Abstract

Background

Therapeutic interventions for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) particularly in patients with advanced liver disease may lead to more aggravation of clinical and biochemical parameters of liver functions. We aimed to assess the utilization of easily applied variables which evaluate residual hepatic reserve to predict liability for complications and hepatic decompensation in cirrhotic patients with ablated HCC particularly when these patients were exposed to specific medical treatment such as DAAs and systemic therapy for HCC such as sorafenib.

This study included 3 groups with HCC. Group 1: patients with ablated HCC and Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) class A, who received Sofosbuvir (SOF)-based treatment (n = 250), group 2: HCC patients CTP (A), managed with sorafenib after transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) (n = 250) and group 3 as a control group of non-cirrhotic patients (n = 176). Evaluation for all patients was done by routine laboratory investigations including liver and kidney functions, complete blood count, platelet indices and plasma ammonia, upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy and estimation of liver volume by ultrasound and liver stiffness (LS) by Fibroscan.

Results

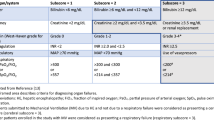

Unfavorable outcome and increased incidence of complications during DAAs were independently associated with severity of thrombocytopenia (p = 0.001) at a cut-off 78,000/μl, LS > 20 kPa (p = 0.001), liver volume < 500 ml (p = 0.002), and gamma globulin levels > 4 gm/dl (p = 0.004).

In the sorafenib group, unfavorable outcome and complications were independently associated with PDW/MPV ratio > 2.74 (p = 0.001), level of ammonia > 87 μg/dl (p = 0.001), LS > 25 kPa (p = 0.001), and liver volume < 490 ml (p = 0.001).

Conclusion

Non-invasive parameters of residual hepatic reserve are promising tools to guide therapy and avoid further complications in patients with liver cirrhosis and ablated HCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the 6th most common human malignant tumor and is the 4th most common cause of cancer-related mortality [1]. In the past few decades, multiple therapeutic options became available for patients with HCC according to their liver function status, performance score, tumor size, and aggressiveness.

These therapeutic modalities range from surgical treatment as liver transplantation and liver resection, locoregional interventions as RFA, microwave ablation and TACE, and pharmacological treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors as sorafenib for advanced non-operable compensated cases [2]

Documented ablation of HCC is an essential pre-requisite for implementation of direct-acting antiviral (DAAs) drugs. The most common devastating sequel of HCC medical treatment and DAAs therapy is liver decompensation, such as ascites, hyperbilirubinemia, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, HCC recurrence, and cardiac toxicity particularly in cirrhotic patients with HCC [3, 4].

Liver cirrhosis in the compensated stage should be offered the treatment with close follow-up as decompensation may occur with its grave complications mainly variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and/or hepatorenal syndrome [5].

Evaluation of the residual liver reserve by static and dynamic tests before any therapeutic medical, interventional, or surgical modality is an important predictor of post-treatment or procedural hepatic decompensation in high-risk patients. Hepatic reserve is the measure of quantity and quality (function) of the remaining liver cells and their capability to tolerate the initial phase after any therapeutic procedure without decompensation or failure of the synthetic function [6].

The static tests such as model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) scores quantify liver functions to assess the extent and severity of liver cirrhosis, and predict the prognosis and mortality before TIPS or liver transplantation [7].

The dynamic liver function tests evaluate the ability of the liver to metabolize or to eliminate substances. They include clearance tests as indocyanine green, caffeine and bromsulphalein clearance tests; elimination tests such as galactose removal capacity, and formation of metabolites such as mono-ethyl glycine xylidide from lignocaine. However, these tests are expensive and need specialized centers [8]

The functional hepatic reserve can be evaluated by liver volume; it can be detected by complex procedures as single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and magnetic resonance imaging [9,10,11] or simply by bedside abdominal ultrasound with a cut-off value 495 ml that can predict possible hepatic complications [12].

