Abstract

Background and aim

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is considered one of the most common cancers in the world and one of the principal causes of cancer-linked deaths. Therefore, identification of new biomarkers for diagnosis, especially early diagnosis of HCC, is very important. Pentraxin 3 (PTX3) is possibly involved in cancer development, and as regard to liver diseases, plasma PTX3 was implicated to be associated with HCC occurrence. Therefore, this study will determine the serum PTX3 levels in patients with cirrhosis and HCC and to assess the potential diagnostic value in HCC in Egyptian patients.

Results

Pentraxin 3 was significantly higher in HCC patients than in cirrhotic patients (p < 0.001); also, serum PTX3 was significantly correlated with number, size of focal lesions, the presence of portal vein thrombosis, and BCLC staging (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

The significant increased levels of serum pentraxin 3 in HCC may support its use as an early marker for HCC, either alone or in combination with serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), allowing early diagnosis and prompt intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is considered the sixth most common cancer disease in the world and as the second principal cause of cancer-linked deaths [1]. In HCC patients, prognostic factors are influential in the treatment plan selection of most patients with this type of cancer [2]. HCC is also the major cause of death among patients with cirrhosis [3].

However, the differentiation of small HCC from cirrhotic nodules is still difficult by imaging. Meanwhile, AFP, the most commonly used biomarker in HCC, is not specific for HCC, and elevated levels of AFP may be seen in both patients with HCC and chronic hepatitis without cancer [4,5,6].

In addition, AFP is potentially most suitable to detect advanced tumors because the concentrations are related to tumor size. Moreover, many HCC patients may exhibit no elevation of AFP levels, so AFP level cannot be utilized to detect HCC in these cases [5].

Therefore, identification of new biomarkers for diagnosis, especially early diagnosis, of HCC is an urgent need for clinical practice.

Pentraxin 3 (PTX3), also called tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene 14 (TSG-14), is a long pentraxin of the pentraxin superfamily [7], which is a class of ancient group of evolutionarily conserved and versatile proteins [8, 9]. Structurally, PTX3 has an unrelated N-terminal domain linked to a pentraxin-like C-terminal domain [10, 11].

PTX3 performs indispensable nonredundant roles in humoral innate immunity in microbial infections and acts as a connection between innate immunity, inflammation, tissue repair, and cancer [12,13,14,15].

Notably, PTX3 is possibly involved in cancer development. For example, PTX3 expression levels have been shown to be related to the prognosis in certain types of cancer such as breast cancer [16], gastric cancer [17], lung carcinoma [18], pancreatic carcinoma [19], and prostate cancer [20]. With regard to liver diseases, plasma PTX3 was found to be associated with HCC occurrence in chronic HCV infection [21]. Furthermore, PTX3 was shown to be able to promote HCC progression, and high PTX3 expression in tumor tissues was related to unfavorable prognosis in HCC patients [22]. Despite these studies, the potential role of circulating PTX3 in HCC remains to be further investigated. This study, therefore, will determine the serum PTX3 levels in patients with cirrhosis and HCC and assess the potential diagnostic value in HCC in Egyptian patients.

Patients and methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out on 100 patients who attended to Hepatocellular Carcinoma Unit of Tropical Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University, from May 2022 until March 2023.

Male or female patients older than 18 years with cirrhotic liver compensated or decompensated with and without hepatocellular carcinoma were included in the study, while patients aged < 18 years, patients with any chronic illness or inflammation, and patients with malignant disease other than liver cancer or unwilling to participate in our study were excluded from this study.

Enrolled patients were classified into the following:

-

Group I: It included 50 patients with liver cirrhosis without HCC.

-

Group II: It included 50 patients with liver cirrhosis and confirmed HCC.

All the patients were subjected to full history taking, complete clinical examination, measurement of serum PTX3 concentration (estimated by human pentraxin 3 (PTX3) ELISA kit) and expressed in ng/ml, complete blood picture, AFP, liver function tests, prothrombin time and activity and INR, urea and creatinine,abdominal ultrasound, and multislice triphasic CT (MSCT) of abdomen and pelvis in group II patients. Peripheral blood samples were collected from the patients’ antecubital vein in the prone position and placed into two serum tubes containing clot activator, one EDTA tube and one Na citrated tube between 8:00 and 10:00 am. The serum tubes were then centrifuged at 3000 g for 15 min. Serum samples for pentraxin 3 (PTX3) were stored at -20 degrees Celsius until they were tested.

