHC, Huang S (2012) An extension of the theory of planned behavior model for tourists. J Hospit Tour Res 36(3):390–417

Hsu CH, Killion L, Brown G, Gross M, Huang S (2008) Tourism marketing: An Asia-Pacific perspective. Wiley, Hoboken

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6(1):1–55

Huete-Alcocer N (2017) A literature review of word of mouth and electronic word of mouth: implications for consumer behavior. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.012564

Hussein HM, Salam EM, Gaber HR (2020) Investigating the factors that enhance tourists’ intention to revisit touristic cities. A case study on Luxor and Aswan in Egypt. Int J Afr Asian Stud 69:24–36

Indian Companies (2021) Top 10 travel companies in India 2022. [online], available at: https://indiancompanies.in/top-travel-companies-india/ (accessed on 20 December 2022)

Jager J, Putnick D, Bornstein M (2017) II More than just convenient: the scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monogr Soci Res Child Develop 82(2):13–30

Jalilvand MR, Samiei N (2012) The impact of electronic word of mouth on a tourism destination choice: testing the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Internet Res 22(5):591–612

Javed M, Tučková Z, Jibril AB (2020) The role of social media on tourists’ behavior: an empirical analysis of millennials from the Czech Republic. Sustainability 12(18):7735

Joo Y, Seok H, Nam Y (2020) The moderating effect of social media use on sustainable rural tourism: A theory of planned behavior model. Sustainability 12(10):4095

Jöreskog KG (1978) Structural analysis of covariance and correlation matrices. Psychometrika 43(4):443–477

Joshi A, Kale S, Chandel S, Pal DK (2015) Likert scale: explored and explained. Br J Appl Sci Technol 7(4):396

Juschten M, Jiricka-Pürrer A, Unbehaun W, Hössinger R (2019) The mountains are calling! An extended TPB model for understanding metropolitan residents’ intentions to visit nearby alpine destinations in summer. Tour Manage 75:293–306

Kaplan AM, Haenlein M (2010) Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus Horiz 53(1):59–68

Kaushik AK, Agrawal AK, Rahman Z (2015) Tourist behaviour towards self-service hotel technology adoption: Trust and subjective norm as key antecedents. Tour Manag Perspect 16:278–289

Khan NA, Azhar M, Rahman MN, Akhtar MJ (2022) Scale development and validation for usage of social networking sites during COVID-19. Technol Soc 70:102020

Kim S-H, Holland S, Han HS (2013) A structural model for examining how destination image, perceived value, and service quality affect destination loyalty: a case study of Orlando. Int J Tour Res 15(4):313–328

Kline RB (1998) Structural equation modeling. Guilford, New York

Kurfali M, Arifoğlu A, Tokdemir G, Paçin Y (2017) Adoption of e-government services in Turkey. Comput Hum Behav 66:168–178

Lam T, Hsu CHC (2004) Theory of planned behavior: potential travelers from China. J Hospit Tour Res 28(4):463–482

Lam T, Hsu CHC (2006) Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tour Manage 27(4):589–599

Lane B (1994) Sustainable rural tourism strategies: A tool for development and conservation. J Sustain Tour 2(1–2):102–111

Lane B (1994) What is rural tourism? J Sustain Tour 2(1–2):7–21

Lee CK, Song HJ, Bendle LJ, Kim MJ, Han H (2012) The impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions for 2009 H1N1 influenza on travel intentions: a model of goal-directed behavior. Tour Manage 33(1):89–99

Lim WM, Ahmad A, Rasul T, Parvez MO (2021) Challenging the mainstream assumption of social media influence on destination choice. Tour Recreat Res 46(1):137–140

Lin JC, Wu CS, Liu WY, Lee CC (2012) Behavioral intentions toward afforestation and carbon reduction by the Taiwanese public. Forest Policy Econ 4(1):119–126

Litvin SW, Goldsmith RE, Pan B (2008) Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tour Manage 29(3):458–468

Liu Y, Shi H, Li Y, Amin A (2021) Factors influencing Chinese residents’ post-pandemic outbound travel intentions: an extended theory of planned behavior model based on the perception of COVID-19. Tour Rev 76(4):871–891

Loureiro SMC (2014) The role of the rural tourism experience economy in place attachment and behavioral intentions. Int J Hosp Manag 40:1–9

MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM (1996) Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods 1(2):130–149

Madden T, Ellen P, Ajzen I (1992) A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 18(1):3–9

Mathieson K (1991) Predicting user intentions: comparing the technology acceptance model with the theory of planned behavior. Inf Syst Res 2(3):173–191

McDonald RP, Ho MHR (2002) Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods 7(1):64

Meng B, Choi K (2019) Tourists’ intention to use location-based services (LBS): converging the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and the elaboration likelihood model (ELM). Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 31(8):3097–3115

Miao Y (2015) The influence of electronic-WOM on tourists’ behavioral intention to choose a destination: a case of chinese tourists visiting thailand. AU-GSB e-J 8(1):13–31

Miles JN, Shevlin ME (1998) Multiple software review: drawing path diagrams. Struct Equ Modeling 5(1):95–103

Ministry of Tourism (June, 2021) National strategy & roadmap for development of rural tourism in India. Retrieved on 11 September 2022 from https://tourism.gov.in/sites/default/files/202106/Draft%20Strategy%20for%20Rural%20Tourism%20June%2012.pdf

Moorthy K, Salleh N, Jie A, Yi C, Wei L, Bing L, Ying Y (2020) Use of social media in planning domestic holidays: a study on Malaysian millennials. Millennial Asia 12(1):35–56

Moutinho L (1987) Consumer behavior in tourism. Eur J Mark 21(10):1–44

Narangajavana Y, Fiol LJC, Tena MÁM, Artola RMR, García JS (2017) The influence of social media in creating expectations. an empirical study for a tourist destination. Ann Tour Res 65:60–70

Nunnally JC (1978) Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill publication, New York

Pahrudin P, Chen C, Liu L (2021) A modified theory of planned behavioral: a case of tourist intention to visit a destination post pandemic Covid-19 in Indonesia. Heliyon 7(10):e08230

Park E, Choi BK, Lee TJ (2019) The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tour Manage 74:99–109

Prayogo RR, Kusumawardhani A (2017) Examining relationships of destination image, service quality, e-WOM, and revisit intention to Sabang Island, Indonesia. APMBA (Asia Pacific Manag Business Application) 5(2):89–102

Pujiastuti E, Nimran U, Suharyono S, Kusumawati A (2017) The antecedents of behavioral intention regarding rural tourism destination. Asia Pacific J Tour Res 22(11):1169–1181

Ramdan M, Rahardjo K, Abdillah Y (2017) The Impact of e-wom on destination image, attitude toward destination and travel Intention. Russian J Agricult Socio-Econ Sci 61(1):94–104

Rehman AU, Shoaib M, Javed M, Abbas Z, Nawal A, Zámečník R (2022) Understanding revisit intention towards religious attraction of Kartarpur temple: moderation analysis of religiosity. Sustainability 14(14):8646

Setia MS (2016) Methodology series module 3: cross-sectional studies. Indian J Dermatol 61(3):261–264

Shang Y, Mehmood K, Iftikhar Y, Aziz A, Tao X, Shi L (2021) Energizing intention to visit rural destinations: how social media disposition and social media use boost tourism through information publicity. Front Psychol 12:782461–782461

Söderlund M, Rosengren S (2007) Receiving word-of-mouth from the service customer: an emotion-based effectiveness assessment. J Retail Consum Serv 14(2):123–136

Soliman M (2019) Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict tourism destination revisit intention. Int J Hospit, Tour Administr 22(5):524–549

Sparks B (2007) Planning a wine tourism vacation? Factors that help to predict tourist behavioural intentions. Tour Manage 28(5):1180–1192

Sparks B, Pan GW (2009) Chinese outbound tourists: understanding their attitudes, constraints and use of information sources. Tour Manage 30(4):483–494

Sujood HS, Bano N (2021) Behavioral intention of traveling in the period of COVID-19: an application of the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and perceived risk. Int J Tour Cit 8(2):357–378

Sujood HS, Bano N (2021) Intention to visit eco-friendly destinations for tourism experiences: an extended theory of planned behaviour. J Tour, Sustain Well-being 9(4):343–364

Sultan MT, Sharmin F, Badulescu A, Stiubea E, Xue K (2020) Travelers’ responsible environmental behavior towards sustainable coastal tourism: an empirical investigation on social media user-generated content. Sustainability 13(1):56