The current study aimed to assess the utility of simple variables that predict the residual hepatic reserve and complications mainly hepatic decompensation in cirrhotic patients with ablated HCC, as vascular hepatic decompensation (bleeding esophageal varices) or parenchymatous decompensation (ascites, jaundice) particularly when these patients were exposed to specific medical treatment such as DAAs and systemic therapy for HCC such as sorafenib, in addition evaluation of the impact of residual hepatic reserve on the incidence of SVR and tumor recurrence after ablative treatment for HCC.

Methods

Patient selection

This prospective study was conducted in Gastroenterology &Hepatology Unit, Internal Medicine Department-Zagazig University Hospitals-Egypt from January 2016 till January 2020. The protocol of this study was revised and approved by the institutional review board (IRB) and ethical committees of Zagazig Faculty of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained from every patient prior to enrollment in the study.

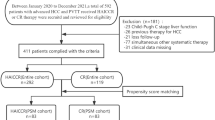

The study had enrolled 676 patients who were classified into two main groups as described in flowchart of Fig. 1. Groups 1 and 2 which included 500 patients with compensated liver cirrhosis and HCC on top of chronic HCV.

Group 1(n = 250), which included compensated cirrhosis patients (CTP-class A) with inoperable HCC who reported successful HCC loco-regional ablation at least 6 months prior starting treatment for chronic HCV using Sofosbuvir 400 mg, Daclatasvir 60 mg and weight based ribavirin.

Group 2 (n = 250): which had enrolled patients with (CTP-class A) and inoperable HCC who were managed with TACE followed by sorafenib.

Patients were included if they had chronic HCV diagnosed by HCV-RNA using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and had liver cirrhosis confirmed by abdominal ultrasound (nodular surface, rounded edge, coarse echopattern, prominent caudate lobe, and hypoechoic nodules in liver parenchyma), Fibroscan > 12.5 kPa denoting F4 and liver cirrhosis, Child-Pugh score class A, HCC was diagnosed according to guidelines of the European Association for the Study of Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) and patient performance status (PS) scale = 0–1 according to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG).

Patients were excluded if they had current or previous parenchymatous hepatic decompensation (ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, acute liver failure etc.), previous liver transplantation, PS > 1, and prior virological relapse after SOF-based therapy or co-infection with HBV or HIV.

- Group 3 (control group): chronic HCV patients with HCC and without cirrhosis (Fibroscan reading < 12.5 kPa) matched for age and gender (n = 176).

It included 130 patients who received DAAs for chronic HCV after documented ablation of HCC and 46 patients with advanced HCC who received sorafenib after TACE or radiofrequency ablation.

They were compared in terms of the incidence of liver-related adverse effects following the planned treatment.

Patients’ evaluation

All patients enrolled in the study were subjected to careful history taking and clinical examination for signs of liver cirrhosis and decompensation.

Laboratory investigations

They included complete blood count (CBC), platelet indices as PDW, MPV, liver and kidney function tests, prothrombin time and concentration, and international normalized ratio (INR) in addition to serum level of alpha fetoprotein (AFP) and calculation of CTP and MELD scores.

Real-time quantitative PCR for HCV-RNA (detection limit 15 IU/ml; Roche Diagnostic Systems) was performed before treatment with DAAs, 4 weeks after the start of treatment, at the end of therapy, and 6 months after treatment termination to confirm sustained virological response (SVR).

Plasma level of ammonia (n: 10–60 μg/dl)

A venous blood sample was collected after 6 h of fasting and abstinence from smoking for at least 8 hours, drugs as diuretics, antibiotics, uncontrolled hyperglycemia, or hypokalemia. The samples were put in EDTA containing sterile tubes, analysis was performed by the enzymatic method.