On the same day of collection, KONELAB PRIME 60i was used to detect serum ALT, AST, albumin, total bilirubin, urea and creatinine) using reagents from Thermo Fisher Scientific Oy-Finland. AFP was measured using automated chemistry analyzer (Cobas 6000) using ROCHE Diagnostic kits. A complete blood count (CBC) was performed on an electronic automatic analyzer (ERMA Inc. Poland), Stago STA compact was used to measure PT, activity, and INR with kits from DIAGNOSTICA STAGO. Serum Pentraxin 3 (PTX3) was measured using the Sun Red Human PTX3 ELISA kit (Catalogue No. 201-12-1939). The kit measured the amount of human pentraxin 3 (PTX3) in samples using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) double-antibody sandwich method.

A written informed consent was signed by every patient, and a code number for each patient was used.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Faculty of Medicine Tanta University with approval code 35463/5/22.

Statistical analysis

Data were fed to the computer and analyzed using IBM SPSS software package version 20.0. (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Categorical data were represented as numbers and percentages. Chi-square test was applied to compare between two groups. Alternatively, Fisher exact or Monte Carlo correction test was applied when more than 20% of the cells have expected count less than 5. For continuous data, they were tested for normality by the Shapiro-Wilk. Quantitative data were expressed as range (minimum and maximum), mean, standard deviation, and median for normally distributed quantitative variables Student t-test was used to compare two groups. On the other hand, for not normally distributed quantitative variables, Mann-Whitney test was used to compare two groups. Significance of the obtained results was judged at the 5% level.

Results

This study recruited 100 CLD compensated or decompensated patients including 50 cirrhotic non-HCC patients (male/female 29/21; mean age, 59.5 ± 6.17 years) and 50 HCC patients (male/female, 30/20; mean age, 61.4 ± 5.69 years). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups as regards to male/female ratio and age, as shown in Table 1.

The cirrhotic group with HCC included 26 patients with child b,14 with child c, and 10 with child a, while the other group without HCC included 30 patients with child b,19 with child a, and 1 patient with child c.

There was no significant difference as regard HB level, WBCS, ALT, AST, total bilirubin, and INR between the two groups, while HCC patients had a significant lower platelets count than cirrhotic patients without HCC (P = 0.015) and a lower serum albumin level than in cirrhotic patients (p < 0.001), as shown in Table 1.

For kidney function tests, there was no significant difference in urea level between the two groups, while creatinine was statistically lower in HCC patients than cirrhotic patients without HCC (P = 0.026) as shown in Table 1.

As regard AFP, it was significantly higher in HCC patients than in cirrhotic patients without HCC (p < 0.001), as shown in Table 2.

The results showed also that pentraxin 3 was significantly higher in HCC patients than in cirrhotic patients (p < 0.001) as shown in Table 2. Serum PTX 3 was elevated in HCC patients with normal value of AFP (11 patients with AFP < 20 IU/ml) with median value 8.4 (2.1–15.4) ng/ml.

This study included 50 HCC patients; the number of focal lesions was single in 32 patients (64%) and multiple in 18 patients (36%). Size of focal lesions was < 5 cm in 20 patients (40%) and ≥ 5 cm in 30 patients (60%). Nineteen patients (38%) had portal vein thrombosis, as regard Barcelona staging, 3 patients (6%) were stage A, 10 patients (20%) were stage B, 7 patients (14%) were stage C, and 30 patients were stage D (60%), as shown in Table 3.

Both AFP and serum PTX3 were significantly correlated with the number of focal lesions with p-value (< 0.001) in both markers. AFP was elevated with increased size of focal lesion, but the results were not statistically significant, while serum PTX3 was significantly correlated with the size of focal lesion, p-value (0.458, < 0.001). AFP was also elevated in patients with portal vein thrombosis but not statistically significant, while serum PTX3 was significantly correlated with the presence of PVT, p-value (0.497, 0.013), respectively. AFP was not correlated with BCLC staging, while serum PTX 3 was significantly correlated with BCLC staging (p 0.292, 0.003), respectively, as shown in Table 3.