Swan J (1981) Disconfirmation of expectations and satisfaction with a retail service. J Retail 57(3):49–66

Teng YM, Wu KS, Liu HH (2015) Integrating altruism and the theory of planned behavior to predict patronage intention of a green hotel. J Hospit Tour Res 39(3):299–315

Teo T, Tsai LT, Yang CC (2013) Applying structural equation modeling (SEM) in educational research: an introduction. In: Application of structural equation modeling in educational research and practice, pp. 1–21. Brill

The Hindu (2022) Coronavirus updates- February 25, 2022", [online], available at: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/coronavirus-live-updates-february-25-2022/article65083141.ece (accessed on 27 November 2022)

The World Bank. (2021) Rural population (% of total population) – India. Retrieved 12 October 2022, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=IN

Tsai FM, Bui TD (2021) Impact of word of mouth via social media on consumer intention to purchase cruise travel products. Marit Policy Manag 48(2):167–183

Uğur N, Akbıyık A (2020) Impacts of COVID-19 on global tourism industry: a cross-regional comparison. Tour Manag Perspect 36:100744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100744

van Zoonen W, Verhoeven J, Elving W (2014) Understanding work-related social media use: an extension of theory of planned behavior. Int J Manag Econ Soci Sci 3(4):164–183

Verma VK, Chandra B (2018) An application of theory of planned behavior to predict young Indian consumers’ green hotel visit intention. J Clean Prod 172:1152–1162

Wang D (2004) Tourist behaviour and repeat visitation to Hong Kong. Tour Geogr 6(1):99–118

Wang Q, Huang R (2021) The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on sustainable development goals – a survey. Environ Res 202:111637

Wang Q, Zhang F (2021) What does the China’s economic recovery after COVID-19 pandemic mean for the economic growth and energy consumption of other countries? J Clean Prod 295:126265

Wang Q, Wang L, Li R (2023) Trade protectionism jeopardizes carbon neutrality -decoupling and breakpoints roles of trade openness. Sustain Prod Consum 35:201–215

Wang Q, Wang X, Li R (2022) Does urbanization redefine the environmental Kuznets curve? An empirical analysis of 134 countries. Sustain Cities Soc 76:103382

Wheaton B, Muthen B, Alwin DF, Summers GF (1977) Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociol Methodol 8:84–136

Wolf EJ, Harrington KM, Clark SL, Miller MW (2013) Sample size requirements for structural equation models: an evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ Psychol Measur 73(6):913–934

Wyles KJ, White MP, Hattam C, Pahl S, King H, Austen M (2019) Are some natural environments more psychologically beneficial than others? The importance of type and quality on connectedness to nature and psychological restoration. Environ Behav 51(2):111–143

Xiang Z, Gretzel U (2010) Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour Manage 31(2):179–188

Yadav R, Pathak GS (2016) Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: extending the theory of planned behavior. J Clean Prod 135:732–739

Ying HL, Chung CM (2007) The effects of single-message single-source mixed word-of-mouth on product attitude and purchase intention. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 19(1):75–86

Yu M, Li Z, Yu Z, He J, Zhou J (2021) Communication related health crisis on social media: a case of COVID-19 outbreak. Curr Issue Tour 24(19):2699–2705

Yuzhanin S, Fisher D (2016) The efficacy of the theory of planned behavior for predicting intentions to choose a travel destination: a review. Tourism Review 71(2):135–147

Zhang Y, Yu X, Cheng J, Chen X, Liu T (2017) Recreational behavior and intention of tourists to rural scenic spots based on TPB and TSR Models. Geogr Res 36:1725–1741

Zhu H, Deng F (2020) How to influence rural tourism intention by risk knowledge during COVID-19 containment in China: mediating role of risk perception and attitude. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(10):3514

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors of this manuscript solemnly declare that no funding from any agencies was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA involved in conceptualization, data curation, writing—original draft, methodology, software and formal analysis. SN involved in resources, writing and reviewing and editing. S involved in resources, supervision and editing, SH involved in resources and editing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Azhar, M., Nafees, S., Sujood et al. Understanding post-pandemic travel intention toward rural destinations by expanding the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Futur Bus J 9, 36 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-023-00215-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-023-00215-2