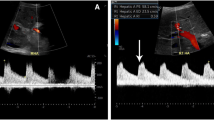

Abdominal ultrasound examination

It was performed with a single well experienced physician using an ultrasound device (Sonoscape A6T). Portal hypertension parameters such as portal vein diameter, splenic bipolar diameter and splenic vein diameter were evaluated. Patients with ascites, new appearance or recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma had been excluded. Bed-side ultrasound estimation of the liver volume using the standard ellipsoid formula (max. length × max. width × max. depth × 0.523) (Fig. 2) as a predictor of hepatic functional cellular reserve, normal liver volume for adults is nearly 1260 up to 1600 ml [13].

Liver stiffness (LS) evaluation by Fibroscan

The assessment was performed by a well-trained hepatologist using Fibroscan® device (EchoSens, Paris, France) with a range of 2.5 to 75 kPa. The patient was fasting and evaluated in the supine position, with the right arm maximally abducted. The median value of 10 measurements was calculated with a success rate of ≥ 60% and an interquartile range of < 30%. LS> 12.5 kPa indicated liver cirrhosis. Additionally, the risk of liver-related adverse events after hepatic therapeutic interventions is markedly increased with LS > 12.5 kPa; for example, the risk of esophageal varices is significantly increased with LS > 25 kPa [14].

According to Fibroscan measurements, the patients of groups 1 and 2 were classified into a subgroup with LS (12.5–25 kPa), and a subgroup with LS (> 25 kPa) as shown in (Table 2).

Upper GI endoscopy

It was performed in high-risk patients denoted by ultrasonographic features of portal hypertension, platelet count< 100 × 103/dl and Fibroscan > 25 kPa to exclude esophageal varices which were treated with band ligation before the planned therapy with DAAs or sorafenib.

Statistical methods

Results were analyzed using the SPSS version 20 (Chicago, USA). Continuous variables were defined as mean ± standard deviations. Chi-square test, Student’s t test, and variance analysis were used appropriately.

Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r) was performed for ordinal variables and Pearson correlation for continuous variables. Logistic regression analysis was performed by forward selection to identify variables independently associated with complications and outcome. All variables with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

A receiver operating curve (ROC) was performed to test the diagnostic efficacy of the high risk variables. The performance of the cut-off value was judged by calculation of Youden’s J value; values near 1 indicated good performance (J = sensitivity + specificity – 1).

Results

The study had included 676 patients; 500 patients with CTP (class A) cirrhosis and HCC who had been managed by medical therapeutic interventions as DAAs or sorafenib therapy in eligible subjects and a control non-cirrhotic group (n = 176).

The baseline demographic data, laboratory and endosonographic results are shown in (Table 1). The study enrolled 378 (75.6%) males and 122 (24.4%) female patients with mean age 44.3 ± 3.6 years. Mean liver volume of the study patients was 575.57 ± 84.3 ml and mean LS by Fibroscan was 24.07 ± 5.5 kPa.

Upper GI endoscopy had revealed grade I–II EVs in 112 patients (22.4%), grade III–IV in 86 patients (17.2%), fundal varices in 45 patients (9%). All were managed with endoscopic band ligation or amacrylate injection respectively before therapeutic intervention implementation.

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, patients in the DAAs-treated and sorafenib-treated groups were further sub-classified into two subgroups according to Fibroscan value and compared with the control group. There was a significant difference in serum gamma globulin, platelet count, and liver volume, plasma ammonia and incidence of complications among the 3 groups (p = 0.001).

Complications had occurred in 252 patients (50.4%), they were more frequent in the study groups which higher LS > 25 kPa and reduced liver volume as shown in Tables 2 and 3 when compared to the control group.

Virological relapse was detected in 64 patients which was significantly higher in study groups with higher LS when compared to the non-cirrhotic control group.

Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in 18 patients following DAAs therapy at 6.8 ± 1.3 months following treatment termination, mainly in patients with LS > 25 kPa (Table 2).