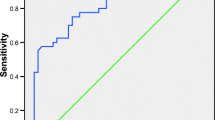

The performance of PTX3 for identifying HCC was assessed using ROC curve. Serum PTX3 cut-off value was ≥ 6.4 (ng/ml) which significantly differentiate HCC from cirrhotic patients without HCC with sensitivity 80% and specificity 74%. On the other hand, the cut-off value of AFP was ≥ 14 (IU/ml) with sensitivity which was 88%, and its specificity was 84%. The combination of PTX3 with AFP improved the performance of PTX3 or AFP alone with sensitivity 92% and specificity 76%, as shown in Table 4 and Fig. 1.

Discussion

Hepatocellular carcinoma is one of the world’s most frequent malignancies, and the prognosis for HCC is poor in many individuals, so it continues to be one of the most lethal cancers, with more than two-thirds of patients diagnosed at late stages of illness [23].

Finding the most useful biomarkers to be added to or replace AFP in HCC diagnosis, and even an appropriate tool for evaluating tumor spread and patient prognosis, is crucial. These markers could in fact guide clinical decision-making regarding HCC treatment. So the goal of our study was to determine the serum PTX3 levels in patients with cirrhosis and HCC and assess the potential diagnostic value in HCC in Egyptian patients.

As a member of the long pentraxin subfamily, PTX-3 is crucial in controlling angiogenesis, inflammation, innate immunity, and tissue remodelling. PTX-3 expression can be induced in a variety of cell types, including neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, myeloid dendritic cells, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells, via increased production of inflammatory biomarkers and activation of multiple biological processes. PTX-3 has multiple roles in oncogenesis since it has both pro- and anti-tumor effects [17].

The role of PTX-3 in cancer progression was discussed in many types of cancer [24, 25].

The mechanisms of PTX3 in the development of tumors and carcinogenesis are not fully understood. Chronic inflammation plays a significant role in the development and progression of cancer. And it is a crucial component of the tumor microenvironment in HCC, and it has a significant impact on the growth and progression of the disease [26].

There is a suggestion that PTX3 has a role in the pathophysiology of fibrosis and inflammation in the liver [27].

Humoral immunity, among immunologic processes, is important for the emergence and evolution of HCC [28]. The correlation between PTX3 and HCC may possibly be influenced by its role in the immune response. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-1 can induce PTX3 expression [29].

Although PTX3 is thought not to be produced by hepatocytes [30], it has been demonstrated to be able to promote HCC cell proliferation and induce the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a biologic process closely linked to tumor cell invasion and metastasis. This provides another explanation for the role of PTX 3 in HCC [31].

Our study showed significant increase in PTX-3 level in HCC patients compared to cirrhotic This was consistent with a study by Deng H. et al. [32] that studied serum pentraxin 3 as a biomarker of hepatocellular carcinoma and showed serum PTX3 as a new indicator for HCC diagnosis and showed that the performance of PTX3 for differentiating HCC from chronic HBV infection was superior to AFP. Also, Han Q. et al. [33] demonstrated that increased serum pentraxin 3 levels are associated with poor prognosis of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma.

More other studies confirmed the potential role of PTX3 as a biomarker in evaluating the disease severity and prognosis of cirrhosis [34] and HCC [20, 35].

Our results showed that PTX-3 serum levels were positively correlated with number, size of focal lesions, the presence of portal vein thrombosis, and BCLC staging which was in agreement with Song et al. [31] who found higher pentraxin 3 expressions in more aggressive HCCs.

We also found that serum PTX 3 was elevated in 11 patients with normal values of AFP. This suggests its role in early diagnosis of HCC in AFP-negative patients. According to Deng H. et al., PTX3 performed better than AFP in terms of diagnostic performance and was accurately discriminative of AFP-negative and early-stage HCC. According to these results, PTX3 may be employed as an additional biomarker for AFP-negative or low AFP HCC as well as a more sensitive biomarker for HCC, particularly early HCC [32]. Also, Han Q. et al. demonstrated that serum PTX3 levels could be used as a prognostic biomarker for HBV-related HCC, especially AFP-negative HCC [33].

