Abstract

Background

Colonic perforation usually presents with classical signs of peritonitis. However, isolated retroperitoneal colonic perforation can present with varied clinical signs and symptoms and pose diagnostic challenges. Pneumo-mediastinum and abdominal subcutaneous emphysema can be one of the presenting signs of colonic perforation.

Case report

A 33-year-old male presented with abdominal distension and extensive subcutaneous emphysema over the abdomen, pneumo-mediastinum, and pneumo-scrotum secondary to sigmoid colon perforation from a foreign body. The patient did not have classical signs of peritonitis.

Conclusion

Being vigilant about the potential of colonic perforation is crucial when observing a significantly increasing subcutaneous emphysema across different parts of the body. Attending clinicians should always keep intraabdominal pathology in mind when a direct cause for these symptoms cannot be found and the patient’s symptoms become progressive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Subcutaneous emphysema is a medical condition arising from the entrapment of air in the subcutaneous tissue, and it is often linked to air-containing organs. The chest wall is the most frequent location where subcutaneous emphysema occurs due to lung pathology. In instances where subcutaneous air is present in atypical locations, it has the potential to shift the focus of a clinician away from the true source. Such occurrences require careful consideration and attention to avoid misdiagnosis or mistreatment. Massive subcutaneous emphysema over the abdomen, scrotum, and pneumo-mediastinum due to intraabdominal primary pathology is a rare entity [1]. With subtle abdominal signs and without classical signs of peritonitis, it is difficult to identify intestinal perforation as a cause of subcutaneous emphysema.

Only a small number of cases involving colonic diverticular perforation and subcutaneous emphysema have been reported [2, 3]. Here, we present a case of foreign body perforation of the sigmoid colon which presented in a similar fashion.

Case report

A 33-year-old male presented with pain abdomen and mild abdominal distension for 6 days and obstipation for 4 days. The patient is a known case of Arnold-Chiari malformation type 1 with residual dystonia.

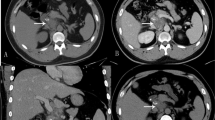

On examination, the abdomen was soft, with mild distension and minimal diffuse tenderness without guarding or rigidity. Subcutaneous emphysema was present over the whole of the abdomen, chest, neck, and scrotum. Chest x-ray and x-ray of the erect abdomen were done; it showed pneumo-mediastinum without pneumothorax. CECT chest with abdomen was done to further evaluate the patient and to identify the cause. In the pelvic area, a foreign object was detected during the CECT. It had penetrated the intestinal wall and pierced the lateral abdominal wall on the right side, leading to extensive subcutaneous emphysema, and pneumo-mediastinum (Fig. 1).

The patient was taken for an emergency laparotomy. Intraoperatively, a pen was visualized in the sigmoid colon, perforating it at the mesenteric border and piercing the right lateral abdominal wall just above ASIS (Fig. 2). The pen was removed, and a thorough wash was given. The rest of the abdominal viscera were inspected. The mesentery and omentum revealed extensive air bubbles. Edges of sigmoid perforation were freshened. Primary closure of the perforation was done, and proximal diversion loop colostomy was created. Debridement of the lateral abdominal wall necrotic tissue was done, and abdominal drain was kept. The postoperative period was uneventful.

Discussion

The mechanism of extraluminal air into the subcutaneous plane and mediastinum secondary to colonic perforation is due to the potential anatomical communication between the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, and subcutaneous plane [4].

In this case, two possible mechanisms of air entry into the retroperitoneum are possible.

-

1.

Colonic perforation into colonic mesentery causes air to enter into the retroperitoneum. Left pararenal retroperitoneal space communicates into the mediastinum, which is a possible cause for pneumo-mediastinum without pneumothorax [5, 6].

-

2.

The other possible mechanism is the direct puncture of the foreign body into the lateral abdominal wall, through which air would have escaped into subcutaneous and retroperitoneal spaces.

Following perforation of the colon, symptoms occur depending on the type of perforation.

-

Intraperitoneal perforations display typical signs of peritonitis. Early detection allows for prompt management.

-

Extraperitoneal perforations into mesentery can present with subcutaneous emphysema, pneumo-mediastinum, and pneumothorax without any abdominal signs.

-

Combined intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal can present with combined signs with vague abdominal symptoms.

Diagnosis in extraperitoneal and combined intra- and extraperitoneal perforation can pose challenges because of varied presentation, and the possibility of these types of injury should be kept in mind. CT scan is a useful investigation in such cases. CT scans possess the capability to accurately identify perforation locations, gas, and fluid within the body, making it easier to differentiate between air and fat tissues.

Management is individualized depending on the cases. A simple percutaneous drainage is often insufficient, and emergency surgery is usually necessary, particularly in cases with peritoneal signs, and rapidly expanding emphysema. It is important to distinguish the presence of free air under the skin from infection caused by gas-forming organisms. The latter is a serious condition, which can further deteriorate the patient’s overall health. Any tissue with suspicion of such added infection warrants a thorough debridement. In our case, we performed a thorough removal of damaged tissue from the lateral abdominal wall. This usually removes the additional foci of sepsis and helps in early recovery of the patient.

Conclusion

The accumulation of air in tissue planes on imaging suggests that further investigation is required to identify the underlying cause. It is vital to take into account the possibility of intestinal perforation when an individual is exhibiting mild or ambiguous abdominal symptoms. Being vigilant about the potential of colonic perforation is crucial when observing a significantly increasing subcutaneous emphysema across different parts of the body. This heightened awareness can effectively prevent any delay in diagnosis and minimize the possibility of any adverse effects on the patient.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- ASIS:

-

Anterior superior iliac spine

- CECT:

-

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Marwan K, Farmer KC, Varley C, Chapple KS (2007) Pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum, pneumoretroperitoneum and subcutaneous emphysema following diagnostic colonoscopy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 89(5):W20–W21

Kassir R, Abboud K, Dubois J et al (2014) Perforated diverticulitis of the sigmoid colon causing a subcutaneous emphysema. Int J Surg Case Rep 5(12):1190–1192

Fosi S, Giuricin V, Girardi V et al (2014) Subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, pneumoretroperitoneum, and pneumoscrotum: unusual complications of acute perforated diverticulitis. Case Reports in Radiology 2014:5

Ball CG, Kirkpatrick AW, Mackenzie S et al (2006) Tension pneumothorax secondary to colonic perforation during diagnostic colonoscopy: report of a case. Surg Today 36:478–480

Kipple JC (2010) Bilateral tension pneumothoraces and subcutaneous emphysema following colonoscopic polypectomy: a case report and discussion of anesthesia considerations. AANA J 78:462–467

Kim BH, Yoon SJ, Lee JY, Moon JE, Chung IS (2014) Subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, pneumoretroperitoneum, and pneumoperitoneum secondary to colonic perforation during colonoscopy. Case Reports in Radiology. 2014

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KH, a supervisor, did the literature review, and conceptualized and drafted the initial manuscript. KSR was a major contributor to writing the manuscript. AR did the literature review and critically reviewed the manuscript. PKS gathered the clinical information and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was requested from the office of the Institutional Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, NIMS University, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. Taken.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haldeniya, K., Krishna, S.R., Raghavendra, A. et al. Pneumo-mediastinum, pneumoperitoneum, and pneumo-scrotum with extensive increasing subcutaneous emphysema: a rare presentation of colonic perforation. Egypt Liver Journal 13, 68 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-023-00301-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-023-00301-8