Sustained virological response (SVR) was achieved in 316 patients which was significantly higher in the control non-cirrhotic patients (127/130, 97.7%) when compared to the cirrhotic group with LS > 25 kPa (118/145, 81.4%) and group with LS 12.5–25 kPa (71/105, 67.6%) (p = 0.001).

The variables which correlated with the occurrence of complications were shown in Table 4.

Logistic regressive analysis revealed that unfavorable outcome and increased incidence of complications during DAAs were independently associated with severity of thrombocytopenia (p = 0.001), LS (p = 0.001), liver volume (p = 0.002), and gamma globulin levels (p = 0.004).

In the sorafenib group, unfavorable outcome and complications were independently associated with PDW/MPV magnitude (p = 0.001), level of ammonia (p = 0.001), LS (p = 0.001), and liver volume (p = 0.001).

ROC curve was applied to define the cutoff values of the predefined variables with the highest sensitivity, specificity and accuracy. In DAAs-treated group, liver stiffness > 20 kPa, thrombocytopenia < 78,000/μl, liver volume < 500 ml, gamma globulin > 4 gm/dl

PDW/MPV > 2.74, plasma ammonia > 87 μg/dl, LS > 25 kPa, liver volume < 490 ml were the most significant predictors of hepatic decompensation following treatment with sorafenib in HCC patients (Table 5, Fig. 3).

Discussion

Liver cell failure remains a life-threatening complication after exposure to therapeutic procedures, especially in advanced liver disease. It can be predicted via assessing residual hepatic cell reserve which would be achieved by sophisticated and expensive procedures such as computed tomography (CT) volumetric studies and gadolinium based MRI imaging [15, 16]

The liver reserve involves an efficient and sufficient number of hepatocytes and fixed tissue macrophages (Kupffer cells) capable of maintaining the synthesis of hepatic proteins, and elements of the innate immune system, excretion of toxic metabolites which are expected to be largely affected by liver volume [17, 18]

Non-invasive biochemical tests that are used to evaluate the severity of hepatic parenchymal fibrosis through direct biomarkers of hepatic matrix elements as hyaluronic acid, or assessing the synthetic function of the liver, and severity of portal hypertension as AST to platelet ratio index (APRI), fibro test, fibrosis-4 test (FIB-4), and enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) tests may show values that are not proportionate to the synthetic liver function [19, 20]

The current study aimed to assess easily applied variables which evaluate residual hepatic reserve to predict liability for complications and hepatic decompensation in cirrhotic patients with ablated HCC particularly when these patients were exposed to specific medical treatment such as DAAs and systemic therapy for HCC such as sorafenib. The results of the current study showed that patients with higher LS, PDW/MPV, gamma globulin, lower platelet count, and liver volume had significantly higher incidence of post-interventional complications (hepatic decompensation, HCC recurrence and HCV relapse after DAAs therapy); this can be explained by hepatocyte dysfunction associated with the severity of portal hypertension in this category of patients.

This goes in agreement with Lee et al who reported less HCC recurrence and better survival were associated with lower LS values. Also, Hegazy et al. reported more hepatic decompensation was seen with higher LS values after hepatic resection [21, 22].

Our results showed much more recurrence of HCC in DAAs therapy group mainly in patients with higher liver stiffness exceeding 25 kPa. This goes with many similar studies that reported increased prevalence of HCC recurrence after DAAs therapy [23, 24].

More hepatic decompensation and virological relapse were reported in our patients who received sorafenib and TACE, Park et al. and Lencioni et al. had reported much higher liver-related adverse events with sorafenib and TACE combination. However, Zhang et al reported better survival and good safety of Sorafenib& TACE in intermediate and advanced HCC [25, 26].

The current study had revealed that liver volume measurement by ultrasound with a cutoff value of (500 ml) reflects the more advanced liver disease associated with HCC. This is comparable to what was previously reported; liver volume at a cut-off value (495 ml) was predictive of complications after DAAs therapy mainly occurrence of HCC and reduced survival with sensitivity of 93.2%, specificity 72% [12].