It is important to note that our findings indicated that the combination of PTX3 and AFP with AUC 0.935 had a greater diagnostic impact (p < 0.001). This suggests that the two biomarkers (AFP and PTX-3) together can provide a higher scoring for the HCC diagnostic approach.

Conclusions

The significantly increased levels of serum pentraxin 3 in HCC may support its use as an early marker for HCC, either alone or in combination with serum AFP, allowing early diagnosis and prompt intervention. Additionally, the significant high values of serum pentraxin 3 in patients with larger tumor sizes, multiple focal lesions, portal vein thrombosis, and BCLC staging could imply their use as a marker of HCC aggressiveness.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- PTX3:

-

Pentraxin 3

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- HB:

-

Hemoglobin

- WBCs:

-

White blood cells

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminases

- AST:

-

Aspartate transaminases

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- CR:

-

Creatinine

- MIN:

-

Minimum

- MAX:

-

Maximum

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- BCLC:

-

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- HBV infection:

-

Hepatitis B virus infection

References

Rawla P, Sunkara T, Muralidharan P, Raj JP (2018) Update in global trends and aetiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 22(3):141–150

Goyal H, Hu ZD (2017) Prognostic value of red blood cell distribution width in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Transl Med 5(13):271

Sangiovanni A, Ninno E, Fasani P, Fazio C, Ronchi G, Romeo R et al (2004) Increased survival of cirrhotic patients with a hepatocellular carcinoma detected during surveillance. Gastroenterology 126(4):1005–1014

Forner A, Bruix J (2012) Biomarkers for early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet Oncol 13(8):750–751

Luo P, Wu S, Yu Y, Ming X, Li S, Zuo X, Tu J (2020) Current status and perspective biomarkers in AFP negative HCC: towards screening for and diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma at an earlier stage. Pathol Oncol Res 26(2):599–603

Bottazzi B, Bastone A, Doni A, Garlanda C, Valentino S, Deban L et al (2006) The long pentraxin PTX3 as a link among innate immunity, inflammation, and female fertility. J Leukoc Biol 79:909–912

Bottazzi B, Doni A, Garlanda C, Mantovani A (2010) An integrated view of humoral innate immunity: pentraxins as a paradigm. Annu Rev Immunol 28:157–183

Inforzato A, Doni A, Barajon I, Leone R, Garlanda C, Bottazzi B, Mantovani A (2013) PTX3 as a paradigm for the interaction of pentraxins with the complement system. Semin Immunol 25(1):79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smim.2013.05.002

Garlanda C, Bottazzi B, Bastone A, Mantovani A (2005) Pentraxins at the crossroads between innate immunity, inflammation, matrix deposition, and female fertility. Annu Rev Immunol 23:337–366

Doni A, Michela M, Bottazzi B, Peri G, Valentino S, Polentarutti N et al (2006) Regulation of PTX3, a key component of humoral innate immunity in human dendritic cells: stimulation by IL-10 and inhibition by IFN-gamma. J Leukoc Biol 79(4):797–802

Garlanda C, Bottazzi B, Magrini E, Inforzato A, Mantovani A (2018) PTX3, a humoral pattern recognition molecule, in innate immunity, tissue repair, and cancer. Physiol Rev 98(2):623–639

Doni A, Stravalaci M, Inforzato A, Magrini E, Mantovani A, Garlanda C (2019) Bottazzi B The long pentraxin PTX3 as a link between innate immunity, tissue remodeling, and cancer. Frontiers Immunol 10:712

Bonita E, Mantovani A, Garlanda C (2015) PTX3 acts as an extrinsic oncosuppressor. Oncotarget 6(32):32309–32310

Jaillon S, Moalli F, Ragnarsdottir B, Bonavita E, Puthia M, Riva F et al (2014) The humoral pattern recognition molecule PTX3 is a key component of innate immunity against urinary tract infection. Immunity 40(4):621–32

Choi B, Lee E, Song D, Yoon S, Chung Y, Jang Y et al (2014) Elevated pentraxin 3 in bone metastatic breast cancer is correlated with osteolytic function. Oncotarget 5(2):481–492

Choi B, Lee E, Park Y, Kim S, Kim E, Song Y et al (2015) Pentraxin-3 silencing suppresses gastric cancer-related inflammation by inhibiting chemotactic migration of macrophages. Anticancer Res 35(5):2663–2668