Increased liver stiffness is associated with an increased risk of developing adverse events in liver cirrhosis and can be used as a valid non-invasive test for patient stratification. A study had enrolled 2052 patients who had developed hepatic complications or death during a median follow-up of 15.6 months; higher liver stiffness > 13.5 kPa was commonly associated with adverse events. The 2-year risk of death or complications were 19%, 34% in patients with liver stiffness 20–39.9, and ≥ 40 kPa, respectively [27, 28].

The platelet distribution width (PDW), reflects the variation in platelet size and was considered as a marker of platelet function and activation, higher value had been associated with increased cancer progression and metastasis and reduced overall survival [29]. A study had enrolled 241 patients with chronic HCV infection to assess the association between liver fibrosis, platelet counts, and platelet indices as MPV, PDW, and P-LCR and revealed that serum fibrosis markers as well as Fibroscan values were negatively correlated with PLT counts, but positively correlated with platelets indices [30], in the current study, a PDW/MPV > 2.74 was associated with more adverse outcome in patients with liver cirrhosis with HCC who were treated with sorafenib.

Ammonia is a byproduct of protein digestion by intestinal flora and is converted to glutamine in the liver before being converted to urea by renal metabolism. If ammonia bypasses the liver due to portosystemic collaterals or the inability of advanced liver cirrhosis to metabolize it, it causes hyperammonemia, which can pass through the blood-brain barrier, causing hepatic encephalopathy [31].

Previous researches had linked hyperammonemia to worsening Child-Pugh grade and the risk of hepatic encephalopathy [32, 33]. In the current study, plasma ammonia was significantly higher in patients with advanced cirrhosis and higher liver stiffness values > 25 kPa in patients treated with sorafenib or DAAs, and was associated with more complications and an unfavorable outcome at a cut-off value of 87 μg/dl mainly in cirrhotic patients with HCC who were treated with sorafenib.

These parameters should be applied to candidates for interventional hepatic procedures including surgical therapies for any other causes. A sufficient number of patients with liver cirrhosis were included in the study, so that clinical variables were carefully studied.

These non-invasive parameters included markers of portal hypertension, ammonia as a marker of liver metabolic capacity and liver stiffness by Fibroscan in addition to liver volume by bedside ultrasound, were efficient in appreciating residual hepatic reserve in liver cirrhosis with previously ablated HCC.

Conclusions

Prediction of hepatic complication and failure after DAAs in ablated HCC or after inoperable HCC who were managed with TACE followed by sorafenib can be appreciated by easily measured parameters as liver stiffness, severity of thrombocytopenia, liver volume, PDW/MPV, blood ammonia, and gamma globulins which could be used to postulate a non-invasive scoring system of residual hepatic reserve prior to non-surgical and surgical therapeutic interventions after HCC ablation for the best outcome of these patients and to avoid possible unwanted complications.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available on request.

Abbreviations

- APRI:

-

AST to platelet ratio index

- CTP:

-

Child-Turcotte-Pugh

- DAAs:

-

Direct-acting antiviral drugs

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- ELF:

-

Enhanced liver fibrosis

- FIB-4:

-

Fibrosis -4

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- LS:

-

Liver stiffness

- MELD:

-

Model for end stage liver disease

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PDW/MPV:

-

Platelet distribution width/mean platelet volume

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating curve

- SVR:

-

Sustained virological response

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for social sciences

- TACE:

-

Trans-arterial chemoembolization

References

Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J (2018) Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 391:1301–1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2

Lurje I, Czigany Z, Bednarsch J et al (2019) Treatment strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma-a multidisciplinary approach. Int J Mol Sci 20(6):1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20061465

Ahmad T, Yin P, Saffitz J, Pockros PJ, Lalezari J, Shiffman M et al (2015) Cardiac dysfunction associated with a nucleotide polymerase inhibitor for treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatology 62(2):409–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27488

Reig M, Marino Z, Perello C, Inarrairaegui M, Ribeiro A, Lens S et al (2016) Unexpected high rate of early tumor recurrence in patients with HCV-related HCC undergoing interferon-free therapy. J Hepatol 65(4):719–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.008

Poordad F, Nelson DR, Feld JJ, Fried MW, Wedemeyer H, Larsen L et al (2017) Safety of the 2D/3D direct-acting antiviral regimen in HCV-induced child-Pugh a cirrhosis - a pooled analysis. J Hepatol 67(4):700–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.011

Tu R, Xia LP, Yu AL, Wu L (2007) Assessment of hepatic functional reserve by cirrhosis grading and liver volume measurement using CT. World J Gastroenterol 13(29):3956–3961. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i29.3956

Slack A, Ladher N, Wendon J (2012) Acute hepatic failure. In: Wagener G (ed) Liver anesthesiology and critical care medicine. Springer, New York, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, London, pp 21–42. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.11-3-254

De Gasperi A, Mazza E, Prosperi M (2016) Indocyanine green kinetics to assess liver function: ready for a clinical dynamic assessment in major liver surgery? World J Hepatol 8(7):355–367. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v8.i7.355

Kwon AH, Matsui Y, Kaibori M, Ha-Kawa SK (2006) Preoperative regional maximal removal rate of technetium-99m-galactosyl human serum albumin (GSA-Rmax) is useful for judging the safety of hepatic resection. Surgery 140(3):379–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2006.02.011

Annet L, Materne R, Danse E, Jamart J, Horsmans Y, Van Beers BE (2003) Hepatic flow parameters measured with MR imaging and Doppler US: correlations with degree of cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Radiology 229(2):409–414. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2292021128

Childs JT, Esterman AJ, Phillips M, Thoirs KA, Turner RC (2014) Methods of determining the size of the adult liver using 2D ultrasound: a systematic review of articles reporting liver measurement techniques. J Diag Med Sonography 30(6):296–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756479314549070

Hanafy AS, Bassiony MA, Basha MAA (2019) Management of HCV-related decompensated cirrhosis with direct-acting antiviral agents: who should be treated? Hepatol Int 13:165–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-019-09933-8

Childs JT, Esterman AJ, Thoirs KA, Turner RC (2016) Ultrasound in the assessment of hepatomegaly: a simple technique to determine an enlarged liver using reliable and valid measurements. Sonography 3:47–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/sono.12051

Castera L, Forns X, Alberti A (2008) Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis using transient elastography. J Hepatol 48(5):835–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2008.02.008

Vauthey JN, Chaoui A, Do KA, Bilimoria MM, Fenstermacher MJ, Charnsangavej C et al (2000) Standardized measurement of the future liver remnant prior to extended liver resection: methodology and clinical associations. Surgery 127(5):512–519. https://doi.org/10.1067/msy.2000.105294

Tajima T, Takao H, Akai H, Kiryu S, Imamura H, Watanabe Y et al (2010) Relationship between liver function and liver signal intensity in hepatobiliary phase of gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethylene triaminepentaacetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr 34:362–366. https://doi.org/10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181cd3304

Medzhitov R, Janeway CJ (2000) Innate immunity. N Engl J Med 343(5):338–344. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917309.x

Alizai PH, Haelsig A, Bruners P, Ulmer F, Klink CD, Dejong CHC et al (2017) Impact of liver volume and liver function on post-hepatectomy liver failure after portal vein embolization- a multivariable cohort analysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 25:6–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2017.12.003

Petersen JR, Stevenson HL, Kasturi KS, Ashutosh NA, Parkes J, Cross R et al (2014) Evaluation of the APRI (AST, platelet ratio index) and ELFTM (enhanced liver fibrosis) tests to detect significant fibrosis due to chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol 48(4):370–376. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182a87e78

Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, Verkarre V, Nalpas A, Dhalluin-Venier V et al (2007) FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. Comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology 46(1):32–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21669