Diamandis EP, Goodglick L, Planque C, Thornquist MD (2011) Pentraxin-3 is a novel biomarker of lung carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 17(8):2395–2399

Kondo S, Ueno H, Hosoi H, Hashimoto J, Morizane C, Koizumi F et al (2013) Clinical impact of pentraxin family expression on prognosis of pancreatic carcinoma. Br J Cancer 109(3):739–746

Stallone G, Cormio L, Netti G, Infante B, Selvaggio O, Fino G et al (2014) Pentraxin 3: a novel biomarker for predicting progression from prostatic inflammation to prostate cancer. Can Res 74(16):4230–4238

Carmo F, Aroucha A, Vasconcelos L, Pereira L, Moura P, Cavalcanti M (2016) Genetic variation in PTX3 and plasma levels associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with HCV. J Viral Hepatitis 23(2):116–122

Song T, Wang C, Guo C, Liu Q, Zheng X (2018) Pentraxin 3 overexpression accelerated tumor metastasis and indicated poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma via driving epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cancer 9(15):26502658

Zhu Q, Li N, Zeng X, Han Q, Li F, Yang C et al (2015) Hepatocellular carcinoma in a large medical center of China over a 10-year period: evolving therapeutic option and improving survival. Oncotarget 6(6):4440–4450

Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F (2008) Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 454(7203):436–444

Infante M, Allavena P, Garlanda C, Nebuloni M, Morenghi E, Rahal D et al (2016) Prognostic and diagnostic potential of local and circulating levels of pentraxin 3 in lung cancer patients. Int J Cancer 138(4):983–991

Stallone G, Cormio L, Netti G, Infante B, Selvaggio O, Fino G et al (2014) Pentraxin3: a novel biomarker for predicting progression from prostatic inflammation to prostate cancer. Cancer Res 74.16:4230–4238

Bishayee A (2014) The role of inflammation and liver cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 816:401–435

Bogdan M, Meca A-D, Turcu-Stiolica A, Oancea CN et al (2022) lnsights into the relationship between Pentraxin-3 and cancer. Int J Mol Sci 23(23):15302

Zhang S, Liu Z, Wu D, Chen L, Xie L (2020) Single-cell RNA-seq analysis reveals microenvironmental infiltration of plasma cells and hepatocytic prognostic markers in HCC with cirrhosis. Front Oncol 10:596318

Lee GW, Lee TH, Vilcek J (1993) TSG-14, a tumor necrosis factor- and IL-1-inducible protein, is a novel member of the pentaxin family of acute phase proteins. J Immunol 150(5):1804–1812

Savchenko A et al (2008) Expression of pentraxin 3 (PTX3) in human atherosclerotic lesions. J Pathol 215(1):48–55

Song T, Wang C, Guo C, Liu Q, Zheng X (2018) Pentraxin 3 overexpression accelerated tumor metastasis and indicated poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma via driving epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cancer 9(15):2650–2658

Deng H, Fan X, Wang X, Zeng L, Zhang K, Zhang X et al (2020) Serum pentraxin 3 as a biomarker of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Sci Rep 10:20276. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77332-3

HanQ DH, Fan X, WangX ZX, Zhang K (2021) Increased serum pentraxin 3 levels are associated with poor prognosis of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 8:1367–1373

Schiavon J, Pereira J, Silva T, Bansho E, Morato E, Pinheiro J et al (2017) Circulating levels of pentraxin-3 (PTX3) in patients with liver cirrhosis. Ann Hepatol 16(5):780–787

Cabiati M, Gaggini M, De Simone P, Del Ry S (2021) Do pentraxin 3 and neural pentraxin 2 have different facet function in hepatocellular carcinoma? Clin Exp Med 21(4):555–562

Acknowledgements

No

Funding

No

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made contributions to collection and interpretation of the data, drafting of the paper and the final approval of the version to be published. And made substantial contributions to concept and design of the study, revised the manuscript, and gave their approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Helal, E.M., Shoeib, S.M. & Mansour, S.M. The potential diagnostic value of serum pentraxin-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma in Egyptian patients. Egypt Liver Journal 14, 37 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-024-00344-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-024-00344-5