Lee J, Lee H, Kim S et al (2019) Follow-up liver stiffness measurements after liver resection influence oncologic outcomes of hepatitis-B-associated hepatocellular carcinoma with liver cirrhosis. Cancers (Basel) 11(3):425. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11030425

Hegazy O, Allam M, Sabry A et al (2019) Liver stiffness measurement by transient elastography can predict outcome after hepatic resection for hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Egypt J Surg 38(2):313–318. https://doi.org/10.4103/ejs.ejs_207_18

Reig M, Marino Z, Perello C, Inarrairaegui M, Ribeiro A et al (2016) Unexpected high rate of early tumour recurrence in patients with HCV-related HCC undergoing interferon-free therapy. J Hepatol 65:719–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.008

Conti F, Bionfiglioli F, Scuteri A, Crespi C, Bolondi L et al (2016) Early occurrence and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related cirrhosis treated with direct-acting antivirals. J Hepatol 65:727–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.015

Park J, Kim Y, Kim DY et al (2019) Sorafenib with or without concurrent transarterial chemoembolization in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: the phase III STAH trial. J Hepatol 70:684–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.11.029

Lencioni R, Llovet JM, Han G et al (2016) Sorafenib or placebo plus TACE with doxorubicin-eluting beads for intermediate stage HCC: the SPACE trial. J Hepatol 64(5):1090–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.012

Gomez-Moreno AZ, Pineda-Tenor D, Jimenez-Sousa MA, Sánchez-Ruano JJ, Artaza-Varasa T, Saura-Montalban J et al (2017) Liver stiffness measurement predicts liver-related events in patients with chronic hepatitis C: a retrospective study. PLoS One 12(9):e0184404. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184404

Pang JX, Zimmer S, Niu S, Crotty P, Tracey J, Pradhan F et al (2014) Liver stiffness by transient elastography predicts liver-related complications and mortality in patients with chronic liver disease. PLoS One 9(4):e95776. https://doi.org/10.1371/.journal.pone.0095776

Li N, Diao Z, Huang X et al (2017) Increased platelet distribution width predicts poor prognosis in melanoma patients. Sci Rep 7:2970PMID: 2859283. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03212-y

Shao LN, Zhang ST, Wang N, Yu WJ, Chen M, Xiao N et al (2020) Platelet indices significantly correlate with liver fibrosis in HCV-infected patients. PLoS One 15(1):e0227544. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227544

Iwasa M, Sugimoto R, Mifuji-Moroka R et al (2016) Factors contributing to the development of overt encephalopathy in liver cirrhosis patients. Metab Brain Dis 31(5):1151–1156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-016-9862-6

Wang Q, Wang Y, Yu Z, Li D, Jia B, Li J et al (2014) Ammonia-induced energy disorders interfere with bilirubin metabolism in hepatocytes. Arch Biochem Biophys 555-556:16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2014.05.019

Khan A, Ayub M, Khan WM (2016) Hyperammonemia is associated with increasing severity of both liver cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy. Int J Hepatol 2016:6741754. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6741754

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to university hospital clinical pathology and radiological departments.

Funding

No funding agent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: AS Hanafy. Data curation: AS Hanafy. Formal analysis: all authors. Methodology: AS Hanafy and H. Atia. Interventional radiology: SS. Writing—original draft: AS Hanafy. Writing—review and editing: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients signed informed consent. The study was carried out following the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Zagazig University—Faculty of Medicine Ethical Committee, reference number is not available.

Consent for publication

Patients had agreed use of their data in research and publication without the appearance of their names.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanafy, A.S., Mohamed, M.S., Taleb, M.A. et al. Predictors of residual hepatic reserve and hepatic decompensation in cirrhotic patients after ablated hepatocellular carcinoma treated by DDAs or systemic therapy. Egypt Liver Journal 11, 83 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-021-00151-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43066-021-00151-2